ABSTRACT

The current study examines gaps between climate change and rapid urbanisation sub-Saharan Africa. Through a combined analysis of remotely sensed and meteorological data, the study revealed the extent of urban microclimate change trends within a few decades. Thus, upward changes in microclimate – temperature of nearly 2°C was witnessed in 2018 (27.7°C) against 25.9°C of 1980s. Whereas, the city expanded from 39.2 km2 in 1986 to 256 km2 in 2018. These changes witnessed in urban form and climate are attributed to rapid urban expansion and poor planning system that fails to preserve and protect the city’s green and blue infrastructure. The picture of the situation in Kano gives insights into the enormous challenges before cities in developing world to cope with local and global climate change risks. Indeed, this situation calls for an integrated approach to addressing climate change from within and without cities themselves. It is imperative on policymakers to increase expenditure on urban planning, financing adaptation strategies through urban planning, and strengthening of institutions of urban planning.

Introduction

The disconnection between urban planning institutions and its implementation remains a serious challenge in the developing countries. Urban planning creates opportunities for addressing global warming and climate change and supporting climate change adaptation and mitigation. The four key areas for transforming global warming beyond the dangerous levels outlined by the IPCC (Citation2018) are energy, land use, industry and cities. All these variables are directly related to the process of urbanisation and spatial planning of urban areas. Contrary to urban areas in western countries, urbanisation in developing world comes with suburbanisation resulting in the formation of different urban forms like edge, outer cities, gated communities, gentrification, inequalities, environmental degradation, insecurity and poor planning among others (Hamnett Citation2005).

The United Nations reveals that currently 55% of the world’s population is living in urban area, and that by 2050 about 68% of the world’s population will be living in the cities (UN DESA/PD Citation2018). This rural-urban population imbalance gave rise to new configuration of high urban population concentration in large cities such as Mexico City, Sáo Paulo, Lagos, Jakarta and Shanghai with attendant implications on the changing form, economic base and social structure of immense importance for urban life today and in the future (Hamnett Citation2005). By focusing attention on megacities, there is risk of ignoring other cities where critical challenges such as rapid growth, poor investment in urban infrastructure and weak urban planning may exacerbate vulnerability to climate change.

Africa remains the least urbanised continent, the nature of informality and history of its urbanisation leaves much to be appreciated in the light of changing climate. With a growth rate of 3.31% per year, the urban population of Africa is expected to double from 370 million to over 750 million between 2007 and 2030 (ADB, Citation2017). In East Africa, the world’s fastest urbanising region, the urban population will double in 9 years. In Southern Africa, where the population was 45.6% urbanised in 2007, growth rate is relatively low, but still far outstripped those of the rural population. In general, migrations from rural areas into cities comprise of a reducing share of the new urban population while natural growth from within the cities now plays an increasing role (Ticoli et al., Citation2015; Bhagat Citation2017).

According to Petralla (Citation2007), African urban structure has two main characteristics. The first is the disproportionate concentration of population, activities, resources and investments in the largest city in the country at the expense of other cities and towns. The second is the emergence of urban corridors, with large metropolises in relative proximity merging in huge regional systems as found along the Gulf of Guinea or in the Gauteng Region in South Africa. Often, these characterizations relation to climate change vulnerability and city management challenges. Invariably, urban form and configurations have links with climate change, urbanisation and development of institutions of sustainable development.

For instance, green areas in and around urban areas act as a carbon sink and their disappearance may have an impact on rainfall, temperature and the relative humidity in an urban area (Misni et al. Citation2015; Nero et al. Citation2017). Studies show potential of large population in altering climatic and environmental variable. For example, Chapman et al. (2014) points how that urban growth posed a threat to urban climate through increasing the risk of rising temperature there-by creating an island-like urban ring often referred to as urban heat island (UHI) effect. Urban condition is also associated with an increasing impervious surfaces, which reduce the amount of atmospheric moisture, contributes through evaporation and transpiration latent heat flux (Grimmond and Oke Citation1991). Furthermore, urban area lowers the albedo and nocturnal radiation, and through traffic releases more carbon that is likely to increase the risk of climate change (Qin Citation2015; Bai et al. Citation2018).

