Abstract

This article investigates the ways in which the structure of the private ownership of property affects the operation of land and housing markets. It draws on detailed Land Registry data to identify the types of actors found at the top of the property wealth distribution in Dudelange, Luxembourg, and to gauge their respective influence on the production of the residential environment. While the top tail is made up of property developers, landowners and super-landlords, an analysis of the planning and land assembly processes for six large scale residential developments in the city since the 1970s shows that the production of housing is driven by a small group of tightly interconnected private landowners and property developers. The level of property wealth concentration in a given territory is thus not innocuous – it affects the production of the residential environment, especially when multiple property ownership is interlinked with the concentrated control over residential land. The study complements discussions on the relation between property, wealth and the production of housing that focus on homeowners, small-scale private landlords and the super-rich (on the consumption side) and, on the production side, on selected actors such as financialised property developers and public landowners.

Introduction

This article is an exploratory investigation of the influence of top property owners on the land and housing markets in the context of the re-concentration of (property) wealth (Piketty, Citation2014). It focuses on the case of Luxembourg, a country with very low property taxes, no inheritance tax on transfers in direct line and which has experienced rapid house and land price increases over the last decades (BCL, Citation2015; ODH, Citation2019a). Drawing on an archive of property transactions for the municipality of Dudelange since 1949 provided by the Land Registry, this study aims to complement the existing literature on the relation between housing and wealth by shifting the focus of analysis away from the ‘wealth middle classes’ to which property wealth is usually attached. The notion of the ‘wealth middle class’ (Piketty & Saez, Citation2014, p. 839) captures the major innovation of the 20th century as concerns the distribution of wealth: it was the first time that the middle classes had been able to accumulate wealth holdings, mostly in the form of the ownership of the household’s main residence. As other papers in this special issue demonstrate, belonging to the wealth middle class increasingly also involves the ownership of additional homes, i.e., the appropriation of multiple property ownership.

However, instead of a focus on the wealth middle class, this article is concerned with the ways in which the structure of the private ownership of property in a particular territory – and particularly the percentage of total property wealth held by the top percentiles of owners – affects the operation of land and housing markets. In examining multiple property ownership, the article thus shifts from the middle to the top tail of the property wealth distribution. It shows how multiple property ownership – when it involves the control over residential land – becomes a central force in the production of the residential environment. This will be shown by mobilising Land Registry data on the property holdings of private actors at the top of the local property wealth hierarchy to track the ways in which they have been involved in the production of the residential environment. In relation to the literature on the links between property wealth and the operation of land and housing markets, this can usefully complement consumption side studies focused on owner occupiers and, more recently, on small-scale landlords and the transnational wealth elite and start to broaden out production side studies that have so far centred on the financialisation of property development and on the actions of public landowners.

The article first sets the scene by providing a discussion of the ways in which the links between property, wealth and the production of housing have been studied in the literature. The focus then moves to a short presentation of the Luxembourgish context and of the case study area: a former industrial town in the relatively deprived South which has seen a recent resurgence. This is followed by the analysis of the relative importance of the three types of actors that make up the top tail of the property wealth distribution in Dudelange: property developers, landowners and super-landlords. As described in a later section, all of these actors have estimated property wealth holdings of over 3 million euros. What distinguishes them is their involvement in the development of houses and apartment buildings (property developers) and the type of property good that makes up the majority of the estimated value of their holdings: houses and apartments (super-landlords) or land (landowners). These types of actors emerged from an exploratory analysis in a particular city, but seem to converge with the categories mobilised in the literature. Drawing on an analysis of the role of these actors in the planning and land assembly for six large scale residential developments in Dudelange since the 1970s, the article then identifies a small set of tightly connected landowners and property developers at the very top of the property wealth distribution who have been able to expand their property wealth through the control of the production of the residential environment.

Property, wealth and the production of housing

The top of the property wealth distribution is at the cross-roads of a number of disciplinary debates. In work on wealth inequality, Piketty (Citation2014) has developed an account in which the development of wealth inequalities focuses on macro-economic drivers and is synthesised by the r > g inequality: wealth inequality tends to increase whenever the return on capital r (linked to the level of taxation) is greater than the rate of growth (of population and productivity) g. His account draws on the existence of unequal rates of return on wealth between the average wealth holder and those at the top of the wealth hierarchy. This difference in rates of return is linked to different wealth portfolio compositions, with property wealth (understood as the ownership of the household’s main residence) found to be the major source of wealth for the majority of the population, what has been called the ‘wealth middle class’ (Piketty & Saez, Citation2014).

Research on housing and wealth has followed this identification of housing as middle class wealth, with attention focused on three broad issues. The first is on the role of housing inheritance, and of its uneven geographical distribution, for wealth distribution (Forrest & Murie, Citation1989; Hamnett, Citation1992), with recent studies highlighting the importance of parental background for purchases in expensive housing markets (Coulter, Citation2017; Hochstenbach, Citation2018). The second concerns the implications of changing homeownership rates for the evolution of wealth inequality (Hamnett, Citation1991; Thorns, Citation1989). Recent studies have highlighted the way in which this can be mediated by the different housing regimes in Europe (Wind, Lersch, & Dewilde, Citation2017) or how rising homeownership affects the spatial distribution of wealth in Canadian cities (Walks, Citation2016). The third focus is the way in which geography intersects with housing wealth. It has been shown that the value of a property is inseparable from the neighbourhood in which the property is located (Forrest & Murie, Citation1989) and that it also depends on the way in which the area, and the wider territory it is a part of, changes (Badcock, Citation1994). It has been shown for owner-occupation that gains associated with property ownership are not equal across a territory (Kim, Citation2003; Murie, Citation1991; Thomas & Dorling, Citation2004) and that higher socio-economic groups are better able to take advantage of these differentials (Burbidge, Citation2000; Hamnett, Citation1999; Wind & Hedman, Citation2018).

