ABSTRACT

After the Paris Agreement that put stronger emphasis on the development of climate change adaptation policies and on the definition of financing mechanisms, there is a patent need to track whether actual planning efforts are proving sufficient. This entails the development of assessment methods and metrics as plans are drafted and actions implemented. To this end, this paper explores the concept of credibility as a critical issue in climate policy and develops an Adaptation Policy Credibility (APC) conceptual and operational assessment framework for helping to allocate public funding and private investments, and for implementing and catalysing climate policy. Through a pilot testing in four early-adopting cities (Copenhagen, Durban, Quito and Vancouver), a clear potential for large-n tracking and assessment exercises of local climate adaptation plans is envisaged. The APC approach might also be useful to guide individual cities that aim to improve their adaptation planning and policy-making processes.

Introduction

Planning for adaptation to climate change has emerged as a central component of climate policy over the last decade (Moss et al. Citation2013; Preston et al. Citation2015). The Paris Agreement set an ambitious pathway for adaptation that urges nations, regions and cities to act on climate change impacts together with other public and private stakeholders (Lesnikowski et al. Citation2017).

As interest in adaptation increases―including investment in adaptation policies, programmes, and actions―there is a need to track whether these are effective in reducing vulnerability and building resilience (Bours et al. Citation2015; Ford et al. Citation2015; Haasnoot et al. Citation2018). This requires new methods, tools and frameworks to measure the actual progress on adaptation (Ford et al. Citation2015; Chen et al. Citation2016; Magnan Citation2016; Magnan and Ribera Citation2016). An ability to track adaptation progress is highly relevant for governments at different scales looking to prioritise their investments to effectively adapt and to define how to access climate adaptation funding, especially in developing countries (Araos et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Ford and Berrang-Ford Citation2015; Lwasa Citation2015; Sud et al. Citation2015). Likewise, it is fundamental to reduce policy uncertainties and provide the right guidance to the private sector, such as robust criteria to define their funding strategies (Tribbia and Moser Citation2008).

Efforts made to date, however, are far from being comparable to those tracking mitigation progress, and have a number of weaknesses, including the lack of consistent definitions and practices, agreed metrics, comparable baselines, standardised approaches to data collection and robust guidance (JoAnn Carmin et al. Citation2012; Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013; Reckien et al. Citation2014; Ford et al. Citation2015; Araos et al. Citation2016; Heidrich et al. Citation2016; Magnan Citation2016; Biesbroek et al. Citation2018). In current adaptation tracking practice, the existence and nature of climate change adaptation policiesFootnote1 has been used as an indicator of progress. Relevant studies have documented, examined and compared adaptation policies at national (Berrang-Ford et al. Citation2014; Austin et al. Citation2016; Lesnikowski et al. Citation2016; Pietrapertosa et al. Citation2017), city (Olazabal et al. Citation2014; Araos et al. Citation2016; Woodruff and Stults Citation2016; Reckien et al. Citation2018) and community scales (Pearce et al. Citation2011).

Nevertheless, the development of policies on its own, while indicative of adaptation policy progress, may not actually lead to vulnerability or risk reduction. There is evidence, for instance, that local authorities have often used climate mitigation policies to recodify existing strategies without having substantial impact on emissions reduction (Millard-Ball Citation2013). In the context of climate adaptation strategies, an ambiguous use of the concept of adaptation in policy making may also end in a general lack of concrete measures and implementation (Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013).

This paper presents a conceptual framework to assess the credibility of climate change adaptation policies, a metrics-based assessment model at the local scale, and a pilot test of the model in four cities: Copenhagen (Denmark), Durban (South Africa), Quito (Ecuador) and Vancouver (Canada). The credibility of climate adaptation policies is here defined as the likelihood that such policies will be effective in reducing or avoiding the impacts of climate change and sustained in the long-term or, at least, for the term for which they have been originally defined by responsible parties. The pilot test is used to draw conclusions on the usability of the framework and the potential and interest of a large-n experiment.

The paper is structured as follows: the next section explains the methods and data used. This is followed by a review of the main literature describing the concept of credibility in climate adaptation policy making and influencing factors. Based on this, a conceptual approach for assessing the credibility is developed and operationalised for local adaptation policies. Subsequently, the results from a pilot application of the approach in the aforementioned cities are presented. The paper finishes by reflecting on the proposed framework and its potential application.

Data and methods

The Adaptation Policy Credibility (APC) framework is developed based on a review of the literature identifying key aspects of climate adaptation planning process. The review is summarised in the next section. Likewise, indicators and metrics used to operationalise the conceptual framework have been chosen based on a review of the literature relevant to each of the components of the conceptual framework.

As the APC is aimed to be applied in large-n experiments, metrics need to be evaluated. In this paper, scoring is proposed for evaluation and comparison purposes because it is an easy-to-apply method that allows the creation of a composite credibility index (see, e.g. Preston et al. Citation2011; Heidrich et al. Citation2013; Araos et al. Citation2016; Lesnikowski et al. Citation2016; Woodruff and Stults Citation2016). Combining metrics might be challenging when it comes to adaptation assessment due to a lack of knowledge about the complex interactions between the components assessed (Ford and King Citation2015). Arguably, a composite index can here be considered a first step towards the recognition of the need to compare contexts and transfer knowledge across policies and, in this case, cities.

The conceptual and operational framework is tested using a set of local adaptation policies in four cities: Copenhagen, Durban, Quito and Vancouver. These cities have been selected because they provide examples from both developing and developed countries and they are internationally recognised for their early action on adaptation and, therefore, their efforts are well documented.

The adaptation policies are analysed as stand-alone documents motivated by the need to protect urban populations, infrastructures and other urban assets from current climate change impacts and to build adaptive capacity for future impacts. In building this framework, two choices for data collection were considered: (1) self-reporting (by city officials) based on policy documents and self-knowledge on the policy processes of the city (see, e.g. Campos et al. Citation2017) or (2) a systematic review process by expert analysts (see, e.g. Araos et al. Citation2016; Reckien et al. Citation2018). Although a self-reported assessment could lead to context-specific and detailed data of non-publicly available information, a systematic review process offers objective and comparable data on released and publicly available information, features that, according to these authors, provide more reliability to public policies. For this reason, the second option was chosen and a systematic review process for the selected cities was performed: each city’s municipal website was identified and scanned for climate change adaptation planning documents.