Urban planning is a key issue of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). SDG 11 in particular aimed to make cities and settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. The urban planning undertone calls for the development of urban framework in developing countries that are grappling with rapid population growth. In connection with the growing recognition of urbanisation as an engine of sustainable development, in 2016, the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development approved the New Urban Agenda (NUA) as a means to re-address the way cities and human settlements change; and to plan, design, finance, develop, govern and manage cities in better ways. There are other important recent global agreements connected with urban environment such as the ‘Paris Agreement’ and the ‘Sendai framework for Action on Disaster Risk Reduction’ that emphasise the role of urbanisation and local authorities in promoting resilience and risk reduction as well as in mitigation and adaptation to climate change around the world (UN Habitat Citation2016). These agreements are clear manifestations that all are not well in many urban environments. It also translates on the need to provide an articulate action for the management of urban environment.

There were various attempts in the past to provide the needed framework for urban development in Kano Metropolis. The formal urban development planning in Kano City however, started with the proposed Trevallion Master Plan of 1963, a 20 years development plan for the city and other major towns in Kano State. A Metropolitan Planning and Development Authority (KMPDA) came into being in 1969 to ensure compliance to the proposed master plan. The plan was expected to provide an urban development framework for the former Kano State (comprises of present day Kano and Jigawa States). In the year 1976, Urban Development Board (UDB) was created with similar powers to KMPDA, but responsible only for the 12 designated urban areas in the state. The main objective of the then UDB in Kano, as stated in Kano State Urban Development Board pamphlet was to create a suitable environment in Metropolitan Kano and other urban centers within Kano State. The document aims to create a metropolis that is safe, convenient and good for a healthy living; and to create conscience-planning processes in the minds of the people (Home Citation1986). The then UDB, now Kano Urban Planning Development Authority (KNUPDA) is therefore responsible for managing rapid urban growth and poor living condition. KNUPDA is also expected to enjoy a single-mindedness of purpose and relative freedom from bureaucratic, financial and political constraints. However, the institution is now bedeviled with government interference that translates into the distortion of the laid down principle inherent in its saddled operations (Odunlami Citation2014). It is against this background, this study searches for a link between urbanisation and climate change in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. In searching for the links the following research, critical questions on the nature of urban growth in Kano Metropolis, city’s climate changes overtime and the extent of the city’s planning authority to addressing climate change are formulated.

Conceptual framework

The world urban population based on projection is to reach 5 billion in the year 2030 and will by 2050 to reach 6.4 billion people. The large share of this growth is expected to be located in developing countries, particularly Africa and Asia where the urban population is expected to double between 2000 and 2030 ([ADB] African Development Bank Citation2017; Silvaa et al. Citation2012; UN DESA/PD Citation2018). This rapid increase in population particularly in developing countries comes with attendant implications in the transformation of urban economy, alteration of urban ecosystem to accommodate the spontaneous surge in population. These exacerbate land clearance for urban development and the demand for goods and resources by urban residents, both in the past and present, are the major drivers of regional land use change, such as deforestation, which has reduced the magnitude of global carbon sinks (Grimmond, Citation2007).

Associated with this urban growth is the conversion of green areas into residential areas with corresponding urban building density and concretisation of the urban landscape. This change of urban landscape alters the solar energy receipt, total albedo, water cycle among others. The links between urbanisation and the global change in climate remain complex and intricately interwoven. The complexity is such that may have a profound effect on temperature changes of the affected locations (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al. Citation2005). They also reduced the carbon sink and ability of the surface to absorb excess water, thereby making the area more prone to floods (Bai et al. Citation2018).

Some of the consequences of urbanisation in most developing countries connect to the increase in automobiles and more trips generation and emergence of industries. Svirejeva-Hopkins et al. (Citation2004), reveals that more than 90% of anthropogenic carbon comes from the cities, this is an indicator for rapid temperature change in situ.

