Abstract

Rental housing is increasingly becoming the key shelter option for the poor living in and moving into cities, including those living in informal settlements. The paper revisits the production of rental housing in informal settlements within the new contours of a neo-liberalism with stronger social agendas in Latin America drawing on the case of landlords in Brazilian favelas. The contributions of the paper are twofold: first, it explores the different elements impacting the development of rental housing in informal settlements in Brazil, from the socio-economic to the political, from the state to the intra-settlement dynamics; and second, it assesses how these conditions determine the way landlords operate and produce rental housing. The analyses add to our understanding of the contemporary forms of housing informality reproduction in emerging economies and how individuals pervade the circuits of market and survival constructing their livelihoods on the basis of the economic and social resources from renting.

1. Introduction

A wealth of studies suggest that rental housing is increasingly becoming the key shelter option for the poor living in and moving into cities (UN-Habitat Citation2003, Citation2011; Wragg Citation2010; IDB Citation2011; Kumar Citation2011; Peppercorn & Taffin Citation2013). Across the world, approximately 1.2 billion people live in rented accommodation, one-third of the population living in urban areas. In Latin America, it is estimated that between 20% and 40% of households rent (IDB Citation2011) and there is much evidence to suggest that landlords and tenants account for a significant share of the poor living in informal settlements (UN-Habitat Citation2003, Citation2011). In Brazil, 10.2 million households were renting in 2010, accounting for 20.9% of the total urban housing stock. From the total rented households, between 20% and 25% were estimated to be poor, living on three minimum wages or lessFootnote1 (IBGE Citation2010; Pasternak & D’Ottaviano Citation2012).

Academics (Edwards Citation1990; Gilbert Citation1993; Kumar Citation1994, Citation1996a, Citation1996c, Citation2011; Wragg Citation2010) as well as international development agencies (UNCHS Citation1993; UNCHS and ILO Citation1995; UN-Habitat Citation2003, Citation2011) are enthusiastic about the potential of the informal rental sector to provide shelter for the urban poor. Among the various comparative advantages, rental housing is seen as important for economic development and for creating livelihood opportunities – e.g. as a source of income generation and security for landlords – and for offering affordability, residential choice and mobility for tenants, especially transitional workers and vulnerable households. Yet, rental housing remains a much neglected topic in policy agendas (Kumar Citation1996a, Citation2011). Few governments outside Europe have formulated policies to help to develop rental housing and there is a general neglect to the conditions of tenants and landlords overall, and especially those living in informal settlements.

A lot of what is known about informal rental housing production and consumption in Latin America draws from research conducted during the 1980s and 1990s. The findings essentially describe low-income households reacting to austerity and structural adjustment, with increasing incidence of poverty and declining living standards. The critical recession period that most of the countries experienced in the 1980s substantially undermined the provision of welfare and housing. The introduction of a policy framework in line with liberalisation and less state intervention resulted in fewer or no social housing opportunities for the poorer (Maricato Citation1996, Citation2001). Dropping incomes, rising costs of living including household essentials and building materials hampered the capacity of self-helpers to provide for themselves (Gilbert Citation1993). The two main consequences of structural adjustment in most Latin American cities were the rapid increase in land invasion in cities and countries where it did not yet exist, and the development of informal housing markets in countries with control over informal land occupation. As pointed by Abramo (Citation2009), ‘the solution for those families without financial resources to purchase was choosing one of the following strategies: either occupy land or rent a shelter in an informal settlement’ (Abramo Citation2009, p. 38).

The turn of the millennium inaugurated a decade of political changes and socio-economic achievements for many countries in the region. In Brazil, reforms in the financial sector increased access to credit, enabled more investments in infrastructure and stimulated the domestic market, empowering households to consume. Measures to increase the minimum wage and strengthen social protection have contributed to reduce poverty and improve living standards. And yet, informal settlements, or favelas as they are popularly known in Brazil, have not shown signs of decrease. In fact, they continued to grow at a pace faster than cities. As favela dwellers gain a share in the consumer market, there is also increasing evidence that their dynamics of housing production and consumption become more entrepreneurial albeit still intertwined with livelihood strategies.

How have the recent socio-economic changes determined new regimes of housing production and consumption by the poor in informal areas? What has been the impact on informal housing markets and tenure landscapes? The paper engages with these questions drawing on an analysis of informal rental markets and landlords operating in the conurbation of Florianopolis, in the south of Brazil. The contributions of the paper are twofold:Footnote2 first, it explores the different conditions underlying the development of rental housing in Brazil, from the macro to the community levels; and second, it assesses how these conditions are reflected at the level of the household and impact rental housing production. The analyses add to our understanding of the contemporary forms of housing informality reproduction in emerging economies and how individuals pervade the circuits of market and survival constructing their livelihoods on the basis of the economic and social resources from renting.

The subsequent sections look at (a) the scope and methodology of the study (b) what is known about the production of informal rental housing; (c) the set of institutional, socio-economic and intra-settlement conditions contributing to the emergence of rental housing in Brazilian favelas; and (d) the conditions enabling production at the household level. The conclusion draws attention to how these conditions enlighten our understanding of informal rental markets in the context of the socio-economic and developmental changes occurring in Brazil in the 2000s.

1.1. Scope and methodology of the study

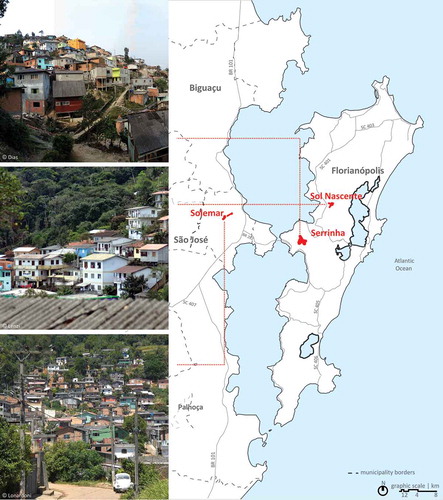

Findings of this paper were achieved primarily through case study research involving in-depth interviews with 73 landlords in three informal settlements in the conurbation of Florianopolis – Serrinha, Sol Nascente and Solemar – carried out between August and December 2010.Footnote3 The interview schedule included questions on the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of household members; working conditions and everyday mobility; the characteristics of the housing stock; housing trajectory, landlordism and the future housing aspirations; tenant–landlord relations and social engagement at community. Data from the 2010 National Demographic Census (IBGE Citation2010) and the CAD-Unico databaseFootnote4 supported quantitative analyses at the national and city levels on the socio-economic characteristics of households and the rental housing stock. The information collected from the case studies and descriptive statistics was complemented by desktop research and interviews with key stakeholders. The latter supported the analysis on the development of rental housing in Brazil. The study areas were selected according to their different location in the urban fabric, accessibility to livelihood opportunities, level of housing consolidation and state intervention ().

1.1.1. Serrinha

Serrinha is located in a strategic site in the heart of Florianopolis, well connected to employment opportunities and public facilities. The first residents arrived in the late 1970s, and the occupation intensified from the 1990s onwards. After a series of land conflicts threatens of eviction during the 1980s, the municipality authorised the families to remain in the area and started the installation of basic services in the early 1990s. The most intensive occupation was observed during the 1990s and the 2000s, following the first improvement in the service provision, although the land tenure has remained informal. The estimated number of households in 2010 was 853,Footnote5 and the average per capita income according to the national demographic census was 1.7 minimum wages (IBGE Citation2010). Since 2008, the area has been the object of upgrading interventions within the framework of National Growth Acceleration Programme – PAC-Slum Upgrading (PAC-Urbanização de Favelas) and received substantial investments in infrastructure and services.

