ABSTRACT

This article aims to assess the links between urban resilience and resource efficiency challenges observed in the fast urbanisation contexts of Southeast Asian cities, taking Bandung (Indonesia), Iskandar Malaysia (Malaysia), Cebu (the Philippines), Bangkok (Thailand) and Hai Phong (Vietnam) as case studies. By showing that inefficient use of resources in the land use, water, energy and solid waste sectors is a critical factor of low urban resilience to natural disasters, this article makes a stronger case for the adoption of place-based policy frameworks such as urban green growth that can mobilise at the local-level synergies between resource efficiency and resilience across the aforementioned sectors. Finally, the article demonstrates that national government leadership and the mobilisation of urban communities are two potential strategic levers which can enable Southeast Asian cities to develop such vision and ensure its implementation.

1. Introduction: the need for evidence on the links between resilience and resource efficiency in Southeast Asian cities

1.1. Southeast Asia’s fast urbanisation context

In recent years, the concepts of urban resilience (or resilient cities) and resource efficient cities have gained root in the academic literature and global urban agendas, as climate change and limited natural resources have been recognised as priority development concerns. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 on cities aims to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ by 2030, and SDG 12 aims to ‘ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns’.

Urban resilience is defined as ‘the ability of cities to absorb, recover and prepare for future shocks (economic, environmental, social and institutional)’ (OECD Forthcoming Citation2017). In the context of climate change, it is understood as ‘the capacity of a city to absorb climate change-related disturbances/shocks while retaining the same basic structure and ways of functioning’ (Satterthwaite Citation2013). In parallel, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) defines a resource-efficient city as ‘a city that is significantly decoupled from resource exploitation and ecological impacts and is socio-economically and ecologically sustainable in the long-term’ (UNEP Citation2012). Other institutions and some research works have also adopted a broader approach to resource efficiency, including for instance financial and human resources.

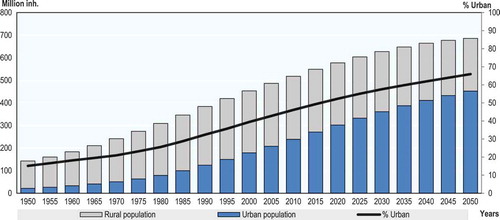

Looking at the urban resilience and resource efficiency challenges would be particularly instructive in the case of an emerging region such as Southeast Asia, where dynamic urbanisation and economic growth may significantly affect the capacity of cities to cope with shocks (in particular natural disasters) and to ensure sustainable use of resources. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs estimates that in only 35 years, from 1980 to 2015, the combined urbanisation level of the emerging Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)-5 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam) has increased from 29.5% to 51.4%, and is expected to reach 67.7% in 2050 (). In parallel, cities in the ASEAN-5 region have also experienced strong economic growth (OECD Citation2016a).

Figure 1. Urban versus rural population growth in ASEAN-5 (aggregated, millions)1950–2050.

Source: UN DESA (Citation2014), World Urbanisation Prospects, the 2014 Revision, New York.

1.2. Literature review: resilience and resource efficiency challenges in Southeast Asian cities

1.2.1. Southeast Asian cities face high risk of natural disasters

A large number of research studies indeed point out that while both population and economies grow, Southeast Asian cities are confronted with increasing risk of natural disasters. This includes among others droughts, heat waves, flooding, landslides, typhoons, tsunamis and earthquakes. The annual number of natural disasters in Southeast Asia has increased from 13 in 1970 to 41 in 2014, with a peak at 66 disasters in 2011. During this period, the human impact and economic losses due to these disasters have progressively increased to reach alarming levels ().

Figure 2. Evolution of the number of people affected by natural disasters in Southeast Asia and of economic losses 1970–2014.

(1) Total damage and total persons affected are smoothed calculations.(2) Total persons affected include persons requiring immediate assistance during a period of emergency, i.e. requiring basic survival needs such as food, water, shelter, sanitation and immediate medical assistance. It also includes homeless and injured people as a consequence of the disaster. It does not include people who died from the disaster.Source: Guha-Sapir et al. (Citation2016) EM-DAT: The CRED/OFDA International Disaster Database, Université Catholique de Louvain: Brussels, Belgium (available at: www.emdat.be).

The impacts of such natural disasters are felt in rural areas but also severely affect cities. A study placed Hai Phong, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City, Palembang and Jakarta among the world’s top 20 port cities with the highest proportional increase in exposed population by the 2070s, under a scenario taking into account climate change, subsidence and socio-economic changes. Bangkok and Ho Chi Minh City are also among the top 20 cities in the world with the highest proportional increase in exposed assets by the 2070s (Hanson et al. Citation2011). A concrete example is the 2011 flood that hit the Bangkok Metropolitan Region (BMR) and caused economic damages estimated at USD 23.9 billion in Bangkok city alone, and at USD 113.6 billion in Thailand overall (OECD Citation2016a).

1.2.2. Resources are being used at unsustainable rates or improperly managed at the local level

In parallel, a number of studies have highlighted the fact that fast urbanisation and economic growth characterising Southeast Asian cities have also led to unsustainable use of resources. This has been principally observed in four areas: land and natural habitats, water, energy and municipal solid waste:

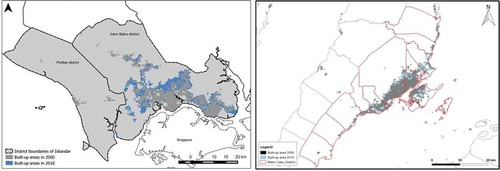

Land resources and natural habitats are being consumed at a fast rate. As demonstrated by Schneider et al. (Citation2015), urban land has increased by around 22% in East and Southeast Asia in only 10 years from 2000 to 2010. Based on this data, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has shown that in Iskandar MalaysiaFootnote1 and Metro Cebu for instance, the surface of urban areas has increased by 53.5% and 31.3% over this period, respectively (an annual growth rate of 6.7% and 2.7%) (). Much of Southeast Asia’s urban expansion has taken place in peri-urban zones, leading to the loss or degradation of natural assets such as mangrove forests, surface and ground water. In the BMR, urban sprawl has led to the disappearance of natural areas such as swamps, wetlands and land dedicated to agriculture (Snidvongs Citation2012; Marome Citation2013).