It is against this background of positivizing global warming that urban cities are continuously threatened and majorly affected by greenhouse gases both directly and indirectly, as they are the major areas and sources of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels for heating and cooling; industrial processes; transportation of people and goods and so forth.

The urban bias in resource allocation in the three development plan periods in Nigeria for the periods of (1962–68, 1970–74 and 1975–1980) attests to the growth of urban centres in Nigeria especially due to rural-urban drift (Filani Citation1993). This destabilisation in the rural-urban population equilibrium sets a new form of causal interactions on the urban landscape. This growth is most severe in state capitals, which become hubs of socioeconomic development. It is in this connection that the searching for the links; urbanisation and climate change relations in Kano Metropolis is examined as climate change due to global warming is recently confirmed by significant observed increases in average temperatures and its impacts cannot be overemphasised on urban settlements that houses millions of people in Nigeria (Ekanade et al., Citation2008).

Materials and methods

Study area

Kano metropolis is the capital of Kano State and is located between latitudes 11°50ʹ and 12°07ʹ North of the Equator and longitudes 8°22ʹ and 8°47ʹ East of Great Meridian (Mohammed Citation2015). It is comprises of eight local government, four of which formed the significant portion in terms of land mass in the vestigial ancient city wall enclosure, these core local government areas are Dala, Fagge, Gwale and Kano Municipal. Nassarawa and Tarauni local governments formed the nucleus of Metropolitan and enveloped by Kumbotso and Ungogo. Kano metropolis is the capital Kano State, the most populated state in Nigeria. It is a great centre of human population between the Niger and the Nile deltas and entry port to the Saharan desert (Madugu Citation2016). It is located at the centre of the West African larges plain, Hausa plain and the capital of Kasar Kano. According the Kano Chronicle Kano had been in existence prior to 10th Century, and the city claimed to have sprung from Dala Hill to areas around Jakara stream (Gambo Citation2014).

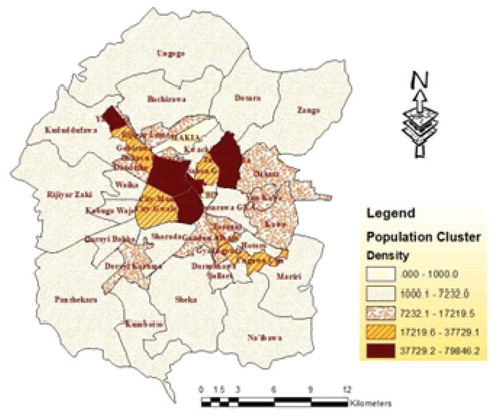

The present Kano Metropolis houses over 4.5 million people and in many locations within the city, the density is well over 20,000 person per square kilometre based on National Population Commission’s projection (NpopC Citation2010). It houses five industrial estates, over 10 major commercial areas and four universities. As Kano City continues to grow in terms of population and physical expansion, so does its commercial and industrial activities. Residential areas constitute most part of the city, most of which lacks planning (Sani Citation2006; Dankani, Citation2016). In addition, the city contains 10 major commercial units. The units are: the Kurmi Markets being the traditional in origin, the CBD which started as colonial shopping complex and the Sabon Gari Market being a hybrid of the two (Liman and Adamu Citation2003). There are also major markets like Kantin Kwari, Yankaba, Kofar Ruwa, Kasuwar Rimi and Yanlemo. Kano Metropolis is shown in .

Sources of data

Data used for the study include: the climatic data (rainfall and temperature) sourced from Nigeria Metrological Office (Nimet); and the Landsat imageries which consist of Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper 1986 and 2003 and Landsat 8 of 2016 were downloaded from the USGlovis site, and were used for landuse mapping, vegetation degradation analysis and surface temperature extraction. In addition, documentary data on Kano City’s growth, urbanisation and urban planning were consulted by the study. Equally conducted is a key informant interview with urban planning authority, a director in the ministry of land and a private urban planner with over four decades experience in the city.