1.1.2. Sol Nascente

Sol Nascente sits in a hilly area along a development corridor connecting the centre to the northern high-income tourist coastline of Santa Catarina Island. The occupation began in the mid-1980s, with the first settlers being attracted by the lower prices of and in an area with good location in relation to the city centre. The surrounding neighbourhood has become one of the main vectors of urban growth in Florianopolis, receiving a large amount of private and public investments and intensive development of high-income commerce and retail. This has been contributing to intensify the informal occupation and boost informal rental market, which has emerged most clearly during the 2000s (INFOSOLO-UFSC Citation2006). State intervention has been scant, but there is high level of community organisation and community-managed water system. In 2010, about 2000 people (820 households) lived in the area (AMSOL Citation2011) of which 30% were renting (IBGE Citation2010). The average per capita income was 1.5 minimum wages, less than half the average income in Florianopolis of 3.1 minimum wages.

1.1.3. Solemar

Solemar is located in the peri-urban area of Florianopolis fairly distant from the urban centre with limited access to the public transport system. The occupation developed in two main phases, the first in the 1970s with households settling on the base of the slope along the existing road system; and the second in the 1990s, advancing over the slopes in an environmentally protected zone with difficult accessibility. The population in 2010 was estimated at 2188, distributed in 600 households (IBGE Citation2010). The area is among the most poor in the conurbation of Florianopolis with income per capita averaging 0.88 minimum wages (449.5 BRL – 242.9 USD) in 2010 (IBGE Citation2010). Comparative data from the 2000 and the 2010 censuses evidenced that poverty levels increased in Solemar. In 2000, 76% of the head of households received up to three minimum wages, whereas in 2010, the share increased to 81.1%. Social organisation was weak, and the state has intervened to try to prevent settlement consolidation.

2. Rental housing, informal property markets and livelihood

Housing studies have greatly contributed to our understanding of urban poverty and livelihood. The work of Turner (Citation1968, Citation1976, Citation1978) unravelled the ways in which poor people mobilised resources and self-organised to construct their houses in the peripheries of Latin American cities. His main opponents (Bromley Citation1978; Burgess Citation1978; Pradilla Citation1987; PREACL Citation1987, Citation1990; Portes Citation1989) criticised the overemphasis on the agency of the poor waging a debate on the use and market value of housing which became the bedrock of international development and poverty alleviation approaches in the decades to follow (World Bank Citation1993; De Soto Citation2000).

Rental housing studies from the 1980s and the 1990s have added to this debate. A wealth of studies drawing on readings of political economy and new-Marxism (Gilbert Citation1981, Citation1983, Citation1987, Citation1993; Kumar Citation1994, Citation1996b, Citation1996c) showed how on the ground dynamics of housing production and use were conditioned by structural constraints, austerity at the same time as they were central to individuals’ and families’ struggles against poverty. Kumar’s (1996b) taxonomy of landlordism drawing on the concept of ‘petty commodity’ was particularly valuable to elucidate the dialectical interaction of use values and exchange values in the act of renting.

More recently, in the 1990s and the 2000s, scholarship shifted the focus from Latin America to other parts of the globe, bringing new empirical evidence about landlords and the low-income rental sector in several parts of Africa (Muzvidziwa Citation2003; Precht Citation2005; Cadsted Citation2006; Huchzermeyer Citation2007; Gulyani & Talukdar Citation2008), transition economies in Europe (Dubel et al. Citation2006) and Asia (Huang Citation2003, Citation2013; Fitzgerald Citation2007; Kumar Citation2009). These studies have further revealed the variety of informal rental submarkets existing, the different realities of landlords across the globe and the myriad of resources and strategies they draw on, operating at different scales from more survivalist to more entrepreneurial.

The livelihood scholarship starting in the late 1990s brought the analysis a level down to the household level, looking at how land and housing integrate the portfolio of assets available for the urban poor (Rakodi Citation1995, Citation1999; Moser Citation1998, Citation2007; Mooya & Cloete Citation2007, Citation2010; Satterthwaide Citation2008; Marx Citation2009; Mooya Citation2011) and how individuals mobilise such assets against hardship (Amis Citation2002; Payne Citation2002). As noted by Rakodi, out of the portfolio of resources that the urban poor have at their disposal, land and housing ‘provide increased security, a location for home-based enterprise, and a potential source of income from rent’ (Rakodi Citation1999, p. 325). The work of Wragg (Citation2010) on the landlords in Lusaka marks a shift from political economy to people-centred analysis in rental studies, using a livelihood systems approach to understand the different assets and strategies landlords draw on in order to produce accommodation for rent.

This paper adds to the scope of empirical evidence on informal rental housing and landlords in the Latin America region. First, it provides new evidence on informal rental housing in Brazil, the largest and most populated country in the continent. Second, it revisits housing informality within the new contours of neo-liberalism in Latin America. This is a new structural context in which many countries are setting broader development objectives and providing for stronger social agendas (Pastor & Wise Citation1999; Ffrench-Davis Citation2000) as well as being proactive in tackling issues from market failure to poverty alleviation. The intention is not to create a new conceptualisation of landlordism but rather to supplement the structural analyses dominant in rental studies in the 1980s and the 1990s with a dialectical understanding of the relationship between structural constraints and the practices of social actors in this new structural context. In doing so, the different sections seek to understand the conditions created by the state and economy, as well as also those which accrue from neighbourhood, community and household realms.

3. Institutional, socio-economic and spatial conditions contributing to the emergence of rental housing in Brazilian favelas

Brazil, as most of Latin America, is a country of homeowners with more than 70% of the housing stock owner-occupied (IBGE Citation2010). However, the tenure landscape in the country has experienced some changes in the last decade. Between 2000 and 2010, for the first time since the 1940s, ownership rates in urban areas decreased – from 74.7% to 72.6% – and tenant households increased – from 16.8% to 20.9% (IBGE Citation2010). In real numbers, this has meant an increase of 64% in the stock of rented houses in urban areas in the period, a rise from 6.3 million to 10.2 million. The growth of the rented stock was double the one observed for the overall housing stock in the country which increased by 32%, from 37.3 million in 2010 to 49.2 million in 2010 (IBGE Citation2000, Citation2010).

Renting constitutes an alternative for an increasing number of low-income people, including those living in informal areas. Out of the total 10.2 million households renting accommodation in 2010, between 20% and 25% were poor earning up to three minimum wages a month (IBGE Citation2010; Pasternak & D’Ottaviano Citation2012). In cities like São Paulo, Rio Janeiro, Recife and Florianopolis, renting is increasingly becoming the first step means into housing markets in informal settlements where it can account for 40–50% of all informal housing market transactions (Leitão Citation2004, Citation2007; Baltrusis Citation2005; Abramo Citation2009; Abramo & Pulicy Citation2009; Lacerda & Melo Citation2009; Sugai Citation2009).

