Abstract

Although the role of the housing sector in the unfolding of the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis has been studied extensively, the post-crisis nexus between housing and finance has not received equal attention. Grounded in a comparative case study between Canada and the Netherlands, this article adds situated knowledge from mortgage market professionals. It discusses the state interventions for regulating mortgage markets that were pursued by each national government during and after the crisis. Our analysis shows that in both cases state interventions contributed to restoring the investment value of mortgage products and failed to de-link housing from global speculative financial practices. Standardised lending regulations targeting the ‘average man’ were put in place. These contributed to further excluding non-prime households from mortgage markets, and drove them into risky practices, such as borrowing outside regulated markets. In addition, the new regulatory regimes forced households that retained access to mortgage markets to become highly leveraged and exposed to increased risks in future crises scenarios. We argue that the policies put in place as a response to the crisis in Canada and the Netherlands, ultimately led to a shift in risk-taking from lenders to current and prospective mortgage holders.

Introduction

In response to the profound impact that the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis (henceforth GFC) had on housing and mortgage markets, many countries revised and strengthened their mortgage lending regulations and practices. Some of the typical measures that countries adopted during this period included lowering loan-to-value ratios, decreasing amortisation periods and putting in place stricter income requirements for access to household mortgages (IMF, Citation2011). Over the past decade, a significant body of literature examined the changes in regulations and the increasingly complex nexus between housing and finance. This literature offered important insights on how the post-crisis reforms targeted primarily the quality of the commodity within a market in distress, (i.e., mortgage products), rather than the mortgage market itself (Ashton & Christophers, Citation2018). This body of literature also documented how in the aftermath of GFC, mortgage lenders turned to low-risk investment opportunities favouring financial primes coming from private wealth, from households with high income and a stable employment status. The result was the decrease in access to mortgaged housing for younger generations and for low- and middle-income households (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; Hochstenbach, Citation2017; Jonkman & Janssen-Jansen, Citation2015; Lennartz et al., Citation2016; Yates, Citation2014). As many authors have documented, post-crisis state actions have reinforced the relationship between finance and urban space, contributing to increasingly unaffordable housing markets (Beswick et al., Citation2016; Murphy, Citation2011).

In this paper, we seek to expand the understanding of post-crisis mortgage landscapes through a comparative case study of the Netherlands and Canada. These countries lend themselves to an interesting comparative analysis for a number of reasons. First, the household debt to disposable income ratio in both countries ranks amongst the highest in the world (276% in the Netherlands, and 173% in Canada (OECD, Citation2018)). Second, housing mortgage markets in the Netherlands and Canada are highly securitised and deeply intertwined with state policies and subsidies (Aalbers et al., Citation2011; Engelen & Glasmacher, Citation2018; Walks, Citation2014). Third, in both cases, national governments used mortgage debt as an instrument to save financial institutions, and restore national housing and economic markets (Boelhouwer, Citation2017; Carter, Citation2012; Scanlon & Elsinga, Citation2014; Walks, Citation2014). Our comparative evaluation of the similarities between the two countries contributes to a better understanding of the role of the state in the evolution of advanced mortgage markets.

Our study adds situated knowledge from mortgage market professionals, which is a relatively rare area of focus for qualitative empirical studies on post-crisis mortgage markets. Our methods include a review of mortgage related policy changes between 2007 and 2018 in both countries, an analysis of quantitative data sources from the World Bank and national housing statistics (CMHC in Canada and CBS in the Netherlands) and 29 semi-structured interviews with mortgage lenders, mortgage brokers and government officials. The data collection and analysis was carried out between September 2018 and January 2019.

In the sections that follow, we first situate our study within the body of literature that examines the relationship between housing and finance. Then, we present the changes in mortgage regulations that took place between 2007 and 2018 in Canada and the Netherlands, and discuss their implications for (prospective) mortgage holders and investors. Finally, we synthesise key findings and demonstrate how policy changes in both cases contributed to lower-risk investment opportunities that secured the investment value of housing and related debt products. Rather than dismantling the financialised housing system, this resulted in further increasing housing prices and in shifting risk-taking from investors to mortgage holders.

Housing unaffordability, debt and finance

According to Wetzstein (Citation2017) a ‘Global Urban Housing Affordability Crisis’ is currently unfolding. Cities like Vancouver, Toronto (Andrle & Plašil, Citation2019), Amsterdam (Lennartz et al., Citation2019), Sydney (Birrell & McCloskey, Citation2016), and Hong Kong (Huang, Citation2015) are struggling with severe affordability issues. The social and economic consequences of increased housing unaffordability are variegated and far reaching, ranging from a sharp increase in mental health problems, to the impediment of job prospects, the destruction of family relations (Roberts, Citation2016; Turffrey, Citation2010), and the accentuation of social inequalities between those who own property and those who do not (Piketty, Citation2015; Ronald et al., Citation2017).

Many authors have directly linked the decrease in housing affordability to an increase in mortgage credit availability (Barone et al., Citation2020; Justiniano et al., Citation2019; McLeay et al., Citation2014; Ryan-Collins et al., Citation2017; Tsatsaronis & Zhu, Citation2004). In the twentieth century, household mortgage lending became one of the core activities of the banking sector (Bezemer et al., Citation2016). This has led to an excessive growth of household debt to GDP ratios over the last century (Jordà et al., Citation2016). Correlations between the increased availability of mortgage credit and the rising of housing prices have been documented in Canada (Walks, Citation2014), and the Netherlands (DNB, Citation2020), amongst many other advanced and emerging economies (IMF, Citation2011).

The growth of debt on the balance sheets of financial institutions and households has been accelerated by the financialisation of housing (Aalbers, Citation2008). Financialisation refers to the process by which profit is increasingly made without actual production; i.e., by solely trading financial and immaterial assets (Aalbers, Citation2008; Engelen, Citation2008; Epstein, Citation2005; Krippner, Citation2005). Mortgage loans and the homes and households backing them have been subject to this new regime of financialised accumulation (García‐Lamarca & Kaika, Citation2016; Rolnik, Citation2019). This means that mortgage markets have shifted from being an auxiliary to the housing market, towards becoming a market of mortgage products in its own right. Through deregulation, standardisation and the internationalisation of finance, mortgage products have become highly valued investment goods, yielding profits on global capital markets (Aalbers, Citation2008). As securities (packaged mortgage portfolios) and covered bonds, mortgages are now a source of liquidity that financial institutions use to ‘recycle debt’ and fund new loans, providing more input for the house price-debt feedback cycle (e.g., an increase in prices requires an increase in mortgage credit, which in turn, further inflates home prices).

