ABSTRACT

Following a particular interest in memories and stories of exile and their representation in artistic photography, I draw critical attention to the notion of diasporic aesthetics. I ask why visual and performative strategies of storytelling matter as fundamental methods not only of self-representation, but also of transcultural expressions of “belonging” across various cultural and geographical borders. Reflecting on Parastou Forouhar, an Iranian artist living in exile in Germany, and her photographic series Das Grass ist Grün, der Himmel ist Blau, und Sie ist Schwarz [The Grass is Green, the Sky is Blue, and She is Black] (2017), I argue that artistic photography constitutes a social practice that carries the potential to create relations of solidarity with other migratory groups. These groups may share similar diasporic aesthetics, or be familiar with experiences of migration and exile or discrimination and exclusion. Moreover, within the scope of photography and migration and its particular expression and performances of belonging, the practice produces a creative space where cultural differences and boundaries may generate shared forms of identification and contestation that transcend national and ethnic identities. After arguing for photography as a medium that expresses the multiple notions and struggles of the ongoing processes through which “belonging becomes”, conclude that photography can generate a sensorium, a space that provides possibilities of critical transcultural engagement and encounters in post-migration societies.

Introduction

The history of Iranian migration to Europe reveals a transnational, cosmopolitan genealogy of Iranian diaspora and exiles. Whereas the term transnational describes more clearly the way in which, as Hamid Dabashi writes, “Iranians at home and abroad establish a global cultural identity tinged by the nostalgia and loss implied in the term diaspora”,Footnote1 the term diaspora may also carry a specific political valence. Accordingly, and as formulated by Babak Elahi and Peris M. Karim, such “references to a post-revolutionary disillusionment help identify the term of the Iranian “diaspora” then very specifically as the Iranian Left, who “staged” the 1979 revolution that they subsequently lost to the stage directions of Islamist politics” (Elahi and Karim Citation2011). This distinction between transnationalism and diaspora is helpful, in that it helps us to define the nuances of the Iranian diaspora and its various internal differences within the overarching definition of diaspora as a category. Such differences are marked by aspects such as generation and gender, forms of migration, and political moments within Iran as well as the host societies. A myth of the homeland and the diverse responses to it as well as to the host nation are essentially constitutive of the character of the Iranian diaspora. However, a diasporic group must not be understood as a primarily discrete entity nor according to its relationship to constructions of place (Axel Citation2002), but rather as formed by “a series of contradictory convergences of peoples, ideas, and even cultural orientations” (Quayson and Daswani Citation2013). Experiences of spatiality and the relation to a diversity of spaces and places form feelings of belonging to a diasporic group. Moreover, experiences and memories of displacement, departure, arrival, settlement and dwelling are consequently part of such formation processes. In other words, this is never a clear and fixed personal condition, and so it is pertinent to ask how and when individuals express their belonging and identification in a migratory setting. In such an investigation, the concept of a transnational aesthetics of diaspora as coined by Pnina Werbner and Matti Fumanti proves insightful (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013; Citation2014). Arguing for “a multi-sensual, ambient, ontological aesthetics, embedded in sociality and actively produced by participants”, the authors underline that much of this is “invisible to outsiders, oriented to audiences elsewhere or members of their encapsulated local communities” (171). What is important for their argumentation is that the idea of aesthetics as a form of distinction is employed by migrating people and groups, and is not reserved for any dominant group (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013). Moreover, and as the authors explain, “[t]hrough performance, migrant groups, diasporans and artists in exile […] claim ownership to the countries they choose to live in, whether temporarily or permanently, by creating liminal aesthetic spaces that are theirs, and which inevitably in the long run enrich the cultures of their new homes and adopted nations’ identities” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 171). Werbner and Fumanti suggest a diasporic aesthetic approach that goes beyond former post-colonial discussions and understandings of diasporas as productive of hybrid cultures and third spaces. But what kinds of new perspectives and critical questions does this bring about in the field of diaspora studies where far too often a generalising idea of “diaspora” is applied? Do notions of ownership or distinction reopen discussions on the articulation of migration and its cross-cultural social impact on originating and host-societies from the fields of literature, film and the visual arts?