Florianopolis is one of the capital cities in Brazil with the highest proportion of rental housing, at 25.9% (IBGE Citation2010). A strong tourism sector and a high concentration of university students are some of the factors swelling the sector. As the capital, Florianopolis has a vital role in the economy and concentrates the bulk of employment opportunities, services and public facilities. A fast growing economy has attracted a high inflow of low-income migrants – especially in sectors like construction and services – increasing the demand for affordable housing. However, formal markets only cater for the middle class and high-income groups, and a structural inability of local governments to address the housing needs of the most poor endures. With few or no options, the majority of low-income households in Florianopolis as well as in the neighbouring cities address their needs informally, increasingly through renting a room or a house in informal settlements. High increases of rental stock have been observed in informal settlements in the 2000s (INFOSOLO Citation2006; Lonardoni Citation2008, Citation2014). For instance, in the space of 4 years, 2006–2010, the rental stock in Serrinha has more than doubled (Lonardoni, Citation2008, Citation2014), and from the sample of landlords interviewed by this study in Serrinha, Sol Nascente and Solemar, 75% had been letting accommodation for less than 5 years, indicating the recent consolidation of this market.

3.1. Impact of changing macroeconomic conditions and the role of the state

There are many ways in which the emergence of rental housing in informal settlements in Florianopolis can be elucidated by the macroeconomic, social and institutional transformations taking place in Brazil in the 2000s. The turn of the millennium marked a series of achievements for the Brazilian economy. The country opted for a macroeconomic policy and structural reforms to stimulate the domestic market increasing investments in infrastructure and empowering households to consume. Economic reforms brought discipline to the government’s finances and stability allowed businesses to invest and increase public revenues. Of particular importance have been the measures to strengthen the social protection system, including the policy of increasing minimum wage above inflation rates, social and cash transfer programmes such as Bolsa Familia (IPEA Citation2011). The per capita expenditure in health, education, sanitation, welfare and housing doubled in the period 1995–2010, from 1380 BRL (746 USD) to 2830 (1530 USD). Income transfer programmes have focused on the most vulnerable and helped to reduce poverty.Footnote6 Access to credit and financial inclusion has also improved, providing for both low-income and informal sector workers (FEBRABAN Citation2011). In 2013, the Crediamigo Programme celebrated 15 years of existence with more than 3 million clients – 44% were beneficiaries from social programmes – and 10.8 billion USD disbursed.Footnote7 A combination of the expansion of the labour market, better access to credit and an increased minimum wage has contributed to a process of income class ascension and new patterns of consumption and investment. These have created opportunities for slum dwellers to invest in housing consolidation and rental housing production, on the one hand, and to meet the costs of rental accommodation, on the other hand.

Although the labour market has expanded, there has also been an accelerated increase of vulnerable and temporary employment and persistent high rates of informality (IPEA Citation2012). In 2010, 50% of the economic active population still remained informally employed (Etco and FGV Citation2011). In addition, the turnover rates in the labour market increased, with the construction sector being one of the most volatile (Corseuil & Ribeiro Citation2012). Compared to 25 other countries, Brazil had in 2009 the second shortest average period of job retention only behind the US (DIEESE, p. 8). Under such conditions, renting becomes instrumental in coping with job instability as it allows for more residential flexibility and enables workers to be ‘mobile’ to access employment opportunities.

Other aspects of rental housing emergence may be elucidated by demographic changes resulting in new patterns of population distribution, new modes of living, household arrangements and housing preferences. One of the specificities is given by the distribution of the population towards newly and mid-size urban agglomerations. The conurbation of Florianopolis, including the capital and its surrounding cities – São José, Palhoça and Biguaçu – are among the fastest growing in the country, with annual growth rates above 3.0%, three times that of metropolises such as São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro (IBGE Citation2010). The growing demand for land and housing in urban areas and the impact on informal property markets cannot be underestimated, especially when neither the government nor the formal market offer alternatives for the majority of low-income households. Strict zoning, property speculation propelled by the tourism and state control over new occupations have only further augmented the challenges to access housing in the conurbation of Florianopolis, where it is estimated that 20–25% of the population live in some 170 informal settlements (INFOSOLO-UFSC Citation2006; Miranda Citation2010; PMF-PMHIS Citation2012).

At the household level, the changes refer to the transforming role of women and the reduction of family size. The participation of women in the labour market has determined changes in the political economy of household delaying and/or reducing childbirths and increasing income levels. The average number of children per family, which was 6 in the 1980s, has fallen to below 2 in the 2000s. A number of studies have associated rental choice to demographic and life-cycle aspects of these kind, especially those which suggest a greater presence of young couples and smaller families (Gilbert & Ward Citation1985; Gilbert & Varley Citation1990; Gilbert Citation1991; UN-Habitat Citation2003).

The economic upturn in Brazil has also resulted in spin-offs in the public housing sector that may have contributed to changes in the housing dynamics in informal settlements. With fiscal balance on the surplus side and reserves growing, the government was able to increase investments, credit and subsidies for housing programmes (IPEA Citation2011). Between 1999 and 2009, public investments in housing increased from 0.17 to 0.77 of the GDP (IPEA Citation2011). In 2007, the government launched the National Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) with one of its streams, the PAC-Slum Upgrading (PAC-Urbanização de Favelas), channelling significant federal resources along with those prompted by states and municipalities to improve infrastructure, housing and accessibility in favelas. With PAC, the federal government allocates resources and subsidies for local governments to improve sanitation, housing conditions and accessibility in large-scale and complex favela settings (Ministério das Cidades Citation2010). Since 2007, the programme has expanded investments to several cities in the country. More than 700 upgrading projects were ongoing in 2010, involving a 24 billion BRL (13 billion USD) investment and reaching 1.8 million households (Ministério das Cidades Citation2010).Footnote8 In Florianopolis, PAC allocated 70.8 million BRL (38.2 million USD) to execute urbanisation projects in the Maciço Central, a conglomerate of 17 informal settlements and 5677 households located in the heart of the city (Ministério das Cidades Citation2010). Although progress has been slow in de facto tenure regularisation, PAC interventions have contributed to an increase in perceived tenure, stimulating housing consolidation and property markets, including rental markets.

At a spatial level, important dimensions of the vulnerability of low-income households remain related to segregated patterns of urban land occupation in Brazilian citiesFootnote9 and the lack of affordable housing in sites where people can have access to enhanced services and livelihood opportunities. Little has changed in this segregated pattern – in contrast to the progress made in other areas of social development – reinforcing the demand for housing and rental market consolidation in areas which become better serviced, with infrastructure and above all better accessibility. Public transportation is precarious and mobility costs high, only reinforcing the strategic importance of the informal settlements located in central areas where accessibility and living conditions are better. In the conurbation of Florianopolis, the study found that the incidence of low-income renting was concentrated in the capital, especially in the central district or close to the main roads, subcentres and in areas with better connectivity to the transport network.

The general sense emerging from the analyses indicates that in spite of Brazilians having accessed better wages, social protection and opportunities for consumption, the lack of affordable housing options out of the informal settlements persists. This is evidenced by the continuous growth of favelas during the 2000s. In 2010, 11.4 million people, 6% of the country population, lived in favelas – 5 million more than the population in 2000, which was 6.5 million (IBGE Citation2000, Citation2010). Not only have favelas continued to grow in the period, but they did so eight times faster than formal areas of cities. While conditions have improved for households to consolidate their houses, buying a house or a plot of land in informal settlements has become more difficult and many of which who have joined the favelas in the period have done so as tenants.

