Abstract

What is a politics of compassion, and what are the implications for the private rental sector? In this article, we describe how an intended politics of compassion manifested in Aotearoa during the pandemic and analyse how this compares to compassion’s theoretical framing in the work of Martha Nussbaum. Building on these theoretical insights, we then turn to practice, by analysing the vulnerabilities of, and barriers to, a politics of compassion evident in Government and landlord response to renters during the pandemic. We find a compounding of existing power inequity and the absence of compassion from political and administrative understandings in the face of neoliberal myths of the individualised market and fear of opportunism from those in poverty. We conclude with a discussion of the potential for a more compassionate private rental sector and make the case for an analysis of power, equity, and justice, in the theory and practice of a politics of compassion.

Introduction

What is the potential of a politics of compassion in achieving a more socially just private rental sector (PRS)? The intention of this article is to examine how the rhetoric of kindness influenced Government and landlord behaviour towards tenants during the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in AotearoaFootnote1/NZ (‘A/NZ’). The Sixth Labour Coalition Government began their period in office with the desire ‘to foster a kinder, more caring society’ (Ardern, Citation2017), a shift in values from the previous Government’s goal to ‘build a more competitive and internationally-focused economy with less debt, more jobs and higher incomes’ (Key, Citation2011). This was a new politics based on values of inclusivity and kindness, and included a specific intention to address the issue of housing, through policies that would ‘crackdown on speculators’ and ‘make life better for renters’ (Ardern, Citation2017). This study illuminates the degree to which these values and intentions played out in practice in the actual lives of tenants.

We explore the workings of ‘kindness’ in the individualised relationships between specific landlords and tenants, the ‘small stories’ (Smith, Citation2005), that illustrate how, at times, ‘rational’ behaviour expected by the market was subverted in response to crisis. We provide a novel examination of the potential of a theory and practice of the politics of compassion for addressing the inequalities inherent in the PRS, which are well documented in international housing literature. Our contribution is both theoretical and practical—we describe how an intended politics of kindness manifested in Aotearoa during the pandemic and analyse how this compares to compassion’s theoretical framing in the work of Martha Nussbaum. Building on these theoretical insights, we then turn to practice, by analysing the vulnerabilities of, and barriers to, a politics of compassion evident in the Government’s response to renters during the pandemic—including the compounding of existing power inequity, and its absence from political and administrative understandings in the face of neoliberal myths of the individualised market and fear of opportunism from those in poverty. We conclude by addressing how these barriers might be overcome and what a more compassionate PRS might look like.

We find that while some landlords took up the Government’s discourse of kindness during the crisis, the focus on individuals aligning their actions with ‘kindness’, with limited legal guidance, obscured the relative powerlessness experienced by tenants in negotiating security of tenure once they met the legal criteria for eviction. Just outcomes in housing during the pandemic became a question of whether a landlord had feelings of benevolence; in this way, compassion was intimately tied to power. The expression of compassion in legislation by Government was limited by concern for the property rights of landlords, and the disruption of the equilibrium of the market (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020a). A rise in rates of eviction was avoided, in part due to Government policy and kindness from some PRS landlords and, more significantly, from tenants becoming indebted to Government. We begin by examining some of the theory of compassion in politics.

Compassion in politics

Kindness was evident in the Government’s rhetoric towards the rental sector during the pandemic. The threat of mass evictions from income reduction and job losses led the Government call for landlords to act with ‘compassion’ and ‘kindness’, while concurrently making rapid changes to tenancy laws, including rent controls and restrictions on evictions, so that landlords would ‘respond to the environment we are in’ (Coughlan, Citation2020). In this section, we look briefly at why a politics of compassion is needed. Much housing studies literature examining the PRS sets out the inequity inherent in the PRS, especially noting lack of affordability (Morris et al., Citation2021; Power, Citation2019), precarity (Desmond, Citation2016; Chisholm et al., Citation2022; McKee et al., Citation2020), concerns with housing conditions (Chisholm et al., Citation2020), and power inequity (Byrne & McArdle, Citation2022). We propose that such inequities might be relieved by a radical politics of compassion.

Compassion is not always a familiar term in government and politics. However, it is similar to the concepts referred to by terms used by the A/NZ Government—‘kindness’, ‘empathy’ and ‘care’. Compassion is undergoing a ‘current rehabilitation [….] as political virtue’ (Ure & Frost, Citation2014, 1). There are some common goals in writings on the politics of compassion (Nussbaum, Citation1996; Whitebrook, Citation2002), and of love (Harris, Citation2017; Nussbaum, Citation2013), in the values underlying an ‘ethic of restoration’ in response to colonisation (Jackson, Citation2020), and in an ‘ethic of care’ (Smith, Citation2005; Power & Bergan, Citation2019). All have a desire to reframe caring and compassionate values and relationships, to shift these from their neoliberal compartmentalisation to the private life of the individual, into the social and public realm. As Nussbaum describes it, the politics of compassion seeks to move ‘the sort of daily emotion, the sympathy, tears, and laughter, that we require of ourselves as parents, lovers, and friends, or the wonder with which we contemplate beauty’ (2001, p. 397) into the way we shape our laws, politics, and markets.

Critics of these virtues in politics, of which Arendt (2006) is perhaps the most strident, argue compassion relies solely on the enmeshing of the compassionate with those suffering at an individualised level, is centred on the ‘self’ and, through strength of emotion, is detached from the ability to reason. When generalised across a group, it becomes pity, a weaker sentiment that demands no real action (Arendt, Citation2006). In Aotearoa ‘kindness’ has been criticised as a rhetoric that individualises systemic issues and acts as a “mechanism of control” (Asafo, Citation2021, p. 43). However, proponents of compassion argue it is one part of a complexity of motivations, and, though contextual and dependent on the level of suffering witnessed, is often a less ‘overpowering’ immobilising emotion than described by Arendt (Matthew, Citation2007; Nussbaum, Citation2001). Instead, it has a practical use as a means to motivate action beyond the individual towards social justice (Whitebrook, Citation2014) ‘provid[ing] imperfect citizens with an essential bridge from self-interest to just conduct’ (Nussbaum, Citation1996, 57).