Werbner and Fumanti argue that certain emblematic milieus may be imported and (re)created as a result of a “dialogical forging” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013) rather then stemming from nostalgia for the homeland alone. But what significance does this have for the analysis of works of art and photography and the role they may play within broader processes of social transformation and institutional change in migratory contexts? Is it really possible to talk about “shared canons of taste among diasporic producers and consumers who collectively define what makes for social distinction […]”(150)? When looking at artists in exile and migration is it not necessary to consider the different institutional contexts, the much wider audiences artists they reach with their art, or their often highly transcultural and transnational personal and professional surroundings rather than simply following preconceived notions of a transnational and imagined diasporic community (Axel Citation2002)? A collective definition of taste as marking social distinction may hint towards a diasporic imagery that “indicates a precise and powerful kind of identification that is very real […] [and that] shifts the emphasis to temporality and corporeality […]” away from the account of place of origin (423). However, would this not also imply that such imagery is generated and informed by a multiplicity of temporalities, localities, traditions, identities, and subjectivities? If we understand that art reaches wider publics beyond a diasporic context of belonging, we may then look at how social distinctions are generated alongside multiple and contested imageries, not only diasporic once, as they encourage a multiplicity of belongings rather than identification with a single diasporic community. Taking a particular interest in experiences of memories, stories of exile (Sullivan Citation2001) and their representation in artistic photography, this article draws critical attention to the notion of diasporic aesthetics. Instead of searching for signs of shared taste, a diasporic imaginary and a cultural and spatial bounded sense of belonging, it opens these categories up to ask whether visual and performative strategies in artistic photography matter, not only as fundamental strategies of self-representation but also as transcultural expressions of “belonging” across various cultural and geographical borders. In analysing the photographic series Das Grass ist Grün, der Himmel ist Blau, und Sie ist Schwarz [The Grass is Green, the Sky is Blue, and She is Black]Footnote2 by Parastou Forouhar, an Iranian artist living in exile in Germany, I will demonstrate that employed aesthetics of photography such as performative storytelling function as identifiers for a variety of transnational/transcultural migration contexts instead of within a single diasporic one. I will argue that Forouhar’s work creates a liminal aesthetic space that enriches German and European cultures as a site of transcultural entanglement and negotiation beyond national identification. Her work thus constitutes a prime example of the production of senses of belonging in postmigrationFootnote3 context which is understood as a “non-binary description of the movement, exchange and settlement of people and ideas across both imaginative and material boundaries”Footnote4 and which sheds light on migration as constitutive and permanent condition in societal reality instead of a completed process (Hill and Yildiz Citation2018).

Using postmigration as a starting point, I will continue to argue that artistic photography is a social practice that carries a specific potential to create relations of solidarity with other migratory groups who share similar diasporic aesthetics such as a veil or hijab, or who are familiar with experiences of migration and exile or discrimination and exclusion. Moreover, within the scope of photography and migration and its particular expression and performances of belonging, the creative space that artistic photography produces in institutional settings such as museums, galleries and exhibitions turns into a site where cultural differences and boundaries get transformed and produce shared forms of identification that transcend national/ethnic identities. With regards to rapid technological advancement, it seems valid to argue for photography as a medium that can express the multiple notions and struggles of ongoing processes when “belonging becomes” (Meskimmon Citation2017, 32). Since it also engages members outside specific diasporic communities, the main question here is as to the potential roles of visual practices, particularly photography. Considering artistic photography as a fundamentally transnational and transcultural social practice,Footnote5 rather than a limiting mono-cultural diasporic one positions photographers and artists as denizens in postmigration world-making processes. As Marsha Meskimmon argues, the denizen, in contrast to the citizen, comprehends “the specificity of multiple forms of sociability, the dynamic processes of intersectional identifications and the affective forms of belonging that enable worlds and subjects to find a voice and a place” (Meskimmon Citation2017, 33). Thus, photography by exiled artists provides a central transcultural medium with a specific mediative and translatory potential (Bublatzky Citation2018, 118) that transgresses all kinds of local, regional and transnational borders and enforces processes of negotiation and contestation. In this sense, a diasporic aesthetics approach appears almost limitating and encapsulating when imposed upon artists in migrations contexts such as Parastou Forouhar as a “being in the world”, or as a “presence in the diaspora” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 156).

Even more importantly, and within artistic photography’s function as a transcultural medium for remembering and communicating, this seems to be essential in generating participatory sensorial abilities and empathy, as well as in drawing lines towards imagined others. In this sense, I shall demonstrate that photography is a constituent part of a transnational if not a global visual regimeFootnote6 of migration and post-migration.Footnote7 If photography in general actively shapes and determines visual histories of diasporas, than Parastou Forouhar’s photographic work is discussed here as a series of empirical insights into the perceptions of such individuals and the complexity of their lifeworlds as shaped by migration, diaspora and exile, whilst representations of “becoming” are viewed as a process of belonging or, the other way around, representations of “belonging” can also be seen as process of “becoming”. Here, Iranian-born artist Parastou Forouhar represents an interesting protagonist. Forouhar belongs to the so-called Burnt Generation, a social group that encompasses Iranians born between the early 1960 s and the early 1980 s. This expression refers in particular to people who lived most of their lives in an environment dominated by war and religious dogmatism in Iran (Grassian Citation2012, 8). Many members of this generation, including many artists, intellectuals, writers and film makers fled from the repressive regime as a result of the cruel events of the 1979 revolution and the declaration of Iran as an Islamic theocracy. Resettling across the world, these people formed multiple groups of diasporic communities, in particular in the USA, France, Germany and England, thus forming a highly diverse global Iranian diaspora.