3.2. Intra-settlement and community-level dynamics

The intra-settlement analysis showed that rental housing development was a further step in the process of land occupation and housing consolidation, emerging in response to continuous and increasing demand for accommodation. Other important conditions for rental housing production were determined by the pace of urban development in surrounding areas, the levels of state intervention and control over informal land and housing occupation in the settlement, and intra-settlement social dynamics which emerged under particular circumstances to regulate informal market development.

Locational attributes and the urban development dynamics in surrounding areas had an impact on rental market development in the settlement analysed. In Serrinha, rental housing started in the mid-1990s, subsequent to a period of intensive population growth. Located at the core of a booming neighbourhood, the settlement has a privileged location in relation to employment opportunities and access to services attracting the housing demand and contributing to the rental growth. Serrinha is also situated adjacent to the largest university campus in the city and surrounded by a growing and dynamic formal rental market to supply the housing demand of students and workers. Many landlords interviewed in the settlement referred to this as being influential to the expansion of their rental housing stock: ‘People here see that everybody is constructing studios to rent out and they want to do the same’.

In Sol Nascente, informal property markets and particularly rental housing production started in the early 2000s propelled by a sudden demand for housing of construction workers as a large scale real estate development started to be built next to the settlement. Residents in Sol Nascente, many of which were also small entrepreneurs working in construction, started to build accommodation to rent for the new demand of construction workers. Initially, production was undertaken only by a few residents adding rooms and extending their own houses as possibility to complement household income and improve security. But it rapidly became a widespread practice among other residents with some reaching a larger scale and a more commercial activity. Social networks in the construction sector were the main mechanism by which housing seekers and landlords found out about opportunities to rent. Through these networks, housing owners accessed cheap labour and building materials, which, combined with better salaries, offered the favourable conditions to invest in rental housing production. Many landlords interviewed in Sol Nascente counted on labour provided by their own tenants to construct and maintain the stock in exchange for accommodation. Exchange relations and access to resources drawing on social capital and informal networks not only enabled landlords to expand their stock very fast, but also contributed to ‘disseminate’ the practice and the modus operandi of rental production within the settlement.

As regards the state, the influence over rental housing development was observed in two main ways: first, through investing in infrastructure and stimulating housing consolidation; second, by controlling the expansion of informal occupation and the commercial use of public land. Both in Serrinha and Sol Nascente piecemeal and yet gradual public infrastructure provision contributed to ratify the sense of tenure security, stimulating the consolidation of housing structures and the expansion of rental accommodation. In Serrinha, the two most intensive periods of occupation growth and housing consolidation happened subsequent to public infrastructure provision in the mid-1990s and most recently in 2007. The latter under the framework of the national slum upgrading programme PAC with its interventions focusing on the improvement of sewage, drainage and roads systems. Better infrastructure and accessibility have attracted new people, increased the demand for housing and propelled many to invest in the construction of accommodation for rent. State intervention in the framework of PAC also directly boosted rental markets through the distribution of a temporary rental subsidyFootnote10 for relocation of households living in hazardous areas or displaced by the infrastructure works. The subsidy contributed to increase the demand for rental housing in Serrinha as well as within the other informal settlements covered by the upgrading programme. In Serrinha, the rental housing stock more than doubled between 2006 and 2010 during the PAC interventions (Lonardoni Citation2007, Citation2014).

In Solemar, the process developed differently with state intervention working to hinder housing consolidation and market development. Informal land markets have been common since the initial phases of occupation in the 1970s, although the occurrence of rental only started in the 1990s. The sector experienced intense growth in the mid-2000s as a result of population inflow and demand for housing. In 2005, the control of local authorities over the expansion of informal occupation intensified, particularly in the fringes of the settlement. Government officials monitored the arrival of new families on a daily basis and controlled occupation by restricting access to water, including through cutting clandestine connections. Many households moved out and a decrease of population was observed in the late 2000s. Housing prices devaluated and the opportunity costs of owning increased. Rental housing practically disappeared, remaining an option only for newly arrived migrants in the more consolidated parts of the settlement.

Of particular significance is the way in which the terms of state control in Solemar are made very clear with regard to preventing the commercial use of public land. It was generally accepted that people could occupy land informally to provide for their shelter, but not to use land for commercial purposes, determining the ways in which residents perceived their right to embark on rental housing production. This is illustrated in the following attest:

It is clear to us that the government lets us live here without paying anything. The government stops the market; the officials come here and say it is forbidden! Of course, they cannot be here all the time, but if someone reports that someone else is renting out, they [officials] come straightaway, take your rent [the property] and give the house to the tenant. Because this land is public, conceded to us; no one can say one owns the land (…) A newly-arrived person may possibly rent, but then they soon realize they have no obligation to pay rent. The tenure belongs to who is on top of the land. As soon as they realise, tenants won’t pay the rent and will grab the property. And you complain to whom? (…) To give you an idea, one cannot leave the house empty or vacant. If you leave the house empty for a couple of months the officials come and demolish it. They’ve demolished a lot of empty shacks here. I’ve seen it a lot! (L01 SO)

The idea that this area is an invasion is still very strong. For example, here is very difficult for anyone to sell one’s houses on instalments, because everybody knows the land is squatted and people may not pay if they wish to do so. One only sells on instalments based on trust, to people one knows well. Otherwise, people are afraid of losing their properties. (L04 SO)

The resistance of public authorities to the commercial use of land in Solemar must be considered in light of the historical struggles over the right to housing that pitted favela dwellers and community-based organisations (CBOs) against the state in Brazil in the 1980s and 1990s. The new urban legal framework implemented by the 1988 Federal Constitution and then detailed by the 2001 City Statute Law sought to guarantee the ‘right to the city’ by promoting the social function and use value of land as opposed to the commercial approach to land and property (Fernandes Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Maricato Citation2010). A range of instruments to restrict housing market consolidation in informal settlements was envisaged with the intention of protecting favela dwellers from gentrification, but also with the aim of guaranteeing the social and legitimate use of public land.Footnote11 Although municipalities have interpreted and regulated differently these provisions – which may explain the different approaches adopted in Solemar, under the jurisdiction of the municipality of São José, and Serrinha and Sol Nascente, under the jurisdiction of Florianopolis – there has been very little oversight of state authorities over informal land and housing and markets development in informal settlements. The case of Solemar is an exception which stands to illustrate how state intervention has hindered rental housing market development.