At a more abstract level, the process of financialisation has facilitated the switching of capital from the primary circuit (production and manufacturing) towards the secondary circuit (the built environment and consumption) (Aalbers, Citation2008). Drawing on Marx’s notions of capital circuits, Harvey (Citation2006) describes how capital switching from one circuit to another is used as a temporary solution to over-accumulation-postponing financial crises caused by the devaluation of capital. Investment in property is, therefore, according to Harvey, foremost a strategy to secure a rate of return on capital that would otherwise become devalued. Capital switching therefore links global cycles of capital overaccumulation and disinvestment to changes in the built environment. This process contributes to transforming mortgage contracts into opaque impersonal products (Kaika, Citation2017), and housing into an investment opportunity, making mortgage holding households part of a system “that seeks out surplus value in order to produce more surplus value, that then requires profitable absorption (…) with disastrous social, political and environmental consequences” (Harvey Citation2006: xxvi). Housing and debt related products have thus not only been an object of financialisation over the past decades, but also a fundamental aspect of contemporary accumulation. As such, Fernandez and Aalbers (Citation2016) speak of ‘housing-centred financialisation’ processes, pointing to the pivotal role of housing in the current ‘debt-led accumulation regime’.

The two cases in this study are prime examples of this process of financialisation of housing. In Canada the national government started to promote the expansion of the mortgage market from 1980 onwards. Key was the establishment of two public securitisation programmes both run by the crown corporation ‘Canada Mortgage and Securitization Corporation’ (henceforth CMHC). Walks and Clifford (Citation2015) argue that CMHC played a crucial role in the financialisation of housing before the GFC. Through reducing lending standards and subsidising securitisation, it stimulated the growth of shadow banking, interest-only, and subprime mortgage contracts that resulted in the increase of household debt. Between 1970 and 2007 mortgage debt to GDP ratios increased from 17.5 to 45.6 (based on data from StatCan (Citation2019) and World Bank (Citation2019)). In the Netherlands, financialisation of housing was actively promoted by the national government and banking sector from 1990 onwards. Whilst the social housing sector suffered several cuts and deregulations (Kadi & Musterd, Citation2015; Van Gent, Citation2013), favourable public-led guarantee and tax-break schemes lowered the cost of lending for households and promoted competition in the mortgage market. Banks started to expand their credit limits (Aalbers et al., Citation2011; Boelhouwer & Schiffer, Citation2015) and became more lenient in issuing mortgages (Aalbers et al., Citation2011; Kakes et al., Citation2017). New products such as interest-only mortgages were introduced, making mortgages an increasingly risky undertaking for low- and middle- income households. Particularly since a large share of interest-only mortgage holders are unaware of the fact that they are actually not repaying capital on their mortgage debt with their monthly repayments (DNB & AFM, Citation2009). In 1993, interest-only repayment mortgages made for 3.4 percent of all new mortgages in the Netherlands, while in 2006 this number had risen to 44 percent (Scanlon et al., Citation2008). The share of mortgage debt on the balance sheets of Dutch banks rose from 12 percent in the early 90 s to more than 20 percent just before the crisis; and this figure did not even include the mortgages removed from the banks’ balance sheets with securitisation techniques (Kakes et al., Citation2017). As a consequence, residential mortgage debt as a share of GDP grew from 54 percent in 1995 to 96 percent in 2007 (Based on data from CBS, Citation2005, Citation2014, Citation2019).

Canada and The Netherlands during the global financial crisis

When the crisis started to unfold in 2007 both the Canadian and the Dutch Banking sectors were faced with liquidity issues and declining bank valuations (Arjani & Paulin, Citation2013; DNB, Citation2010; Scanlon & Elsinga, Citation2014). In the years that followed, regulating mortgage debt played an instrumental role in restoring the national housing markets and the national economies as a whole. In Canada, the federal government authorised a loan to the Canadian Mortgage and Securitization Corporation (CMHC) in order to assist the crown corporation to purchase mortgage-backed securities from failing financial institutions. This was an operation of a total of 137.55 billion Canadian dollars between the fall of 2008 and the end of 2009 (Walks, Citation2014). On top of direct liquidity injections, the Canadian government further expanded the public securitisation Canada Mortgage Bond programme (henceforth ‘CMB’) in order to make bonds more attractive to a wider pool of investors (Carter, Citation2012; CMHC, Citation2018).

In the Netherlands, by contrast, the state guaranteed the portfolio of only one financial institution consisting of failing American residential mortgage backed securities. The insurance scheme covered a total of 21.5Footnote1 billion euros, and ended in 2014 (Government of the Netherlands, Citationn.d.; The Court of Audits, Citation2018; The Court of Audits, Citation2019). In addition, the Dutch government increased the limit of mortgage guarantee from 265.000 to 350.000 euros and reduced the property transfer tax from 6 to 2 percent, in order to lower real estate transaction costs. This last measure was meant to be temporary, however, in 2012 the government decided to make it permanent (Scanlon & Elsinga, Citation2014).

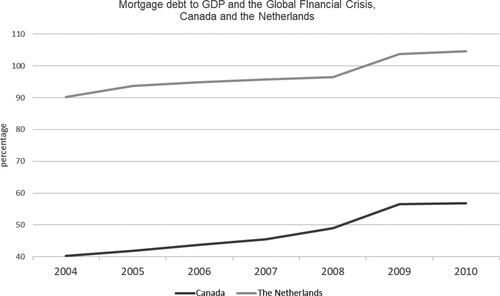

Aside from measures that specifically targeted the mortgage and housing market, both countries issued measures to reduce the cost of capital in general. The Central Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank reduced their official interest ratesFootnote2 a number of times between 2007 and 2018. Direct liquidity was also injected through loans and capital support for the financial sector. These measures persisted after the GFC, as official interest rates continued to be lowered and an additional ECB purchase programme was introduced in 2015 (ECB, Citation2019). The anti-crisis measures in both Canada and the Netherlands encouraged sustaining mortgage lending and keeping the debt-economy flowing, and created more fictitious capital and effective demand. shows that mortgage debt levels were already growing in the pre-crisis years, but spiked between 2007 and 2010, though levels in the Netherlands were already much higher due to pre-crisis increases.

