ABSTRACT

This paper explores the scope for upscaling and transnational transfer of participatory landslide risk management strategies for informal settlements in Latin America. Drawing on lessons from transdisciplinary action-research in three neighbourhoods in Medellín, Colombia, and one in São Paulo, Brazil, the paper discusses how bottom-up approaches were developed to co-produce landslide risk management in both Global South cities, in a way that optimises the collaboration between communities and relevant governmental bodies. The analysis focuses on mitigation and ‘agreement-seeking’, from the perspectives of scale, power and knowledge, which help understand the parallels between co-production of landslide risk management and co-production of urban services. Two key conclusions are that landslide risk management should be built into neighbourhood upgrading and management, and that both community and the state have stronger roles to play in landslide risk management from their respective capacities. The paper also reflects on the role of academia in enabling co-production of landslide risk management through engaging with local communities.

Introduction

Informal settlements growing up steep hillsides and ravines across Latin American cities are often exposed to landslides, which are a major cause of death and loss of livelihoods in the Global South (Petley Citation2012). In order to reduce disasters, we need to anticipate these through managing risk. Many ways of managing landslide risk are known, ranging from building physical protection barriers to raising awareness to prepare communities. However, these measures are often difficult to implement in the Global South, not only because of lack of resources but also due to complex social, economic, environmental, political and institutional reasons.

The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN/ISDR), published in 2002, provided a review of disaster reduction initiatives throughout the world responding to increasing concerns about ‘the impact of disasters’ that occurred between the 1970s and 1990s (UN/ISDR, p. 9). Whilst the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR) was prompted by the scientific community in order to ‘expand the scope of scientific and technical abilities in disaster reduction’ (UN/ISDR, p. 9), the human dimension – encompassing all that is economic, social and political – has emerged as an equally important aspect of risk reduction.

Maskrey (Citation1984, Citation1989, Citation2011) was an early proponent of addressing the social dimension of disaster risk management at a local level through his work with the NGO PREDES (Centre for Disaster Prevention and Studies), created in Peru in 1983 to work with a range of communities that had suffered disaster impacts. PREDES linked the technical understanding of disaster with understanding how the socio-territorial inequalities of the development process concentrated disaster risk in poor communities (Maskrey Citation2011). In the face of such risk, poor urban communities adopt ‘coping strategies’, but there is a limit to how much these can achieve. There is a ‘substantial gap between what household and communities need or do to deal with risk and disasters and the way in which urban development actors support them’ (Wamsler Citation2007, p. VI). Indeed, addressing this gap is central to Maskrey’s arguments that community-based disaster risk management means empowering communities by changing their roles from objects to subjects (Maskrey Citation2011). Thus, persuading governments to participate in community-led programmes is a key issue (Maskrey Citation1984). This paradigm shift from top-down disaster risk management to the engagement of a wider range of stakeholders has become mainstream in the approach of a range of multilateral organisations, governments, NGOs and risk-reduction agencies (Maskrey Citation2011) and has been enshrined in international initiatives such as the Sendai Partnerships 2015–2025 for Global Promotion of Understanding and Reducing Landslide Disaster Risk (ISDR-ICL Citation2015). Experiments with community-based disaster risk management in various research projects during the 1980s and 1990s have evolved into explorations of co-produced disaster risk management approaches in the last decade, but we would argue that co-production has not become established to the same degree as in other fields of development. By co-production, we refer to ‘the provision of services (broadly defined, to include regulation) through regular, long-term relationships between state agencies and organized groups of citizens, where both make substantial resource contributions’ (Joshi and Moore Citation2004, p. 40).

This paradigm shift has developed further in recent research and experimentation with co-production in the provision of urban services such as water and sanitation, waste management, mobility and energy, relying on contributions from residents as well as from public or private agents (e.g. Mitlin Citation2008; Batley and Mcloughlin Citation2010; Allen Citation2012; McGranahan Citation2013; Moretto and Ranzato Citation2017). These approaches have been found to offer solutions to low-income communities that are inadequately provided – or not provided at all – with conventional urban services available to middle- and high-income neighbourhoods. These are indeed the type of poor community identified by Maskrey as needing empowerment to manage risk. So, to what extent are co-production approaches developed for the delivery of these services relevant to disaster risk management in such communities? How can disaster risk management be co-produced, overcoming barriers of power and knowledge? Can vulnerable communities in informal urban settlements become key protagonists in addressing their exposure to risk, through co-production?

This paper presents and analyses co-production approaches to landslide risk management which were developed through an action-research process (2016–2019) first undertaken in the city of Medellín, Colombia, and then extended to São Paulo, Brazil. The article first reviews the literature on disaster risk management co-production and compares this with key aspects of urban services co-production. In doing so, it sets out a framework based on scale, power and knowledge to analyse the processes for co-production of landslide risk management that were experimented with through action-research projects in these two cities. The paper briefly describes the components and related methodologies of these projects (perception and narratives, monitoring, mitigation and ‘agreement-seeking’). This sets the scene for a detailed discussion of mitigation and ‘agreement-seeking’ in the following three sections, applying the lenses of scale, power and knowledge, respectively. The paper ends with conclusions on the scope for co-produced landslide risk management, including a reflection on the role of academia in this approach.

Three dimensions for the analysis of the co-production of landslide risk management: scale, knowledge and power

Research on co-produced landslide risk management is still relatively limited and requiring consolidation. Until recently this has tended not to be conceptualised through a co-production lens, but rather from the perspectives of community-based disaster risk management. Relevant pilot experiences in community-based disaster risk management across the Global South in the literature go beyond the specific issue of landslides, covering other risks low-income communities are faced with. Examples range from the von Kotze and Holloway (Citation1996) training manual intended as a resource to strengthen the capacities of vulnerable communities to deal with emergencies such as those caused by drought, epidemics, floods and population, to Wisner et al.’s (Citation2003, p. 85) list of ‘key pilot projects that show how lay people in citizen-based groups are capable of participating in environmental assessments that involve technology not previously accessible to them, such as geographical information systems’.

A number of community-based disaster risk management research projects focused on identifying vulnerabilities across communities in Latin America, exploring strategies for communities to use their local resources for risk monitoring and mitigation, have based their approach on the Pressure and Release Model (PAR) of disasters. First introduced in 1994 (Wisner et al. Citation2003), PAR is particularly useful for community-based self-study and monitoring of both vulnerability and capability. In order to understand disasters, the PAR model argues that we need to ‘trace the connections that link the impact of a hazard on people with a series of social factors and processes that generate vulnerability’ (Wisner et al. Citation2003, p. 52). The PAR model, therefore, links the root causes of vulnerability, which may be distant in time and space and ‘invisible’, through a range of dynamic pressures, to the unsafe conditions experienced by vulnerable populations (Wisner et al. Citation2003). A key issue is therefore the different scales at which root causes, dynamic pressures and unsafe conditions operate and manifest. PAR provides a way to understand the context-specific explanation for why, as also noted by Maskrey (Citation2011), low-income settlers living in informal settlements within risk-prone areas will be the most vulnerable within a society. It also highlights three mutually reinforcing factors affecting people’s vulnerability (Wisner et al. Citation2003): insecure and unrewarding livelihoods and resources; low government priority given to the economically and politically marginal; and loss of people’s trust in their own methods for self-protection and confidence in their own local knowledge. Faced with these pressures, as Wamsler (Citation2007) found, households develop ‘coping strategies’ to reduce risk which are diverse and include physical/technological, environmental, economic, social/cultural, organisational and institutional measures (Wamsler Citation2007).