In Serrinha and Sol Nascente, the CBOs were the ones opposing the development of housing markets. These entities have existed since the beginning of settlement occupation and been at the forefront of negotiations with government authorities over land disputes, tenure security and infrastructure provision. CBOs in Serrinha and Sol Nascente have also played an important role in strengthening the political awareness of residents, especially long-term residents, with regard to their rights to use land and forms of contestation before the state. The constitutional provisions on the social function of land not only opened precedent but have been important to bargain on housing and land rights. Over time, and especially with the population growth and increase in the demand for housing, CBOs have neither prevented nor regulated informal property markets. However, some of their actions have served to delay commodification of land and particularly the growth of rental housing production. This has occurred through the promotion of the use value of land and pronouncements against property concentration and other outcomes of rental growth that affected the collective interests of the community.Footnote12 The objections to rental markets were elucidated during interviews with community leaders:

The explosion of rental house here is concerning. According to the legislation it is not allowed to build accommodation to rent out here and yet people construct more and more. This land is public and landlords know that they are irregular, but they continue because local authorities never supervise. (Community leader in Serrinha)

For the community it [rental housing] brings nothing. It only attracts more people and is affecting our water resources. If this rampant construction continues, the capacity of our reserves will finish in the next five years (…) Landlords only care about their gains and the tenants don’t bother because they will move away soon. (Community leader in Sol Nascente)

The judgement of residents regarding the use of land and housing markets also differed in the cases analysed. Overall, long-term residents tended to be resistant towards the growth of rental housing. In Solemar, this position was generalised and most of the people adopted the state position and objected to the commercial use of public land to the detriment of poorer tenants. In contrast, residents in Serrinha and Sol Nascente had become more indifferent to the debate about the use value of land and housing. The second and third generation of favela dwellers as well as newly arrived migrants established relations to land and housing which were already commercial from the outset and more secured in terms of tenure.

However, increasing complaints from dwellers pointed to the ways in which rental housing growth was changing standards of conviviality and social trust at the community level. By enabling the rapid inflow of population and engendering new patterns of residential mobility with higher turnover and short residence in a premise, rental housing was commonly associated to negative externalities such as an increase in crime, weakened neighbourhood ties and less social trust. These are illustrated by the following comments:

Before we used to know who lived here, nowadays it changes all the time… we never know who our neighbor is. There are always strange people around. (Resident of Sol Nascente)

I miss the time I used to know my neighbor. Nowadays someone else moves in each and other month. The community is a mess. I cannot leave my windows open, I don’t let my daughter play outside anymore…. (Resident of Serrinha)

Intra-settlement dynamics did not prevent market development but defined the social contours for rental housing production. State control and the role of CBOs appeared as being important in circumscribing the behaviour of community dwellers towards commodification of land and house. Owner occupiers engaged in rental production negotiating spaces of return with neighbours and trying to minimise the negative externalities. This usually resulted in them adopting a protective approach towards non-recognised tenants, that is, making sure to choose the ‘good tenant’ and keep as far as possible a neighbourly environment. ‘I am renting, but I choose well my tenants. They are not causing any trouble’. While this was fundamental to enhance intra-settlement acceptance towards landlordism, it also defined more socially related contours of rental activity against the development of an exclusively profit-seeking market.

4. Households dynamics influencing the production of rental housingFootnote13

Landlords in Serrinha, Sol Nascente and Solemar took up rental housing production for a number of reasons such as to supplement income, enhance welfare and social security for themselves and their children. At the household level, circumstances influencing rental housing production included the positive economic outlook as well as age, family composition and life cycles. Being a long established migrant correlated positively with socio-economic stability, established networks, access to land and enhanced conditions to invest in room renting.

Landlords were on average 15 years older than tenants and had larger family structures, with higher proportions of married couples with children (). Only 8 out of 73 households interviewed were headed by one person only. Housing stability appeared as an important factor enabling investment in rental housing production. Landlords were mostly long-established migrants with average 18 years living in the conurbation of Florianopolis, at least twice the time of residence of migrant tenants. Their superior residential stability was also measured by the average time of 7.8 years living in the house at the moment of the interview, whereas tenants had been living in their premises for average 1.2 years. Landlords owned the house they lived in and could afford better quality housing, with considerably more availability of space. The size of housing units occupied by landlord households was almost double that of tenant households, a difference also reflected in the levels of household density and overcrowding ().

Table 1. Socio-economic profile of landlords and tenants.

Landlords had a general low level of education (measured in number of schooled years). In Solemar, only 25.5% of landlords had completed fundamental school, while the percentage among tenants was 37.5%. The majority worked in the construction sector or related activities with only a few having access to formal jobs – the rates varying from 34% in Sol Nascente to 50% in Solemar. In spite of fewer years of education and informal work, landlords were relatively well off. In fact, they earned substantially higher incomes than tenants and the average household in the settlement ().

In terms of resources, land was one of the most important in enabling rental housing production. Most of the landlords interviewed were long-term migrants who could either occupy or purchase a plot of land at affordable prices in the origins of settlement development. The increase of the rented stock in recent years has taken place incrementally extending structures horizontally on the plot or vertically through the addition of new floors. The lack of regulations and control has enabled landlords to construct with flexibility and save on building authorisations. While the majority built accommodation or extended their own properties, one-third of landlords declared to have purchased ready-made housing structures to rent out using savings or resources from another property sale.

The construction and densification processes required better technique skills and building materials which landlords accessed more easily as workers in the construction sector, drawing on social networks, but some also via formal market. Building materials were manufactured and industrially produced. The favourable economic background boosted salaries and increased purchase power. Another important element was the improved access to credit from finance institutions for low-income earners and informal workers. Approximately 30% of the landlords counted on micro loans or purchased building materials on credit to undertake construction. This is a rather different condition from earlier years when informal construction processes drew essentially on savings and self-labour. The main products and credit lines were available through the nationally owned bank CAIXA, including commercial loans with subsidised interest rates and special microcredit schemes to purchase building materials involving the bank and retailers (Construcard). Loans from family members and the income from rent were also used to produce accommodation.

The labour resources used in the construction included varying proportions of household, kinship and waged labour. Two-thirds of respondents worked in rental housing production themselves and 70% used paid labour along with their own, in spite of growing costs of labour. To minimise these costs, landlords counted on a combination of social capital found in networks in the construction sector and intra-settlement. They contracted people residing in the same settlement or facilitated the coming of people from rural areas to work in construction, offering accommodation to rent at arrival. Tenants also made up for an important source of labour for landlords selling their services in exchange for accommodation.

A complementary survey undertaken with tenants revealed the majority of landlords (about 75%) lived in the settlement and accommodated at least one of their tenants in the same plot. Most of them operated on a small scale, with the majority accommodating two or three tenant households (). Renting out impacted positively on the livelihoods of landlord households, but was not essential for their survival. Three-quarters of landlords received less than 30% of their household income from renting out accommodation (), which was actually a decent amount of money considering their total income and especially given the low investments made in the properties. Only one-fifth of them received more than 50% of the household income from rent. Landlords considered rent as a profitable activity, although very few had clarity on the amount they had invested over the years. The returns from renting were spent on household expenses, consumer durables and automobiles. One-third of respondents reinvested the income from renting on expansion of the stock and property accumulation and 50% had already purchased a second property. The overall favourable balance of renting was measured by 65% of landlords saying they intended to continue investing and expanding their rented stock.

Table 2. The scale of landlordism.

5. Conclusion

The analysis revealed many facets of the rental housing production which were associated with the course of Brazil’s economic and social transformations in the 2000s. The period was marked by important steps towards socio-economic development and improved labour market opportunities. Low-income people have accessed more opportunities of income and credit, including those working in the informal sector. The spin-offs over housing were measured in terms of a greater capacity of landlords to extend their houses and of tenants to meet rental costs. High turnover in the labour market, more mobile workers and changing household dynamics, with more working women and smaller households, have also added to the demand for rental accommodation.