In practice, a politics of compassion is mobilised through civic engagement in opportunities for empathy; taught through the education system, valued in good leadership, reflected in the economic and legal systems, and incorporated into public institutions—within the bounds of a democratic system (Nussbaum, Citation1996). The ability to feel compassion and solidarity with fellow beings is a means to achieve a more socially just society, a ‘recognition of systemic injustices where the focus is not on individual sufferers under the prevailing political system but on the system itself where it produces considerable suffering evident beyond the single case’ (Whitebrook, Citation2014, p. 26). In this article, we focus on the systemic injustices inherent in the PRS and explore how a politics of compassion, intended by Prime Minister Ardern, and theorised by Nussbaum, was operationalised during the pandemic.

The economic and policy context for rental housing in Aotearoa NZ

As in other nations, the pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities (Parsell et al., Citation2020; Rogers & Power, Citation2021; Rosenthal et al., Citation2020; Shadmi et al., Citation2020; Byrne & Sassi, Citation2022; Soaita, Citation2021). The A/NZ housing system has long favoured homeownership and, as in counties like Ireland, the UK, Spain and Australia, the leveraging of housing equity to expand investment into the purchase of second and subsequent housing to rent out (Adkins et al., Citation2020; Byrne, Citation2020). Given the absence of a comprehensive capital gains or wealth tax in A/NZ, landlords may rely on capital gains rather than rents. This had led to the ownership of housing becoming a greater determinant of wealth than employment, with housing prices appreciating faster than salaries. This indicates the makings of an ‘asset economy’ (Adkins et al., Citation2020), that excludes who rent. The effect of decades of housing policies favouring homeownership and property investment has been growing inequality between those who own their housing and those who don’t (Eaqub & Eaqub, Citation2015; Howden-Chapman, Citation2015).

Further inequities are reflected in A/NZ’s housing system, under strain from high rates of homelessness (Amore et al., Citation2020), an expanding public housing waiting list (HUD., Citation2021), a legacy of a depleted public housing stock (Murphy, Citation2020), problematic housing conditions (White et al., Citation2017), and an unsustainable rises in house prices (Stats NZ, Citation2020). Homeownership rates are the lowest in 70 years: a third of households rent and the majority of those doing so from the private sector (83%) (Stats NZ, Citation2020). Two-thirds of renters require some form of government financial support to maintain their tenancy (Stats NZ, Citation2020). Inequalities in housing follow ethnic patterns, with Māori, the indigenous people, more likely to rent the house they live in and to experience homelessness—a result of cumulative systematic disadvantage, continued racism (Houkamau & Sibley, Citation2015), and a process of colonisation that resulted in the majority of land being held by Crown or Pākehā by the middle of last century (Paul et al., Citation2020).

A politics of compassion situates these inequities as instances of suffering that demand action. It ‘assumes a shared humanity of interconnected, vulnerable people and requires emotions and practical, particular responses to different expressions of vulnerability’ (Porter, Citation2006, p. 99). Of course, in Aotearoa, as in other settler colonial states, a particular response is the necessary process of decolonisation (Jackson, Citation2020). The challenge for a compassionate and caring politics towards the PRS (rather than solely the public housing sector which has traditionally included an ‘ethic of care’ (Smith, Citation2005)), is to enable a market that addresses inequity, and, rather than commodifying housing, enables its primary value to be that of its use as a social good (Smith, Citation2005; Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016).

The rhetoric of ‘kindness’ in the Covid response

In her speech announcing the first national lockdown which would ‘place the most significant restriction on New Zealanders’ movements in modern history’ Prime Minister Ardern said ‘we will get through this together, but only if we stick together. Be strong and be kind’ (Ardern, Citation2020). Ardern’s strong compassionate leadership and ‘evidence-based response’ (Baum et al., Citation2021, p. 2) was widely commended as contributing to the overall success of the management of the pandemic (Baum et al., Citation2021; Mazey & Richardson, Citation2020). A/NZ’s approach to the COVID-19 pandemic was a swift closure of international borders and a ‘lockdown’ of households requiring all but essential businesses to close and for people to stay home to eliminate the virus from circulation (Wilson, Citation2020). The Government used persuasive messaging to gain support for these unprecedented restrictions on movement and civil freedoms (Jamieson, Citation2020; McGuire et al., Citation2020; Wilson, Citation2020). The strategy was to ‘unite against COVID’ (Ardern, Citation2020), to ‘go hard and go early’ (Jamieson, Citation2020) as a ‘team of 5 million’ to ‘save lives’ in order to ‘protect the economy’ (Wilson, Citation2020). Along with this, ‘be kind’ became the mantra of the pandemic, printed on public health material, and adopted into the daily lexicon. It was a rhetoric that aligned with existing indigenous values and practice—many maraeFootnote2 led community support, providing ‘unconditional manaakitangaFootnote3’ to ensure wellbeing (Davies et al., Citation2022).

It is therefore not surprising the discourse of kindness extended to advice on how to manage rent arrears in the PRS. Landlords and tenants were encouraged to ‘continue to be kind and work together where possible to reach an agreement’(Tenancy Services, Citation2021). Ardern called for landlords to be ‘fair minded’ and for commercial landlords to ‘work with your tenants, and just be a good human being’ (Molyneux & Lynch, Citation2020). Tenants were in a precarious position prior to the pandemic with a shortage of rental properties and landlord ability to issue a no-cause termination notice.Footnote4 There had been a 50% increase in the public housing waiting list between June 2019 and June 2020 (MHUD, Citation2020b) and the Government was eager to avoid further pressure on public and emergency housing (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020a).

This precarity was exacerbated by the pandemic, with those on a low-income more likely to have lost income than other groups (Fletcher et al., Citation2022; Versey, Citation2021). A total of 37,000 jobs were lost in April 2020, and main welfare benefit recipients increased by 47,000 between the end of February and May 2020 (Frischknecht, Citation2020). In the September quarter there was a 35.2% increase in unemployment compared to June, rising from 4% to 5.5% (Statistics NZ, Citation2020). Expecting landlords would not adequately support tenants (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020a), A/NZ, like other governments in high-income countries, moved rapidly to remediate the worst effects of the pandemic on low-income households and renters (Malpezzi, Citation2022; Pawson et al., Citation2022).

