ABSTRACT

In this article, we discuss the possibilities for and challenges to the urban planning process at the neighbourhood level, from the perspective of the right to the city. We focus on the 2 de Julho, a neighbourhood located in the Old Centre of Salvador, Bahia (Brazil), where processes of gentrification have pressed the local population to demand its own neighbourhood plan. We problematise neighbourhood planning from the radical perspective of the right to the city, in its potential to generate a collaborative process that originates ‘in-conflict’ and as an instrument of negotiation vis-a-vis the state. We argue that neighbourhood planning not only promotes autonomy and self-management, but also contributes to making the State more accountable. In this way, it has the potential to subvert conventional urban practices that reproduce socio-spatial exclusion, inequalities and injustices whilst contesting the neoliberal logic that dispenses the state from its social responsibilities.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this article is to discuss how neighbourhood planning can contribute to the ‘right to the city’ for a population affected by gentrification processes caused by recent changes in the economy and real-estate developers driving urban restructuring. Our discussion is based on a neighbourhood planning experience in 2 de Julho, a historic neighbourhood in the old centre of Salvador, Bahia (Brazil), where urban restructuring processes are taking shape through corporate and State actions driven by an urban-space gentrification and privatisation rationale.Footnote1 One of the main actions is the ‘Santa Teresa Cluster’, a government-supported project designed in 2007 by the private sector for the neighbourhood, where approximately 50 properties – including grounds, ruins and houses – were acquired to be transformed into lofts, hostels, hotels, shops, restaurants and offices. This private project was then reformulated by the Municipal government in 2012 under the name of ‘Santa Tereza Neighbourhood Humanisation Project’ (Projeto de Humanização do Bairro Santa Tereza) that would not only change the name of this historic neighbourhood, but also profoundly transform its makeup.

In opposition to this process, different social groups, residents and visitors of 2 de Julho, have brought about collective actions, including the request by the Our-Neighbourhood-is-2-de-Julho Movement (Movimento Nosso Bairro é 2 de Julho_MNB2J)Footnote2 to elaborate a Participatory Neighbourhood Plan. This was attended to by the research group ‘Lugar Comum’ (Common Place) from the Faculty of Architecture of the Federal University of Bahia (FA-UFBA), and was initiated in January 2014 with the aim of developing a neighbourhood plan with propositions that would reflect local needs and demands.

The possibilities and challenges that we argue this participatory neighbourhood plan holds for the right to the city are based on the planning process experience itself, as a University Extension Project that aims to promote dialogue and collaborative work between the university and the community.Footnote3 This research also builds upon the critical urban studies and urban geography literatures, which discuss the right to the city from the Lefebvrian perspective, as in Mitchell (Citation2003), Purcell (Citation2002, Citation2013), Souza (Citation2010) and Harvey (Citation2012).

From this perspective, our work aims to shed light on the processes and practices that enable and limit the right to the city, understood as the residents’ right to use, access and effectively contribute to the production of their urban space. Survey results by Mourad (Citation2011) and Mourad et al. (Citation2014) were used to analyse the gentrification processes in Salvador’s Old Centre, drawing from and adding on to the literature on urban restructuring processes in Brazil by Arantes (Citation2000), Vainer (Citation2002), Maricato (Citation2002), Rolnik (Citation2006) and Fernandes et al. (Citation2016), amongst others.

2. The 2 de Julho neighbourhood: what kind of a place is this?

2.1. Location

The Municipality of Salvador does not have an official updated mapping of neighbourhood boundaries,Footnote4 but 2 de Julho can be located within the institutional Administrative Region plan. In this regional subdivision, the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood is part of a sub-area included in Administrative Region I – Centre, as defined by Municipal Law No 7,400/2008 that puts into effect the current Municipal Master Plan 2008 (Salvador Citation2008) for the Municipality of Salvador. The neighbourhood is also part of Salvador’s Old Centre, the boundaries of which were established by Salvador’s Old Town Bureau of Reference (ERCAS Citation2010).

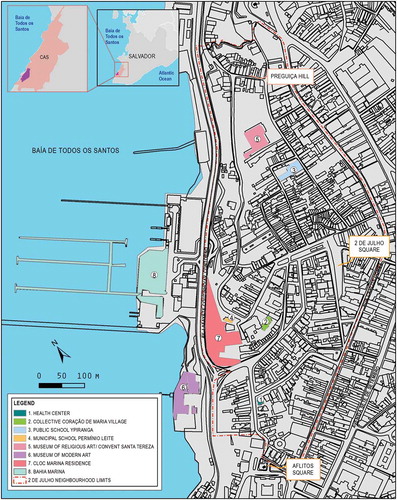

In the absence of an official demarcation of the neighbourhood boundaries, we considered – for an approximate reckoning of the area’s urban characteristics – the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood outline defined by the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan through interviews realised with 259 residents.Footnote5 By adopting this outline, we seek to advance towards a concept of Neighbourhood that neither superposes to nor is restricted by the administrative-region boundaries. In this view, the neighbourhood is understood as constituted by an everyday living space, where social neighbourhood relations occur and people get close to each other. Moreover, this mapping reflects the social diversity, customs and occupations of the people who live in and use this urban setting, based on their activities ().

Figure 1. ‘Localisation of 2 de Julho Neighbourhood, Salvador’s Old Centre (CAS), Salvador (BA)’. Source: based on map of Salvador (Datum: SAD 69 UTM Zona 24s) and primary research data collected in 2014–15 by 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Planning Project.

In that sense, we understand a neighbourhood as a place, which Milton Santos defines as:

a framework for a pragmatic reference to the world – in which solicitations and precise requests for conditioned actions intervene – but it is also the irreplaceable theatre of human passions – from which stem, through the act of communication, the most diverse manifestations of spontaneity and creativity. (Santos Citation2008, p. 322, our translation)

This understanding recalls, to some extent, a classic reference, i.e. the concept of the neighbourhood unit, formulated by US sociologist, Clarence Perry. For this author, the neighbourhood unit relates to the allocation and location of primary education facilities, recreational areas and local shops – which should be at walking distance from people’s homes (Hall Citation2007). Another convergent formulation is Angelo Serpa’s (Citation2007), who sees the neighbourhood ‘…as language and discourse […] since its boundaries vary and are perceived in different ways by its residents, who “build their own neighbourhood” as a basis for daily strategies of individual and collective action’ (p. 28).