Parastou Forouhar left her country to study art at the University of Art and Design (HFG) in Offenbach, Germany in 1991. In 1998, however, her parents were brutally assassinated in Tehran, likely in connection with their political and secularist activism. Forouhar became a permanent exile and has since then dedicated her artistic and political activities to issues such as freedom of speech, human rights and the fight for clarification around these political murders. The following discussion will first introduce the artist Parastou Forouhar and a selection of her works before discussing the fabrication of identity and the reconstruction of migration and memory (Bublatzky Citation2019). These concepts will then be analysed through the lens of a transnational aesthetics of diaspora. I shall then demonstrate the delimiting problematics of such diasporic aesthetics, arguing that this implies an isolated condition of identification and self-expression by members of a certain diasporic community whilst ignoring outsiders and members of perceived dominant cultural groups or other diasporic groups.

Parastou Forouhar

In 1998, the politically motivated murder of her parents Parvaneh and Dariush Forouhar forced the artist Parastou Forouhar into a German exile. Her exploration of different techniques such as installation, animation, digital drawing and photography is, as she herself has stated, a way to respond to the politics that have been shaping and defining her life and sense of belonging both in Iran and in Germany ever since that day.Footnote8 Moreover, and as Forouhar writes in one of her books,

“the murder of my parents has strengthened my strangeness in Germany and gradually created a trench of loneliness that stretches along my deep bond with this society. I tell stories that often go beyond the framework of local realities and everyday life. But I continue telling them in the hope that they will break through the barriers of foreignness and become at home here”.Footnote9

In these visual stories, Forouhar often employs recurrent elements and contested signs of public life such as written language or garments that help to identify a migrated “other” in public discourses. One example is the veil or hijab as a signifier for Islam and specific religious and social-practices that represent a central element of socio-political contestation and conflict in many Islamic and European countries. The recent ban on full-face coverings—including burkas and niqabs—in public spaces in Denmark (2018) is just one of many examples of such public controversies. The act of wearing a hijab can always tell different stories, and women may wear it for a myriad of (sometimes intersecting) cultural, religious, traditional and personal reasons. However, it also generates different and often stereotyped images and fantasies, and is attributed changing meanings and messages by the outsiders’, often non-Muslim, world.

In several of her works, Parastou Forouhar employs the black chador (a full-body veil) alongside performative photography with the intent to challenge and disrupt stereotypical notions of the “self” and the “other”. In her photo series Swanrider (2004), for example, the artist enacts an ironic form of play in which a woman (the artist herself) dressed in a black chador rides on a huge paddleboat in the form of a white swan. The contrast between black and white is overpowering and reminiscent of fairy tales structured by such opposites as good and evil. There are also further echoes of the story of the ugly duckling becoming a beautiful swan: a metaphor for the outsider who becomes the radiant focus of attention. Such references to miraculous transformations are an ironic take on the role of the woman in the dark chador, since they contradict stereotypical perception of Muslim women in the public space. Similarly, Forouhar’s work Friday (2003) shows a detail of a beautifully ornamented black chador and part of a male hand holding the cloth. In this work, tension emerges from the contrast between concealment and a controlled visible. The artistic performance of showing limited fragments of a male body speak of the gender control and politics that oppress women in their everyday life. The title of the piece refers to the Friday prayers central to Moslem religions on their day of rest, prayers and sermons, and morality and order.

In a talk in 2004 called Veiled, Unveiled, Parastou Forouhar remembered the moment that she entered Tehran University in 1984 to study art, five years after the Revolution and at a time when the fundamentalists had just begun to consolidate their power. In post-revolutionary Iran, Islamisation also meant enforcing the strict separation of men and women in public spaces, gender-specific dress codes, and that education predominantly revolved around subjects such as Islamic religion, philosophy or history at university. Forouhar describes the atmosphere of that time as threatening and depressing. Seemingly influenced by this experience, the artist displaces the cultural symbolism of the chador in her practice, relocating it into various different settings. As Friday demonstrates, she links gender politics with cultures of wearing the chador, thus challenging its meaning and cultural attributes by communicating it to various audiences and in different cultural, institutional or exhibitionary settings (Forouhar Citation2004). In many of Forouhar’s works we can observe playful, humorous, even ironic gestures towards themes of cultural difference, attribution and identification of the self and the foreign other. Alexandra Karentzos has argued that the artist uses irony and contradiction to create an estrangement in a manner which is twofold: by performing the stranger herself, she plays with the viewer’s conventional perception and, at least upon first glance, endorses certain stereotypes of Islam such as the role of women and the chador. At same time, the manner of performance, i.e. how the artist positions herself in certain settings, often does not substantiate but rather challenges such stereotypes. In this way, Forouhar alienates not only those who practice strict religious conventions, but also those who might typecast Islam as limiting. But the artist also estranges herself too because she does not create a certain Iranian identity. Instead she produces a space where such attributions as “Islam”, “Iranian” or “female Muslim” might take place, and are contested and negotiated (Karentzos Citation2006, 138). This also echoes what the artist explained to me in one of our conversations; she talked about being situated in-between, neither here nor there at home, and told me that the act of arriving as an artist in Germany was what made her Iranian in the first place.Footnote10 I found this reminiscent of Homi Bhabha and his discussion of third space, or of Hamid Naficy’s striking description of Iranian film-makers and artists’ situation as living in a processual space of cultural difference.Footnote11 This state of “in between” may also inform their own authority, enabling them to, as Allserstorfer puts it, “criticize accepted values and practices, both in their homeland and their adopted countries. This criticism lends to certain accents in their work, giving a sense of rootlessness while simultaneously embodying it” (Allerstorfer Citation2013, 184).