Water resources are being depleted and wasted. The Asia-Pacific’s water demand is projected to increase by 55% by 2050 to meet the growing need for domestic water and manufacturing in cities, among others, and around 3.4 billion people could be living in water-stressed areas (ADB Citation2016). In parallel, water sanitation infrastructure is also suboptimal and has not kept up with the pace of urbanisation. Currently, there is no or little centralised sewerage system in many Southeast Asian cities and waste water treatment plant capacity is inexistent or insufficient. Untreated waste water is generally discharged into grounds, drainage systems, rivers, canals or the sea, damaging precious ecosystems. In particular, the quality of surface water in rivers and canals, measured by the amount of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), is a serious environmental problem. In Bangkok city, BOD is as high as 30–50 mg/L in the densest urban areas (BMA Citation2012).

Energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are soaring. Energy demand increased by 50% between 2000 and 2013 in Southeast Asia, and is expected to increase by 80% between 2013 and 2040. Electricity demand from the power sector, in particular, is expected to triple during this period, from 789 to 2 212 TWh (IEA Citation2015). For example, total energy consumption in Iskandar Malaysia is forecasted to rise by 79.4% from 59.9 TWh in 2014 to 107.4 TWh in 2025 (Gouldson et al. Citation2015). In parallel, fossil fuels remain the privileged source of energy in all Southeast Asian countries. They accounted for 74% of primary energy demand in Southeast Asia in 2013, and this share is expected to increase to 78% in 2040 (International Energy Agency (IEA) Citation2015). The combination of fossil fuel use and increasing energy consumption has resulted in rising GHG emissions in the region.

Municipal solid wastes are fast increasing and improperly collected and treated (UN ESCAP and UN HABITAT, Citation2015). For example, in the Bandung Metropolitan Area, the amounts of municipal solid waste generated increased from 4320 tonnes per day in 2006 to 7661 tonnes per day in 2014 (a 77% total increase) (OECD Citation2016a). Such fast increasing quantities of solid waste generated have posed great challenges to local governments in collecting, handling and treating such waste. Waste collection services often do not reach all residents, especially slum dwellers. Waste generated in slums is often discharged openly in rivers and canals, as these urban populations tend to settle along their shores. In addition, Southeast Asian cities are poorly performing in terms of material recovery as landfills are the preferred treatment method (while only 5–20% of wastes actually need it) (UN HABITAT and UN ESCAP Citation2015). For instance, most wastes are sent to landfills in Bangkok city (77% of total waste), Bandung city (69%), Hai Phong (85%) and Metro Cebu (65%) (OECD Citation2016a).

Figure 3. Expansion of built-up areas in Iskandar Malaysia and Cebu, the Philippines 2000–2010.

Sources: OECD (Citation2016a), Urban Green Growth in Dynamic Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris.

1.2.3. The links between urban resilience and resource efficiency in Southeast Asia have not been sufficiently explored

While urban resilience and resource efficiency issues in Southeast Asia have been substantially covered in the literature, these two topics have however been less frequently discussed together in the context of this region. The links between energy consumption, GHG emissions and climate change mitigation have been extensively covered by the literature at a global level and are also relevant for Southeast Asian cities, but the links between resource efficiency (in particular in the sectors previously mentioned) and climate change adaptation in Southeast Asian cities have been less documented.

Brown et al. (Citation2012) have identified 10 action areas that cities in South and Southeast Asia must consider in order to build resilience to climate change impacts. The concept of resource efficiency is not explicitly mentioned but some of these 10 areas could fall in this category. For instance, the authors argue that climate-sensitive land use and urban planning, solid waste management, and water demand and conservation systems are among key strategies to build urban resilience which have been observed in a few cities of these two regions. Similar arguments about resource efficiency and resilience are developed by Friend et al. (Citation2016) and Promphakping et al. (Citation2016), among others, to explain Southeast Asian cities’ vulnerability to floods.

There is a need to further explore links that connect resource efficiency and urban resilience in the fast urbanisation context of Southeast Asia. While these studies have hinted that such links do exist and are strong, examples are either limited to a few cities or one or two specific sectors. In addition, there is room for more research on potential solutions to mobilise synergies between both challenges, including policy innovation and strategic, integrated frameworks. It also seems that the issue of policy implementation in the specific case of resource efficiency that can enhance urban resilience has been overlooked. Brown et al. (Citation2012), for instance, only briefly cover this topic, mentioning local governments’ lack of capacities and poor cooperation across sectors.

1.3. Research objective and methodology

1.3.1. Purpose of the research

The objective of this article is to expand knowledge on the potential links that unite resilience and resource efficiency in Southeast Asian cities, and to look at the potential strategies that could facilitate implementation of related policies. The following three research questions will be addressed throughout this article:

To what extent are urban resilience and resource efficiency linked in the particular context of fast-growing Southeast Asian cities?

How can co-benefits be best mobilised at the local level?

