ABSTRACT

Many European countries are experiencing a recent (re)emergence of collaborative housing, such as co-housing, housing co-operatives and other forms of collective self-organised housing. One of the less studied aspects of these housing forms is the relationship between users (i.e. residents) and institutional actors and, in particular, established housing providers. This paper proposes a conceptual framework that helps expand the knowledge on the nature of these collaboration practices. To this end, different concepts and theories are reviewed, with a focus on collaboration and co-production as useful constructs to understand these phenomena. The proposed framework is applied to two examples of collaboration for housing co-production between residents’ groups and established housing providers in Vienna and Lyon, respectively. We found a high degree of user involvement throughout each project. In both cases, the group of residents that initiated the project partnered-up with established housing providers, who facilitated access to key resources and professional expertise. We hypothesise that housing providers with an ethos akin to initiators' values will more likely become (and stay) involved in collaborative housing, as compared to mainstream providers. We conclude with a reflection on possible improvements to our analytical framework and directions for further research.

Introduction

The global financial and economic crisis (GFEC) of 2008 resulted in the worsening of an already acute housing crisis in many parts of Europe, characterised by a chronic lack of supply, rising house prices and rents and growing homelessness. Austerity measures have driven further the steady reduction of public financial support to housing production and brought about restricted market finance opportunities for housing providers and households. As a result, not only vulnerable groups, but also increasingly middle classes have faced a sharp decline in their living standards (Parker, Citation2013) and are experiencing housing exclusion (CECODHAS, Citation2012).

Seeking to explain these developments and their impact in the housing field, some scholars have turned their attention to the reconfiguring role and identity of social housing providers across Europe (Czischke, Citation2014a; Houard, Citation2011; Scanlon, Whitehead & Fernández, Citation2014). Others contend that families are playing a pivotal role in negotiating their way through this home-ownership dominated policy landscape, and posit that market-dominated provision will be the predominant form of housing in the future (Ronald & Elsinga, Citation2012). More recently, there has been a growing interest on studying ‘alternative’ forms of housing provision, including the re-emergence of forms of collaborative housing (Fromm, Citation2012; Vestbro, Citation2010) in the post-crash context (Carriou, Citation2012; Minora, Mullins, & Jones, Citation2013; Moore & McKee, Citation2014; Moore & Mullins, Citation2013; Tummers, Citation2011, Citation2016). These comprise a wide array of initiatives,Footnote1 including co-housing, new types of residents’ co-operatives and other forms of collective self-organised housing. Overall, these types of housing are defined by high degrees of user participation, the establishment of reciprocal relationships, mutual help and solidarity, and different forms of crowd financing and management, amongst others. Sometimes these projects are targeted to specific socio-demographic groups, such as elderly people.

Amongst the less studied aspects of these forms of housing are the collaboration relationships between user groups (i.e. residents) and established housing providers, be they public, not-for-profit or co-operative. To realise their housing project, residents’ groups need to partner with a wide range of stakeholders, both individual and institutional, to access knowledge and resources. Evidence shows that established housing providers in different parts of Europe are beginning to engage with these initiatives for a variety of reasons, including the aim to empower residents and local communities where they operate, or their wish to ‘refresh’ their approaches through working with and learning from new grassroots actors (Czischke, Citation2014b; Devaux, Citation2011). However, there are a number of actual and latent tensions (for example, a history of mistrust) as well as untapped potential in these relationships.

To contribute to the knowledge on these collaboration practices and their effects, in this paper we review a series of concepts used to describe these practices. In particular, the paper focuses on the notion of ‘co-production’ to understand the relationship between ‘established’ housing providers (‘professionals’) and residents (‘users’) in collaborative housing projects. In order to understand collaboration and co-production, it is necessary to start by identifying the different types of stakeholders involved in these, as well as their respective roles, and the relationships with each other. To this end, the paper develops an analytical framework building on stakeholder analysis approaches (Alexander & Robertson, Citation2004; Sudiyono, Citation2013) and applies it to two concrete examples of collaborative housing.

Following this introduction, the section ‘The re-emergence of collaborative housing in Europe’ starts by defining our understanding of collaborative housing and provides the background within which this is currently developing across Europe. The section ‘Collaborative housing and co-production’ presents a review of concepts on collaboration and co-production and their linkages to collaborative housing. This section concludes with a proposal of an analytical framework building on stakeholder analysis approaches, distinguishing between ‘primary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘wider environment’ stakeholders. The section ‘Collaborative housing in Europe: an exploratory review of examples’ applies these concepts to two examples of such collaborations, one in Vienna (Austria) and the other in Lyon (France), drawing on findings from the author's case study research, including a short discussion. The section ‘Conclusions’ presents a set of reflections and questions for further research.

The re-emergence of collaborative housing in Europe

There are a variety of interrelated terms used both in practice and in the literature, often interchangeably, to refer to collective self-organised housing, such as ‘collaborative housing’, ‘community-led’, ‘resident-led’, ‘participative housing’ or ‘co-housing’. As Fromm (Citation2012, p. 364) explains ‘(…) in the classic co-housing developments originating in Denmark, the design encourages social contact, residents have a strong participatory role in the development process, complete management of their community, and typically share dining on a weekly basis, among other defining criteria’ (Fromm, Citation1991; McCamant & Durrett, Citation1988). We agree with Fromm in the relative restrictiveness of the definition of co-housing, as the degree of resident involvement and social contact implied in co-housing varies between different forms of self-organised housing. The same holds true for terms such as ‘resident-led’ or ‘participative’ housing, which imply high levels of resident leadership and/or involvement that differ significantly across different types of self-organised housing. The term ‘community-led housing’ is used widely in Anglophone contexts to refer to housing projects carried out by small groups of people living in the same locality and sharing a similar sense of identity (see for example Jarvis, Citation2015). However, the notion of ‘community’ does not bear the same significance in other contexts. Consequently, in this paper we have adopted the term ‘collaborative housing’ as an umbrella term for a variety of collective self-organised forms of housing, which is ‘wide enough to encompass all international variations’ (Fromm, Citation2012, p. 364). This definition also emphasises the collaborative nature of the relationships that residents have in this type of housing, both amongst each other and with a variety of external actors.

