ABSTRACT

Theoretically informed by the relationships between growth poles and regional development, this article investigates two industries in Iloilo City, a secondary city in the Philippines: business processing outsourcing (BPO) and English as a second language (ESL). The empirical analysis is based on 46 interviews. First, the results of the empirical investigation demonstrate that Iloilo City should be considered a genuine growth pole with a substantial degree of enabling institutions. Yet, two qualifications need to be made. While information technology–business processing outsourcing (IT-BPO) is booming, the ESL industry is still small and is heavily reliant on Korean students. Second, while banking on offshore services enables the Philippines to encourage regional deconcentration, it remains to be seen whether future growth of the IT-BPO and ESL industries will result in attaining inter-regional balance and providing a decent alternative to overseas migration. The implications of the results relate to labour markets, endogenous regional development theories and international integration.

‘Philippine officials welcomed the birth on Sunday [27 July 2014] of their country’s 100 millionth citizen with a cake, hope and concerns about how their poor nation can help ensure a decent life for its swelling population’ (The Guardian Citation2014).

1. Introduction

One of the most pressing issues for many people in the Philippines is finding and keeping a job that culminates in an acceptable living standard and that minimises the risk of falling back into poverty. Despite rapid economic growth in the Philippines since the beginning of the twenty-first century, poverty, unemployment and underemployment have not significantly declined. The incidence of poor households below the national poverty line (a threshold of 18,935 Philippine Peso per capita in 2012) was 21% in 2006, 20.5% in 2009 and 19.7% in 2012. In absolute terms, the number of poor households increased from 3.8 million in 2006 to 4.2 million households in 2012 (NSCB Citation2013, p. 2–14). Consequently, millions of Philippine people continue to work overseas, and each year thousands of fresh college graduates register at government agencies to become an Overseas Filipina/Filipino Worker (OFW). The term ‘exodus capitalism’ appropriately describes the socioeconomic state of affairs (Kondo Citation2014, p. 185–186). Kondo (Citation2014) argues that domestic systems and institutions have developed to formalise the exodus tendency, ‘to the extent that exporting people has become a “national industry”, involving almost every part of society’. Whereas the Philippines is well known for its role as a supplier of labour (Tyner Citation2004), relatively little research has been conducted on the domestic economic geography of employment dynamics and entrepreneurship.

This article focuses on one of the major strengths of the Philippine economy: the offshore-services industry based on benefiting from English language skills and availability of a large young labour force eager to find employment. The Philippines initiated the promotional policy of ‘next wave cities’ in 2009, aimed at attracting more foreign direct investment and at bringing jobs to cities other than the two leading metropolitan areas of the national capital region (NCR) including Manila and Metro Cebu (Kleibert Citation2014). Theoretically informed by the relationships between growth poles and regional development, this article investigates two industries in Iloilo City, capital of the Western Visayas (Region VI): information technology–business processing outsourcing (IT-BPO) and English as a second language (ESL) – teaching English to foreigners, mostly South Korean youth. The empirical analysis is based on 46 semi-structured and open interviews conducted from July to August 2014 and March 2015. At present, these two industries combined provide more than 11,000 jobs (interview with the chairman of Iloilo’s BPO Association and with the owners of English language schools) for predominantly young women in Iloilo who just completed college, yet several important questions remain:

What is the nature of employment? Is it temporary or permanent? How are the working conditions and what are the career prospects?

Will these two industries continue to spearhead the economic development of Iloilo? Is Iloilo a genuine growth pole, able to provide jobs to the thousands of annual young college graduates and lead the development of the Western Visayas?

Can these two industries eventually provide an alternative to exodus capitalism for the Western Visayas? In 2014, 240,000 OFWs originate from the Western Visayas (Manila Bulletin Citation2014; this excludes undocumented migrants and persons who have migrated overseas permanently).

Besides these empirical and socioeconomic considerations, this paper also aims to provide theoretical implications on the concept of the growth pole, originally formulated by Perroux (Citation1955). Due to over-urbanisation, pollution, congestion and climate change threats in many Asian metropolitan areas, the growth pole is enjoying a revival in academic literature and policy documents (ADB Citation2012; Sheng Citation2012). The next section focuses on the revival of the growth-pole strategy in Pacific Asia. The backbone of this article consists of the empirical sections on research methodology, introduction to the research area and research findings. The article closes with a discussion of the findings and conclusions.

2. Regional development: the revival of growth poles

The interest in growth poles as a policy for regional development outside the core areas of East and Southeast Asia has enjoyed a revival in the last decade or so. The Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s painfully demonstrated that growth-oriented policies predominantly focused on the largest metropolitan areas were not sustainable from a socioeconomic and socio-spatial point of view. For example, one of the effects in Indonesia was that many jobless people from urban areas (temporarily) returned to their village (Firman Citation1999; Silvey Citation2001).

The first wave of Keynesian types of growth-pole strategies became very popular in the 1960s and 1970s. According to Parr (Citation1999), the concept of growth pole in geographical space received a normative aspect by the early 1960s: ‘Attention was given to the possibility of pursuing a growth-pole strategy, the cornerstone of which would be the activation of planned or induced growth poles’. Perroux defined growth poles as ‘centers (poles or foci) from which centrifugal forces emanate and to which centripetal forces are attracted. Each center being a center of attraction and repulsion has its proper field which is set in the field of all other centers’ (Mercado Citation2002, p. 11). Furthermore, Parr argued that growth-pole strategies were employed to achieve four different but interrelated objectives:

reviving depressed areas,

encouraging regional deconcentration,

modifying the national urban system and

attaining inter-regional balance.