Finally, in the pilot test, the scoring procedure merits mention because of its influence on the reliability of the outcomes (Lyles and Stevens Citation2014). To provide a higher level of objectivity, all metrics have been coded independently by two different analysts with expertise in climate adaptation policy document analysis. The two analysts have compared scores, identified elements of disagreement and reconciled scores based on the new information considered. After this process, no conflicting scores have been found. Details on the scoring procedure and evaluation process of each of the defined metrics are included in the subsection ‘Operational framework at a local scale’, as part of the methodological development of this paper.

Credibility in adaptation policy making: a review

The concept of credibility in climate policy

For a piece of information to be credible, it should be able to ‘be believed in, justifying confidence’ (OED Citation2013). Credibility is a concept widely used in the policy sciences (see Drazen and Masson Citation1994), mainly referring to problems related to regulatory policies (Helm et al. Citation2003). Specifically, a large body of literature dealing with credibility is framed in the development of monetary policies (see, e.g. GomezPuig and Montalvo Citation1997). This literature illustrates that the credibility of a plan or policy depends not only on the plan or policy itself, but also on the context and conditions in which it is developed and implemented and on the motivations and incentives of the authorities responsible (North Citation1993; Drazen and Masson Citation1994; Helm et al. Citation2003). For example, Helm et al. (Citation2003) argued that the UK’s carbon policy was not credible because it relied on the price of technology being low and decreasing over time. This involves a credibility problem around the ‘time inconsistency’ of the decision-making sequence where private-sector agents make irreversible decisions before policy makers act.

Credibility has been recognised to be an important issue in environmental and climate policy, primarily in the context of the role of science and experts in delivering ‘usable knowledge’ (Anderegg et al. Citation2010; Lemos et al. Citation2012; Ford et al. Citation2013b; Heink et al. Citation2015) but also in relation to regulations (Helm et al. Citation2003) or commitments (Averchenkova and Bassi Citation2016). With exceptions (e.g. Averchenkova and Bassi Citation2016 concerning the mitigation commitments under the Paris Agreement), empirical studies dealing with credibility (or any similar attribute) in the context of climate policy are scarce, especially regarding adaptation (Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013). Averchenkova and Bassi (Citation2016) state that credibility is essential to generate the necessary flow of climate finance from private and public sectors, at different levels of governance (national, regional and local). Credibility in the context of mitigation, they maintain, ‘is vital for building trust among negotiating parties, as this will help to increase the ambition of pledges over time’ (p. 39). They identify four key determinants for policy credibility: coherent and transparent rules and procedures, dedicated and supportive players and organisations, history of norms and public opinion, and past performance.

The concept of ‘policy credibility’, as seen in the work of Averchenkova and Bassi (Citation2016), has not been developed in and adapted to the context of adaptation. This may reflect adaptation not yet being paid sufficient attention in public negotiations across scales, due to it being less clearly recognised as a global public good, and hence the goal of building trust not yet being given much weight (Magnan Citation2016). Nevertheless, given the need to inform policy making, investment, and funding strategies on adaptation, and the reliance of many adaptation tracking studies on the (in)existence of adaptation policies and plans to measure adaptation progress, developing an approach to assess credibility seems an important research step in the adaptation tracking field.

Factors influencing credibility in current adaptation planning literature

Diverse approaches have been proposed in the literature to assess the abilities that a system may (or may not) have to plan for adaptation or the factors that may prevent adaptation action. The assessment of adaptive capacity (Engle Citation2011), for example, provides information on which factors help to build capacity to face future climate impacts. This information is key to assess whether the system has sufficient resources to adapt in terms of institutional structure, knowledge on management systems, infrastructure and technology, past experience, etc.

Other approaches focus on the assessment of barriers to adaptation, which are critical to identify potential deviations in the adaptation process. Barriers to adaptation have been theoretically discussed (Adger et al. Citation2009; Moser and Ekstrom Citation2010; Biesbroek et al. Citation2013; Ford and King Citation2015; Huitema et al. Citation2016), and empirically examined (Measham et al. Citation2011; see, e.g. Bierbaum et al. Citation2012; Reckien et al. Citation2015; Tilleard and Ford Citation2016; Nordgren et al. Citation2016). Barriers may include: lack of knowledge, uncertainty about impacts, the extended time periods involved, lack of leadership, lack of financial resources, institutional constraints (e.g. rigidity, lack of competencies), limited stakeholder engagement and participation, poor decision-making culture (not iterative or flexible), lack of public support, divergent risk perceptions and cultural attachments. Based on these findings, credible climate change adaptation policies should inspire confidence to overcome social, technical, economic and political adaptation barriers, and thereby engage better with stakeholders (e.g. funding agents, private investors) for effective action. In this sense, legitimacy has been identified as an important pillar of (perceived) successful adaptation (Adger et al. Citation2005), and refers to the consideration of equity and justice in policy-making and scientific processes. It includes the engagement of stakeholders and civil society in the development of the plan and the transparency of processes and information.

The assessment of adaptive capacities and barriers to adaptation both require consideration of the factors that enable or prevent current or future adaptive processes; however, these approaches do not provide information on how such processes should be built. Building on this gap, the concept of adaptation readiness was proposed to examine the adaptation process by considering what is actually being done to prepare for adaptation (Ford and King Citation2015; Tilleard and Ford Citation2016).

