ABSTRACT

Accessibility determines health care utilization among individuals with noncommunicable diseases as they need to visit health facilities frequently. Hence, we aimed to assess the road distance and travel time to the diabetes clinic of Persons with Diabetes (PWDs) seeking care at a public tertiary care facility in South India. PWDs house locations were geocoded using ArcGIS World Geocoding Services, and ArcGIS Pro Business Analyst Geoprocessing extension was used to conduct network analysis. A simple median regression analysis was done to compare the association of sociodemographic variables with distance and time. Of the total 2261 PWDs included, the mean (SD) age was 53.7 (11.5) years, and 49.4% were males and about 66.0% of the PWDs resided in rural areas. The median (IQR) travel distance of PWDs from their home to the diabetes clinic was 30.5 (7.6–78.5) km and the median (IQR) time spent in travelling was 77.9 (16.4–194.7) minutes. About 76% travelled more than 5 km to the diabetes clinic. About 85% of PWDs travelled farther than the nearest available public health facility to avail care from the diabetes clinic. Younger age group, male gender, PWDs from rural areas and the state of Tamil Nadu travelled significantly longer distance compared to their counterparts. To conclude, about three-fourth of the PWDs travelled more than 5 km for care at the diabetes clinic. Also, about 9 out of 10 travelled farther than the nearest available public health facility where diabetes care was available.

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the public health priorities in the world due to its chronicity and premature mortality associated with it. (World Health Organization, Citationn.d). Globally, 463 million people in the age group of 20–79 were living with diabetes in 2019, and one in five older adults (>65 years) has diabetes. (The International Diabetes Federation,Citationn.d). Diabetes was the reason for 1.2 million deaths in the South-East Asian region alone during 2019. (The International Diabetes Federation,Citationn.d). With 77 million Persons with Diabetes (PWDs), India is one of the diabetes capitals standing next to China in the absolute number of PWDs. Diabetes alone consumes 5–25% of an average Indian household income when a PWD is present, and the estimated country-level health care expenditure on Diabetes was US$ 31 billion in 2017. (Oberoi and Kansra Citation2020).

Easy access to a health care facility is essential in diabetes as diabetes requires the management process to be life-long and requires the patient’s continuous engagement with the health system. One of the unexplored aspects of diabetes care in India is the health care accessibility or distance travelled by PWDs to seek their care, which is a major concern for policy-makers globally. (Rekha et al. Citation2017). There are evidence that distance is a barrier to health care utilization and frequency of visits. (Bronstein and Morrisey Citation1990; Nemet and Bailey Citation2000). Also, there is a possibility of a rural–urban divide with persons from rural areas requiring to travel more distance than urban areas due to lack of services at rural health facilities. (Bliss et al. Citation2012). The travel distance directly impacts the cost of care as multiple studies have shown that the cost incurred due to travel and loss of wages contributes to health care expenditure among PWDs. (Fernandes and Fernandes Citation2017; Kamath, Rao, and Kamath A Citation2019; Teni et al. Citation2018). Chronic disease like diabetes needs continued expenditures on care, leading poor households into debt and illness complications. (Biswas and Kabir Citation2017). Therefore, proximity to medical care and availability of medications near PWDs home can reduce a significant expenditure on diabetes care. In order to improve the accessibility of care, in late 2018, the Indian government started Ayushman Bharat, a flagship programme aimed at providing comprehensive primary health care, bringing health care closer to people’s homes and ensuring free medicines for noncommunicable diseases. (Department of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, Citationn.d).

Data regarding PWD’s travel distance to diabetes care in India is limited. Spatial analyses can be used to estimate travel distance for diabetes care. (Billi, Pai, and Spahlinger Citation2007; Dubowitz et al. Citation2011; Higgs Citation2004; Kaukinen and Fulcher Citation2006; Miranda et al. Citation2005). Hence, in this study, we aimed to find the geographical locations and road distance to the diabetes clinic of PWDs seeking care from a public tertiary care facility in Puducherry, Southern India. We also aimed to determine the closest public health care facility and the shortest route to these health care facilities and compared the distance travelled based on sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted among PWDs attending a diabetes clinic in a tertiary care facility at Puducherry, Southern India, during October and November 2019. This facility is situated in the union territory of Puducherry and caters to patients from nearby districts of the state of Tamil Nadu. The Puducherry region encompasses 293 km2 and consists of a high concentration of large teaching hospitals, many private providers, and 27 geographically dispersed primary care centres that provide care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay. There are around 3000 public health facilities in Tamil Nadu state, providing diabetes care free of cost. The diabetes clinic in our hospital, run by the Department of Medicine, functions twice a week. Individuals with type 1 or type 2 diabetes sought care from this clinic, and all antidiabetic drugs, including insulin, were provided free of cost to all PWDs. Approximately 2500 PWDs visit the clinic every month, and health care providers advise them to visit the clinic every month for routine check-ups and medication refills.