Data analysis

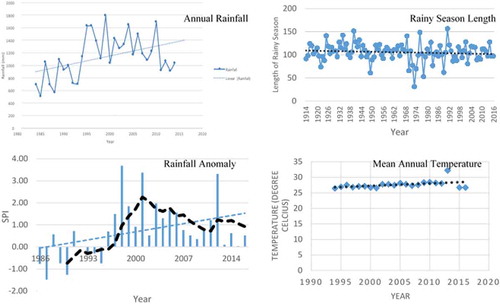

Climate data obtained were analysed to see the changing trends and pattern. The daily rainfall data obtained for 30 years (1986–2016) was analysed to determine number of rainy days; the total annual rainfall; and the annual standardise precipitation indices (SPI). SPI is compute by dividing the difference between the normalised seasonal precipitation and its long-term-seasonal mean by the standard deviation (Mohammed et al. Citation2015). The presentation of the results of the analysis consists of line graphs with linear trends as insert to depict the pattern.

The landsat satellite imageries were processed in GIS environment using ArcGIS 10.3 software. The imageries were first pre-processed, stacked and subset. The classification was done using hybrid method combining both the supervised and unsupervised techniques. Training sites were selected using high-resolution images of the area and based on the researchers’ familiarity of the study site. For mapping landuse, the area was divided into built and non-built areas. The non-built areas composed of green and open areas, while the built areas include all other uses: residential, industrial, commercial, administrative, roads and other urban uses. As submitted by Mabogunje (Citation2005), urban is characterised by dominance of built areas and few open and green areas. The NDVI was computed to detect vegetation change in the area and how it is changing overtime. The land surface temperature (LST) was computed based on the procedure suggested by Qin et al. (Citation2010). The result of the interviews data were used to explain some of the empirical findings.

Results and discussion

Kano Metropolitan’s growth rate currently stands at 3.9, one of the highest in Nigeria. The city’s growth is above the Nigeria average of 3.2 (NpopC Citation2010), one of the fastest urban growth in Africa (UN DESA/PD Citation2018). reveals the population growth of Kano City and the metropolis. Currently the metropolis has a population of 4.5 million with average density of 15,000 persons per km square. In the densely part of the city, the population is greater than 37,000 per square kilometres. All these areas were largely green and extensively cultivated areas before 1967 when the city assumes the status of the state’s capital. With the declaration of Kano as a state capital large influx of people were recorded (Barau Citation20072017b).

Table 1. Kano’s population from 16th century to date.

Indeed, Odunlami (Citation2014) asserts that Kano City has been growing without planning guide, and even in planned areas (formally called layouts) planning were largely distorted. Some of the repercussions of the unanticipated population influx to the city include the taking over of initially cultivated area by urban (Barau Citation20072017b); and the disappearance of urban open and green parks (Maiwada Citation2000). Other consequences were land degradation and climate modifications (Barau Citation20072017b; Barau et al. Citation2014). Indeed, evidence of urban induced increase in temperature was noticed in the metropolis (Idris Citation2005; Umar and Kumar Citation2014). Studies connected the temperature increases to recent domination of housing roofs by blue and brown colour aggravating the temperature of the city by lowering the albedo and increasing the heat adsorption (Barau et al. Citation2015; Bai et al. Citation2018). The implications of this rapid change in city’s microclimate which Barau (Citation1999) noticed is creates a temperature differences of 2–4°C between dense and less dense areas contrastingly, a few years after, Idris (Citation2005) found a temperature difference of 4–6°C.