Overall, while in some European countries collaborative housing is part of broader long-standing traditions of cooperation and mutual help (e.g. Germany, Denmark), in others the latter were only marginal phenomena until recently (e.g. France, Belgium, etc.). In many cases their recent rise in numbers has been, at least partly, triggered by the GFEC and austerity measures mentioned earlier. In parallel to bottom-up movements, in many European countries there have been top-down attempts to stimulate inclusive societies and active citizenship. In the United Kingdom, for example, in recent years policy approaches such as the Big Society and Localism agendas seek to involve communities in the delivery of social services at local level as part of the trend towards State withdrawal from direct provision and/or funding. Similarly, in the Netherlands, the official discourse emphasises the need to move away from a welfare society towards a ‘participation society’ (participatiesamenleving). Furthermore, the new Housing Act (Nieuwe Woningwet) that came into effect in the Netherlands on 1 July 2015 introduces new opportunities for tenant organisations to be more involved in the general management of the housing associations as well as new legal opportunities to form residents’ housing co-operatives.Footnote2

In France, Biau and Bacqué (Citation2010) report an increasing number of small but innovative housing projects featuring residents’ participation in the design and management of their housing, alongside high environmental standards and the desire for neighbourly relations. This type of housing is called ‘habitat participatif’ in France (‘participatory housing’). These initiatives have partly been triggered by an increasingly unaffordable commercial housing offer. Following intense lobby by the citizens’ movement on ‘habitat participatif’, the law ALURFootnote3 came into effect in July 2015 providing statutory recognition to this type of housing. In Belgium, alongside an increasing number of co-housing projects (‘Habitat groupé’ or ‘woongemeenschappen’), recent years have seen the adaptation of the community land trust model to the context of the Brussels capital region as a new delivery mechanism for affordable housing provision, featuring a significant degree of user involvement.

The above examples point to a wide variety of drivers. Motivations such as quality of life aspects are common to previous waves of these projects (e.g. environmental sustainability, design aspects and social contact, amongst others). Nonetheless, in the current post-recession and austerity context in Europe, ‘affordability’ and ‘social inclusion’ feature as new driving forces in many cases (Bresson & Denèfle, Citation2015; Carriou, Citation2012; Chatterton, Citation2013). This marks a departure from the often ‘middle-class’ character attributed to these initiatives in the past, most notably co-housing projects. We posit that affordability as a driver can be seen as a response to the structural ‘crisis’ of social and affordable housing provision (even pre-dating the GFEC), as well as to a perceived failure by established housing providers (be they commercial, state-owned or third sector) to deliver housing for wider sections of the population (Czischke, Citation2014a). Hence, in this paper, our focus will be on collaborative housing initiatives in Europe that place themselves within this quest for affordable and socially inclusive housing.

A paradigm shift in public participation

Collaborative housing falls within a wider paradigm shift in public participation, underpinned by the recent (re)emergence of concepts such as ‘social innovation’, ‘community-led development’ and ‘co-production’, amongst others. Most of these ideas are not new, but have been revisited by scholars and policy-makers over the last couple of decades to shed light on the structural and symbolic aspects of the changing nature of public service provision in advanced capitalist societies.

This new paradigm can also be related to recent changes in the respective roles of the state and the individual citizen in the provision of public services as well as in their relationship. As observed by scholars like Gofen (Citation2015) and Needham (Citation2008), a series of successive shifts in these roles and relationships have occurred since the days of the post-war welfare state in Western European societies, when citizens where viewed as ‘recipients’, ‘subjects’ or ‘users’ of public services. From the mid-1980s onwards, a ‘customer’ orientation to citizens has become the norm, viewing them as ‘consumers’ (Clarke, Citation2007) or as ‘customers’ (Mathiasen, Citation1999) who should be ‘served, satisfied, and provided with a choice between alternative service providers’ (Gofen, Citation2015, p. 405). In the field of housing, these shifts can be related to different ‘stages’ in the provision of social or public housing in Western Europe since 1945.

Building on Whitehead (Citation2015), a first stage corresponds to the post-war large-scale production of social housing by the State, where the role of third sector organisations became marginal – in contrast to their leading role in the provision of social housing at the turn of the twentieth century. At this time, citizens were ‘beneficiaries’ of this type of housing. Stage two shows the period beginning in the 1980s, where the State began to withdraw from direct provision and took the role of commissioner and regulator of social housing provided by – to different extents and in different combinations across countries – both local authorities and third sector organisations (e.g. housing associations and other not-for-profit professional housing providers). Third sector provision grew in some countries due to the privatisation of formerly public housing stock (e.g. England, the Netherlands) and its practice became influenced by ‘New Public Management’ approaches (Walker, Citation1998), which aim to transpose private sector management practices to public service delivery, and regards users as ‘customers’. Since the late 1990s and up until today, State withdrawal has deepened across most member states of the now enlarged European Union, accentuated by the effects of the GFEC and austerity policies. The latter is linked to the increasing influence of discourses of responsibilisation (Dean, Citation2010; Lemke, Citation2001; Rose, Citation1999), including the housing field (Flint, Citation2004; Heeg, Citation2013; McIntyre & McKee, Citation2012), which reconceptualises social problems and risks as individual problems that individuals are primarily responsible for managing. Within this context, ‘co-production’ emphasises the transformative aspect of service delivery for citizens (Alford, Citation1998; Boyle & Harris, Citation2009; Cahn, Citation2004) as well as the unique characteristic of service as a simultaneous process of production and consumption.

Collaborative housing and co-production

In this section, we review some theoretical developments underpinning the concepts of co-production and collaboration in order to establish their links to collaborative housing.

Linking co-production to collaborative housing

The concept of ‘co-production’ was first coined by Elinor Ostrom (e.g. Ostrom, Citation1996; Ostrom & Baugh, Citation1973) and has been recently re-examined by scholars seeking to interpret new developments in public service provision involving

(…) the mix of activities that both public service agents and citizens contribute to the provision of public services. The former are involved as professionals, or ‘regular producers’, while ‘citizen production’ is based on voluntary efforts by individuals and groups to enhance the quality and/or quantity of the services they use. (Parks, Citation1981)

Following a public management perspective, Pestoff and Brandsen (Citation2013, p. 5) define coproduction as ‘the arrangement where individual citizens produce their own services in full or part with public service professionals’. In this paper, we take this definition as a starting point to refer to co-production in housing, albeit with three remarks.

First, as described above, the concept of co-production was coined to refer to ‘public’ services, i.e. services provided either entirely or partially by government, or funded (subsidised) by it. However, collaborative housing initiatives include a wide range of housing tenures and funding sources, often but not always involving subsidised housing. This varies not only on a project-by-project basis, but also according to the different types of legal and financial frameworks to provide affordable and social housing in each country. Hence, in this paper, we adopt a broader definition of co-production in collaborative housing, which includes some form of subsidised housing as part of a variety of tenures and funding sources.

