ABSTRACT

Urban projects are developed partly to solve local problems but often have wider aims to influence policy and practise. However, there is very little long-term evaluation carried out, and few systematic efforts to link the experience gained in project development and implementation to wider learning and capacity building. I have written this opinion piece based on my experience both in practise in the public and private sectors and in teaching and research. The paper is divided into three parts. First, why urban projects and programmes are important for learning and capacity building. Second, how we learn from projects and the opportunities and barriers to learning. Third, how we could increase learning by explicitly including learning objectives in project planning and evaluation, strengthening links between practice and learning, and improving long-term access to project materials with learning potential.

Why urban projects and programmes are important for learning

Capacity to manage urban development well is critically important, especially with the challenges related to climate change. To help build this capacity, urban development projects and programmes, especially those which test new approaches, are a valuable potential source of learning. However, I believe that we learn much less than we could. In this think-piece I use my experience as a practitioner and educator as a lens to explore why knowledge and learning from projects and programmes is limited and often difficult to access. I will also suggest how we can improve the situation.

Urban projects and programmesFootnote1 deal with subjects such as urban upgrading, housing, infrastructure, and climate change resilience. They are the closest thing that we have to objective tests of concepts in urban development. I will concentrate on urban projects, but most of what I write also applies to urban development programmes. Projects can take many forms, but I will focus on those supported by international development organisations as I have first-hand experience and they are normally well documented, at least for internal use. These often have broad objectives to inform policy and practice, in addition to solving local problems. However, the learning is often limited to those directly involved. For learning to be effective it is necessary to be able to access outputs including data and documented lessons and experience which can both inform policy making and input to education and training.

I argue that learning is much more limited than it should be because of the way projects are organised, evaluated, connected to education and training, and communicated. I look first at how we learn from urban projects and programmes, and then what barriers limit learning. I end by proposing how the learning potential can be improved.

How do we learn from urban projects, and what limits us?

I will unpack the process of learning from urban projects by looking at who the target groups should be and what should be available for learning. I then review the sources, channels, and barriers to learning.

Who needs to learn from projects and what do they need?

The main target groups for learning should include key stakeholders in development – the policy makers, practitioners, communities, evaluators, and academics. Policy makers need to be convinced that an approach is going to provide results, so they need to see results and success. Evaluators need indicators to assess how a project met its aims, but they also need to understand roles of key actors and processes. Practitioners want to know how an approach aligns with policy, whether it works, and how to go about using it. Communities want to know how approaches have performed and how to play their roles effectively. Academics and students want to understand objectively what a project is, how successful it was, how it relates to concepts and what lessons can be learned. The groups least likely to be able to access lessons arising from projects are practitioners and communities outside of the project. In general, they cannot access evaluation reports, project reports or academic papers. Even if they could, they would find only limited insight into the roles of key actors and guidance on how to use the lessons.

The sources, channels, and barriers to learning

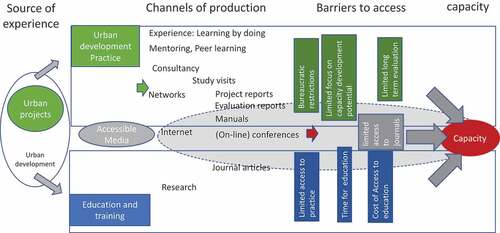

I now look at how knowledge moves from experience gained in a project to capacity being developed. There are three main channels for learning: learning from practice; learning through education and training; and learning through internet-accessible material. These are illustrated in together with some of the main barriers to learning.

Practice

I would like to first look at how we learn from practice. If I look at my own experience, learning by doing is probably the most valuable. The limitation is that only a small number of people can have the experience of being directly involved in innovative projects. Another channel which can reach many more people is Learning by sharing (peer learning). This allows wider access via networks- for example local government associations, professional associations, and includes slum dweller networks. This is powerful because lessons can be learned directly from those experiencing similar situations, so the credibility is higher. The value is further increased if good documentation is available.

Project reports are another resource. Report writing is often seen as the curse of working on projects but reports often contain valuable research and potentially they can provide useful information. These reports are normally aimed at project management rather than for broader communication and learning. Consequently, circulation of reports is restricted by default.

Evaluation reports are prepared for most development projects, but again normally for an internal management audience, though some organisations make these available externally (Asian Development Bank Citation2016).Footnote2 In addition to access there is a problem with timing because they are usually carried out mid-term and at the time of closing a project. However, it is also very important to know how an urban project performs after 10, 20 or even 30 years. Such long-term evaluations are very rare. As an example, I was involved in Ismailia, Egypt, in a series of upgrading and site and service projects. These received considerable national and international attention, but despite this there has never been a formal evaluation.Footnote3 The administrative need to ‘wrap up’ projects make long-term evaluation difficult to manage. Informally, together with colleagues I have used the cases in teaching and encouraged and assisted researchersFootnote4 with some success.