Figure 1. Mortgage debt Canada and the Netherlands 2004–2010.

This figure shows the collective outstanding residential mortgage debt as a share of the Gross Domestic Product in Canada and the Netherlands between 2004 and 2010. Source: CBS (Citation2005, Citation2014, Citation2019), StatCan (Citation2019) and the World Bank (Citation2019).

Post-crisis: changes in mortgage regulations

The GFC marked a significant shift in mortgage lending policies. Legislative changes in both Canada and the Netherlands tightened and standardised lending conditions in order to restore mortgage markets and sustain capital flows in the financial sector. In both countries, the measures had similar targets: to enhance financial stability by increasing the quality of lending, and to decrease household debt levels. However, the methods used in each country varied.

From 2008 onwards, the Federal Government of Canada started to implement a series of new mortgage regulations (listed in ): a required down payment of five percent (2008); the establishment of a minimum required credit score to apply for a mortgage loan (2008); the decrease of the maximum amortisation term from 40 to 25 years (2012); and most recently a ‘stress test’ (2018) to ensure that households would still be able to pay their mortgage in the case of a two percent increase in interest rates. Respondent CA-A, a government official working for the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), explains:

Table 1. Timeline of mortgage rule changes in Canada.

‘In Canada [debt levels] have been going up quite quickly (…) it would almost take them [households] two years to pay down the debt if they spent money on nothing else. So, there is a big risk to the economy (…) so the idea is, if we can curve the increase in credit, that makes for less chance of a recession’ (Respondent CA-A, government employee working for CMHC, November 2018)

On top of tightening lending conditions, the Canadian government temporarily ceased the expansion of public securitisation programmes. According to the Economic Action Plan of the Government of Canada (Citation2014) the key objective of this policy turn was to “increase market discipline in mortgage lending” and “reduce taxpayer exposure to the housing sector”. Calculations based on CMHC (Citation2018) data on the total outstanding balance of public securitisation programmes, show that in 2017 the total volume of the securitisation programmes was still 484 billion dollars. This means that a great deal of mortgage loans continued to be traded on capital markets, and the Canadian taxpayer was exposed for a sum almost triple that of the total amount of mortgages before the financial crisis (166 billion in 2007). However, because of the development of a new mortgage landscape after the financial crisis, the quality of the underlying mortgage contracts increased, thus decreasing the chances of defaults. Arguably, the primary goal of the stricter mortgage regulations was restoring financial stability, rather than de-financialising the housing sector. As respondent CA-A explains:

‘(…) a lot of the policy stuff was mostly driven by concerns on the financial stability side, I don't know if there was any sort of a compensating… like “if we are making it more difficult for people to buy their homes, are we giving them viable alternatives?”’ (Respondent CA-A, government employee working for CMHC, November 2018)

In the case of the Netherlands, by contrast, the first reforms were not put in place by state action; they originated within the banking sector itself. The Association of Dutch Banks introduced a new Code of Conduct for Mortgage Loans (GHF) in 2011. The code was advisory, but not legally binding, and announced stricter criteria for maximum loans and housing costs. In 2013, however, the national government translated (most of) the code into a legally binding regulation, the ‘Tijdelijke Regeling Hypotecair Krediet’ [Temporary mortgage credit regulation]. In addition, the new regulation included a gradual reduction of the maximum permitted loan-to-value ratios, which reached 100 percent in 2018. From that year onwards, households were no longer allowed to borrow more than the market value of their house (Ministry of Finances, Citation2012b). This meant that they needed to use private resources to cover the transaction costs of a mortgage (e.g., the transfer tax and notary costs, which usually amount to 2 to 2.5 percent of the house price).

In 2013, the Dutch national government took the regulations further and curtailed the mortgage interest tax deductibility for interest-only mortgage products; this gave the final blow to interest-only mortgage products, as only annuity and linear mortgages could claim tax benefits for interest repayments. Households that obtained an interest-only type of mortgage before 2013 were still allowed to deduct this from taxes, and could take their existing contract type with them when moving and closing a new mortgage deal (Ministry of Finances, Citation2012a). Moreover, the Dutch Authority for Financial Markets (AFM) urged the Dutch Associations of Banks in 2016 to promote the repayment of interest-only mortgages. The Dutch Association of Banks launched a ‘aflossingsblij’ (repay-happy) campaign, stimulating clients with (partly) interest-only mortgages to gain insight into their financial situation. Respondent NL-A, employee of the Association of Dutch Banks, explains why this campaign was set up:

‘suddenly, [the large bulk of interest-only mortgages] was seen as a problem by the AFM. The Central Dutch Bank and AFM were afraid that when households with an interest-only mortgage have to refinance at the end of the term, they would run into problems (…) It is hard to say what the problems will be, but we understand the concern, so we make people conscious of the risks of not repaying their mortgage debt. Now we try to make people ‘repay-happy’. That does not necessarily mean that they have to repay their debt, but primarily that people have more insight into their situation.’ (Respondent NL-A, employee of the Association of Dutch Banks, March 2019)

Besides discontinuing the tax deductibility of interest-only mortgage products, the national government also agreed to reduce the maximum rate of mortgage interest deductibility for all new mortgages down to a maximum tax advantage of 37.05 percent in 2023 (Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Citationn.d.). presents an overview of the series of adjustments made since the financial crisis by the national government.

Table 2. Timeline of mortgage rule changes in the Netherlands.