Second, Pestoff and Brandsen's definition (Citation2013) refers to established providers in terms of ‘public service’ professionals. This overlooks the fact that in many European countries social housing is provided by a range of third sector organisations entrusted by law with a public service obligation to deliver such service (Bauer, Czischke, Hegedüs, Pittini, & Teller, Citation2011). Furthermore, the profile of established providers differs not only across specific projects, but also across countries, and thus does not always correspond to a public service professional. Again, in this paper, we adopt a broader definition of established provider, encompassing organisations and individuals who act in a professional capacity as housing providers (e.g. housing associations, private architecture firms, etc.).

Third, in collaborative housing, the user is not an individual, but rather a group of people who share a set of basic values that define the housing project where they want to live.

These new partnerships open up new collaboration processes that lead every actor to reposition him or herself (Alford, Citation1998). Leadbeater (Citation2004) argues that in some cases service providers can transform their role to that of a facilitator of platforms and networks, thereby freeing up manpower and workload. Over the course of co-production processes, boundaries between what is specific to the ‘professional’ or to the ‘user’ become fuzzy, creating space for cross-fertilisation of technical and practical knowledge. At an organisational level, this could result in higher levels of hybridisation (Czischke, Citation2014a; Mullins, Czischke, & Van Bortel, Citation2014).

In line with the above, we define collaborative housing as the arrangement where a group of people co-produce their own housing in full or part in collaboration with established providers. The degree of user involvement in this process may vary from high level of participation in delivery and design within the context of a provider-led housing project, to a leading role of the user group in the different stages of the housing production process.

A continuum of user involvement in collaborative housing

Some advocates of co-production frame it within a radical critique of public services. In the UK context, for example, Boyle and Harris (Citation2009) state that ‘[c]o-production means delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their family and their neighbours’ (2009, p. 14). They emphasise that co-production should not be confused with consultation, as it ‘depends on a fundamental shift in the balance of power between public service professionals and users’ (Boyle & Harris, Citation2009, p. 17). This ‘equal partnership’ between professionals and users is deemed to afford equal value to different kinds of knowledge and skills, which is expected to change the perceptions and the approach of many public service professionals.

However, others express less enthusiasm for the alleged benefits of co-production for public services. While agreeing that the co-production discourse poses ‘relevant questions about the changing nature and value of professional work, expertise and knowledge’, Fenwick (Citation2012) cautions that much of the existing debate and research about co-production is concentrated at the level of policy and prescription, tending to neglect what actually happens in the concrete practices of these arrangements. This view echoes the Dunston, Lee, Boud, Brodie, and Chiarella (Citation2008) call for evidence that demonstrates the effectiveness, feasibility and undesirable consequences of co-production approaches prior to its prescription for policy reform. Accounts of these practices, Fenwick claims, can ‘(…) help contribute to more multi-layered models of co-production’ (2012, p. 2). In contrast to views of a single ideal of co-production where users are simultaneously co-deliverers and co-designers (Bovaird, Citation2007; Boyle & Harris, Citation2009), Fenwick believes that users may be one and/or the other to different extents. This implies a more pluralistic model based on the notion of a continuum of co-production (Fenwick, Citation2012, p. 13).

Understanding the changes that co-production can bring about in professionals also requires an investigation into individual values, on one hand, and organisational culture, on the other. Biau and Bacque (Citation2010) found that those who commit to working with residents in these projects have a specific profile, which they describe as ‘militant’, as their involvement in these operations requires a significant investment in terms of time and personal commitment. At an organisational level, this investment is often seen by executives as part of a longer term strategy to develop new practices and even the potential development of a new market niche. This requires a specific set of values both from the individual and the organisation. We could hypothesise that organisations where higher levels of leadership are committed to this agenda will tend to engage more consistently and over the longer term with these initiatives, thereby setting the basis for more structured ways of co-production. Furthermore, their organisations would see wide-ranging transformations covering their structures, processes, asset management strategies and notably their front line operations, requiring new competences from their staff.

At the other extreme is a situation where citizens are dissatisfied with a public service to the point when they decide to provide it by themselves. This can be described using Gofen's (Citation2012, Citation2015) concept of ‘entrepreneurial exit’, which denotes ‘the proactive initiation, production, and delivery of alternative service by citizens, mainly for their own use’ (Gofen, Citation2015, p. 405).

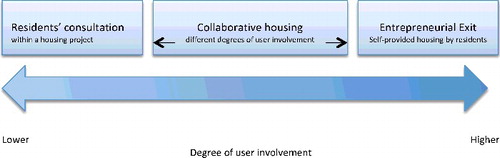

We can conclude that collaborative housing takes place alongside a continuum of user involvement in the provision of residents’ own housing, along the lines of Fenwick's idea of co-production (Citation2012). As illustrated in , at the lowest end of user involvement is ‘consultation’ to different degrees of involvement in co-production processes. This would happen, for example, when tenants of housing associations or future residents in a housing development are asked about their preferences with regards to a specific action by the provider, following Arnstein's notion of consultation in her ‘ladder of participation’ (1969). The highest end of this continuum is represented by Gofen's (Citation2012) ‘entrepreneurial exit (EE)’, which in housing could take the form of (almost) entirely self-organised and self-managed housing projects by residents.

Analysing stakeholders in collaborative housing

Collaboration enables individuals to work together to achieve a defined common purpose. This often involves working across boundaries and in multi-sector and multi-actor relationships. Poocharoen and Ting (Citation2015) compare the concepts of collaboration and co-production. While the former focuses on the organisational level, the latter focuses on the individual level, i.e. citizens and professionals. Crucially, in co-production one person or organisation can simultaneously be both the producer and the consumer of the service. In this view, collaboration is a broader concept than co-production, covering ‘all types of relationships between entities to get things done (…). These entities are from public, private and non-profit sectors combined’ (Poocharoen & Ting, Citation2015, p. 589). This diversity often entails a high degree of complexity, encompassing different motives, institutional logics and behaviour (Czischke, Citation2014a; Mullins, Citation2006; Sacranie, Citation2011). The concept of ‘collaborative management’ describes ‘the process of facilitating and operating in multi-organisational arrangements to solve problems that cannot be solved or solved easily by single organisations’ (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2004, p. 4).