For instance, France actively sought stimulate growth in secondary cities – the so-called balancing metropolises policy – in the 1960s to reduce the dominance of Paris (MacLennan Citation1965); yet due to a lack of success the French government gradually shifted its attention to creating high-tech clusters and innovation rather than modifying the national urban system as the highest priority. Arguable the most famous example is the high-tech park Sophia Antipolis nearby Nice (Longhi Citation1999; Ter Wal Citation2013). It should be noted, however, that French high-tech policy has not been an overall success. Hosper (Citation2005) claims that the public elite lacked commercial insights in the 1980s which led to the failure of the micro-electronics industry. Furthermore, the neoliberal wave in the global political economy of the 1980s and 1990s reduced the four objectives mentioned earlier to second-order (if not lower) priorities in regional development policies. European governments had to downsize welfare arrangements, African and Latin American governments were under pressure to pay off debts under the structural adjustment programmes and several Asian economies were in the process of transition from planned to market-based strategies. Growth prevailed over socioeconomic and spatial redistribution. The increasing imbalance between the dynamic coastal areas of China and the inland provinces led the Chinese to rethink growth policies, culminating in the well-known Great Western Development Strategy, adopted in 2000 and covering 11 provinces. Although promoting inland provinces is still going on, Fan et al. (Citation2011) point out that regional inequality in China has stabilised since the mid-2000s, partly as a result of this development strategy. The result indicates that the Chinese government has been able to trigger initial processes of reviving depressed areas, regional deconcentration as well as modifying the national urban system.

The most ambitious and challenging ideal, attaining inter-regional balance, obviously is long-term process, and it is questionable whether such a balance in China and other emerging economies in Asia can be reached. India appeared to partially include the growth-pole strategy as well during the 2007–2012 Eleventh Five Year Plan (Kannan Citation2007), yet the 2012–2017 Twelfth Five Year Plan does not mention it (Planning Commission Citation2013). In the USA and Europe, the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, and the subsequent financial and economic problems, led to a cautious revival of neo-Keynesian economic and regional economic policies. For instance, the government of the United Kingdom embarked on policies to stimulate northern cities in order to reduce the dependence on London and surroundings.

A more interventionist role for the government in national economic space can be justified by the following three points. First, regional inequality has led to deteriorating social cohesion. In much of Asia the political elite is well aware of the interests of the people living in lagging rural regions. Not addressing urgent issues in those regions will ultimately lead to more rural-to-urban migration. Second, over-urbanisation is resulting in diseconomies of scale and decreasing returns (Sheng Citation2012, pp. 25–30) such as traffic congestion, air pollution, flooding, typhoons and housing constraints. Third, it appears that Myrdal (Citation1957, p. 13) realised remarkably well that the economy does not, by itself, tend to move to equilibria and convergence of regional endogenous capacities. Rather, he emphasised the persistence of backwash effects and spread effects. Backwash effects pertain to all the assets that peripheral regions lose to the core regions within the process of circular cumulative causation while spread effects are the possible ‘centrifugal’ forces from core to semi-core or semi-peripheral regions (Binns Citation2014, p. 102).

In light of the financial and economic problems in Europe at the end of the 2000s, Hadjimichalis and Hudson (Citation2014) contend that there is an urgent need to re-appreciate the work and recommendations of Keynes and Myrdal. The Asian Development Bank has started to worry about growing inequality and devoted its 2012 Asian Development Outlook to this topic. The bank shows that a substantial part of inequality has a spatial character and supports interventions in order to assist lagging regions such as improving regional connectivity, developing new growth poles, strengthening fiscal transfers and removing barriers to migration to more prosperous areas (ADB Citation2012, p. 82). An aggressive strategy, promoting too many growth poles and focusing on all lagging regions, is likely to fail, but given the increasing diseconomies of scale, environmental pressures and sometimes social unrest in huge metropolises such as Jakarta, Surabaya, Manila, Cebu, Bangkok and Ho Chi Minh City, it is imperative that people and firms have other options. In this light promoting certain growth poles makes sense, not to achieve full inter-regional balance but to reduce overconcentration, congestion, pollution and prevent social unrest. It will also provide opportunities for disadvantaged groups in society to migrate to their city of destination. As the World Bank (Citation2009, p. 80), usually not in favour of heterodox regional economic policies, admits:

The ethnic, linguistic, and religious barriers that may keep households from taking advantage of many opportunities to arbitrage geographic differences for employment and earnings can be the same barriers that cage poor people in lagging areas, perpetuate their poverty, and sharpen spatial disparities.

In sum, relocating to the most prosperous areas is not always possible and growth poles could then function as suitable alternatives. The case of Chongqing in China demonstrates (Cai et al. Citation2012; Liu et al. Citation2016) growth poles are likelier to be successful as drivers of regional development if there is an explicit focus on rural–urban integrating as part of the growth strategy. This might be possible in the case of agribusiness, manufacturing involving supplies from the countryside and tourism, but could be much harder if municipal authorities seek advanced services as the main driver of economic growth. Nevertheless, in the context of Southeast Asia’s populous areas activating growth poles should be given serious consideration based on a careful analysis of both supply and demand factors of the growth industries involved. The next section zooms in on the Philippines.