Everyday practices taking place in the neighbourhood also engender emotional connections to the living and dwelling space. Geographers, sociologists and urbanists have studied the affective aspects as an important dimension for the production of such places (Soja Citation1989; 2006; Thrift Citation2007; Jones and Evans Citation2007). According to this approach, neighbourhoods are built by transforming such connections into people’s disposition or ability to take actions. For example, the feeling of belonging (or exclusion) on the part of the residents towards their neighbourhood can encourage acts of solidarity or instigate territorial conflicts that do not necessarily play out on a larger scale. Thus, the neighbourhood can become a privileged place for the realisation of the right to the city, as these differentiated socio-spatial relationships increase the possibilities of appropriation of space – by its residents.

2.2. Population and income

According to the 2010 Census data from IBGE [The Brazilian Geography and Statistics Institute], the 2 de Julho neighbourhood had then a population of 5,235 residents – averaging 2.4 dwellers per household, well below Bahia’s State average of 3.5. Of this total, 46% were men and 54% were women. As for age groups, it is to be noted that adults formed the majority of the population (with 65% of all considered denizens in the 30–59 age bracket). In terms of race, the incidence of black and mixed race people was 67%. Economically, 2 de Julho is a predominantly low-income neighbourhood, as 62% of households have a monthly income of up to three times the minimum wage (IBGE Citation2010).Footnote6

In terms of employment, 2 de Julho residents hold a range of different formal and informal occupations and represent a diversity of social groups: artists, students, intellectuals, foreigners, bohemians, small business owners, the poor and the homeless. The neighbourhood stands out for holding one of the few outdoor markets in the Old Town, for its street sellers and unpretentious shops, cultural and political events, popular bars and restaurants – frequented by different generations and social classes – lively colours and smells, and children playing in squares and up and down the hilly streets – with breath-taking views onto Salvador’s All Saints’ Bay. Nonetheless, the continuing existence of this social diversity in the neighbourhood is at a serious risk.

In recent years, the neighbourhood real-estate market appreciation associated with the gentrification process has become a threat to the permanence of its historically disadvantaged population, a significant part of which is composed of tenants. IBGE’s 2010 Census data indicate that the neighbourhood had a total of 2,196 permanent households that year, most of which, i.e. 71% of the considered universe, living in apartments. Close to half of the residences (about 47%) were rented, with an almost equal proportion (48%) of owned residences (IBGE Citation2010).

2.3. Urban attributes

As regards institutional urban-planning provisions associated with the 2 de Julho neighbourhood, it lies within the Urban-Renewal Macro Area, characterised by having infrastructure and utility networks available, albeit in great need of maintenance and refurbishing. The 2 de Julho neighbourhood is part of an area appreciated for its relevant symbolic, historical and cultural features, associated with Salvador’s Old Centre and the All Saints’ Bay – and holding significant patrimonial real-estate assets. Part of the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood is registered by the UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. This Neighbourhood is thus clearly distinguishable from the rest of the city, and has great symbolic significance. It was also declared a Strict Preservation Area (Salvador 1983, paragraphs 107–110) as well as a Cultural and Landscape Protection Area (APCP) (Salvador Citation2008, paragraphs 229–32).

The 2 de Julho neighbourhood is situated in a privileged location, in terms of its connections to the municipality’s street network, public transportation system and shipping facilities. Its residents have relatively easy access to the various services, activities and infrastructure which are available in Salvador’s Old Centre. The coverage of basic sanitation and electricity services in the neighbourhood is high with 99.8% of its residences having access to the city-network water supply, 98.1% to a city-sewer or runoff system connection, 99.9% to regular garbage collection and 100% to the electrical grid (IBGE Citation2010). As such, the 2 de Julho neighbourhood has significant urban features and a prominent location in the City of Salvador. The gentrification processes affecting the neighbourhood have to do with – amongst other issues – disputes over territorial claims.

3. The Santa Tereza Cluster: a gentrifying act in the 2 de Julho neighbourhood

Several authors (e.g. Arantes Citation2000; Maricato Citation2002; Vainer Citation2002; Rolnik Citation2006; José Citation2007; Mourad Citation2011; Fernandes et al. Citation2016) warn that in Brazil – especially in large cities – the redevelopment of central areas has been characterised by gentrification processes, promoting the attraction of new types of activities and residents, economic reinvestment, a change in image and meaning, environmental improvement and ‘social cleansing’, i.e. the expulsion of poor residents from the areas of intervention (Mourad et al. Citation2014).

A recent example of these processes is witnessed in the way the 2 de Julho neighbourhood has changed, following the implementation of the Santa Tereza Cluster. The Cluster is a project devised for the neighbourhood by two developers – Eurofort Patrimonial and RFM Participações. In 2007, these private operators demarcated a 15-hectare built-up urban-fabric area within this sector of Salvador’s Old Centre, partially overlapping the area declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1985. In recent years, private investors have purchased approximately 50 properties – in the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood and surrounding areas – including grounds, ruins and houses, to be transformed into lofts, hostels, hotels, shops, restaurants and offices (Mourad Citation2011).

For Hamnett (Citation1991, p.175), gentrification is:

[…] Simultaneously a physical, economic, social and cultural phenomenon. Gentrification commonly involves the invasion by middle-class or higher-income groups of previously working-class neighbourhoods or multi-occupied “twilight areas” and the replacement or displacement of many of the original occupants. It involves the physical renovation or rehabilitation of what was frequently a highly deteriorated housing stock and its upgrading to meet the requirements of its new owners. In the process, housing in the areas affected, both renovated and unrenovated, undergoes a significant price appreciation.

Smith (Citation1987) explains the gentrification process through the rent gap (i.e. income disparity) concept, drawing on the analysis of divestment and reinvestment data for built-up areas. Gentrification thus occurs when the discrepancy (‘gap’) between current and potential land value is wide enough to generate satisfactory returns for the developers. ‘The crucial point about gentrification is that it involves not only a social change but also, at the neighbourhood scale, a physical change in the housing stock and an economic change in the land and housing market’ (p. 463).

Many of the aspects that characterise gentrification are featured in the implementation of the Santa Tereza Cluster, in the 2 de Julho neighbourhood. As Mourad notes (Citation2011), it all begins with an economically devalued yet attractive centre. This combination of devaluation and attractiveness in the same area has been made into a business opportunity by private entrepreneurs. In the dilapidated, abandoned buildings, investors see favourable profit-making conditions – that is, idle real-estate capital assets characterised by low profitability, which equates to a devaluation of both public and private built-up wealth.