This broad conception of collaboration has clear links with the notion of networks. Extensively researched and theorised over the last few decades, networks can be broadly defined as ‘structures involving multiple nodes - individuals, agencies, or organisations - with multiple linkages’ (McGuire, Citation2006). Network structures are typically intersectional, intergovernmental, and based functionally in a specific policy or policy area. Recognising the many linkages between these different concepts, Poocharoen and Ting (Citation2015) posit that ‘most co-production processes are usually part of a larger set of relations within a public service delivery network. [Thus] in order to be able to see and study these relationships clearly, the researcher must either ‘zoom in or zoom out’ when necessary’ (2015, p. 595). As part of wider collaboration and network settings, co-production involves a variety of individual and institutional actors or stakeholders with different motives and institutional logics. A ‘project stakeholder’ can be defined as

(…) someone who gains or loses something (could be functionality, revenue, status, compliance with rules, and so on) as a result of that project. (…) A stakeholder can be someone who finances the project; someone whose skill is needed to build a product (…); an organisation whose rules developers must obey, (…); or an external organisation that can influence project success. (Alexander & Robertson, Citation2004, pp. 23–24)

The stakeholder onion diagram (Alexander & Robertson, Citation2004) is a way of visualising the relationship of stakeholders to a project goal. The diagram allows the identification and characterisation of each stakeholder's role in the process. A stakeholder who is involved only indirectly – the regulator, for example – is distant from the centre. Conversely, closeness to the centre indicates direct operational involvement. Sudiyono (Citation2013) applied the stakeholder onion model in his study of co-housing projects in Berlin. Starting from ‘the co-housing project’ at the centre, he categorised stakeholders into three different roles, each of them assigned to one of the layers according to factors such as their relative legitimacy, control over essential resources and whether they had a veto or not. In addition, Sudiyono's diagram distinguishes three different domains to which stakeholders belong: market, state and civil society. To depict this, he drew three dashed lines from the centre towards the outer layers of the diagram, dividing the onion in three pie slices.

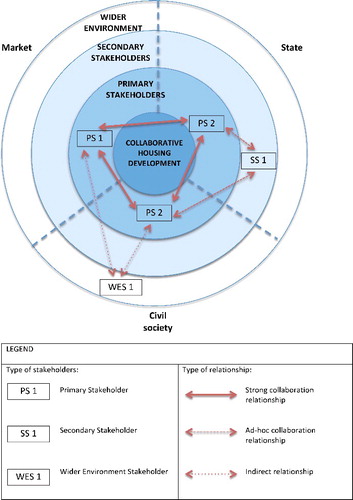

Combining elements from Alexander and Robertson's original model with Sudiyono's applied version of the former we propose a diagram that illustrates co-production in collaborative housing. In our diagram, the collaborative housing development (CHD) involves the design, planning, construction, refurbishment or renovation, and management of housing for the main residential use of the participating households. We propose three levels of analysis, from centre to the outer circle (see ). In line with Sudiyono's classification, we focus on three key elements that define the relative position of stakeholders and their relationships, and define them as follows:

Legitimacy: following Suchman (Citation1995, p. 574), we understand legitimacy in these collaborations as a ‘(…) generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’.

Control over essential resources: this relates a stakeholder having exclusive power over any type of resource that is crucial to achieve the realisation of the CHD, for example, money (e.g. lending institutions), land (e.g. local governments), access to public subsidies (e.g. institutional housing providers), etc.

Veto: refers to the power to unilaterally stop an action within the framework of the CHD.

Level I: Primary stakeholders: those who have significant influence in the CHD or stakeholders with strong legitimacy and /or strong control over essential resources. Primary stakeholders have a veto. Typically this level will include the residents’ group as users and producers of their housing as well as professional ‘established’ housing providers (i.e. housing organisations and/or architecture firms) who are involved in the day-to-day operations of the housing development. Hence, co-production takes place between actors located in this layer albeit as part of a series of collaboration relationships with other stakeholders located in the additional outer layers/levels of analysis (see below).

Level II: Secondary stakeholders: they play an important role in the project but, unlike primary stakeholders, they are not involved in its day-to-day operations. Their respective legitimacy and control over essential resources may vary from medium to high (e.g. a bank, a local authority facilitating land, etc.). Usually this level will include those stakeholders that provide an important resource to the project but are only involved in an ad-hoc or episodic manner with it, e.g. a bank or lending agency, a public authority body, etc.

Level III: The wider environment in which the CHD takes place: it contains individuals or organisations that are indirectly affected by the CHD. Compared to stakeholders in the inner layers, most of these have relatively weak legitimacy and weak control over essential resources. However, their actions and competences provide a framework for the development of the project. These may include, for example, clients, suppliers, financial beneficiaries, the public, the media, and other similar entities. Regulatory institutions are included in this sphere due to their indirect involvement with the project, despite their usually strong legitimacy.

Figure 2. Illustrative diagram of multi-stakeholder relationships in collaborative housing developments.

Relationships between the different stakeholders are depicted in the diagram through dashed arrows. As shown in , we have classified these relationships in to three types, taking into account aspects mentioned above:

‘Strong’ collaboration relationship: related to day-to-day operational aspects of the project, of high frequency and mutually interdependent.

‘Ad-hoc’ collaboration relationship: limited to specific exchanges on usually technical matters, e.g. financing, service provision (e.g. special care needs, etc.).

‘Indirect’ relationship: latent or implicit, e.g. of legal or regulatory nature.

Figure 3. Collaboration and co-production relationships in the women's housing project [ro*sa]²² – Vienna, Austria.

![Figure 3. Collaboration and co-production relationships in the women's housing project [ro*sa]²² – Vienna, Austria.](/cms/asset/18b2623d-988b-412d-8e2a-709017a5ee46/reuj_a_1331593_f0003_oc.jpg)

In addition to the different levels of stakeholder involvement in our diagram we apply Sudiyono's (Citation2013) distinction between market, state and civil society actors. This distinction can shed light into the motives, agendas and institutional logics (Mullins, Citation2006; Pache & Santos, Citation2013; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008) of the different types of stakeholders.

Collaborative housing in Europe: an exploratory review of examples

In this section, we illustrate how our analytical framework can help to understand collaboration and co-production in housing through identifying different types of stakeholders, their roles and relationships. To do so, we briefly present two cases researched by the author, one in Vienna (Austria) and the other in Grand Lyon (France), where the initiators (residents’ groups) partnered with established providers. In both countries, there is a well-established sector of ‘institutional’ social housing providers. In each country, examples of co-production in housing differ in their origin and evolution; while in Austria collaborative housing projects have been part of the housing system for a long time, in France this is a relatively new phenomenon.

Data for both case studies were gathered in three rounds: first, desk-research (March–October 2014). Second, in-depth interviews on the French case study (July–September 2015) comprising one resident and initiator of the project and a representative of Habicoop, the NGO facilitating the project. In addition, interviews with two key informants provided critical insights on the case as well as on the wider context of ‘habitat participatif’ (collaborative housing) in France, namely: the co-ordinator of the network of French housing providers working with residents in ‘habitat participatif’, within the French federation of social housing providers (Union Sociale pour l'Habitat) and an architect working with this type of projects. A third round took place in Vienna (March 2016), including project visits and face-to-face interviews with two residents and initiators of [ro*sa]²²; the CEO of housing association WBW-GPA and other stakeholders; and two representatives of the umbrella body for collaborative housing ‘Initiative für Gemeinschaftliches Bauen und Wohnen’, who provided critical insights into the project as well as on the wider context of collaborative housing in the Viennese context.