Although most regulations put in place in the Netherlands over the last decade curtail mortgage lending, there are also some legislative changes that take mortgage lending in the opposite direction. Between 2013 and 2018, the maximum permissible mortgage loan for double-income households increased, and from 2018 onwards loan-to-value ratios of 106 were allowed in cases where energy saving renovations were stipulated. In 2017, regulations for tax-free gifts (e.g., from parents to children) for home purchases were also expanded.

Similar to the Netherlands, in Canada too, local programmes were set up to stimulate mortgage lending, while at the same time tightening mortgage regulations. The first-time home buyers assistance programme in the province of British Columbia in 2016 contributed to the required down payment of 5 percent in the form of a second mortgage, which is interest-free and payment-free for the first 5 years. These measures lowered the costs of purchasing real estate for households that are able to successfully apply for a mortgage and/or have the social resources to receive a tax-free wealth transfer.

Implications for (prospective) mortgage holders in The Netherlands and Canada

The previous section outlined the new mortgage landscapes that emerged in Canada and the Netherlands after the crisis, noting how these were characterised by tightened lending conditions and standardising risk-averse approaches. summarises the most important changes in both cases. The mortgage brokers we interviewed in both countries recognised this. Respondent CA-K, mortgage specialist at a popular lending institute in Vancouver, comments upon the rigidity of the regulations after the crisis:

Table 3. Comparison mortgage rule changes.

‘The rules are kind of the rules. There is not a lot of wiggle room.’ (Respondent CA-K, mortgage specialist at lending institute in Canada, October 2018)

Respondent NL-G, who has been a mortgage broker for over twenty years, sees a similar development in the Netherlands:

‘You can see that the mortgage process becomes standardised. Compliance [to regulations] and risk aversion now rule the lending institutions. You used to have a grey area where you could negotiate and discuss; that has disappeared with the crisis. Codes of conduct and regulations are built upon the average man. It is really hard to get a mortgage when you deviate from these [codes of conduct].’ (Respondent NL-G, mortgage broker in the Netherlands, March 2019)

The standardisation and tightening of lending regulations targeting ‘the average man’, mean that households who are able to secure a mortgage are the ones who present higher average credit scores and income levels. This makes homeownership less accessible to an increasingly larger group. In effect, the stricter regulations in both Canada and the Netherlands, combined with a sharp increase in housing prices (fuelled by years of loose lending practices and more recent anti-crisis measures) had a strong socio-economic effect. They ended up excluding non-prime households with lower income levels, bruised credit scores or precarious working arrangements from the owner-occupied housing sector.

Especially the younger generation that began their entry into the housing market after the GFC, was largely unable to profit from the sharp increase in property values over the last years, and has had a hard time entering the owner-occupied market. Respondent NL-C, mortgage and risk expert at the Dutch Central Bank, acknowledges these effects:

‘You can see that young people have an increasingly hard time getting a mortgage (…) it used to be a lot easier. Now people need to save money for a long time, get a permanent job… And that takes long… Yes, that’s a disadvantage…’ (Respondent NL-C, mortgage and risk expert at the Dutch Central Bank, March 2019)

In order to cover the costs that can no longer be included in mortgage loans, prospective mortgage holders need capital resources of their own. In Canada this is further amplified by the required down payment of a minimum of five percent. In both countries respondents indicate that many owner-occupied households received financial help from their parents:

‘Parents put in a lot of money, they can gift up to 100.000 euros tax-free. You see this a lot. Otherwise it’s impossible for people to buy a house. Often, parents borrow these 100.000 euros against their own property with high home equity, and then donate this sum to their children. Refinancing? Nobody worries about that!’ (Respondent NL-D, independent mortgage broker in the Netherlands, March 2019)

This phenomenon increases the gap between households with and without (parental) wealth, while increasing risk in the refinancing of the mortgages of those who provide the down payment (usually the parents). Especially in Canada where households that are able to arrange a down payment of 20 percent are not required to insure their mortgage and therefore do not have to comply with federal regulations.

This new measure also perpetuates and even intensifies intergenerational privileges and intergenerational inequality, since tapping into personal or parental wealth is not an option for most households. In both countries mortgage brokers indicated that the combination of strict mortgage regulations and stress on the housing market leads some people to make what they call ‘unwise’ decisions. In Vancouver a mortgage broker with a predominantly Filipino migrant clientele admitted that adding adult children to the contract is conventional. In these cases instead of wealth, debt is passed on to the next generation in order to obtain a mortgage;

‘If people are desperate, then you have to find strategies (…) There are ways. (…) The first thing I'm going to ask is ‘how old is your child? What do they do?’ Let's add them [on the mortgage contract]. (…)’ (Respondent CA-M, mortgage specialist at a major bank in Vancouver, November 2018)

Other ‘unwise’ strategies practiced in both Canada and the Netherlands included borrowing money to close a mortgage, while telling lending institutions that it was a gift, hiding debts (especially student debts in the Netherlands that are not nationally registered) and bidding far above the market value of a property. These are not novel strategies, but all mortgage brokers indicated seeing an increase in these kinds of tactics since the stricter regulations began. Respondent NL-M, CEO of a mortgage lending institute, notes:

‘Starters now need around 15 to 20 thousand euros of private capital to fund a mortgage. (…) so people need to come up with something. Personal loans, informal loans between their private and company’s account, revolving credits [e.g., credit cards]… People will look for possibilities (…)’ (Respondent NL-M, CEO of Dutch mortgage lending institute, March 2019)

One of the most risky practices linked to efforts to go around new mortgage regulations in Canada, is the fact that some households who no longer qualify for a mortgage in the regulated lending domain turn to unregulated private lenders. These lenders (usually individuals, syndicates or mortgage investment companies), are not federally regulated and, therefore, do not have to comply with mortgage lending guidelines. They typically offer short term interest-only mortgage loans with much higher interest rates (between 10 and 18 percent) and charge expensive service fees. Respondent CA-D, mortgage broker and private lender in Canada explains how his business model works:

‘If people go to private lending, it's because they don't qualify with a conventional lender. If they would go to Scotiabank [major bank in Canada], Scotiabank would say “no, your credit score is too low”, or “you don't claim enough money on your income tax”, “you are self-employed”, “you haven't been in business long enough”, or they just have too much debt. And they come to me (…) and I'll do that. (…) Private lending focuses more on the property, and less on the clients. (…) they will look at the property and will say, “okay, well, if the client chooses not to pay their mortgage… Then we can come in and foreclose the property, and then just take the property, sell it and get our money back”. So, it's not such a concern.’ (Respondent CA-D, mortgage broker and private lender in Canada, November 2018)

The increased popularity of private lenders in Canada was confirmed by the analysis of the unpublished minutes (provided to the authors by respondent CA-B, employee at CMHC) of meetings organised by CMHC with a large number of private lenders in Canada. Not only do the data sources show that private lending is becoming more popular, but also the role of these alternative lenders seems to be transforming. Private lenders used to fulfil primarily a temporary role in the mortgage field, providing loans to clients in high need, often due to divorces or other life changing events. Typically, the client would transition (back) into the traditional mortgage market after their one-year term ended. However, increasingly, private lenders are offering mortgages with two- or three-year terms. Private lenders are seeing more clients renewing their mortgages after the first term ends. This leads respondent CA-B, government employee for CMHC, to suspect that due to increasingly tight regulations, private lenders are starting to fulfil a more permanent role in the mortgage field:

‘So these guys [private lenders] are kind of acting as [buffers for] people that need money for their home (…) they are helping these guys out short term (…) Now, because of the recent changes, because they are seeing more and more clients to the private lending cycle (…) [and] people are not so much able to go back [to traditional lending sources].’ (Respondent CA-B, government official working for CMHC, November 2018)

There is very little additional, quantitative data on the private lending sector, precisely because it is unregulated and thus does not have to report its activities publicly. However, recently, Teranet (the land registration provider of Ontario), analysed the share of private lending for the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The report indicates a growth in the number of households turning to private financing options in the period between 2016 and 2018. Since 2016, the year the stress test was introduced for insured mortgages, mortgages sourced by private lenders grew from 4.9 to 6.8 per cent. Additionally, it shows a large increase of 67 percent of the share of private lenders offering refinancingFootnote3 mortgage transactions (Pasalis & McGowan, Citation2018). Although the findings in the Teranet study on Toronto are by no means directly transferable to Canada as a whole, it does indicate that private lending has increased in popularity. This matters as the typically higher interest rates within private lending schemes put more pressure on households trying to keep up with their mortgage payments. This is a matter of particular concern, and warrants further research, considering that clients of private lenders are, in general, households that cannot apply for a conventional mortgage because of debt problems and/or low- or unreliable-income streams.

This emergence of unregulated private mortgage markets is a significant point where the Netherlands and Canada case studies contrast. In the Netherlands, all mortgages have to comply with regulations, therefore a formal ‘private’ mortgage market does not exist officially. Still, one of the Dutch mortgage brokers who we interviewed, indicated that he has seen an increase in people trying to fund their whole housing purchases through private loans:

‘More and more people use private financers to fund their purchase; private money. They can lend it to whoever they want, there is no regulation for that… Maybe to people with poor credit scoresFootnote4, or self-employed who started recently but have a good prospective…’ (Respondent NL-D, independent mortgage broker in the Netherlands, March 2019)

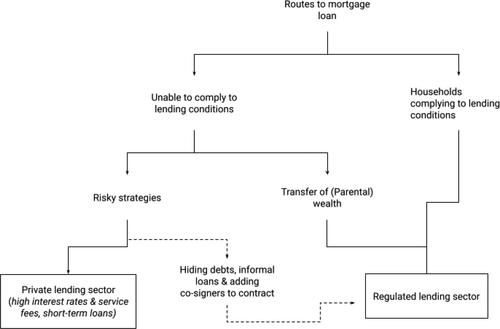

The other Dutch mortgage brokers who we interviewed did not recognise such a trend. But as these types of loans are not officially mortgages, mortgage brokers are not necessarily au fait with what is happening outside the official mortgage lending market. Further research is needed to assess to what extent this is occurring in the Netherlands and what the implications for low- and middle-income households are. displays the simplified routes to mortgage loans in Canada and the Netherlands.

Implications for mortgage lending institutions

The increase in housing prices that pose challenges for starters and/or less financially resourceful households, also enhance the appeal of mortgages and housing as investment products. A report by the Dutch Central Bank shows that competition in the Dutch mortgage market is growing, as multiple lenders entered the market in the past years (DNB, Citation2016). Particularly, the share of non-banking institutions is increasing. The CEO of a new, but significant, mortgage investment fund explains that the demand for investing in Dutch mortgage products is high:

‘In our initial business plan, we were told we needed 500 million to start our fund and originate mortgages. Well, our first deal already included 2.4 billion euros. It was crazy. The need was much greater than we expected (…) now a total of 21 pension funds are investing in our fund for a total of 13 billion dollars. That’s huge. Almost 60.000 mortgages. That’s the size of a middle-sized Dutch city.’ (Respondent NL-M, CEO of a Dutch Mortgage Investment Fund, March 2019)

According to the respondents interviewed in the Netherlands, mortgages are attractive because of the general low-interest environment, their excellent track record during the crisis (low arrears and foreclosure numbers, despite negative equity issues), government guarantee, availability of data and homogeneous character. The post-crisis tightening of lending criteria and the restriction of interest-only products have contributed to the attractiveness of mortgages as an investment product. This is further amplified by the current low-interest environment. In Canada similar mechanisms can be identified. Respondent CA-A, senior government employee at CMHC, points at the effect of lowering interest rates:

‘So, I think low interest rates have certainly [contributed to increasing house prices], the real cost of money is pretty low (…) it makes housing a really attractive and safe investment all together. So that means that there is an overallocation of credit to housing markets, (…) collectively we are putting more of our savings into bricks than microchips and whatever else…’ (Respondent CA-A, government employee at CMHC, November 2019)

This led him to think that the state interventions responding to the GFC are predominantly impacting borrowers, and not necessarily the investment opportunities:

‘I don't think the power of the market is… [curtailed], I mean most of the post-crisis stuff affects relatively small investors, people buying their own home (…) I think there are still wealthy powerful people that speculate on land and are in a position to, I don’t know, at least have significant control over available land.’ (Respondent CA-A, government employee at CMHC, November 2019)