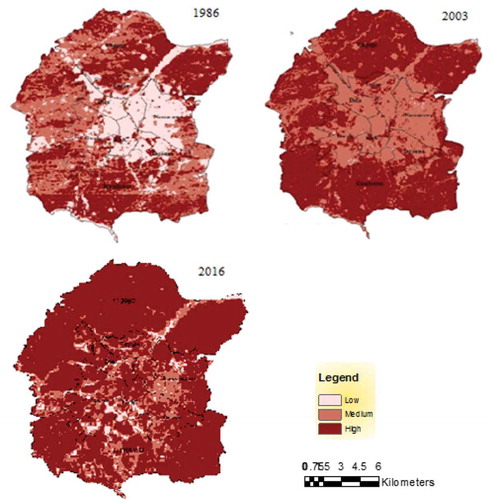

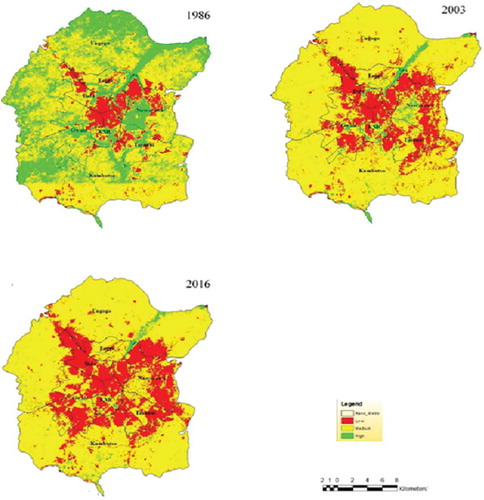

Over the years, there has been consistent increase in urban landuse in Kano Metropolis (Table, 2). The extent of built-up area had increase from 39.2 km2 in 1986 to 256 km2 in 2016, an increase of more than six times. The open and green areas however declined from 93% in 1986 to 55.8% in 2016.

The rapid growth witnessed in the city () is more of an urban sprawl fueled by lack of effective urban planning (Maiwada Citation2014; Barau, Citation2017a). Ineffective urban planning can also be because of poor funding of planning authorities. A retired planning officer asserts that, ‘Kano Urban Planning Authority has been neglected by the state government since 1991’. Another retired Director of Planning in the Agency added that, ‘Kano city is witnessing unprecedented growth but there are little efforts to equip the agency or update its powers to address the planning challenges that have continued to crop up’. The respondent noted that ‘adaptation and mitigation strategies are not priorities of the agency at the moment’. In other words, investment in urban planning and combatting climate change are not key policy strategies despite the fact that Kano city has been experiencing uncommon flood incidents since the late 1980s and keeps exacerbating since then.

Table 2. Urban expansion in Kano Metropolis (1986–2016).

The changing climate in Kano manifests through many climatic elements among which temperature is very central. Evidently, the surface temperature increase can be observed in where the surface temperature is shown to have increased significantly between 1986 and 2016. The minimum and maximum surface temperature for 1986, 2003 and 2016 are 11.4–27.9°C, 14–9-44.3°C and 17.4–56.2°C, respectively. This points to increase in surface temperature in the city as the population and built areas continue to increase.

In general, the figure reveals both minimum and maximum temperature in the study have experience change over space and time. This is in tandem with findings of previous studies (Idris Citation2005; Umar and Kumar Citation2014) which attributed the surface temperature increase increased to anthropogenic activities and land use change in particular. As land use change induces change in urban microclimate, it is possible to attribute rising temperature to the failure of urban planning to separate land use activities in the manner that supports temperature-attenuating land uses such as wetlands and green areas. However, poor financing of urban planning sector could be the main driver of weakening role of urban planning agencies to face the challenge of climate change.

There is clear semblance between surface temperature () and vegetation lost () using NDVI in the area. It was clear from NDVI map that the metropolitan Kano is undergoing vegetation degradation with green and vegetal lands disappearing. reveals increased in low NDVI areas between 1986 and 2016 indicating the loss of vegetation to build areas. The is hardly any significant vegetation rich area in the 2016 NDVI map except the riparian vegetation along river Jakara in the north eastern part of the area. There is relatively moderate greening in Nassarawa GRA, which remain the most planned part of the in spite of the distortions.