Recent studies have taken stock of the re-concentration of property wealth within the ‘wealth middle classes’ and have centred their analyses on the return of small-scale landlordism. Ronald and Kadi (Citation2018) provide a detailed analysis of the rise of private landlords that underlies the recent return of private renting in the UK. While this is undoubtedly a development with broad implications – such as the rise of buy-to-let gentrification (Paccoud, Citation2017), it is driven by small-scale landlords who own one or two properties as letting investments. Arundel (Citation2017), drawing on the Wealth and Assets Survey, finds that these landlords are overwhelmingly found in the top housing wealth deciles. This provides some justification for the distinction operated in the analysis below between super-landlords (those at the top of the property wealth distribution) and small-scale landlords.

There are, however, elements in the literature which point to the importance of investigating top property wealth holders in their own right. Benton, Keister, and Lee (Citation2017), in the most detailed description of the top owners of real estate wealth to date (based on the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) in the United States) report very little overlap between the top real estate owners and the households with the highest net worth (Benton et al., Citation2017: 59). Second, the variables that explain the possession of real estate wealth for the survey population as a whole (receiving an inheritance, being highly educated, being white, etc.) are not found to be significant in explaining a household’s situation in the top 1% of real estate holders (Benton et al., Citation2017: 60).

A strand of research which sheds some light on the actors at the top of the property wealth distribution is the work that seeks to understand the real estate investments of the super-rich, pushed forward by Beaverstock, Hubbard, and Short (Citation2004) and Hay and Muller (Citation2012). Focusing on London, Atkinson, Burrows, and Rhodes (Citation2016) show how the city has become a magnet for residential investments by this population and chart the implications of the internationalisation of the property market that follows. Paris (Citation2017) provides details on the transnational residential investment strategies of the super-rich through the case of Asian investments in Australia. There have been some attempts to link these transnational investments into real estate to the literature on the financialisation of housing. For example, Fernandez, Hofman, and Aalbers (Citation2016) show that particular cities such as New York and London have become ‘safe deposit boxes’ for the transnational wealth elite linked to the growing ‘wall of money’ searching for investment opportunities (van Loon & Aalbers, Citation2017). These new developments indicate that the consumption of housing is no longer limited to the wealth middle class.

What unites all of the research at the intersection of housing and wealth presented thus far is that it is primarily concerned with the consumption of housing and its unequal distribution. The analyses in this paper are an attempt to push the discussion towards the ways in which the structure of the ownership of property in a given territory shapes the production of the residential environment. As concerns the production of the residential environment, there seem to be two main lines of engagement: the financialisation of property development and the actions of public landowners. Examples of work on property developers include Pollard (Citation2009) that compares the development of housing production systems in France and Spain, van Loon (Citation2016) that contrasts the financialisation of real estate development in the Netherlands to the ‘patient capital’ approach of Belgian developers and Romainville (2017), who provides a detailed study of the ways in which capital from other economic spheres enters the housing market through property development in Brussels. Other studies focus on the ways in which financialisation shapes the production of the built environment: Guironnet, Attuyer, and Halbert (Citation2016) show how the expectations of investors for a large-scale redevelopment scheme constrained the local authority in its strategic plans for the area; Sanfelici and Halbert (Citation2016) provide an account of the way in which the relation between investors and property developers in Brazil shapes the production of housing.

The second line of research into the production of the residential environment concerns the actions of usually large public landowners, pushed forward by Christophers’ (2016) work on the political economy of land. This work shows the significant effects of the privatisation of public land on the type of housing produced: Hyötyläinen and Haila (Citation2018) show how the sale of public land to an investment company led to the development of an ‘island of extreme wealth’, and Adisson and Artioli (Citation2019) show how different institutional arrangements shape the on-the-ground results of the sale of land by public landowners in France and Italy. This research strand is also concerned with the other ways in which public landowners can influence the housing and commercial markets. For example, Christophers (Citation2019) describes the strategies used by austerity-squeezed local authorities in England to mobilise property development and ownership to maintain essential services.

This paper fills a research gap by focusing on the influence of a variety of private actors at the top of the property wealth distribution on the production of the residential environment. This can usefully complement the work described above which discusses the changing distribution of housing consumption within the ‘wealth middle classes’ and the housing consumption behaviours of the super-rich linked to the of ‘wall of money’ flowing into real estate. It is also an attempt to broaden out discussions on the actors involved in the production of the residential environment, which has so far focused on financialised private developers and public landowners. This will be done by presenting the structure of private property ownership in Dudelange, identifying the three types of private actors present at the top of the property wealth distribution – property developers, landowners and super-landlords – and by gauging the influence of these top property owners on six large scale residential projects that took place in the city since the end of the 1970s. The literature presented above provides some indication that the actors identified through an exploratory analysis of the top of Dudelange’s property wealth distribution are in line with the actors studied in the broad housing and wealth literature.