4. Economic changes in the 2 de Julho neighbourhood: unique real estate appreciation through private appropriation of collective territorial features

In an intentional and sophisticated way, the Santa Tereza Cluster developers chose and marked out a specific area covering many popular, symbolic and treasured features: the Museum of Sacred Art, the historic Euterpe’s Puppet Carnival Club (known as Fantoches), the area’s topography itself – a hillside with a breath-taking view of All Saints’ Bay – and 2 de Julho square, which has been, the traditional ending to the Bahia Independence parade route. These unique urban elements provide the right conditions for a regeneration project to be developed within the gentrification model. The historical and cultural attributes of the Old Centre and the All Saints’ Bay are thus mobilised to build an image, capable of leveraging a marketing strategy and attracting investors (Mourad Citation2011).

The attempt at acquiring this particular area generated a speculative real estate appreciation process that threatens the permanence of 2 de Julho’s economically weaker population. Such an appreciation is clearly revealed by the survey we carried out at the Salvador City Hall Finance Department (Sefaz) on title transfer transactions. It shows an acceleration of real estate property transactions in the neighbourhood, with a progressive increase in their value.

Take for instance the 14 units making up the Row adjacent to the Museum of Sacred Art: purchased for BRL 5,000 in July 2007, marketed for BRL 17,000 in August 2007 and then resold one year later for BRL 114,000 (each). Another piece of property – the 4,759.17-sq-m area where the Cloc Marina Residence has been constructed – sold for BRL 380,000 in 2001, but in 2007 was purchased for BRL 6,000,000 by developer CJ Construtora e Incorporadora Ltda. – thus increasing its value 15.8 times in a 5-year period. The value of the property reflects the kind of buyer that the project intends to attract – far more affluent than the low-income local population needing a place to live. This property mark-up also pushes local rents up (Mourad et al. Citation2014).

5. Gentrification effects on the 2 de Julho neighbourhood

According to Slater (Citation2006), for gentrification studies to maintain their critical perspective, it is necessary to focus not only on the roots of gentrification, but also on the analysis of its perverse effects; particularly, with regard to the exclusion, segregation, expulsion and eviction of the disadvantaged populations. With this in mind, the Santa Tereza Cluster is unmistakably an act of gentrification that threatens the social rights and permanence of the population living in and using the Old Centre area. It becomes part of a trend to replace pauperised populations and intensify socio-spatial segregation through the purchase of inhabited buildings by private agents, institutional expropriations, arbitrary evictions by public officials and high rents. The Santa Tereza Cluster boundaries marked out a subdivision of the 2 de Julho neighbourhood, resulting in a polarised concentration of resources and leading to the intensification of segregation and spatial and urban inequalities.

The real estate located next to the Museum of Sacred Art – an ancient row belonging to the Archdiocese of Salvador – was purchased and Santa Tereza Cluster developers began project execution by evicting the population. The area, acquired to make way for the luxury TXAI design hotel, previously comprised 14 houses, inhabited by low-income residents. Residents of Coração de Maria Row (Vila Coração de Maria), on Democrata Street, have been living under similar threats of eviction. The St. Peter Brotherhood of Clerics – owner of the buildings – filed an act to repossess the property, which puts the permanence of the residents at risk – including that of the 86-years-old tenant, Mrs. Anita Ferreira Sales, who has maintained upkeep on the property for 45 years. Vila Coração de Maria is set in a strategic position, adjacent to the Cloc Marina Residence, which is part of the Santa Tereza Cluster.

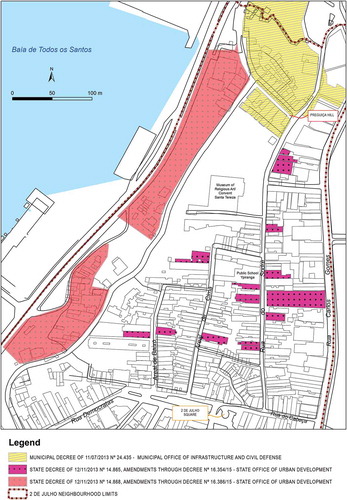

More recently – in late 2013 – another issue concerned the area, as Salvador’s Old Centre was the target of five decrees for the expropriation of several properties for public use. The 2 de Julho Neighbourhood was directly affected by three of these decrees: one by the municipality (Salvador 2013) that declared public use as the reason for the expropriation of 57 properties, on the grounds of a redevelopment project to be carried out in and around the Preguiça Community; and two by the State GovernmentFootnote7 (Bahia Citation2013a; Bahia Citation2013b), affecting 24 and 67 buildings, respectively – both intended, on paper, for the historical, cultural and economic rehabilitation of Salvador’s Old Centre.

No public debate, hearing or consultation was held to present any of these redevelopment projects to the public – which proves that a deficit of participation exists amongst the residents of the Old Centre areas who would be directly affected by the decrees. This attitude ignores the general guidelines of the City Statute (Brasil 2001), which set as an urban policy goal the full development of the city and urban-property social functions, through a democratic management process driven by public participation in the formulation, implementation and monitoring of urban development plans, programmes and projects (item II of art. 2).

With regard to the purpose of the expropriations, though they are intended – according to the aforementioned state decrees – for preservation, conservation and/or refurbishment of buildings, in order to allow for the historical, cultural and economic rehabilitation of Salvador’s Old Centre, their actual destination and specific use is not declared. This is a serious issue, because there are within this area about 1,500 buildings identified as empty or underutilised, although no urban-planning tool is being applied for them to fulfil their social functions – which reveals overt property speculation under way.

Along with the expropriation threats that are mainly affecting people and families who belong to the neighbourhood’s most socially and economically disadvantaged groups, those deemed to be the most ‘disagreeable’ – i.e. drug users or the homeless – have already suffered the ongoing effects of gentrification. An intervention by Salvador Municipal officers, called ‘Order in the House’, took place in November 2013 – with the support of the Military Police, the Municipal Guard and 170 men from virtually all municipal agencies. It resulted in the removal of about 70 people from dilapidated houses, and the destruction of many of the buildings they occupied. This social cleansing occurred on and around Preguiça Hill, a historically marginalised neighbourhood area inhabited by low-income black families, also known as a hotbed of drug trafficking and characterised by a considerable presence of homeless and substance-dependent people.

As a counter to this process of gentrification, a number of social groups, residents and people who frequent the 2 de Julho neighbourhood promoted collective actions, amongst which was the request by the Movement Our-Neighbourhood-is-2-de-Julho (MNB2J) to design a Participatory Neighbourhood Plan.

6. The experience of the 2 de Julho neighbourhood planning

6.1. Neighbourhood plans

Urban planning at the municipal level – commonly known for the resulting Municipal Master Plans (Planos Diretores) – has been heavily criticised in Brazil, for failing to contribute to reducing urban and socio-territorial inequalities and exclusion in Brazilian cities. Municipal Master Plans are blamed for mostly responding favourably to the demands of capitalist groups in urban production, whilst ignoring – at least in their implementation – the demands of the historically marginalised populations, who have been fighting for social and territorial justice for decades. Even after the City Statute was approved, in 2001 – establishing democratic management as a structural element in urban policy design and requiring citizens’ participation at all levels of public policy decision-making – recent urban planning and management experiences have shown that little progress has been made in its implementation.