As pointed by Barau (Citation2014, Citation2017a, Citation2017b) and Maiwada (Citation2000, Citation2014), the green areas are rapidly disappearing from the city’s landscape. Contrary to the popular greening assertion made in the neighbouring Sahel Region (Mortimore and Adams Citation2001; Olssona et al. Citation2005), Kano city located in Sudan Savannah is facing serous degreening of its open and green spaces as a result of pressing demands for urban land.

Metrological data reveals increase in temperature in the area as indicated by , on the other hand analysis of rainfall in Kano reveals increase in total annual rainfall (Mohammed et al. Citation2015). However, the temperature shows positive trend conforming IPCC (Citation2007) which pointed out that temperature increase is a consequence of climate change. This reports that areas in the northern hemisphere were more prone to temperature increase. Thus, Kano City experiences increase in temperature. Indeed, even the mean annual temperature had increased from 25.9°C in early 1980s to 27.7, an increase of nearly 2°C (Olofin Citation1987). This is also attributed to human induced factors such as population and informal urbanisation, which has characterised Kano City and many other cities and towns in developing countries.

Conclusion

By focusing on an example of Kano City, this paper sheds light on the risks of climate change in urban areas of developing country where informal urbanisation and weak planning system prevail. The drivers were anthropogenic including landuse dynamics, vegetation lost and degrading lands. Weak and poorly funded institutions and agencies undermine poor implementation of urban planning system, even where it exists as the example of the situation in Kano demonstrates. Under such situations, the changing climate and its consequences become noticeable and impact felt by poor people living in the cities and towns of developing counties. From the findings of this study, there are wide gaps and missing links between the current urban planning system and climate change adaptation and mitigation options. Poor funding of the urban planning sector and lack of investment in infrastructure are serious challenges that developing countries must learn to address as preliminary actions for combatting climate change. Within the context of partnerships outlined under the SDGs, it becomes imperative on developed countries to increase investment in climate change adaptation in developing countries. From example of Kano, there is generally poor planning at metropolitan level as observed by most previous studies. The recent erratic floods experienced in the cities such as Kano also underscores the urgent need for financing planning agencies to cope with rehabilitation of affected infrastructure such as roads, schools and public housing. This is particularly important in urban areas where funding where urban development is poor and cities are themselves largely informal. Financing of urban planning system to address climate change risks needs to be innovative and inclusive.

Urban Kano represents a good example of how urbanisation poses risks of climate change and at the same exposes poor cities inability conforms to what it needs to realise NUA and SDG 11 instruments. Implementation of SDG 11 and NUA require funding which entails capacity building for planners and urban managers as well as investment in infrastructure and facilities for planning agencies. The UN Habitat (Citation2016) preaches for critical connection between environment, urban planning and governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Murtala Uba Mohammed

Murtala Uba Mohammed is currently a staff and PhD candidate in Geography Department Bayero University, Kano. His research interest include urban geography, development geography and GIS applications.

Nura Ibrahim Hassan

Nura Ibrahim Hassan is a PhD candidate in Geography Bayero University, Kano. He previously worked for Nigeria Infrastructural Advisory Facility (NIAF), a program supported by DFID, UK. Nura interest in on population and development geographies.

Murtala Muhammad Badamasi

Murtala Muhammad Badamasi (PhD Geography) is a senior lecturer in the department of Environmental Management and Centre for Dryland Agriculture (CDA), Bayero University Nigeria. His research interest include landscape ecology and remote sensing applications.

References

- [ADB] African Development Bank. 2017. Urban development: issues, challenges, and ADB‘s approach news letter.Abidjan, Ivory Cost. Accessed 2017 Sep 25.

- Bai X, Dawson RJ, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Delgado GC, Barau AS, Dhakal S, Dodman D, Leonardsen L, Masson-Delmotte V, Roberts RC, et al. 2018. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nat Int J Sci. 555:23–25.

- Barau AS. 1999. Impact of urban growth on the climate of Kano Metropolis. An unpublished B.Sc thesis submitted to geography department, Bayero University, Kano.

- Barau, A.S. 2017a. Land degradation and environmental quality decline in urban Kano. In: Isa MA, editor. Kano: the state, society and economy 1967–2017. Kano State Government, 141–170.