However, the research also highlights that householdcoping strategies and community-based disaster risk management are essential, but not enough. The literature reflects on the need to improve governance structures to develop trust between communities and government organisations, in order to reduce vulnerability, which requires agencies and communities to understand risks. In general, there is a perception that low-income communities do not have accurate information or technical knowledge to respond and mitigate these risks and therefore, solutions have tended to be related with raising awareness and increasing access to detailed information (UNISDR Citation2010). However, understanding how different (vulnerable) communities perceive risk and develop local, low-cost monitoring and mitigation techniques is only a starting point. The challenge is in bringing these concepts together at a practical level rooted in communityempowerment (Maskrey Citation2011). A dominant factor in the literature review of community-based disaster risk mitigation is the critical (but mostly missing) role that the local government could play as a leading actor in vulnerable areas, as well as the role that NGOs and extra-governmental institutions can play as both champions and leaders (von Kotze and Holloway Citation1996; Geilfus Citation1997; Maskrey Citation2011; Anderson and Holcombe Citation2013; among others). A key question that emerges is how can these different authorities and other stakeholders come together to aid communities and collectively negotiate risk management, bringing to bear their different forms and levels of power.

Addressing the question of how to engage a wider range of stakeholders beyond the community, evolving towards forms of what is now described as ‘co-production’, has been linked to the development of thinking around urban resilience and adaptation to climate change. Across Latin America and the Caribbean, several projects and initiatives are noteworthy. The ‘Management of Slope Stability in Communities (MoSSaiC)’ project (Anderson and Holcombe, Citation2006; Anderson and Holcombe Citation2013) generated an integrated method for managing slopes in informal vulnerable areas exposed to landslide risk in the Eastern Caribbean islands through practical and community-led measures. It brought together government agencies, politicians and residents and contractors (based in the community) coordinating efforts to understand and mitigate local landslide hazards through improved surface water management. The community had authorship in developing landslide risk strategies, changing their perception of their potential involvement in hazard mitigation (Anderson and Holcombe Citation2013). The ‘Clima sin riesgo’ project in Lima, Perú, found that low-income urban residents get caught in ‘risk traps’, which are defined as ‘the sum of the articulation and reproduction of vulnerability and daily and episodic dangers or threats, coupled with eroded capacity to act’ (Allen et al. Citation2017, p. 479). In order to address this, Allen et al. (Citation2017, p. 498–499) identified ‘the need for public policies and programmes to acknowledge the piecemeal local investments made individually and collectively, and to build on existing local capacities to support risk reduction and prevention interventions in the long term’. This included involving local communities in the production, management and control of detailed risk data, as a full partner with government agencies.

Fraser’s (Citation2017) analysis of risk management measures in landslide-prone communities in informal urban settlements in Bogotá, as part of the pioneering ladera (hillslopes) programme, highlighted the challenge of moving on from technocratic approaches to include the social and structural drivers of risk, as well as the need to better understand context-specific, politically contingent definitions of risk and the influence of informality on the implementation of risk governance. Analysing one of the case studies in Bogotá’s ladera programme, Meneses and Cañadas (Citation2018) highlight the role of a community-based, technical organisation (Mesa Técnica de Altos de la Estancia - MTA), formed in the wake of a landslide, which united community, institutional and political actors in new ways in order to address and implement risk management strategies. This was key for rapidly scaling up actions from the local to the urban scale in order to integrate this neighbourhood as a functional urban area. Institutional strengthening for risk management in the city of Bogotá, the development of established communication channels between actors at the community and city level, and community empowerment were key aspects of this experience, with community members taking on entrepreneurial roles offering risk-reduction measures as a public service (Meneses and Cañadas 2018). The work of Stein et al. (Citation2018) on ‘Asset Planning for Climate Change Adaptation in Poor Neighborhoods of Tegucigalpa, Honduras’, showed how ‘bottom-up’ community asset adaptation plans could be dovetailed with ‘top-down’ strategic and operational planning. Residents from two urban poor neighbourhoods worked with the Municipality of Tegucigalpa and other stakeholders to co-produce climate change adaptation solutions that encompassed from water harvesting to slope stabilisation against landslides.

In this developing body of knowledge around co-production of disaster risk management and urban resilience, the three dimensions of scale, knowledge and power identified in earlier literature in community-based disaster risk management remain central. They provide a framework for the analysis of such emerging co-production approaches, with the following considerations:

Scale: Expansion of actions from the local scale to structural issues on a greater scale (e.g. that of a watershed) beyond the reach of local actors may achieve a greater degree of risk reduction (Maskrey Citation2011). Recent studies have shown the value in connecting bottom-up strategies for resilience at the neighbourhood scale with more conventional top-down, city-led initiatives (Petcou and Petrescu Citation2015; Stevenson and Petrescu Citation2016).

Knowledge: Building urban resilience requires solutions that are designed and implemented based on available knowledge. Complex problems represent opportunities for solutions to be co-created by a range of relevant stakeholders, based on multi-faceted knowledge sharing, towards building short- and long-term capacity to maintain or rapidly return to the desired functions of the city in the face of a disturbance (Aguilar-Barajas et al. Citation2019). This approach, where stakeholders bring a diverse range of skills and knowledge based on lived and professional experience, bridges the gap between those who produce the built environment and those who use it (Stevenson and Petrescu Citation2016; Allen et al. Citation2017).

Power: Building urban resilience is a contested process, where various stakeholders may clash in terms of motivation and power dynamics (Meerow et al. Citation2016) and diverse social, economic, institutional and political dimensions must be considered (Aguilar-Barajas et al. Citation2019). According to Meerow et al. (Citation2016, p. 46), ‘urban resilience is shaped by who defines the agenda, whose resilience is prioritised and who benefits or loses as a result’.

It is notable that in a number of the experiences described above there were significant overlaps between disaster risk management and urban services, sometimes linked to vulnerability (such as in Allen et al. Citation2017) and in other instances linked to exposure, e.g. due to poor stormwater management (e.g. Anderson and Holcombe Citation2013). However, the fast-growing literature on co-production of urban services and the more limited research on co-production of disaster risk management tend to remain separate, with rare encounters such as through some studies of urban resilience. We contend that the interconnection between urban services and disaster risk management offers scope for further exploration of and reflection on co-production of disaster risk management.

In doing so, however, we need to bear in mind two key differences between urban service provision and disaster risk management:

Firstly, landslide risk management (as is the case for the management of other risks such as flooding, etc.) is not generally perceived as a ‘service’ that is offered to households. In many places, it has only become a responsibility of local government in recent decades and years. Disaster risk management requires a multidisciplinary approach involving partnerships between different stakeholders. However, in many countries in the Global South, it remains (or has remained until recently) a central government function. The trend towards decentralisation is facilitating the increasing involvement of local government (Malalgoda et al. Citation2010) – an involvement that has been advocated by UNISDR (Citation2010). In addition, though there is a movement towards prevention and management, generally there is still a predominant focus on post-disaster attention.

Secondly, as ‘services’ which can be commodified, there is an incentive for providers to offer urban services at a price – from government agencies, through utility companies, to ‘informal’ providers. This is not the case for landslide risk management, which in principle appears to be difficult to assign a cost to – and therefore a price. This is not to say that urban services should be conseptualised as a private good, but we need to recognise that in practice many urban services are, by both the formal and the informal sectors.