3. The growth pole in the Philippines

According to Mercado (Citation2002), regional development thinking and policies started to become an important and active part of national economic planning in the early 1970s. The National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) was established in 1972. Sub-national responsibility was created through the NEDA regional headquarters (Mercado Citation2002, p. 38). Thirteen regions were created, one of which is Western Visayas. Since then four more regions were created: Cordillera (CAR), the division of a single Region IV into Region IVa (Calabarzon) and IVb (MIMAROPA), Caraga and the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. The naturally most promising were and still are the NCR; Metro Cebu, the capital of the Central Visayas; and Metro Davao, the capital of Southern Mindanao. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the growth-pole strategy reduced in significance, while integrative thinking gained popularity. As a result of decentralisation in the early 1990s, regional authorities were encouraged to take the lead in fostering economic growth by connecting rural hinterlands and urban centres (the promotion of rural agro-industrial centres) and by connecting regions with each other through regional growth networks and corridors (Clausen Citation2010). A good example of this strategy has been the planning of nautical highways, a combination of highways and roll-on, roll-off ferries to connect the many islands of the archipelago.

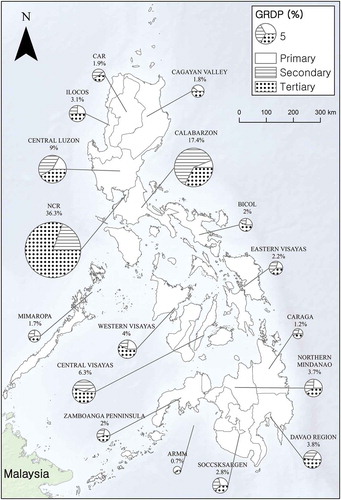

Despite all the efforts to create a more balanced regional development, Hill et al. (Citation2007, p. 41) observe that ‘there have been no major changes in Philippine economic geography over the past two decades; that is, the ranking of regions by socioeconomic indicators has changed relatively little’. The NCR continues to account for more than one-third of the gross domestic product, and spread effects have generated much economic activity and investments in the neighbouring regions of Central Luzon and Calabarzon as well (Clausen Citation2010). clearly shows the economic dominance of these three regions as opposed to the Visayas and Mindanao. Even Metro Cebu, often hailed as a successful secondary metropolis and model of endogenous development in Southeast Asia, has not been able to generate a significant number of spread effects to the rural areas of Central Visayas. Economic dynamism has been confined to the urban area. The Central Visayas’ gross regional domestic product (GRDP) remains much lower than Central Luzon’s.

Figure 1. Size and structure of GRDP in the Philippines.

Source: NSCB (Citation2013).

In an opinion piece by the Philippine Daily Inquirer (Citation2014), the lack of growth and development outside the core area is attributed to a government that has been Manila-centric for the past decades. Except for a few growth areas like Cebu and Davao, progress has become evident mainly in Metro Manila because the bulk of government infrastructure spending for roads and bridges, telecommunication and power facilities has been allocated to the NCR.

Indeed, studies conducted in the Central Visayas point out that private sector development and agribusiness have been successful in Metro Cebu (Van helvoirt Citation2014) but are difficult to achieve in other areas. Consequently, agriculture and manufacturing are relatively modest contributors to the GRDP in many non-core regions (). Partly as a result of the success of Metro Cebu (referred to as ‘Ceboom’ around the turn of the century) and experiences elsewhere in Pacific Asia, Philippine policymakers began to revisit the growth-pole concept, but connected to the trend of globalisation of Asian economic spaces, the increasing primacy of urban competitiveness and the growing importance of the services sector. Aside from the three existing growth poles of Manila, Cebu and Davao, nine other metropolitan areas have been created since 2000, one of which is Metro Iloilo, formally set up in 2006. The aim is to ‘build globally competitive metropolitan areas’ by a combination of attracting investments and improving the quality of urban living with respect to housing, social issues and environmental issues (NEDA Citation2007). The prime industry to lead investment and job creation in cities is IT-BPO. Approximately one million people work in this industry. However, 83% of the activity is concentrated in the NCR (BPAP Citation2012). Therefore, the Philippines has tried to trigger spread effects from the NCR and create IT-BPO employment in the so-called next wave cities programme. This is a programme initiated in 2009 led by the Business Processing Association Philippines and the Department of Science and Technology. It works together with government agencies and city governments in order to facilitate the establishment and growth of IT-BPO firms outside the NCR. Key issues concern office space, high-speed Internet and aligning the higher education system with the needs of the industry (BPAP Citation2012; Kleibert Citation2014). Eight Philippine cities are included in the global top 100 outsourcing destinations (Tholons Citation2014), including Iloilo City (91st) and Bacolod (86th). The strong focus of many cities’ governments on BPO also has its flaws since not all major Philippine cities can bet on offshore services. At present even cities situated in the periphery of the Philippine geo-economy seek to attract BPO firms, yet in the current global economic climate the demand for offshore services will not grow rapidly.

4. Research methodology and Iloilo City

Iloilo City was chosen since it is a vibrant city, a potential alternative to Manila and Cebu for (foreign) investments and employment generation, which has received little attention in the literature (See Kleibert Citation2014 for a study on two other cities banking on IT-BPO) The empirical analysis is based on 46 (semi-) structured interviews. The first part of the fieldwork was conducted in July and August of 2014 and consisted of 14 semi-structured interviews on general socioeconomic conditions and trends with key stakeholders from the private and public sector as well as regional journalists, 9 open interviews with ESL instructors and 3 interviews with Korean owners of ESL institutes. Questions pertained to trends in the regional economy, opinion on these trends, the viability of the IT-BPO and ESL industries, the socioeconomic situation of ESL instructors and related issues. In addition, secondary sources were compiled from government agencies and statistics offices. The second part was conducted in March 2015. This part entailed 18 semi-structured interviews with IT-BPO workers and 2 more interviews with Korean owners of ESL institutes. The interviews with the 18 IT-BPO workers were selected using the snowball sampling method. Most interviews were conducted in English, an official language that is widely spoken among people who completed high school and is widely used in the national media. The interviews with the five Korean businessmen were conducted in Korean. Employees in the IT-BPO sector were asked about their opinion of their jobs, working conditions and alternatives. The overarching aim of the (semi-structured) interviews was to assess the potential of the two industries under study as alternatives to the Philippine model of exodus capitalism.