- Barau AS, Maconachie R, Ludin ANM.,Abdulhamid A. 2015. Urban morphology dynamics and environmental change in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy. 42:307–317.

- Barau AS 2017b. Ecological cost of city growth in Africa: the experience of Kano in Nigeria. Accessed 2017 Aug 3. http://uaps2007.princeton.edu/papers/70131.

- Barau AS. 2014. The emir’s palace. In: Tanko AI, Momale SB, editors. Kano environment, society and development. Landon: Adoni and Abbey publisher limited; p. 91–110.

- Barau AS, Maconachie R, Ludin ANM, Abdulhamid A. 2014. Urban morphology dynamics and environmental change in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy. 42:307–317.

- Bhagat RB. 2017. Migration and urban transition in India: implications for development. United Nations expert group meeting on sustainable cities, human mobility and international migration, Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs United Nations Secretariat New York.

- Chapman S, Watson JEM, Salazar A, Thatcher M, McAlpine CA. 2014. The impact of urbanization and climate change on urban temperatures: a systematic review. Landscape ecol. Springer. 32:1921–1935.

- Dankani I. 2016. Mutidimensional challenges to urban renewal in Kano walled city, Nigeria. Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 4(8):01–08.

- Ekanade O, Ayanlade A,Orimmogunje IOO. 2008. Geospatial analysis of potential impact of climate change on coastal urban settlement of Nigeria for the 21st century. J geogr reg plann. 1(3):049–057.

- Filani MO. 1993. Transport and rural development in Nigeria. Ibadan, Nigeri: Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd. 096-6923/93/040248-07.

- Gambo B. 2014. Origin and growth of Urban Kano. In: Tanko AI, Momale SB, editors. Kano environment, society and development. Landon: Adoni and Abbey publisher limited; p. 67–80.

- Grimmond S. 2007. Urbanization and global environmental change. local effect of urban warming: p. 83–88.

- [IPCC] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Climate change 2007: working group I: the physical science basis: projection of future change in climate. IPCC, Paris

- [KUTPO] Kano Urban Transport Project Office 2017. Conceptual design of pilot scheme for lowering carbon emission in Old Kano City. A report by LAMATA under the global environmental facility grant to Kano State Government by the World Bank. Kano State, Nigeria.

- [IPCC] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2018. Global warming report of 1.5°C: an IPCC special report on the impact of global warming of 1.5 oC above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse pas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response on the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and effort to eradicate poverty.IPCC, Paris

- Grimmond CSB, Oke TR. 1991. An evapotranspiration-inter-ception model for urban areas. Water Resour Res. 27(7):1739–1755.

- Hamnett C. 2005. Urban Forms. In: Cloke P, Crang P, Gordon M, editors. Introducing human geography. 2nd ed. Hodder Arnold (2 Park Square): Milton Park, Abigdon, Oxon OX14, 4 RN Publishers; p. 425–438.

- Home RK. 1986. Urban development boards in Nigeria: the case of Kano. London: Butterworth and Co Publishers Ltd.

- Idris HA 2005. Geographical study of heat island phenomena in Kano Metropolis [Unpublished thesis submitted for the award bachelor of science geography]. Kano: Bayero University.

- Liman MA, Adamu YM. 2003. Kano in time and space: from a city to a metropolis. In: Hambolu MO, editor. Perspective on Kano British Relations. Kano: Gidan Makama Museum; p. 144–169.

- Liman MA 2015. Spatial analysis of the decline of industries in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria [A PhD thesis submitted to the department of geography]. Zaria: Ahmadu Bello University.

- Mabogunje AL. 2005. Global urban poverty research agenda: the African case. Being a paper presented at a seminar on “global urban poverty: setting the research Agenda” organized by the comparative urban studies project of the woodrow wilson international center for scholars and held in Washington D.C.. on Thursday, December 15, 2005, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/MabogunjePaper.doc.

