Abstract

This paper examines the role of secondary property ownership (SPO) in Europe (EU). Focusing predominantly on residential properties used as rental-investments, it explores their role in the political economy of housing and welfare, contributing to respectively newer and older literatures about housing wealth and asset-based welfare and the ‘really big trade-off’ between outright homeownership and generous pensions. Both have hitherto largely been viewed as related to ownership of the primary residence. The empirical part of this paper is based on the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), carried out by the European Central Bank in 2014, and providing information about property ownership by samples of households in 20 member states of the EU. The results show that the total wealth held in the form of SPO is considerable while also varying considerably from country to country. SPO held as an investment in the form of landlordism is most prevalent in countries characterised as corporatist-conservative or liberal welfare regimes. In the corporatist-conservative countries, SPO can be seen as a since long established proactive asset-based welfare strategy that compensates for the limitations of their fragmented pension systems, especially for the self-employed. In liberal welfare states, the recent upswing of buy-to-let landlordism is a manifestation of the concentration of housing wealth and limited access to homeownership for starters, which makes SPO an ever more attractive investment.

Introduction

This paper seeks to position secondary property ownership (SPO) in the political economy of housing and welfare. In terms of physical form and use, SPO ranges from holiday homes in rural and coastal areas to buy-to-let apartments in towns and cities, and from weekend homes for those who work in a different location than the residential location of their family to inherited properties in the countryside, sometimes in a different country to the primary residence. Some are simple structures such as chalets or decayed old farms, whereas others are top-end properties in historic city centres. What unites these forms is that they are residential properties that are owned by individuals who may also own a primary residence used as their principal residence.

In recent years, housing scholars have become interested in the characteristics and trends in SPO that link to more general developments in housing markets and housing policy (Aalbers, Bosma, Fernandez, & Hochstenbach, Citation2018; Arundel, Citation2017; Gibb & Nygaard, Citation2005; Paccoud, Citation2017; Soaita, Searle, McKee, & Moore, Citation2017). This is not surprising, as an increasing share of the housing stock fulfils another need than housing for its owner(s), impacting upon the availability and affordability of the housing stock for those searching for a home to live in. Two trends catch the eye. First, there has been recognition of the growth of overseas buyers investing in residential real estate as ‘safe deposit boxes’ (Fernandez & Aalbers, Citation2016), or as lucrative rental investment (Aalbers & van Loon, 2017). Second, there has been a rapid upswing of buy-to-let landlordism in the United Kingdom which has been related to the emergence of a ‘generation rent’ (Lund, Citation2013): here, an increasing share of housing-wealth-rich homeowners is investing in rental housing for an ever-larger group of young people who, due to their precarious employment situation and borrowing constraints, are not able to afford high house prices (Arundel, Citation2017; Mckee, Moore, Soaita, & Crawford, Citation2017).

The rise of SPO, and buy-to-let landlordism in particular, confront housing departments in cities across Europe with a question of justice: is it fair to allow housing market insiders to accumulate additional assets, whilst a combination of precarious labour market conditions and booming house prices obstructs an entry into homeownership for young people? Especially in Britain, but also in the Netherlands, fears have emerged concerning a rise of a new Fuedal order in which those from non-property-owning families have no other choice than handing over a large share of their income to secondary property owners to obtain shelter (Aalbers et al., Citation2018; Walker & Jeraj, Citation2016). However, such analyses lack a comprehensive image of the variety of reasons why individuals obtain secondary properties, and the effect of various types of SPO on the housing market at large. For some individuals, SPO is an intergenerational transfer or a welfare arrangement, whereas it is a general investment for others (Soaita et al., Citation2017). An understanding of the role of SPO in the political economy housing and welfare provides a necessary basis for approaching country specific regulatory interventions that are capable of improving the availability and affordability of housing.

Although there is little comprehensive, harmonised statistical information on the size of SPO in Europe, evidence shows considerable cross-country variation. Most statistical data are derived from ad hoc surveys carried out at individual country, region and even local levels, which is not surprising given that most previous research on SPO has focused on its use for recreation and tourism activities and the impact on the areas in which these properties are located (see e.g., Gallent, Mace, & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2005). Pooling these sources together, it is clear that, at a European level, SPO constitutes a significant share of the total housing stock. In this respect, the Nordic countries appear to take the lead with around 30% of households owning secondary properties (Skak & Bloze, Citation2017). It is also established that a major share of the private rental stock in Europe consists of secondary properties. For example, 60% of the rental housing stock in Germany is in the hands of small-scale private landlords, as opposed to institutional landlords such as pension funds, unions or large investors (Kemp & Kofner, Citation2010). An international comparative perspective is able to reveal the role of secondary property ownership and rental income in countries with different housing regimes and welfare states, explaining how housing alters the socio-economic position of various groups.

The principal aim of this paper is to develop further the links between our understanding of SPO and what might be thought of as mainstream housing research, and specifically with the literature on housing and welfare. In this respect, housing researchers have long pointed to an apparent trade-off between high (outright) homeownership rates and generous public welfare systems (Castles, Citation1998, Kemeny, Citation1981). Albeit with some variation of interpretation, the essence of the trade-off is based on the role of welfare states as providers of so-called ‘transfer capital’ collected by means of compulsory social contributions that for younger households competes with the private accumulation of housing wealth (de Swaan, Citation1989). Older homeowners are less in need of transfer capital (mostly in the form of a generous pension) as their tenure provides them with imputed income (low housing costs in later life) and wealth (possibly used to fulfil welfare needs). These characteristics of homeownership may be considered as the main engine of asset-based welfare, leading, some argue, to the reorientation of welfare states, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries and more recently also in a number of Nordic countries, in a more productivist and neoliberal direction (Lennartz, Citation2017; Malpass, Citation2008; Ronald, Lennartz, & Kadi, Citation2017).

The debate about housing and welfare has focused on homeownership and housing wealth, rather than secondary property ownership, wealth and rental income. SPO is largely absent from these debates although it might also generate wealth, and most notably (rental) income, for its owner. In fact, SPO may have different driving forces among different social groups in different countries. Some might invest in secondary properties because they expect that rental incomes will compensate for their lower pensions in later life, while other households with higher pensions might invest in secondary properties for reasons of consumption or further wealth accumulation (Soaita et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the attractiveness of both strategies can be seen as dependent on the generosity of the welfare state, including institutional support for a second-tier pillar of publicly mandated occupational pensions (De Deken, Citation2018) and on the extent to which the housing regime promotes homeownership and/or fosters house price inflation, both of which contribute to housing wealth accumulation.

A focus on SPO therefore allows us to go beyond understanding of the links between home ownership and welfare, to investigate how the financial position of various socio-economic groups within a welfare state impacts upon their investments in housing beyond primary property ownership. This has added significance in that there may be groups that are comparatively less well-covered by the welfare state that might turn to investments in secondary properties, while at the same time providing other households with rental housing. Further, by linking the housing investments of a share of the population to the trade-off between housing and welfare, it is possible that different forms of SPO not only impact upon the financial situation of their owners, but also on the performance of the housing system as a whole.