A government loan available to cover rent arrears was increased from $2000 to $4000 until 31 December 2020. In response to the pandemic the business of the Tenancy Tribunal was limited to hearing essential cases. Orders to end tenancies once the lockdown was announced were invalidated. ‘No cause’ tenancy terminations were prohibited for three months in recognition it was ‘a significant change to current landlord property rights’ (MHUD, Citation2020a). Tenants could have their tenancy terminated under special circumstances, including for rent arrears of 60 rather than 21 days. Tribunal adjudicators could refuse to terminate a tenancy if the tenant was making a reasonable effort to repay rent, or if termination would not be justified.Footnote5 A tenancy could also be terminated by consent of the tenant. However, movement during the lockdown period was only permitted by court order, or in cases of emergency, to give effect to public health restrictions. Possession orders granted during the lockdown were rare; most were timed to come into effect once initial restrictions were lifted on the 27th of April 2020. This limited the scope of action available to landlords and they were largely ‘stuck’ with their sitting tenants for the lockdown.

For those in employment, the key COVID-related welfare mechanism was a wage subsidy. Eligible employers who had lost 30% and later 40% of their income could apply for $585.80 per week as a grant for each full-time employee. Employers were expected to pay 80% of the worker’s usual wage if they were able, though not all did. The intention was to make the subsidy ‘trust-based’ to enable widespread uptake (Rosenberg, Citation2020). Little proof of income loss was needed, though a record of finances was required to be kept to prove compliance in event of an audit (Rosenberg, Citation2020). As of September 11, 2020, the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) reported the total wage subsidy amounted to $13.9bn and had paid for 1.8 million jobs (Wong & Wong, Citation2021). There was no obligation to pay the subsidy back from future revenue, even in circumstances of substantial profit-making.

The Government also intervened to ensure security of tenure for homeowners and to stabilise the risk of a fall in house prices, which were feared could have ramifications for the overall health of the economy because of the amount of debt owed on property. A mortgage holiday for homeowners was introduced and loan-to-value restrictions on house purchases were removed. Contrary to predictions, house prices rose between July 2020 and 2021, increasing 25% across NZ and 39% in the capital city, Wellington (REINZ., Citation2021). It was in this context that landlords, tenants, and the Government negotiated instances of rent arrears and financial hardship in the rental system.

Research methodology

Social constructionism and language

We focus on the motivations and attitudes informing the actions of Government and landlords to examine the relative role of kindness in comparison with other drivers. Our focus on the assumptions informing behaviour leads us to a study of discourse and language, which is ‘important in understanding how we perceive and make sense of the social world’ (Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2000, p. 37). Examining language and discourse is a means of ‘studying the social construction of normative (as well as resistant) representations and legitimations of social reality’ (van Leeuwen, Citation2018, p. 141). We use a particular form of social constructionist theory that assumes an ‘individual’s experience is an active process of interpretation’ (Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2000, p. 36). This is an approach employed in previous work (Bierre & Howden-Chapman, Citation2020) and one that is useful for the study of the social world and examining the construction of the issue of rent arrears, assumptions about landlords and tenants as actors, and beliefs about appropriate behaviour and policy.

Data collection

Interviews

Semi-structured phone interviews were held with self-selecting landlords who answered advertisements on social media. Interviews focussed on their experiences and actions during the first lockdown with follow-up questions seeking to understand why decisions were made. These included asking respondents to talk about why they became a landlord, their experiences of being a landlord during the first lockdown, and why they had decided on certain points of action. We spoke to 16 landlords—12 of whom owned two or fewer properties, and four who owned three or more. The interviews provided a rich description of the rental experiences of COVID-19, with coding and themes identified in the data also reflected in analysis of the forum discussion, a complementary data source—a pragmatic and quality drive definition of saturation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). All participant names are pseudonyms. Self-selection may have meant we spoke to landlords who felt strongly about the issue; however, this was balanced by the study of the online forum.

Online forum

We selected a thread from an online forum seeking advice on rent reductions for a tenant due to COVID-19 in 2020. This attracted 137 responses and 17,801 views by 2 September 2021. Discussion on the forum is free and frank, with members asking for advice and others offering opinions and experiences. It provided a complementary data source to the self-selecting landlords and was a source of ‘naturalistic data’ and ‘everyday conversations’ (Jowett, Citation2015, p. 288). While it is a public forum and most members use a pseudonym, some do not. For this reason, we adopted ethical considerations suggested by Shaw (Citation2020) and paraphrased discussion to protect the identity of contributors.

Analysis

We analysed these data sources using a reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2021). Our process was iterative—we began transcribing and coding our data in NVivo as soon as the first interview was completed and undertook ‘a continual bending back on oneself—questioning and querying the assumptions we [made] in interpreting and coding the data’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, 594). Our analysis was guided by a central research interest, how the discourse of kindness shaped landlord and Government actions and decision making. We used NVivo to categorise the data into initial descriptive codes focussed on action (e.g., negotiating), which were then analysed to identify themes related to the reasoning and motivations for these actions, paying close attention to the use of language. We focus on these landlord and Government experiences in the results that follow.

Results

The ethic of self-sufficiency and the profit-maximising individual

Decision making on whether to assist tenants was, in part, influenced by the rationale that landlords had for being in the market. For many, property investment was a way of becoming independent from the state and avoiding the intergenerational inequalities of high house prices. Landlords invested to ‘look after my children’ (May, Anna, Stella), ‘secure our own family’s future’ (Jess), or because ‘I don’t want them [children] being renters’ (Jan). It was a rational decision encouraged by a system offering tax-free capital gains; ‘for someone on a high salary with a high tax bracket investing in residential property in NZ was a rational thing to do’ (Sam). It had brought surprising levels of wealth; ‘we didn’t have any money [and] borrowed against our own house for both, bit like going to the pokies or something [….] now we have houses worth 1.7 − 1.8 million’ (Jan).

An ethic of self-sufficiency influenced landlords’ decision to help their tenants. Fourteen of the 31 landlords on the property investment forum thread did not favour assisting tenants with rent. As in the interviews, some were surprised at the lack of savings tenants had to get them through hard times; others felt tenants should get support from friends and family. In each situation, it was the landlord deciding whether to assist and how deserving the tenant was.