So what parallels can we see between co-production of urban services and of disaster risk management through the lens of these three dimensions? Referring to urban services, Mitlin and Bartlett (Citation2018) noted that ‘little attention has been given to the scale of co-production and the way this can change relational possibilities’ (p. 360), even though scale ‘is critical to the transformative potential of co-production’ (Mitlin and Bartlett Citation2018, p. 365). For them, the achievement of far-reaching change at scales beyond that of individual interventions – to city-wide and beyond – is linked to the depth of engagement between community groups and the state. In addition, ‘co-production at [the] local scale takes place in a constrained context where broader issues of redistribution and regulatory reform are excluded by design’ (Mitlin and Bartlett Citation2018, p. 365)

Mitlin and Bartlett (Citation2018) highlight the two-way relationship between knowledge co-production as both an outcome of, and a contributor to, the more general process of co-production of urban services. Social movement leaders and activists operate within this relationship, blending knowledge creation with social action. This puts citizens ‘at the intersection between knowledge production and policy formulation’ (Castán Broto and Neves Alves Citation2018, p. 370), with alternative ways of knowing the city being brought together. The challenge here is how to include in the process types of knowledge that are so different in nature, with their own systems of creation and validation. Knowledge is therefore inextricably linked with power, with information being a pre-requisite for communities to be able to shape their strategies (Chitekwe-Biti Citation2018). Researchers involved in knowledge co-production processes are faced with the challenge of avoiding the imposition of a particular perspective by one of the disciplines or social actors involved (Pohl et al. Citation2010).

In relation to power, many analyses of examples of co-production move from the consideration of co-production as a means for often marginalised communities to achieve essential services, to a means of altering existing relationships between actors and modifying ongoing practices, empowering communities with the notion of urban citizenship (Mitlin and Bartlett Citation2018). In these examples, the services themselves become secondary to the redressing of power imbalances and antagonisms (Mitlin and Bartlett Citation2018). As Mitlin (Citation2008, p. 357) noted: ‘Co-production is attractive to movements both because it strengthens local organizations and because it equips these groups with an understanding of the changes in state delivery practices that are required if they are to address citizen needs’.

The projects this paper reports on focused on landslide risk management, but quickly identified the management of surface water, drainage and sewerage as key relevant issues. The action-research process undertaken in these projects brought together local government agencies dealing with disaster risk management and urban services, and offered an opportunity to reflect on co-production of both. In addition, it provided an exploration of resilience at the neighbourhood scale, which has traditionally been overlooked in favour of measures at the scale of individual homes or larger areas, such as cities (Stevenson and Petrescu Citation2016). In the case of the co-production of landslide risk management as explored in this paper, we will apply the three dimensions set out above at the local level, with scale referring to different scales of intervention (i.e. mitigation-related works) within and around the neighbourhood; knowledge referring to that of the different stakeholders involved, from community, through NGOs, to local government and academia; and power referring to the capacity to influence decisions from neighbourhood to municipal level (which is also related to scale).

Before applying such analysis, the paper next introduces and describes the landslide risk management action-research projects undertaken in Medellin and Sao Paulo ADD accents in ‘Medellín’ and ‘São Paulo’.

An overview of the action-research on co-produced landslide risk management in Medellín and São Paulo: context and methodology

The projects this paper analyses were developed in Medellín and São Paulo. URBAM & Harvard Design School (Citation2012) estimated there were 44,600 households in informal settlements at risk of landslides in the Medellín Metropolitan Area, rising by 13,000 more by 2013. According to the Instituto de Pesquisas Tecnológicas (IPT), 29,000 households live in high-risk areas in São Paulo.

In Medellín, a great number of these households at risk are concentrated on the upper reaches of the NE sector of the city, where the two districts that the project worked in are located – Comuna 1 and Comuna 8 (each with approx. 130,000 inhabitants). These areas have steep slopes with medium-high risk of mass movement due to their geology, topography, ravines and unplanned construction (Katíos, SIMPAD and Environment Citation2012). Settlements here are characterised by unplanned, informal construction, with precarious materials and lack of public services, increasing exposure to risks. This is accentuated by construction over natural streams, which increases the recurrence of these land movements on slopes (CISP and Mayor’s Office of Medellín Citation2015, p. 39). In São Paulo, both informal settlements and landslide hazards are more widely spread throughout the metropolis, but the issues faced are similar to those in Medellín.

The projects analysed here were undertaken in three self-built neighbourhoods in North-East Medellín and one in São Paulo (see ). For all three neighbourhoods in Medellín – Pinares de Oriente, El Pacífico and Carpinelo 2 – the city’s land-use plan (POT 2014) proposes a Programme of Urbanisation, Legalisation and Regularisation as well as an Integrated Neighbourhood Improvement project. However, a significant amount of houses in all three neighbourhoods are located in areas which are classified as high risk and not recoverable, along high voltage lines or in areas for planned infrastructure projects (Alcaldía de Medellín Citation2013, Art. 231). In São Paulo, Vila Nova Esperança is surrounded by a protected forest and has been part of a process of land regularisation, which in principle is not applicable to high and very high-risk areas unless mitigation works are carried out. The community leader was keen for their community to be involved in this research, in order to reduce the risk in the high-risk areas so that they could be included in the land regularisation.

Table 1. Characteristics of the neighbourhoods involved in the action-research.

The research started with a pilot project in Pinares de Oriente, Medellín, which took place from October 2016 to October 2017. The project was co-designed by members of the academic team in the UK and Colombia and a community leader from the NE sector of Medellín. This initial pilot project had as objectives: (1) explore perceptions and narratives of landslide risk in informal settlements within the community and among public sector agencies; (2) pilot and test informal settlement community-managed risk monitoring and mitigation techniques, as is explained below; and (3) collaboratively identify mechanisms to develop a sustainable process of landslide risk-mitigation strategy-building, involving community, government bodies and NGOs (this process of ‘agreement-seeking’ was identified using the Spanish term concertación – see below).

The initial pilot project led to a follow-on project (September 2017 – May 2019) which applied the same methodology – though improved on the basis of the lessons from the pilot project – in two further neighbourhoods in Medellín, and one in São Paulo. In Medellín, the follow-on project took place in one neighbourhood within the same district as the pilot project (El Pacífico, Comuna 8) and one in a different district (Carpinelo 2, Comuna 1), in order to take into consideration different socio-political histories within the city’s NE sector. The follow-on project also tested the transnational transfer of community-based landslide risk management to a different national context within Latin America, by conducting similar fieldwork in one selected informal settlement in São Paulo (Vila Nova Esperança).

The research took a transdisciplinary approach, which recognises the superposition of realities and tries to confront them, focusing on complexity (Smith and Jenkins Citation2015). This approach: (1) tackles complexity in science and knowledge fragmentation; (2) accepts local context & uncertainty, thus becoming a context-specific negotiation of knowledge; (3) implies intercommunicative action, with continuous collaboration between research and practice; and (4) is action-oriented (Lawrence and Després Citation2004). Social science, engineering and environmental science were threaded through the research objectives. The cross-disciplinary teams in each country worked together, taking responsibility for discipline-specific activity but interacting with activities in other disciplines. In addition, in Colombia a community leader was part of the research team, participating in and contributing to all project activity in both countries.