Some authors (e.g. Villaça Citation2005; Maricato Citation2011; Rolnik Citation2011) highlight important factors that contribute to the ineffectiveness and lack of credibility of municipal urban planning. Amongst such factors is the inability of city administrators to implement Municipal Master Plans, which, as noted by Villaça (Citation2005, p. 90) ‘stems from the chasm between their discourse and our municipality’s administration practices, and from the inequality that characterises our political and economic reality’. According to Maricato (Citation2011), top-down urban planning – as done in current practices – cannot integrate the conflicts inherent in society and the disputes between its different actors. Existing social conflicts are usually not considered in Municipal Master Plans, which refer to unimpeded and peaceful scenarios.

The experience of public discussions on Salvador’s Municipal Master Plan, throughout 2007, revealed how difficult it is to mobilise the population – and ensure effective popular participation in the debate on where to head in city planning. The main criticisms of the process referred to the difficulty of access to the technical studies supporting the plan and the chosen methodologyFootnote8for participation, in addition to the lack of incorporation of new content or criticisms and suggestions for changes into the plan. Consistent low public attendance was also a feature of this process, as very few people would usually show up at public hearings, generally due to insufficient dissemination or inappropriate schedules.

In this context, the Neighbourhood Plan came about as a way to potentially overcome some of the existing limitations in the Municipal Master Plan preparation and implementation process, especially with regard to technical and political confrontations that come up locally. This is a process that Vainer et al. call Conflict-Based Planning, ‘which wagers on the ability of conflict-related processes to constitute collective subjects capable of occupying the public scene in an autonomous way’ (Citation2013, p. 17, our translation). Thus, urban planning, highly criticised for its ideological weight and ineffectiveness, is used here as a tool to address the conflict.

It is understood, in this case, that the best place for the practice of participatory urban planning – which addresses the right to the city – is where daily life and living physically occur: the neighbourhood, thus acknowledged as a space to be appropriated (Carlos Citation2004). The neighbourhood is also a territory where the right to the city can be made factual, for being a ‘glocalised’ place (Swyngedouw Citation2004), where local living intersects with social and economic processes of a different scale – substantiated in the form of local contradictions, conflicts and potential.

In our view, thus, participatory neighbourhood planning – bringing residents to front stage – allows for greater local involvement in the discussions during the drafting process. It also allows for deeper discussions, thus opening the possibility of incorporating existing conflicts between different social groups, active either within the neighbourhood or on other levels. Consequently, this is also a way to better understand how the subjects involved are benefited or harmed by the on-going local processes – as well as how and why this occurs.

6.2. 2 de Julho neighbourhood planning

The proposal for the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan arose following collective actions by the neighbourhood’s social groups, residents and people who frequent or inhabit the area. They try to respond to strong urban-space privatisation trends, and uphold their demands – clustered around neighbourhood improvements and the defence of local people’s rights. Such demands included the elaboration of a ‘popular’ Neighbourhood Plan that the MNB2J had started drafting, but soon had to abandon due to lack of resources. Neighbourhood planning was later made possible through a FA-UFBA extension project, in January 2014. This experience thus shows the possibilities and challenges that neighbourhood planning offers as a local collaborative project between the university and the neighbourhood residents, independent of State or private interests.

In this view, the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan aims towards the expansion and systematisation of knowledge about the neighbourhood, the political strengthening and technical training of the people involved, and towards the collective construction of guidelines for its full development – be it under a social, cultural, economic, political or environmental perspective. The process of developing a Neighbourhood Plan represents a possibility of mediating a different kind of territorial pact. This brings about the opportunity for the collective construction of strategies, to knit together such issues as public spaces, social diversity, technical and social infrastructure, community facilities, adequate housing and integration with city life, in order to articulate the many activities, uses and occupations that define such space (Fernandes Citation2013).

The reflections on the possibilities and challenges for the right to the city through the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan date back to when it was conceived, in 2013, as the associated UFBA extension project was being prepared. In the first year of plan implementation,Footnote9 advancements were made in systematising and expanding neighbourhood knowledge, and in strengthening the political and technical capacity of the organisations and social movements involved. This was done through the collection of primary-data (from questionnaires, technical field visits, workshops and meetings with neighbourhood leaders and residents) and secondary-data (from academic production, technical reports and records of public administrative offices), as well as through a process of social mobilisation that involved the production of virtual and physical informative material (e.g. blog, banners, flyers, folders, videos). Aside from surveying local potentials, problems and material needs (i.e. access to and improvement of goods and services), some of such activities were designed to retrieve and encourage emotional memories and collective dreaming of the neighbourhood. The plan also involved the collective construction of guidelines and proposals during workshops with residents that were held in different parts of the neighbourhood and at different times along the process (). Propositions were also collected during interviews with 174 residents and in ‘dream boxes’ that circulated in some of the key neighbourhood’s public and commercial establishments over more than a year’s period.

Figure 2. ‘Dreams, Propositions and Projects Workshop in 2 de Julho, Salvador, 2014’. The second workshop focused on the dreams, proposals and projects of residents, state and private initiative, for the neighbourhood. A large map was used for the residents to locate their dreams and propositions for the neighbourhood, identifying also their agents. This workshop was held in the neighbourhood public state college ‘Colégio Estadual Ypiranga’ on 26 April 2014. Photo by Camila Brandão.

Figure 3. ‘2 de Julho Residences under Municipal and State Expropriation Decrees, Salvador, 2016’. Note: based on a map elaborated by the 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Planning Project in 2016 to inform residents about the expropriation process. The map was part of a leaflet that contained information about the rights of owners, renters and squatters and potential ways to mobilise them. The material was disseminated through door-to-door actions, workshops, websites and local meetings.

The most concerning issues for the participants were: public insecurity, which residents directly related to a high crime rate; infrastructural problems, especially improper sewage and water canalisation system that was related to increasing outbreaks of vector-born diseases such as dengue, zika and chikungunha; the lack of green areas and increasing depredatory practices of the municipality towards the few remaining trees found in the city centre to make space for their reform projectsFootnote10; and the need to protect the most disadvantaged groups from the perverse effects of the gentrification process, amongst other matters.