The structure of property ownership in Dudelange

Presentation of Luxembourg and Dudelange

Luxembourg is a particularly interesting case for investigating property wealth inequality and top property wealth owners. While 69% of households own the property in which they live, there are significant disparities in property prices across the country’s territory (ODH, Citation2016) and socio-spatial differentiation is marked (ODS, Citation2013). There are also large inequalities regarding multiple property ownership (Osier, Citation2011; Ziegelmeyer, Citation2015). For example, drawing on HFCS data, Ziegelmeyer (Citation2015: 17) reports that the share of rental income from multiple property ownership is just over 10% in the fifth quintile of wealth owners, while it is at 1.1% for the fourth and well below 1% for the first three quintiles. These inequalities have developed in a context in which house prices have increased by close to a factor of 3.5 between 1995 and 2014, just behind the UK and Sweden (BCL, Citation2015, p. 112). The data in Cowell, Nolan, Olivera, and Van Kerm (Citation2017) show that in Luxembourg property represents a similar share of net worth at both the aggregate level and for the 5% wealthiest in their sample (85% and 84%, respectively). This is in contrast to drops of at least 10 percentage points when moving from the aggregate to the top 5% level in this share for the other seven OECD countries studied. The general tendency for the very wealthy to shift investments away from property (Piketty, Citation2014) seems not to hold in Luxembourg.

The city of Dudelange (20,851 inhabitants in 2018), located on the French border in the South of the country, is the birthplace of Luxembourg’s modern steel industry. It covers just over 21 km2, of which approximately 7.5 km2 are currently built-up, with the remaining area split between woods and agricultural land. The majority of its residents (73.2%) owned their own home in the 2011 Population Census and property prices and rent levels are slightly below the national average. The population stagnated until the 1990s as the industrial based slowly withered away and the city has since gained over 6000 inhabitants. This recent growth is due to its close proximity to the capital city and its still relatively affordable property prices. This new population is mostly accommodated in new houses and apartments at the periphery of the existing urban fabric. The next section presents the data source used and provides a snapshot of the broad structure of property ownership in Dudelange.

The structure of property ownership in Dudelange

The analyses described in this article rely on information on property transfers drawn from notarial statements kept in the Luxembourg Land Registry’s archives.1 These notarial statements are automatically sent by notaries to the Land Registry to allow it to update its records on the ownership of land plots. These data provide information on the property goods themselves (type, size, location) as well as on their owner(s). In the cases in which a land plot or an apartment has more than one owner, the data distinguishes between four types of co-ownership: a married couple, a couple in a civil union,2 a group of heirs3 and voluntary co-ownership.4 This archival resource makes it possible to obtain a picture of the current day structure of ownership in Dudelange, as well to identify the mechanisms that have produced this structure.

In this study, the focus is on six types of property goods that are predominantly in private hands in Luxembourg: houses, apartments, residential land, other types of land, commercial buildings and other types of buildings (agricultural, industrial, etc.). This thus excludes transport, water and energy infrastructure, public buildings and green spaces, as well as forests (in large proportion nationally owned). The distinction between residential and other types of land is critical given the extreme difference in value between residential and other uses of land: for example, while a hectare of arable land in Luxembourg sold for an average of 35,590 euros in 2017 (Luxembourg Statistical Office), the average value of a hectare of residential land in the country between 2010 and 2017 was 6,874,200 euros (ODH, Citation2019a). In Dudelange, there are currently 57 hectares of residential land and 563 hectares of other land (agricultural, commercial and industrial), distinguished on the basis of the latest municipal zoning map. There are also 4534 houses, approximately 3700 apartments5 and 167 buildings that are neither residential nor administrative in purpose.

These properties are owned by 10,145 entities (counting all individuals and companies listed as owners) and 7231 entities if only the first listed owner is chosen (in the cases in which property is owned by more than person). This latter figure is a better representation of the number of unique owners, given that co-owners tend to be spouses or co-inheritors. To gain a more detailed picture of the structure of the ownership of property goods, estimates of property wealth shares have been computed. The figures are estimates because not all property transactions in the Land Registry archive feature a value for the property goods listed (such as in the case of inheritances). Two procedures have been used. The 2017 average price per m2 for the city of Dudelange drawn from Housing Observatory data was used to estimate the value of apartments. The value of residential land was estimated from the 2010 to 2014 average for the city as a whole, again drawing on Housing Observatory data. There is no precise information available on the value of land zoned as agricultural, commercial or industrial in Dudelange or in the south of the country. To estimate the value of non-residential land in private hands, I have decided to assign it a tenth of the value of residential land in Dudelange. This choice can be justified by the municipality’s modest size in a densely populated region (which means most of its land could one day be allocated to residential development). For houses and the other types of buildings, I have taken into account both the size of the building’s footprint6 and the amount of empty land in the remainder of the land plot (valued at half the price of residential land given the greater difficulty with which it can be mobilised for housing development). It is likely that these figures underestimate the actual concentration of property wealth as wealthier owners tend to own better quality property in more expensive areas. These estimates should not be directly compared to the wealth shares emerging from wealth surveys because they only measure the concentration of property among the owners listed for them (and thus not for the whole population of the area) and include both private persons and corporate actors. While imperfect, these estimates of the value of the six types of properties provide a first picture of the way in which the private ownership of a territory is structured.