Expecting tenants to act opportunistically

Landlords and the Government feared tenant requests for assistance was opportunistic. While the Government set out to ensure renters could maintain their tenancies, they proceeded with caution. While laws were enacted to ‘sustain tenancies to the greatest extent possible [….] at the same time it is not acceptable for tenants to abuse the current situation by refusing to pay rent’ (MHUD, Citation2020a). There was worry about opportunistic tenants (and landlords) taking advantage of rent arrears assistance being a grant rather than a loan:

We recognise that this may mean that some households may take on additional debt as a result, and that this may act as a disincentive for some households to seek rent arrears assistance. However, this risk should be set against a significant risk of perverse incentives for both tenants and landlords which could result from making the payment non-recoverable. (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020b)

Overall there are key trade-offs that need to be managed in the post COVID-19 lockdown period to ensure the rental market recalibrates effectively. Trade-offs include ensuring that people can remain safely housed at a time when they may be facing severe economic hardship and allowing rental markets to find a ‘new normal’ or equilibrium without too much of a distortionary effect from government support (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020b).

Landlord decision making could also reflect mistrust and fear, rather than compassion. Gill’s property manager was approached by a tenant for a rent reduction, which Gill refused. She felt the tenant was taking advantage of the situation:

We got the feeling that they were just testing the waters for basically, well, if I don’t have to pay, I don’t have to pay (Gill).

When applying for this [RAA] support, applicants will continue to be encouraged to engage with their landlords to discuss the possibility of negotiating a rent repayment plan, rent deferrals or a possible lowering of rent (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020b).

Three months later the property manager informed Gill the tenant had moved out. Gill never met the tenants and had no knowledge of their reasons for missing rent—she had no personal basis on which to show sympathy. Fear tenants might use the crisis to skip rent was shared by other landlords, including forum members. Jan, who was somewhat conflicted, stated she ‘didn’t want to allude to them not paying rent, I didn’t want to give them the idea they could not pay rent because I still had bills, but we were certainly prepared to help them if need be’. Jody was franker:

I wrote to all three tenants and said look this is where we’re at. We have to keep paying for everything. We don’t want to lose the house but, in saying that, if you can’t pay the rent give us plenty of warning.

Tenant reluctance to appear opportunistic

Appearing opportunistic may have had an impact on tenant behaviour. It is notable that all landlords interviewed proactively contacted their tenants to check if they needed assistance. However, the nature of this contact varied. Sam approached her tenant as she was not sure they would contact her:

Well, I knew that tenant was a small business owner who wouldn’t be able to earn any money through her business at the time, so I approached her, and I offered her a $100 a week discount off the rent for that period, which was a token, but I did that for the duration of I think six months. I didn’t wait for her to come to me. I don’t know if she would’ve (Sam).

Not everyone needing help contacted their landlord. One participant, who was a landlord and a tenant, described reluctance in contacting her landlord for fear of risking the tenancy:

I’m really nervous he is going to turn around and go—actually we are going to put it on the market now. You feel so vulnerable as a tenant (Lucy).

The pull of collectivist ethics and kindness in crisis

This mistrust of tenants contrasted with landlords who provided help based on kindness, the idea of a shared experience in crisis and the provision of rental housing as a social service. There was a feeling of service described by landlords as a co-benefit to owning a rental property. Those supporting their tenants referred to an unprecedentedly difficult time for everyone in which people had a duty to help each other out. Landlords talked about ‘the whole world being turned upside down’ (Anna), a time when ‘you should help others’ (Dan), where people ‘saw the hardship, with people losing jobs’ (Lisa), and needing to support tenants going through (hopefully, a temporary) trying time (Forum). On the forum, just under half of respondents were supportive, or had actioned the idea of giving tenants some rent reduction or deferral, especially for tenants who were ‘long-term’, ‘good’, ‘nice’, or a ‘family’. This was encouraged by tenancy services who later asked landlords to ‘consider [the] tenant’s history with you’ (Tenancy Services, Citation2021).

There was compassion for tenants who had not caused their lost income (Forum). One forum member described their tenant as a ‘poor bugger’—a significant expression of sympathy in NZ. Jess, a landlord with one property, gave her ‘tradie’ tenant a reduction in rent, empathising as her husband was a builder and had lost work. They calculated they would be able to get by with Government grants and the wage subsidy:

He is a tradie and we knew he wouldn’t be able to work at all and so, would have no income. [….] We said, “okay, for the first four weeks, you can have half rent and we’ll discuss it further on.” (Jess)

A sense of ‘moral responsibility’ (Kate) led some landlords to consider how they would support their tenants if needed. Jan decided she’d drop the rent by $100 if asked, ‘Because I like my tenants [….] they pay their rent on time, they’ve been in there for two years’. Mary deducted a week’s rent from her six tenancies, an amount she felt she could afford, though her tenants had not requested assistance. Dan was asked by his tenants for a reduction in rent and negotiated an outcome he felt worked well:

They were gonna lose half of their income and then it goes down to 75%. So, they said, is there anything we can do? They were our long-term tenants. [….] In the end, we decided, we are all in the same boat, so we gave them a 50% rent reduction for three months. They volunteered during lockdown to paint the outside of the house. So, it worked out well (Dan).

Tenants take on debt to remain housed

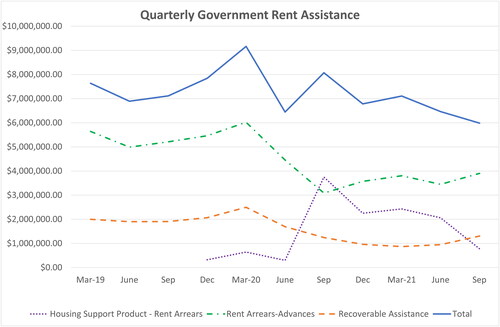

With sporadic and uncertain generosity from landlords, the onus was on tenants to navigate rent assistance. The primary source of support was a loan from MSD. The amount of recoverable rent assistance paid during the crisis is shown in the graph in .

shows Housing Support PaymentsFootnote6 (HSP) rose from $644,591 (489 grants) in March 2020 to $3,746,299 (2568 grants) in the September quarter of 2020. Figure 1 shows there was a reduction in the amount paid out under Rent Arrears - Advances in September 2020, and conversely, a rise in the amount paid under HSP grants. This suggests that tenants experienced hardship after the lockdown that was addressed by the HSP payment. In total, just over $9 million dollars was paid in loans in the March 2020 quarter—with $6 million of this attributable to advances in the main benefit. This was a peak prior to the lockdown and the full impacts of COVID-19. In June 2020 it had dropped to $6,442,882 before a second peak of $8 million in September 2020, well under the allocated budget.

Figure 1. Recoverable rent assistance loans. Data source: MSD, Citation2021a.

