Abstract

In this study, we analyse the significant changes in housing policies and social welfare in Portugal and Ireland. Acknowledging the transformation of housing into a commodity, which has led to significant changes in the provision of social housing to low-income families, we show how these two countries, with distinct welfare systems and different patterns of retrenchment, had similar housing trajectories and pressures after the 2008 economic crisis. Using a comparative approach, our analysis shows Ireland and Portugal are not necessarily converging towards the same policy but evidence does suggest that both countries are moving their housing policy further towards financialisation. These results contribute to the understanding of how neoliberal housing policy has focused on state retrenchment and how financialisation has shaped social housing provision.

Introduction

The trend towards the financialisation of housing has seen countries moving away from the provision of social housing and an increased reliance on private market solutions. In this context, this article focuses on changes in welfare state and housing provision policies. It examines and compares social housing patterns in Portugal and Ireland, two countries with distinct welfare systems, relatively different patterns of retrenchment, and similar transformation pressures after the 2007/08 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), which further facilitated the entry of private developers and international corporations into the housing market. We use both a comparative and a historical approach to respectively discuss a) differences in social housing systems and welfare, and b) policy convergences/divergences in the processes of neoliberalisation and financialisation of housing. In using these complementary perspectives (Allen et al., Citation2008), we offer fresh insights into evolving policies of social housing provision, within the context of housing and financial markets. In other words, this article focuses on a comparative analysis of both the shared and diverging effects of housing policy retrenchment in Portugal and Ireland.

The rationale behind choosing the two case studies, Portugal and Ireland, was influenced by three factors that justify this choice – besides the fact that these two countries are rarely compared side-by-side. First, their distinct social welfare systems and particular housing transformation patterns allow for a rich and complex empirical field of comparative housing research. Second, they have much in common (i.e., strong catholic social values, semi-peripheral economics, weak local government). Third, both experienced serious shifts in social policy, including severe austerity measures due to the GFC which resulted in severe austerity policies and bailouts from the European troika which provided financial aid in exchange for an economic programme to contain the political and economic meltdown. In addition, the Portuguese and Irish states, as with other European countries, have moved from having roles as key agents in housing provision to subsidiary and regulatory roles (Norris & Fahey, Citation2011; Pinto & Guerra, Citation2013).

Definitions of social housing often present terminological challenges. As noted by Forrest (Citation2013, p. 304) ‘private, market, social, state [and] public are terms which are often used interchangeably’ in housing policy literature. Aiming to minimise this complexity, ‘social housing’ here refers primarily to a system providing long-term housing to a group of households specified only by their limited financial resources, by means of a distribution system and subsidies (Hansson & Lundgren, Citation2019). Similarly, definitions of social housing vary by country. In Ireland, the 1966 Housing Act refers to social housing as accommodation provided by local authorities or AHBs (Approved Housing Body or housing associations), which are independent, not-for-profit housing providers. In essence, social housing in Ireland is rented housing provided at below-market or subsidised rents by public or non-profit sector providers and usually allocated on the basis of need (Norris & Hayden, Citation2018). In Portugal, the meaning of social housing has changed, and the concept has been very inconsistent (Pato & Pereira, Citation2016). Most recently, social housing (also called ‘controlled cost housing’) is defined as housing built, rehabilitated or acquired with financial support from the State, which abides by limits on area and selling price or income (Institute for Housing and Urban Rehabilitation [IHRU], Citation2016; Ordinance law 65/2019).

Policy Context – Irish and Portuguese social welfare regimes

Ireland

Neoliberal policies in Ireland entail a shift towards fiscal consolidation and austerity at the level of macroeconomic policy and the consequent retrenchment and marketisation of welfare cycles (Byrne & Norris, Citation2019). The country gained international visibility during the ‘Celtic Tiger’ years, a period of rapid economic growth at the beginning of the 1990s up to the early 2000s (Kirby, Citation2010). As argued by O’Hearn (Citation2003), the ideological position of the 1990s was that the rapid growth was the outcome of neoliberal policies, including privatisation and responsible fiscal policies. The author points out that budgets after 1987 favoured tax cuts for the rich and failed to provide the necessary spending to address Ireland’s severe social problems, dismantling many social services. Ireland’s recent economic and social policies are fundamentally neoliberal in orientation, and this shift in orientation was made possible by the corporatist institution of ‘social partnership’ (see Baptista & O’Sullivan, Citation2008).