Focusing on the first owners of the land plots concerned, the top 1% of property owners (that is the 72 individuals and companies in Dudelange with the most property wealth in the area) are estimated to own 17.9% of the property wealth in the area, the top 10% (723 entities) own roughly 36.5% and the top 20% (1446 entities in Dudelange) own roughly 48.6% of the municipality’s property wealth (see below). This high level of inequality, and especially at the very top, is driven by the high degree of concentration of residential land in Dudelange and across Luxembourg as a whole. Indeed, a distinction needs to be made between the levels of concentration in residential property and in residential land. In the European Central Bank’s Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), the top 1% of owners held 5% of the value of all Household Main Residences in the country. This contrasts with the results of a recent study that has shown that among the 15,907 private individuals who owned residential land in Luxembourg, the top 1% concentrated 25.1% of this land by value (ODH, Citation2019b). This degree of concentration is even higher among private companies: the 8 companies with the most valuable residential land holdings (the top 1%) concentrated 41.7% of the value of the residential land owned by companies (ODH, Citation2019b). This distinction between the level of concentration in residential property and in residential land is reflected in the estimates produced here for Dudelange (see above). The high level of inequality is driven primarily by the ownership of land plots (including here land as well as houses and the gardens that surround them), with the ownership of apartments showing a much smaller degree of concentration. The estimates computed for Dudelange are thus in line with those of the HFCS and the Housing Observatory.

Table 1. The structure of property ownership in current day Dudelange.

Top property owners and the production of the residential environment

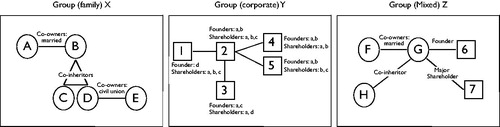

To move from the structure of the ownership of property to the way in which this structure affects the production of the residential environment, it is necessary to better grasp the number of unique decision makers operating in a given housing and land market. This means shifting from the individual level (individual or company) to the group level (family, conglomerate or a mix of the two) at which decisions related to property are taken. This is linked to the movement towards the re-familialisation of housing and welfare (Flynn & Schwartz, Citation2017; Ronald & Kadi, Citation2018), the fact that property developers in Luxembourg tend to create new companies for each of their projects and the fact that property can be owned both in one’s own name and through a company. As shown in below, groups are created by: 1. linking individuals based on the co-ownership of property goods in cases where this co-ownership stems from a marriage, a civil union or the receipt of an inheritance (Group X in ); 2. grouping companies together on the basis of the founders and major shareholders listed in their articles of association7 (Group Y in ); and 3. by mixing both individual and company links (Group Z in ).

Figure 1. An illustration of the three types of groups assembled for the analysis of top property owners.

Given the article’s focus on the influence of top property owners on the land and housing markets, I started at the top of the property wealth distribution and worked my way down until the property holdings of individual owners hit a threshold roughly equivalent to the ownership of 3 million Euros in estimated property wealth. When I encountered an individual, I searched all of the properties it owned in Dudelange for cases of co-ownership and picked up connected individuals from further down in the property wealth distribution to add to its group. In the case of companies, I extracted the founders and major shareholders and searched for them among the Dudelange property owners. Groups thus contain at least one individual or company at the very top of the property wealth distribution as well as other individuals and/or companies they are connected to located anywhere in the distribution.8 Following this method, 258 individuals and companies (3.6% of all first listed owners) were assembled into the top 105 groups representing 22.8% of all of the estimated property wealth in the area (8% of apartment-based wealth and 28.8% of house and land plot based wealth).9 The average property wealth of these 105 groups is 13 million Euros, ranging from 3 to 175 million Euros. The next section describes the three actors identified among these top property owning groups in Dudelange, followed by a detailed account of their respective roles in the production of the city’s residential environment.

Property developers, landowners and super-landlords

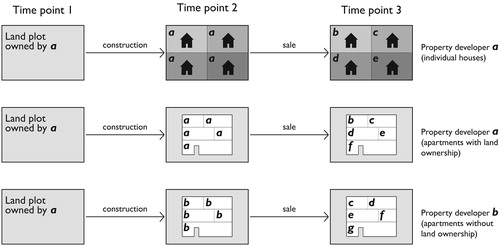

Based on the types of real estate property owned and the extent of their role in the production of housing, the 105 top property-owning groups in Dudelange were allocated to one of three categories. The most important criteria used to allocate a group to a category is whether the group can be considered to be a property developer. Property developers include all top property owners which are involved in the development of individual houses or apartment buildings. They can be identified through information on the former owners of land plots, houses and apartments. A property owner is categorised as a property developer if it is both the final owner of the land plot on which the new project stands and the first seller of the product developed. This is relatively straightforward for the development of individual houses given that there is only one trail of transactions to follow. An illustration of this is shown in the top row of above: group a can be identified as a property owner because it owned the land on which houses were built and is also the actor selling these houses. The situation is more complex for apartment buildings. In this latter case, the purchase of the land and the sale of completed apartments follow two distinct transaction trails. A group can be identified as a developer when it is listed as both the last owner of the land plot on which the building sits and as the first seller of the new building’s apartments (as shown in the second row of ). It is also identified as such when it was listed as the first owner of all of the apartments in a particular building10 (as shown in the last row of ).