The participation of various groups and representatives from different segments of the local population was essential to the collective construction of the neighbourhood plan drafting process. As several authors point out (Mouffe Citation2000; Watson Citation2003; Calderon Citation2013), it is important not to pursue the need for consensus in discussions and collective decision-making – as understanding unequal power relations and accommodating conflicts and disputes are essential and constructive for the participation process. Thus, the Neighbourhood Plan team was responsible for identifying, discussing and disseminating opinions and divergent proposals, contributing – whenever possible – to building covenants relating to these conflicts and differences – whilst considering the actual possibility that such an understanding may never come to be. Therefore, following Vainer et al. (Citation2013), the Neighbourhood Plan – outside being a tool of vindication – also aimed to serve the population as a tool for the full disclosure and management of conflicts.

A concern that permeated the 2 de Julho experience and constituted a major challenge throughout its development was the difficulty in mobilising the population, in order to ensure effective local participation during the whole planning process. The reasons for this difficulty were of different orders, many of which corresponded to Calderon’s (Citation2013) case studies’ observations, e.g. the inability to maintain an ongoing dialogue with the community and involve it in all the activities of the Neighbourhood Plan; the difficulty of dialoguing with the variety of groups and social segments found in the neighbourhood; the fact that many individuals were unwilling to participate in public-interest discussions; a disbelief in urban planning on record for historically not being implemented; a tendency for groups or individuals to take on leadership behaviours in debates, inhibiting the participation of others; and, a lack of competence and professional knowledge on how to include local people in the planning process.

Within this perspective, collective actions were taken along the planning process as conflicts related to the right to the city arose within the neighbourhood. For example, one of the major conflicts of interest that emerged at the outset of the planning process was the publication of state and municipal expropriation decrees (mentioned above), which threatened the permanence of the most disadvantaged part of the neighbourhood population. In response, the Neighbourhood Plan team and the MNB2J joined forces to inform the local population about their rights and pressurise the municipal and state governments through judicial representation at the Public Ministry and the convening of meetings with government representatives asking for justification of such measures and demanding for the protection of people’s rights; especially, their rights to decent housing, transparent information and participation as stated in the Brazilian Constitution and City Statute ().

In May 2015, another of such conflicts arose following the death of one resident of the Preguiça community caused by the collapse of colonial houses left abandoned for real-estate speculation. Soon after, government agents sent a notice to many of the community residents prompting them to emergently evacuate their houses alleging that these were also under risk of collapse. In response to such unjustified drastic measures, joined action between the Neighbourhood Plan team, the Articulation of Social Movements and Communities of Salvador's Old CentreFootnote11 and the residents of the Preguiça community led to the formulation of a technical report that made evident the inadequacy of such measures for the majority of the houses under notice and pointed to the urgent need of restoration of two houses on the Preguiça Hill that were under imminent risk of collapse. These reports were then used in meetings with State representatives to uphold these demands.

This three-year process of collaborative neighbourhood planning resulted in the construction of 43 propositions grouped in 10 different themes.Footnote12 For each proposition was identified the proposed place of intervention, the responsible agents, the potential beneficiaries and the modes of action to implement them. Most propositions (21%) were localised in the Preguiça area, the most disadvantaged and marginalized sector of the neighbourhood. Almost half of them (48%) had the State as the main responsible agent for implementation and 22% of the demands indicated an articulation between the community and the responsible governmental institutions as a preferred mode of action. The propositions included the creation of green spaces and recreational areas for kids and elders; the planting of trees throughout the neighbourhood; the creation of urban gardens; the demand for social housing to ensure the permanence of low-income residents; the creation of a day-care; and a special care centre for homeless and substance-dependent people using vacant/underutilised land,Footnote13 amongst other matters. In its final form – as a written technical report and a community folder – the Neighbourhood Plan is meant to serve as an instrument for the residents to uphold their demands towards the State and as a guide for community action and self-management. At the moment of writing this article, the Neighbourhood Plan was at its final stage, being prepared for the presentation of the final results to the community.

7. Possibilities and challenges to the right to the city in neighbourhood planning

The 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan has been built within the Lefebvrian perspective of the right to the city, as in works by Purcell (Citation2002, Citation2013), Mitchell (Citation2003), Souza (Citation2010) and Harvey (Citation2012). In this perspective, we understand the right to the city as the right to appropriate urban spaces, not only in the sense of being able to access and use all of the different spaces and services that the city can offer, but also, and more importantly, in the sense of being actively involved in the production the city – by having the freedom to reinvent ourselves and the city (Harvey Citation2012). Thus, ‘right’ is understood here as a collective right that goes beyond institutional and national legality, favouring non-capitalist forms of socio-spatial interactions and prioritising the use-value (instead of the exchange-value) of space to enhance all aspects of human life in the city.

Although agreeing with Lefebvre on the need to gain autonomy towards the State through innovative forms of self-management, we are aware that these practices can serve the interest of the neoliberal state as the responsibility to provide basic public-interest policies, programs and services is increasingly put into the hands of unpaid ‘voluntary’ citizens (Jessop Citation2002; Roy Citation2005).

Neighbourhood plans as organising tools for local demands and vindications on public authority have resulted – mainly – in urban plansFootnote14 that aim to overcome precarious urban and space-regulation conditions. Consequently, such plans contribute to substantiating the claims – and the process itself of participating in decision-making as regards the fate of our cities, albeit this participation still requires intercession on the part of the State, and thus cannot reach the autonomy and self-governance advocated by Lefebvre (Citation2001) and Souza (Citation2010). In fact, the vast majority of inhabitants of Latin American countries are still in need of basic services and infrastructure to be provided or improved (basic sanitation systems and networks, other utilities and well-located, quality housing). The level of instability in our cities still forces us to organise our more urgent claims and submit them to public administrators, who bear the responsibility of providing these constitutional rights.

Purcell (Citation2002, Citation2013) makes a provocative and quite relevant observation for a revised right to the city, noting that US levels of urban blight are largely lower than Latin America’s. In the Brazilian experience, as well as in the 2 de Julho Plan, a whole set of urgent needs are still related to ensuring survival conditions and access to basic social rights, or to the possibility itself for residents to remain in the city centre. These come as a priority and are largely mediated by the State, at the expense of more autonomous and self-managed radical actions.