This paper begins with a brief review of the literatures on the drivers of SPO, and on the trade-off between housing and welfare, including asset-based welfare, and its variation at different locations and across time periods. It then uses the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), carried out by the European Central Bank (ECB) in 2014 using a representative sample of all households (see ECB, 2016), to provide an examination of SPO and landlordism in Europe. Following presentation of selected features of SPO, it focuses on one form of SPO, landlordism, identifying high rates of landlordism in both conservative-corporatist and liberal regime countries. It then sets out to understand this pattern by examining; firstly, their housing systems and, secondly, the nature of their welfare systems that may have influenced the investment strategies of their households.

Drivers of SPO

A now well-established view of housing is that it constitutes both a consumption good and an investment good. This has been used by Paris (Citation2010) as the basis for classifying the objectives of those pursuing SPO. Relating to this, research on the drivers of SPO has mainly focused on its function as a source of consumption (Gallent et al., Citation2005). Common observations are that people who live in small apartments with limited access to greenery are more likely to own secondary properties, in order to compensate for the characteristics of their living environment (Skak & Bloze, Citation2017), while older, retired people are more likely to own secondary properties in order to enjoy nature at a time in their lives when close proximity to work and urban facilities is less needed (Bieger, Beritelli, & Weinert, Citation2007). Another driver of SPO is the intergenerational support on the housing market. In this case, family members do not buy secondary homes for their own consumption, but for family members to live in. Especially in countries characterised by strongly upward price developments, such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, the affordability of first-time homeownership is structurally undermined. To prevent their offspring to move into – rather expensive – private rental housing, housing-wealth-rich parents increasingly choose to (co-)finance their children’s first steps on the housing ladder (Burrows & Lennartz, Citation2018). Due to the capital gains from their primary residence, these parents can easily out-bid other households in the same housing market segment.

As Paris (Citation2010) indicates, however, some SPO may be pursued equally, or more, because of its investment potential, recognising that this might also take different forms, specifically as (1) wealth investments or (2) rental investments. Secondary properties that belong to the first type (wealth investments) can be purchased solely for that aim (see Fernandez and Aalbers [Citation2016] for a description of housing as ‘safe deposit box’ for the transnational elite), or for a combination of housing consumption and wealth accumulation. The latter category is sub-divided by Paris (Citation2010) into second/multiple homes, pied-à-terres and non-commercial second homes (e.g., investments in housing for studying children).

Secondary properties that belong to the second type (rental investments) are not held for own consumption – for the owner to live in – but for the rental income they generate. Some forms of SPO, such as family support, might represent a middle position as they generate rental income, but are foremost forms of intra-family solidarity. For landlords who purchased secondary properties for their rental income, the literature distinguishes two underlying motivations. First, the stable future (retirement) income flow is pointed out as one of the main reasons (Berry, Citation2000; Kemp & Kofner, Citation2010; Kemp & Rhodes, Citation1997). Investments in rental housing might be a strategy to supplement absent or low second-tier pension arrangements1 by those who are poorly covered by these arrangements. Those who are poorly included in second-tier pension schemes make lower pension contributions, and therefore have more room to invest in secondary properties, while, for the same reason, they also have a higher need for additional income sources in later life (Kemp & Kofner, Citation2010). Secondly, the investment in rental housing might be a strategy to diversify the wealth portfolio of those who are relatively wealthy anyway and well covered by second-tier pension arrangements (see Soaita et al. (Citation2017) and Arundel (2017) for evidence on the nature of buy-to-let in the United Kingdom). The first type of rental investments can be conceptualised as a supplement to second-tier pensions, whereas the second type should be seen as a general investment, or a supplement to the third-tier, that is individual private pensions.

A trade-off between housing and welfare?

Whatever the motives of the owners of secondary property might be, insofar as they are tradable in most circumstances, their properties constitute assets with market values. As such they have the potential to act as assets that can underlie asset-based welfare. Although these assets can be used to buffer all kinds of adverse life course events associated with income falls, they are mostly used to cover income falls after retirement. Exactly how and why asset-based welfare works, depends in part on what type is being considered; here, a distinction has been made between three forms: passive, active and proactive (Doling & Ronald, Citation2010; Ronald & Kadi, Citation2017).

Passive asset-based welfare

The passive form of asset-based welfare is founded on the notion that homeownership forms a supplement to collective welfare arrangements (Ronald & Kadi, Citation2017). On the macro-level, it is argued that countries trade-off between high homeownership rates and generous public welfare arrangements (Castles, Citation1998; Dewilde & Raeymaekers, Citation2008; Kemeny, Citation1981). Castles (Citation1998) narrowed this to a ‘really big trade-off’ between high homeownership rates and generous pension arrangements (instead of welfare arrangements in general), arguing that home owners are less in need of generous pension arrangements as they have low housing costs after retirement when they have amortised the mortgage. Moreover, homeowners have been less keen on supporting the post-World War II (WWII) expansion of the welfare state, as paying taxes directly competes with mortgage amortisation. Traditionally, the passive form of asset-based welfare is dominant in Mediterranean countries (Castles & Ferrera, Citation1996). These countries have small publicly-mandated first-tier pensions, only aimed at alleviating poverty during old age. Second-tier, earnings-related pensions, aimed at preserving the working-life income into old age, are small as well (Ferrera, 1997). As individual contributions to second-tier pensions determine the benefits, a trade-off between homeownership and pension might occur at the individual level as well. In the German-speaking countries, second-tier publicly-mandated pensions are generous for those who had a stable labour marker career. In the Scandinavian countries, the coverage of generous public second-tier is even more universal (Kvist, Citation1999; Schludi, Citation2005). Both the German-speaking and (some) Nordic countries comply with Castles’ ‘really big trade-off’ as they have preserved and developed a large rental sector after WWII. In the case of the German-speaking countries it concerns regulated private rental housing, whereas it concerns public rental or cooperative housing in the case of the Nordic countries.

Active asset-based welfare

‘Active’ asset-based welfare occurs when housing wealth, rather than homeownership per se, is used to finance welfare arrangements. At the micro-level this may be when households liquidate their housing wealth to sustain their livelihood, perhaps by selling the home (and moving to rental housing or a smaller home), or by using advanced financial products such as reverse mortgages to liquidate their housing wealth whilst remaining in their home. Whilst selling the home to liquidate housing wealth happens on a very small scale in all European (EU) countries (Costa-Font, Gil, & Mascarilla, Citation2010), the use of reverse mortgages is restricted to a small sample of countries (Doling & Overton, Citation2007). At the macro-level active asset-based welfare occurs when pension funds engage with mortgage lending. In this situation, high, but indebted, homeownership rates and generous pensions might go hand in hand, as in the Netherlands (Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2008). Macro-level asset-based welfare is a route out of Kemeny and Castles’ dichotomy between countries with high homeownership rates and low pensions, and countries with large rental sectors and generous pensions. Delfani, De Deken, and Dewilde (Citation2015) argue that a combination of a commodified housing system and pension system is a condition for micro-level active asset-based welfare to take place, whereas, for macro-level active asset-based welfare to take place, only housing needs to be commodified. As second-tier pensions are publicly mandated – and therefore decommodified – in nearly all EU countries, micro-level asset-based welfare is only widespread in countries where reverse mortgages are common, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland and Spain (Doling & Overton, Citation2007). In a few other countries, with a finance-led model of homeownership expansion (e.g., the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden), one can find macro-level forms of asset-based welfare. High mortgage debts (between 75% and 115% of the GDP) are mirrored by large pension savings, accumulated in publicly-mandated occupational pension funds. However, a direct link between mortgage debts and pension savings is often lacking. In countries with macro-level asset-based welfare, the role of housing in the pension system has gradually increased (De Deken, Citation2018).