If a group cannot be considered as a property developer, it is allocated either to the ‘landowner’ or to the ‘super-landlord’ category on the basis of the composition of its property wealth portfolio: for landowners, residential land and other types of land make up the majority of the estimated value of its property holdings; super-landlords, on the other hand, own mostly housing (houses within small land plots and apartments) and other types of buildings.

This classification of top property owners is a first, exploratory, attempt to draw on the detailed information available in the Luxembourg Land Registry to build a picture of property ownership that brings together both private persons and corporate actors. It focuses on two aspects of property ownership: 1. The degree of involvement of a property owner in the production of the residential environment and 2. The composition of the owner’s property portfolio, with a particular emphasis on the distinction between land and housing. This is a first proposition in the absence of detailed analyses of property ownership information drawn from the Land Registry in other contexts.

As shown in above, 26 of the 105 top property-owning groups in Dudelange have been found to be associated with property development. They account for just under a third of the property wealth in the hands of these groups but have the most valuable property portfolios. Dudelange’s recent resurgence linked to its relative proximity to the capital city and its still relatively affordable real estate has mostly been accompanied by the construction of individual houses on former agricultural land. This can explain why it has received limited attention from national-level property developers: while five of these were active in Dudelange, only three had a significant stake in local property wealth (over 10 million euros worth of property).

Table 2. The three types of groups at the top of Dudelange’s property wealth distribution.

Landowners are the most numerous among the 105 top property-owning groups in Dudelange and they account for 56.9% of the property wealth of these groups. There are three types of landowners among the 49 identified. First, companies that need land for their non-real-estate operations (4 groups – including the top property owner by value), second, investment funds in land (1 group) and third, private individuals or groups thereof (44 groups). The ownership of land in Dudelange is thus predominantly in the hands of private individuals and the origin of this land seems to be primarily from farming operations. Residential land prices have been increasing very rapidly in Luxembourg for the last decades (ODH, Citation2019a) and there is thus little incentive for landowners to sell their land in a context in which property taxes are extremely low and there is no inheritance tax for transfers between spouses or between parents and their children. This makes it very difficult for investment firms (and property developers) from outside of the area to acquire land.

The 30 super-landlords in Dudelange own just 10% of the estimated property wealth of the 105 top property-owning groups and the average value of their property portfolios is less than a third of that of property developers and landowners. It is informative to contrast the weight of these super-landlords to that of the small-scale landlords operating in the case study area. Small-scale landlords are those who own more than one apartment or house but who have less than 3 million euros in estimated property wealth. There are 628 of these small-scale landlords in Dudelange and they account for 14.7% of the total estimated property wealth in the area – as compared to 2.3% for the 30 super-landlords. On average, super-landlords have three times the property wealth of small scale landlords. The majority of the estimated property wealth held by landlords is thus in the hands of individuals with relatively few housing goods. This mirrors the trend of rising small scale landlordism in the UK context (Ronald & Kadi, Citation2018), but is also a reflection of the fact that the most important actors at the top of property wealth distribution, rather than landlords, are those which are able to mobilise capital, land or both to control the type and location of housing developed. This process is the focus of the next section.

Planning and land assembly: top property owners and the production of the residential environment in Dudelange

The aim of this section is to move beyond the static picture of top property wealth and to present some of the mechanisms through which the structure of the ownership of property wealth affects the production of the residential environment. It draws on an analysis of the process through which planning permission was obtained and land was assembled in the six largest property development schemes in Dudelange since the end of the 1970s. Given the size of these developments (between 4 and 16 hectares), they required planning permission to be developed even though the land they mobilised had already been zoned as residential. The planning applications for these developments were obtained from the archives of the Interior Ministry in Luxembourg. These planning applications were studied alongside the Land Registry archives that show the process through which the land required for these schemes was assembled. This analysis reveals at the same time a degree of diversity in the processes through which these developments emerged from the ground and a striking overlap in the actors (both property developers and landowners) involved.

There are three main configurations through which planning and land assembly for large-scale residential developments was secured. The most common (found in five of the six developments) takes the form of a planning request by a large landowner for the land it owns. This entails receiving permission to slice up land into small land plots that can then be sold at a premium to developers. All five of the landowners who adopted this strategy can be linked to groups at the top of the property wealth hierarchy (groups number 2, 3, 47, 53 and 62 by total estimated property wealth). Group number 3 sold land in this way in two separate developments. The fact that these landowners are among the top property owners in Dudelange today after having sold off large tracts of land provides some indication that they are releasing land holdings progressively as part of a property wealth accumulation strategy that is deployed across multiple generations. It is also striking that landowners have been so active in drawing on the planning apparatus to maximise the value of the land they do decide to sell off.