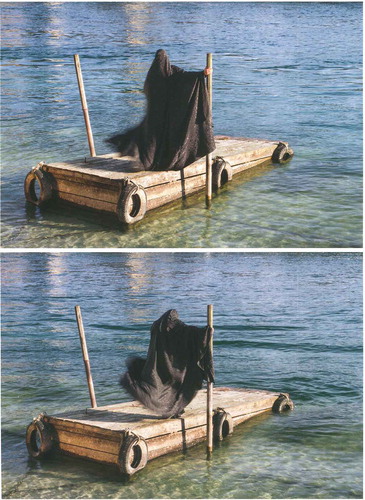

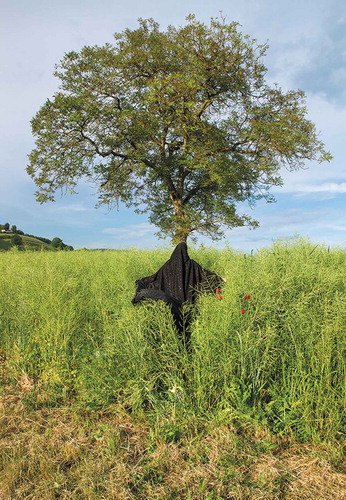

Forouhar’s contradictiveFootnote12 storytelling refers in particular to a notion of rootlessness while simultaneously embodying it. This dichotomy is also recognisable in her latest work Das Grass ist Grün, der Himmel ist Blau, und Sie ist Schwarz, a series of performative photographs that she produced in 2017 during an artist’s residency in the small Swiss border town Stein am Rhein (see a selection ).

In this project, Forouhar deals with questions of identity, emplacement and estrangement. She critically challenges the dynamics of cultural attribution by asking the observer to reflect on his or her own ways of looking at “the stranger” and “the other” and to reconsider them. On the basis of telling “stories of the contradictive”, the artist deals with questions of belonging and the opposites of “proximity or closeness” and “aloofness or detachment”. She metaphorically becomes an anonymous female figure, wrapped in a finely crafted black chador and moving, transitioning, “becoming” in a landscape that does not seem like her own. The person is not clearly identifiable, nor is her story. This photographic series raises different questions and different answers: Who is she? Where is she? And what is she doing there? Where does she come from, and where does she want to go (see )? Does the landscape form a protective space (see )? Or is she in this room to reclaim it (see )? The figure seems to disturb the idyllic landscape by shying away from the viewer and hinting at estrangementFootnote13 yet at the same time merging with it as if they are interdependent.

Within the title “The grass is green, the sky is blue, and she is black” the artist employs wordplay to linguistically and photographically create a new and unknown space. This series, alongside all depictions of black-veiled women in media and art, immediately evokes certain associations. The chador and the veiled woman have Islamic connotations, and are suggestive of a simplistic reduction of the oppression of women. In making use of a garment that has an orientalising, exoticising effect, we might read this image in an almost simplified pictorial language. But if we consider the time, place and cultural setting where the performance is taking place (namely in the small, romantic tourist town on the border of Switzerland) the artistic performance produces multiple meanings. Water (here, the Rhine) (see ) in particular plays an important role in the images.

Referencing current social challenges posed by the “refugee crisis”,Footnote14 the river and the arrival of a chador-clad person are evocative of the Mediterranean Sea, upon which people from African countries and Syria have tried to reach Europe, and within which thousands of lives have met a tragic end. These individuals are often anonymously grouped together as “the refugees”, and perceived by the media and politicians as a “crisis”. They are often understood as strangers invading a region that does not belong to them, and where they themselves do not belong. The figure in Forouhar’s series opens up a similar, but more nuanced reading: the idyllic atmosphere seems to be disturbed by a strange woman occupying a space that was not originally hers. A tense and challenging transformation emerges from the arrival, invasion and subsequent dwelling of the stranger in this idyllic space. This transformation recalls iconic images that document human “invasions” someplace else, such as the stranded refugees at the coastsides of the Mediterranean Sea. Such metaphorical play between the known and the unknown, the visible and the imagined, the near and the unapproachable is a fundamental element of Forouhar’s photographs, and continues to play a role in their curation and means of display.