Study population

A total of 2333 PWDs sought care from the diabetes clinic during the study period. We excluded the PWDs from the states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh (n = 72) due to a relatively long distance from the clinic and their irregularity to the clinic. PWD’s details, such as age, area of residence, gender, and residential address, were obtained from hospital management and information system (HMIS).

Study procedure

All eligible PWDs house locations (based on street name) were geocoded using ArcGIS World Geocoding Services, and 1789 (79.09%) locations got matched, and the rest were tied. Geo locations of public health facilities were obtained from the Directorate of Public health, Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry.

Distance calculation

ArcGIS Pro Business Analyst Geoprocessing extension was used to conduct network analysis to calculate the road/driving distance to the diabetes clinic/nearest public health facility. Euclidean distances and network distances (Manhattan distance) were calculated from coordinates of PWD’s current residential location and diabetes clinic location. The road-based network analysis covers all car travel simulated by travel along the roads, consisting of national highways, state highways, and roads in residential areas. From ArcGIS Online Routing services, driving distance/rural driving distance was selected as travel mode. Travel obeys one-way roads, avoids illegal turns, and follows other rules that are specific to cars. Elements that impact network distance, such as natural boundaries of rivers, street direction and accessibility, elements of the built environment and interstate highways, were also considered for distance calculation.

To calculate the travel time, ‘Car travel mode’ was used in the ArcGIS software. To perform the network analysis, the following attributes were considered in optimizing travel mode: cost, time cost and speed limit set to impedance, time cost and rural driving speed, respectively. Travel modes allow using network hierarchy for restricting attributes to optimize the time to reach the destination. Travel time to the nearest facility was estimated by optimizing the travel time in the model—the travel modes set to movements of small automobiles, such as cars or pickup trucks. Dynamic travel speeds based on traffic are used where available. Speed limit parameter value is set according to the rural driving speed. Statutory speed limits were fixed for different types of roads (i.e. 25 kilometres per hour (kmph) for roads in residential areas/rural roads, 55 kmph for state highways and 70 kmph for national highways) during free-flowing traffic, ideal weather conditions and the length of a speed zone of at least 1 km. All calculated distances were expressed in kilometres and time in minutes.

Ethics: The study protocol was reviewed by the Institute Ethics Committee of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, and the approval number JIP/IEC/2018/234 was assigned.

Statistical analysis

The ArcGIS Pro v2.5 software (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA) was used for spatial analysis, and the Stata version 14 was used for quantitative analysis. All patient data were anonymized before analyses. Continuous variable such as age was summarized as mean (SD). Categorical variables such as gender, area and the state of residence were summarized as proportions. The distance between the nearest public care site was dichotomized as either local (within 5 km) or non-local (>5 km). PWD’s travel distance and time were summarized as median (interquartile range). A simple median regression analysis was done to compare the mean values of different groups of patients. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 2261 PWDs, the mean (SD) age was 53.7 (11.5) years, and 49.4% were males. About 66.0% of the PWDs resided in rural areas, and 64.0% were from the state of Tamil Nadu. The sociodemographic characteristics of the PWDs are described in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of persons with diabetes attending a tertiary care centre, Puducherry, during 2018–2019 (N = 2261)