The second configuration corresponds to the four cases in which property developers have led both the land assembly and planning permission processes. Three property developers have been involved here. Two areas were assembled and planned by a local property developer (group number 85 in the property wealth hierarchy), purchasing once from group number 2 in the property wealth hierarchy and once from group 53. The other two areas were assembled and planned by national-level property developers. Both are still active and have significant operations in Dudelange (groups number 4 and 23 in the property wealth hierarchy). Group 23 purchased land from a landowner not among the top 105 groups, while group 4 acquired the land from groups number 30, 47 and two other landowners not among the top 105 groups at the top of the property wealth hierarchy.

The third configuration was identified in two areas only and gives insights into the relations between property developers and landowners in the production of the residential environment. In one case, a local property developer (group number 51 in the property wealth hierarchy) applied for an alteration of the planning permission granted to the landowner he then purchased land from. This was beneficial to the landowner (group 62) because the land was only purchased after the planning permission had been modified. In the other case, 16 landowners sold land to a single local property developer who then applied for planning permission, cut up the total land area in building plots and sold back a portion of these plots to each of the 16 landowners for exactly the same amount he had bought the original land from them for. This was clearly an operation that was coordinated to profit both the property developer and each landowner: through the operation, the property developer (group 85 in the property wealth distribution) secured building plots for itself at the cost of the planning application only; the landowners received less land back than what they had originally sold, but this land was now in the form of building plots that could be sold on at higher value or developed. Among the 16 landowners involved in this deal, 10 are amongst the top 105 property owners in Dudelange (groups: 2, 8, 10, 11, 12, 38, 39, 51, 53 and 85 – the developer also owned land in the area).

These three configurations are a first attempt at capturing the ways in which the groups at the top of the property wealth hierarchy extract value from the production of the residential environment homeowners and landlords of all sizes consume. Looking at the production of the residential environment in this way reveals how few actors are involved. Group 2 is for example found in all three configurations: it requested planning permission before selling off its land, sold land to a developer who had gained planning permission and was one of the 16 landowners who agreed to a mutually beneficial deal with a property developer. There are however more links to be drawn here as the developer group 2 sold land to in the second configuration (group 85) is also the developer that led the mutually beneficial deal. Another landowner (group 53) – also found in all three configurations – is in a similar position vis-à-vis group 85: it sold land to group 85 and was involved in group 85’s deal with landowners. A crude way to summarise these links is to say that among the 16 groups at the top of the property wealth hierarchy involved in these 6 large-scale housing developments, two were found to be active in all three configurations (2 and 53), four were found to be active in two (47, 51, 62 and 85), with the other 10 only active in one of the three configurations. This exploratory analysis thus reveals not only that a small number of actors at the top of the property wealth hierarchy have an overwhelming influence on the production of housing, but also that there are multiple links to be drawn between these actors across large scale developments launched at different times and in different areas of the city. This analysis also provides a glimpse of the shifting boundaries between landowner and property developer: many of the large landowners involved in these schemes have since taken on property development projects (such as groups 2, 3 and 11). Thus, while property developers and landowners are estimated to own just over a fifth of property wealth in Dudelange, these 75 groups at the top of the property wealth distribution are in a privileged position to control the production of the residential environment.

Conclusion

This article is an exploratory investigation of the influence on the housing and land markets of the property owners at the top of the private property wealth distribution in Dudelange, drawing on archival material from the Land Registry. The property wealth estimates developed in this study aim to capture the orders of magnitude involved and make possible two contributions to the study of property wealth.

First, it studies top property ownership at the ‘group’ scale, be it the family, the corporate group or a blend thereof. The family unit of analysis brings into light the intergenerational transmission of property wealth as the wealth accumulated through property development or the mobilisation of land provides an advantage to the next generation, regardless of its involvement in these processes. This can be seen in the fact that a number of top property holdings have been constituted through the strategic management of land reserves across generations. Moving from the level of the individual company to that of the corporate group provides a means to piece together activities and schemes which seemed separate and to gain a better understanding of the influence of these real estate interests on the housing market.

Second, this study is a first proposition of a method to classify top property owners according to their degree of involvement in the production of the residential environment and the composition of their property wealth portfolios. While comparative work is needed to test the generalisability of the property wealth shares found in Dudelange for property developers, landowners and super-landlords, it seems likely that these three types of actors will also be found in other types of areas. These shares might fluctuate according to the degree of openness of the area to global capital flows into real estate – the Dudelange case, with the strong grip exercised by local landowners on residential land clearly represents only one possible configuration.

In summary, the analysis revealed the central importance of a small set of tightly interconnected landowners and property developers in the Dudelange land and housing markets. This result justifies the focus on the role of private actors at the top of property wealth distribution rather than on the changing distribution of housing within the ‘wealth middle classes’ or the changing housing consumption behaviours of the super-rich: in Dudelange, landlords of all sizes have little say over the production of the residential environment. In complement to the work on the financialisation of property development, the results also show that the property developers involved in the largest schemes are mostly drawn from Dudelange itself and have in many cases originated from within the ranks of its large landowners. The exploratory analyses also reveal the relatively limited role of public actors in the production of housing: in the six schemes analysed, public authorities were insignificant landowners, constraining their ability to shape what is produced in a context of a chronic under-supply of housing.