Case 1: the women‘s housing project [ro*sa]²², Vienna (Austria)

This housing development is located in Vienna's 22nd district. The initiator was the architect Sabine Pollak from the Köb & Pollak Architecture office, who had been involved with gender and housing issues and had the idea of a collaborative housing project developed specifically to address women's needs. Pollak believed that not only the wishes but also the knowledge of the future residents should be incorporated into the project planning. In 2002, she organised discussions about her project idea through various feminist groups. Many women living alone attended these early meetings and expressed their housing preferences. Design elements that featured widely amongst their aspirations were small apartments, accessibility, many common areas and large transition zones between common and private spaces. Out of these discussions, the [ro*sa] organisation was formed, which then developed the project's idea further.

Pollak's project came second in a competition organised by the Wohnfonds Wien.Footnote4 However, the Jury liked the concept and recommended that Wohnfonds facilitate land to build the project. The involvement of a housing company was then required to buy the allocated land. To this end, Pollak approached the Wohnvereinigung für Privatangestellte (Housing association for private employees – WBV-GPA), which had a track record as socially engaged and progressive housing company, having developed similar gender-oriented projects in the past. The housing association acted as developer of the project and channelled funding to it (municipal subsidised loan and bank loans). Currently, WBV-GPA manages the allocation of dwellings under local authority conditions.

Affordable rents were a key challenge for the project, notably because many of the single mothers and older women had limited financial means. The Viennese system of municipal (subsidised) loans for construction, as well as individual housing allowances contribute to this goal. After ten years, tenants have the option to buy their flat. To this end, an agreement needs to be reached with WBW-GPA, stating that the resale of the flat would only be possible to people meeting the main criteria, namely women interested in the philosophy of the housing project. This also holds for the case of re-lets. The Wohnservice Wien is the municipal body responsible for the allocation of a third of the flats to people who are eligible for social housing. This ensures the inclusion of households with different incomes in the project.

Collaboration in the women's housing project [ro*sa]²²

depicts the main stakeholders in this development and their relationships. Primary stakeholders – located in the first layer from centre out – were the architecture firm, the initial group of residents (in the shape of the [ro*sa]²² organisation) and WBV-GPA. The initiator was the architect, who had a vision of the project and called on a wider group of interested individuals (women) to shape the concept together. We have located this actor on the boundary between the market and civil society; on the one hand, as they operate in a commercial environment. On the other hand, in this case her motives included a wider social purpose linked to civil society values (gender and social inclusion). The residents’ group belongs to the civil society sphere. As a market operator with a social purpose, we have placed the housing association WBV-GPA on the boundary between the market and civil society spheres.

As explained in our analytical diagram, co-production relationships are those amongst primary stakeholders (established providers and user/residents). In this case, roles traditionally performed by established housing providers are shared between all three primary actors, although to different extents and at different stages: the architect and the initial group of residents carried out the general conceptualisation and planning of the project together. They also recruited the wider group of residents. Residents take care of daily management activities in their building and communal life following completion of the building and its initial occupation. The housing association joined the project shortly after the initial conceptualisation and planning stage, and took the lead on the construction and management of the project. It also acted as intermediary lender, channelling funding from banks. Since completion of the building and the initial allocation of dwellings to the first group of residents, the housing association continues to act as allocation manager for two thirds of the dwellings and owns the building and the land. The [ro*sa]22 organisation has a period of two months to propose tenants, who then finalise their leases with WBV-GPA. When selecting new tenants, WBV-GPA is required to inform applicants early on about the concept and expectations of [ro*sa]22 (Lafond, Citation2012, p. 137). Hence, each of these actors control essential resources and has strong legitimacy vis-à-vis the project.

Secondary stakeholders, depicted on the second layer from centre out, include the different agencies of the City of Vienna, notably the Wohnservice (provides subsidised loans for social housing construction, housing allowances and handles allocations) and the Wohnfonds (oversees subsidised housing construction and facilitates land through competitions) and the bank that financed the project (market actor). The feminist groups were the only civil society stakeholders identified as relevant for this project in our exploratory research. This does not mean, however, that in practice there are no other relevant stakeholders to include in this layer: the regulator, NGO's, the media, etc., could also be considered in this layer albeit implicitly at this level of analysis.

Case 2: residents’ housing co-operative ‘Le Village Vertical’, Villeurbanne (Grand Lyon), France

The initiators were a group of people eligible for social housing who wished to live in a housing project that met their ecological and social values. They also wanted to open the project to very low-income households, e.g. the unemployed and people facing other types of social disadvantage. The group believed that low-income households could greatly benefit from a reduction of energy bills that an energy-efficient building can provide, as well as from the solidarity of the wider group.

In 2006, the residents’ group partnered with the Habicoop association, a not-for-profit organisation founded in 2005 whose mission is to help the development of resident-led housing projects in France. Habicoop was looking for a pilot group in its quest to achieve recognition of the legal form ‘residents’ co-operative’ (RC) for this type of housing. Habicoop acted as facilitator of the process by bringing partners together and advising the residents’ group, especially on the planning, financial and legal structure of the project. Interested to support this type of initiatives, the Mayor of Grand Lyon agreed to sell land from a pool of public land available to projects in qualifying areas (ZACFootnote5 des Maisons - Neuves, Villeurbanne) to the RC.

In 2007, the RC partnered with a HLM social housing organisation born out of an earlier housing co-operative, Rhône-Saône-Habitat (RSH). The RC chose this housing provider as it was well known to them, having acted as ‘syndic’Footnote6 in other housing projects. RSH built 24 dwellings for social ownership as part of the housing project. In the same building, the RC built 14 flats, out of which nine are social housing (PLS),Footnote7 and four ‘very’ social housing (PLAI).Footnote8 RSH took charge of the development of the building. According to A. Limouzin, one of the residents who initiated the project (personal communication, 10 July 2015) the CEO of RSH had a personal commitment to this type of project. The CEO has declared that participating in it ‘revived a dimension that had been somewhat forgotten in our social co-operative work: co-operation, “working with”’ (Leclerc, Citation2013).

The group chose an architecture firm with expertise in ecological construction, which suited their aspirations in this domain. It was the first time that this architecture firm worked in a resident-led housing project. According to A. Limouzin (personal communication, 10 July 2015), the architects invested significant time and effort in this process and although it was commercially not very successful they valued having acquired experience in resident-led housing.