How can sound implementation of urban resilience and resource efficiency policies be ensured in Southeast Asia?

1.3.2. Methodology

This article answers these research questions through the lens of five citiesFootnote2 of the dynamic ASEAN-5 countries: Bangkok (Thailand), Iskandar Malaysia, Bandung (Indonesia), Hai Phong (Vietnam) and Cebu (the Philippines). The selection of the case studies was based on the OECD study Urban Green Growth in Dynamic Asia (OECD Citation2016a). Within the framework of this OECD project, these five cities were chosen so as to offer a diverse panel of urban areas facing rapid urbanisation and fast economic growth, and accounting for a significant share of national urban population. The study demonstrated that these cities also face high and increasing resource efficiency and resilience issues, as partially shown in the earlier literature review and in . The same cities therefore also offer opportunities to assess the links between both challenges, for the purpose of this article.

Table 1. Profile of the five case study cities.

The OECD’s case studies articulate the challenges that fast-growing Southeast Asian cities face, including urban resilience, and provide policy assessments and recommendations on how to advance green growth in these cities (OECD Citation2016a). Green growth is defined by the OECD as ‘fostering economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and the environmental services on which our well-being relies’ (OECD Citation2013a). However, these studies have a limited focus on resource efficiency, and the links between urban resilience and resource efficiency are not clearly discussed. In this regard, this article conducts additional investigation to fill this research gap. Urban resilience refers in this article to cities’ resilience to natural disasters, in particular floods that frequently affect the case studies. Resource efficiency refers to the optimisation of use of natural resources (water, electricity, fuel, land, solid waste), taking into account their lifecycle, for and by specific urban stakeholders and systems (e.g. industries, buildings, transport) and for the metropolitan area as a whole.

The findings presented throughout this article are elaborated based on the following:

A common questionnaire prepared by the authors and sent to each city to collect primary and secondary data. The questionnaire contains 50 questions and is composed of three sections: (i) socio-economic, environmental and infrastructure conditions in the city; (ii) national and local plans and policies; and (iii) governance structures and challenges. Each section contains a number of subsections containing specific questions related to resource efficiency and resilience. For instance, section i requests the case studies to provide information on local Gini coefficient, air pollution and GHG emissions trends, past natural disasters, urban sprawl, energy and water consumption, etc.

Semi-structured key informant interviews undertaken in each city between August 2014 and June 2016. The objective was to clarify answers to the questionnaire received beforehand, and to discuss face-to-face complex topics (in particular governance). During each field mission, representatives of the main local government branches were met, in particular the Mayor, departments related to spatial planning, environmental protection, transport, solid waste and water resources management, disaster response and municipal finance. The cities’ case studies do not possess any specific energy, climate change or green growth units. As often as possible, the city governments were also asked to invite national counterparts of each local department to the meetings. In addition, representatives of local communities and the private sector were invited; however, their participation could not be systematically ensured.

Five knowledge-sharing workshops organised in each case study city. The objective of these workshops was to discuss more in-depth specific issues which particularly affect each city (e.g. floods in the BMR). In addition, officials and experts from the other four case study cities and national governments also participated, in order to identify common issues shared by the case studies and different approaches and policies selected to tackle green growth, resilience and resource efficiency issues. Experts from development partners (e.g. JICA, Asian Development Bank), local universities, communities and the private sector were also invited and shared their thoughts and recommendations.

Data retrieved from international online databases and relevant academic and grey literature on resilience and resource efficiency in this region.

1.4. Structure of the article

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 demonstrates that urban resilience challenges identified in the case study cities can be directly traced to low resource efficiency. Based on these findings, Section 3 discusses strategies to effectively mobilise co-benefits between both objectives at the local level, in particular through local green growth policy frameworks. Section 4 examines national government support and involvement of urban communities as potentially critical strategies for the implementation of such integrated policy frameworks. Section 5 concludes with a summary of findings.

2. Low resource efficiency has increased risks of natural disasters in Southeast Asia

The research undertaken on the five case study cities points out to a combination of multiple factors behind their vulnerability to natural disasters. While some of them relate to climatic and geological conditions which characterise the region (e.g. monsoon season; low ground elevation in Bangkok, Hai Phong and CebuFootnote3), others can be directly traced to development patterns, including the poor use and management of the aforementioned resources in a context of fast urbanisation and economic growth.

2.1. Uncontrolled urban sprawl has lowered protections against floods and exposed the urban poor

Uncontrolled urban expansion has had direct consequences on Southeast Asian cities’ exposure and vulnerability to floods. Natural assets degraded or destroyed by new built-up areas used to play a pivotal role in protecting urban areas from floods by absorbing run-off and tidal movements, in particular mangroves, wetlands, agricultural land and forests. The loss of such natural land and natural floodplains was argued as one of the major causes of the 2011 flood that hit the BMR (Snidvongs Citation2012). In Hai Phong, the conversion of rice fields upstream in the northern branch of the Red River watershed for commercial and residential uses has significantly reduced rainwater retention and placed additional demands on Hai Phong’s storm water drainage system (City of Hai Phong Citation2015).

In addition, urban expansion has typically resulted in informal settlersFootnote4 occupying areas exposed to floods (river and canal banks, coastlines) and landslides (steep hillsides). This has been observed in all five case study cities. In Bangkok, the most affected populations from the 2011 floods were the urban poor, mainly because of their proximity to canals (NHA Citation2012). These findings are in line with the literature which has identified the links between vulnerability to climate change impacts and poverty in developing countries (Satterthwaite et al. Citation2007; Dodman & Satterthwaite Citation2008; Bicknell et al. Citation2009).