Other approaches related to plan evaluation have been proposed to assess how well a plan is aligned with adaptation outputs and outcomes. For example, Preston et al. (Citation2011) argued that plan evaluation provides transparency and formal definitions of criteria and methods that can be useful for accountability in an evidence-based policy context. As part of plan evaluation research, a number of recent studies have assessed the quality of climate change mitigation and adaptation plans at the local level (Baynham and Stevens Citation2014; Woodruff and Stults Citation2016). Plan quality assessments are generally performed in order to identify aspects of plans that are considered important to achieve the objectives pursued as well as aspects that should be improved (Stevens Citation2013). They are more detailed than other approaches (e.g. Preston et al. Citation2011) and allow plans to be compared across domains (Woodruff and Stults Citation2016). Baynham and Stevens (Citation2014) argued however, that the hypothesis that plan quality standards correlated with a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and better preparedness for climate change impacts had not been evidenced so far and proved more complex for adaptation than for mitigation. Plan quality assessment should therefore not be the only aspect on which the concept of credibility relies.

In fact, as a result of the long-term nature of many adaptation strategies, the problem of credibility in adaptation policy is also tightly linked to whether a policy is intentional and substantial (Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013); that is, to whether climate change impacts originated the need for policy development and to the level of contribution of such policy to problem resolution. Nevertheless, it may be difficult to establish valid methods for measuring the outcomes of adaptation policies in a similar way to that used for mitigation policies (see, e.g. Millard-Ball Citation2012) as many of the impacts of climate change will be felt in the long term and therefore are not easy to measure or estimate (Ford et al. Citation2013a). Consequently, a focus on measuring process aspects of adaptation policy has emerged to facilitate tracking exercises (Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013).

Development of an APC framework

Conceptual framework

Building upon the review of approaches set out in the previous section, herein, the main aspects of credibility are identified and an APC framework is proposed based on: policy credibility, as defined by Averchenkova and Bassi (Citation2016), plan evaluation (as in e.g. Preston et al. Citation2011; Baynham and Stevens Citation2014), adaptive capacity and readiness (as in Ford and King Citation2015), whether the plan is intentional and substantial (as in Dupuis and Biesbroek Citation2013) and the legitimacy of the process (as in Adger et al. Citation2005). A framework to assess APC should therefore look at the institutional and policy context in which the policy was developed, the resources dedicated to its creation and maintenance, the knowledge used for the decision-making process and the level of engagement with the stakeholders and the public.

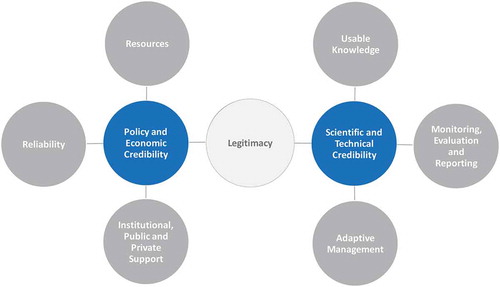

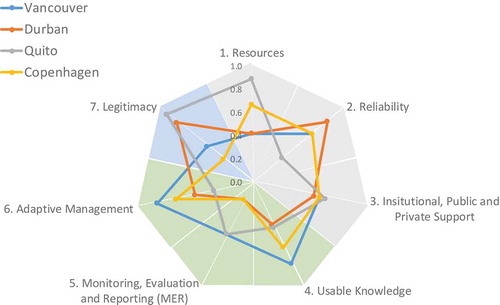

Herein, this study proposes a framework that links the aforementioned aspects around a structure of three major areas: Policy and Economic Credibility, Scientific and Technical Credibility, and Legitimacy, which is common to the first two (see ). Policy and Economic Credibility is divided into three components: Resources, Reliability, and Institutional, Public and Private Support. ‘Resources’ refer to the means required for the implementation of the plan and ‘Reliability’ to past performance and current assignment of human resources for plan definition, approval and implementation, while ‘Institutional, Public and Private Support’ refers to the passive or active engagement of diverse public and private actors in the development of the plan. Scientific and Technical Credibility is divided into three components: Usable Knowledge; Monitoring, Evaluation & Reporting (MER); and Adaptive Management. ‘Usable Knowledge’ refers to the production and use of contextualised evidence (regarding climate impacts, risks and vulnerability) according to local needs and ‘MER’ to the existence of systems that assess progress and outcomes according to a set of goals, while ‘Adaptive Management’ refers to the process of learning through readjustment processes that allows revision, redefinition or change to alternative pathways. Overall, therefore, the APC comprises seven components, including ‘Legitimacy’.

Operational framework at a local scale

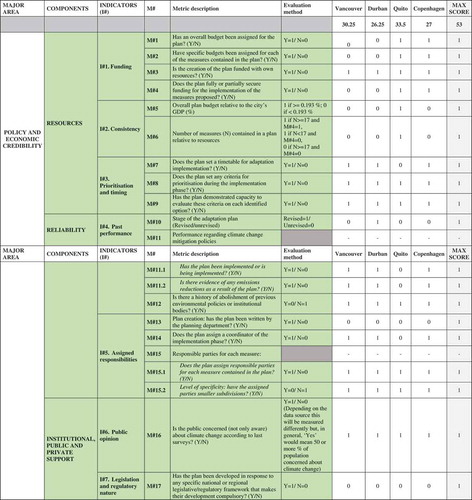

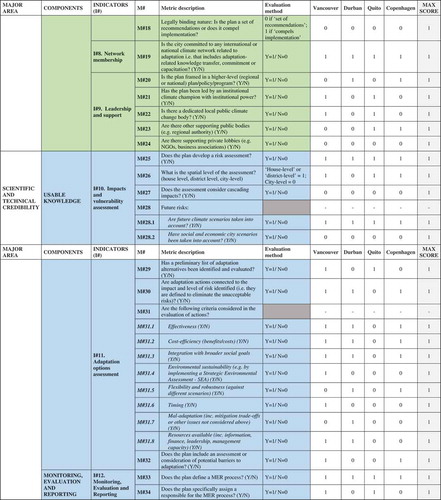

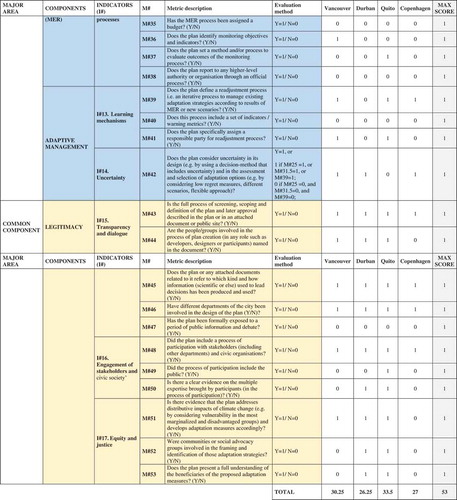

Local adaptation policies usually take the form of strategies or more concrete plans setting out a series of measures defined to reduce assessed or perceived climate risks. For the seven components identified in the conceptual framework (), a review of the relevant literature has been performed resulting in the identification of 17 indicators and 53 assessment metrics. lists the indicators selected and the number of metrics defined for each indicator. The complete list of metrics with an extended description and the chosen evaluation method for each metric can be found in the Appendix (Appendix 1, A1).