Housing consolidation and the growth of informal property markets including rent were the main trends observed in informal settlements in the conurbation of Florianopolis in the 2000s. However, the analyses showed that important dimensions of the vulnerability of the poor remained. These related to the segregating patterns of urban development and the lack of affordable housing in strategic locations from the point of view of livelihoods. Informal landlords and informal rental markets were filling this gap and enabling access to these strategic locations. Strengthened investments in slum upgrading in some areas contributed to improve living conditions and strengthened the sense of tenure security, but also contributed to an increase in housing demand and informal housing markets. The intra-settlement analysis in Serrinha, Solemar and Sol Nascente showed that rental housing development was a further step in the process of land occupation and housing consolidation, responding to the increasing number of people seeking accommodation.

While the decision of landlords to invest in room renting appeared to be largely opportunistic, responding to an increasing demand, the positive economic outlook and improved security of tenure all played a role in their ability to respond to this demand. With better wages and more opportunities for credit, landlords could access resources that were critical to build and expand their housing stock. Having landed property and being a long-established migrant correlated positively with socio-economic stability and enhanced conditions to invest in rental housing. Capital found in social networks was an advantage to access other resources for rental housing production, such as labour and building materials. The lack of building regulations and the flexibility regarding contracts and maintenance helped landlords to respond quickly to opportunities when they appeared.

The state and CBOs were important in circumscribing the behaviour of community dwellers towards commodification of land and the development of rental markets. In Solemar, the terms of state control were made very clear with regard to using public land only for self-help housing purposes, preventing people letting their own houses or constructing houses to rent. In Serrinha and Sol Nascente, CBOs have pronounced against property concentration and other outcomes of rental growth that negatively affected the collective interests of the community, through overcrowding, increased pressure on services and problems of neighbourhood conviviality. While this has not prevented rental markets growth, it has influenced the opinion of other residents and defined the social contours for rental housing production. Landlords usually negotiated with neighbours and tried to minimise negative externalities of renting. This was fundamental to enhance community acceptance of landlordism. It also defined more socially related contours of rental activity against the development of an exclusively profit-seeking market. This analysis reveals the interplays between top-down structures and community politics in enabling and regulating housing production and consumption.

While most conditions were cyclical, there were also elements of transformation engendering and being engendered by the consolidation of informal property markets in favelas. These referred mainly to the nature of and the perceived right to use land and housing. Informal rental markets created opportunities and redefined contemporary forms of housing production and consumption so that informal dwellers gained a share in the consumer market and accessed opportunities to improve income. But rental housing emergence also appeared to reinforce a new polarisation with dwellers becoming more sensitive to the status of their houses as exchange goods and creating a new class of commercially minded landlords who are taking over the role of both the state and the private sector as the suppliers of affordable housing. The question that follows is how these transformations will affect access to housing in the long run.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fernanda Lonardoni

Fernanda Lonardoni is an architect by training with a background featuring research and practice on subjects related to urban informality and international development. Her PhD thesis explored the opportunities and constraints of rental housing markets for the urban poor in Brazil. As a housing practitioner, she has worked for UN-Habitat, the International Labour Organization and the World Bank.

Jean Claude Bolay

Jean Claude Bolay is a sociologist by training and has a PhD in Political Sciences and is a specialist in urban issues in Latin America, Asia and West Africa. He is leading since 2005 the Cooperation & Development Center at EPFL and Adjunct Professor in 2005, integrating the Laboratory of Urban Sociology of the Natural, Architectural and Buit Environment School.

Notes

1. The minimum wage in 2010 was 510 BRL (275 USD).

2. Findings of this paper originally result from a doctoral research conducted by the author between 2009 and 2012 on the residential mobility and livelihood of tenant households in informal settlements in Brazil. The interviews with landlords primarily aimed at elucidating the dynamics of access to housing for tenants, but also contributed to revealing important aspects of the production of rental housing that should be further analysed.

3. The sample included 42 interviews in Serrinha, 23 Sol Nascente and 8 in Solemar. Respondents were selected randomly and identified through previous interviews and surveys conducted with tenants. The research is qualitative, but with significance and representativeness at the settlement level. The triangulation with data from the national and municipal censuses also support general conclusions on rental housing production and the characteristics of landlords in other informal settlements in the conurbation of Florianopolis.

4. CAD-Unico (Cadastro Único para Programas Sociais) is a national socio-economic registry of Brazilian low-income households. The information is collected by municipal administrations and managed at the national level by the Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger. CAD-Unico contains information on income, housing conditions, access to work, health and education and is available to federal, state and local governments to design public policies and select beneficiaries for social assistance. In 2010, the cadastre of Florianopolis comprised more than 15,000 low-income households registered since 2003 (PMHIS P08 Citation2012, p. 21).

5. Estimated by the author based on analysis of aerial photo triangulated with data from the 2010 national census and field work counting in November 2010.

6. Poverty and extreme poverty measured by income levels have decreased but still remain significant, keeping socio-economic inequalities as a hallmark of Brazilian urban society. In 2010, 16.3 million people still lived in conditions of extreme poverty, with per capita monthly income of less than 70 BRL (37.8 USD).

7. Portal do Brasil. Available at http://www.brasil.gov.br/economia-e-emprego/2013/11/crediamigo-completa-15-anos. Accessed on 12.03.2014.

8. The pro-poor housing strategy of the government also gained lever with the launch of the ‘My House, My Life’ (MCMV) programme in 2009, complementing slum-upgrading initiatives with the provision of new affordable housing. In addition, the public-led housing provision through the MCMV programme, despite scaled-up investments and a preventive approach, has been criticised for reproducing strategies poorly tied to livelihood perspectives, namely by settling families in peripheral areas with poor accessibility to services and employment opportunities (UN-Habitat Citation2013). To some extent, the socio-spatial impacts attached to this programme have been pointed as a step back of the Brazilian urban agenda (Cardoso Citation2013).

9. Like in other metropolitan areas in Brazil, the conurbation process between the capital and the surrounding cities contributed to unify the urban fabric and strengthen socio-economic integration, but also reinforced segregating patterns of land occupation, whereby the poor are pushed to live in the outskirts of urban growth, while jobs continue to concentrate in the capital. In 2010, average 40% economic active population in the municipalities of São José, Palhoça and Biguaçu commuted to work having Florianopolis as their main destination (IBGE Citation2010).

10. Usually called Bolsa Aluguel or Aluguel Social, this housing subsidy is granted by some municipalities to low-income families who live in risk areas or are affected by public works. The monthly benefit – ranging from USD 150 to USD 250 depending on the city – is given on a temporary basis and beneficiaries are prioritised by social housing programmes.

11. The Brazilian Statute of the City regulates the Article 183 of the Federal Constitution, which deals with acquisition of property by the occupant of an urban dwelling who uses it for housing himself or his family. ‘The Federal Constitution, in its Article 183, guarantees to the holder of an urban property of up to 250 square meters and who does not have another property or who has not yet been the beneficiary of the instrument, the acquisition of the said property. In this case the possessor must demonstrate that he has occupied the property for at least five years, unopposed, and that he uses the property for dwelling purposes’ (Barros et al. Citation2010, p. 102). The implications for rental markets are clear as it is implicit that owners (and landlords) cannot claim for rights over properties other than the ones used for their own ‘dwelling purposes’.

12. Sol Nascente has a water provision system managed by the community organisation Associação dos Moradores do Sol Nascente – AMSOL. A fixed fee of BRL 1700 was charged monthly per household (in 2010), regardless of the consumption. The population increase and residential turnover generated by the increase in rental accommodation affected the consumption levels and posed difficulties for the AMSOL to manage the system.