The action-orientation aspect of trans-disciplinarity was ensured through using a participatory action-research methodology. In particular, the projects analysed here are located within the tradition of participatory action-research developed within community development, particularly in the Global South (see, e.g. Chambers Citation1993, Citation1994). This is characterised by shared ownership of research projects, community-based analysis of social problems, and an orientation towards community action (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Our research applied the key principles of participatory methodology as outlined by Moser and Stein (Citation2011): learning from local people and being flexible in the use of methods; learning rapidly and progressively rather than using a blueprint; triangulating information; facilitating rather than doing; sharing information so that it is owned by all participants; and shifting from verbal to visual techniques, from individual to group research and from measuring to comparing information.

In all four neighbourhoods, the officially recognised community association (Junta de Acción Comunal – JAC/Community Action Board in Medellín; Associação de Moradores/Residents’ Association in São Paulo) agreed to participate in the research and to involve the residents. In Medellín, two district-wide Community Boards (those for Housing and Internally Displaced), and local NGOs working in El Pacífico and Carpinelo 2 also engaged in the research process. The strength of these community organisations is the result of decades of interaction between central and local government and the low-income communities in NE Medellín (Dapena Rivera Citation2006). In São Paulo the local branch of the international NGO Teto, which was working in Vila Nova Esperança, facilitated the Brazilian research team’s engagement with the community. In Medellín, the three neighbourhoods are in a part of the city where the ‘territory’ is ultimately controlled by armed groups, which made the relationship of the research team and the community organisations particularly important to ensure the safety of the researchers and the success of the project.

The research objectives were met through the development of four components with their respective research methods. The research methods for components 1 (perceptions and narratives) and 2 (community-based monitoring) are summarised in . This paper focuses on components 3 (community-managed mitigation) and 4 (agreement-seeking and strategy building), the methods for which are explained in some detail as follows:

Table 2. Summary of action-research methodology for components 1 and 2.

Community-managed mitigation of landslide risks: The methodology varied from the first pilot project (Pinares, 2016/17) to the follow-on project (Pacífico, Carpinelo 2 and Vila Nova Esperança 2017/18), and between the projects in Medellín and São Paulo. In all of them, the early stages of the co-production of community-managed mitigation of landslide risks were linked to the methods used for the preceding two objectives. The interviews included sections on mitigation of landslide risk, and the transect walks and participatory mapping identified both existing mitigation works (whether municipal, neighbourhood-driven through participatory budgeting, or individually built) and potential future mitigation works. Desk-top studies by the research team identified officially planned mitigation works, linked to the municipal risk studies of the neighbourhoods. Students and NGO members produced drawn surveys of the neighbourhoods, for which there was very little planimetric and other graphic and construction information available. In Pacífico and Carpinelo 2, this was supported through the use of drone photography by the research team. These inputs and potential mitigation works were discussed in a series of workshops and meetings between the research team and community representatives. In doing so, and as expected in a participatory action-research process, the research team had to operate with flexibility, responding to other ongoing community processes in each of the neighbourhoods. In the four neighbourhoods, improved surface water and wastewater management were identified as a key contributor to decreasing landslide risk. In the pilot project in Pinares, mitigation works were undertaken using low-technology building materials (appropriate for self-build) installed to the technical specifications produced by the research team. Materials were provided by the project, coordination and technical assistance by a local builder and labour by the community. In the follow-on project (Pacífico, Carpinelo 2 and Vila Nova Esperança) the focus was on producing a mitigation works plan for the neighbourhood, so as to coordinate different levels of mitigation works beyond the lifetime of the research project. In the Medellín neighbourhoods, at the end of the process, there was a community evaluation workshop facilitated by the research team.

Collaborative identification of mechanisms for risk-mitigation strategy-building (‘agreement-seeking’ or concertación): In the pilot project this objective was to be met through joint community/public sector/third sector workshops at the end. The findings related to the previous objectives would inform discussion to facilitate agreement and joint action between the stakeholders involved in risk management and mitigation strategy-building and implementation at different scales. However, again adopting the flexible approach inherent in participatory action-research, the research team developed a more nuanced and multistranded approach which responded both to changes in its relationship with other stakeholders and to its own reflections on the process. Two joint workshops were held involving community members, the research team and public agencies in one, and NGOs in the other. The workshop with public agencies took place in the community hall of Pinares, and included a visit to the monitoring points and community-built mitigation works, as well as the presentation of the experience by the community (which they had prepared in a prior session including role play), with the research team acting simply as facilitators. This was the culmination of a wider process that was replicated in the follow-on project, and which involved gradually building the foundations for discussion and possible concertación from the beginning of the project through separate meetings between the research team and community leaders, on the one hand, and the research team and public agencies, on the other. In Medellín, the research team convened meetings between the Local Administration Board (Junta Administradora Local – see below) and the Community Boards for Housing and Internally Displaced of Comuna 8, resulting in the celebration of a large public meeting (Cabildo Abierto). In São Paulo, the research team facilitated meetings between the Housing Development Company (CDHU) and the community leaders – attended also by NGOs Teto and Gaspar Garcia – as well as two large workshops involving a wide range of public agencies, where the project was presented by the community leader from Vila Nova Esperança. These processes are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

The research showed that with training and support from a multidisciplinary team of researchers, and the use of mobile phone technology to report hazard indicators, a willing low-income community is capable of bottom-up participatory monitoring of landslide risks and the implementation of emergency low-cost mitigation works using appropriate technology. The research also showed that this enhanced the communities’ understanding of landslide risk in their neighbourhoods and empowered them in taking forward community-led actions in response to identified hazards, and that relevant local government bodies are willing to engage with this process.

The results on perception and monitoring are discussed in Smith, et.al. Citation2020a], and an analysis of the ‘agreement-seeking’ process in the initial pilot project from the perspective of participatory governance is provided in Smith, et.al Citation2020b . In the following sections, this paper focuses on the co-production of landslide risk-mitigation techniques and strategy-building components of these projects focusing, in turn, on scale, power and knowledge.

Scales of intervention at the neighbourhood level in the two cities

The pilot project in Pinares de Oriente piloted community self-managed techniques for the mitigation of landslide risks in self-built neighbourhoods, which can be developed on a broader scale through community-based researchers and trainers. Unplanned land occupation and development does not necessarily take into account natural and anthropic hazards, among which is the possibility of landslides at various scales. To tackle this, the meetings and workshops between community members and the research team helped identify appropriate and low-cost works to be carried out by residents with technical guidance to reduce this risk. This was proposed as an emergency measure to deal with the situation in the short term.

The research sought to build on the experience and knowledge from earlier comprehensive and incremental settlement upgrading programmes. The approach was based on two main components: a technical analysis of the most vulnerable areas in the neighbourhood, and the establishment of action strategies that could be taken forward through community collaboration and intervention. The approach was based on the mitigation of small-scale ground movements within the neighbourhood, rather than on large-scale landslides that would require larger engineering works.