The 2007/08 GFC imposed severe stress on the Irish welfare state. While the government rushed to rescue the collapsing financial system, the process of state restructuring intensified. It encompassed a dual process of ‘rolling back’ and ‘rolling out’ numerous aspects of state activity, including welfare provision and regulation (Dukelow & Murphy, Citation2016, p. 19). The post-GFC in Ireland was marked by intense privatisation and marketisation of public services. An important example of marketisation within the public sector is the Irish activation policy (‘Pathways to Work’), which integrates Irish public employment services and income support and makes working age welfare more conditional (Collins & Murphy, Citation2016, p. 67). Another example is the greater reliance on the private sector in the delivery of social housing. The GFC consolidated a social housing provision model that gives a prominent role to private provision in several aspects of delivery and financing. Up to 1991, social housing was exclusively based on local authority tenure but it has declined due to successive tenant purchase schemes and the emergence (post-1990) of both housing associations and private landlords participating in a variety of rental subsidy schemes (Finnerty et al., Citation2016). During the 1990s and 2000s, social housing reached historic low levels in the country. Since 2014, Ireland has been in the midst of a housing crisis, with a significant undersupply of housing units and rising unaffordability (Byrne & Norris, Citation2019; Lima, Citation2020).

Portugal

The welfare state has been responsible for several changes and improvements in modern Portuguese society. Changes in areas such as social security, pensions, health, housing, education, disability and poverty are some of the main social rights that emerged from the mid-1970s onwards. The emergence of a set of constitutional social rights, in 1976, after the revolution, made the welfare state a key pillar of Portuguese society. Despite the international oil crisis in the 1970s, economic problems in the 1980s and two IMF interventions in 1977 and 1983, the welfare state expanded after European integration in 1986. The convergence to European social policies during the 1990s consolidated the improvements made in the welfare state and aided the development of the middle social classes (Rhodes, Citation1996). Decommodification and liberalisation in the 2000s inverted the welfare state boom of the previous two decades. Political debates targeting the revision of the constitution, cuts to pensions and reforms to public servant welfare, along with ideological debates, are some of the issues that emerged after the 2008 crisis.

Portugal experienced financial problems after the 2007/08 GFC and had to abide by the troika’s austerity programme. There was a sharp drop in economic activity and unemployment increased. Since 2009, Portugal has experienced recession, continued growth in public debt, austerity policies, the nationalisation of failed banks, the external intervention that comes with a bailout of the nation’s economy, difficulties in controlling the deficit, climate protests, and clashes between various institutions, including the government and the constitutional court, all caused by the economic crisis.

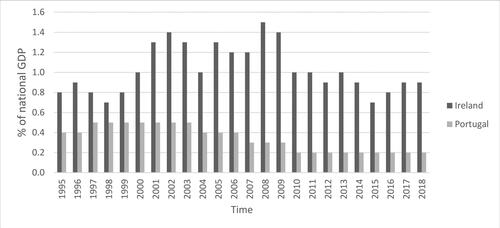

Taking Portugal and Ireland together, both countries have a highly developed system of social protection. presents a breakdown of total expenditure on housing for Portugal and Ireland over a period of 24 years. This figure presents interesting trends: in Portugal, public expenditure on housing has been less than 0.5% of GDP and decreased after the crisis, the period 2010–2018 showing the lowest value (0.2%). Ireland had a higher housing expenditure, consuming 1.7% of GDP from 2000–2010, and then followed the same pattern of decline as Portugal (Eurostat, Citation2020).

Housing patterns in Ireland and Portugal: the post-1980s period

Up to the 1980s, the housing strategy that Irish and Portuguese governments pursued was to stimulate housing production, including both social housing and homeownership (Cachado, Citation2013; Norris & Fahey, Citation2011). Given the scale of housing needs, the two countries adopted subsidies and policies of direct investment in housing production. But, similar to other European countries, the 1980s marked a new era of significant social change, greater economic volatility and severe fiscal pressures. Neoliberal policy reforms were geared towards containing housing expenditure and orienting state intervention so as to enable market-based housing provision, and so they became influential in the transformation of housing policy (Milligan et al., Citation2006, p. 241). In both Ireland and Portugal, the implemented policies and institutional structures established in the pre-1980 period influenced policy changes. This section presents the most relevant developments in terms of the neoliberalisation of housing policies in both countries.