Mortgage brokers both in Canada and the Netherlands recognise that real estate still serves as an excellent place to absorb surplus value and attracts many private and institutional investors. This is especially true in the case of returns on deposits where savings are minimal due to the low interest environment. Aalbers et al. (Citation2018) already found that buy-to-let investment in Amsterdam almost doubled from 7 to 13 percent. Respondent NL-I, mortgage broker in the Netherlands sees this too:

‘In the last two to three years, you can see a huge increase in interest in investment objects. Especially buy-to-let… As your savings currently give zero returns at the bank, and everyone hears the story about the sheer increase of prices on the housing market…’ (Respondent NL-I, independent mortgage broker in the Netherlands, April 2019)

Respondent CA-L, manager of a team of mortgage brokers a major Canadian bank, sees a lot of investor customers, especially in Vancouver:

‘(…) there are definitely more investor customers in Vancouver than there are in the rest of Canada. (…) And what I mean by that is, not only are they buying their primary residence home, but they are also buying investment property. (…) That mindset of making money on real estate here, is more so than other parts of Canada where your mindset is “oh I got to find my home”. Here it is “oh I got to buy my home” and “oh let me invest as well.”’ (Respondent CA-L, manager mortgage broker team at a major bank in Canada, November 2018)

The respondents highlight two developments that add to the popularity of real estate investment: the general low interest-environment that lead small and institutional investors to look for other investment opportunities, and the steady growth of real estate values.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examined the remarkably similar post-crisis stories related to the Canadian and the Dutch mortgage markets. We argued that, although the Global Financial Crisis exposed some of the vulnerabilities of the financialisation of housing markets, the state interventions put in place in response to the crisis, actually failed to delink housing from the practices of global financial markets. We illustrated three key points.

Our first key point is that the re-regulation of mortgage debt after the crisis played an important role in reviving capitalist accumulation regimes as both national governments mobilised mortgage debt to mitigate the effects of the crash. In both Canada and the Netherlands, lending was encouraged through expanding government guarantee schemes and lowering interest rates. Liquidity was, furthermore, directly injected into the mortgage sector by buying off underperforming mortgage loans. The relatively good performance of mortgages and the speedy post-crisis recovery of house prices attracted investments in both cases, especially in urban areas such as Vancouver and Amsterdam. Mainstream analyses of the GFC argue that mortgage debt was a main source of the financial crisis. In this article, we show how mortgage debt was also used as a ‘cure’ out of the crisis, leading eventually to even further increase in housing prices. This illustrates how the increase in prices is not a natural process, or solely an effect of supply and demand dynamics, but a consequence of the central role that housing plays in institutional and regulatory arrangements that support the global financialised economy. While the next global crisis of COVID- 19 is unfolding the Canadian government has, in an effort to mitigate economic effects, already started to expand its state securitisation programmes again. Just as in the aftermath of the GFC this could further cheapen the costs of credit and contribute to further increase of house prices and indebtedness.

The article’s second key contribution is the analysis of how the re-regulation of mortgage markets after the crisis further increased the exchange value of mortgage products. In an almost perverse manner, the re-regulation of the mortgage markets only intensified the financialisation of housing and contributed to further increase in housing prices and the maturing of the mortgage market as a profit making market unto itself. By using their deep involvement in the mortgage sector, lending terms were standardised and tightened. The total borrow capacity was decreased and access to capital restricted for non-prime households with lower income levels, bruised credit scores or precarious working arrangements. Local specific mortgage products were discouraged, creating a more homogenous pool of attractive low-risk debt products to be easily traded on global capital markets. Especially in combination with the lack of other investment opportunities, this led local, global, private and institutional actors to invest in real estate and mortgage products in both Canada and the Netherlands.

The third key point we make in the article is that the new regulatory regimes intensified the fault lines between the prime households that are able to enter the owner-occupied sector, and the non-primes that are not. This confirms earlier research on the increased barriers to mortgaged homeownership (Arundel & Doling, Citation2017; Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2015; Hochstenbach, Citation2017; Jonkman & Janssen-Jansen, Citation2015; Lennartz et al., Citation2016). Adding situated knowledge from the perspective of mortgage market professionals we showed how in both Canada and the Netherlands, households that are excluded from regular mortgage lending – because of the state interventions in the mortgage market – make use of risky strategies to access mortgaged housing. Hiding debts, informal loan agreements, and adding co-signers (children and other relatives) to a mortgage contract are the practices that households turned to. In Canada an unregulated (expensive and risky) mortgage sector is growing, functioning as a last resort for households that are now excluded from the traditional lending market. In some ways the private lending sector resembles the subprime mortgage practices that preceded the GFC. The key difference is that the current private originated mortgage loans, in general, are not securitised on the global capital market, hence the risk takes place mostly at the household level rather than by global lenders. In the Netherlands signs of such practices were found, but more research is needed to substantiate this trend. The findings indicate that the re-regulation of the mortgage market leads to a more risk-averse environment for lenders and investors as Forrest and Hirayama (Citation2015) claim, but also show that a risk-prone environment emerges for (prospective) mortgage holders that do not fit the profile of the ‘average man’.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the journal editor for their valuable and productive suggestions. Many thanks also to Prof. Tuna Taşan-Kok for commenting on an earlier draft of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The portfolio was worth 27 billion euros in total, 80 percent of which was guaranteed.

2 The ECB has the authority to set three interest rates; the rate on main refinancing operations (of which operation banks can borrow liquidity), the rate on deposit facility (which banks can use to make overnight deposits) and the rate on marginal lending facility (offers overnight credit to banks). The last two rates influence the interest rate at which banks lend to each other. All three interest rates were lowered during and after the financial crisis (ECB, Citation2019). Low interest rates make borrowing capital cheaper for financial institutions. This provides them with liquidity, and enables them to lend money with lower interest rates to households for example (e.g., mortgage loans).

3 Refinancing is the process of getting a second mortgage, either in addition to or replacing the first mortgage. The new mortgage is often used to get better mortgage terms, to pay off other debts or to ‘cash out’ home equity.