The analysis of the settlement showed that it is a cluster of houses with very poor roof structures and almost total lack of gutters and downpipes, so a significant amount of water ends up being poured onto and absorbed by the ground, as internal courtyards with hard floors and drains are also very scarce. This contributes to a weakening of the load-bearing capacity of the soil and to an increase in the likelihood of landslides. On the other hand, the way in which the settlement was generated initially by individual houses and its gradual but dispersed consolidation, disorganised and lacking in an overall plan, has generated a series of residual spaces, with little accessibility, next to the slopes. These spaces serve as a separation between the dwellings and are areas where there is dampness and, therefore, are a source of conflict between neighbours. These areas also generate erratic and uncontrolled water flows, which heighten the risk of landslide due to the widespread presence of exposed slopes without treatment or protection. The analysis also identified more structural control and protection measures to be addressed through other mitigation measures at a larger scale and involving public institutions.

Four levels of water management were identified, from which a spatially organised proposal was made to establish a community network structure for the mitigation of landslide risk, comprised of the following elements:

Primary network for conducting surface water: Large existing public network of underground pipes under the main access roads and under the responsibility of local authorities in collaboration with public companies.

Secondary public drainage network: Located within the neighbourhood, these drains can be underground or exposed, generally located along access roads, stairways and footpaths. These secondary drains are the responsibility of the local authority.

Tertiary drainage network in residual areas: These are usually found at the back of the houses and in semi-private places that are the result of the location of accesses between groups of houses. These are the responsibility of the owners of the adjacent homes.

Fourth level in individual houses: This level considers interventions in gutters and downpipes in private homes.

The research team and the JAC jointly decided that the focus should be on the tertiary and secondary drainage networks, as these were within the scope of what the community could address collectively. The primary network required technical input and material resources that were beyond the capacity of the community, and the fourth level was a household responsibility. A number of interventions were also carried out in individual dwellings, generally in the case of houses that affect others, always seeking to benefit the neighbourhood rather than specific individuals.

Community-led work, using a small budget for materials that the initial project had, was based on traditional ‘receptions’ (convites) or community events whereby volunteers gathered on a weekend day and took part in the work, followed by a joint meal. The construction was led by the consultant architect for the project, and guided and coordinated by a local builder. As a result, the conduction of rainwater and the safety along spaces and footpaths in the community were improved, as well as the rainwater drainage systems in some individual houses, with these works as a whole affecting approximately thirty dwellings. Following the implementation of the works, residents noticed differences in the way in which the soil is affected by rainfall and changes in the level of soil moisture. The project provided learning for both the community and the municipal government organisations to whom the mitigation works were shown, on the importance of community action strategies.

In the follow-on project in two further communities in Medellín and one in São Paulo, work on mitigation was approached in a more strategic way with a long-term view, setting out a plan for landslide risk mitigation for each community which identified what needed to be done and at what scale. This necessitated a more in-depth analysis of the scales of intervention in the neighbourhood.

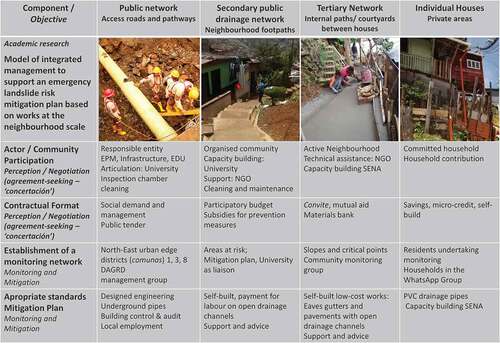

In Medellín, further development of the research team’s understanding of the different scales led to seeing landslide risk mitigation in connection with drainage, and in turn in connection with pedestrian (and in parts limited vehicular) circulation through the neighbourhood. It became increasingly clear that landslide risk management at the neighbourhood level was intrinsically linked with the urban infrastructure, and therefore with scope for co-production as is the case with urban services. The initial list of four levels developed into the matrix shown in .

Figure 1. Model of integrated management to support an emergency landslide risk-mitigation plan based on works at the neighbourhood and household scales. (Acronyms: DAGRD (Departamento Administrativo de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres – Administrative Department for Disaster Risk Management); EDU (Empresa de Desarrollo Urban – Urban Development Company); EPM (Empresas Públicas de Medellín – Medellín Public Companies); SENA (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje – National Learning Service). Source: Medellín research team.

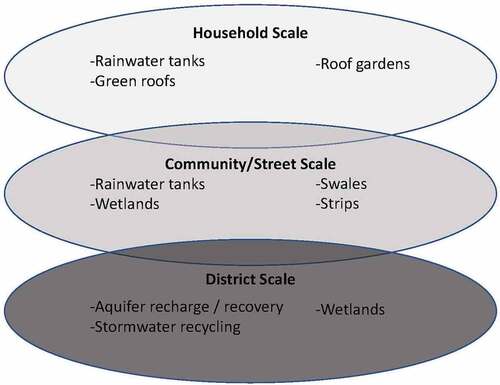

The research team in São Paulo, responding to different site conditions and taking a broader look at how to respond to a range of hazards affecting the neighbourhood they worked with, produced an overview of the different scales at which such hazards could be addressed according to hazard type, as shown in .

Figure 2. Hazards, agents and their potential involvement in mitigation. Source: São Paulo research team.

The model developed in São Paulo to address risk mitigation separated stormwater management from slope stability because of the specific nature of the landslide hazard in the neighbourhood of Vila Nova Esperança. In Medellín, all three neighbourhoods involved in the research were grappling with the issue of water running through the settlement and threatening small-scale landslides affecting from individual to small groups of houses (plus specific issues around potential rockfalls, etc.), whereas in Vila Nova Esperança, the landslide threat was specifically linked to construction on the edge of, and below, a steep escarpment and on a non-compacted land infill. This required mitigation works at the level of the groups of houses on such land as a minimum, with little scope for effective action at the household level.

However, both diagrams show parallels with research into the co-production of stormwater management, including Yu et al.’s (Citation2011) exploration of decentralised water systems at various scales in Australia, as shown in . This distinguishes three types of decentralised system based on size: on-site, serving one or two plots or households; communal systems serving from two to possibly 2000 or more plots; and district systems serving 5000–20,000 plots. In Australia, on-site systems are typically privately owned and managed, communal systems may be privately owned and managed, and district systems are predominantly owned and operated by local or state government agencies.

Figure 3. Decentralised water systems at various scales. Adapted from: .Yu et al. (Citation2011)

The conceptualisation of scales of intervention developed in this action-research, as shown in , stops at the level of the neighbourhood, as these projects were addressing the risk of small landslides within neighbourhoods, but can be developed further upwards to encompass wider geographic scales such as hydrological basins or entire hillside (specifically relevant in Medellín) and/or administrative scales such as district, city or metropolitan area. Conceptualising and visualising these different scales, whether directly in relation to landslide management or in relation to urban services that impinge on landslide risk, such as stormwater drainage, can help identify appropriate roles for the different agents that may become involved in co-produced landslide risk management – from households to government agencies. How these roles are negotiated and become articulated depends on power and power relationships, as is analysed next.

Levels of power and their links to scales of intervention

We consider power here as ‘the capacity of social actors to influence decisions’ (Brugnach et al. Citation2017, p. 21). Power is therefore analysed as referring to social relations, including what has been termed ‘power to’ and ‘power over’, as argued by Pansardi (Citation2012). And we start by understanding the basis for the social relations among the key actors involved.