Importantly, rent arrears payments were taken on as debt. In 2008, half of beneficiaries were in debt to MSD. By 2021 this had risen to 65% with a median of $1,618 owed in 2021 compared to $1,342 in 2019 (MSD, Citation2021b). At face value these figures set out the unaffordability of rental housing for low-income renters, and the considerable cumulative debt that households took up to keep their homes. It also illustrates the compounding effects of the pandemic on populations already experiencing hardship and rising debt.

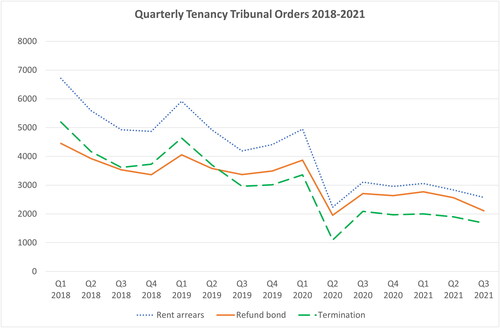

Despite expectations of an increase in disputes (Office of the Minister of Housing, Citation2020), rates of tenancy terminations dropped significantly at the advent of the lockdown, part of a downward trend that can be seen in application numbers since 2018 in (MBIE., Citation2021), suggesting landlords, who make up the majority of applicants, are using other methods as a recourse for arrears and dispute.

Figure 2. Tenancy tribunal orders by quarter. Data source: MBIE., Citation2021.

Closed bonds, which mark the end of a tenancy, also dropped off during the lockdown period of March 2020 as people were restricted from moving to a new house or ending a tenancy. These recovered quite quickly to pre-COVID levels with just a 3% increase in September 2020 compared to 2019, an indication that rates of movement were close to normal.

Discussion

We identify two obstacles to compassion arising in response to renters during the pandemic; tenant reliance on individual acts of kindness which compounded inequities in power; and the unreliability of compassion as a motivation of Government action, when confronted with market considerations. We describe and discuss these here, before examining the implications for the value of a politics of compassion to the PRS.

Rebecca Solnit, author of Paradise made in Hell, a study of behaviour in crisis, observed that in a disaster, ‘most people are altruistic, urgently engaged in caring for themselves and those around them, strangers and neighbours as well as friends and loved ones’ (Solnit, Citation2009, 2). This was a crisis affecting everyone, thus engendering shared feelings of compassion. Political rhetoric served to reinforce the appropriateness of kind action, where ‘a shared sense of identity or purpose can be encouraged by addressing the public in collective terms and by urging ‘us’ to act for the common good’ (Bavel et al., Citation2020, p. 460). This response reflects the inherent human capacity for kindness, a pull that can transcend some of the power of the market at times; examples of a moral influence on the operation of markets (Smith, Citation2005), which placed value on the wellbeing of tenants.

However, where kindness was shown by landlords, it was individualised, variable, temporary, and subject to the general satisfaction of long-term profit. Kindness, while effective as a basis for the public health response during the pandemic, manifests, in part, as a product of landlord power, when used to guide individualised action in the PRS.

This power is demonstrated in the way that directives to be kind centred the power of the landlord and diminished the agency of tenants, compounding existing inequalities between landlords and tenants. Tenants could not expect kindness or fight for it, they could only experience it; ‘although compassion does presuppose that the person does not deserve the (full measure of) the hardship he or she endures, it does not entail that the person has a right or a just claim to relief’ (Nussbaum, Citation1996, 28). In addition, the power dynamic of the private rental market means asking a landlord for help, even for necessary repairs, is fraught (Chisholm et al., Citation2020). If asked, a landlord could decline, potentially creating discomfort for the tenant, as they also held the power to decide on the continuation of the tenancy, or at least the tone of the relationship associated with the tenant’s time in their home.

Despite asking private landlords to act with compassion, the Government’s own actions fell short of ensuring this. Aotearoa, like similar Anglophone countries (Soaita, Citation2021), was able to largely avoid a feared rise in evictions. At the same time, emergency food grants soared (Neuwelt-Kearns, Citation2020), and debt levels increased, potentially reflecting the adage ‘the rent eats first’ (Desmond, Citation2016, 302). Certainly, as in other nations, the cost of pandemic policies was a widening of inequalities (Waldron, Citation2022). In 2020, struggling private rental households took on around $30 million dollars in rental assistance debt in attempts to stay housed (MSD, Citation2021a), while businesses accrued a ‘$13 billion lift in corporate wealth, […] roughly equivalent to the cost of the wage subsidy programme’ (Johnson, Citation2021, p. 78). Coupled with an unregulated property market and ensuing rises in house prices and rents, the pandemic response heralded the ‘biggest transfer of wealth from current and future renters to asset owners, in the history of NZ’ (Hickey, Citation2022).

Thus, while a political rhetoric of kindness was unifying in a time of crisis, it did not ensure PRS landlord actions, or government policies, were all fair or kind, and instead, further entrenched inequities. While the decision to make support to renters a loan rather than a grant may seem trivial, and advice for landlords ‘to be kind’ innocuous, they had direct impacts on outcomes for tenants, and provide examples of the obstacles to a politics of compassion.

A/NZ is an interesting case study because of the open willingness of the Government to create a system more conducive to renting, and the intention to act with compassion. Arguably, the current Government has done more for renters than any other in NZ. There have been improvements in housing standards, the removal of no-cause evictions, limitations on rent increases, and a large public housing building programme (Labour Party, Citation2021). Policies intended to deter speculation include an extension of a capital gains tax on profits of rental properties sold prior to 10 years and the removal of interest deductions on mortgage payments (Robertson et al., Citation2021).

However, despite these modifications, outcomes for renters have not, overall, materially improved. Rents are at a record high. Gains have been made on housing standards, yet these remain incomplete and unenforced. There was also an incongruence between intentions to support tenants, and the actions of Government towards PRS renters during the pandemic. Emphasis in Cabinet papers outlining COVID-19 decision making sought to ensure the rental market ‘recalibrated effectively’ ‘allowing rental markets to find a ‘new normal’ ‘without too much of a distortionary effect from government support’ (Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee, Citation2020b)—perhaps in fear of repeating the scale of the Accommodation Supplement, a $34.9 million weekly grant paid indirectly to landlords for unaffordable rents (MHUD, Citation2020b). It was intended that people stay in their homes, in the short term, to prevent transmission of COVID-19, without upsetting the market. Tenants were still able to be evicted once they were 60 days in arrears, rather than 21—not a moratorium, but a respite, in recognition of the ‘significant change to current landlord property rights’ (MHUD, Citation2020a). The overall Government approach suggests the rental market was afforded a sense of reverence, ‘invested [….] with a foundationalism [….] and an essentialism that puts it beyond political or practical control’ (Smith, Citation2005, p. 4).