Promotion reports, short glossy reports that highlight success, are often issued when a project is nearing completion. This is an attractive source, as policy makers and practitioners want to associate with success and keep up with the latest trends. However, these reports are often not validated. There is also a strong case for learning from mistakes but normally it takes some time for people to admit that not everything was a success. UN-Habitat has for many years developed and made accessible a database of best practice cases which are useful for inspiration. The reports aim to be validated, but they are limited in operational detail, so fall between a promotion report and the learning reports described below.

Learning reports are those written specifically to communicate lessons from a project, though these are not common. In the Ismailia projects mentioned earlier, we persuaded the donor (UK development aid) to fund the preparation of a manual to provide wider access to lessons from the development process (Davidson and Payne Citation2000). This was published and though it had to be purchased allowed much wider dissemination than is usual.Footnote5 A more recent example, also in Ismailia, was the report on upgrading projects in El Hallous and El Bahatini which complemented the evaluation report (Madbouli and Hassan Citation2011). A further experience was with the community-based training and evaluation projectsFootnote6 in Zambia, where I was commissioned to write learning reports. These used inputs from project documents, evaluations, and interviews, as inputs to communicating key lessons. Learning reports allow writing to communicate lessons widely rather than only to fulfil project tasks. They can also be objective when written by independent reviewers.

Education and training

Education and training are important channels to share learning as they actively work with the products of project experience to enhance learning. They do this in three main ways: providing direct exposure to experience from practice; using case studies and papers and through research.

Direct exposure to practice can come through inputs of staff with field experience, guest lecturers, field visits and sharing with students who come with their own experience.

Case studies based on project materials and additional research are a well-used teaching tool which helps link theory to practise. These are strengthened when there is input from practitioners.

Research provides a very valuable input to learning from projects as it provides objectivity. The outputs in the form of theses and academic publications are very important within the academic system. Access can be difficult and expensive for those in practice, though the situation is improving through ‘open access’ publication. For example, the international Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) is helping access by allowing a good proportion of papers (though not all) in their journal Environment and Urbanisation to be openly accessed. There are also good examples of research being funded by development organisations and being made accessible including OECD and UK development aid funded research in the 90ʹs. These outputs could be considered as learning reports.

Learning via internet

The most common channel of learning today is via ‘googling’, so the quality of what is accessible online is very important. As discussed earlier, urban projects normally include some form of review or evaluation. However, only a limited amount of this information, if any, is available online. I tested this out by checking projects that I have been involved in personally or have evaluated to see whether lessons learned were available. Out of 10 projects reviewed there were only two with publicly accessible material. In one case, it was informal – the practitioners involved actively promoted access and used the cases in teaching and encouraged research. In the second case only a project completion report was available with very limited lessons, and none of the research which had been undertaken. Availability of evaluation reports online varies between development organisations and over time. It is understandable that evaluation reports may include sensitive material, but as a result wider access is often blocked, thus losing the learning potential.

There is good practice in making quality materials based on project experience accessible. UN-Habitat, Cities Alliance, GIZ, ICLEI and development banks provide some good examples, but much more could be done. Learning materials depend on a foundation of good reports, evaluations and research being produced. They also require external validation.

How can we improve the potential learning from urban projects and programmes?

Much of the potential for learning from urban projects and programmes is wasted because either not enough good learning material is generated, or it is not sufficiently accessible. So, how do we improve? I see three main areas. First, building learning into projects, second strengthening the connection between practice and education and third maximising the quality of learning material accessible online long-term.

Building learning into projects and their evaluation

The most important time to ensure learning is in the initial design of projects and programmes – especially in the writing of the Terms of Reference. Learning lessons from urban projects and actively making them accessible should be built into the DNA of urban projects. This is important while a project is being developed and implemented when there are opportunities for peer learning and training. It is especially important that well-developed materials are produced and validated by evaluation or research. These materials should be widely available after a project is finished and kept accessible to allow long-term learning.

Integrating learning into evaluation and research should also be part of project design from the start. This would ensure that there are outputs with a broader audience than management. We also need funding mechanisms for long term evaluation and research of selected projects to enhance lesson learning and dissemination. Linking this research to local universities can help get locally relevant lessons embedded in the education system.Footnote7 This is discussed further in the next recommendation.

Strengthen connection between projects and education training and research

In education and training it is important to have inputs from practitioners with direct field experience, as it provides an important perspective. Entry and advancement in academia is increasingly difficult for those with only a practice background. This makes it important to encourage course leaders to have inputs from practitioners and to be involved in projects themselves, though in my experience only short-term exposure also limits learning. See also (Stirrat, R.L. Citation2000). Where possible, linking teaching and research closely with the development and implementation of field projects can enhance both practice and teaching. Funding of local case study research and evaluation has proven a valuable approach to develop learning from local projects.Footnote8

Ensure quality learning materials and research is openly accessible online

Ultimately, we all Google for information and to find and read reportsFootnote9. Since the Covid-19 pandemic we also use apps, such as Zoom and Teams to attend lectures and conferences. The quantity of information is not a limitation, but the quality of well-developed material is. The short accessible pieces promoting new approaches are easy to find, but the soundly researched and deeply informative materials less so. To be a source for this requires urban projects to have specific outputs which facilitate learning. For evaluation, it means making evaluation reports publicly available or making a ‘learning version’ accessible. For academic research it means helping to ensure that project derived materials are as far as possible open access. Project reports and studies, which often contain valuable research, should also remain accessible and not disappear after a few years. Without them, long term studies are very difficult to implement and the potential lessons lost.