It is important to note that virtually all IT-BPO employees as well as ESL instructors in Iloilo City are female (see also ). Besides the excellent command of the English language, a major advantage of doing qualitative research in the Philippines is the relative openness of interviewees. Most interviewees had no objection spending 30–60 min answering questions and were happy to share their (at times) critical opinion; likewise, civil servants were willing to disclose government policies and show relevant policy documents. In several other Southeast Asian countries, obtaining reliable information usually is more challenging, if not impossible, for foreign researchers without building trust over a longer period of time and cultivating social networks with influential people who can open doors. The remainder of this section briefly introduces Iloilo City as an offshore-services-led growth pole in the Philippines. All interviews were scrutinised by exploring common themes and keywords and vigorous cross-checking.

Table 1. Selected socioeconomic indicators.

Iloilo City forms the heart of the currently fast-growing metropolitan area that includes seven other surrounding towns. Iloilo City is the capital of both Iloilo Province and the Western Visayas, Region VI (see also ). The Spanish regarded Iloilo as strategically important and the city became a large trading centre in the nineteenth century. It was referred to as the ‘Queen City of the South’ around 1900, at the start of American control. It was also around that time that Iloilo was transformed from a textile centre into a services hub for the booming sugarcane industry in the Visayas (Funtecha Citation1997, pp. 152–155). However, since the general strikes of 1930s, Iloilo has gradually lost its status as the preeminent city of the Visayas to Cebu. Bacolod was also able to surpass Iloilo as the sugar hub. Iloilo suffered from disinvestments, strikes, a lack of strong local leadership and a lack of attention from the central government in Manila (Funtecha Citation1997, pp. 158–159). Since the mid-2000s, the services sector has been the main driver of the return to economic dynamism. In the last decade more than 15 large IT-BPO companies have opened an office in Iloilo (Personal communication with the chairman of the BPO Association of Iloilo, 2 August 2014).

shows that many women have found jobs in the services sector. Male college students in Iloilo usually focus on construction, seafarer’s jobs and engineering, fields in which communication in English language is less frequent than in finance, accounting, nursing and teaching that female college students take up. The Western Visayas correspondent for a major national newspaper, nevertheless, complained about a boom of ‘growth without inclusive development’. indeed demonstrates that from the perspective of Iloilo Province and the Western Visayas in general, much remains to be done to significantly increase living standards. The Western Visayas’ regional development plan calls for the region to strive for an economy to be ‘globally competitive driven by agribusiness and tourism sectors’ (RDC VI /NEDA VI Citation2011, p. 14), but several challenges are difficult to solve. Key informants often included the following four challenges: dealing with the stagnating sugarcane industry, providing decent work that can compete with jobs overseas, typhoons devastating rural livelihoods and crops (such as Fengshen – locally named Frank – in 2008 and Haiyan/Yolanda in 2013) and attracting sufficient numbers of tourists beyond the festival periods. With respect to the first three challenges, several respondents remarked, ‘Who wants to become a farmer these days?’ The decline of the sugarcane industry and the rise of the services sector in Iloilo City and Bacolod (Kleibert Citation2014), the capital of Negros Occidental Province, explain the increasing Gini coefficient between 2009 and 2012 (). Young graduates are employed in the city, whereas former sugarcane planation workers do not possess the necessary skills to find appropriate alternative work. In order to attract investors the Iloilo city government offers tax incentives, four special economic zones where BPO firms can locate; it has improved the electric power supply and is greening the city to attract middle-class white-collar workers. These enabling institutions and public service delivery enhancements could make Iloilo City a competitor of Cebu City (USAID Citation2014, pp. 19–20; The Philippine Star Citation2016). The next two sections investigate the extent to which Iloilo City is a genuine and viable offshore services-led growth pole in which employers and employees thrive.

5. IT-BPO; Iloilo City as a next wave city

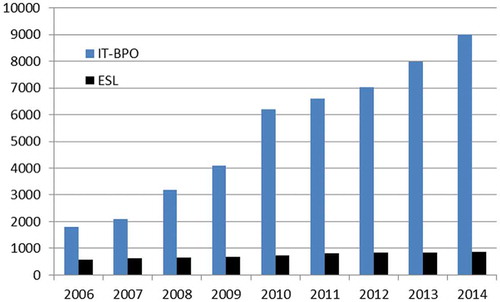

The first empirical case is concerned with the IT-BPO industry. India, with Bangalore as the main hub, is the global IT-BPO leader, followed by the Philippines. In 2013, the industry’s exports amounted to US$13.3 billion, substantially higher than the most important Philippine merchandise export – electronic integrated circuits and microassemblies, with an export value of US$9.4 billion in 2013 – but less than the US$23 billion of total remittances sent home by OFWs. At present, Iloilo City appears to be a dynamic city. In 2016, it was ranked as the eighth most competitive highly urbanised city in the Philippines out of 34 cities, based on economic dynamism, government efficiency and infrastructure provision (NCC Citation2016). It did especially well on government efficiency taking the third spot further indicating that the Iloilo municipal government facilitates private sector development. shows the remarkable growth of IT-BPO employment in Iloilo City. The chairman of Iloilo’s BPO Association gave the following explanation for investing in Iloilo:

Talent is Iloilo’s strength for BPO. People are very fluent in English, and the salary is much lower than Makati [the global services hub of the NCR] or Cebu. Iloilo’s office rent is also low, and we have enough office space. Our [local] government and mayor really care about the IT industry, more than others.