The mid-1980s were a period when social housing in Ireland was redefined, marking the definitive retrenchment of this sector. When the economy stagnated, the expansive investment in social housing ended, and unemployment rose (Fahey et al., Citation2011). The solution focused on reducing public expenditure, with social housing being one of the early targets, and spending in this sector was cut back severely. The number of new builds, for example, fell from 7,002 units in 1984 to 768 in 1989 (Norris & Fahey, Citation2011). By 1987, local government was no longer borrowing from banks or through municipal bond issuers, and social housing finance was centralised. The central government abolished housing development loans and replaced them with capital grants, meaning it now had greater control over housing investment decisions (Byrne & Norris, Citation2019).

Whilst social housing in Ireland declined from the mid-1980s, the opposite trend occurred in Portugal from 1996 to 2005 with the launch of the large-scale Programa Especial de Realojamento or PER (Special Rehousing Programme), the largest social housing programme since the country’s democratisation. PER is estimated to have constructed almost 48,558 housing units (Allegra et al., Citation2017). The programme is particularly referenced for its relative success in terms of the direct promotion of social housing and the effective creation of the necessary conditions for its execution (Santos et al., Citation2014). Despite being acclaimed for having significantly reduced the number of slums, PER has also been the target of criticism, mostly related to the logic of mass housing (quantitative objectives instead of focus on housing quality and living conditions), and housing construction in peripheral areas, leading to the rise of dense neighbourhoods lacking facilities and infrastructure (Cachado, Citation2013). Portuguese social housing can be intended for rent or purchase (Decree-Law No.141/88). According to Vilaça and Ferreira (Citation2018), between 1984 and 2007, the National Housing Institute financed about 130,000 social housing dwellings, with 46% being for lease and 54% for purchase. Cooperatives were social housing promoters that built many dwellings, up to the mid-1990s. After the 1990s, municipal councils were the main social housing promoters through the PER for families living in shanty towns and in very precarious conditions in the Metropolitan Areas of Lisbon and Porto.

As indicated, by the mid-1980s, the function of Irish social housing had changed with radical cutbacks in funding and housing output, as the system moved towards the subsidisation of private rental housing. The foundations for the marketisation of social housing delivery in the private rental sector emerged initially in 1974 with the Rent Supplement (RS) scheme (Hearne & Murphy, Citation2018), designed as a short-term housing support for renting in the private sector. The RS scheme was means-tested and ceased when recipients entered full-time employment, creating an ‘unemployment trap’.Footnote1 Between 2000 and 2012, the number of RS claimants rose by 105%, when 87,684 households were recipients of the scheme at a cost of €422 million (Oireachtas, Citation2018). The issue was not only the number of new claimants, but the lengthy duration of the claims which, in many cases, was over 18 months. In the mid-2000s, several policy reforms were implemented to circumvent this issue, including the creation of the RAS (Rental Accommodation Scheme) for long-term rent supplement claims. The RAS had the explicit objective of supporting the expansion of the private rental sector (Norris & Coates, Citation2010). Later in 2014, the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) was established, allowing claimants to rent in the private sector, without restrictions on employment. HAP tenants have their rent paid by the government (Byrne & Norris, Citation2019) but are removed from social housing waiting lists, since they are considered to have their long-term housing needs met.

The Portuguese housing sector normally features few housing allowances. Differently from Ireland, where housing allowances are geared towards low-income households, Portuguese middle-income households are more likely than low-income households to receive a housing allowance, since housing allowances target households with a mortgage, e.g., subsidised loans and tax incentives (OECD, Citation2019). Only more recently, some municipalities, such as Lisbon, have implemented rent allowances for low-income families. After 2015, due to the liberalisation of the rental market, people over 65 years-old, disabled people and low-income families with rent contracts prior to 1990 could apply for rent allowances. The national programme, ‘Door 65 Youth’ (Porta-65-Jovem), for example, is a rent allowance targeting young people.