Further investigations on land-use planning and regulatory frameworks helped identify factors behind these development challenges. By and large, the five Southeast Asian cities lack a long-term vision and means of implementation promoting resource-efficient urban land use. Their rapid urban development has mostly been dictated by low densities and private motorisation. In Iskandar Malaysia, for instance, much new development such as Nusajaya area is characterised by low density and segregated land uses with built-up areas rapidly transformed from green fields. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of new residential construction in Iskandar Malaysia from 2004 to 2014 consisted of terrace housingFootnote5 (National Property Information Centre. Citation2015). In Metro Cebu, discussions with city planners revealed that the view that urban development should be guided by exclusionary zoning and not mixed-use development still prevails among some experts in charge of urban planning.

Generally, low priority has also been given to the development of public transport and Transit-Oriented Development principles, not only in the case studies but in many other Southeast Asian cities where virtually no public transport modes are available. Efforts to develop public transport networks are however underway in the five Southeast Asian cities. The Bangkok subway and high-elevated railway systems are being significantly expanded, for instance, and urban railway systems are under consideration in Metro Cebu, Bandung and Iskandar Malaysia.

In addition to the absence of strategies to contain urban sprawl and develop sustainable transport networks, the absence of risk-sensitive land-use planning is observed in all five cities. Spatial risk mapping, in particular, is largely underdeveloped. This also explains why zoning regulations are not functioning efficiently to build the spatial resilience of these cities to natural disasters.

2.2. The deterioration of water ecosystems has increased vulnerability to floods

The study of the five case study cities also highlighted the strong link between water resources management and resilience to floods. In Bangkok and Bandung, rising water demand for domestic and industrial purposes has partly been met through the private extraction of significant amounts of water from underground aquifers. Excessive and uncontrolled groundwater extraction has led to land subsidence in both cities, which in turn has increased urban exposure to floods due to lower ground elevation.

In all five case study cities, the clogging and burial of rivers under roads has also reduced the number and size of waterways which acted as natural conveyers of run-off in case of floods. In Iskandar Malaysia, for instance, the Sungai Segget River flowing through Johor Bahru has been buried under concrete for years. The destruction of natural resources such as mangrove forest and wetlands is also strongly related to water resources management issues, as they hold important ecological functions by absorbing water into the ground, replenishing local aquifers and therefore easing pressure on groundwater resources. This reaffirms the strong link between land use, water resources management and resilience to floods.

A critical factor which drives inefficient water resources management and therefore vulnerability to floods is that all cities have long failed to fully recognise the need to preserve water resources and the cycle of water with its resilience functions, and take necessary actions. However, the research points out to a growing acknowledgement of the need to manage water resources through ecosystem preservation, instead of traditional engineering approaches (Satterthwaite et al. Citation2007). Green infrastructure solutions,Footnote6 for instance, are increasingly introduced in some of the five case study cities. In the BMR, natural flood corridors have been identified at the metropolitan scale and are being incorporated into the latest local spatial plans: the objective is to provide a direct path to the sea for water run-off from northern Thai provinces, and to spare urban areas of the BMR from floods. While quantitative evidence on impacts of such green infrastructure projects is yet to come, they demonstrate high cost-effectiveness potential to increase both urban resilience and resource efficiency in cities, in comparison to more traditional solutions such as dams and levees ().

Table 2. The benefits of green infrastructure for urban resilience and resource efficiency.

2.3. Efficient and sustainable management of energy resources can contain natural disaster risk in the long-term

Links between energy and urban resilience were not observed as directly as in the previous two sectors, in particular in terms of adaptation to natural disaster risk.Footnote7 However, efficient and sustainable management of energy resources is strongly connected to GHG emissions and global changes in climate patterns that may increase the likelihood and intensity of climatic and geological events leading to disasters in Southeast Asian cities (changes in rainfall patterns, higher frequency of cyclones, sea level rise, droughts, etc.). Containing and reducing the consumption of fossil fuels at the local level would not only be a strategy to promote resource efficiency but also to mitigate natural disaster risk and ensure urban resilience in the long term. In addition, there is increasing interest in the role of cities to contribute to climate change mitigation, in particular rapidly growing cities in middle-income countries (IPCC Citation2014; Gouldson et al. Citation2015).

Rising electricity consumption and strong reliance on fossil fuels in the five Southeast Asian cities analysed lead to rising GHG emissions, thus a higher contribution to climate change and further risk of natural disaster. The research reveals that subnational governments in Southeast Asian cities do not consider energy efficiency and renewable energy development challenges as part of the local policy agenda. None of the five cities indeed have dedicated energy departments, and while Bangkok, Hai Phong and Metro Cebu have adopted climate change action plans, energy management measures remain broad in scope and concrete implementation is very timid. One of the reasons of poor local involvement in energy resource management is the traditional responsibility of national governments in this sector. Central governments have demonstrated stronger leadership through the adoption of major energy development plans, but have largely failed to recognise the role cities can play (see Section 4). This echoes existing research claiming that cities generally ‘lack the requisite information, supportive national-level policies and access to financing’ in the energy sector (ESMAP Citation2012).

This is a critical missed opportunity, as some studies have demonstrated that climate change actions in such cities can have high impact and be cost-effective. The research undertaken by Colenbrander et al. (Citation2016), for instance, has shown that a range of low-carbon options in Johor Bahru (the main city in Iskandar Malaysia) could significantly reduce per capita emissions while generating significant annual savings and paying back investment in a short period of time.