The social housing organisation financed the construction, acting as a de facto intermediary between the banks and the residents’ group. Upon settling into their new homes, the residents started to pay back the loan to RSH at an agreed below-market rate. RSH also acts as security for the bank by providing a safety net if any of the RC tenants has to move into social rental housing. RSH will continue to own and manage the four very social housing flats (PLAI) for 30 years. After that period, the RC will become the owner of these flats. An association called AILOJ helps recruit tenants for the PLAI flats and also takes care of special needs they may have (e.g. the young unemployed, disabled, etc.). Residents support AILOJ with these tasks on a voluntary basis.

The whole building is co-owned by the RC and RSH. By buying shares of the RC, residents have a right to vote on important decisions according to the principle ‘one person, one vote’. They are collective owners of the building where they will live. Each pays rent to the co-operative society based on the size of their home: individually, they are tenants of their flat. This is a way to fight against speculation. All residents may use common spaces such as terraces, laundry room, a common room with a kitchen, a vegetable garden, etc.

Collaboration in the residents’ co-operative ‘Le Village Vertical’

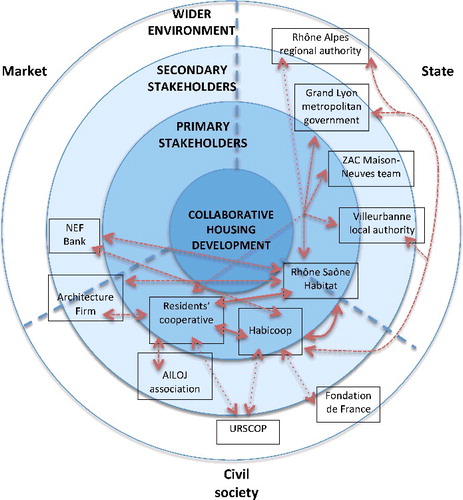

As depicted in , primary stakeholders in this project are the residents’ group (in the shape of a residents’ co-operative since 2010), the social housing organisation Rhône-Saône-Habitat and the Habicoop association. Both the residents’ co-operative and Habicoop belong to the civil society sphere, while the housing association sits on the border of the civil society domain (due to its co-operative ethos) and the public sector sphere (due to its legal status as HLM organisation). As seen earlier, RSH performed roles typically associated with those of an established housing provider, including developing and managing the housing project and implementing social housing allocation policy. In addition, it acted as intermediate lender with no or limited profit, which is in line with its declared social and co-operative mission.

Figure 4. Collaboration and co-production in the residents’ co-operative ‘Le Village Vertical’ – Villeurbanne (Lyon), France.

The Habicoop association played a variety of roles, including intermediary and facilitator (by helping to bring stakeholders together) and advisor on technical matters (e.g. legal and financial). In this sense, it can be regarded as a hybrid type of actor, transferring technical knowledge to users and interpreting their needs so as to connect them with the appropriate stakeholder. In addition, Habicoop reaches out to the wider environment through its networking and advocacy roles.

Secondary stakeholders include the architecture firm, the AILOJ association and public sector actors such as the Grand Lyon metropolitan government, the municipality of Villeurbanne, and the regional government of Rhône Alpes. We have placed the architects in this case in a secondary role, as their input was limited to providing expertise and technical knowledge that supported and enabled the original social, ecological and architectural ideas of the group of residents. The latter played a central role by co-designing the building; for example, they made choices regarding the architecture and building material.

Stakeholders in the wider environment are the Rhône Alpes regional government, Fondation de France and the URSCOP (Union Régionale des sociétés coopératives). As with the Viennese case, these actors featured in this exploratory study and therefore do not necessarily exhaust the list of actual wider environment stakeholders.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss the above findings under three sub-headings: first, the type and core values of each project; second, the shapes that collaboration takes between stakeholders in each case; and third, an emerging hypothesis and a reflection on how to improve our analytical model as a result of this exercise.

The projects and their core values

Both projects were strongly user-led, carrying a vision and a set of values from the beginning and throughout their development. Residents had a veto on aspects affecting core values driving their projects. Both sought social inclusion and affordability through mechanisms of tenure and income mix, linking with local social housing allocation systems. In Village Vertical, affordability features at the core of the residents’ co-operative legal form, which prevents any individual value capture through combining collective ownership of the building and individual tenancy. In Vienna, the project made use of existing municipal housing financial support mechanisms, both to individuals (allowances) and to providers (loans). Each project had a specific thematic focus: gender in Vienna and environmental sustainability in Lyon. However, in each case the above visions and values had a different origin. In Vienna, the initial concept was proposed by an individual (the architect), who tapped into a latent demand and target group; in Lyon it was the residents’ group that developed the vision for their housing project from the onset.

Collaboration with stakeholders

As shown in in both cases established housing providers were primary stakeholders, taking on the role of developers and property managers. Both also retained ownership of the land and buildings, acted as intermediary lenders and implemented local authority policies for the allocation of social housing. In both examples, the relationships between the residents’ group and housing providers were established from the early stages of the project and were initiated by the residents’ groups. This matches the high degree of user involvement that each of these groups took over the course of their project, notably on the overall guiding values and on architectural design aspects. In Village Vertical, a third type of primary actor, Habicoop, played a facilitating role, mediating the access to key resources (i.e. land, money, planning permission, etc.) and to other relevant stakeholders in the wider environment. The role of the architect (or architecture firm) in each case varied significantly. While in the women's project the architect was at its very origin, in Village Vertical this actor took a less central role, focusing on providing technical expertise. The former example is in line with the usual modus operandi of resident-led housing in German speaking countries (‘Baugruppen’), where architects tend to take the lead and perform a variety of additional roles, such as facilitators of the whole project. In both cases, however, co-production took the shape of co-design of architectural features and co-decision about materials and construction processes. In Village Vertical, the links to the wider co-operative movement in France stand out. These stretched from the local level (RSH) to the regional (URSCOP) and even national level (through Habicoop).

Table 1. Comparative overview: stakeholders and their roles in each project.

Emerging hypothesis and improvements to the analytical model

From the above comparison, we can hypothesise that established housing providers with a particular ethos, akin to the values of the initiators, are more likely to become involved in collaborative housing than those without this orientation. In both examples an established housing provider was approached by the initiators in view of their respective track record of involvement in similar projects. Furthermore, both providers consider this type of project in line with their core values, be it an ‘original militant, co-operative ethos’ (RSH) or a socially progressive, gender-mainstreaming orientation (WBV-GPA). This is in line with findings by Biau and Bacque (Citation2010) regarding a specific type of organisational culture as well as of individual values held by staff (and notably by the organisation's leaders) required to support and sustain the commitment to this type of projects.