4 In the Netherlands loans are registered by Bureau Krediet Registratie (BKR). A BKR registration can influence the size of a new mortgage or, in the event of a negative registration, restrict new loans within the traditional financial system, although this is still possible with private lenders.

References

- Aalbers, M. (2008). The financialisation of home and the mortgage market crisis. Competition & Change, 12(2), 148–166.

- Aalbers, M., Bosma, J., Fernandez, R., & Hochstenbach, C. (2018). Buy-to-let: Gewikt en Gewogen. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Aalbers, M., Engelen, E., & Glasmacher, A. (2011). Cognitive closure’ in the Netherlands: Mortgage securitization in a hybrid European political economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(8), 1779–1795. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43321

- Andrle, M., Plašil, M. (2019). Assessing house prices in Canada: Borrowing capacity and investment approach. (Working Paper No. 19/248). International Monetary Fund.

- Arjani, N., Paulin, G. (2013). Lessons from the financial crisis: Bank performance and regulatory reform. (Discussion Paper No. 4). Bank of Canada.

- Arundel, R., & Doling, J. (2017). The end of mass homeownership? Changes in labour markets and housing tenure opportunities across Europe. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment: HBE, 32(4), 649–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-017-9551-8

- Ashton, P., & Christophers, B. (2018). Remaking mortgage markets by remaking mortgages: US housing finance after the crisis. Economic Geography, 94(3), 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1229125

- Barone, G., David, F., de Blasio, G., & Mocetti, S. (2020). How do house prices respond to mortgage supply? Journal of Economic Geography, 0, 1–14.

- Beswick, J., Alexandri, G., Byrne, M., Vives-Miró, S., Fields, D., Hodkinson, S., & Janoschka, M. (2016). Speculating on London's housing future: The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes. City, 20(2), 321–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1145946

- Bezemer, D., Grydaki, M., & Zhang, L. (2016). More mortgages, lower growth? Economic Inquiry, 54(1), 652–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12254

- Birrell, B., & McCloskey, D. (2016). Sydney and Melbourne’s housing affordability crisis report two: No end in sight. (Research Report No. 2). The Australian Population Research Institute.

- Boelhouwer, P. (2017). The role of government and financial institutions during a housing market crisis: A case study of the Netherlands. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(4), 591–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1357399

- Boelhouwer, P., & Schiffer, K. (2015). Kopers komen te kort! Naar een evenwichtige toepassing van de LTV-normen. OTB-Onderzoek voor de gebouwde omgeving.

- Carter, T. (2012). The Canadian housing market: no bubble? No meltdown? In A. Bardhan, H. Edelstein, & C. Kroll (Eds.), Global housing markets: Crises, policies and institutions (pp. 511–534). Wiley Online Library.

- CBS. (2005). Woninghypotheken; uitstaande schuld, 1989 - 2003 [Residential mortgages; outstanding debt, 1989 - 2003] [Data set]. StatLine.

- CBS. (2014). Nationale rekeningen; historie 1900 - 2012 [National accounts; history 1900 – 2012] [data set]. StatLine.

- CBS. (2019). Kerngegevens sectoren; nationale rekeningen [Key statistics sectors; national accounts]. StatLine.

- City of Vancouver. (2018). Housing Vancouver strategy. City of Vancouver. https://council.vancouver.ca/20171128/documents/rr1appendixa.pdf

- CMHC and Fundamental Research corp. (2015). Growth and risk profile of the unregulated mortgage lending sector. (Research Report). CMHC.

- CMHC. (2018). Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMB) Program [data set]. Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

- DNB & AFM. (2009). Risico’s op de hypotheekmarkt voor huishoudens en Hypotheekverstrekkers [risks on the mortgage market for households and mortgage lenders]. Amsterdam.

- DNB. (2010). In het spoor van de crisis [the track of the crisis] (2nd ed.). De Nederlandsche Bank.

- DNB. (2016). Kredietmarkten in beweging [Dynamic credit markets]. De Nederlandsche Bank.

- DNB. (2020). House prices are more closely related with borrowing capacity than with housing shortage. (DNBulletin report No. 5). De Nederlandsche Bank.

- Dol, K., van der Heijden, H., & Oxley, M. (2010). Economische crisis, woningmarkt en beleidsinterventies: Een internationale inventarisatie [Economic crisis, housing market and policy interventions: an international assessment]. Onderzoeksinstituut OTB, Delft.

- Dutch Banking Association. (2014). The Dutch Mortgage Market. Dutch Banking Association [Nederlandse Vereniging van Banken].

- Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. (n.d.). Regels voor hyptoheken [Mortgage regulations]. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huis-kopen/regels-voor-hypotheken

- ECB. (2019). Monetary policy decisions. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/decisions/html/index.en.html

- Engelen, E. (2008). The case for financialisation. Competition & Change, 12(2), 111–119.

- Engelen, E., & Glasmacher, A. (2018). The waiting game: How securitization became the solution for the growth problem of the Eurozone. Competition & Change, 22(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418758579

- Epstein, G. A. (2005). Financialisation and the world economy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fernandez, R., & Aalbers, M. (2016). Financialisation and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism. In M. Aalbers (Ed.), The financialisation of housing (pp. 81–100). Routledge.

- Forrest, R., & Hirayama, Y. (2015). The financialisation of the social project: Embedded liberalism, neoliberalism and home ownership. Urban Studies, 52(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014528394

- García‐Lamarca, M., & Kaika, M. (2016). Mortgaged lives’: The biopolitics of debt and housing financialisation. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12126

- Government of Canada. (2014). Economic action plan: The road to balance. Government of Canada.

- Government of the Netherlands. (n.d.). Aanpak financiële sector [Approach financial sector]. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/kredietcrisis/aanpak-kredietcrisis-nederland-financiele-sector

- Harvey, D. (2006). The limits to capital. Verso.

- Hochstenbach, C. (2017). State-led gentrification and the changing geography of market-oriented housing policies. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(4), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2016.1271825

- Huang, S. (2015). Displacing housing problem? Addressing housing crisis of Hong Kong in the restructuring Pearl River delta region. In Y. L. Chen & H. B. Shin (Eds.), Neoliberal urbanism, contested cities and housing in Asia (pp. 405–415). Springer.