Some innovative practices are nonetheless emerging in the building and renewable energy sectors in the case study cities, but the impacts remain to be seen. Green building codes are being experimented, for instance, in Mandaue City in Metro Cebu.Footnote8 Bandung city has announced that a green building certificate will be a requirement and not simply a recommendation for obtaining a city building permit, but the policy is still under consideration. Likewise, renewable energy facilities are increasingly deployed in these five cities. In Bangkok, the first waste-to-energy (WTE) plant just started operating. WTE technologies present not only the advantage of reducing the need for fossil fuel to produce energy, but also offer an alternative to traditional solid waste treatment methods such as landfills.

2.4. Poor solid waste management has undermined the efficiency of drainage facilities

Solid waste management is also found to significantly affect the resilience of the five Southeast Asian cities at study. Uncollected solid waste is responsible for the clogging of drainage facilities that are supposed to evacuate water run-off in case of heavy rainfalls. This is one of the causes of the failure of the drainage system in many Southeast Asian cities.

Many factors are interrelated with each other that explain poor solid waste management in these Southeast Asian cities. Uncollected solid waste clogging drainage facilities tend to be dumped by informal settlers living along river banks or the coastline, because these urban populations do not have access to formal municipal collection services. In addition, efforts to limit waste generation at source and to reuse waste are still underdeveloped in all five cities.

The analysis of the five cities nonetheless helped identify existing initiatives that may alleviate poor solid waste management and increase their resilience to natural disasters, if replicated at a larger scale:

Composting is commonly put in practice to reduce waste: in Bandung city and Hai Phong, for instance, composted waste accounts for 24% and 12.5% of total waste treated. The composted waste serves as fertiliser for household gardens and peri-urban farms. However, poor waste segregation limits the impact of these initiatives;

Cebu city is promoting waste separation at source, through its policy of ‘No segregation, No collection’ which compels waste sorting at source with penalties for non-compliance. This is a good starting point for emulation by other cities to begin a proper waste management and recycling practice. The benefit for sorting at source should enable a drastic reduction in the final quantity of residues needed to be permanently landfilled;

In Bangkok and Bandung, the mobilisation of local communities has been experimented as a solution to compensate for the lack of formal municipal collection services in low-income communities. The schemes are particularly efficient and have the advantage of providing local governments with opportunities to raise awareness of and reach out to the urban poor (see Section 4).

3. Integrating urban resilience and resource efficiency into local green growth policy frameworks

3.1. Adopting place-based policy frameworks tapping on diverse sectoral opportunities

The local character of urban resilience and resource efficiency challenges (and their links) identified in the previous section calls for the development of place-based policy frameworks integrating both objectives. The concept of place-based policy frameworks was developed by the OECD to stress the importance of taking account of geography and the specific locations of resources, and the fact that ‘spatially-blind’ national policies are less likely to achieve coherent, multi-sector policy outcomes if ignoring local specificities (OECD Citation2011).

In addition, the previous analyses pointed out to the multiple links that exist not only between urban resilience and resource efficiency, but also across different sectors. Land use, for instance, is an anchor for other sectoral policies. The development of green infrastructures, which provide benefits in terms of water resource management and resilience to floods, requires a proactive spatial strategy making space for and preserving such natural resources. Studies have also highlighted the strong correlation between densities and transportation energy requirements (Weisz & Steinberger Citation2010). Similarly, WTE facilities benefit both solid waste management and sustainable energy generation.

These findings reinforce the conclusions of existing studies that stressed the need for integrated planning processes and approaches to resilience based on urban systems (Brown et al. Citation2012; da Silva et al. Citation2012). In the case studies, however, urban resilience has been understood as a technical or environmental issue, rather than as a cross-cutting principle of a sustainable urban development agenda. For example, the cities of Hai Phong and Bandung’s efforts to enhance urban resilience largely focus on enhancing coordination between the fire and police departments, and less on broader ‘whole-of-government’ initiatives mobilising diverse sectoral opportunities. In Bangkok and Cebu, greater recognition of the interplay between climate change adaptation and resource efficiency has been observed, partly owing to more intense natural disasters that have hit these two cities. However, there is room for the adoption of a more comprehensive vision for urban resilience and resource efficiency, backed by institutions ensuring internal coordination and more efficient implementation of existing plans (see Section 4 for more details).

3.2. The case for urban green growth policy frameworks

Beyond the recognition of the need for a cross-sectoral strategy, this article argues that the concept of urban green growth offers opportunities to integrate these synergies in a single overarching vision for the long-term development of fast-growing Southeast Asian cities. The OECD defines urban green growth as fostering economic growth and development through urban activities that reduce negative environmental externalities and the impact on natural resources and environmental services (OECD Citation2013a). Other international organisations such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank have adopted a slightly different definition and approach to (urban) green growth, in particular due to diverging opinions on the importance of the social dimension within the concept. However, there is a broad consensus about its meaning (Bowen Citation2012). As a comprehensive approach integrating objectives of resource management and urban resilience across a range of sectors, the concept of urban green growth offers an umbrella under which policy synergies and complementarities can be mobilised. provides a summary of sectoral policies which can generate resource efficiency and resilience at the local level, and which can be integrated into urban green growth policy frameworks.

Table 3. Review of main policies mobilising synergies between urban resilience and resource efficiency, with identified practices in Southeast Asia.

4. Assessment of governance strategies in implementing integrated policy frameworks for urban resilience and resource efficiency agendas in Southeast Asian cities

Section 4 discusses how governance strategies can further support implementing integrated policy frameworks towards urban resilience and resource efficiency in Southeast Asian cities. In this regard, the research has identified that leadership of national governments and mobilisation of urban communities are two critical policy levers to lift implementation obstacles.