Dealing with such a state of affairs, to be overcome in an extremely unequal society filled with such immediate and pressing needs does not mean abandoning the utopian horizons raised by the Lefebvrian perspective. That is why, in urban reform, effective commitment to a strategy for establishing the right to the city should have a revolutionary character. As stated by Henri Lefebvre:

From issues regarding land ownership to segregation, each urban renovation project calls into question not only the structures of the existing society and daily (individual) relationships, but also those intended to be forcefully and institutionally imposed on what remains of the existing urban reality. Reformist by nature, an urban-reform strategy “necessarily” becomes revolutionary, not by the force of things, but by being against what has been established. (Lefebvre Citation2001, p. 113, our emphasis)

With regard to the effective participation of local residents and organisations in the Neighbourhood Planning activities, especially as to the representation of the different social groups existing in the neighbourhood, we understand that popular participation is a long-term process that does not merely depend on the efforts invested by an organizing team – but also reflects both historical and circumstantial sociopolitical, cultural and economic processes. These processes are conditioned and structured by unequal power relations that need to be acknowledged, made explicit and faced as an inescapable part of the participatory process. Although these power dynamics cannot be ignored, they certainly can be openly contested by a participatory conflict-based planning process, in ways that can begin to subvert or reconfigure them . This approach stands in sharp contrast to the institutionalised planning strategies like those headed by the State. Their pro-form and liberal logic built upon an a-priori concept of equality create an illusionary democratic context that only helps to invisibilise – and thus perpetuate – existing social asymmetries.

Therefore, we contend that the most intense debates occurring in the elaboration of a Neighbourhood Plan also strengthen the right to the city, as they arise at the local level – where the processes, relationships and interests of groups operating at various levels converge, intersect and collide. As we have argued, the most socially and politically significant issues are put under the spotlight precisely in the midst of conflicts, and whenever counter positions are expressed – thus serving as guidelines for proposals that can (re)define the course of urban development, towards more socially just and emancipatory goals.

The neighbourhood plan can serve as an urban planning tool that takes the right to the city closer to being accomplished, with the goal of reversing State practices that (re)produce socio-spatial inequalities and socio-environmental injustices. It can be used as an instrument for making the State more accountable, challenging the neoliberal logic and reinstating government bodies’ role in providing the social welfare policies and services they have responsibility over. This notably concerns City Administration, as the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 determines as the responsibility of these federal entities ‘to design and deliver, directly or by concession or permission, the public services of local interest’ (art. 30, item V), a legal right obtained through decades of social struggles.

Convincing the municipal government to embrace the neighbourhood plan as a legitimate tool of demands and even urban planning is yet another challenge that residents and neighbourhood social organisations will have to face. In this sense, two fronts are possible. One is using the neighbourhood plan as a claiming tool. The collective work of organisation and qualification of the demands of local residents gives the neighbourhood plan the status of a powerful tool for asserting claims and rights before the municipal and state governments. The second front is an inclusion of the neighbourhood plan within the formal planning system of the municipal administration. The Municipal Master Plan of Salvador recognises the neighbourhood plan as part of the formal municipal urban planning system, but for this, it needs to be submitted and approved by its planning body.

During the elaboration of the neighbourhood plan, we were able to accompany some difficulties in the relationship of residents and organisations with the municipal and state governments, as well as important achievements. In the case of the expropriation process where residents claim the right to transparency and public participation in neighbourhood reforms, the tensions between the community and State representatives were visible. Answers to these claims, when they came, were often evasive and never conclusive. In terms of achievements, after intense participation of the residents in public discussions for the preparation of the Municipal Master Plan in 2016, a demarcation was conquered as a Zone of Special Social Interest (ZEIS), in the Vila Coração de Maria, which is part of the neighbourhood. This achievement, within the field of municipal urban planning, formalised the right of residence for the inhabitants of Vila Coração de Maria in the face of eviction threats by the property owner. These facts, even though they do not equate to the enforcement of the corresponding social and collective rights, may help give visibility to groups of historically marginalized inhabitants, and to difficult, at least in some levels, the absolute dominion of hegemonic agents, besides keeping open horizons of experimental utopia, in the perspective raised by Lefebvre (Citation2001).

It is important to emphasise, however, that the neighbourhood plan does not only constitute an instrument to stake claims to governments, but its results and propositions also include the residents and the neighbourhood social and cultural organisations as their implementation agents. There are some propositions within the Plan, which, to be implemented, only require actions from residents and social organisations, as in the case of the creation of a cultural and artistic circuit in the neighbourhood. There are also propositions that involve partnerships with governments and also with private agents, like neighbourhood merchants and funding agencies, public and private.

In this way, we see that the neighbourhood plan exists and functions as a tool for social organisation and demands, be it in the organisation and qualification of the demands to entities of the public administration or the organisation of collective actions to be engendered by the neighbourhood residents themselves. With this, residents reaffirm the responsibilities of governments in neighbourhood improvement actions, and go beyond, organising their own actions towards the construction of autonomy and self-management, important notions to carry along, on the road to the right to the city (Lefebvre Citation2001; Purcell Citation2002, Citation2013).

The experience of 2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan also leads us to think about the role of the university in the planning process and in the construction of alternative representations of space. This question refers to the problematisation of the generally neglected extension, in the face of a higher valuation of research by ‘productivity’ indicators within the neoliberal university. In counterposition to this logic, the extensionist can activate places of experimental and shared knowledge production involving university agents and groups of inhabitants without losing its inherent articulation with teaching and research. It is now possible to identify different experiences in progress involving Brazilian university research and extension groups, collectives, activists and urban social movements (e.g. Lugar Comum, Práxis, Indisciplinar). These collaborative experiences are oriented, explicitly or not, by the notion of inter-knowledge (Santos Citation2007).

Of course, we cannot ignore the conflicts between common and specialised knowledge that lie in this kind of shared knowledge production. However, despite the challenges of inter-knowledge, we recognise the importance of extensionist experiences that have been dedicated, amongst other things, to the elaboration of collective instruments and practices that seek to strengthen and respond to the demands of inhabitants in situations of violation of social rights, in contexts of struggles and urban conflicts. In a recurrent way, urban public administration practices are closed to citizens’ deliberation, either by an explicitly authoritarian conduction or the simulacra of institutional participation. In view of this closure, the creation of experimental and collective places of inter-knowledge, of which the university participates, can play a relevant role in the construction of alternative representations of space, (re)opening other possibilities of public action in the city by way of radical/subversive/transgressive planning. From this perspective, the right to the city is understood in its most radical form, as social, economic and political urban restructuring, seeking to transfer the power to produce the city into the hands of its inhabitants – and increasingly out of those few who represent the interests of capital.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The process of gentrification in the 2 de Julho neighbourhood was analysed through a survey on real-estate appreciation in property transfer transactions and new real-estate development advertisements in the media.

2. The MNB2J was formed in June of 2012 when residents of the 2 de Julho neighbourhood initiated actions to counter the ‘Santa Tereza Neighbourhood Humanisation Project’. The Movement’s main objective is to defend the right to the city within and beyond the neighbourhood by contesting urban practices that reproduce social inequalities and injustices.