The case of Dudelange thus highlights the importance of private landowners in a country with low taxes and rapidly increasing land and house prices. In such a context, releasing land for development appears to be a complex process that relies on social connections and which makes entrance difficult for investors and firms from outside the area. Local landowners at the top of the property wealth hierarchy – who are nearly all groups of private individuals – still own just under 400 million euros worth of residential land in Dudelange, 376 million of which are in the hands of groups among the top 105 by property wealth. These groups will likely continue to exercise a significant degree of control over residential development in the foreseeable future. This makes it crucial to study in more depth the ways in which multiple property ownership is interlinked with access to land. The Dudelange case shows that a high degree of concentration of property wealth is not innocuous: it puts a small group of actors in a privileged position to manage the production of housing as a means to further family-level property wealth accumulation.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the special issue editors Justin Kadi, Christian Lennartz, Cody Hochstenbach, my colleagues Antoine Decoville, Markus Hesse, Brano Glumac, Javier Oliveira and Julien Licheron as well as the three anonymous reviewers for their critical and constructive comments. I would also like to thank the Administration du Cadastre et de la Topographie for all of their kind help since the beginning of this project. I am also indebted to the research assistants who have been essential to the creation of the Dudelange property transactions database: Olivier Bichel, Tiago Ferreira Flores, Kidane Tesfamariam, François Blom-Peters, Bianca Da Silva Barreto, Charles Desforges, Lounece Makhloufi, Bruno Salmon, Corentin Cézard, Maxime Barbier, Célia Legrand, Gaby Dragut, Gaëlle Clicque, Sophie Pit, Gildo Pinto Fonseca, Jérome Conzemius, Paul Boissot, Tatiana Ferreira Flores and Kélya Hamdi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Land Registry freely delivers information on the ownership of land plots to members of the public through its online platform Geoportail. The information analysed here is the trail of transactions that led to the current day structure of property ownership.

2 Introduced by the law of 9 July 2004, a civil union (PACS) provides legal security in civil, fiscal and social security matters for two people, of the same or different gender, who have decided to live together without getting married.

3 This occurs when a property is passed through an inheritance to more than one person.

4 These are properties for which a number of owners have agreed to share the ownership.

5 There is uncertainty as to the exact number of apartments because not all buildings have a detailed ‘vertical land registry’ which identifies the nature of each good.

6 This is the only information available on the size of the house. For Dudelange as a whole, this building footprint represents a quarter of the land plot on average.

7 These articles of association are only available for domestic companies. In cases in which a foreign company is involved in property development in Luxembourg, a local subsidiary is usually created.

8 Groups can contain different numbers of individuals and/or companies but are considered as one owning entity: decisions about what to do with the property are likely made in concertation within a particular group.

9 The top 1% of these groups (71 groups) concentrated 20.6% of Dudelange’s estimated property wealth, as compared to 17.9% for top 1% of individuals.

10 This would mean that the property developer does not own the land on which the apartment building is built.

References

- Adisson, F., & Artioli, F. (2019). Four types of urban austerity: Public land privatisations in French and Italian cities. Urban Studies, 004209801982751. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0042098019827517

- Arundel, R. (2017). Equity inequity: Housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the Rise of Private Landlordism. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(2), 176–200. doi:10.1080/14036096.2017.1284154

- Atkinson, R., Burrows, R., & Rhodes, D. (2016). Capital city? London’s housing markets and the ‘super-rich. In I. Hay and J. V. Beaverstock (Eds.) Handbook on wealth and the super-rich (pp. 225–243). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Badcock, B. (1994). Snakes or ladders?’ The housing market and wealth distribution in Australia. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 18(4), 609–627. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.1994.tb00289.x

- BCL. (2015). Revue de stabilité financière. Luxembourg: Banque Centrale du Luxembourg.

- Beaverstock, J. V., Hubbard, P., & Short, J. R. (2004). Getting away with it? Exposing the geographies of the super-rich. Geoforum, 35(4), 401–407. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2004.03.001

- Benton, R. A., Keister, L. A., & Lee, H. Y. (2017). Real estate holdings among the super-rich in the USA. In R. Forrest, S. Yee Koh, & B. Wissink (Eds.), Cities and the super-rich (pp. 41–62). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burbidge, A. (2000). Capital gains, homeownership and economic inequality. Housing Studies, 15(2), 259–280. doi:10.1080/02673030082388

- Christophers, B. (2016). For real: Land as capital and commodity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(2), 134–148. doi:10.1111/tran.12111

- Christophers, B. (2019). Putting financialisation in its financial context: Transformations in local government‐led urban development in post‐financial crisis England. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(3), 571–586. doi:10.1111/tran.12305

- Coulter, R. (2017). Local house prices, parental background and young adults’ homeownership in England and Wales. Urban Studies, 54(14), 3360–3379. doi:10.1177/0042098016668121

- Cowell, F. A., Nolan, B., Olivera, J., & Van Kerm, P. (2017). Wealth, top incomes and inequality. In K. Hamilton & C. Hepburn (Eds.), National wealth: What is missing, why it matters (pp. 175–204). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fernandez, R., Hofman, A., & Aalbers, M. B. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(12), 2443–2461. doi:10.1177/0308518X16659479

- Flynn, L. B., & Schwartz, H. M. (2017). No exit: Social reproduction in an era of rising income inequality. Politics & Society, 45(4), 471–503. doi:10.1177/0032329217732314