4.1. National governments’ leadership is critical for the development and implementation of integrated green growth strategies at national and local levels

4.1.1. Recognising the role of cities in national green growth and climate change policy plans

In developing countries, national governments have strong influence on the development of cities through national development plans and strategies. Each of the ASEAN-5 national governments has elaborated a general economic and social development plan, and in most cases sectoral plans in green growth sectors or in related cross-cutting fields such as climate change (OECD Citation2016a). Most of these national plans required local governments to translate them into local plans and therefore affect policy decisions taken by cities.

A detailed analysis of ASEAN-5 countries’ national policies revealed that Vietnam and Indonesia are the only two countries having developed a specific green growth strategy at the national level. While all national governments have developed climate change action plans covering adaptation objectives, these plans have unequally addressed the questions of resilience and resource efficiency at the local level. The Philippines’ National Climate Change Action Plan (2011–2028) acknowledges the need for natural resources efficiency to enhance local adaptation in the sectors covered previously, but the emphasis is much weaker in the case of Malaysia and Thailand’s plans, in particular. In this perspective, it is urgent that national governments in Southeast Asia develop or revise country-wide green growth and climate change policy frameworks addressing these two objectives across all relevant sectors, as shown in .

In addition, it is observed that national governments have not explicitly recognised the role that cities can play in achieving national green growth/climate change goals, and thus not articulated it in their national policy frameworks. The exception is Vietnam: among the 12 measures laid out by the National Action Plan on Green Growth for the period 2014–2020, Action 11 (to develop green and sustainable urban areas) specifically targets urban actions. In addition, Action 2 requests some provinces and cities to formulate a local Green Growth Action Plan. As a consequence, Hai Phong is the only city having developed its own green growth action plan. Identifying the role cities can play for urban resilience and resource efficiency, and providing the necessary resources (e.g. through earmarked transfers for urban resilience and resource efficiency) could have strong impact, in this regard.

4.1.2. Developing metropolitan approaches to urban resilience and resource efficiency

Urban development patterns and resource efficiency and resilience issues in the case studies are commonly occurring beyond the core city’s jurisdictions into urban vicinities. However, the policy frameworks in the five cities also highlighted that coordination among local governments in the five metropolitan areas has been weak. Formal and informal forms of horizontal collaboration, including metropolitan planning for green growth, are absent or largely underdeveloped.

Land use, water resources management and flood risk are typical, interconnected urban resilience and resource efficiency challenges that bear a metropolitan dimension. For instance, in the BMR, flood risk management is a major metropolitan coordination issue. The failure to contain and minimise the damage from the 2011 floods partly owed to the lack of coordinating mechanisms at the metropolitan scale. Similarly, the development of the Bus Rapid Transit which is only being designed and implemented in Cebu City, despite metropolitan commuting flows, may create expensive infrastructure lock-in (and rising GHG emissions) that will be difficult to circumvent in the future.

Considering their authority and resources, national governments can play a central role in fostering metropolitan governance and thus a more efficient action for resource efficiency and resilience at the local level. They can indeed create incentives for metropolitan coordination and directly encourage the creation of metropolitan forms of governance. The Federal Malaysian Government for instance played a central role in the establishment of the Iskandar Regional Development Authority, which now plays a strong role in sustainable development at a metropolitan scale. While more initiatives for metropolitan coordination are emerging in the region (e.g. Metro Cebu Development Coordinating Board (MCDCB), Bandung Metropolitan Area Coordinating Body), the success of such governance mechanisms will largely depend on what levels of authority and capacities they are endowed by the national governments.

4.2. Community-based actions are promising strategies for resource efficiency and resilience

4.2.1. The benefits of community involvement for solid waste management and disaster preparedness

At the district level, the case studies reveal potential benefits of involving more systematically urban communities in order to meet integrated urban resilience and resource efficiency objectives. More generally, the academic literature has also demonstrated that involving local communities for resilience in developing countries can help to tackle governments’ low capacity (Satterthwaite Citation2013).

The analysis of initiatives and needs in the five ASEAN-5 cities suggest that the most promising areas for community involvement (with regard to resource efficiency and urban resilience) are solid waste management and disaster prevention and response. The following initiatives, in particular, have been observed:

In Bangkok, the Thailand Institute of Packaging and Recycling Management for Sustainable Environment has created the ‘Zero-Baht shop’ concept, a cash-free barter system that allows the trade of recycled materials in communities for necessities, goods and services. After separating the collected recyclables by type and bringing them to a ‘Zero-Baht shop’, garbage collectors receive an invoice to be exchanged for goods and services of the same value, or to be deposited it into a ‘bank’ as savings. The collected recyclables are sold to junk collectors and the income is used to create a welfare fund and provide services to the garbage community members, such a medical care (TIPMSE Citation2014).

In Metro Cebu, some Local Government Units (LGU)s are making use of the purok system, a microstructure of a Barangay (the smallest LGU) that promotes empowerment of communities and effective governance at the sub-village level (urban or rural). This system has been first set up in the Comodes Island and later used in Liloan and San Francisco municipalities. The scorecard developed by MCDCB to assess LGUs’ governance performance tends to indicate that LGUs using this system perform better than those without it. It is used for instance to enhance solid waste management and mobilise local communities faster in case of natural disaster.

4.2.2. Structuring and leveraging communities’ participation

While the general tendency in the five Southeast Asian cities is an acknowledgement of communities’ potential contribution and importance in the city’s life, their involvement remains poorly organised. In its vision Bandung Collaborative Society (City of Bandung Citation2015), the city of Bandung mentions the presence of more than 5000 communities in the city, but these are not well identified, organised and mobilised. Another concrete example is waste scavengers, which are participating in the waste collection process in Bandung but whose role in waste recovering activities has not been well recognised (Damanhari et al. Citation2009) nor incentivised through benefit mechanisms. The municipality may therefore need a more systematic approach to identify urban communities of different types and provide targeted support depending on policy objectives such as urban resilience and resource efficiency.