Pro-active asset-based welfare

Underlying both passive and active types of asset-based welfare is the notion that the housing asset involved is the asset held in the form of homeownership. Extending on from this, the ‘proactive’ form occurs when rental income forms a supplement to collective welfare arrangements. In fact, most rental housing in Europe is in the hands of small-scale landlords, owning just a few properties (Kemp, Citation2015). The reasons underlying this are doubtless complex, but two general strategies can be posited: (1) as a means of compensating for low first-tier pensions or exclusion from second-tier pension schemes or (2) as an investment, like any other. In the latter case, it may involve households that can count on generous second-tier pension benefits after retirement, for whom rental investments are a way to diversify their wealth portfolio as a supplement to their third-tier private pensions.

The first of these two strategies may be seen in some conservative-corporatist welfare states where many households invest in real estate often in preference to other types of investments as it is very tangible and considered a high-confidence asset (De Decker & Dewilde, Citation2010). Such investment is often supported by the policy environment. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, for example, rents are relatively regulated in lieu for public subsidies; and this generates stable and predictable returns for investors (Kemp & Kofner, Citation2010), whereas in France and Belgium, homeownership subsidies encourage private households to invest in residential properties (primary residences and secondary properties) rather than other assets. In those conservative welfare states that have stratified status-reinforcing occupational pension schemes, groups that are less-well protected traditionally engaged in landlordism as a supplement to limited first-pillar pensions, and to compensate for limited inclusion in second-tier pensions (De Decker & Dewilde, Citation2010; Soaita et al., Citation2017). This is often the situation facing self-employed workers in conservative welfare states, who have the financial means to invest during working life (given that they often pay lower social contributions), but have low pensions after retirement (Lohmann, Citation2009). Although the classic trade-off theory anticipates that conservative countries have low homeownership rates and generous pension benefits, this evidence indicates the critical significance of the stratified nature of the pension system that may lead to some occupational groups investing in rental housing as second-tier pension arrangement, while providing rental housing for other households. In other words, it is a strategy opposite to the dominant outcome that gives the conservative welfare regime its characteristic shape.

In contrast, the upswing of buy-to-let landlordism in the liberal welfare regime may have very different foundations, more akin to the second strategy. For the United Kingdom, Soaita et al. (Citation2017) indicate that private landlordism and buy-to-let activities are mostly a pure investment strategy, sometimes coupled to intergenerational support. Especially after neo-liberal housing reforms that have privatised social rental housing, deregulated rents and eased access to mortgage finance, house prices are inflated and polarised. This (1) rendered homeownership unaffordable for increasing numbers of young and low- and medium-income households and (2) increased housing wealth inequality (Wind, Lersch, & Dewilde, Citation2017). In combination with ever more precarious work arrangements among young individuals, the rising house prices have boosted the demand for rental housing. As a consequence, investments in housing are more attractive than other investments such as bonds and stocks. Furthermore, the concentration of wealth amongst those who have been able to disproportionally profit from house price gains in recent decades has brought this housing-wealth-rich group into a position to buy additional housing assets, to let out to households who are financially unable to buy (Arundel, Citation2017). A share of investments in rental housing are motivated by intergenerational support, from housing-wealth-rich parents, to housing-poor children (Burrows & Lennartz, Citation2018; Hochstenbach & Boterman, Citation2015). Although letting out apartments to children is generally a non-profit activity, it often involves for-profit elements as well, for example, when the property is simultaneously acquired as a wealth investment, or when additional rental income is generated by (sub)letting to other individuals than their own children. Contrary to those who invest in rental housing in conservative welfare states, buy-to-let landlords in the United Kingdom may be well-covered by second-tier pension arrangements, and their investments can be viewed as providing a supplement to third-tier, private pensions that top up collective-mandated pensions. In some welfare states that are not part of the liberal cluster, such as the Netherlands, a similar upswing of buy-to-let landlordism can be witnessed. Aalbers et al. (Citation2018) point out that especially in the larger cities, where house prices have boomed in recent years, the buy-to-let sector has tripled in size between 2006 and 2016. Due to the tightened eligibility for social rental housing and increased unaffordability of mortgaged homeownership, the demand for private rental housing has increased. Households that made large capital gains during the house price boom are able to enter the market as landlords. Where rental properties are not in the first place a welfare strategy, the supply seems based on a capital surplus finding its route towards realisation.

These recent additions to the debate on the trade-off between homeownership and pensions contribute to our understanding in at least two ways. First, they introduce a more nuanced idea of the nature of public welfare arrangements. Pensions are not just ‘low’ or ‘high’. Instead, there might be large variation regarding the coverage and generosity of first, second and third-tier pensions for different occupational groups. Second, they emphasise the conceptual difference between homeownership-based (passive) welfare and asset-based welfare (active and proactive). The former provides the basis of the classic ‘big trade-off’, especially occurring in countries with more collective but less generous public pension systems or for specific social groups (e.g., the self-employed) that are not well-covered by the pension system. The latter is most likely to occur in situations in which pensions are commodified, giving households room to invest in the way they prefer (Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2015; Lennartz & Ronald, Citation2017; Ronald et al., Citation2017).

Secondary property ownership in Europe

These recent additions to housing debates point to the desirability of developing greater integration between SPO and (the reasons for) landlordism in theories of housing and welfare. In this paper we build insights by drawing on the Household Finance and Consumption Survey that was funded and carried out by the ECB in 2014 and 2015 in 20 EU countries (Austria [AT], Belgium [BE], Cyprus [CY], Germany [DE], Estonia [EE], Spain [ES], Finland [FI], France [FR], Greece [GR], Hungary [HU], Ireland [IE], Italy [IT], Luxemburg [LU], Lithuania <, Malta [MT], the Netherlands [NL], Poland [PL], Portugal [PT], Slovenia [SI] and Slovakia [SK]). The principle aim of the survey is to monitor the financial behaviour of households in the Eurozone, ranging from incomes and expenditures on food, housing, energy, mobility, luxury products, to savings and investments in various forms (bonds, stocks, valuables, etc.). Although the survey is designed to keep an eye on the effects of the central banks’ policies on the economy, the inclusion of several housing-related variables make the data very useful for housing market analyses. Whereas the total sample draws on 50,000 households, those with higher incomes are slightly overrepresented. To overcome the issue of item non-response, and to reduce standard errors, the ECB provides five imputations. The results presented below are calculated with Stata’s multiple imputation package, which generated an average of the coefficients and adjusted standard errors across all five imputations in order to ensure the accuracy of the results.