3. The regulation and institutional norms of Brazilian public universities made a critical, epistemological and conceptual revision of the University’s role as an articulated set of social functions. In the mid-twentieth century, social commitment, as an essential function of the University, takes shape through the concept of extension, which would complete the indissociable trinomial of teaching-research-extension. Today, extension is interpreted as an educational praxis in a multi-referenced and intercultural world (UFBA Citation2010).

4. Although the recently passed Administrative Restructuring Law requires District Administrations to be established in Salvador, laying out the regional subdivision – as per the City Executive Note No 23/12, sent to the City Council in December 2012.

5. This outline takes the following streets and reference points as the boundaries of the 2 de Julho neighbourhood: Lafayette Coutinho Avenue (Western Limit), Preguiça Hill (Northern Limit), Carlos Gomes Avenue (Eastern Limit), and Aflitos Square (Southern Limit).

6. We took as a reference the definition given by Federal Decree No 6,135/2007, which provides for the Federal Government Unified Registry for Social Programs. This decree defines low-income population as the dwellers of households with an overall monthly income of up to three times the minimum wage.

7. In 2015, the expropriation decrees of the State Government were amended by Decrees 16,354 / 2015 and 16,386 / 2015, eliminating overlaps with current Municipal Decree in the same area.

8. City officials presented all the content of the studies and the plan – covering a wide range of diverse topics – in a one-off public hearing, thus precluding real content understanding by the ‘participants’.

9. The extension project for financing the plan was prepared, submitted to the Ministry of Education and approved in 2013, but implementation activities only started the following year.

10. These municipal projects have included the restoration of the neighbourhood traditional market, which, despite some improvements (bathrooms and less precarious conditions for the venders who were granted access to permanent booths) has been criticised by residents and merchants for being poorly designed, making access to the products more difficult and a space less amenable to fluid interactions between people.

11. The Articulation of Movements and Communities of Salvador’s Old Centre (Articulação dos Movimentos e Comunidades do Centro Antigo de Salvador) was founded in 2014. This ‘Articulation’ includes: the Movement ‘Our Neighbourhood is 2 de Julho’ (Movimento Nosso Bairro é 2 de Julho_MNB2J), Bahia’s Homeless Movement (Movimento dos Sem-Teto da Bahia_MSTB), the Community of Gamboa de Baixo, the Community of Preguiça, and the artisans of Ladeira da Conceição da Praia. It also counts with the assistance of two social movements’ advising entities: the Institute for the development of Social Actions (Instituto de Desenvolvimento em Ações Sociais_IDEAS) and the Study Centre for Social Action (Centro de Estudos em Ação Social_CEAS).

12. The 10 themes were: education and health; combating inequality and social exclusion; mobility and transport; infrastructure, sanitation and the environment; housing; public security; culture and arts; leisure and sports; public and green spaces; and, heritage preservation.

13. A total of 83 properties within the neighbourhood were categorised as ‘urban voids’ (unused properties), most of which being in state of ruins. Another 53 were categorised as underutilised properties.

14. Based on studies of Salvador Neighbourhood plans that were carried out in Salvador since the 2000s include: Nova Constituinte São Marcos, Mussurunga, Baixa Fria and Baixa de Santa Rita Plans – led by the municipality –, and the Saramandaia Plan, led by FA-UFBA in partnership with neighbourhood residents.

References

- Arantes O. 2000. Uma estratégia fatal: a cultura nas novas gestões urbanas. [A fatal strategy: culture in new urban management]. In: Arantes O, Maricato E, Vainer CB, editors. A cidade do pensamento único: desmanchando consensos [The unified-thought city: dismantling consensus]. Petrópolis (RJ): Vozes; p. 11–73.

- Bahia. 2013a. Decree nº 14,865/2013. Declara de utilidade pública, para fins de desapropriação, imóveis no Centro Antigo de Salvador [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Apr 16]. Available from: http://www.legislabahia.ba.gov.br/index.php

- Bahia. 2013b. Decree nº 14,868/2013. Declara de utilidade pública, para fins de desapropriação, imóveis no Centro Antigo de Salvador [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Apr 16]. Available from: http://www.legislabahia.ba.gov.br/index.php

- Brasil. 2001. Federal Law nº 10,257/2001. Cria o Estatuto da Cidade, Regulamenta os arts. 182 e 183 da Constituição Federal e estabelece diretrizes gerais da política urbana [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Apr 16]. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/LEIS_2001/L10257.htm

- Calderon C. 2013. Politicising participation: towards a new theoretical approach to participation in the planning and design of public spaces [dissertation]. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Carlos AFA. 2004. O espaço urbano: novos escritos sobre a cidade. [Urban space: new writings on the city]. São Paulo: Contexto.

- Escritório de Referência do Centro Antigo de Salvador (ERCAS), UNESCO. 2010. Centro Antigo de Salvador: plano de reabilitação participativo [Salvador’s Old Centre: participatory rehabilitation planning]. Salvador (BA): Secretary of Culture, Pedro Calmon’s Fundation. Available from: http://www.centroantigo.ba.gov.br/arquivos/File/PlanoReabSSA.pdf.

- Fernandes A. 2013. Plano de Bairro 2 de Julho [2 de Julho Neighbourhood Plan]. Extension project submitted to PROEXT 2014. Salvador (BA): Faculdade de Arquitetura, UFBA.

- Fernandes A, Mourad LN, Silva HMB. 2016. La política urbana en las ciudades brasileiras: gentrificando los centros? [The urban politics in the brasilian cities: gentrifying the centres?]. In: Contreras Y, Lulle T, Figuerosa O, Editors. Cambios socioespaciales en las ciudades latinoamericanas: procesos de gentrificación? [Sociospatial changes in Latinamerican cities: processes of gentrification?]. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Bogota: Universidad Externado de Colombia; Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Faculdad de Arq; p. 389–422.

- Hall P. 2007. Cidades do amanhã: uma história intelectual do planejamento e do projeto urbanos no século XX [Cities of tomorrow: an intellectual history of urban planning and designing in the 20th century]. São Paulo: Perspectiva.

- Hamnett C 1991. The blind men and the elephant: the explanation of gentrification. Trans Inst Br Geogr. 16:173–189.

- Harvey D. 2012. Rebel cities: from the right to the city to the urban revolution. London (New York): Verso Books.

- [IBGE] Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatítica [Internet]. 2010. Census. Brasília: Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão. [accessed 2015 Mar 25]. Available from: http://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/

- Jessop B. 2002. Liberalism, neoliberalism and urban governance: a state-theoretical perspective. Antipode. 34:452–472.

- Jones P, Evans J. 2012. Rescue geography: place making, affect and regeneration. Urban studies. 49.11: 2315-2330.