- Madugu YU. 2016. Transportation and precolonial Kano economy. Arewa House J. 4(4):132–153.

- Maiwada AD. 2000. Disappearing open spaces in Kano Metropolis in Issues in land development and administration. In: Falola JA, Ahmed K, Liman MA, Mawada AD, editors. Proceeding of the National workshop on land administration and development in Northern Nigeria, department of geography. Kano: Bayero University, 3–9.

- Maiwada AD. 2014. Urban planning in the context of rapid growth. In: Tanko AI, Momale SB, editors. Kano environment, society and development. Landon: Adoni and Abbey publisher limited; p. 365–374.

- Misni A, Jamaluddin S, Kamaruddin SM. 2015. Carbon sequestration through urban green. Plann Malaysia. xiii:101–122.

- Mohammed MU 2015. Location analysis of filling stations in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria [An M.Sc. thesis submitted to the Department of geography]. Kano: Bayero University.

- Mohammed MU 2018. Spatio-temporal analysis of noise pollution in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. [Being a PhD seminar presented at the department of geography]. Kano: Bayero University.

- Mohammed MU, Abdulhamid A, Badamasi MM, Ahmed M. 2015. Rainfall dynamics and climate change in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. J Sci Res Rep. 7(5):386–395.

- Mortimore MJ, Adams WM. 2001. Farmer adaptation, change and ‘crisis’ in the Sahel. Global Environ Change. 11:49–57.

- Nero BF, Callo-Cachaa D, Annigb A, Danic M. 2017. Urban green spaces enhance climate change mitigation in cities of the global south: the case of Kumasi, Ghana. Procedia Eng. 198:69–83.

- NpopC. 2010. 2006 population census priority tables volume 1–15. National Population Commission, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Odunlami T. 2014. Management problems of urban land development in Nigeria: A case of the Kano State urban development board. Land Dev Stud. 6(1):41–55.

- Olofin EA. 1987. Some aspect of the physical geography of the Kano region and related human responses. Department lecture series no. 1. Bayero University Kano, Nigeria.

- Olssona L, Eklundhb L, Ardo J. 2005. A recent greening of the Sahel—trends, patterns and potential causes. J Arid Environ. 63:556–566.

- Petralla L. 2007. Urban Africa-challenges and opportunities for planning at a time of climate change. ISOCART Rev. 06:52–76.

- Qin Y. 2015. Urban canyon albedo and its implication on the use of reflective cool pavements. Energy Build. 96:86–94.

- Qin Z, Karnieli A, Berliner P. 2010. A mono-window algorithm for retrieving land surface temperature from Landsat TM data and its application to the Israel-Egypt border region. Int J Remote Sens. 22(18):3719–3746.

- Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Seto K, Simon D, Solecki W, Kraas Fand Laumann G 2005. Science plan: urbanization and global environmental change. IHDP Report 15 International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change. Bonn.

- Sani AS 2006. Analysis of low-income housing in Kano, Nigeria [A thesis submitted for the award of PhD in town planning]. UK: St Clement University.

- Silva J, Kernaghanb S, Luquec A. 2012. A systems approach to meeting the challenges of urban climate change. Int J Urban Sustainable Dev. 1–21.

- Svirejeva-Hopkins A, Schellnhuber HJ, Pomaz VL. 2004. Urbanised territories as a specific component of the global carbon cycle. Ecol Modell. 173:295–312.

- Tacoli C, McGranahan G, Satterthwaite D. 2015. Urbanization and rural-urban migration and urban poverty. Landon: International Institute for Environment and Development (iied) working paper.

- Umar UM, Kumar JS. 2014. Spatial and temporal changes of urban heat island in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. J Eng Sci Technol. 1(2):20.

- UN DESA/PD. 2018. Revision of world urbanisation prospects: the 2018 revision. New York (NY): United Nations.

- UN Habitat. 2016. Urbanization and Development: emerging Futures World Cities Report 2016. First published 2016 by United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2016. Accessed 2017 Oct 11. www.unhabitat.org.