Secondary property ownership rates

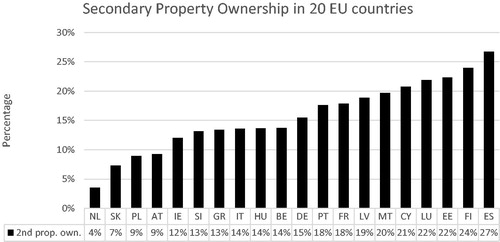

SPO is operationalised as the ownership, in addition to the household’s primary residence, of one or more residential dwellings. Among the 20 countries included in the survey, SPO rates are highest in Finland, Luxemburg, Cyprus, Spain and Estonia, in all of which more than 20% of households own one or more secondary properties in addition to their primary residence (see ). These include countries with a tradition of second homes such as summer cottages (other Scandinavian countries display similar results [see Skak & Bloze, Citation2017]), or countries that are characterised by rapid urbanisation and a family-oriented housing regime. While there are some countries, notably the Netherlands and Slovenia, with quite low rates, the median is 14.5%. Taking account of the different population sizes of different countries, as well as the absence of some EU-countries in the survey, notably the United Kingdom, it seems not unreasonable to conclude that around 15% of EU-households are secondary property owners. In numerical terms alone, therefore, SPO constitutes a not insignificant dimension of the total housing circumstances of EU households and this alone creates considerable potential to contribute to asset-based welfare.

The value of secondary properties

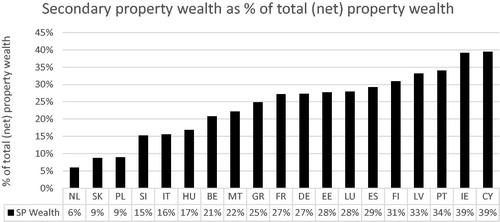

Whereas the numbers are themselves relevant, arguably more so is the fact that many secondary properties will be marketable and therefore have market values that constitute financial assets for individual owners. shows the contribution of secondary property wealth to the total housing wealth in selected EU countries. Secondary property wealth is operationalised as the self-assessed market value of the property minus any outstanding residential mortgage debts. Total housing wealth is operationalised using the same procedure while taking all housing units into account (primary residences and secondary properties). The results indicate that on average, secondary property wealth constitutes a considerable share of total housing wealth in all countries under observation. This confirms the expectation that secondary properties do not comply with the stereotypical small and cheap holiday home: instead they represent a significant source of wealth. Logically, the share of secondary property wealth in total housing wealth is lowest in countries with the lowest rates of secondary property ownership such as The Netherlands, Slovakia and Poland. Secondary property wealth generally takes up a larger share of total housing wealth holdings in countries with higher SPO rates. Interestingly, across the board, the contribution of secondary property wealth to total housing wealth is larger than the share of secondary property owners among homeowners. We point at two explanations. First, a relatively small group of secondary property owners owns a larger real-estate portfolio, representing a far higher value than the primary residence. Second, whereas primary residences are, at least in North-western Europe often financed with mortgages – limiting housing equity, secondary properties are more often owned outright.

Landlordism in Europe

Central to the actual contribution of SPO to asset-based welfare, however, are the motives underlying ownership. Either, households buy secondary properties for consumption purposes, or for investment purposes (rent- or wealth investments). Unfortunately, the survey does not provide a direct means of identifying all categories of SPO, for example distinguishing between second homes used for family holidays and second homes as safety deposit boxes. It does however enable the identification of the incidence of landlordism among secondary property owners, which is operationalised as ownership of two or more housing units, with the household being in receipt of rental income.

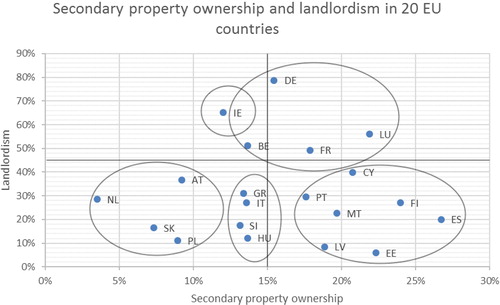

The HFCS data show that there is a high share of landlords among secondary property owners in Ireland, Belgium, Germany, France and Luxemburg (see ). In these countries, more than half of secondary properties are let, with the lead taken by Germany where nearly 80% of secondary properties are being let. These countries can be split into two groups (). One group includes the conservative-corporatist welfare states of France, Belgium, Luxemburg and Germany, characterised by occupationally-fragmented pension provision systems. Austria is the only conservative-corporatist welfare with a slightly lower share of landlords among secondary property owners. A second group includes the only liberal welfare state in the data (Ireland), although from other sources (e.g., Gardiner, Citation2017) the United Kingdom could also be included as anecdotal evidence shows that at least 50% of the secondary properties are let. In both Ireland and the United Kingdom, the public first-tier pension is flat-rate and ungenerous. In both countries, statutory second-tier arrangements are largely absent, with only a privileged part of the workforce covered by (private) occupational welfare arrangements (Berry, Citation2016). In line with older work reporting on similarities regarding the ‘passive’ homeownership-public pensions trade-off in Ireland and Belgium (e.g., De Decker & Dewilde, Citation2010; Delfani et al., Citation2015; Fahey, Citation2003), both countries are also situated near each other in : both are characterised by high outright homeownership rates among the elderly to compensate for ungenerous public first-tier pensions (be it flat-rate in ‘liberal’ Ireland and earnings-related in ‘conservative-corporatist’ Belgium) and limited second-tier pension provision. Whilst both are ‘homeownership countries’, in Ireland homeownership promotion has been of a more ‘universalistic’ (redistributive) nature than in Belgium, where public subsidies continue to explicitly favour middle- to high-income households (Heylen, Citation2015; Norris, Citation2016). Although Belgium is a bit of an outlier with regard to its specific combination of the welfare and housing systems (compared with other conservative-corporatist welfare state it does not have a larger and more strictly regulated rental market), the housing system can nevertheless be denoted as ‘conservative’ (though perhaps less corporatist than in comparison to, for instance, Germany and the Netherlands) as the housing system strengthens the outcomes of the labour market.

In contrast to these two groups, in all other countries with medium rates of secondary property ownership, but lower levels of landlordism, secondary properties are predominantly vacant or used by the family, as holiday homes or to house other members of the extended family. This includes the Mediterranean countries (Spain, Italy, Malta, Greece and Cyprus), post-socialist countries (Estonia, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovenia), and the only representative of the Scandinavian countries: Finland (Roca, Citation2016). Similarly low levels of landlordism among secondary property owners can be expected in the other Nordic countries (Skak & Bloze, Citation2017).

Accounting for patterns of landlordism: housing systems

How can this pattern be explained: why do households in countries with conservative-corporatist and possibly liberal regimes disproportionately rent their secondary properties? One avenue of investigation is founded in the proposition that a key is to be found in the nature of housing systems. They can be described through the pattern of regulation, taxes and subsidies that contribute to the shape of opportunities faced by households. Among other things these opportunities impact upon the balance between social and private rental housing and homeownership. At the same time it is important to stress a caveat that may limit the significance of the explanations based on housing systems, namely that the survey is of households, not of housing stock, so that it is possible for some households to own secondary properties located in countries different from the location of their primary residence.