The works in this project were exhibited in a small local museum in Stein am Rhein called Lindwurm. This museum-house documents the Swiss bourgeois house of the siblings Jakob (1885–1975) and Emma Windler (1891–1988), who were also its last residents. The museum consists of their living room, bedroom, kitchen, and other private rooms as well as the farm buildings and stables. A separate room in the Lindwurm Museum is dedicated to local artist Hermann Knecht (1893–1978) and shows selected works of his, as well as the working materials and furniture of Knecht’s former studio. The curator displayed Forouhar’s photographic series between Knecht’s paintings in the studio, as well as in the private living room and the staircase, thus transforming the photographs into a part of this 20th century bourgeois interior. The ways in which they were hung meant that the photographs sometimes seemed almost invisible and so took on roles as inconspicuous parts of the furnishings. Surrounded by chairs, a monitor showed an interview with Parastou Forouhar in which she discussed her project and her residency in Stein am Rhein—this constituted the only direct link to the artist in the exhibition. During my tour of the museum, I observed visitors fascinated by the small and fine details of the museum in the kitchen and the Mangelstube. However, as a staff member explained to me, hardly any visitors paid attention to the photographic works of the artist. The photographs thus continued their stories of estrangement inherent to the performative acts that the artist carried out in the landscape of Stein am Rhein. This estrangement evolved in multiple ways through the tensions between what was depicted in the photographs and what was displayed in the museum. The entries in the guestbook shed light on the different ways in which the integration of Forouhar’s work was perceived when visitors commented on their dislike or support of this. The variety of reactions strikingly illustrated what this article addressed earlier, that is to say, photography’s potential to mould social relationships and interaction between different groups of people, not only with shared identities but also with contested taste. Whereas some visitors expressed their discomfort upon encountering Forouhar’s photographs dispersed in the nostalgic cultural setting of the museum and its exhibitions, others saw the creative and stimulating potential of such transcultural confrontation. Here the photographs’ potential unfolds as a site where “binary oppositions and antagonism [are overcome] in a common worldmaking”(Petersen and Schramm Citation2017, 2)- and yet also upheld. Even though we do not know the background of the individuals who made each remark, or whether it was the insertion of “foreign” pictures into the nostalgic environment or the stories these photographs told that caused a sense of discontent amongst viewers, the multitude of reactions represent different levels of willingness to recognise and tolerate the representation of an increasing multiculturalism. Such an exhibition space is a particularly contested site for this, in that it may seem to promise a certain imagined traditional and pre-migratory past and worldview.

Diaspora aesthetics—to whom does it speak?

In stating that diaspora aesthetics encompasses “sensuous participation” instead of a merely “sensuous cognition”,Footnote15 Werbner and Fumanti suggest that sensuous participation emerges from the “appreciation and making of beauty, distinction and sheer sensual pleasure as these come to be embedded and re-embedded in social worlds of literary, artistic, musical and performative celebration in diaspora” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 150). In other words, the authors propose that diasporians enact a felt autonomy through sensual and performative media and claim “ownership” of the places and nations in which they settle (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013). However, even though sensuous participation seems to be a component of diasporic aesthetics, it is not the defining element that makes an aesthetic “diasporic”. “Sensuous participation” is arguably also central to non-diasporic forms of aesthetics. Moreover, such a category can be delimited empirically, i.e. as an aesthetic that is distinct from, say, a “national”, an “Iranian”, or a “German” aesthetic. “Diasporic aesthetics” should thus rather be seen as an analytical perspective. In this role, it can be used to argue against a diasporic discourse in migration studies.

The analysis of art in migratory contexts allows for the investigation of complex and all-encompassing processes of social, cultural and institutional change. In other words, the tangible and intangible notions of home, of social participation, and of identification are deeply inscribed into the social practice of photography and its aesthetics. Stressing multiple senses of belonging and multisensory aesthetic production, aesthetics produced by migrants also generate communication and dialogue beyond members of certain (non)migrated communities. Instead of focusing solely on diasporic aesthetics, we should shed light on the postmigratory situation—the moment when migration becomes a given fact to many, or when art and photography “materialize spaces in which it may be possible to engender forms of embodied and participatory worldmaking that challenge the limits of exclusive and normative citizenship” (Meskimmon Citation2017, 33). When art, as we have seen in the case of Parastou Forouhar’s series, provides “experimental opportunities to explore the mutual emergence of transversal worlds and intersectional subjects—or worldmaking denizens” (33), aesthetics intensively shape the process of “becoming” rather than “belonging”. This becomes particularly true “[t]o the extent that they [diasporic aesthetics] reach beyond the encapsulated diaspora group, [since] the aesthetic works of diasporic artists have the capacity to ‘interrupt’ cultural narratives of colonial hegemony or national singularity, …” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 152). In this sense, Petersen and Schramm’s question as to how “contemporary artistic narratives contribute to the ‘storying’ of postmigrant and transcultural belongings” (Petersen and Schramm Citation2017, 2) may be answered: “they provide us with vantage points from which to consider the mechanisms of othering and racism that can help us overcome the ongoing racialisation of those members of societies who are perceived as ‘other’” (Petersen and Schramm Citation2017).