Table 1. Operational framework for the assessment of local adaptation policy credibility.

Most of the metrics are qualitative and are defined as closed questions (e.g. Yes or No) (see proposed evaluation method for each specific metric in A1). Positive responses reflect a contribution to the credibility of the policy, and are therefore awarded with 1 point, otherwise, 0 points. For a few open questions, (i.e. referring to plan budget, see metric M#5, or the number of measures contained in the plan, see metric M#6), a specific evaluation method that translates quantitative data into 1 or 0 has been defined.

A lack of information or clarity on the question under assessment either in documents or on the authority’s official websites is indicative of a low credibility; therefore, 0 points are given. Finally, to build the composite credibility index, the scores of the metrics across the indicators are summed up (sub-metrics will be equally weighted, e.g. M#11, M#15, M#28 and M#31). The maximum score for a plan, and therefore, the maximum credibility score, is equivalent to the total number of metrics, i.e. 53.

Pilot application: results and discussion

The framework has been tested using climate adaptation policies of 4 cities with population of over 1 million on different continents and representing different degrees of development, namely: Copenhagen, Durban, Quito and Vancouver. All the cities selected are internationally known for their action on adaptation and are recognized early adaptors; they all have adaptation plans approved between 2006 and 2012, meaning that the plans are all well documented and may even have been revised. Three of them were identified as extensive (Vancouver) or moderate (Quito and Durban) adaptors in the global assessment of urban adaptation by Araos et al. (Citation2016) (while Copenhagen was not in the sample, but has been identified elsewhere as an early adopter of climate policy). As early adaptors, they have made public commitments to adaptation and have joined and submitted their plans to international climate networks (such as the Compact of Mayors or C40). Their extensive experience in adaptation policy making suggested that data sources would be available for most if not all of the APC metrics. Policies related to either climate change in general (2 cases, Durban and Quito) or adaptation to climate change (2 cases, Vancouver and Copenhagen) were identified both containing adaptation measures. Detailed results including metrics and credibility index scores and all documents and their sources (city official websites) are included in the Appendices (A1 and A2 respectively).

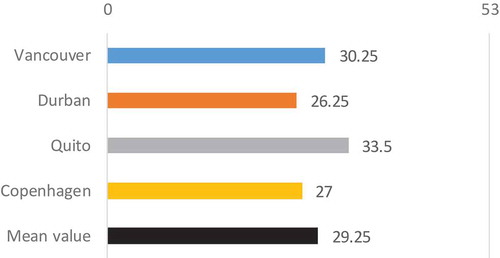

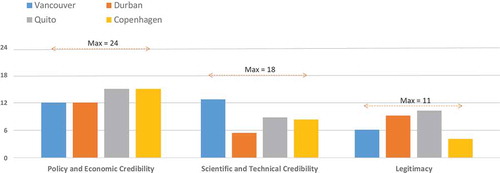

shows the final credibility index scores for each city. The best results were obtained for Quito, followed by Vancouver, Copenhagen and Durban. The average credibility index score for these four cities considered to be early and high or extensive adaptors is 29.25 (SD = 3.32) out of a total of 53. Even in the case of extensive adaptors, there are clear areas for improvement, though these may differ between the cities.

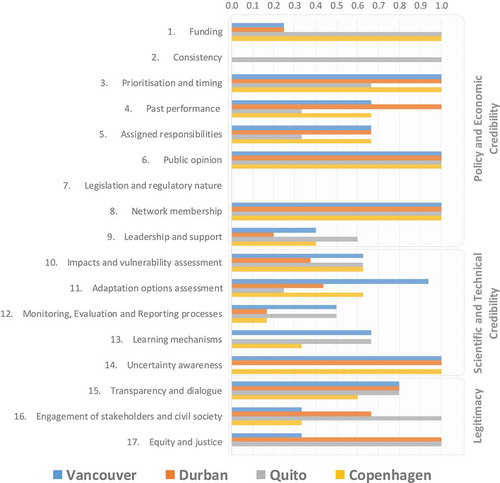

As the number of indicators and metrics is not balanced across areas or components (), areas for improvement need to be analysed individually (see ). Out of 24 points, Quito and Copenhagen score better in Policy and Economic Credibility (), which is mainly to do with the assignment of budgets (see for normalised scores for each indicator). Vancouver obtained the highest score in relation to Scientific and Technical Credibility (). This is probably a result of the use of the ICLEI adaptation methodology (ICLEI Citation2013) that has increased the credibility of its adaptation policy in terms of adaptation options assessment, the establishment of an MER process and their focus on learning mechanisms. Regarding legitimacy, Durban and Quito have more credible participatory processes in place that engage stakeholders and civil society and greater emphasis on vulnerable groups and equity (see and ).

Figure 3. Credibility scores by major area: Policy and Economic (over 24), Scientific and Technical (over 18) and Legitimacy (over 11).

Figure 4. Normalised credibility scores by indicator. Equal weights for metrics in each indicator have been considered (scores by metric can be found in A1).