The conceptualisation of scales of intervention in order to identify roles in an approach to landslide risk management based on co-production assumes willingness on the part of the different agents to engage in such roles. However, the context in which the action-research started in both cities was one of confrontation and/or lack of co-operation between the communities and local/state government agencies. Acceptance of these roles and development of ways of working conducive towards co-production, therefore, required a process which at the outset of the initial pilot project in Medellín was labelled ‘negotiation’, a term that was soon replaced by the Spanish term concertación, which can be translated as ‘agreement-seeking’ (which is not necessarily ‘consensus-building’, as each party may retain their own view and agenda rather than converging to a consensual agenda).

In Medellín, the confrontation between community and local government affected the entire NE area of the city, with different levels of mobilisation across the different districts (comunas) of this area In relation to self-built neighbourhoods, the official response to the threat of landslides in Medellín has been mostly proposed in strategies and interventions based on evacuation, stabilisation, relocation and redirection. Despite the awareness of risk fostered by previous and ongoing landslide events and the City Administration’s arguments to relocate parts of informal settlements based on geological studies, the residents of the upper parts of this area of Medellín resisted relocation and protested that the local government had other motives. Such confrontations were based on a mix of factors including fear of removal from existing social networks and livelihood sources; distrust of officialdom, fuelled by a perception of double-standards regarding ‘formal’ buildings allowed on the slopes; priority given to other demands for infrastructure and services; and possibly the influence of armed groups involved in informal land allocation.

These proposed official strategies assume shared rationalities among public sector agencies and the affected communities, as well as shared agendas in relation to these communities’ welfare. In addition, the relocation of communities tends to be very slow, with new housing programmes taking too long or being unable to cope with the numbers of people located in these vulnerable areas. However, risk-reduction strategies are being implemented in partial ways which to date show limited success. For example, a linear park was designed along the north-east edge of Medellín to provide a green boundary to urban sprawl up the mountainside, but this was only partially completed and unable to achieve its objective, thus generating further distrust between communities and government institutions.

São Paulo, with its high proportion of informal settlements and also homeless population, is the site of much community and social mobilisation around the issue of shelter. Against this background, after two unsuccessful attempts to work with communities in different parts of the city (see next section), the São Paulo research team worked with a community that has a particular history of confrontation with government agencies. In 2009 the largest landowner in Vila Nova Esperança – the Housing and Urban Development Company of the State of São Paulo (Companhia de Desenvolvimento Habitacional e Urbano, CDHU) – initiated legal action to evict the residents and create a park, which resulted in a tense relationship between the state organisation and the community, including armed threats to the latter. On the other hand, in response to (NGO-supported) community lobbying, the revised land-use plans in the two municipalities this community falls within declared most of the neighbourhood an Area of Special Social Interest (Zona Especial de Interesse Social, ZEIS), which provides residents with a level of legal protection.

Therefore, although with different histories and characteristics, the nature of the community–state relationship initially hindered the development of joint strategies to address landslide risk in these neighbourhoods in a concerted manner. Moreover, it left no room for sufficient consideration of possible actions in the short, medium and long term, and to identify the responsibilities and capacities of the various actors, which could contribute to co-produced risk management strategies that could cover the entire at-risk population.

Work towards overcoming this in the participating neighbourhoods in both cities was an essential part of developing pathways towards co-produced landslide risk management, and took place at several levels, starting at the neighbourhood level. In the pilot project in Pinares de Oriente, from the start the research team worked directly with community leaders, who had the convening power to draw in volunteers to take part, first in the participatory landslide risk monitoring and then in the mitigation works. Although these leaders were part of a formally elected and constituted Community Action Board (JAC – the legal figure used by community organisations in Colombia), the personal draw of the president of the JAC was significant in garnering support for the initiative within the neighbourhood. A similar situation was found in Vila Nova Esperança, where there was also a strong and highly active community leader, also president of the residents’ association. Individuals with such power to galvanise community action quickly were very useful for the action-research process, but also a weakness if they left the community – as happened in Pinares de Oriente. In the two follow-on neighbourhoods where the approach was replicated in Medellín (El Pacífico and Carpinelo 2), the research team engaged with JACs where power was more evenly distributed among the community leaders, and which worked together with supporting NGOs (as was the case in Vila Nova Esperança). The latter also had benefits in terms of continuity and spread of the knowledge that was co-created through the process (see next section).

In the case of the pilot project in Pinares de Oriente, the participatory monitoring and community-based mitigation works were evaluated by the community and presented to representatives from relevant local government agencies, which praised the low-cost emergency landslide mitigation works undertaken by the community. This resulted in the establishment of a community-local government working group involving four departments and agencies of the municipality: Planning (Departamento Administrativo de Planeación – DAP), Disaster Risk Management (Departamento Administrativo de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres – DAGRD), Housing (Instituto Social de Vivienda de Medellín – ISVIMED) and the Urban Development Company (Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano – EDU). This working group’s agenda was to look at the possible ways forward for the at-risk area of the settlement once the risk survey plans have been approved, and to analyse the larger interventions required to mitigate risks that were being proposed to see if these could be addressed using municipal resources.

In Vila Nova Esperança, the research team facilitated conversations between the community leaders and CDHU, initially using a wider seminar at which both presented among other speakers, as a ‘neutral’ setting in which ‘agreement-seeking’ (concertação) could be sought in a non-confrontational way. Whereas in Medellín the efforts to bring together community inputs and local government action included a range of municipal agents which could be directly involved in co-producing landslide mitigation works, in São Paulo the key focus was on the state landowner due to the history and circumstances of the neighbourhood, though conversations were also held with the Municipalities of São Paulo and Taboão da Serra and with their respective Civil Defence departments, responsible for disaster risk management.

In Medellín, the process was taken to a further level, that of the district (comuna), by holding large public meetings in 2017 and 2018, each attended by over 600 residents and by local government representatives, on the theme of risk management and integrated neighbourhood improvement. These meetings used the legal figure of the Open Council Meeting (Cabildo Abierto), defined in the Colombian Constitution as a type of meeting where the local government is required to listen to petitions from the community and to respond to them. Organising the first of these required the brokering of an agreement (by a member of the Colombian research team) between the Local Administration Board (Junta Administradora Local – JAL) and the Housing and Internally Displaced Community Boards for Comuna 8. The JAL is the lowest level of local government and has the power to summon local government officials from the municipal level, while the Community Boards (Mesas) are district-wide and issue-specific community organisations that can garner the participation of residents from across the district. Intervention from the member of the research team encouraged these organisations to overcome their differences and to join forces in setting up a process that opened up a dialogue between the community and the municipality at the district level, achieving a distinctly positive change in tone between the first Cabildo in 2017 and the one in 2018.

The power to influence decisions and to implement actions among the actors that have been introduced and described in this section map on to the scales of landslide risk-mitigation interventions shown in . However, this mapping does not follow neatly into place simply by identifying roles and scales that are appropriate to the power of each actor. The action-research process involved working directly, and in some cases with difficulty, on the social relations through which such power is enacted.

Studies of co-production of urban services such as Joshi and Moore (Citation2004) and Moretto (Citation2014) have identified the political attractiveness of institutionalised co-production, as it allows a reduction in the cost to the state in providing such services, while also increasing political support for the government in exchange for some loss of control and power to community and civil society organisations. This attractiveness is not so apparent when it comes to landslide risk management, particularly when this is linked to issues related to safety and to the right to remain on the land, which prompts a stronger urge for control in and by state organisations. This was very apparent during the action-research process, in which reaching a point where landslide risk mitigation works could begin to be seen as a co-produced continuum from household management of on-site stormwater to large land-retaining and drainage infrastructures provided by the government, required a great deal of ‘diplomacy’ and facilitation on the part of the research team. This process required explicit recognition that each actor brought to bear a different level and type of power, but also different types of knowledge, as we examine next.