An option for local governments in order to mobilise more effectively local communities could be to create a coordination unit for civil society organisations (CSOs) to encourage citizens’ participation in resource efficiency and resilience efforts, assist in community actions and manage mechanisms of dialogue. A CSO coordinating mechanism could be particularly helpful given the growing size of many cities in Southeast Asia, the local authorities’ lack of resources, and the many potential contributions of local communities.

5. Conclusion

This article has demonstrated that inefficiency and improper management of land and natural habitats, water, energy and solid waste resources is a major factor of natural disaster risk in Southeast Asian cities, and therefore that urban resilience and resource efficiency are strongly interconnected. Our assessment of the five cities shows that a number of innovative policy practices are emerging at the city level to enhance urban resilience and resource efficiency in an integrated manner. However, such practices remain limited to certain policy areas and to certain cities and have not delivered significant impact yet.

Because of such strong interlinks, addressing urban resilience and resource efficiency agendas in an integrated manner can create synergies and result in enhanced policy efficiency, and local governments are particularly well positioned to do so as these two concepts possess a strong place-based dimension. Adopting place-based and cross-sectoral policy frameworks, such as urban green growth, thus appears to be a potentially efficient strategy for the sustainable long-term development of fast-growing Southeast Asian cities. At the moment, none of the five cities have adopted such comprehensive vision for development.

This article also examined what obstructed the development of such strategic frameworks and more generally what governance initiatives could effectively support resource efficiency improvements and urban resilience. The analysis has shown that leadership of national governments and involvement of urban communities are two powerful levers for policy implementation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Loïc Daudey

Loïc Daudey has been working as a Junior Policy Analyst on Urban Green Growth in the Regional Development Policy Division of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since 2013. Mr. Daudey has four years of professional experience in the field of sustainable urban development, with a focus on Southeast Asian cities. At the OECD, he has co-authored a series of studies within the framework of the project Urban Green Growth in Dynamic Asia. Before joining the OECD, he worked for Clean Air Asia, an environmental NGO based in Manila, the Philippines, on air pollution and sustainable urban transport solutions in Asian cities. Mr. Daudey holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Social and Political Science and Master’s Degree in Urban Policy and Governance, both obtained at the Paris Institute of Political Science (Sciences Po Paris).

Tadashi Matsumoto

Tadashi Matsumoto (Project Manager, Urban Green Growth / Knowledge Sharing, Regional Development Policy Division, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) leads urban green growth work at the OECD and manages OECD’s Green Cities Programme. His current project, the Urban Green Growth in Dynamic Asia project, aims to explore effective policy and governance strategies in the rapidly urbanising cities in Asia through the case studies of Bangkok (Thailand), Iskandar Malaysia (Malaysia), Hai Phong (Vietnam), Bandung (Indonesia), and Cebu (Philippines). Tadashi has contributed to a number of urban research projects including Green Growth in Cities (2013), Compact City Policies: A Comparative Assessment (2012)and Cities and Climate Change (2010). Prior to joining the OECD in 2009, he was engaged in urban planning, housing and building policies at the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism for more than ten years. He holds a MUP (Urban Planning) from New York University and Ph.D. from Tokyo University (Engineering). He also studied at the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm. He currently lectures at Tsukuba University, Japan, and SciencesPo, France

Notes

1. The figures presented in this sentence do not include urban areas in the Pontian District, which is partly included in the official territory of Iskandar Malaysia.

2. The unit of analysis of the five cities is the metropolitan areas (Bangkok Metropolitan Region, IM, Bandung Metropolitan Area, Hai Phong and Metro Cebu).

3. Two-thirds of Metro Cebu’s population and 85% of Hai Phong’s urban areas are located in low-lying areas

4. UN HABITAT defines informal settlements as ‘residential areas where 1) inhabitants have no security of tenure vis-à-vis the land or dwellings they inhabit, with modalities ranging from squatting to informal rental housing, 2) the neighbourhoods usually lack, or are cut off from, basic services and city infrastructure and 3) the housing may not comply with current planning and building regulations, and is often situated in geographically and environmentally hazardous areas’ (UN HABITAT and UN ESCAP, Citation2015).

5. Terrace house referring to a style of medium-density housing where a row of identical or mirror-image houses share side walls.

6. Green infrastructures are defined as ‘a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services (OECD Citation2015). It incorporates green spaces (or blue if aquatic ecosystems are concerned) and other physical features in terrestrial (including coastal) and marine areas’ (European Commission, Citation2013).

7. Exploring the links between the efficiency of power networks and resilience to natural disasters would be a potentially interesting area for research in this regard but was not addressed by the research.

8. A green code extends beyond minimum code prerequisites and incorporates features beyond the range of the model energy codes. It provides direction for construction and development to ensure it is less impactful and more sustainable (USDE Citation2012).

References

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2016. Asian water development outlook 2016, strengthening water security in Asia and the Pacific. Mandaluyong City, The Philippines, Asian Development Bank.

- Bicknell J, Dodman D, Satterthwaite D. 2009. Adapting cities to climate change: understanding and addressing the development challenges. London (UK): Earthscan.

- BMA. 2012. Bangkok state of the environment 2012. Bangkok: Department of Environment.

- Bowen A. 2012. Green growth: what does it mean? In: Environmental scientist. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics. London, United Kingdom.