Funding and consistency of planned actions with resources in the city are aspects that clearly need to be strengthened. These are two correlated indicators that provide one of the most important factors in terms of Policy and Economic Credibility. No budget assignment means no resources for implementation or no plan to acquire them. Further, in relation to Policy and Economic Credibility, developing regulatory frameworks can help instrumentalise climate adaptation in cities and mainstream it in current urban planning regulations. This would effectively channel efforts for implementation and attract public and private investments. Nevertheless, none of the cities have developed their plans in a regulatory framework or adopted legally binding measures. In terms of Scientific and Technical Credibility, as noted in earlier adaptation tracking studies (Araos et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Stults and Woodruff Citation2016; Woodruff and Stults Citation2016), MER systems are not widely implemented and learning mechanisms to enable adaptive management are not sufficiently credible (). Notably, credibility of adaptation policies based on their Legitimacy is stronger in developing (Durban and Quito) than in developed cities (Vancouver and Copenhagen) (see ). A preliminary hypothesis that requires further investigation is that this might be the result of a stronger culture of participation when governance structures are lacking. Although governance and democratic structures tend to be more formalised in developed countries, this does not necessarily mean that society’s interests are properly represented or fully understood by public decision makers, and hence, legitimacy processes are required to avoid unintended consequences or basing adaptation strategies on incomplete information.

Figure 5. Normalised credibility scores by component. Shaded areas define the three major areas: policy and economic credibility (grey), scientific and technical credibility (green) and legitimacy (blue). Equal weights for metrics and indicator have been considered (scores by metric can be found in A1).

In line with this, it is interesting to reflect on how the different scores of credibility may or may not be related to the different development contexts. One may conclude, for example, that many of the actions in Quito’s adaptation policy may be related to a development deficit. Sherman et al. (Citation2016) found that the literature on adaptation in developing countries on the ground offers different interpretations of the integration of adaptation and development. They recognise that this results in different considerations regarding adaptation design, implementation, funding, monitoring and evaluation (Sherman et al. Citation2016). In this pilot test, any effort puts into providing more adaptive capacity has been considered an indicator of adaptation progress and thereby provide credibility to the process. Further research is required to develop indicators of the relation between adaptation and development, the definition (e.g. how many actions are considered development) and rating (positive or negative) of which will depend on the approach taken (see Sherman et al. Citation2016).

Finally, it is important to note that the number of metrics considered in this assessment (53) requires an intensive effort in data collection and no analysis has been performed to study potential overlapping or the risk of double counting. From a methodological perspective, reducing the number of metrics would only be possible through a larger experiment (with a large-n sample) in which statistics offer critical information regarding the determinants of credibility.

Conclusions

The implementation of adaptation actions on the ground is largely in its early stages across national and local governments, and the information needed to verify their relative degrees of success will generally only emerge in the distant future, owing to the long-term nature of climate change (Araos et al. Citation2016; Lesnikowski et al. Citation2017). Moreover, the ability to attribute observed behavioural or ecological change to specific environmental policy outputs is contested in public policy literature (Knill et al. Citation2012). Consequently, adaptation policy studies focus primarily on either assessing the merits of various aspects of the policy process, or on tracking changes in policy outputs.

This paper explores the concept of credibility as a critical issue in climate adaptation policy and develops an APC framework that is based on a set of policy, economic and scientific criteria and on the concept of legitimacy. The operational framework relies on 53 metrics describing resources, reliability, institutional, public and private support, usable knowledge, MER processes, adaptive management and transparency, equity and justice. On a preliminary basis, the APC framework has been tested on climate change adaptation plans of four cities around the world, namely Vancouver, Durban, Quito and Copenhagen. Specific results of this pilot application suggest that even advanced cities may find areas for improvement in their adaptation policies. Specific issues refer to funding and a rationale allocation of resources to carry out the plan, the regulatory nature of the measures, and the (lack of) MER processes together with the development of learning mechanisms, participation and equity issues. Cities in developing countries show a stronger emphasis on engagement and equity/justice. This suggests that adaptation progress goes beyond well-structured governance and democracy. Still, the relation between adaptation and development and its influence on credibility, should be further explored.

Based on these preliminary results, the APC framework seems adequate to support large-scale decisions related to prioritisation and funding allocation. This index, combined with others that address, for example, urgency to act, might be used effectively to track adaptation and thus to guide private and public investments and the international agenda.

The conceptual and operational framework proposed herein for the assessment of APC may help in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of adaptation policies and, acknowledging the low sample size conditions of the pilot testing, it has the potential to become an extremely helpful indicator for decision making, enabling regional, national and global efforts to be well targeted, funds effectively allocated, and best-practices transferred, ultimately advancing adaptation science and practice (especially as regards adaptation progress measurement efforts).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

This study has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 653522 (RESIN - Climate Resilient Cities and Infrastructures project). MO acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) (FPDI-2013-16631 and IJCI-2016-28835). ESM’s Postdoctoral Fellowship is supported by the Basque Government (POS_2016_1_0089).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marta Olazabal

Marta Olazabal is a research fellow and Head of the Adaptation Research Group at the Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3). She is currently holder of a two-year AXA postdoctoral fellowship grant and a Juan de la Cierva grant by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. Her current interests relate to urban climate adaptation policy and governance, knowledge co-production, systems thinking and concepts and methods to assess urban resilience and sustainability.

Ibon Galarraga

Ibon Galarraga is Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Bath (UK), M.A. Economics at the University of Essex (UK) and B.A. Economics at the University of Basque Country (Spain). He has worked as an environmental consultant for both public and private clients. He has published more than 40 research papers and 14 book chapters in the fields of environmental, energy and climate economics and policy. Ibon has actively contributed to more than 12 international research projects such ECONADAPT (FP7), RESIN (H2020), Water 2 Adapt (IWRM-net). PREEMPT (EC DG ECHO) or CONSEED (H2020).

James Ford

James Ford is a Priestley Chair in Climate Adaptation at the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds, UK. His research focuses on climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability, with a strong focus on the Arctic and Indigenous populations. Alongside his community-based research, he has promoted the development of systematic review approaches in the human dimensions of climate change field, and made major contributions towards efforts to track adaptation policy across scales. The author of >170 articles, Professor Ford is a lead author on the IPCCs Special Report on 1.5C of warming, was a contributing lead author on the Arctic Councils Adaptation Actions for a Changing Arctic assessment, and is editor-in-chief at Regional Environmental Change.