The interplay of knowledges in facilitating the co-production of landslide risk management

Co-production of landslide risk management requires mutual recognition of the validity of the different types of knowledge and ways of knowing among the actors involved, particularly in physico-social contexts such as the neighbourhoods where this action-research took place. In addition, knowledge is used in combination with value systems, and as a result, even when there is agreement about facts there can be different interpretations of these and views on how to respond to them (Brugnach et al. Citation2017). In the case of Medellín, for example, at the outset, apparent disregard for community knowledge by public authorities was matched by deep suspicion among community residents towards the detailed neighbourhood technical risk assessments commissioned by the municipality, due to their implications both for the prospects of households remaining in their homes and for public investment in the neighbourhood, and the protracted and opaque process of their production and formal approval. An important achievement of the action-research process was that the community involved learnt about landslide risk management through undertaking risk monitoring and mitigation. Dialogue was facilitated among such communities and state actors, as well as held between the academic team and all other actors involved.

In Medellín, this was aided by the fact that community leaders in the NE sector, and particularly in Comuna 8, had been developing a connection with academia, both local and foreign, through the ‘dialogue of knowledges’ (diálogo de saberes) approach. The roots of this approach go back to Paulo Freire’s contributions to pedagogy, particularly community education, based on learning through dialogue and working together (Freire Citation1972), and to the valuing of ‘local’ and ‘indigenous’ knowledge that was the basis for the development of participatory appraisal in the 1990s, which promoted local communities undertaking their own research and subsequent action (Chambers Citation1994). This connection between local communities and academia in Medellín had been developing over the last two decades particularly through the work on the social production of ‘habitat’ undertaken by the Escuela del Hábitat at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

In recent years, community leadership in Medellín’s Comuna 8 not only increasingly includes people with university education and other training but is also more actively seeking engagement with academia, in whom they see both a source of knowledge and an ally in helping the community interpret the technical studies commissioned by the local government. The type of relationship with academia the community leaders foster can be seen as falling within Purcell’s (Citation2013) notion of ‘network of equivalence’, with mutual respect for each other’s knowledge. This worked well particularly in the three neighbourhoods where the action-research took place in Medellín, and with some limitations in the case of São Paulo, as is discussed below.

Characterisation of the types of knowledge involved in this ‘dialogue’ often distinguishes between scientific knowledge held by academia and local or experiential knowledge embodied in local residents’ daily life. Indeed, in the action-research projects analysed here, the research team valued the community’s knowledge of the history of each settlement, the way parts of the neighbourhood are affected by heavy rain, etc., and the community listened to the research team’s technical assessment of key points to monitor and mitigation proposals – and acted upon them. However, the split between ‘technical’ and ‘community’ knowledge is not so clear-cut: community members raised technically valid points when discussing proposed mitigation works, and the research team was very mindful of potentially adverse community dynamics, based on previous experience, when discussing technical solutions and implications.

The particular characteristics of the landslide risk in Vila Nova Esperança, São Paulo, illustrated some limitations to this ‘dialogue of knowledges’ if it is not broadened from community and academia to other actors with other resources (including other types of knowledge). In all neighbourhoods involved in the action-research, and particularly in Medellín, there was a large overlap between short-term landslide risk management and appropriate stormwater management, which within the neighbourhood could be addressed with low-tech and low-cost solutions. This, therefore, required a certain amount of technical knowledge from the academic team and a good deal of organisational and mobilisation knowledge from the communities, and lent itself to co-production in the sense that the communities could provide such infrastructure up to a certain scale, to then be complemented by connecting to a larger scale drainage network supplied by the municipality. However, in Vila Nova Esperança, a substantial amount of the homes deemed to be at risk were located above and below a very steep and unstable incline, which required both engineering intervention to stabilise the slope and social intervention to remove and/or push back homes that had been built close to the edge. This in itself does not negate the potential for co-production, with the community and local government working collaboratively, but because of the past history in this community, which had developed many of its own solutions with little or no state support in the past, there was a perception among the community that they could address the threat at this location on their own. As a result, the research team had to work closely with them to help them understand the technical limitations of the solutions being proposed by the community, as well as the fact that some of these could increase the threat to people’s lives.

An implicit aim in the projects from the beginning was the extension of the ‘dialogue of knowledges’ to encompass further actors beyond the community-academia link, in particular trying to establish stronger understanding between community and local government. This necessitated mutual valuing of their respective knowledge, which was hindered by the conflict-laden relationship between these two actors. In this regard, the projects increased the credibility of the participating communities in the eyes of the relevant local government agencies through two processes. Firstly, the community-based monitoring groups demonstrated that as a community they were able to systematically collect data and, in the follow-on project, analyse the data in a participatory and qualitative way which increased their understanding of the ground conditions and behaviour of rainwater in their neighbourhood. Secondly, the communities were able to propose (and in the pilot project, partially implement) emergency landslide mitigation works based on the above increased understanding of ground conditions and water flows through their neighbourhood, and to explain in a reasoned way what inputs were required from local government. Local government response to this, particularly in Medellín, was to use their knowledge of the administrative process to offer ways to work together towards a form of co-production of landslide risk management, while maintaining the official line about the status of land that had been mapped as being at high risk or beyond the urban area boundary. There was potential for more work towards mutual understanding and lowering of suspicion by explaining the detailed technical risk assessments in Medellín to the community. However, this was not possible at the time because the assessments had not yet been approved officially.

Learning from the experience in the pilot project in Pinares de Oriente, the two follow-on projects in Medellín and the one in São Paulo engaged with NGOs that were already working in the respective neighbourhoods. A key purpose was not only to provide additional support to the communities involved, but also to facilitate continuity and wider community dissemination of the knowledge created by the process. In Medellín, the research team established a partnership with two NGOs that were supporting the communities of El Pacífico and Carpinelo2 – Corporación Montanoa (currently Tejearaña) and Con-Vivamos – as well as with the community organisations themselves. This entailed detailed initial discussions about the relationship between all three types of actors and agreement that the knowledge created during the process would belong to all involved and be acknowledged as such. This agreement has facilitated the inclusion of the knowledge generated by the process in a course on risk management offered to community leaders across the NE sector of the city by the ‘Hillside Neighbourhoods School’ (Escuela de Barrios de Ladera), an initiative of one of the NGOs with academia and community. In São Paulo, the research team engaged with the local branch of the international NGO TETO, which was already involved in supporting the community in Vila Nova Esperança. In both cities, the respective NGOs have continued to work with the communities involved following the end of the funded research projects, thus ensuring continuing support to the process of landslide risk management co-production initiated by such projects.

Conclusions and reflections on academic engagement in co-produced landslide risk management

In addition to the action-research findings on perceptions and narratives, and participatory monitoring of landslide risk – briefly explained earlier – the projects demonstrated that it is possible for communities affected by landslide risk to develop mitigation plans and to implement small-scale emergency mitigation works, which address both rainwater drainage and landslide mitigation, with technical assistance from both government institutions and academia. The experience also helped scope the limits to what action the community was able to undertake and the types of collaboration with other agencies (mainly from local government) that are required to address landslide risk management in a comprehensive way – i.e. the co-production arrangements that would be appropriate.