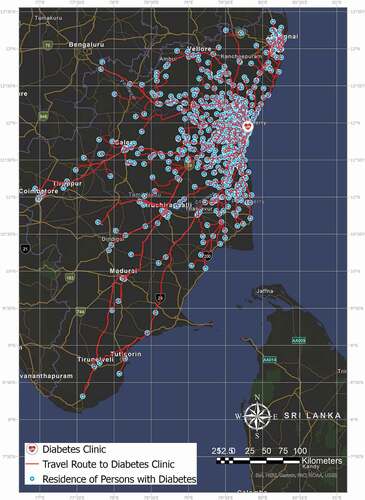

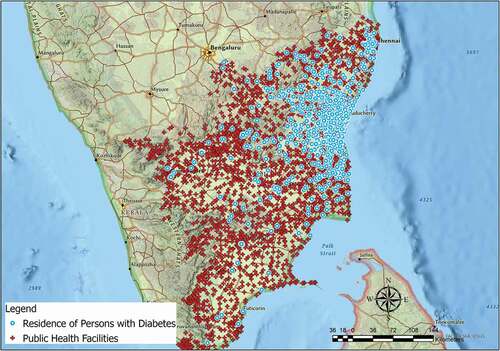

The spatial distribution (network diagram) of the study participants is depicted in . The median (IQR) travel distance (Manhattan distance) of PWDs from their home to the diabetes clinic was 30.5 (7.6–78.5) km and the median (IQR) time spent for travelling (driving) was 77.9 (16.4–194.7) minutes. About 76% travelled more than 5 km to the diabetes clinic. The spatial distribution of public health facilities and residence of PWDs are shown in , and the network analysis of travel distance between the residence of PWD’s home to their nearest public health facility is depicted in . The median (IQR) travel distance of PWDs from their home to the nearest public care site was 3.9 (1.4–8.0) km. About 85% of PWDs travelled farther than the nearest available public health facility to avail care from the diabetes clinic.

Figure 1. Locations and driving distance of persons with diabetes attending a diabetes clinic in a tertiary care facility, Puducherry, (N = 2261)

Figure 2. The spatial distribution of public health facilities and the residence of persons with diabetes (N = 2261)

Figure 3. Network analysis of driving distance of persons with diabetes to their closest public health facility where diabetes care is available (N = 2261)

shows the comparison of travel distance PWDs based on sociodemographic characteristics. PWDs aged less than 30 years travelled significantly more distances (43.8 km vs 22.1 km) compared to the older age group (P < 0.001). Men travelled significantly longer (33.4 km vs 21.1 km) than women (P < 0.001). PWDs from rural areas (35.7 km vs 3.5 km, P < 0.001) and the state of Tamil Nadu (49 km vs 2.3 km, P < 0.001) travelled a longer distance compared to their counterparts.

Table 2. Comparison of travel distance of persons with diabetes attending a diabetes clinic in a tertiary care facility, Puducherry, (N = 2261)

A comparison of time spent by PWDs to avail care at the diabetes clinic is depicted in . Younger age group, male gender, PWDs from rural areas and the state of Tamil Nadu travelled significantly longer to seek care from the clinic.

Table 3. Comparison of time spend by persons with diabetes availing care at a diabetes clinic in a tertiary care facility, Puducherry, (N = 2261)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to assess the distance travelled by PWDs using spatial analysis in India. Two-step Floating Catchment Method (2SFCA) to measure the spatial accessibility of health care facility is the most popular method in this kind of study. This method uses provider population ratio and catchment area within the drive time to measure the spatial accessibility index to identify the underserved locations in the community (Ikram, Hu, and Wang Citation2015; Luo and Wang Citation2003). The present study focused on finding the closest health facility from the residence of PWDs. We employed the ArcGIS Pro Network analyst tool ‘Closest Facility’ with road network hosted in ArcGIS online. The analysis is performed based on travel time with directions set to ‘towards facilities’ and travel mode is set to ‘cars and similar small automobiles’ with speed limits. Drive-time model output generated as driving directions/maps between the residence of PwDs to the closest facility with optimized travel time. A recently published study from the United States estimated a large drive time matrix between ZIP codes using algorithms of varying complexity and computational time to estimate drive times of different trip lengths to health care facilities (Hu et al. Citation2020). However, we did not consider this method due to the evidence for the ZIP code or PIN code area for the finest geographic scale at which health information is compiled and distributed in India is lacking.

This study found that the median distance travelled by PWDs to reach a diabetes clinic was 30.5 km and the median time spent in travelling (driving) was 77.9 minutes. Despite free diabetes care available in primary or secondary hospitals, these people are travelling to a tertiary facility. This finding indicates that proximity is not the driving factor in where people access diabetes care from a tertiary care centre. In contrast to our study findings, a study from the USA reported the average driving distance to HIV care was 7.08 km (Eberhart et al. Citation2014). Prior to implementing the ‘Ayushman Bharath’ programme in India, diabetes medications were not readily available at primary health care centres. This could be one of the reasons for the long travelling of our study population. However, currently, all PHCs are functioning on a 24 × 7 basis and provide free medications for diabetes and hypertension. Therefore, it is important to improve the patient’s awareness and a regular system to educate patients regarding the availability of medications at their nearby PHCs. It is also already known that the patients attending higher-level health care facilities like tertiary care hospitals were more satisfied with the care than those attending primary health centres. (Pankaj Bahuguna Citation2014). This also may influence the PWDs to travel more for diabetes care. Primary care services that include all necessary tests and treatments may entice more patients to their nearest PHCs (Olickal et al. Citation2021).