Investigating professional Iranian photographers in the field of art and photo-documentation in Germany and Europe provides a particular perspective in which a cultural and socio-historical complexity is formed through compelling transnational visual and aesthetic regimes. Within this, artistic photography in its multiplicity plays a central role. Since photographic regimes span mass and state-controlled media in the host-country, local documentation, and international media, photography as a medium of art (and documentation) strengthens the idea of a counter narrative to the creation of the oriental “other” or a stereotypical presentation of Iran. For example, photographer Mina Esfandiari, whose photographs are published in Iran. Tausend und ein Widerspruch (Orth, Zuder, and Esfandiari Citation2017), explained to me that

in our talks [during the book tour for the book] I also began to understand which responsibility we as photographers and journalists have—because we provide at this occasion a new view on Iran—and the most of our audiences (many of course non-Iranians) perceived the information as very helpful (but we received also very often approval by Iranians).Footnote16

Approaching photography in its conceptual artistic and documentary sense shows, as becomes apparent here, that it represents but also generates manifold notions of certain diasporic communities and their respective home countries. It is thus possible to conceive of photography as a social practice of communication and consumption, of documentation, and of cultural expression and identification that is fundamentally embedded in and contributes towards the establishment of social relations between migrants and their different generations, among their diasporic communities, and with members of the host society. Saying so, and as the main argument here also contends, artistic photography is a social practice and thus not only an individualist creative one. As a social practice, artistic photography carries the potential to engage different social groups of different diasporic communities as well as members of the host society. In the case of Parastou Forouhar, the complexity of her lifeworlds and her belonging to different groups and communities is obvious: as an internationally renowned and interconnected artist, as a political activist, the daughter of Parvaneh and Dariush Forouhar and in close contact with their fellow activists but also their relatives in Iran and abroad, as an art teacher to students in Germany, as a mother of two sons, etc., “becoming” as a process of belonging is clearly ongoing. Even though, or perhaps even because Forouhar is engaging in different social and diasporic groups and receiving support and recognition as well as critique and rejection for these multiple activities and practices, this perspective deserves to be foregrounded and elaborated upon, much like Meskimmon’s notion of worldmaking. Forouhar’s artistic photography in the context of exile and migration and political action is strongly influenced and inspired by her personal migratory experiences and lifeworlds that are deeply shaped by processes of “tensional and antagonistic struggles for resources, recognition, power, and influence that are also part of culturally diverse societies” (Petersen and Schramm Citation2017, 2). Such societies, and postmigrant societies in particular, must be conceived of in their qualities and potentials of pluralisation, transformation and negotiationFootnote17 in which both the consumption and taking of photographs cumulate in cultural, social and symbolic capital (Bourdieu Citation1996).

Final statement

We can find manifold interpretations in and of Parastou Forouhar’s work: of irony and mimesis, of performance and the female body, of the multitude of identification and belonging, or of stereotyping and of criticism. At the beginning of this article, I argued that the history of Iranian migration to Europe reveals a transnational, cosmopolitan genealogy of Iranian diaspora and exiles, and that such a focus certainly risks suggesting that cosmopolitanism or internationalism is somehow inherent to Iranian diasporic art. As this would exclude art produced inside the country, we must be similarly reflective when foregrounding the efficacy of the term diaspora, so as to ensure that it does not reintroduce a regionalist or post-colonialist discourse. In this context, and in referencing Marsha Meskimmon, Anne Ring Petersen, Moritz Schramm and Sten Pultz Moslund, and the question as to which role photography as social practice in its transnational dispersion can play here, this discussion of a postmigratory situation allows some necessary corrections to be made to the discussion around diasporic aesthetics. Accordingly, we must also differentiate between different kinds of temporalities, as well as the cultural and historical plurality of diasporic life worlds and their diversities in order to estimate the role of diasporic aesthetics in a transnational visual regime of representation. In this regard, the artist Parastou Forouhar represents an interesting agent. Forouhar belongs to a generation of Iranian exiles who experienced the cultural revolution of 1979 in Iran, and although she lives in a self-imposed exile in Germany, she (for now) has the ability to travel back and forth between Germany and Iran. Although she is politically active in her artistic practices, and is very responsive to social grievances in Iran in particular, other works such as the photographic series The Grass is Green, the Sky is Blue, and She is Black stress her transnational engagement with migration, flight and forced displacement. In this photographic series, rather than uphold notions of belonging to a certain community or a national identity, Forouhar subverts any possible boundaries between different diasporic groups and cultural and societal contexts.