European integration has been central to financial liberalisation in both countries and it allowed the Portuguese and Irish financial systems to participate fully in the global financial sphere. In the 1990s in Portugal, EU banking regulations favoured the financing of home ownership through mortgages (Santos et al., Citation2018). A period of financial liberalisation started, with great incentives to promote home ownership with facilitated access to credit and a sharp increase in house prices during the building boom (Xerez & Fonseca, Citation2016). In Ireland, over recent decades, the subsidisation of housing policy has further contributed to the marketisation of the housing sector. While social housing production and delivery has shown significant signs of decline, the number of households in the private rental sector has consistently increased. As of 2016 (see ), the number of households in private rented accommodation accounted for 19.6% of all Irish households, growing by almost half since 2011, according to the latest 2016 census (CSO, Citation2018).

Table 1. Housing tenures in % (1960s–2016).

The expansion in mortgage debt is consistent with the rise in the proportion of property owners in Portugal, 73.2% in 2011, from 56.6% in 1981 (Pordata, Citation2018). In Ireland, the number of owner-occupied households went from 67.9% in 1981 to 77.4% in 2002 and then declined again to 69.7% in 2011 (CSO, Citation2016). The data also shows that homeownership in Portugal went from 56.6% in 1980 to 75.7% in 2011, remaining around the same level by 2011 (see ). According to the OECD, in 2017, 84% of promoters of social housing in Portugal were municipalities and 16% were national authorities. In Ireland, this ratio is 56% local authorities, 12% housing associations and 32% the private rental sector.

In a similar way to Ireland, housing in Portugal is characterised by strong incentives towards home ownership but low levels of social housing (Allen et al., Citation2008). In 2016, the social housing stock stood around 10% in Ireland and 2% in Portugal. Social housing delivery has declined in both countries. In Ireland, social housing provision fell 88% between 2008 and 2014, and output contracted from 7,588 units in 2008 to just 642 units in 2014, while investment in homeless services has increased three-fold in Ireland (Byrne & Norris, Citation2019; Lima, Citation2018). Portuguese social housing provision remains stable and boasts exceptionally high homeownership rates for the European region, but between 10–12% of units stand vacant and/or are slated for demolition, 3.4 per cent of which are dilapidated and uninhabitable (Farha, Citation2017).

In Portugal, the number of social housing dwellings increased by 1.2% from 2009 to 2011, representing around 2,000 new dwellings. In 2011, there were, on average, about 1,123 social housing dwellings per 100,000 inhabitants (Eurostat, Citation2020). Moreover, the 2012 Budget Law reduced support for home ownership, eliminating the fiscal benefits associated with reductions in interest rates. This change, linked to bank regulations on the handling of credit and mortgage defaults as defined by the EU, further restricted the most disadvantaged renters from entering the mortgage market. The reduction in the mortgage market has been beneficial to the expansion of the private rental market, which has grown since rent controls were lifted by the IMF bailout conditions in 2011. The changes included open-ended residential leases and the phasing out of rent control mechanisms. However, unlike Ireland, Portuguese private landlords are less involved in the provision of social housing.

The over-reliance on the private sector for housing provision – be it in terms of rent subsidies or housing construction – was confirmed as a trend after the GFC in 2008. Since then, the government of Ireland has embedded marketised social housing through rental schemes in its official housing policies. The entry of Real Estate Investments Trusts (REITs) is evidence of a new phase of financialisation with the heavy presence in the housing market of private equity funds and REITs in both Portugal and Ireland. These firms, known in Ireland as ‘vulture funds’, have acquired a vast amount of distressed property debt and are today among the biggest private landlords in Ireland, charging high rents and paying little tax (Lima et al., Citation2021). Similarly in Portugal, the presence of REITs has risen sharply, flooding the real estate market with international investment money in premium dwellings targeting high income earners. While housing research is beginning to understand the consequences of housing financialisation and the flipping of the meaning of ‘home’ to a ‘not-for-housing housing’ (Doling & Ronald, Citation2019), scholars have started to take note of the role of the state in the financialisation of housing and its links to homelessness (Lima et al., Citation2021).