In the present study, PWDs aged less than 30 years travelled significantly more distances than the older age group. This is similar to a study from the USA. (Eberhart et al. Citation2014). Transportation is an important barrier to health care access, particularly for those with lower incomes or over-aged (Higgs Citation2004). However, comprehensive primary health care through ‘Ayushman Bharath’ programme in India ensures a seamless continuum of care at PHCs with equity, universality and no financial hardship. Lack of awareness about such services might be one of the reasons for long travel to tertiary care. Also, more educated young PWDs might prefer diabetes specialists for their care even though free diabetes care is available at their nearby PHCs. In the present study, men have travelled a greater distance than women, which is already reported by other studies (Eberhart et al. Citation2014; Syed, Gerber, and Sharp Citation2013). In the current study, PWDs from rural areas travelled more compared to their counterparts. This finding is similar to studies from western countries (Bliss et al. Citation2012; Eberhart et al. Citation2014; Huntington et al. Citation2010). PWDs from urban areas are more likely to reside close to health care facilities. A study from Tiruchirappalli district of Tamil Nadu, India, reported a spatial discrepancy in access to health care facilities in the rural population. (Rekha et al. Citation2017). Our study findings demand accessible quality of diabetes care at primary health care centres.

Strength and limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample used for this study is limited to PWDs regularly visiting the clinic and may not account for those who access care intermittently. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings is limited. We calculated network distance, assuming that the PWDs drove to the clinic; however, the actual mode of transportation is unknown. We do not take into account the factors associated with using public transportation. We used ArcGIS to identify the PWDs locations; the accuracy of ArcGIS is not validated in the Indian setting. Even though younger, male and high-income patients travelled longer than their comparison groups, the chances of unawareness, more faith in tertiary care and lack of an up-referral system for diabetes care might be contributing to the patient’s choices.

Conclusion

About three-fourth of the PWDs travelled more than 5 km for care at the diabetes clinic. Also, about 9 out of 10 travelled farther than the nearest available public health facility where diabetes care was available. Strengthening primary care facilities by an adequate supply of drugs and delivering regular training sessions for health care providers on diabetes care can attract more PWDs to their nearest public health facilities. Similarly, decentralizing diabetes care from the tertiary level by down referring eligible patients to their nearest primary or secondary facility centres for diabetes care needs to be considered to improve accessibility. Also, assessing the reasons for PWDs to choose care at tertiary care centres could have been useful for better health planning. Implementation of an up-referral system for diabetes care and restricting walk-in registrations at the tertiary level may reduce the long trips of PWDs. The current study findings are an eye-opener for a quality improvement project in the diabetes care hospitals to reduce long travel.

Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed by the Institute Ethics Committee of Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, and the approval number JIP/IEC/2018/234 was assigned.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Billi, J., C.-W. Pai, and D. Spahlinger. 2007. “The Effect of Distance to Primary Care Physician on Health Care Utilization and Disease Burden.” Health Care Management Review 32 (1): 22–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00004010-200701000-00004.

- Biswas, R. K., and E. Kabir. 2017. “Influence of Distance between Residence and Health Facilities on Non-communicable Diseases: An Assessment over Hypertension and Diabetes in Bangladesh.” PLoS One 12 (5): e0177027. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177027.

- Bliss, R. L., J. N. Katz, E. A. Wright, and E. Losina. 2012. “Estimating Proximity to Care: Are Straight Line and Zipcode Centroid Distances Acceptable Proxy Measures? Med.” Care 50 (1): 99–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822944d1.

- Bronstein, J. M., and M. A. Morrisey. 1990. “Determinants of Rural Travel Distance for Obstetrics Care.” Med. Care 28 (9): 853–865. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199009000-00013.

- Department of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, n d. National Health Mission – Tamil Nadu [WWW Document]. URL http://www.nrhmtn.gov.in/ (accessed 17 8 20).

- Dubowitz, T., M. Williams, E. D. Steiner, M. M. Weden, L. Miyashiro, D. Jacobson, and N. Lurie. 2011. “Using Geographic Information Systems to Match Local Health Needs with Public Health Services and Programs.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (9): 1664–1665. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300195.