13. In addition to the in-depth interviews with landlords, the findings presented in this section were also drawn on a survey questionnaire undertaken with tenants containing representative information at the settlement level.

References

- Abramo P, editor. 2009. Favela e Mercado Informal: a nova porta de entrada dos pobres nas cidades brasileiras. Porto Alegre: Habitare/Finep.

- Abramo P, Pulicy A. 2009. Vende-se uma casa: o mercado imobiliário Informal nas favelas do Rio de Janeiro. In: Abramo P, editor. Favela e Mercado Informal: a nova porta de entrada dos pobres nas cidades brasileiras. Porto Alegre: Habitare/Finep; p. 112–138.

- Amis P. 2002. Municipal government, urban economic growth and poverty reduction – identifying the transmission mechanisms between growth and poverty. In: Rakodi C, Lloyd-Jones T, editors. Urban livelihoods: a people-centred approach to reducing poverty. London: Earthscan; p. 97–111.

- AMSOL. 2011. Household survey, 2010–2010. Florianopolis: Community Based Organization Sol Nascente (Associação dos Moradores do Sol Nascente – AMSOL). (Not published).

- Baltrusis N. 2005. Mercado imobiliário informal em favelas e o processo de estruturação da cidade: um estudo sobre a comercialização de imóveis em favelas na Região Metropolitana de São Paulo [dissertation]. São Paulo: Federal University of São Paulo – FAUUSP.

- Barros AMF, Carvalho C, Montandon D. 2010. Commentary on the city statute. In: Carvalho C, Rossbach A, editors. The city statute of Brazil: a commentary. São Paulo: Ministry of Cities; Cities Alliance; p. 91–118.

- Bromley R. 1978. Introduction – the urban informal sector: why is it worth discussing? World Dev. 6:1033–1039.

- Burgess R. 1978. Petty commodity housing or dweller control? A critique of John Turner’s views on housing policy. World Dev. 6:1105–1133.

- Cadsted J. 2006. Influence and invisibility: tenant in housing provision in Mwanza City, Tanzania. Stockholm: Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University.

- Cardoso A, editor. 2013. O Programa Minha Casa Minha Vida e seus efeitos territoriais. Rio de Janeiro: Letra Capital.

- Corseuil CH, Ribeiro EP. 2012. Rotatividade de trabalhadores e realocação de postos de trabalho no setor formal do Brasil: 1996–2010. Nota Técnica. IPEA, Mercado de Trabalho n.50 [cited 2012 Feb]. Available from: https://ipea.gov.br/agencia/images/stories/PDFs/mercadodetrabalho/bmt50_nt03_rotatividade.pdf

- De Soto H. 2000. The mystery of capital: why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. New York (NY): Basic Books.

- Dubel HJ, Brzeski WJ, Hamilton E. 2006. Rental choice and housing policy realignment in transition: post- privatization challenges in Europe and Central Asia region. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3884. Washington (DC): World Bank.

- Edwards M. 1990. Rental housing and the urban poor: Africa and Latin America compare. In: Amis P, Lloyd PC, editors. Housing Africa’s urban poor. Manchester: Manchester University Press; p. 253–272.

- ETCO & FGV. 2011. Economia Subterrânea cresce no mesmo ritmo do PIB. Study elaborated by the Brazilian Institute for Ethical Competition (Etco – Instituto Brasileiro de Ética Concorrencial) together with the Getúlio Vargas Foundation (FGV – Fundação Getúlio Vargas). Available from: http://www.etco.org.br/noticias/beconomia-subterranea-cresce-no-mesmo-ritmo-do-pib/

- FEBRARAN. 2011. Relatorio Anual 2011. São Paulo: Federacao Brasileira dos Bancos.

- Fernandes E. 2007a. Implementing the urban reform agenda in Brazil. Environ Urban. 19:177–189.

- Fernandes E. 2007b. Constructing the ‘Right to the City’ in Brazil. Soc Legal Stud. 16:201–219.

- Ffrench-Davis R. 2000. Reforming the reforms: macroeconomics, trade, finance. London: MacMillan.

- Fitzgerald D. 2007. Access to housing for renters and squatters in tsunami- affected Indonesia. Oxfam International.

- Gilbert A. 1993. In search of a home: rental and shared housing in Latin America. London: UCL Press.

- Gilbert AG. 1981. Pirates and invaders: land acquisition in urban Colombia and Venezuela. World Dev. 9:657–678.

- Gilbert AG. 1983. The tenants of self-help housing: choice and constraint in the housing markets of less developed countries. Dev Change. 14:449–477.

- Gilbert AG. 1987. Latin America’s urban poor: shanty dwellers or renters of rooms? Cities. 4:43–51.

- Gilbert AG. 1991. Renting and the transition to owner occupation in Latin American Cities. Habitat Int. 15:87–99.

- Gilbert AG, Ward PM. 1985. Housing the state and the poor: policy and practice in three Latin American Cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gilbert AG, Varley A. 1990. Renting a home in a third world city: choice or constraint? Int J Urban Regional Res. 14:89–108.

- Gulyani S, Talukdar D. 2008. Slum real estate: the low-quality high-price puzzle in Nairobi’s slum rental market and its implications for theory and practice. World Dev. 36:1916–1937.

- Huang Y. 2003. A room of one’s own: housing consumption and residential crowding in transitional urban China. Environ Plann A. 35:591–614.

- Huang Y. 2013. An invisible slum: the production of an underground city in Beijing. In R. Ronald, editor. At home in the housing market. RC43 conference book of proceedings, University of Amsterdam, Centre of Urban Studies.

- Huchzermeyer M. 2007. Tenement city: the emergence of multi-storey districts through large-scale private landlordism in Nairobi. Int J Urban Regional Res. 31:714–732.

- IBGE. 2000. National demographic census, IBGE. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e de Estatística, IBGE.

- IBGE. 2010. National demographic census. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e de Estatística, IBGE.

- IDB. 2011. Development of the Rental Housing Market in LatinAmerica and the Caribe [Discussion Paper]. Washington (DC): Inter-American Development Bank. IDB-DP-173.

- INFOSOLO-UFSC. 2006. Mercados Informais de Solo Urbano nas cidades brasileiras e acesso dos pobres ao solo. Final Report; Florianopolis: Habitare/Finep. Available from: http://habitare.infohab.org.br/DetalheProjeto.aspx#relINFOSOLO-UFSC

- IPEA. 2011. 15 Anos de Gasto Social Federal - Notas sobre o período de 1995 a 2009. Comunicado IPEA, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada n.98 [ cited 2011 Jul 8] Available from: http://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/comunicado/110708_comunicadoipea98.pdf

- IPEA. 2012. Considerações sobre o Pleno Emprego no Brasil. Comunicado. 135. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA.

- Kumar S. 1994. In recognition of landlordism in low-income settlements in third world cities: a critical review of the literature. DPU Working Paper. 65. London: Development Planning Unit, University College.

- Kumar S. 1996a. Landlordism in Third World urban low-income settlements: a case for further research. Urban Stud. 33:753–782.

- Kumar S. 1996b. Subsistence and petty capitalist landlords: a theoretical framework for the analysis of landlordism in Third World urban low income settlements. Int J Urban Regional Res. 20:317–329.