Homeownership

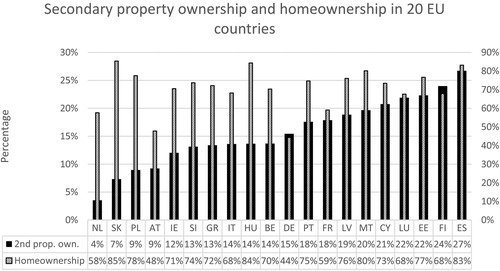

Insofar as one can only own a secondary property if one also owns a primary residence, it might be expected that countries with high rates of homeownership would also have high levels of SPO. Indeed, we find a significant positive relationship between SPO and homeownership rates in the 20 countries under observation (, R = 0.24, P < 0.05). Countries with higher homeownership rates tend to have somewhat higher levels of secondary property ownership as well. To a certain extent this means that institutional arrangements that promote homeownership also translate into significant incentives to own secondary properties. We point at three possible explanations why there is no stronger relationship between homeownership rates and secondary property ownership rates. First, not all arrangements aimed at increasing homeownership are available for those who want to purchase secondary property ownership. The United Kingdom, Denmark, France, Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands have (had) mortgage interest tax deduction, only available for primary residences (Donner, 2000). In countries with stricter planning systems, public authorities provide space for the construction of primary residences rather than secondary properties, especially in times of housing shortage. However, in Germany (a country with low homeownership rates), secondary property ownership is made financially advantageous, as landlordism reduces the shortage of housing (Kemp & Koffner, Citation2010). Second, secondary properties might be located in foreign countries (especially countries of origin and along the Mediterranean coast), which means that international rather than domestic frameworks play a role (Roca, Citation2016). Third, in countries with widespread homeownership, opportunities for letting out properties are limited as only the most marginalised are willing to rent, representing a financial risk for landlords.

Rental sectors

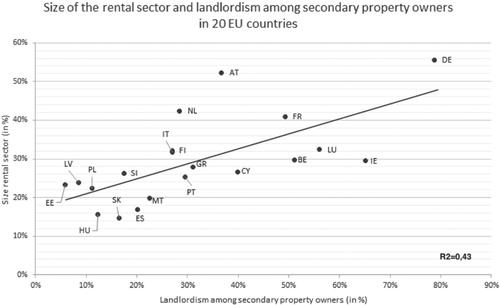

shows a significant positive association (R2 = 0.43) between the size of the rental sector and the percentage of secondary property owners engaging in landlordism. Generally speaking, in countries with a larger rental sector, a higher percentage of secondary property owners use their property to generate rental income. Whereas it is possible for households to own and let dwellings located in another country, this result is consistent with the proposition that in practice most are located in the same country. Following this, landlordism seems to be favoured by at least two different forms of housing market regulation. Firstly, landlordism is attractive in countries with strict overall rent regulations. Although profits might be limited, investments may be stable and profitable due to tax discounts and other subsidies for landlords, and the strong social profile of the tenants (Bourassa & Hoesli, Citation2010). This strategy appears significant in a number of corporatist-conservative welfare states, evidenced by the position of Germany, France and Austria in the upper right-hand quadrant of . Secondly, in liberal welfare states, deregulated rents and deregulated housing finance sit alongside structurally inflated house prices, which impedes the access of younger cohorts to homeownership, boosts the demand for rental housing, and concentrates the housing wealth in the hands of sitting owners, allowing them to use their wealth as collateral for new loans, used to finance buy-to-let properties (Arundel, Citation2017). Gardiner (Citation2017) shows that this phenomenon is a major driver of the recent upswing of SPO in the United Kingdom. Fitting with an apparent liberal regime grouping, Ireland is accordingly located in the upper right-hand quadrant of .

Accounting for patterns of landlordism: welfare regimes

Although the nature of national housing systems, at least the size of rental sectors, appears to influence the pattern of SPO as landlordism, a second avenue of investigation, based on identifying correlations between landlordism rates and forms of welfare provision, arguably provides greater explanatory power.

Employment status

The starting point of the argument here lies with evidence that self-employed people are more likely than salaried workers to own secondary property in the form of rental dwellings (Lohmann Citation2009). Our analysis is limited to the working-age population (below 65 years old), as the HFCS does not provide retrospective information on occupational status. shows that SPO is much more common among self-employed than among salaried workers. For some self-employed, landlordism is their main economic activity, but for most it is a side activity. When the survey results are compared for countries with high rates of landlordism – Belgium, France and Germany – they indicate that self-employed workers are much more likely than salaried workers to let their secondary property or properties). In Luxembourg and Ireland landlordism is equally common for both groups of workers, an outcome that suggests that landlordism might have different drivers in liberal welfare states than in a conservative-corporatist states. In the former, it might be predominantly a strategy for those who may already be reasonably well-off.

Table 1. Secondary property ownership and landlordism among salaries workers and self-employed in 20 European (EU) countries.

The impact of the pension system

Having identified that self-employed people appear to be disproportionately more often the owners of secondary properties generating rental incomes, our challenge here is to establish how this might be grounded in national welfare systems, especially pension systems.

Whereas at a general level pension systems can be seen as a form of horizontal redistribution over the life course (Salas & Rabadan, Citation1998), it is clear that the generosity and structure of pension systems vary considerably across Europe (OECD, 2011). On the basis of information from EU-SILC, we have calculated ‘empirical’ average pension replacement rates by comparing current incomes of (1) the general population and (2) self-employed, and comparing these with the incomes of their retired counterparts. Our calculations show that income replacement rates are relatively low, that is between 40% and 60%, in Ireland, Cyprus, Belgium and Malta, all of which have small public mandatory first-tier pensions, and small (and varying) second-tier pensions. Conservative-corporatist welfare states (except for Belgium, see Delfani et al., Citation2015) are characterised by a multitude of parallel second-tier occupational pension funds that preserve occupational status after retirement. These countries have mediocre pension replacement rates (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). The highest replacement rates are found in as Austria, Poland, Luxembourg and Hungary (between 65% and 90%).

In nearly all countries, replacement rates for the self-employed after retirement are much lower than those for employees. The gap is especially large in some corporatist-conservative welfare states such as Germany, Finland and France, in which the self-employed are not included in the occupational pension funds. In Cyprus, Ireland, Germany and Slovenia, the self-employed face the lowest income replacement rates (between 30% and 45%); in contrast, they face the highest income replacement rates in Lithuania, Luxemburg, Slovakia and Hungary (between 60% and 85%).

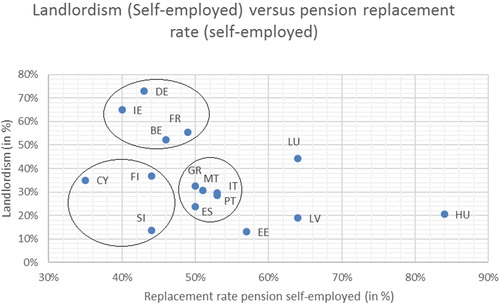

In , countries are positioned on the basis of their pension generosity for the self-employed, and the percentage of landlords among self-employed secondary property owners. The four countries with the highest percentage of landlords among self-employed secondary property owners – Belgium, Germany, France and Ireland – are among those countries with the lowest pension replacement rates. Whereas pensions in Belgium and Ireland are low across the board, in Germany and France pension replacement rates are much lower among self-employed compared to salaried workers. The results are consistent with our proposition that the self-employed may disproportionately engage in landlordism to compensate for their low incomes after retirement in these countries. In Ireland, in contrast, secondary property ownership and landlordism is common among well-off workers. On the basis of evidence from the United Kingdom, showing an upswing of landlordism among housing wealth-rich households (Gardiner, Citation2017), one could assume that similar trends occur generally in liberal welfare states.