Many other key informants also pointed out one or more of the aforementioned enabling institutions and location factors, most frequently the talent pool due to thousands of new college graduates each year. Iloilo City hosts many universities and colleges and is the second-largest educational hub in the Visayas after Metro Cebu.

Furthermore, displays the global character of IT-BPO investments in the city, including a major investor from Bangalore and the emergence of more sophisticated activities besides call centres’ employees by early 2015. An example is the rising costs of health care in the USA, leading to the outsourcing of administrative functions to India and the Philippines. Unfortunately, the precise effects on indirect employment are difficult to quantify. Estimates in the Philippine media range from a multiplier of 1.5 to 4. Despite the dynamic growth of the IT-BPO industry in Iloilo, the interviews with employees in the call centre business reveal two challenges. First, although salaries are high for Philippine standards, working in a call centre is not a long-term option due to the ‘graveyard shift’: working from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. to accommodate foreign customers. Second, salaries abroad remain highly competitive (). Employment as a domestic worker in Hong Kong, for instance, is a common career path for Filipinas, even for women with a college degree. Those who find jobs abroad as office workers, teachers, or nurses, among other professions, obviously enjoy significantly higher salaries.

Table 2. IT-BPO firms in Iloilo, ranked by number of employees.

Table 3. Comparison of salaries for female employees in US$.

Consequently, many young women work temporarily in the IT-BPO industry while looking for better opportunities abroad as well as in Makati City where salaries are much higher and entertainment options lively and abundant. This result resembles Beerepoot and Hendrinks’ (Citation2013) work in Baguio City who found that offshore-services employees perceive their jobs as preparation for seeking greener pastures abroad. Most key informants have a positive attitude towards IT-BPO growth and the massive real estate developments of Megaworld Corporation, yet there are also some reservations. The editor-in-chief of the Daily Guardian, a regional newspaper based in Iloilo, for example, complained about a lack of regional endogenous development. The large employers mostly originate from Manila or abroad, while firms with headquarters in Iloilo only provide approximately 2000 jobs (). Interestingly, however, the latter group focuses on software development, an activity that requires higher skilled labour. This is exactly what the Philippine government envisions: similar to India moving away from call centres to higher value services such as software, health care, gaming and finance. In this respect the local start-ups are a positive development.

Within the Western Visayas, Bacolod is part of the next wave cities programme as well and therefore a competitor with respect to attracting domestic and foreign IT-BPO investors. Due to the declining sugarcane industry in Negros, occidental regional leaders started to consider offshore services as an attractive new job generator and impetus for regional development and regional renewal since the early 2000s. Bacolod started to attract investors earlier than Iloilo and has been successful in becoming a location for branches of NCR firms (Kleibert Citation2014). Yet Iloilo City appears to have been catching up in recent years, especially as far as the overall services sector is concerned. Growth of the IT-BPO industry has been phenomenal. The Iloilo Business Park project is set to establish Iloilo as a hub for IT-BPO. While the remittances economy remains the main driver of the Iloilo real estate boom (Philippine Daily Inquirer Citation2016), Megaworld Corporation, a big real estate developer from the NCR, aims to build a large amount of new office space for 24,000 BPO workers on the site of the old airport. Eventually, the business park should act as a major venue for the meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions (mice) industry. What is more, the city continues to attract a large number of college students; Iloilo’s leaders hope that the growth of the services sector and support services will be a reason for outside investors to stay and expand for the long run.

6. The ESL industry; a new niche

Like the IT-BPO industry, the ESL industry also reaps the benefit of the English language skills of the Philippine labour force. Teaching English to foreigners is a relatively small and new industry (Korea times Citation2009). Nationwide it employs approximately 20,000 face-to-face and online teachers and net sales amounted to US$150 million in 2013. In 2015 approximately 88,000 Koreans resided in the Philippines, many of them to learn English (CNN Citation2015). In Iloilo City, the number of teachers increased from fewer than 100 in 2000 to 860 in 2014 (); mostly women with excellent English language skills. As such employers draw personnel from the same talent pool and there is substantial labour mobility between the two sectors. Employers from both the IT-BPO and ESL share the interest of making Iloilo City a vibrant and liveable urban space. The overwhelming majority of youth coming to Iloilo to study English are South Koreans. Only 3 out of the 30 institutes also cater to Japanese and Chinese youth, predominantly for the online market. Young Koreans, often motivated by their parents and South Korean society’s eagerness to globalise, come to Iloilo for the following reasons: a lower cost of living compared to the NCR and Metro Cebu, a low crime rate and generally pleasant living conditions (relatively little pollution or traffic congestion). Several students had future plans or intention to study English in countries such as the USA, Canada and Australia after their time in the Philippines. Studying ESL in the Philippines is relatively cheap; it costs US$4000–5000 for 2 months in the USA but only US$2500–3000 in the Philippines. Thus it is more advantageous to study English in the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK once they have reached an intermediate level. In sum, the Philippines is often considered as a stepping stone for becoming a global citizen and for obtaining a college degree abroad in more ‘prestigious countries’. The Korean winter and summer vacations are busy seasons for the Iloilo ESL industry. Some institutes organise summer and winter programmes of 3–5 weeks for elementary and middle school students. These camps are composed of 8 hours study during weekdays and outdoor activities like a tour of Boracay during weekends. Another interesting feature of the industry is the Korean ownership of the institutes. The first Korean entrepreneur opened an English language school in Iloilo in 1994; others followed, especially between 2003 and 2008. There are two major ESL institutes in Iloilo city: NEO and MK. These two institutes cooperate with some Korean universities. Even a few Korean high schools and middle schools offer their students short-term English training courses in the Philippines, supported by the Korean government as part of wider curriculum policies.