Elisa Sainz De Murieta

Elisa Sainz De Murieta is Post-doctoral Researcher at the Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3). She obtained a BSc. in Geological Sciences from the University of the Basque Country (2001) and a Master’s degree in Environmental Engineering and Management at the School of Industrial Organization in Madrid (2002). She is currently Visiting Fellow at the Grantham Research Institute (London School of Economics), where she is developing a three-year project on climate change adaptation and risk in coastal cities, funded by the Basque Government.

Alexandra Lesnikowski

Alexandra Lesnikowski is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at McGill University. She began working with the Climate Change Adaptation Research Group in 2010 on the development of experimental frameworks for tracking adaptation policies across countries. The results of this research are published in a number of journals, including Nature Climate Change, Environmental Research Letters, and Global Environmental Change. Her doctoral research is focused on advancing these methods for assessing adaptation policy patterns among local governments. She holds a Masters of Arts (Urban Planning) from The University of British Columbia (2014) and a Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) from McGill University (2010).

Notes

1. Here, the term ‘adaptation policies’ is used to refer globally to the group of instruments, strategies and plans that are designed and implemented to achieve climate change adaptation goals.

References

- Adger W, Dessai S, Goulden M, Hulme M, Lorenzoni I, Nelson D, Naess L, Wolf J, Wreford A. 2009. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim Change. 93:335–354.

- Adger WN, Arnell NW, Tompkins EL. 2005. Successful adaptation to climate change across scales. Global Environ Chang. 15:77–86.

- Anderegg WRL, Prall JW, Harold J, Schneider SH. 2010. Expert credibility in climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:12107–12109.

- Anguelovski I, Chu E, Carmin J. 2014. Variations in approaches to urban climate adaptation: experiences and experimentation from the global South. Glob Environ Change. 27:156–167.

- Araos M, Austin SE, Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD. 2015. Public health adaptation to climate change in large cities a global baseline. Int J Health Serv. doi:10.1177/0020731415621458.

- Araos M, Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Austin SE, Biesbroek R, Lesnikowski A. 2016. Climate change adaptation planning in large cities: A systematic global assessment. Environ Sci Policy [Internet]. [accessed 2016 Jul 14]. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1462901116303148.

- Austin SE, Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Parker S, Fleury MD. 2016. Public health adaptation to climate change in OECD countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 13:889.

- Averchenkova A, Bassi S. 2016. Beyond the targets: assessing the political credibility of pledges for the Paris Agreement. London (UK): Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy and Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

- Barnett J, O’Neill S. 2010. Maladaptation. Glob Environ Change. 20:211–213.

- Baynham M, Stevens M. 2014. Are we planning effectively for climate change? An evaluation of official community plans in British Columbia. J Environ Plann Manage. 57:557–587.

- Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Lesnikowski A, Poutiainen C, Barrera M, Heymann SJ. 2014. What drives national adaptation? A global assessment. Clim Change. 124:441–450.

- Bierbaum R, Smith JB, Lee A, Blair M, Carter L, Chapin FS, Fleming P, Ruffo S, Stults M, McNeeley S, et al. 2012. A comprehensive review of climate adaptation in the United States: more than before, but less than needed. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 18:361–406.

- Biesbroek GR, Klostermann JEM, Termeer CJAM, Kabat P. 2013. On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg Environ Change. 13:1119–1129.

- Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Tanabe A, Austin SE, Lesnikowski A. 2018. Data, concepts and methods for large-n comparative climate change adaptation policy research: A systematic literature review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 9:e548.

- Bours D, McGinn C, Pringle P. 2015. Monitoring and evaluation of climate change adaptation: a review of the landscape: new directions for evaluation, number 147. Jossey-Bass.

- Bulkeley H, Broto VC. 2013. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans Inst Br Geogr. 38:361–375.

- Campos I, Guerra J, Gomes JF, Schmidt L, Alves F, Vizinho A, Lopes GP. 2017. Understanding climate change policy and action in Portuguese municipalities: A survey. Land Use Policy. 62:68–78.

- Carmin J, Nadkarni N, Rhie C. 2012. Progress and challenges in urban climate adaptation planning [Internet]. Massachusetts (US): Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/jcarmin/www/urbanadapt/Urban%20Adaptation%20Report%20FINAL.pdffiles/1643/JoAnn files/1643/JoAnn Carmin et al. - Progress and Challenges in Urban Climate Adaptatio.pdf

- Champalle C, Ford JD, Sherman M. 2015. Prioritizing climate change adaptations in Canadian arctic communities. Sustainability. 7:9268–9292.

- Chen C, Doherty M, Coffee J, Wong T, Hellmann J. 2016. Measuring the adaptation gap: A framework for evaluating climate hazards and opportunities in urban areas. Environ Sci Policy. 66:403–419.

- Collins K, Ison R. 2009. Jumping off Arnstein’s ladder: social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Env Pol Gov. 19:358–373.

- Cosens BA. 2013. Legitimacy, adaptation, and resilience in ecosystem management. Ecol Soc [Internet]. 18. [accessed 2016 Nov 23]. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol18/iss1/art3/.

- De Gregorio S, Olazabal M, Pietrapertosa F, Salvia M, Olazabal E, Geneletti D, D’Alonzo V, Feliú E, Di Leo S, Reckien D. 2014. Implications of governance structures in urban climate action: evidence from Italy and Spain. Bilbao (Spain): Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3).

- Drazen A, Masson P. 1994. Credibility of policies versus credibility of policy-makers. Q J Econ. 109:735–754.

- Dupuis J, Biesbroek R. 2013. Comparing apples and oranges: the dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob Environ Change. 23:1476–1487.

- Eisenack K, Stecker R. 2012. A framework for analyzing climate change adaptations as actions. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 17:243–260.

- Engle NL. 2011. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Glob Environ Change. 21:647–656.

- Few R, Brown K, Tompkins EL. 2007. Public participation and climate change adaptation: avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Climate Policy. 7:46–59.

- Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L. 2015. The 4Cs of adaptation tracking: consistency, comparability, comprehensiveness, coherency. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 21:839–859. doi:10.1007/s11027-014-9627-7

- Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Biesbroek R, Araos M, Austin SE, Lesnikowski A. 2015. Adaptation tracking for a post-2015 climate agreement. Nature Clim Change. 5:967–969.

- Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Lesnikowski A, Barrera M, Heymann SJ. 2013a. How to track adaptation to climate change: a typology of approaches for national-level application. Ecol Soc [Internet]. 18. [accessed 2016 Apr 25]. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol18/iss3/art40/.

- Ford JD, King D. 2015. A framework for examining adaptation readiness. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 20:505–526.

- Ford JD, Knight M, Pearce T. 2013b. Assessing the ‘usability’ of climate change research for decision-making: A case study of the Canadian international polar year. Glob Environ Change. 23:1317–1326.

- Füssel H-M. 2007. Adaptation planning for climate change: concepts, assessment approaches, and key lessons. Sustainability Sci. 2:265–275.

- Georgeson L, Maslin M, Poessinouw M, Howard S. 2016. Adaptation responses to climate change differ between global megacities. Nature Clim Change. 6:584–588.

- GomezPuig M, Montalvo JG. 1997. A new indicator to assess the credibility of the EMS. Eur Econ Rev. 41:1511–1535.

- Haasnoot M, Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, Ter Maat J. 2013. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Glob Environ Change. 23:485–498.

- Haasnoot M, van ’T Klooster S, van Alphen J. 2018. Designing a monitoring system to detect signals to adapt to uncertain climate change. Glob Environ Change. 52:273–285.

- Heidrich O, Dawson RJ, Reckien D, Walsh CL. 2013. Assessment of the climate preparedness of 30 urban areas in the UK. Clim Change. 120:771–784.

- Heidrich O, Reckien D, Olazabal M, Foley A, Salvia M, de Gregorio Hurtado S, Orru H, Flacke J, Geneletti D, Pietrapertosa F, et al. 2016. National climate policies across Europe and their impacts on cities strategies. J Environ Manage. 168:36–45.

- Heink U, Marquard E, Heubach K, Jax K, Kugel C, Nesshoever C, Neumann RK, Paulsch A, Tilch S, Timaeus J, et al. 2015. Conceptualizing credibility, relevance and legitimacy for evaluating the effectiveness of science-policy interfaces: challenges and opportunities. Sci Public Policy. 42:676–689.

- Helm D, Hepburn C, Mash R. 2003. Credible carbon policy. Oxf Rev Econ Policy. 19:438–450.

- Hughes S. 2015. A meta-analysis of urban climate change adaptation planning in the. Urban Climate. 14(Part 1):17–29.

- Huitema D, Adger WN, Berkhout F, Massey E, Mazmanian D, Munaretto S, Plummer R, Termeer CCJAM. 2016. The governance of adaptation: choices, reasons, and effects. Introduction to the special feature. Ecol Soc [Internet]. 21. [accessed 2016 Sep 27]. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol21/iss3/art37/.

- ICLEI. 2013. Changing climate, changing communities: guide and workbook for municipal climate adaptation. ICLEI, Canada.

- Jordan AJ, Huitema D, Hildén M, van Asselt H, Rayner TJ, Schoenefeld JJ, Tosun J, Forster J, Boasson EL. 2015. Emergence of polycentric climate governance and its future prospects. Nature Clim Change. 5:977–982.

- Juhola S, Glaas E, B-O L, Neset T-S. 2016. Redefining maladaptation. Environ Sci Policy. 55(Part 1):135–140.

- Kingsborough A, Borgomeo E, Hall JW. 2016. Adaptation pathways in practice: mapping options and trade-offs for London’s water resources. Sustain Cities Soc. 27:386–397.

- Knill C, Schulze K, Tosun J. 2012. Regulatory policy outputs and impacts: exploring a complex relationship. Regul Gov. 6:427–444.

- Lemos MC, Kirchhoff CJ, Ramprasad V. 2012. Narrowing the climate information usability gap. Nat Clim Chang. 2:789–794.

- Lesnikowski A, Ford J, Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Heymann SJ. 2016. National-level progress on adaptation. Nature Clim Change. 6:261–264.

- Lesnikowski A, Ford J, Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Maillet M, Araos M, Austin SE. 2017. What does the Paris agreement mean for adaptation? Climate Policy. 17:825–831.

- Lobell DB, Burke MB, Tebaldi C, Mastrandrea MD, Falcon WP, Naylor RL. 2008. Prioritizing climate change adaptation needs for food security in 2030. Science. 319:607–610.

- Lwasa S. 2015. A systematic review of research on climate change adaptation policy and practice in Africa and South Asia deltas. Reg Environ Change. 15:815–824.

- Lyles W, Stevens M. 2014. Plan quality evaluation 1994–2012: growth and contributions, limitations, and new directions. J Plann Educ Res. 34:433–450.

- Magnan AK. 2016. Climate change: metrics needed to track adaptation. Nature. 530:160.

- Magnan AK, Ribera T. 2016. Global adaptation after Paris. Science. 352:1280–1282.

- Markandya A. 2014. Incorporating climate change into adaptation programmes and project appraisal: strategies for uncertainty. In: Markandya A, Galarraga I, de Murieta ES, editors. Routledge handbook of the economics of climate change adaptation. London: Routledgep. 97–119.

- Measham TG, Preston BL, Smith TF, Brooke C, Gorddard R, Withycombe G, Morrison C. 2011. Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: barriers and challenges. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 16:889–909.

- Millard-Ball A. 2012. Do city climate plans reduce emissions? J Urban Econ. 71:289–311.

- Millard-Ball A. 2013. The limits to planning: causal impacts of city climate action plans. J Plann Educ Res. 33:5–19.

- Mitchell RK, Agle BR, Wood DJ. 1997. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad Manage Rev. 22:853–886.

- Moser SC, Ekstrom JA. 2010. A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:22026–22031.