In our analysis, there are three countries – Cyprus, Slovenia and Finland – with comparably low pension replacement rates among the self-employed, but in which landlordism among self-employed secondary property owners is relatively uncommon. These are countries in which options for rental are relatively limited, due either to universal homeownership or to a dominance of corporate actors in the rental market. Luxemburg is the only country that combines relatively high pension replacement rates among the self-employed with high levels of landlordism among self-employed secondary property owners, which suggests that rental incomes are received on top of relatively generous pension benefits. Finally, there is a group of Mediterranean countries with moderately generous pension replacement rates, but low levels of landlordism among self-employed secondary property owners.

Poverty relief

In a comparison of 20 EU countries, Lohmann (Citation2009) concludes that the “self-employed are a […] group with a higher pre-transfer poverty risk and a lower probability that poverty will be reduced via transfers” (p. 497). In line with our identification of two groups of countries with high landlordism rates, the overrepresentation of self-employed in SPO and landlordism, then, might be the result of (1) a welfare strategy to supplement low pension incomes, and (2) investment on top of generous pensions.

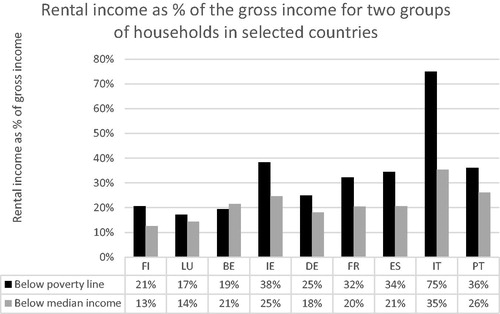

We investigate these possibilities by expressing rent revenues as a percentage of the gross income (net income is not available in the HFCS). We compare two groups: those with an income below the poverty line, and those with an income below the median income. Following Eurostat (Citation2017), the relative poverty threshold is defined as 60% of the national median equivalised income. shows that rental incomes constitute a considerable source of income for households that live below the poverty line (based on their gross income). In those countries with high levels of landlordism (Germany, France, Luxemburg, Ireland and Belgium), rental revenues boost the incomes of poor households with 15%–35%. In countries with lower rates of landlordism, such as Italy, Spain and Portugal, these figures are even larger. Additionally, further indicates that rental incomes boost the incomes of below-median income households by 10%–25% (somewhat less than among those living below the poverty line). In a large number of cases, the rental revenues allow the landlords to pass the median income threshold, and to afford a somewhat more ‘elevated’ life-style. The results provide evidence supporting the proposition that in conservative-corporatist welfare states, the self-employed and those who are poorly covered by the pension system strongly rely on the revenues from landlordism to sustain their livelihood after retirement.

To summarise, then, there are two country clusters with relatively high levels of secondary property ownership in which secondary properties fulfil different roles. First, there are countries in which landlordism is dominant. In these countries (Germany, France, Luxemburg, Ireland and Belgium) landlordism mitigates old-age poverty for groups that are not well protected by the welfare state, such as the self-employed. Landlordism has a different driver for the corporatist-conservative welfare states (where landlordism has been a common strategy to supplement a lower income in later life for decades) and the liberal welfare states (where it is a relatively new phenomenon). In the latter, it is relatively skewed toward property speculation by relatively wealthy, but not necessarily self-employed, homeowners already supported by relatively generous pensions, whereas in the former landlords are predominantly self-employed workers who are largely excluded by – otherwise relatively generous – second-tier pension arrangements.

Discussion

Although the rate varies from country to country, and allowing for the particular sample available, our analysis suggests that, overall, around 15% of households in the EU own secondary properties. Together, such properties thus constitute a significant share of the total EU housing stock. Furthermore, it can be expected that many will be tradable and thus have market values. Again, there are large country differences. Even though they might not, on average, have values as high as primary properties, they do constitute a significant share of individual household – individual country – and total EU housing wealth.

These figures point to a limitation of housing policy analysis that focuses solely on primary residences, and especially analysis that attempts to link the significance of housing assets, housing market behaviour, and the wider political and economic environment. They also support the principal objective of this paper of exploring the ways in which SPO relates to longstanding debates in the housing studies literature summarised under the heading of ‘the really big trade-off’ between homeownership and pensions, and more recent debates about asset-based welfare.

In pursuing this objective, the distinction between consumption and investment motives is a useful starting point. However, this distinction is not hard: for example, buyers of second homes intended for family holidays may, at the same time, also be making an investment that will provide a positive return. Nevertheless, the identification of SPO that produces rental payments and, as such constitutes dwellings let by private individuals, brings together properties that are not intended for consumption by the owner. In that sense it seems reasonable to view them as a sector of SPO that is an investment, has a financial value as an asset, and contributes to the wealth and spending power of owners. In turn, this has similarities with the assets embedded in primary properties, and is thus potentially a factor in both the trade-off and asset-based welfare.

The aim of our analysis, then, has been to use survey data, aggregated at the country level, to identify which countries have a high rate of SPO used as rental properties and which low, as the first step to accounting for that variation in terms that link with debates about a housing asset-welfare trade-off.

Examination of the co-occurrence of SPO and landlordism indicates a number of country groupings. The majority of countries in our sample have rather low proportions of their SPO sectors that are rented out and it seems likely that many – especially those in the Mediterranean countries for example – are heavily skewed toward consumption-led SPO in the form of holiday homes or housing provision for the extended family. But, two groups of countries stand out for their orientation toward landlordism among secondary property owners. First, it concerns countries with high levels of both SPO and landlordism, namely Germany, France, Belgium and Luxembourg. Second, it concerns countries with moderate levels of SPO but high rates of landlordism in liberal countries such as Ireland (and presumably the United Kingdom). Unfortunately the United Kingdom is absent from our data set, but the evidence from elsewhere (Gardiner, Citation2017) supports a conclusion that, in terms of welfare regime typologies, landlordism forms a major part of SPO sectors in both liberal and conservative-corporatist regimes, but does not do so in Mediterranean, social democratic and post-communist welfare regimes.

How can this pattern be explained and how does it relate to our concern with the literature about trade-off and asset-based welfare? One avenue of investigation is founded in the proposition that a key is to be found in the nature of housing systems, even while recognising that the incidence of SPO is related to households rather than national housing stocks. Nevertheless, it might be expected that countries with high rates of homeownership would also have high levels of SPO, because one can only own a secondary property if one also owns a primary residence. But, our evidence indicates that at the country level the two are not related. It might also be expected that landlordism will be high as a proportion of SPO in countries in which the housing system supports large rental sectors. Here, the relationship is positive and significant, and, moreover, the cluster of conservative-corporatist regime countries – Germany, France, Austria, Luxembourg but less so Belgium – is again identifiable.

Another avenue of investigation, one that arguably provides greater leverage on our trade-off and asset-based welfare interests, is based on exploring correlations between landlordism and measures of welfare. The key observation here is that in countries where there is a high share of landlords among SPO, a high proportion of SPO is held by people who are self-employed. The significance of this lies in the fact that in many countries, especially among those with corporatist-conservative welfare systems, self-employed people have less generous pension arrangements than those who are employed. In fact, the stream of rent that landlords get from their properties appears to lift many out of poverty. This supports a conclusion that especially in conservative-corporatist countries, those who are self-employed and poorly covered by national pension systems, strongly rely on the revenues from landlordism to supplement their incomes.