The interviews with five Korean ESL businessmen revealed that they worry about current trends, especially in the face-to-face market. The Korean economy is not growing as fast as several years ago, and the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster also led parents to worry about the safety of their children in general. The owner of a small institute stated, ‘We are seeing a rapid decrease after the Sewol ferry disaster … Perhaps big institutes survive, but small businesses like ours can’t endure’. On the other hand, the online business is still growing. As a result, several owners are expanding in this market while downsizing the face-to-face business. This will enable them to focus more on Chinese and Japanese customers as well.

Like in Iloilo’s IT-BPO industry, the English teachers are mostly female. The nine employees interviewed agreed that salaries are good (). They also favourably compared the ESL industry to the IT-BPO industry because of the absence of the graveyard shift, flexible working hours (especially in the online business) and opportunities to make extra money by teaching online at home. Nevertheless, they complained about a lack of prospects to take their careers to a higher level, the patience required to teach Korean youth who have a low level of English language skills upon arrival, the repetitive and routine nature of the job and the small cubicle classrooms. Therefore, they certainly do not rule out working in a call centre and moreover they know working abroad as a domestic worker, administrative, finance or accountant assistant is an option () and thus they are constantly assessing their options, especially the young unmarried women. Thus the overall working environment is neither completely attractive nor dynamic. Furthermore, employment security is rather low. When some Korean ESL institutes closed their businesses, all instructors had to leave without any lay-off scheme or retirement pay. The interviewees even revealed a few cases of Korean businessmen running away to avoid liquidation costs and payment obligations. Again, the evidence does not support the observation of a truly viable and long-term alternative to overseas employment unless Korean and other entrepreneurs manage to tap into the Chinese and Japanese markets. The dependence on footloose outside investors in both the IT-BPO and ESL industry implies that growth and development are insufficiently driven by regional actors. Indeed, there is no guarantee that investors will stay in Iloilo for the long haul. They could easily shift operations once other cities and countries become more attractive. Ofreneo (Citation2015, p. 118) provides a stern warning as to what can happen and what partially is to blame for Philippine’s de-industrialisation:

With their investments focused on segments or parts of their global production, e.g., sewing garments, assembling toys, a big number of FDIs which came under EOI [Export Oriented Industrialization] turned out to have no long-term plans, much less programs to deepen and upgrade production, in the Philippines. Some are literally footloose investments, flying in and out of countries.

Therefore, creating a viable long-term offshore-services sector requires much effort from concerned stakeholders and a need to rethink concepts of endogenous development.

7. Discussion and conclusions

This article scrutinised the emergence of Iloilo City as an offshore-services growth pole in the Philippines. The empirical cases focused on the booming IT-BPO industry and the relatively new and small ESL industry, mainly catering to Korean university students. It assessed the accomplishments and challenges of (1) Iloilo City as a secondary city to be transformed into a growth pole prepared to compete more intensively in the geo-economic spaces of the Philippines and Pacific Asia and (2) the viability of offshore services to provide a truly decent employment alternative to the Philippine model of ‘exodus capitalism’ (Kondo Citation2014).

First, the results of the empirical investigation demonstrate that Iloilo City should be considered a genuine growth pole with a substantial degree of enabling institutions facilitating IT-BPO. Yet, two qualifications need to be made. While IT-BPO is booming, the ESL industry is still small and is heavily reliant on Korean university students and Korean businesspeople who own the ESL institutes. Furthermore, the urban exclusivity of offshore services and the next wave cities programme is worrying. There are no spread effects to the rural areas (Cai et al. Citation2012; Liu et al. Citation2016). The interviews with key stakeholders revealed that offshore services do not requires sourcing inputs from rural areas, and more importantly, it mainly recruits urban people who are fluent in English. Most young entrants in the labour market from rural areas in Iloilo Province do not possess sufficient English language skills. This could lead to more a more pronounced rural–urban divide and intraregional disparities.

Second, while banking on offshore services enables the Philippines to revive depressed urban areas, encourage regional deconcentration and to some extent modify the national urban system (Parr 1999a), it remains to be seen whether future growth of the IT-BPO ESL industries will result in attaining inter-regional balance () and providing a truly decent alternative to finding a job overseas. Despite all the efforts, the NCR continues to be the preferred IT-BPO destination, the turnover rate of employees in Iloilo City is high and there is no evidence of OFWs returning to Iloilo to find a job in either the IT-BPO or ESL industry (as can be increasingly observed in Makati City) (ABS-CBN Citation2014). Also, the envisioned shift from call centres to higher value offshore services might translate in higher skilled jobs but not necessarily in a massive growth of the number of jobs, especially given the continued competition of India. Concerned local stakeholders such as BPO firms and associations, city governments and real estate developers need to be aware of the changing opportunities and limitations. Stakeholders are well aware of the supply side but seem to be overly optimistic at times with respect to global demand prospects; see, for example, a report in the Manila Times (Citation2017) citing a revenue growth forecast of 9% until 2022. In addition to the global economic uncertainties related to the Trump presidency, most notably his urge to bring back jobs to the USA, the IT-BPO is also facing trends towards business process automation, artificial intelligence and advanced forms of computer–telephony integration. The rise of tech-enabled contact centres could potentially slow down the demand for BPO work in countries such as the Philippines and India (Business Mirror Citation2017).