- Brown A, Dayal A, Rumbaitis del Rio C. 2012. From practice to theory: emerging lessons from Asia for building urban climate change resilience. Environ Urbanisat. 24(2):531–556. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- City of Bandung. 2015. Building a collaborative society. City of Bandung. Bandung, Indonesia.

- City of Hai Phong. 2015. Green growth promotion plan of the city of Hai Phong, in collaboration with city of Kitakyushu.City of Hai Phong. Hai Phong, Vietnam.

- Colenbrander S, Gouldson A, Heshedahl Sudmant A, Papargyropoulou A, Chau LW, Ho CS. 2016. Exploring the economic case for early investment in climate change mitigation in middle-income countries: a case study of Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Clim Dev. 8:351–364.

- da Silva J, Kernaghan S, Luque A. 2012. A systems approach to meeting the challenges of urban climate change. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 4:125–145.

- Damanhari E, Wahyu IM, Tri Padmi RR. 2009. Evaluation of municipal solid waste flow in the Bandung metropolitan area, Indonesia. Cycles Waste Manage. 11:270–276.

- Dodman D, Satterthwaite D. 2008. Institutional capacity, climate change adaptation and the urban poor. IDS Bull. 39:67-74.

- European Commission. 2013. Green Infrastructure (GI) - Enhancing Europe's Natural Capital. COM/2013/0249 final. Brussels: European Commission.

- ESMAP. 2012. Energy efficient cities initiative. Washington: World Bank, Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme.

- Friend R, Choosuk C, Hutanuwatr K, Inmuong Y, Kittitornkool J, Lambregts B, Promphakping B, Roachanakanan T, Thiengburanathum P, Thinphanga P, Siriwattanaphaiboon S. 2016. Urbanising Thailand: implications for climate vulnerability assessments. Asian Cities Climate Resilien Work Paper Ser. 30:2016.

- Gouldson A, Colenbrander S, SUdmant A, McAnulla F, Kerr N, Sakai P, Hall S, Papargyropoulou E, Kuylenstierna J. 2015. Exploring the economic case for climate action in cities. Global Environ Change. 35:93–105.

- Guha-Sapir D, Below R, Hoyois P. 2016. EM-DAT: the CRED/OFDA International Disaster Database. Brussels: Université Catholique de Louvain. Available from: www.emdat.be

- Hanson S, Nicholls R, Ranger N, Hallegatte S, Corfee-Morlot J, Herweijer C, Chateau J. 2011. A global ranking of port cities with high exposure to climate extremes. Clim Change. 104:89–111.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). 2015. Southeast Asia energy outlook. IEA Publications. Paris.

- IPCC. 2014. Climate change 2014 – IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Cambridge (UK): Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change/Cambridge University Press.

- Marome W. 2013. Urban risk and vulnerabilities of coastal megacity of Bangkok, Thailand. In: Proceedings of the 4th Global Forum on Urban Resilience and Adaptation. Bonn, Germany; [ cited May 31–June 2].

- National Housing Authority. 2012. GIS-assisted approach in housing development for low-income earners. In: GIS Section, Department of Housing Development Studies, presentation made to the delegation from SUDU. Bangkok: UN ESCAP.

- National Property Information Centre. 2015. Property Stock Report 2015. Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia.

- OECD. 2011. OECD regional development outlook: 2011 edition. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2013a. Green growth in cities. Paris: OECD Green Growth Studies, OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2015. Water and cities - ensuring sustainable futures. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2016a. Urban green growth in dynamic Asia. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. Forthcoming 2017. Resilient cities. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/gov/regional-policy/resilient-cities-report-preliminary-version.pdf

- Promphakping B, Inmuong Y, Photaworn W, Phongsiri M, Phatchanay K. 2016. Climate change and urban health vulnerability. Asian Cities Climate Resilien Work Paper Ser. 31:2016.

- Satterthwaite D. 2013. The political underpinnings of cities’ accumulated resilience to climate change. Environ Urban. 25:381–391. doi:10.1177/0956247813500902

- Satterthwaite D, Huq S, Pelling M, Reid A, Romero-Lankao P. 2007. Adapting to climate change in urban areas: the possibilities and constraints in low- and middle-income nations. London (UK): IIED, Human Settlements Discussion Paper Series – Climate Change and Cities.

- Schneider A, Mertes CM, Tatem AJ, Tan B, Sulla-Menashe D, Graves SJ, Patel NN, Horton JA, Gaughan AE, Rollo JT, et al. 2015. A new urban landscape in East–Southeast Asia, 2000–2010. Environ Res Lett. 10:034002.

- Snidvongs A. 2012. Flood and urban risk/vulnerability management. Thailand: Presentation made at the Science-policy Dialogue on Challenges of Global Environmental Change in Southeast Asia; 19-21 July; Bangkok.

- TIPMSE. 2014. Presentation at the Bangkok knowledge sharing workshop on urban green growth in dynamic Asia, 6–7 August. TIMPSE. Bangkok.

- UN DESA. 2014. World urbanisation prospects, the 2014 revision. United Nations. New York City.

- UN HABITAT and UN ESCAP. 2015. The state of Asian and Pacific cities 2015: urban transformations; shifting from quantity to quality. United Nations. Bangkok.

- UNEP. 2012. Sustainable, resource efficient cities – making it happen. United Nations. Paris.

- USDE. 2012. Green Building Codes; [cited 2016 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.energycodes.gov/development/green/codes

- Weisz H, Steinberger JK. 2010. Reducing energy and material flows in cities. Environ Sustain. 2010:185–192.