In contrast, in liberal regimes where landlordism has recently increased significantly it appears to be related less to self-employment, and exclusion from pension provision but may rather be a strategy adopted by relatively high wealth homeowners further enhancing their wealth through property investment. In these countries, the inaccessibility of homeownership for younger households (with a lower socio-economic status) pushes many to become tenants and puts housing-wealth-rich households in a favourable position to diversify their wealth portfolio.

Conclusion

There are a number of general conclusions that can be drawn from these findings. Firstly, welfare states do not protect different social and occupational groups equally well against the risks of income loss in old age. This has been extensively argued with respect to the position of women in many welfare systems (Mandel, Citation2012; Orloff, Citation1993). This argument can be extended to some self-employed people, as they have been treated less favourably as well (Lohmann, Citation2009). Welfare state arrangements are the outcome of a democratic class struggle, in which labour unions have aimed to preserve and protect the socio-economic status of employees (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). In many cases, the self-employed face less social protection, as they are considered employers rather than employees, despite their income level. Therefore, in corporatist-conservative welfare states with generally well-developed social insurance systems, the self-employed mainly rely on public first-tier pension arrangements. They are barely included in occupation-based and fragmented publicly-mandated second-tier pension arrangements due to the stratified, salary-based nature of the system. Whereas it is common for salaried workers in corporatist-conservative welfare states to opt for rental housing as they have their pensions arranged collectively, previous research did not point out how this alleged macro-level trade-off between homeownership and pensions affects the self-employed. The results show that the self-employed might opt for homeownership and landlordism, as they are not included in these collective arrangements. Their rental income is a large share of their pension, whereas those who are well included in the system occupy the properties they let.

Secondly, many discussions about asset-based welfare and about the ‘really big trade-off’ have focused on the position of homeowners. Our analysis provides further evidence that the rental income from secondary properties also has potential to influence people’s welfare position and thereby to figure in their wider strategising. For those with small second-tier pension arrangements, rental income may be an essential supplement to the old-age income, especially in corporatist-conservative welfare states. Another type of SPO that is less related to the provisioning of welfare has gained importance recently: especially in liberal welfare states, with unregulated rental markets, those who have profited from rising house prices invest in buy-to-let properties. A share of these investments can be considered as intergenerational support from parents to children whose opportunities to enter homeownership are diminished due to house price surges. Another share of these investments is purely speculative. As most of the housing-wealth-rich households that invest in rental properties are well covered by second-tier pension arrangements, their rental incomes can be considered a general investment strategy, or at most as a supplement to third-tier pensions.

Thirdly, landlordism appears to have been a linchpin in the conservative-corporatist welfare regime from the outset, providing a crucial means whereby the needs of two groups of citizens could be met: those in need of a stable income flow in old age (the self-employed), and those in search of affordable rental housing (employed workers). Whereas the surge of buy-to-let seems to be a recent and current trend in advanced economies, it is especially the speculative (Anglo-Saxon) form that is new. However, this form is not limited to Anglo-Saxon countries. In other countries with comparable house price gains, such as the Netherlands, a similar upswing of speculative buy-to-let can be witnessed (Aalbers et al., Citation2018). The traditional form of SPO and landlordism has been a feature of conservative-corporatist welfare states for many decades. The sustainability of the traditional buy-to-let model in the corporatist-conservative welfare states depends on house price gains that might incentivise housing-wealth-rich individuals to enter the market, and the stability of the income of salaried workers (determining the demand), and the self-employed (determining the traditional supply).

Finally, future research, based on more robust data, should determine the importance of rental income for the self-employed in a wider range of situations, as both buy-to-let landlordism and self-employment increase rapidly (Barbieri, Citation2009). Many ‘new’ forms of self-employment are however more precarious than before, and might not allow these new groups to proactively invest in secondary property as a strategy to complement future pension income with a rental income stream (De Deken, Citation2018). The HFCS data used in this paper could not shed light on these issues due to several shortcomings, related to its one-sided focus on the financial behaviour of households in the Eurozone. First, the sample contains a relatively small group of secondary owners and self-employed. Second, the survey does not include many questions about the housing practices of secondary property owners. As landlordism appears to have different drivers in liberal and conservative-corporatist welfare states, it is essential to include the motives for owning secondary properties in the analysis (e.g., intergenerational support, pension arrangement, general investment). Third, to shed light on the trade-off between homeownership/secondary property ownership and pension generosity on the micro level, more information is needed on the individual pension savings and expected generosity of second-tier pension schemes. Finally, more detailed information on housing tenure (e.g., distinguishing social rental housing from private rental housing provided by small-scale and professional landlords), would allow to better map the social profile of the tenants living in secondary properties bought as rental investment. Nevertheless, secondary property ownership may increasingly become a marker of economic inequality, deserving more attention from housing scholars and policy makers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 First-tier pensions are generally publicly provided through Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) schemes in which the current working population provides current retirees with a pension, aimed at the prevention of poverty during old age. Second-tier pensions are generally publicly mandated (private) funds in which employees collectively save for their pension in order to prevent income falls after retirement. Third-tier pensions are private schemes through which individuals can save for supplementary pensions (De Deken, Citation2018).

References

- Aalbers, M., Bosma, J., Fernandez, R., & Hochstenbach, C. (2018). Buy-to-let gewikt en gewogen. Retrieved from https://www.sp.nl/sites/default/files/onderzoek_buy_to_let_0.pdf

- Arundel, R. (2017). Equity inequity: Housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the rise of private landlordism. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(2), 1–25.

- Barbieri, P. (2009). Flexible employment and inequality in Europe. European Sociological Review, 25(6), 621–628. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp020

- Berry, M. (2000). Investment in rental housing in Australia: Small landlords and institutional investors. Housing Studies, 15(5), 661–681. doi:10.1080/02673030050134547

- Berry, C. (2016). Austerity, ageing and the financialisation of pensions policy in the UK. British Politics, 11(1), 2–25. doi:10.1057/bp.2014.19

- Bieger, T., Beritelli, P., & Weinert, R. (2007). Understanding second home owners who do not rent – Insights on the proprietors of self-catered accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(2), 263–276. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.10.011

- Bourassa, S. C., & Hoesli, M. (2010). Why do the Swiss rent? The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 40(3), 286–309. doi:10.1007/s11146-008-9140-4

- Burrows, V., & Lennartz, C. (2018). The timing of intergenerational transfers and household wealth: Too little, too late? Retrieved February 8, 2019 from http://www.iariw.org/copenhagen/burrows.pdf

- Castles, F. G., & Ferrera, M. (1996). Home ownership and the welfare state: is Southern Europe different? South European Society and Politics, 1(2), 163–185.

- Castles, F. G. (1998). The really big trade‐off: Home ownership and the welfare state in the new world and the old. Acta Politica, 33(1), 5–19.