Conclusion

Urban projects have a valuable potential for learning and strengthening capacity. For this potential to be realised we need to integrate learning objectives into the design, review and evaluation of projects and programmes. We also need to strengthen the links between practice and education and ensure the long-term access to learning and other materials concerning projects and programmes.

Finally, though urban projects and programmes are a potentially valuable resource for learning, they are only a small part of practice. Learning from wider practice is equally important and also represents a valuable resource. Integrated approaches are becoming recognised as essential to tackle current and future urban issues including climate changeFootnote10. In the same way we need to integrate learning into project and programme practice to help achieve the urban development capacity we urgently need.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Forbes Davidson

Forbes Davidson works in the fields of urban planning and management, policy, and capacity development for sustainable cities. He is principal of his own consultancy and an associate of the Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies, Rotterdam, the Netherlands where he teaches in the areas of policy and planning. He has worked for extended periods in plan implementation, e.g., in Egypt in the Ismailia demonstration projects of upgrading and new development, Indonesia, India South Africa, Kosovo and Vietnam. Roles include expert inputs, leading teams, evaluation and the development of manuals and tools. Areas of focus include integrated strategic approaches, participation and capacity development related to issues including poverty reduction and resilience. Recent work includes Ghana (strategic and development planning), Egypt (decentralisation of integrated strategic planning), Palestine (institutionalisation of strategic planning process), Mongolia (consultant on management of district planning) and Vietnam working on the National Urban Development Strategy which seeks to integrated climate change adaptation and mitigation with urban planning, infrastructure investment and cross-sectoral coordination.

Notes

1. I use the term ‘urban projects’ to refer to planned interventions in urban development which try to achieve improved social, environmental, and economic outcomes. Much of what is written on projects also applies to urban programmes, which are wider both in geographical spread and in time and may include many individual projects.

2. The Asian Development Bank, for example, makes its project reports and evaluation reports available online (Asian Development Bank Citation2016). Lessons are included succinctly but are not designed for external learning.

3. The Ismailia Demonstration Projects were an UN-Habitat best practice, won the Habitat Award and received honourable mention in the Aga Khan awards for architecture. More information can be found at https://forbesdavidsonplanning.com/?page_id=1080 [accessed 17 January 2022].

4. For resources on the Ismailia projects see https://forbesdavidsonplanning.com/?page_id=1184

5. (Davidson and Payne Citation2000). The Urban Projects Manual is accessible online (see references for access). It was also translated into Spanish by Lund University in Sweden.

6. The Community Participation Training Programme was a DANIDA funded programme. Here communities monitored local performance and the results fed back directly into local activities. At the same time the reports fed into the larger system. In another project, also in Zambia, trainers visited the field where trainees were implementing projects and talked with the town clerk. This ensured that trainers and management were aware of the realities of the implementation situation and link practise closely with learning.

7. A recent example of this approach is found in the DEALS programme of VNG, The Netherlands Association of Municipalities in their project in Kumasi, Ghana.

8. This approach was implemented in institutional development projects of the Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS) over many years.

9. see also a wider discussion in (Tomlinson et al. Citation2010).

10. During COP26 in Glasgow 2021 the presentations I followed by local governments of their climate change mitigation and adaptation actions all focussed on integrated multi-stakeholder approaches.

References

- Asian Development Bank. 2016. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Public Sector Operations. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Madbouli M, Hassan GF 2011. Participatory Slum Upgrading, Documented Experience from Ismailia, Egypt. [accessed 2022 Jan 17]. https://forbesdavidsonplanning.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Ismalia-Documentation-Final-Report-03.08.2011-s.pdf

- Stirrat RL. 2000. Cultures of Consultancy. Crit Anthropol. 20(1):1. doi:10.1177/0308275X0002000103.

- Tomlinson R, Rizvi A, Salinas R, Garry S, Pehr J, Rodriguez F. 2010. The influence of google on urban policy in developing countries. Int J Urban Reg Res. 34(1):174–189. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00933.x.

- Davidson F, and Payne G , editors. 2000. Urban projects manual: a guide to the preparation of projects for new development and upgrading relevant to low-income groups, based on the approach used for the Ismailia Demonstration Projects, Egypt. 2nd. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press for Dept. for International Development. [Accessed 2022 Jan 17 2022]. https://forbesdavidsonplanning.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/urban-projects-manual.pdf.orHttp://gpa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2000/07/urban-projects-manual.pdf