The analytical diagrams illustrate the number and variety of stakeholders also according to their sphere of action, i.e. market, state or civil society. In Village Vertical, for example, looking at the diagram a high density of public and civil society actors becomes evident. Depending on the project, some of these actors will acquire more prominence than others. For instance, in housing projects with a strong emphasis on ‘special needs’, actors such as social care agencies or providers will be likely to play a much more central role than in other projects. In Village Vertical, the strong social inclusion and solidarity values held by the initial group of residents resulted in a partnership with the social care association AILOJ. In Vienna's women's project, the centrality of the gender dimension resonated with local feminist groups within the wider environment. Not only were they a source of possible tenants, but also a wider basis of social, cultural and political support.

Our analytical diagram could be developed further. For instance, at the level of the ‘wider environment’, it could consider the links between specific projects and their embeddedness within local, regional and national policy and legal frameworks. This would allow testing the relative influence of different government levels on the realisation of the collaborative housing project. In our examples, support from local government to the project proved instrumental to making it happen – notably in terms of land identification and facilitation. However, while in Vienna this type of housing is embedded in the planning and housing provision system, in Lyon this was not the case, and having political support from the current local administration helped the project to overcome the lack of a suitable policy and legal framework.

Conclusions

This paper has aimed to contribute to the development of an analytical framework that helps to understand collaborations between professional or established housing providers and self-organised resident groups in housing provision for consumption by the latter. We reviewed a range of concepts used in the literature to describe different aspects of these collaborations, and proposed a definition of collaborative housing, as an arrangement where a group of people produce their own housing in full or part in collaboration with established providers.

We developed an analytical diagram to help identify and describe co-production of housing and applied it to a case in Vienna and another in Lyon. This diagram maps the roles of a (leading) group of residents and a number of key partners and the relationships amongst them. Our diagram distinguishes between three types of stakeholders: primary, secondary and those in the wider environment of the project. We classified them according to aspects such as their legitimacy, control of key resources and veto. This allowed us to establish the intensity and relevance of their respective roles and relationships and to compare their relative position across cases. Applying this diagram to a larger number of cases could allow us to identify (any) patterns and to build hypothesis to be tested further.

These partnerships mean a redistribution of roles, where the users occupy a much more central stage than in the past. Beau and Bacque (Citation2010) highlight the need for training of professionals to engage effectively and constructively with the different types of knowledge and competences of residents as one of the key challenges for these initiatives. A number of questions for further research arise regarding the impact of these processes and relationships on each partner, stretching across values, identities and organisational and strategic aspects. Issues of hybridisation of roles and structures as well as the longer term impact of these specific experiences, particularly on professional housing providers, open up a wide scope for further research. The study of co-production in housing, and of the stakeholders taking part in these arrangements, in particular, can provide useful insights to inform both better practices and policies in this field.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the respondents for their valuable input as well as the anonymous reviewers for their feedback, which helped to greatly improve the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. In this paper, we use the term ‘initiative’ in relation to collaborative housing in the sense of a ‘plan or program that is intended to solve a problem’ or the ‘energy or aptitude displayed in initiation of action’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

2. See for example Duivesteijn (Citation2013).

3. Law no 2014-366 of 24 March 2014 ‘Accès au Logement et un Urbanisme Rénové’ – ALUR (law for the access to housing and renewed urbanism, author's own translation).

4. Local government body overseeing subsidised housing construction.

5. ZAC stands in French for ‘Zone d'Aménagement Concerté’, a public development operation zone under the Town Planning Code to substitute for zones to be developed as a priority.

6. A syndic or managing agent in France is both the manager of the building and the regulator of relationships between owners, service suppliers and the insurance company.

7. PLS (‘Prêt Locatif Social’ or social rental housing loan) is available to people on higher incomes relative to the lower-end of social tenants’ income scale.

8. The term ‘very social housing’ (‘logement très social’ in French) refers to social housing allocated to households on very low incomes. In January 2013, the first call for projects PLAI (Prêt Locatif Aide d'Intégration) was launched to encourage the development of a new range of very social housing reserved to households with both financial and social difficulties.

References

- Agranoff, R., & McGuire, M. (2004). Collaborative public management: New strategies for local governments. Georgetown, Washington, DC: University Press.

- Alexander, I., & Robertson, S. (2004). Understanding project sociology by modeling stakeholders. IEEE Software, 21(1), 23–27.

- Alford, J. (1998). A public management road less travelled: Clients as co-producers of public services. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 57(4), 128–137.

- Bauer, E., Czischke, D., Hegedüs, J., Pittini, A., & Teller, N. (2011). Study on social services of general interest: Sector study ‘Social Housing’. Commissioned by the Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, European Commission.

- Biau, V., & Bacqué, M.H. (2010). Habitats alternatifs: Des projets négociés? Paris-Val de Seine: ENSA.

- Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: User and community co-production of services. London: Carnegie Trust and Commission for Rural Community Development.

- Boyle, D., & Harris, M. (2009). The challenges of co-production. How equal partnerships between professionals and the public are crucial to improving public service. London: New Economics Foundation (NEF) & National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA). Retrieved from http://centerforborgerdialog.dk/sites/default/files/CFB_images/bannere/The_Challenge_of_Co-production.pdf

- Bresson, S., & Denèfle, S. (2015). Diversity of self-managed co-housing initiatives in France. Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), 5–16.

- Cahn, E. (2004). No more throwaway people: The co-production imperative. Washington, DC: Essential Books.

- CECODHAS Housing Europe's Observatory. (2012). Impact of the crisis and austerity measures on the social housing sector. Research briefing. Year 5 / Number 2, February 2012. Brussels.

- Chatterton, P., (2013). Towards an agenda for post‐carbon cities: Lessons from lilac, the UK's first ecological, affordable cohousing community. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1654–1674.

- Clarke, J. (2007). Unsettled connections citizens, consumers and the reform of public services. Journal of Consumer Culture, 7(2), 159–178.

- Czischke, D. (2014a). Social housing organisations in England and the Netherlands: Between the state, market and community (unpublished doctoral dissertation). Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands.

- Czischke, D. (2014b). What is the role of housing associations in community-led housing? Learning from good practice in Europe: Final report. Birmingham: DC Consulting.

- Carriou, C. (2012). Toward a new way of providing affordable housing? The Hoche co-operative in Nanterre (France), a case study. Paper presented at the ENHR conference 2012, Toulouse.

- Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society. London: Sage Publications.

- Devaux, C. (2011). Accompagner les projets d'habitat participatif et coopératif. Paris: FNSCHLM - USH.