- José BK. 2007. Políticas culturais e negócios urbanos: a instrumentalização da cultura na revalorização do centro de São Paulo (1975-2000) [Cultural policies and urban businesses: culture’s instrumentalisation in the upgrading of São Paulo’s centre (1975-2000)]. São Paulo: Annablume/Fapesp.

- Lefebvre H. 2001. O direito à cidade [The right to the city]. São Paulo: Centauro.

- Maricato E. 2002 Oct 3. Dimensões da tragédia urbana [Dimensions of the urban tragedy]. Comciencia [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Mar 25]. Available from: http://comciencia.br/dossies-1-2/reportagens/cidades/cid18.htm

- Maricato E. 2011. Brasil, cidades: alternativas para a crise urbana [Brazil, cities: alternatives for the urban crisis]. 5th ed. Petrópolis (RJ): Vozes.

- Mitchell D. 2003. The right to the city: social justice and the fight for public space. New York (London): Guilford Press.

- Mouffe C. 2000. The democratic paradox. New York: Verso.

- Mourad LN 2011. O processo de gentrificação do Centro Antigo de Salvador (2000 a 2010) [Salvador’s Old Centre gentrification process (2000-2010)] [dissertation]. Salvador (BA): Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA).

- Mourad LN, Figueiredo GC, Baltrusis N. 2014. Gentrificação no Bairro 2 de Julho, em Salvador: modos, formas e conteúdos [Gentrification of 2 de Julho Neighbourhood in Salvador: modalities, forms and contents]. Cadernos Metrópole. 16:437–460.

- Purcell M. 2002. Excavating Lefebvre: the right to the city and its urban politics of the inhabitant. GeoJournal. 58:99–108.

- Purcell M. 2013. The right to the city: the struggle for democracy in the urban public realm. Policy & Politics. 41:311–327.

- Rolnik R 2006. Por um novo lugar para os velhos centros [For a new place for the old centres]. São Paulo: Vitruvius, Minha Cidade [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/minhacidade/06.071/1945

- Rolnik R. 2011. Democracy on the edge: limits and possibilities in the implementation of an urban reform agenda in Brazil. Int J Urban Reg Res. 35:239–255.

- Roy A. 2005. Urban informality: toward an epistemology of planning. J Am Plann Assoc. 71:147–158.

- Salvador. 2013. Decree nº 24,435/2013 Declara de utilidade pública, para fins de desapropriação, imóveis no Centro Antigo de Salvador [Declares of public utility, for matters of expropriation, real estate in the old centre of Salvador]. Salvador (BA): Prefeitura Municipal de Salvador [Internet]. [ accessed 2015 Apr 14]. Available from: https://leismunicipais.com.br/a2/ba/s/salvador/decreto/2013/2444/24435/decreto-n-24435-2013-declara-de-utilidade-publica-para-fins-de-desapropriacao-os-imoveis-que-indica-e-da-outras-providencias?q=24435

- Salvador. 1983. Law nº 3.289/1983 Dispõe sobre as Áreas de Proteção Cultural e, Paisagística de Salvador [Dispose on the cultural and landscape protection areas of Salvador] Salvador (BA): prefeitura Municipal de Salvador [Internet]. [ accessed 2015 Apr 14]. Available from: https://leismunicipais.com.br/a2/ba/s/salvador/lei-ordinaria/1983/329/3289/lei-ordinaria-n-3289-1983-altera-e-da-nova-redacao-a-dispositivos-da-lei-n-2403-de-23-de-agosto-de-1972-e-da-outras-providencias?q=3289.

- Salvador. 2008. Law nº 7.400/2008 Dispõe sobre o Plano Diretor de Desenvolvimento Urbano (PDDU) do Município do Salvador [Dispose on the Master Plan of urban development of the municipality of Salvador]. Salvador (BA): Prefeitura Municipal de Salvador [Internet]. [ accessed 2015 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.gestaopublica.salvador.ba.gov.br/leis_estruturas_organizacionais/documentos/Lei%207.400-08.pdf.

- Santos BS. 2007. Para além do Pensamento Abissal: das linhas globais a uma ecologia de saberes [Beyond Abyssal Thinking: from global lines to an ecology of knowledges]. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 78: 3-46.

- Santos M. 2008. A Natureza do Espaço: técnica e Tempo, Razão e Emoção [The nature of space: technique and time, reason and emotion]. 4th ed. São Paulo: EDUSP.

- Serpa A, editor. 2007. Cidade popular: trama de relações socioespaciais [The popular city: interweaving socio-spatial relations]. Salvador (BA): EDUFBA.

- Slater T. 2006. The eviction of critical perspectives from gentrification research. Int J Urban Reg Res. 30:737–757.

- Smith N. 1987. Gentrification and the Rent Gap. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 77:462–465.

- Soja E. 1989. Postmodern geographies: the reassertion of space in critical social theory. New York: Verso.

- Souza ML. 2010. Which right to which city? In defense of political-strategic clarity. Interface. 2:315–333.

- Swyngedouw E. 2004. Globalisation or ‘glocalisation’? Networks, territories and rescaling. Camb Rev Int Aff. 17:25–48.

- Thrift N. 2007. Non-representational theory: space, politics, affect. London: Routledge.

- [UFBA] Universidade Federal da Bahia. 2010. Estatuto & Regimento Geral [Statute and general regulation]. Salvador (BA) [Internet]. [accessed 2017 Sept 02]. Available from: https://www.ufba.br/sites/devportal.ufba.br/files/Estatuto_Regimento_UFBA_0.pdf

- Vainer CB. 2002. Pátria, empresa e mercadoria: notas sobre a estratégia discursiva do planejamento estratégico urbano [Nation, enterprise and merchandise: note on the discursive strategy of the urban strategic planning]. In: Arantes O, Maricato E, Vainer CB, editors. A cidade do pensamento único: desmanchando consensos [The unified-thought city: dismantling consensus]. Petrópolis (RJ): Vozes; p. 75–104.

- Vainer CB, Bienenstein R, Tanaka GMM, Oliveira FL, Lobino C. 2013. O Plano Popular da Vila Autódromo: uma experiência de planejamento conflitual. [Vila Autódromo Popular Plan: a conflictual planning experience]. Paper presented at: XV ENANPUR Conference, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife.

- Villaça F. 2005. As ilusões do Plano Diretor [The illusions of the municipal urban plan] [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Apr 15]. “publisher unknown” [place unknown]. Available from: http://www.flaviovillaca.arq.br/pdf/ilusao_pd.pdf.

- Watson V. 2003. Gender and political interests: taking institutions seriously. Paper presented at: TASA 2003 Conference; University of New England, Armidale.