- Kumar S. 1996c. Subsistence and petty-capitalist landlords: an inquiry into the petty commodity production of rental housing in low-income settlements in Madras [ unpublished PhD thesis]. London: Development Planning Unit, University College London. 3, 90.

- Kumar S. 2009. Subsistence and petty capitalist landlords: a theoretical framework for the analysis of landlordism in Third World urban low income settlements. Int J Urban Regional Res. 20:317–329.

- Kumar S. 2011. The research-policy dialectic: a critical reflection on the virility of landlord-tenant research and the impotence of housing policy formulation in the urban Global South. City. 15:662–673.

- Lacerda N, Melo JM. 2009. Mercado imobiliário informal de habitação na Região Metropolitana do Recife. In: Abramo P, editor. Favela e Mercado Informal: a nova porta de entrada dos pobres nas cidades brasileiras. Porto Alegre: Habitare/Finep; p. 112–138.

- Leitão G. 2004. Dos barracos de madeira aos prédios de quitinetes: Uma análise do processo de produção da moradia na favela da Rocinha, ao longo de cinqüenta anos [dissertation]. Rio de Janeiro: Federal University of Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ.

- Leitão G. 2007. Transformações na estrutura socioespacial das favelas cariocas: a Rocinha como um exemplo. Cadernos Metrópole. 18:135–155.

- Lonardoni FM. 2007. Aluguel, Informalidade e pobreza: o acesso à moradia em Florianopolis [ Master Thesis]. Federal University of Santa Catarina – PGAU, Cidade. Florianopolis: UFSC.

- Lonardoni FM. 2008. Aluguel, Informalidade e pobreza: o acesso à moradia em Florianopolis [master thesis]. Florianopolis: Federal University of Santa Catarina - PGAU, Cidade.

- Lonardoni FM. 2014. Within the limits and opportunities of informal rental housing: tenants and livelihood in Brazilian favelas [ PhD thesis n. 6091]. Lausanne: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

- Maricato E. 1996. Metrópole na periferia do capitalismo: Ilegalidade, desigualdade e violência. Estudos Urbanos 10. São Paulo: Hucitec.

- Maricato E. 2001. Brasil, cidades: alternativas para a crise urbana. Petrópolis: Vozes.

- Maricato E. 2010. The statute of the peripheral city. In: Carvalho C, Rossbach A, editors. The city statute of Brazil: a commentary. São Paulo: Ministry of Cities, Cities Alliance; p. 5–22.

- Marx C. 2009. Conceptualizing the potential for informal land markets to reduce poverty. IDPR. 31:335–353.

- Ministério das Cidades. 2010. Urbanização de favelas: a experiência do PAC. Brasília: Ministry of Cities – SNH. Available from:http://www.conder.ba.gov.br/ckfinder/userfiles/files/PAC%20Urbanizacao%20de%20Favelas_Web.pdf

- Miranda R. 2010. O Crescimento das Favelas em Florianópolis (1987–2007) [ Master Thesis]. Florianópolis: SENAI/SC.

- Mooya MM. 2011. Making urban real estate markets work for the poor: theory, policy and practice. Cities. 28:238–244.

- Mooya MM, Cloete CE. 2007. Informal urban property markets and poverty alleviation: A conceptual framework. Urban Stud. 44:147–165.

- Mooya MM, Cloete CE. 2010. Property rights, real estate markets and poverty alleviation in Namibia’s urban low income settlements. Habitat Int. 34:436–445.

- Moser CON. 1998. The asset vulnerability framework: reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Dev. 26:1–19.

- Moser CON. 2007. Reducing global poverty: the case for asset accumulation. Washington (DC): Brookings Institution.

- Muzvidziwa VN. 2003. Housing and survival strategies of Basotho urban women tenants. In: Larson A, Mapetla M, Schytler A, editors. Gender and urban housing in Southern Africa: emerging issues. Rome: Institute of Southern African Studies; p. 149–168.

- Pasternak S, D’Ottaviano MCL. 2012. Research on houses for rent in Brazil. Final Report. Washington (DC): Inter-America Development Bank (IDB).

- Pastor M, Wise C. 1999. The politics of second-generation reform. J Democr. 10:34–48.

- Payne G. 2002. Tenure and shelter in urban livelihoods. In: Rakodi C, Lloyd-Jones T, editors. Urban livelihoods: a people-centred approach to reducing poverty. London: Earthscan; p. 151–164.

- Peppercorn IG, Taffin C. 2013. Rental housing: lessons from international experience and policies for emerging markets. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications.

- PMF-PMHIS. 2012. Plano Municipal de Habitação de Interesse Social. Prefeitura Municipal de Florianópolis. Vol. 08. Florianópolis: PMF.

- Portes A. 1989. Latin American urbanization during the years of crisis. Latin Am Rev. 25:7–44.

- Pradilla E. 1987. Capital, Estado y vivienda en América Latina. México: Fontamara.

- PREACL. 1987. El Sector informal hoy: El Imperativo de actuar. PREACL Document 314. Santiago: PREACL.

- PREACL. 1990. Urbanización y sector informal en America Latina, 1960-1980. Santiago: PREACL.

- Precht R. 2005. Informal settlement upgrading and low-income rental housing. Impact and untapped potentials of a community-based upgrading project in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Paper presented at the Third World Bank Urban Research Symposium on “Land development, urban policy and poverty alleviation”; April 2005; Brasilia, Brazil.

- Rakodi C. 1995. Poverty lines or household strategies?: A review of conceptual issues in the study of urban poverty. Habitat Int. 19:407–426.

- Rakodi C. 1999. A capital assets framework for analysing household livelihood strategies: implications for policy. Dev Policy Rev. 17:315–342.

- Satterthwaide D. 2008. Building homes: the role of federations of the urban poor. In: Moser C, Dani AA, editors. Assets, livelihoods, and social policy. New frontiers of social policy. Washington (DC): World Bank.

- Sugai MI. 2009. Há Favelas e pobreza na Ilha da Magia? In: Abramo P, editor. Favela e Mercado Informal: a nova porta de entrada dos pobres nas cidades brasileiras. Porto Alegre: Habitare/Finep; p. 162–199.

- Turner JFC. 1968. Housing priorities, settlement patterns and urban development in modernizing countries. J Am Inst Plann 34:54–63.

- Turner JFC. 1976. Housing by people. London: Marion Boyars.

- Turner JFC. 1978. Housing in three dimensions: terms of reference for the housing question redefined. World Dev. 6: 1135–1145.

- UNCHS. 1993. Support measures to promote low-income rental housing. Nairobi: UNCHS.

- UNCHS and ILO. 1995. Shelter provision and employment generation. Nairobi: United Nations Centre for Human Settlement and International Labour Office.

- UN-Habitat. 2003. Rental housing: an essential option for the urban poor in developing countries. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- UN-Habitat. 2011. A policy guide to rental housing in developing countries. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- UN-Habitat. 2013. Scaling-up affordable housing supply in Brazil: the ‘My House My Life’ programme. Housing Practices Series, Vol. 2. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- World Bank. 1993. World Bank, housing: enabling markets to work. Washington (DC): The World Bank.

- Wragg E. 2010. Meeting Africa’s urban housing needs: landlords and room renting in Lusaka [dissertation]. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University.