Given these obstacles, what are the possibilities of a politics of compassion for the PRS? While there are problematic components in the politics of compassion as realised in Aotearoa (Asafo, Citation2021), we look to its potential (Willis & Kavka, Citation2021). The variability of landlord action during the pandemic needed to be more clearly guided through regulation—kindness requires some manifestation in law to have effect (Nussbaum, Citation1996). Arendt argues that once generalised within public administration ‘compassion’ is expressed as pity: ‘to be sorry without being touched in the flesh’ (Arendt, Citation1990). It cannot be generated or manifested beyond individual interaction, without imagination and experience of individual suffering. However, we argue the main problem is not the risk of compassion turning to pity (Arendt, Citation2006), but a lack of connection enabling compassion and solidarity, and an imbalance of power between those who can choose how to act—landlords, politicians, and administrators—and the tenants they act for. This is compounded by the dominance of an individualised market ethic appearing at odds with an ethic of care and compassion (Smith, Citation2005).

Our observation of compassionate responses by landlords during the pandemic suggests the challenge for a politics of compassion is to expose society to the everyday crisis of inequities in housing. Practical strategies, like the planned inclusion of the history of colonisation (intimately tied to housing outcomes in Aotearoa) in our education system (Johnson, Citation2021), opportunities for connection within communities, and in the facilitation of tenant rights into the public realm through tenant unions, advocacy, journalism, and academic research will enable an increase in understanding and opportunities for empathy from those in power—the ‘bridge’ to socially just action (Nussbaum, Citation1996). A politics of compassion for the PRS would centre the ‘use value of housing’ (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016) and the experiences of tenants—those who live precariously and are excluded from the cushioning multi-facetted benefits of (multiple) homeownership. This cannot be a politics ‘for’ instead of ‘with’ (Weber, Citation2018)—it must be based on agency, dignity and the sharing of power; compassion as solidarity, rather than pity (Arendt, Citation2006).

Furthermore, a politics of compassion, without attention to questions of power, rights, and robust legal regulation, risks further entrenching inequity, hierarchy, and pity. Consciousness of power is essential—while compassion has the potential to enable solidarity, it is also focussed on the compassionate, rather than those who ‘suffer’, potentially ‘othering’ those oppressed by the system (Arendt, Citation2006); it is directed at those who have power (Asafo, Citation2021). In action, it necessitates a particular response to the activism of the ‘oppressed’, and to evidence of injustice—it creates reception and space for the claiming of rights and social justice, and the manifestation of this in law, to redress the unreliability of compassion from those with power.

A compassionate rental sector, then, requires a rebalancing of tenant/landlord power through evidence-based and independently enforced housing standards, the recasting of rent arrears as a result of inequity and structural issues, rather than delinquency (Hunter & Nixon, Citation1999), long-term security of tenure, greater property rights to tenants to modify a house as their own, indiscriminate selection of tenants, and the use of financial regulation to rein in over-investment in housing for capital gain. It may be, that the realisation of a compassionate PRS is incompatible with the profit motivations of small-time landlords, and that the delivery of housing, in a compassionate society, is best done through other tenure models—like public and institutionally owned housing. As we engage in discussions on the just delivery of housing, encouragement and opportunity for compassion and empathy, embedded in civil society and across our institutions, will enable greater receptivity to the readjustment of policies and markets to enable a right to home for all, including from those who hold that power now.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Original and Indigenous name of ‘New Zealand’ used widely.

2 Traditional meeting place with contemporary importance to Māori.

3 Kindness, care.

4 Ability to issue no cause termination notice was removed from the Residential Tenancies Act (1986) in 2021.

5 (schedule 5, provisions relating to outbreak of COVID-19 (4(3)b) https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1986/0120/latest/LMS328971.html

6 PRS HSP used here are recoverable loans.

References

- Adkins, L., Konings, M., & Cooper, M. (2020). The asset economy: Property ownership and the new logic of inequality. Polity Press.

- Amore, K., Viggers, H., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2020). Severe housing deprivation in Aotearoa New Zealand, 2018. University of Otago. https://www.healthyhousing.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Severe-housing-deprivation-in-Aotearoa-2001-2013-1.pdf

- Ardern, J. (2017). Speech from the throne. Beehive.govt.nz. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-throne-2017.

- Ardern, J. (2020). Prime Minister: COVID-19 alert level increased, 23 March 2020. Beehive.govt.nz. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/prime-minister-COVID-19-alert-level-increased.

- Arendt, H. (1990). Politics and compassion. Quadrant, 34(12), 78–80.

- Arendt, H. (2006). On revolution. Penguin Books.

- Asafo, D. (2021). Kindness’ as violence in the settler-colonial state of New Zealand. Knowledge Cultures, 9(3), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc9320213

- Baum, F., Freeman, T., Musolino, C., Abramovitz, M., De Ceukelaire, W., Flavel, J., Friel, S., Giugliani, C., Howden-Chapman, P., Huong, N. T., London, L., McKee, M., Popay, J., Serag, H., & Villar, E. (2021). Explaining COVID-19 performance: What factors might predict national responses? BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n91. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n91.

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.

- Bierre, S., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2020). Telling stories: The role of narratives in rental housing policy change in New Zealand. Housing Studies, 35(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1363379.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Byrne, M. (2020). Generation rent and the financialization of housing: A comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain. Housing Studies, 35(4), 743–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1632813

- Byrne, M., & McArdle, R. (2022). Secure occupancy, power and the landlord-tenant relation: A qualitative exploration of the Irish private rental sector. Housing Studies, 37(1), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1803801

- Byrne, M., & Sassi, J. (2022). Making and unmaking home in the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative research study of the experience of private rental tenants in Ireland. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2037176

- Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee (2020a). Expanding access and level of rent arrears assistance temporarily to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on housing outcomes, June 2 2020. https://covid19.govt.nz/assets/resources/proactive-release-2020-july/H4-Paper-and-Minute-Expanding-Access-to-Rent-Arrears-Assistance.pdf 15 December 2021.

- Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee. (2020b). Expanding access to rent arrears assistance Swc-20-Min-0052, 27 May 2020. https://covid19.govt.nz/assets/resources/proactive-release-2020-july/H4-Paper-and-Minute-Expanding-Access-to-Rent-Arrears-Assistance.pdf.

- Chisholm, E., Bierre, S., Davies, C., & Howden‐Chapman, P. (2022). ‘That House Was a Home’: Qualitative evidence from New Zealand on the connections between rental housing eviction and poor health outcomes. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 33(3), 861–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.526

- Chisholm, E., Howden-Chapman, P., & Fougere, G. (2020). Tenants’ responses to substandard housing: Hidden and invisible power and the failure of rental housing regulation. Housing, Theory, and Society, 37(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1538019

- Coughlan, T. (2020). Coronavirus: Jacinda Ardern wants names of landlords flouting new rules. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120603924/coronavirus-jacinda-ardern-wants-names-of-landlords-flouting-new-rules.15 December 2021.

- Davies, C., Timu-Parata, C., Stairmand, J., Robson, B., Kvalsvig, A., Lum, D., & Signal, V. (2022). A Kia Ora, a wave and a smile: An urban Marae-led response to COVID-19, a case study in Manaakitanga. International Journal for Equity in Health, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01667-8

- Desmond, M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American City. Crown Books.

- Eaqub, S., & Eaqub, S. (2015). Generation rent. Bridget Williams Books.

- Fletcher, M., Prickett, K. C., & Chapple, S. (2022). Immediate employment and income impacts of COVID-19 in New Zealand: Evidence from a survey conducted during the alert level 4 lockdown. New Zealand Economic Papers, 56(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00779954.2020.1870537

- Frischknecht, D. (2020). Evidence brief: The impacts of COVID-19 on one-off hardship assistance. Ministry of Social Development, Wellington. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/COVID-19/the-impacts-of-COVID-19-on-one-off-hardship-assistance.pdf

- Harris, M. (2017). The New Zealand project. Bridget Williams Books.

- Hickey, B. (2022). Covid’s big winners and losers revealed. In Bernard Hickey (Ed.), The Kākā. thekaka.substack.com.

- Houkamau, C. A., & Sibley, C. G. (2015). Looking Māori predicts decreased rates of home ownership: Institutional racism in housing based on perceived appearance. PloS One, 10(3), e0118540. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118540.

- Howden-Chapman, P. (2015). Home truths: Confronting New Zealand’s housing crisis. BWB Text.

- HUD. (2021). Public housing quarterly report—December 2020. Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/Community-and-Public-Housing/Follow-our-progress/Quarterly-Reports-2020/Public-Housing-Quarterly-Report-December-2020.pdf 15 December 2021.

- Hunter, C., & Nixon, J. (1999). The discourse of housing debt: The social construction of landlords, lenders, borrowers and tenants. Housing, Theory, and Society, 16(4), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036099950149893

- Jackson, M. (2020). Where to next? Decolonisation and the stories of the land. In R. Kiddle (Ed.) Imagining Decolonisation (133–155). Bridget Williams.

- Jacobs, K., & Manzi, T. (2000). Evaluating the social constructionist paradigm in housing research. Housing, Theory and Society, 17(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/140360900750044764

- Jamieson, T. (2020). “Go Hard, Go Early”: Preliminary lessons from New Zealand’s response to COVID-19. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941721

- Johnson, A. (2021). The politics and policies of kindness in Aotearoa New Zealand. Knowledge Cultures, 9(3), 76–89. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc9320215

- Jowett, A. (2015). A case for using online discussion forums in critical psychological research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(3), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2015.1008906

- Key, J. (2011). Speech from the throne, 21 December 2011. Beehive.govt.nz. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/speech/speech-throne-1.

- Labour Party. (2021). How labour is backing renters. Labour Party of New Zealand, Accessed 12 December 2021. https://www.labour.org.nz/news-how-labour-is-backing-renters

- Madden, D. J., & Marcuse, P. (2016). Defense of housing: The politics of crisis (Peter Marcuse, Ed.). Verso.

- Malpezzi, S. (2022). Housing affordability and responses during times of stress: A preliminary look during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contemporary Economic Policy. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12563

- Martin, C., Sisson, A., & Thompson, S. (2021). Reluctant regulators? Rent regulation in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1983246

- Matthew, J. N. (2007). Totalized compassion: The (im)possibilities for acting out of compassion in the Rhetoric of Hannah Arendt. JAC: A Journal of Composition Theory, 27(1/2), 105–133.

- Mazey, S., & Richardson, J. (2020). Lesson-drawing from New Zealand and COVID-19: The need for anticipatory policy making. The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12893

- MBIE. (2021). Official Information Act (1982) request, 18 November 2021. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

- McGuire, D., Cunningham, J. E. A., Reynolds, K., & Matthews-Smith, G. (2020). Beating the virus: An examination of the crisis communication approach taken by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern during the COVID-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1779543

- McKee, K., Soaita, A. M., & Hoolachan, J. (2020). Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1468–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1676400.

- MHUD. (2020a). COVID-19: Residential Tenancies Act amendments, 24 March 2020.

- MHUD. (2020b). Public housing quarterly report—June 2020. https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/Community-and-Public-Housing/Follow-our-progress/Quarterly-Reports-2020/Housing-Quarterly-Report-June-2020.pdf

- Molyneux, V., & Lynch, J. (2020). Coronavirus: Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern blasts commercial rent hikes amid COVID-19 lockdown, 15 April 2020. Newshub. https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2020/04/coronavirus-prime-minister-jacinda-ardern-blasts-commercial-rent-hikes-amid-COVID-19-lockdown.html.15 December 2021.

- Morris, A., Hulse, K., & Pawson, H. (2021). Private renting and rental stress. In Alan Morris, Kath Hulse & Hal Pawson (Eds.), The private rental sector in Australia: Living with uncertainty (107–127). Springer Singapore.

- MSD. (2021a). Official Information Act (1982) request, 12 October 2021. Ministry of Social Development.

- MSD. (2021b). Official Information Act (1982) request, 23 November 2021. Ministry of Social Development.