- Moss RH, Meehl GA, Lemos MC, Smith JB, Arnold JR, Arnott JC, Behar D, Brasseur GP, Broomell SB, Busalacchi AJ, et al. 2013. Hell and high water: practice-relevant adaptation science. Science. 342:696–698.

- Muchadenyika D, Williams JJ. 2017. Politics and the practice of planning: the case of Zimbabwean cities. Cities. 63:33–40.

- Nordgren J, Stults M, Meerow S. 2016. Supporting local climate change adaptation: where we are and where we need to go. Environ Sci Policy [Internet]. [accessed 2016 Jun 10]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901116301617.

- North DC. 1993. Institutions and credible commitment. J Inst Theor Econ (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft. 149:11–23.

- OED. 2013. credible, adj. and n. OED, Oxford English Dictionary.

- Olazabal M, De Gregorio S, Olazabal E, Pietrapertosa F, Salvia M, Geneletti D, D’Alonzo V, Feliú E, Di Leo S, Reckien D. 2014. How are Italian and Spanish Cities tackling climate change? A local comparative study. Bilbao (Spain): Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3).

- Pearce T, Ford JD, Duerden F, Smit B, Andrachuk M, Berrang-Ford L, Smith T. 2011. Advancing adaptation planning for climate change in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR): a review and critique. Reg Environ Change. 11:1–17.

- Pietrapertosa F, Khokhlov V, Salvia M, Cosmi C. 2017. Climate change adaptation policies and plans: A survey in 11 South East European countries. Renew Sust Energ Rev [Internet]. In press. [accessed 2017 Jul 12]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032117310535.

- Preston B, Westaway R, Yuen E. 2011. Climate adaptation planning in practice: an evaluation of adaptation plans from three developed nations. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 16:407–438.

- Preston BL, Rickards L, Fünfgeld H, Keenan RJ. 2015. Toward reflexive climate adaptation research. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 14:127–135.

- Reckien D, Flacke J, Dawson RJ, Heidrich O, Olazabal M, Foley A, Hamann JJP, Orru H, Salvia M, De Gregorio Hurtado S, et al. 2014. Climate change response in Europe: what’s the reality? Analysis of adaptation and mitigation plans from 200 urban areas in 11 countries. Clim Change. 122:331–340.

- Reckien D, Flacke J, Olazabal M, Heidrich O. 2015. The influence of drivers and barriers on urban adaptation and mitigation plans—an empirical analysis of European cities. PLoS One. 10:e0135597.

- Reckien D, Salvia M, Heidrich O, Church JM, Pietrapertosa F, De Gregorio-Hurtado S, D’Alonzo V, Foley A, Simoes SG, Krkoška Lorencová E, et al. 2018. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J Clean Prod. 191:207–219.

- Sarzynski A. 2015. Public participation, civic capacity, and climate change adaptation in cities. Urban Climate. 14(Part 1):52–67.

- Schwarze R, Meyer P, Markandya A, Kedia S, Maleki D, Lara M, Sudo T, Surminski S, Anderson N, Olazabal M, et al. 2016. Economics, Finance, and the Private Sector (Chapter 7). In: Rosenzweig C, Solecki W, Romero-Lankao P, Mehrotra S, Dhakal S, Sa I, editors. Climate change and cities: second assessment report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network (UCCRN). New York (NY): Cambridge University Press. 225.

- Sherman M, Berrang-Ford L, Lwasa S, Ford J, Namanya DB, Llanos-Cuentas A, Maillet M, Harper S, Research Team IHACC. 2016. Drawing the line between adaptation and development: a systematic literature review of planned adaptation in developing countries. Wires Clim Change. 7:707–726.

- Shi L, Chu E, Anguelovski I, Aylett A, Debats J, Goh K, Schenk T, Seto KC, Dodman D, Roberts D, et al. 2016. Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nat Clim Chang. 6:131–137.

- Smith JB. 1997. Setting priorities for adapting to climate change. Glob Environ Change. 7:251–264.

- Stevens MR. 2013. Evaluating the quality of official community plans in southern british columbia. J Plann Educ Res. 33:471–490.

- Stults M, Woodruff SC. 2016. Looking under the hood of local adaptation plans: shedding light on the actions prioritized to build local resilience to climate change. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change. 22:1249–1279.

- Sud R, Mishra A, Varma N, Bhadwal S. 2015. Adaptation policy and practice in densely populated glacier-fed river basins of South Asia: a systematic review. Reg Environ Change. 15:825–836.

- Tilleard S, Ford J. 2016. Adaptation readiness and adaptive capacity of transboundary river basins. Clim Change. 137:575–591.

- Tribbia J, Moser SC. 2008. More than information: what coastal managers need to plan for climate change. Environ Sci Policy. 11:315–328.

- Weichselgartner J, Kasperson R. 2010. Barriers in the science-policy-practice interface: toward a knowledge-action-system in global environmental change research. Glob Environ Change. 20:266–277.

- Woodruff SC, Stults M. 2016. Numerous strategies but limited implementation guidance in US local adaptation plans. Nature Clim Change. 6:796–802.

APPENDIX 1 – TABLE 1 EXTENDED

Table A1.1 is based on Table 1 of the manuscript and includes metrics, evaluation method for each metric and the pilot application including the scores for each city.

APPENDIX 2 – LIST OF REVISED DOCUMENTS AND SOURCES

These documents are considered to be the latest update (as of March 2017) on the general adaptation policy of the city. In some cases, there are previous documents that have been taken into account (Durban and Quito) or other documents covering specific projects or initiatives emerging from the general plan (Vancouver and Copenhagen). First adaptation-related policies appear in documents published in 2006 (Durban) and 2009 (Quito). In the case of Vancouver (2012) and Copenhagen (2011), the documents revised are the first ones containing adaptation-related policies.

Table A2.1. List of revised documents and sources - Vancouver

Table A2.2 List of revised documents and sources – Durban

Table A2.3. List of revised documents and sources - Quito

Table A2.4. List of revised documents and sources – Copenhagen