Retrenchment and social housing

As the process of housing financialisation has deepened, so has social policy, which has drifted towards retrenchment. The strongest evidence for this is not just the withdrawal of the State from housing delivery, but also a housing provision model that encourages for-profit housing models. If, before the 1980s, housing policies sought to provide access to homes, over the years housing supports have become more than a support to assist households to meet the cost of housing, and they have become a primary source of wealth generation for private landlords. Portugal has narrower coverage compared to Ireland. But in both cases, social housing has been thrust aside and derided in both countries because more social housing is, in itself, an obstacle to private renting and the homeownership business.

Where social housing was allowed to exist, it was subject to stigmatisation, marginalisation and residualisation (Wacquant et al., Citation2014). In looking into the development of social housing in Portugal and Ireland, we found evidence that the decline of social housing stock over time has been justified by the need to create lucrative opportunities for investors and housing developers in both the homeownership and rental market. Our analysis is focused on the transnational trajectories in housing policy developments that inform social and welfare provision in Portugal and Ireland, so it is limited to particular national strategies. But as we place these countries in the international context of welfare reduction and housing financialisation, we are able to offer a macro-comparative perspective on the significance of welfare and social housing.

Conclusion

This research provides insights for the literature on social housing and neoliberal housing markets. We traced housing policy patterns and examined the retrenchment of the functions of the State in the context of the marketisation and financialisation of housing. In this way, this study adds to the growing body of research that indicates the rapid expansion in the financialisation of housing and retrenchment of welfare. Comparative approaches in housing research are still evolving, and along with the present research, this approach provides empirical evidence of housing policy moving towards financialisation. Being limited to two countries, this research excluded other jurisdictions going through a similar process, such as Spain, Italy, and Sweden. Notwithstanding this limitation, this work offers valuable insights into the most important features, and the development of and commodification of welfare provision and housing financialisation, contributing to the literature on comparative, place-specific processes. Future research could focus on the medium/long-term effects of national policy strategies and the impact of REITs in the subsided private rental sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 ‘Unemployment trap’ refers to situations where taking a job means lower earnings compared to remaining a recipient of state benefits. Programs such as the RAS and the HAP have attempted to address disincentives to taking a job with more flexible income-related criteria. See ‘Unemployment and Income Security’ by the International Labour Organisation.

References

- Allegra, M., Tulumello, S., Falanga, R., Cachado, R., Ferreira, A., Colombo, A., & Alves, S. (2017). Um novo PER? Realojamento e políticas de habitação em Portugal. Policy Brief. Lisboa.

- Allen, J., Barlow, J., Leal, J., Maloutas, T., & Padovani, L. (2008). Housing and welfare in Southern Europe. Wiley.

- Baptista, I., & O’Sullivan, E. (2008). The role of the state in developing homeless strategies: Portugal and Ireland in comparative perspective. European Journal of Homelessness, 2, 25–43.

- Byrne, M., & Norris, M. (2019). Housing market financialization, neoliberalism and everyday retrenchment of social housing. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19832614

- Cachado, R. (2013). O Programa especial de realojamento-ambiente histórico, político e social. Análise Social, XLVIII, 2182–2999.

- Collins, M. L., & Murphy, M. P. (2016). Activation: Solving unemployment or supporting a low-pay economy? In M. P. Murphy, & F. Dukelow (Eds.), The Irish welfare state in the twenty-first century: Challenges and change (pp. 67–92). Palgrave.

- Central Statistics Office [CSO]. (2016). Various years. Housing and households reports, census of population 2016. Ireland.

- Central Statistics Office [CSO]. (2018). Various years. Housing and households reports, Housing in Ireland Tenure & Rent. CSO, Ireland.

- Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (2019). Not for housing’ housing: Widening the scope of housing studies. Critical Housing Analysis, 6(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2019.6.1.450

- Dukelow, F., & Murphy, M. (2016). Introduction. In F. Dukelow & M. P. Murphy (Eds.), The Irish welfare state in the twenty-first century: Challenges and change (pp. 1–12). Palgrave.

- Eurostat. (2020). Various years. Housing and community amenities (COFOG) [gov_10a_exp].

- Farha, L. (2017). Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing. Mission to Portugal.A/HRC/34/51.