- Murphy, L. (2020). Neoliberal social housing policies, market logics and social rented housing reforms in New Zealand. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(2), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1638134

- Neuwelt-Kearns, C. (2020). Aotearoa, land of the long wide bare cupboard. Child Poverty Action Group, Auckland. https://www.cpag.org.nz/campaigns/the-latest-aotearoa-land-of-the-long-wide/

- Nussbaum, M. (1996). Compassion: The basic social emotion. Social Philosophy and Policy, 13(1), 27–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265052500001515

- Nussbaum, M. (2013). Political emotions: Why love matters for justice. Harvard University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). Upheavals of thought: The intelligence of emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Office of the Minister of Housing. (2020). Cabinet paper: Immediate housing response to Covid 19. https://www.hud.govt.nz/assets/News-and-Resources/Proactive-Releases/Cabinet-Paper-Immediate-Housing-Response-to-COVID-19.pdf.

- Parsell, C., Clarke, A., & Kuskoff, E. (2020). Understanding responses to homelessness during COVID-19: An examination of Australia. Housing Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1829564

- Paul, J., McArthur, J., King, J., & Harris, M. (2020). Transformative housing policy for Aotearoa New Zealand: A briefing note on addressing the housing crisis. University of Auckland.

- Pawson, H., Martin, C., Thompson, S., Aminpour, F., Gibb, K., & Foye, C. (2022). COVID-19: Housing market impacts and housing policy responses—An International Review. 16 ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership, Sydney

- Porter, E. (2006). Can politics practice compassion? Hypatia, 21(4), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2006.tb01130.x

- Power, E. R. (2019). Assembling the capacity to care: caring‐with precarious housing. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 44(4), 763–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12306

- Power, E. R., & Bergan, T. L. (2019). Care and resistance to neoliberal reform in social housing. Housing, Theory, and Society, 36(4), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1515112

- REINZ. (2021). Wellington house prices increase by 39% in 12 months. https://wellington.scoop.co.nz/?p=138309.15 December 2021.

- Renters United. (2020). Renting under lockdown. Renters United, Wellington. https://www.rentersunited.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/renting-under-lockdown-report-final.pdf 15 December 2021.

- Robertson, G., Woods, M., & Parker, D. (2021). Details of interest deductibility rules released, 28 September 2021. Beehive.govt.nz, Accessed 12 December 2021. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/details-interest-deductibility-rules-released 15 December 2021.

- Rogers, D., & Power, E. R. (2021). The global pandemic is accelerating housing crises. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(3), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1957564

- Rosenberg, B. (2020). Support for workers in the COVID-19 emergency: What can we learn? Policy Quarterly, 16(3), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v16i3.6559

- Rosenthal, D. M., Ucci, M., Heys, M., Hayward, A., & Lakhanpaul, M. (2020). Impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable children in temporary accommodation in the UK. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), e241–e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30080-3

- Shadmi, E., Chen, Y., Dourado, I., Faran-Perach, I., Furler, J., Hangoma, P., Hanvoravongchai, P., Obando, C., Petrosyan, V., Rao, K. D., Ruano, A. L., Shi, L., de Souza, L. E., Spitzer-Shohat, S., Sturgiss, E., Suphanchaimat, R., Uribe, M. V., & Willems, S. (2020). Health equity and COVID-19: Global perspectives. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z

- Shaw, E. K. (2020). The use of online discussion forums and communities for health research. Family Practice, 37(4), 574–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmaa008.

- Skilling, P. (2018). Why can’t we get what we want? Inequality and the early discursive practice of the sixth labour government. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 13(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2018.1486328

- Smith, S. J. (2005). States, markets and an ethic of care. Political Geography, 24(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.10.006

- Soaita, A. M. (2021). Renting during the COVID-19 pandemic in Great Britain: The experiences of private tenants. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, United Kingdom. https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Renting-during-the-COVID-19-pandemic-in-Great-Britain-final.pdf

- Solnit, R. (2009). A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. Penguin Books.

- Statistics NZ. (2020). Unemployment rate hits 5.3 percent due to COVID-19. Statistics New Zealand.

- Stats NZ. (2020). Housing in Aotearoa. Statistics New Zealand, Wellington. www.stats.govt.nz 15 December 2021.

- Tenancy Services. (2021). Guidance for rent negotiation discussions. Tenancy Services, Tenancy.govt.nz Accessed 27 October 2021. https://www.tenancy.govt.nz/assets/_generated_pdfs/guidance-for-discussion-1376-en_NZ.pdf.

- Ure, M., & Frost, M. (2014). Introduction. In Michael Ure & Mervyn Frost (Eds.), The Politics of Compassion (1–18). Routledge.

- van Leeuwen, T. (2018). Moral evaluation in critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(2), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1427120

- Versey, H. S. (2021). The impending eviction cliff: Housing insecurity during COVID-19. American Journal of Public Health, 111(8), 1423–1427. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306353.

- Waldron, R. (2022). Experiencing housing precarity in the private rental sector during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The case of Ireland. Housing Studies, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2032613

- Weber, A.-K. (2018). The pitfalls of “Love and Kindness”: On the challenges to compassion/pity as a political emotion. Politics and Governance, 6(4), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i4.1393

- White, V. W., M Jones, C. V. J., & Chun, S. (2017). Branz 2015 house condition survey: Comparison of house condition by tenure. BRANZ Ltd.

- Whitebrook, M. (2002). Compassion as a political virtue. Political Studies, 50(3), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00383

- Whitebrook, M. (2014). Love and anger and political virtues. In Mervyn & Frost Michael Ure (Eds.), Politics of Compassion (21–36). Routledge.

- Willis, E., & Kavka, A. (2021). Editorial: The politics and practices of kindness. Knowledge Cultures, 9(3), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.22381/kc9320211.

- Wilson, S. (2020). Pandemic leadership: Lessons from New Zealand’s approach to COVID-19. Leadership (London, England), 16(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715020929151

- Witten, K., Wall, M., Carroll, P., Telfar-Barnard, L., Asiasiga, L., Graydon-Guy, T., Huckle, T., & Scott, K. (2017). The New Zealand rental sector. Massey University SHORE and Whariki Research Centre, University of Otago and BRANZ.

- Wong, J., & Wong, N. (2021). The economics and accounting for COVID-19 wage subsidy and other government grants. Pacific Accounting Review, 33(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-10-2020-0189