In initially questioning the role of visual and performative strategies of storytelling as fundamental for expressing belonging to a host society, I intended to draw attention to photography as social practice in transnational diasporic settings. In conclusion, we might agree with Werbner and Fumanti that a transnational appropriation of aesthetics and embodied performative traditions point to a transformational power of mimesis: “that which appears on the surface to be derivative and imitative, taken from elsewhere, engenders authentically felt cultural competences and a subjective sense of ontological presence” (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 151). Thus, diasporic sociality and aesthetic cultural performance lay the foundations for appropriation and ownership in the alien place of non-ownership (Werbner and Fumanti Citation2013, 171).

However, and as this essay has further explored, such processes should never be perceived as imposing a “being in the world” as a “presence in the diaspora” upon artists in migration contexts such as Parastou Forouhar, nor should they be taken to represent a final state of belonging. Rather, they should be understood as “becoming to belong”. Alongside the photographic series The Grass is Green, the Sky is Blue, and She is Black, I have illustrated the ways in which Forouhar seeks to “interrupt” and challenge cultural narratives of national singularity that are still inherent to the notion of a transnational diaspora aesthetics. In contrast to reinventing national identification and differences between an “us” and a “them”, Fourouhar’s art can be understood as seeking to build social bonds among different social groups in and beyond certain local contexts. Even though ethnic and national distinctions remain important for a conceptualisation of diaspora aesthetics as well as a sense of community building and belonging at times, it is similarly necessary to acknowledge postmigratory contexts and the diverse addressees and audiences that artistic photography can show us. As these works are in many cases produced for non-Iranian audiences with and without migratory backgrounds, stereotypes such as those of a person wearing a chador seem to become troubled, or at least questioned.

Extending my attention not only to artistic photographers but also to photographers in various other fields such as photo-documentation, I wish to conclude by indicating that photography, like documentarian and cinematic film-making, can generate a sensorium, a space that provides possibilities of critical cultural engagement and encounters in postmigration societies, and beyond a single accented dimension of a diasporic aesthetics. Within different professional genres, artistic photography cultivates distinctive “visualities” or “ways of seeing” and allows alternative perspectives to emerge in contrast to images in mass- and state-controlled media. It has the potential to provide a medium of memory, nostalgia, and critical engagement with political situations in various cultural contexts and for different communities. Since such genres are sets of social practices, aesthetic conventions and “semiotic ideologies”, they condition how people make (and make sense of) photographic images, and how this interlinks with either members of different diasporic groups or their own personal knowledge, unified in a transcultural and postmigration situation.

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by Baden-Württemberg Foundation and the Elite-PostDoc Program. I thank Professor Anne Ring Petersen (Copenhagen University) who provided her expertise and comments that greatly improved the manuscript. I thank Parastou Forouhar who provided insights to her work that greatly assisted the research, and Mhairi Montgomery for her support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cathrine Bublatzky

Cathrine Bublatzky is assistant and research fellow at the department of Visual and Media Anthropology at the Heidelberg Centre for Transcultural Studies. She is coordinator of the network “Entangled Histories of Art and Migration: Forms, Visibilities, Agents” (funded by the German Research Foundation). In 2017, she was awarded a grant by the Elite PostDoc Programme of the Baden-Württemberg Foundation to investigate professional photographers from Iran who live in the european diaspora and work in the field of photo documentary and art. Bublatzky’s research interests are based in South Asia, the Middle East and Europe, and include themes such as visual cultures, contemporary art and photography, museums and exhibition studies, and migration and urbanity. Her monograph, Along the Indian Highway: An Ethnography of an International Travelling Exhibition, was published with Routledge India in 2019.

Notes

1. Mehdi Bozorgmehr expressed this concern during a “thematic discussion” at the Middle Eastern Studies Association (MESA) conference “Whither the Iranian Diaspora? Methodological Questions for Scholars and Activists,” San Diego, CA, 12 November 2010. Quoted in Elahi and Karim (Citation2011).

2. Translated to English by the author.

3. The term originates in discourses about migration and integration in Europe and in Germany in particular. It has been covered in a variety of social disciplines and the humanities such as migration studies (see Yildiz and Hill Citation2014; Hill and Yildiz Citation2018), political sciences (see Foroutan Citation2019) or cultural and art studies (see Petersen and Schramm Citation2017; Schramm, Moslund and Petersen Citation2019) and anthropology (see Römhild Citation2017).

4. Meskimmon (Citation2017). In reference to Moritz Schramm’s paper “Postmigration: A New Turn in Cultural Studies?”, delivered as a keynote during the Research Seminar Trans-Formations: Travelling Cultures, Cosmopolitan Identities and Migratory Memories, Sandbjerg, Denmark, April 2016.