- Forrest, R., & Murie, A. (1989). Differential accumulation: Wealth, inheritance and housing policy reconsidered. Policy & Politics, 17(1), 25–40. doi:10.1332/030557389783219460

- Guironnet, A., Attuyer, K., & Halbert, L. (2016). Building cities on financial assets: The financialisation of property markets and its implications for city governments in the Paris city-region. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1442–1464. doi:10.1177/0042098015576474

- Hamnett, C. (1991). A nation of inheritors? Housing inheritance, wealth and inequality in Britain. Journal of Social Policy, 20(4), 509–536. doi:10.1017/S0047279400019784

- Hamnett, C. (1992). The geography of housing wealth and inheritance in Britain. The Geographical Journal, 158(3), 307–321. doi:10.2307/3060300

- Hamnett, C. (1999). Winners and losers: Homeownership in Modern Britain, London: UCL Press.

- Hay, I., & Muller, S. (2012). That tiny, stratospheric apex that owns most of the world’–exploring geographies of the super‐rich. Geographical Research, 50(1), 75–88. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2011.00739.x

- Hochstenbach, C. (2018). Spatializing the intergenerational transmission of inequalities: Parental wealth, residential segregation, and urban inequality. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(3), 689–708. doi:10.1177/0308518X17749831

- Hyötyläinen, M., & Haila, A. (2018). Entrepreneurial public real estate policy: The case of Eiranranta, Helsinki. Geoforum, 89, 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.04.001

- Kim, S. (2003). Long-term appreciation of owner-occupied single-family house prices in Milwaukee neighborhoods. Urban Geography, 24(3), 212–231. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.24.3.212

- Murie, A. (1991). Divisions of homeownership: Housing tenure and social change. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 23(3), 349–370. doi:10.1068/a230349

- ODH. (2016). Le logement en chiffres au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Number 5. Available from http://observatoire.liser.lu/pdfs/Logement_chiffres_2016T2.pdf

- ODH. (2019a). Les prix de vente des terrains à bâtir en zone à vocation résidentielle entre 2010 et 2017. Note Number 24. Available from https://www.liser.lu/publi_viewer.cfm?tmp=4314

- ODH. (2019b). Le degré de concentration de la détention du potentiel foncier destiné à l’habitat en 2016. Note Number 24. Available from https://www.liser.lu/publi_viewer.cfm?tmp=4313

- ODS. (2013). La cohésion territoriale au Luxembourg: Quels enjeux? Observatoire du Développement Spatial, Luxembourg: CEPS/INSTEAD.

- Osier, G. (2011). Regards sur le patrimoine des ménages. Regards. Luxembourg: STATEC.

- Paccoud, A. (2017). Buy-to-let gentrification: Extending social change through tenure shifts. Environment and Planning A, 49(4), 839–856. doi:10.1177/0308518X16679406

- Paris, C. (2017). The super-rich and transnational housing markets: Asians buying Australian housing. In R. Forrest, S. Yee Koh, & B. Wissink (Eds.), Cities and the super-rich (63–83). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2014). Inequality in the long run. Science (New York, N.Y.), 344(6186), 838–843. doi:10.1126/science.1251936

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. (A. Goldhammer, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- Pollard, J. (2009). Political framing in National Housing Systems: Lessons from real estate developers in France and Spain. In H. M. Schwartz & L. Seabrooke (Eds.), The politics of housing booms and busts (pp. 170–187). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Romainville, A. (2017). The financialization of housing production in Brussels. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(4), 623–641. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12517

- Ronald, R., & Kadi, J. (2018). The revival of private landlords in Britain’s post-homeownership society. New Political Economy, 23(6), 786–803. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1401055

- Sanfelici, D., & Halbert, L. (2016). Financial markets, developers and the geographies of housing in Brazil: A supply-side account. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1465–1485. doi:10.1177/0042098015590981

- Thomas, B., & Dorling, D. (2004). Know your place: Housing, wealth and inequality in Great Britain 1980–2003 and beyond. London: Shelter.

- Thorns, D. C. (1989). The impact of homeownership and capital gains upon class and consumption sectors. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 7(3), 293–312. doi:10.1068/d070293

- van Loon, J. (2016). Patient versus impatient capital: The (non-) financialization of real estate developers in the low countries. Socio-Economic Review, 14(4), 709–728. doi:10.1093/ser/mww021

- van Loon, J., & Aalbers, M. B. (2017). How real estate became ‘just another asset class’: The financialization of the investment strategies of Dutch institutional investors. European Planning Studies, 25(2), 221–240. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1277693

- Walks, A. (2016). Homeownership, asset-based welfare and the neighbourhood segregation of wealth. Housing Studies, 31(7), 755–784. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1132685

- Wind, B., & Hedman, L. (2018). The uneven distribution of capital gains in times of socio-spatial inequality: Evidence from Swedish housing pathways between 1995 and 2010. Urban Studies, 55(12), 2721–2742. doi:10.1177/0042098017730520

- Wind, B., Lersch, P., & Dewilde, C. (2017). The distribution of housing wealth in 16 European countries: Accounting for institutional differences. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(4), 625–647. doi:10.1007/s10901-016-9540-3

- Ziegelmeyer, M. (2015). Other real estate property in selected euro area countries. Working Paper Series No 99. Banque Centrale du Luxembourg, Luxembourg.