- IMF. (2011). Durable Financial Stability: Getting There from Here. (Global Financial Stability Report No. April). International Monetary Fund.

- Jonkman, A., & Janssen-Jansen, L. (2015). The “squeezed middle” on the Dutch housing market: How and where is it to be found? Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 30(3), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-014-9420-7

- Jordà, Ò., Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2016). The great mortgaging: housing finance, crises and business cycles. Economic Policy, 31(85), 107–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiv017

- Justiniano, A., Primiceri, G. E., & Tambalotti, A. (2019). Credit supply and the Housing boom. Journal of Political Economy, 127(3), 1317–1350. https://doi.org/10.1086/701440

- Kadi, J., & Musterd, S. (2015). Housing for the poor in a neo‐liberalising just city: Still affordable, but increasingly inaccessible. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 106(3), 246–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12101

- Kaika, M. (2017). Between compassion and racism: How the biopolitics of neoliberal welfare turns citizens into affective ‘idiots. European Planning Studies, 25 (8), 1275–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1320521

- Kakes, J., Loman, H., & Van der Molen, R. (2017). Verschuivingen in de financiering van Hypotheekschuld [shifts in financing mortgage debt]. Economische Statistische Berichten, 102(4749S), 69–73.

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialisation of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Lennartz, C., Arundel, R., & Ronald, R. (2016). Younger adults and homeownership in Europe through the global financial crisis. Population, Space and Place, 22(8), 823–835. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1961

- Lennartz, C., Baarsma, B., & Vrieselaar, N. (2019). Exploding house prices in urban housing markets: Explanations and policy solutions for the Netherlands. In R. Nijskens, M. Lohuis, P. Hilbers, & W. Heeringa (Eds.), Hot property: The housing market in major cities (pp. 207–221). Springer Open.

- McLeay, M., Radia, A., & Thomas, R. (2014). Money creation in the modern economy. (Quarterly Bulletin No. Q1). Bank of England.

- Ministry of Finances. (2012a). Informatieblad- Veranderingen vanaf woningmarkt 2013 [Information on changes in the housing market from 2013]. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/brochures/2012/05/25/informatieblad-woningmarkt

- Ministry of Finances. (2012b). Staatscourant 2012, 26433 | Overheid.nl > Officiële bekendmakingen. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-2012-26433.html

- Ministry of Finances. (2018). Belangrijkste wijzigingen belastingen 2018 [Most important changes taxes 2018]. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/schenkbelasting/documenten/circulaires/2017/12/20/eindejaarspersbericht-financien-2018

- Murphy, L. (2011). The global financial crisis and the Australian and New Zealand housing markets. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 26(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9226-9

- OECD. (2018). Household accounts - Household debt [online data set]. https://data.oecd.org/hha/household-debt.htm. oi: https://doi.org/10.1787/f03b6469-en

- OSFI. (2017). Residential mortgage underwriting practices and procedures. – effective January 1, 2018. (No. B-20). Government of Canada.

- Pasalis, J., McGowan, P. (2018). The GTA Sees a Surge in Private Lending. (Market Insights No. October). Teranet. https://www.movesmartly.com/toronto-area-sees-a-surge-in-private-lending

- Piketty, T. (2015). About capital in the twenty-first century. American Economic Review, 105(5), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151060

- Roberts, A. (2016). Household debt and the financialization of social reproduction: Theorizing the UK housing and hunger crises. Risking capitalism. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Rolnik, R. (2019). Urban warfare. Verso Trade.

- Ronald, R., Lennartz, C., & Kadi, J. (2017). What ever happened to asset-based welfare? Shifting approaches to housing wealth and welfare security. Policy & Politics, 45(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557316X14786045239560

- Ryan-Collins, J., Lloyd, T., & Macfarlane, L. (2017). Rethinking the economics of land and housing. Zed Books Ltd.

- Scanlon, K., & Elsinga, M. (2014). Policy changes affecting housing and mortgage markets: how governments in the UK and the Netherlands responded to the GFC. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29(2), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9390-1

- Scanlon, K., Lunde, J., & Whitehead, C. (2008). Mortgage product innovation in advanced economies: More choice, more risk 1. European Journal of Housing Policy, 8(2), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616710802037359

- StatCan. (2019). Residential mortgage credit Table 10-10-0129-01 [data set]. https://doi.org/10.25318/1010012901-eng

- The Court of Audits. (2018). Algemene Rekenkamer, Historisch archief van interventies tijdens de mondiale financiële crisis [Historical archive of interventions during the global financial crisis]. https://rekenkamer.presurf.nl/public/20180409115858/http:/kredietcrisis.rekenkamer.nl

- The Court of Audits. (2019). Algemene Rekenkamer, Kredietcrisis [Credit crisis]. https://www.rekenkamer.nl/onderwerpen/kredietcrisis

- Tsatsaronis, K., & H. Zhu (2004). What drives house price dynamics: Cross-country evidence. BIS Quarterly Review (March), 65–78.

- Turffrey, B. (2010). The human cost - How the lack of affordable housing impacts on all aspects of life. Shelter.

- Van Gent, W. (2013). Neoliberalization, housing institutions and variegated gentrification: How the ‘Third Wave’ Broke in Amsterdam. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 503–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01155.x

- Walks, A. (2012). Canada's new federal mortgage regulations: Warranted and fair?. (Research Bulletin 46). Cities Centre.

- Walks, A. (2014). Canada's housing bubble story: Mortgage securitization, the state, and the global financial crisis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), 256–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01184.x

- Walks, A., & Clifford, B. (2015). The political economy of mortgage securitization and the neoliberalization of housing policy in Canada. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 47(8), 1624–1642. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130226p

- Wetzstein, S. (2017). The global urban housing affordability crisis. Urban Studies, 54(14), 3159–3177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017711649

- World Bank. (2019). GDP (Local Currency) Canada - World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files. [online data set].

- Yates, J. (2014). Protecting housing and mortgage markets in times of crisis: A view from Australia. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29(2), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9385-y