In both cities, it was possible to identify very similar scales of intervention for landslide risk mitigation in the neighbourhood, linked to the drainage and movement networks, each scale with appropriate and feasible inputs from specific stakeholders, from households up to local or state government. Linked to such scales of intervention are different levels and types of power. Co-production of landslide risk management required careful brokering and facilitation of opportunities for different stakeholders – community organisations and local government agencies in particular – to understand each other’s potential contributions and limitations. In both cities, the action-research process helped reduce the pre-existing levels of confrontation and non-engagement between community and state institutions and facilitate dialogue, with the initial step being the exploration and discussion of perceptions and narratives around risk, which started creating common understandings around the issues and the scope for action.

This dialogue was enabled by mutual recognition of the value of respective sets of knowledge and values. Prior to the creation of mitigation plans (and in the case of Pinares de Oriente, the implementation of emergency low-cost small-scale mitigation works), the establishment of community-based landslide risk monitoring systems with systematic data collection and community analysis of these data, aided constructive community-state engagement by providing the communities with an understanding of their neighbourhood from a landslide risk perspective and with credible evidence which they could use in their interactions with state agencies. It also helped communities meaningfully engage in the creation of landslide mitigation plans for their neighbourhoods, with an understanding of the issues that such plans addressed.

Technology had a role to play particularly in relation to the monitoring and mitigation components of the action-research projects. Community-based monitoring of critical landslide risk points using mobile phone photography helped establish horizontal flows of information within the community, as well as adding to their credibility when dealing with local government. Monitoring was not a process that involved everyone in the community as an active agent, but the knowledge generated by it spread beyond the volunteers who had appropriate mobile phones and the capacity to engage in the process. However, two key issues were: (1) the continuity of the mobile technology-enabled monitoring beyond the timescale of the action-research projects; and (2) concerns over the potential use of the collected data by local government agencies if communities were to pass it on to them on a regular basis as a possible agreed way of co-producing knowledge related to landslide risk. This concern from the communities (and particularly from the NGOs supporting the communities) showed that the initiatives to develop co-produced landslide risk management have not de-politicised the relationship between the communities and the local government (Swyngedouw Citation2010; Kenis Citation2018). The shift of engagement from confrontation to dialogue had not had an effect of co-opting or nullifying political struggles: the demands from the community are still there, as is a certain level of distrust.

Regarding mitigation, the technological considerations were related to the appropriate technologies at each of the identified scales of intervention. The projects confirmed that low-cost ‘appropriate technology’ enabled communities to be the main actor in mitigating landslide risk at the tertiary network (residual spaces) and fourth level (individual house) scales identified earlier. The higher scales (primary and secondary networks) require local government and public agency involvement partly due to the building and engineering technologies required. Acknowledgement of the roles and potential of these different technologies provides a basis for co-production of mitigation works.

The experience, therefore, shows that landslide risk management can indeed be co-produced, but there are three key considerations to be mindful of when comparing with urban services co-production. Firstly, there is less scope to provide landslide risk management as a co-produced paid-for service per se, as might be the case for urban services, and therefore it is not amenable to being provided by non-formal private actors (as, e.g. water is), but it can be a shared responsibility between community and government. Secondly, there are limits to what the community can do in terms of scale and technical knowledge required, which is also the case for urban services to an extent. Thirdly, going back to the PAR model, both exposure to landslide hazards through lack of land for housing elsewhere and household vulnerability because of poor access to urban services are linked to the same ‘root causes’. As the research showed, most of the population in these neighbourhoods had arrived driven by conflict (in Medellín) and by low-income combined with a search for better living conditions (in São Paulo). National socio-economic inequalities and conflict were at the root of their current unsafe conditions, and addressing these requires actions at a much higher scale, which are beyond the scope of what projects at the local level such as the ones analysed here can achieve.

However, the experience of these projects and consideration of the above limitations suggest that, at the local level, much more could be achieved to address landslide risk in self-built neighbourhoods through the following: (1) landslide risk management should be built into overall neighbourhood upgrading and management programmes and projects, thus optimising the benefits resulting from service provision in relation to risk reduction; and (2) if anything, the state should intervene more in these areas in order to implement mitigation works that require its resource mobilisation power and technical knowledge, in partnership with the community. These two corollaries imply that co-produced landslide risk management is not simply about dividing up different scales of action among community and government organisations, but giving the affected communities an effective say in decision-making and technical assistance to develop long-term landslide risk-mitigation plans – and mechanisms for this differ from country to country and from city to city.

Finally, the action-research process was led by academic teams, bringing together knowledge drawn from universities in the Global South (in the case study cities) and the Global North, while at the same time learning from the other stakeholders and from the process as it unfolded. The ultimate aim of the projects was to co-create systems which would enable community and relevant state organisations to manage landslide risk jointly, without ongoing external input from academia. However, the success of the projects led other community organisations in Medellín to request that the academic team replicate the experience in their own neighbourhood. In this city, there is clearly a demand from mobilised communities to involve academia in their endeavour to become integrated into the city and protected from hazards, which is not necessarily the case in other cities. This leads us to two final reflections on the role of academia in enabling the coproduction of landslide risk management in the Global South: (1) academia has great potential to help communities and local governments develop a co-production approach in a field that has not lent itself in recent times to such an approach to the extent it has in relation to urban services; and (2) academia’s potential role varies greatly with context, from places where the demand for its input exceeds its capacity even though there are strong academic institutions, through places where academia is regarded with suspicion and its input rejected, to places where academia is too weak or even inexistent. This reinforces the importance of other stakeholders such as locally committed NGOs, and their role in co-producing and disseminating knowledge at the community level, such as through the ‘Hillside Neighbourhoods School’. Co-production and co-management of relevant knowledge are therefore key elements of the co-production of landslide risk management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguilar-Barajas I, Sisto NP, Ramirez AI, Magaña-Rueda V. 2019. Building urban resilience and knowledge co-production in the face of weather hazards: flash floods in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area (Mexico). Environ Sci Policy. 99:37–47. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2019.05.021.

- Alcaldía de Medellín. 2013. Formulación de determinantes del modelo de ocupación [Development of criteria for land use model]. Departamento Administrativo de Planeación Convenio No 46000048673. Spanish.

- Allen A. 2012. Water provision for and by the peri-urban poor: public-community partnerships or citizens co-production? In: Vojnovic I, editor. Sustainability: a global urban context. East Lansig: Michigan University Press; p. 209–340.

- Allen A, Griffin L, Johnson C. 2017. Environmental justice and urban resilience in the global south. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Anderson MG, Holcombe EA. 2013. Community-based landslide risk reduction: managing disasters in small steps. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Anderson M, Holcombe L 2006. Purpose-driven public sector 1580 reform: the need for within- government capacity build for the management of slope stability in communities in the Caribbean. Environ Manage. 37(1):15–29. doi:10.1007/s00267-004-0351-z.

- Batley R, Mcloughlin C. 2010. Engagement with non-state service providers in fragile states: reconciling state-building and service delivery. Dev Policy Rev. 28(2):131–154. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7679.2010.00478.x.

- Brugnach M, Craps M, Dewulf A. 2017. Including indigenous peoples in climate change mitigation: addressing issues of scale, knowledge and power. Clim Change. 140(1):19–32. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1280-3.