- Eberhart, M. G., C. D. Voytek, A. Hillier, D. S. Metzger, M. B. Blank, and K. A. Brady. 2014. “Travel Distance to HIV Medical Care: A Geographic Analysis of Weighted Survey Data from the Medical Monitoring Project in Philadelphia, PA.” AIDS and Behavior 18 (4): 776–782. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0597-7.

- Fernandes, S. D., and S. D. A. Fernandes. 2017. “Economic Burden of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Socio-economic Impact on Household Expenditure in an Urban Slum Area.” Int. J. Res. Med. Sci 5 (5): 1808. doi:https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20171585.

- Higgs, G. 2004. “A Literature Review of the Use of GIS-Based Measures of Access to Health Care Services.” Heal. Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol 5 (2): 119–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-005-4304-7.

- Hu, Y., C. Wang, R. Li, and F. Wang. 2020. “Estimating a Large Drive Time Matrix between ZIP Codes in the United States: A Differential Sampling Approach.” J. Transp. Geogr 86: 102770. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102770.

- Huntington, S., T. Chadborn, B. Rice, A. Brown, and V. Delpech. 2010. “Travel for HIV Care in England: A Choice or a Necessity?” HIV Medicine 12 (6): 361–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00891.x.

- Ikram, S. Z., Y. Hu, and F. Wang. 2015. “Disparities in Spatial Accessibility of Pharmacies in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.” Geogr. Rev 105 (4): 492–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2015.12087.x.

- The International Diabetes Federation, n d. International Diabetes Federation - Diabetes in SEA [WWW Document]. URL https://idf.org/our-network/regions-members/south-east-asia/diabetes-in-sea.html (accessed 28 10 20b).

- Kamath, K. E., V. G. Rao, and C. R. Kamath A. 2019. “Annual Cost Incurred for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—A Community-based Study from Coastal Karnataka.” Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries 39 (3): 590–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-018-0691-5.

- Kaukinen, C., and C. Fulcher. 2006. “Mapping the Social Demography and Location of HIV Services across Toronto Neighbourhoods.” Health Soc. Care Community 14 (1): 37–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00595.x.

- Luo, W., and F. Wang. 2003. “Measures of Spatial Accessibility to Health Care in a GIS Environment: Synthesis and a Case Study in the Chicago Region.” Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des 30 (6): 865–884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b29120.

- Miranda, M. L., J. M. Silva, M. A. Overstreet Galeano, J. P. Brown, D. S. Campbell, E. Coley, C. S. Cowan, et al. 2005. “Building Geographic Information System Capacity in Local Health Departments: Lessons from a North Carolina Project.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (12): 2180–2185. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.048785.

- Nemet, G. F., and A. J. Bailey. 2000. “Distance and Health Care Utilization among the Rural Elderly.” Soc. Sci. Med 50 (9): 1197–1208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00365-2.

- Oberoi, S., and P. Kansra. 2020. “Economic Menace of Diabetes in India: A Systematic Review.” Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-020-00838-z.

- Olickal, J. J., B. S. Suryanarayana, P. Chinnakali, G. K. Saya, K. Ganapathy, T. Vivekanandhan, S. Subramanian, and D. K. S. Subrahmanyam. 2021. “Decentralizing Diabetes Care from Tertiary to Primary Care : How Many Persons with Diabetes Can Be Down-referred to Primary Care Settings?” J. Public Health (Bangkok) 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab156.

- Pankaj Bahuguna, D. S. 2014. “Predictors of Patient Satisfaction in Three Tiers of Health Care Facilities of North India.” J. Community Med. Health Educ s2. doi:https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.s2-002.

- Rekha, R. S., S. Wajid, N. Radhakrishnan, and S. Mathew. 2017. “Accessibility Analysis of Health Care Facility Using Geospatial Techniques.” Transp. Res. Procedia 27: 1163–1170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2017.12.078.

- Syed, S. T., B. S. Gerber, and L. K. Sharp. 2013. “Traveling Towards Disease: Transportation Barriers to Health Care Access.” Journal of Community Health 38 (5): 976–993. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1.

- Teni, F. S., B. M. Gebresillassie, E. M. Birru, S. A. Belachew, Y. G. Tefera, B. L. Wubishet, B. H. Tekleyes, and B. T. Yimer. 2018. “Costs Incurred by Outpatients at a University Hospital in Northwestern Ethiopia: A Cross-sectional Study.” BMC Health Serv. Res 18 (1): 842. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3628-2.

- World Health Organization, n d. Diabetes [WWW Document]. World Heal. Organ. URL https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed 28 10 20).