- Fahey, T., Norris, M., McCafferty, D., & Humphreys, E. (2011). Combating social disadvantage in social housing estates. Combat Poverty Agency. Ireland.

- Finnerty, J., O’Connell, C., & O’Sullivan, S. (2016). Social housing policy and provision: A changing regime? In F. Dukelow & M. P. Murphy (Eds.), The Irish welfare state in the twenty-first century: Challenges and change (pp. 237–259). Palgrave.

- Forrest, R. (2013). Reflections. In J. Chen, M. Stephens & Y. Man (Eds.), The future of public housing: Ongoing trends in the east and the west (pp. 303–310). Springer-Verlag.

- Hansson, A. G., & Lundgren, B. (2019). Defining social housing: A discussion on the suitable criteria. Housing, Theory and Society, 36(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1459826

- Hearne, R., & Murphy, M. (2018). An absence of rights: Homeless families and social housing marketisation in Ireland. Administration, 66(2), 9–31. https://doi.org/10.2478/admin-2018-0016

- Institute for Housing and Urban Rehabilitation [IHRU]. (2016). Habitação Social.Lisbon.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], various years. (1960–2016). Caracterização da Habitação Social.

- Kirby, P. (2010). Celtic Tiger in collapse: Explaining the weaknesses of the Irish Model. Palgrave.

- Lima, V. (2018). Delivering social housing: An overview of the housing crisis in Dublin. Critical Housing Analysis, 5(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2018.5.1.402

- Lima, V. (2020). The financialization of rental housing: Evictions and rent regulation. Cities, 105, 102787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102787

- Lima, V., Hearne, R., & Murphy, M. (2021). Housing financialisation and the creation of homelessness in Ireland. (Forthcoming).

- Milligan, R., Dieleman, M., & van Kempen, R. (2006). Impacts of contrasting housing policies on low-income households in Australia and the Netherlands. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 21(3), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-006-9047-4

- Norris, M., & Coates, D. (2010). Private sector provision of social housing: An assessment of recent Irish experiments. Public Money & Management, 30(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540960903492307

- Norris, M., & Fahey, T. (2011). From asset based welfare to welfare housing? The changing function of social housing in Ireland. Housing Studies, 26(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2011.557798

- Norris, M., & Hayden, A. (2018). The future of council housing: An analysis of the financial sustainability of local authority provided social housing. The Community Foundation of Ireland.

- OECD. (2019). Affordable Housing Database.

- O’Hearn, D. (2003). Macroeconomic policy in the Celtic Tiger: A critical assessment. In C. Coulter & S. Coleman (Eds.), The End of Irish History? Critical Approaches to the Celtic Tiger (pp. 34–55). Manchester University Press.

- Oireachtas. (2018). Rent Supplement Scheme Data - Dáil Éireann, 24 July.

- Pato, I., & Pereira, M. (2016). Austerity and (new) limits of segregation in housing policies: The Portuguese case. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(4), 524–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2016.1215962

- Pinto, T. C., & Guerra, I. (2013). Some structural and emergent trends in social housing in Portugal: Rethinking housing policies in times of crisis. Cidades, Comunidades&Territórios, 27, 1–21.

- Pordata. (2018). Contemporary Portugal database.

- Rhodes, M. (1996). Southern European Welfare States: Identity, problems and prospects for reform. South European Society and Politics, 1(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608749608539480

- Santos, A. C., Rodrigues, J., & Teles, N. (2018). Semi-peripheral financialisation and social reproduction: The case of Portugal. New Political Economy, 23(4), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1371126

- Santos, A. C., Teles, N., & Serra, N. (2014). Finança e habitação em Portugal. Cadernos Do Observatório, 2, 1–59.

- Wacquant, L., Slater, T., & Pereira, V. B. (2014). Territorial stigmatization in action. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(6), 1270–1280. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4606ge

- Vilaça, E., & Ferreira, T. (2018). Os anos de crescimento (1969‐2002), in: Cem Anos de Políticas Públicas Para a Habitação Em Portugal (pp. 11–40). IHRU.

- Xerez, R., & Fonseca, J. (2016). The housing finance system in Portugal since the 1980s, in: Milestones in European Housing Finance (pp. 310–324). Wiley.