- Costa-Font, J., Gil, J., & Mascarilla, O. (2010). Housing wealth and housing decisions in old age: Sale and reversion. Housing Studies, 25(3), 375–395. doi:10.1080/02673031003711014

- De Decker, P., & Dewilde, C. (2010). Home-ownership and asset-based welfare: The case of Belgium. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 243–262. doi:10.1007/s10901-010-9185-6

- De Deken, J. (2018). Towards a comprehensive explanation of the development of occupational pension. The interplay between welfare state legacies, industrial relations, and housing regimes in Belgium and the Netherlands. Social Policy & Administration, 52(2), 519–533. doi:10.1111/spol.12381

- Delfani, N., De Deken, J., & Dewilde, C. (2015). Poor because of low pensions or expensive housing? The combined impact of pension and housing systems on poverty among the elderly. International Journal of Housing Policy, 15(3), 260–284. doi:10.1080/14616718.2015.1004880

- De Swaan, A. (1989). Zorg en de staat. Welzijn, onderwijs en gezondheidszorg in Europa en de Verenigde Staten in de nieuwe tijd. Amsterdam: Bakker.

- Dewilde, C., & Raeymaekers, P. (2008). The trade-off between home-ownership and pensions: Individual and institutional determinants of old-age poverty. Ageing & Society, 28(6), 805–830. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007277

- Doling, J., & Overton, L. (2007). The European Commission's Green Paper: reverse mortgages as a source of retirement income. Retrieved February 8, 2019 from https://piu.org.pl/public/upload/ibrowser/WU/WU3_2010/doling-overton.pdf

- Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (2010). Home ownership and asset-based welfare. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 165–173. doi:10.1007/s10901-009-9177-6

- Elsinga, M. G., & Hoekstra, J. S. C. M. (2015). The Janus face of homeownership-based welfare. Critical Housing Analysis, 2 (1), 1. doi:10.13060/23362839.2015.2.1.174

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Eurostat (2017). Statistics Explained. Income distribution statistics. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Income_distribution_statistics

- Fahey, T. (2003). Is there a trade-off between pensions and home ownership? An exploration of the Irish case. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(2), 159–173. doi:10.1177/0958928703013002004

- Fernandez, R., & Aalbers, M. B. (2016). Financialization and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Competition & Change, 20(2), 71–88. doi:10.1177/1024529415623916

- Gallent, N., Mace, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2005). Second homes: European perspectives and UK policies. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Gardiner, L. (2017). Home sweet home – The rise of multiple property ownership in Britain. Retrieved from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/blog/homes-sweet-homes-the-rise-of-multiple-property-ownership-in-britain/

- Gibb, K., & Nygaard, C. (2005). The impact of buy to let residential investment on local housing markets: Evidence from Glasgow, Scotland. International Journal of Housing Policy, 5(3), 301–326. doi:10.1080/14616710500342218

- Heylen, K. (2015). De verdelende impact van de woonsubsidies. In De Decker, P., Meeus, B., Pannecoucke, I., Schillebeeckx, E., Verstraete, J. & Volckaert, E. (Eds.), Woonnood in Vlaanden. Feiten, mythen, voorstellen (pp. 471–488). Antwerpen-Apeldoorn: Garant.

- Hochstenbach, C., & Boterman, W. R. (2015). Navigating the field of housing: Housing pathways of young people in Amsterdam. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 30(2), 257–274. doi:10.1007/s10901-014-9405-6

- Kemeny, J. (1981). The myth of home ownership. London: Routledge.

- Kemp, P. A. (2015). Private renting after the global financial crisis. Housing Studies, 30(4), 601–620. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1027671

- Kemp, P. A., & Kofner, S. (2010). Contrasting varieties of private renting: England and Germany. International Journal of Housing Policy, 10(4), 379–398. doi:10.1080/14616718.2010.526401

- Kemp, P. A., & Rhodes, D. (1997). The motivations and attitudes to letting of private landlords in Scotland. Journal of Property Research, 14(2), 117–132. doi:10.1080/095999197368672

- Kvist, J. (1999). Welfare reform in the Nordic countries in the 1990s: using fuzzy-set theory to assess conformity to ideal types. Journal of European Social Policy, 9(3), 231–252. doi:10.1177/095892879900900303

- Lennartz, C. (2017). Housing wealth and welfare state restructuring: Between asset-based welfare and the social investment strategy. In: Dewilde C. and Ronald R. (Eds.), Housing Wealth and Welfare (pp. 108–131). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Lennartz, C., & Ronald, R. (2017). Asset-based welfare and social investment: Competing, compatible, or complementary social policy strategies for the new welfare state? Housing, Theory and Society, 34(2), 201–220. doi:10.1080/14036096.2016.1220422

- Lohmann, H. (2009). Welfare states, labour market institutions and the working poor: A comparative analysis of 20 European countries. European Sociological Review, 25(4), 489–504. doi:10.1093/esr/jcn064

- Lund, B. (2013). A ‘property owning democracy’or ‘generation rent’? The Political Quarterly, 84(1), 53–60. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2013.02426.x

- Malpass, P. (2008). Housing and the new welfare state: Wobbly pillar or cornerstone? Housing Studies, 23(1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/02673030701731100

- Mandel, H. (2012). Winners and losers: The consequences of welfare state policies for gender wage inequality. European Sociological Review, 28(2), 241–262. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq061

- Mckee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A., & Crawford, J. (2017). ‘Generation rent’and the fallacy of choice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 318–333. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12445

- Norris, M. (2016). Varieties of home ownership: Ireland’s transition from a socialised to a marketised policy regime. Housing Studies, 31(1), 81–101. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1061107

- Orloff, A. S. (1993). Gender and the social rights of citizenship: The comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. American Sociological Review, 58(3), 303–328. doi:10.2307/2095903

- Paccoud, A. (2017). Buy-to-let gentrification: Extending social change through tenure shifts. Environment and Planning A, 49(4), 839–856. doi:10.1177/0308518X16679406

- Paris, C. (2010). Affluence, mobility and second home ownership. London: Routledge.

- Roca, Z. (Ed.). (2016). Second home tourism in Europe: Lifestyle issues and policy responses. London: Routledge.

- Ronald, R., Lennartz, C., & Kadi, J. (2017). What ever happened to asset-based welfare? Shifting approaches to housing wealth and welfare security. Policy & Politics, 45(2), 173–193. doi:10.1332/030557316X14786045239560

- Salas, R., & Rabadan, I. (1998). Lifetime and vertical intertemporal inequality, income smoothing, and redistribution: A social welfare approach. Review of Income and Wealth, 44(1), 63–79. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.1998.tb00252.x

- Schludi, M. (2005). The reform of Bismarckian pension systems: A comparison of pension politics in Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Sweden. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Schwartz, H., & Seabrooke, L. (2008). Varieties of residential capitalism in the international political economy: Old welfare states and the new politics of housing. Comparative European Politics, 6(3), 237–261. doi:10.1057/cep.2008.10

- Skak, M., & Bloze, G. (2017). Owning and letting of second homes: What are the drivers? Insights from Denmark. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 693–712. doi:10.1007/s10901-016-9531-4

- Soaita, A. M., Searle, B. A., McKee, K., & Moore, T. (2017). Becoming a landlord: Strategies of property-based welfare in the private rental sector in Great Britain. Housing Studies, 32(5), 613–637. doi:10.1080/02673037.2016.1228855

- Walker, R., & Jeraj, S. (2016). The rent trap: How we fell into it and how we get out of it. London: Pluto Press.

- Wind, B., Lersch, P., & Dewilde, C. (2017). The distribution of housing wealth in 16 European countries: Accounting for institutional differences. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 625–647. doi:10.1007/s10901-016-9540-3