What are the implications of the results for growth-pole strategies, theory and regional development? More work should be more oriented towards the study of labour markets across space. Many growth-pole strategies in developing countries have failed since it was assumed that employers and employees have the same objectives, an assumption that often does not hold given structural class, ethnic and religious cleavages within regions and localities as well as potentially different interests between various industries. The case of Iloilo has shown that employees do not view salaries and working conditions as perfect. They are well aware of alternatives in Makati City and abroad. In contrast, local government agencies seek to activate next wave cities by attracting offshore-services firms partly on the basis of lower wages compared to the NCR. In sum, growth-pole theories need to explicitly take into account labour market dynamics, especially in the context of developing countries characterised by a strong socioeconomic divide, if not divergence, between employer and employee interests and associated power asymmetries (the absence of opportunities to bargain collectively and improve labour standards).

Another implication relates to the absence of endogenous regional development (Stimson et al. Citation2011). Refinements of growth-pole and regional development theories could stipulate more precisely the interdependencies between exogenous and endogenous regional development. To what extent is endogenous growth a necessary condition for inclusive regional development in the medium and long run? What is the appropriate balance between exogenous and endogenous growth? How to align skills formation within the labour force with endogenous capacities and local innovation? What to do if a secondary city is not well positioned to spur endogenous growth? More research is warranted to address these issues.

Finally, in light of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) policymakers and practitioners could use the results of our work to better align the Philippine services sector to international economic trends. Although few national policymakers have been proactive with respect to thinking through potential repercussions for the services sector (Austria Citation2015; Nikkei Asian Review Citation2016; The Straits Times Citation2016), several regional stakeholders in Iloilo City have expressed a positive opinion of increased economic integration within Southeast Asia. For instance, according to the chairman of Iloilo’s BPO Association, ‘The Philippines should benefit from the growth of China and other Asian countries. We should be able to attract much more support services activity such as conferences, exhibitions, etc.’ Furthermore, increasing integration as part of the AEC could be a trigger to further expand the online ESL market by attracting youth from Southeast Asian countries. Learning online from Philippine instructors provides good value for money, particularly for middle class parents who cannot afford to send their children to Singapore, Australia and the USA.

The Philippines will remain to be a country that sends a large part of its labour force abroad, yet the services sector is the best-placed sector to start curbing the excesses of exodus capitalism – most notably split families in which children are raised by one parent or grandparents (Satake Citation2012: 63–90) – and instead to foster stronger and diversified linkages between exogenous Asian/global trends and endogenous regional capacities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Edo Andriesse

Dr Andriesse has researched Southeast Asia since 2000 and has fieldwork experience in Thailand, Malaysia, Laos, Indonesia and the Philippines. Currently he is interested in regional development with a focus on growth poles and rural development. He teaches a range of human geography courses at both undergraduate and graduate levels.

Jingu Kang

Mr Jingu Kang is a Master’s student at the Department of Geography of Seoul National University and has conducted fieldwork in the Philippines and assists the department with administrative tasks.

References

- ABS-CBN News. 2014. OFWs return home to find jobs at BPO. 24 Dec [cited 2015 Feb 22]. Available from: http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/global-filipino/12/24/14 /ofws-return-home-find-jobs-bpo

- ADB. 2012. Asian development outlook 2012: confronting rising inequality in Asia. Manila: ADB.

- Austria M. 2015. The Philippines and the AEC beyond 2015: managing domestic challenges. JSAE. 32:220–238.

- Beerepoot N, Hendriks M. 2013. Employability of offshore services workers in the Philippines: opportunities of upward mobility or dead-end jobs? Work Employment Soc. 0:1–19.

- Binns T. 2014. Dualistic and unilinear concepts of development. In: Desai V, Potter R, editors. The companion to development studies. 3rd ed. Abingdon: Routledge; p. 100–105.

- BPAP. 2012. Philippines IT-BPO investment primer. Makati City. http://www.ibpap.org/publications/research/investorprimer2012

- Business Mirror. 2017. Philippine outsourcing in 2017. [cited 2017 Feb 22]. Available from: http://www.businessmirror.com.ph/philippine-outsourcing-in-2017/

- Cai J, Yang Z, Webster D, Song T, Gulbrandson A. 2012. Chongqing: beyond the latecomer advantage. Asia Pac Viewp. 53:38–55.

- Clausen A. 2010. Economic globalization and regional disparities in the Philippines. SJTG. 31:299–316.

- CNN. 2015. Koreans say Philippines still the best place to learn English. [cited 2016 Dec 20]. Available from: http://cnnphilippines.com/videos/2015/04/17/Koreans-say-Philippines-still-the-best-place-to-learn-English.html

- Fan S, Kanbur R, Zhang X. 2011. China’s regional disparities: experience and policy. Rev Dev Finance. 1:47–56.

- Firman T. 1999. Indonesian cities under the ‘Krismon’: a great ‘urban crisis’ in Southeast Asia. Cities. 16:69–82.

- Funtecha H. 1997. Iloilo in the 20th century: an economic history. Iloilo: University of the Philippines Visayas.

- Hadjimichalis C, Hudson R. 2014. Contemporary crisis across Europe and the crisis of regional development theories. Reg Stud. 48:208–218.

- Hill H, Balisacan A, Piza S. 2007. The Philippines and regional development. In: Balisacan A, Hill H, editors. The dynamics of regional development: the Philippines in East Asia. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing; p. 1–50.

- Hosper G-J. 2005. ‘Best practices’ and the dilemma of regional cluster policy in Europe. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie. 96:452–457.

- Kannan K. 2007. Interrogating inclusive growth: some reflections on exclusionary growth and prospects for inclusive development in India. Indian J Labour Econ. 50:17–46.