- Duivesteijn, A. (2013). De Wooncoöperatie: Op weg naar een zichzelf organiserende samenleving. Retrieved from http://www.adriduivesteijn.nl/wp-content/uploads/De-Wooncoöperatie.pdf

- Dunston, R., Lee, A., Boud, D., Brodie, P., & Chiarella, M. (2008). Co-production and health system reform – From re-imagining to re-making. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 68(1), 39–52. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8500.2008.00608.x

- Fenwick, T. (2012). Co-production in professional practice: A sociomaterial analysis. Professions and Professionalism, 2(2), 1–16.

- Flint, J. (2004). The responsible tenant: Housing governance and the politics of behaviour. Housing Studies, 19(6), 893–909.

- Fromm, D. (2012). Seeding community: Collaborative housing as a strategy for social and neighbourhood repair. Built Environment, 38(3), 364–394.

- Fromm, D. (1991). Collaborative communities. Cohousing, central living and other new forms of housing with shared facilities. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Gofen, A. (2015). Citizens’ entrepreneurial role in public service provision. Public Management Review, 17(3), 404–424.

- Gofen, A. (2012). Entrepreneurial exit response to dissatisfaction with public services. Public Administration, 90(4), 1088–1106.

- Heeg, S. (2013). Wohnungen als Finanzanlage. Auswirkungen von Responsibilisierung und Finanzialisierung im Bereich des Wohnens. Sub\ urban. zeitschrift für kritische stadtforschung, 1(1), 75–99.

- Houard, N. (Ed.). (2011). Social housing across Europe. Paris: La Documentation Française.

- Jarvis, H. (2015). Community‐led housing and ‘Slow’ opposition to corporate development: Citizen participation as common ground? Geography Compass, 9(4), 202–213.

- Lafond, M. (Ed.). (2012). CoHousing cultures: Handbuch fur selbstorganisiertes, gemeinschaftliches un nachhaltiges wohnen | handbook for self-organised, community-oriented and sustainable housing. Berlin: Jovis Verlag GmbH.

- Leadbeater, C. (2004). Personalisation through participation: A new script for public services. London: Demos. Retrieved from http://www.demos.co.uk/files/PersonalisationThroughParticipation.pdf

- Leclerc, A. (2013, May 14). A villeurbanne, un « village vertical » comme une alternative à la crise du logement. Le Monde.fr. Retrieved from http://crise.blog.lemonde.fr/2013/05/14/a-villeurbanne-un-village-vertical-comme-une-alternative-a-la-crise-du-logement/

- Lemke, T. (2001). ‘The birth of bio-politics’: Michel Foucault's lecture at the Collège de France on neo-liberal governmentality. Economy and Society, 30(2), 190–207.

- Mathiasen, D.G. (1999). The new public management and its critics. International Public Management Journal, 2(1), 90–111.

- McCamant, K., & Durrett, C. (1988). Cohousing: A contemporary approach to housing ourselves. Berkeley, CA: Habitat Press/Ten Speed Press.

- McGuire, M. (2006). Collaborative public management: Assessing what we know and how we know it. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 33–43.

- McIntyre, Z., & McKee, K. (2012). Creating sustainable communities through tenure-mix: The responsibilisation of marginal homeowners in Scotland. GeoJournal, 77(2), 235–247.

- Minora, F., Mullins, D., & Jones, P. (2012). Governing for habitability. self-organised communities in England and Italy. International Journal of Co-operative Management, 6(2), 33–45.

- Moore, T., & McKee, K. (2014). The ownership of assets by place-based community organisations: Political rationales, geographies of social impact and future research agendas. Social Policy and Society, 13(4), 521–533.

- Moore, T., & Mullins, D. (2013). Scaling-up or going viral? Comparing self-help housing and community land trust facilitation. Voluntary Sector Review, 4(3), 333–354.

- Mullins, D., Czischke, D., & Van Bortel, G. (2014). Hybridising housing organisations.Meanings, concepts and processes of social enterprise. Oxon and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mullins, D. (2006). Competing institutional logics? Local accountability and scale and efficiency in an expanding non-profit housing sector. Public Policy and Administration, 21(3), 6–24.

- Needham, C. (2008). Realising the potential of co-production: Negotiating improvements in public services. Social Policy and Society, 7(2), 221–231.

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy and development. World Development, 24 (6), 1073–1087.

- Ostrom, E., & Baugh, W.H. (1973). Community organization and the provision of police services. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Pache, A.C., & Santos, F. (2013). Embedded in hybrid contexts: How individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 39, 3–35.

- Parker, S. (Ed.). (2013). The squeezed middle: The pressure on ordinary workers in America and Britain. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Parks, R.B. (1981). Consumers as co-producers of public services: Some economic and institutional considerations. Policy Studies Journal, 9(7), 1001–1011.

- Pestoff, V., & Brandsen, T. (2013). Co-production: The third sector and the delivery of public services. Oxon and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Poocharoen, O., & Ting, B. (2015). Collaboration, co-production, networks: Convergence of theories. Public Management Review, 17(4), 587–614.

- Ronald, R., & Elsinga, M. (2012). Beyond home ownership: Housing, welfare and society (housing and society series). London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: Reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sacranie, H. (2011). Strategy, culture and institutional logics: A multi-layered view of community investment at a large housing association (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Birmingham, Birmingham.

- Scanlon, K., Whitehead, C.M., & Fernández Arrigoitia, M. (Eds.) (2014). Social housing in Europe. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 57l–610.

- Sudiyono, G. (2013). Learning from the management and development of current self-organised and community-oriented co-housing projects in Berlin: Making recommendations for the IBA Berlin 2020 (Unpublished master's thesis). Berlin University of Technology, Berlin.

- Thornton, P.H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–129). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tummers, L. (2011). Collectively commissioned housing: New urban qualities through residents self-management. In L. Qu & E. Hasselaar (Eds.), Making room for people: Choice, voice and liveability in residential places (pp. 153–176). Amsterdam: Techne Press.

- Tummers, L. (2016). The re-emergence of self-managed co-housing in Europe: A critical review of co-housing research. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2023–2040.

- Vestbro, D.U. (Ed.). (2010). Living together – Co-housing ideas and realities around the world: Proceedings from the International Collaborative Housing Conference in Stockholm 5-9 May 2010. Stockholm: Division of Urban and Regional Studies, Royal Institute of Technology in collaboration with Kollektivhus NU.

- Walker, R. (1998). New public management and housing associations: From comfort to competition. Policy & Politics, 26(1), 71–87.

- Whitehead, C.M. (2015). From social housing to subsidized housing? Accommodating low-income households in Europe. Built Environment, 41(2), 244–257.