- Kleibert J. 2014. Strategic coupling in ‘next wave cities’: local institutional actors and the offshore service sector in the Philippines. SJTG. 35:245–260.

- Kondo M. 2014. The Philippines: inequality-trapped capitalism. In: Witt M, Redding G, editors. The Oxford handbook of Asian business systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press; p. 169–191.

- Korea times. 2009. Koreans flock to the Philippines to learn English [cited 2015 Jun 29]. Available from: http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2009/09/117_51729.html

- Liu W, Dunford M, Song Z, Chen M. 2016. Urban-rural integration drives regional economic growth in Chongqing, Western China. Area Dev Policy. 1:132–154.

- Longhi C. 1999. Networks, collective learning and technology development in innovative high technology regions: the case of sophia-antipolis. regional Studies. 33:333–342.

- MacLennan M. 1965. Regional planning in France. J Ind Econ. 13:62–75.

- Manila Bulletin. 2014 Oct 2. Program to spur growth in Region 6 from OFW remittances launched.

- Manila Times. 2017. BPO revenues to outpace OFW remittances by 2018 – ING Bank. [cited 2017 Feb 23] Available from: http://www.manilatimes.net/bpo-revenues-outpace-ofw-remittances-2018-ing-bank/309043/

- Mercado R 2002. Regional development in the Philippines: a review of experience, state of the art and agenda for research and action. Discussion Paper Series No. 2002–03. Manila: PIDS.

- Myrdal G. 1957. Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- NCC. 2016. Cities and municipalities competitiveness index [cited 2016 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.competitive.org.ph/cmcindex/pages/rankings/#highly2016

- NEDA. 2007. Building globally competitive metro areas in the Philippines. Dev Pulse [cited 2015 Nov 16]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20131004221432/http://www.neda.gov.ph/devpulse/pdf_files/Devpulse%20factsheet%20-%20Aug%2030%20issue.pdf

- Nikkei Asian Review. 2016. Workers transfers slow ASEAN’s economic unification [cited 2016 Sep 26]. Available from: http://asia.nikkei.com/Politics-Economy/Economy/Worker-transfers-slow-ASEAN-s-economic-unification?page=1

- NSCB. 2013. Regional social and economic trends, Western Visayas. Manila: NSCB.

- Ofreneo R. 2015. Growth and employment in de-industrializing philippines. Journal Of The Asia Pacific Economy. 20:111-129.

- Parr J. 1999. Growth-pole strategies in regional economic planning: a retrospective view (Part 1. origins and advocacy). Urban Stud. 36:1195–1215.

- Perroux F. 1955. Note sur la notion de pôle de croissance. Economie Appliquée. 8:307–320.

- Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2014 Dec 3. Congested capital.[cited 2016 Sep 1]. Available from: http://opinion.inquirer.net/80633/congested-capital

- Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2016 Mar 18. Inquirer town hall series focuses on Iloilo economy.[cited 2016 Mar 20] Available from: http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/774828/inquirer-town-hall-series-focuses-on-iloilo-economy

- Planning Commission. 2013. Twelfth five year plan (2012–2017). New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- RDC VI /NEDA VI. 2011. Western Visayas regional development plan 2011–2016. Iloilo City: NEDA VI.

- Satake M. 2012. The impact of the global financial crisis on the Philippine economy: overseas dependency or alternative development. In: Venida V, editor. Global financial crisis in the Asian context: repercussions and responses. Quezon City: Ateneo Center for Asian Studies. p. 63–90.

- Sheng Y. 2012. The challenges of promoting productive, inclusive and sustainable urbanization. In: Sheng Y, Thuzar M, editors. Urbanization in Southeast Asia: issues and impacts. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies; p. 10–77.

- Silvey R. 2001. Migration under crisis: household safety nets in Indonesia’s economic collapse. Geoforum. 32:33–45.

- Stimson R, Stough R, Nijkamp P. 2011. Endogenous regional development: perspectives, measurement and empirical investigation. Cheltenham: Northampton.

- The Guardian. 2014. Philippines joyous as baby Chonalyn’s arrival means population hits 100m [cited 2015 Mar 5]. Available from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/27/philippines-chonalyn-baby-100m-population

- Ter Wal A. 2013. Cluster emergence and network evolution: a longitudinal analysis of the inventor network in Sophia-Antipolis. Reg Stud. 47:651–668.

- The Philippine Star 2016 May 30. Iloilo strengthens grip on BPO investments.[cited 2016 Dec 20]. Available from: http://philstar.com/cebu-business/2016/05/30/1588274/iloilo-strengthens-grip-bpo-investments

- The Straits Times. 2016. Talent war in Asean Economic Community: the Jakarta Post columnist [cited 2016 Sep 2]. Available from: http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/talent-war-in-asean-economic-community-the-jakarta-post-columnist

- Tholons. 2014. 2015 top 100 outsourcing destinations. [cited 2016 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.tholons.com/nl_pdf/Tholons_Whitepaper_December_2014.pdf

- Tyner J. 2004. Made in the Philippines: gendered discourses and the making of migrants. Abingdon: Routledge.

- USAID 2014. Industry study: Iloilo City. Investment enabling environment (INVEST) project [cited 2016 Dec 19]. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00K8KP.pdf

- Van helvoirt B. 2014. A relational view on regional development: the case of the electronics sector in Cebu, Philippines. In: Hutchinson F, editors. Architects of growth: sub-national governments and industrialization in Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Studies; p. 59–88.

- World Bank. 2009. World development report: reshaping economic geography. Washington (DC): World Bank.