5. The notion of social practice goes beyond Pierre Bourdieu’s class-oriented approach to the social definition of photography (1990/1996) but envisages an understanding of dynamics, processuality and social relationality.

6. See for example Helff and Michels (Citation2018).

7. In my understanding of postmigration in the field of art and migration, I refer to Anne Ring Petersen and Moritz Schramm (Citation2017) who argue that the term does not primarily refer to the temporal situation “after” migration. When they pose the question “how can art and culture contribute to the creation of new modes of representation, interaction, and recognition in so-called multicultural or postmigrant societies?” (2), they are also interested in forms of “re-narration and re-interpretation of the phenomenon ‘migration’ and its consequences” (5–6), Petersen and Schramm (Citation2017).

8. For an extended discussion of the artist Parastou Forouhar see also Bublatzky (Citation2019).

9. Forouhar (Citation2011, 9; translation into English by the author).

10. Parastou Forouhar in an skype interview with the author on 24th of May 2017.

11. See for this discussion Naficy (Citation1999; Citation2001).

12. Parastou Forouhar in an skype interview with the author on 24th of May 2017.

13. My thanks goes to Ring Peterson and Burcu Dogramaci for their helpful comments in opening my discussion of these practices.

14. The term “Refugee crises in Europe” was coined in the context of the massive increasement of refugees and migrants, especially since 2015.

15. Werbner and Fumanti refer to Wiseman (Citation2007).

16. Mina Esfandiari in an email conversation with the author on 16th of April 2018.

17. See for this discussion, for example, Foroutan, Karakayali, and Spielhaus (Citation2018).

References

- Allerstorfer, J. 2013. “Performing Visual Strategies: Representational Concepts of Female Iranian Identity in Contempoary Photography and Video Art.” In Performing the Iranian State: Visual Culture and Representations of Iranian Identity, edited by S. G. Scheiwiller, 1–10. London: Anthem Press.

- Axel, B. K. 2002. “The Diasporic Imaginary.” Public Culture 14 (2): 411–428. doi:10.1215/08992363-14-2-411.

- Bourdieu, P. 1996. Photography: A Middle-Brow Art. 1st ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bublatzky, C. 2018. “Fotografie – Ein Transkultureller Verhandlungsraum. Eine Analyse Der Arbeiten von Ravi Agarwal (Delhi).” In Kulturelle Übersetzer: Kunst Und Kulturmanagement Im Transkulturellen Kontext, edited by C. Dätsch, 115–131. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Bublatzky, C. 2019. “Memory. Belonging. Engaging – Artistic Production in a Migration Context.” In Handbook of Art and Global Migration: Theories, Practices, and Challenges, edited by B. Dogramaci and B. Mersmann, 281–297. 1st ed. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Elahi, B., and P. M. Karim. 2011. “Introduction: Iranian Diaspora.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 31 (2): 381–387. doi:10.1215/1089201X-1264307.

- Forouhar, P. 2004. “Veiled – Unveiled.” Accessed June 19, 2019. https://www.parastou-forouhar.de/veiled-unveiled-parastou-forouhar-2004/

- Forouhar, P. 2011. Das Land, in dem meine Eltern umgebracht wurden: Liebeserklärung an den Iran. 1st ed. Freiburg im Breisgau: Verlag Herder.

- Foroutan, N., J. Karakayali, and R. Spielhaus. 2018. Postmigrantische Perspektiven: Ordnungssysteme, Repräsentationen, Kritik. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Foroutan, N. 2019. “Die Postmigrantische Gesellschaft.” Ein Versprechen Der Pluralen Demokratie. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Grassian, D. 2012. Iranian and Diasporic Literature in the 21st Century: A Critical Study. Jefferson: McFarland.

- Helff, S., and S. Michels, eds. 2018. Global Photographies: Memory - History - Archives. Image, Vol. 76. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Hill, M., and E. Yildiz, eds.. 2018. Postmigrantische Visionen: Erfahrungen, Ideen, Reflexionen. Postmigrantische Studien, Band 1. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Karentzos, A. 2006. “Unterscheiden des Unterscheidens. Ironische Techniken in der Kunst Parastou Forouhars.” In Der Orient, die Fremde. Positionen zeitgenössischer Kunst und Literatur, edited by R. Gökede and A. Karentzos, 127–138. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Meskimmon, M. 2017. “From the Cosmos to the Polis: On Denizens, Art and Postmigration Worldmaking.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 9 (2): 25–35. doi:10.1080/20004214.2017.1343082.

- Naficy, H., ed. 1999. Home, Exile, Homeland: Film, Media and the Politics of Place. AFI Film Readers. New York [u.a.]: Routledge.

- Naficy, H. 2001. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton Paperbacks. Princeton, NJ [u.a.]: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Orth, S., S. Zuder, and M. Esfandiari. 2017. Iran: Tausend und ein Widerspruch. Der wunderschöne Bildband zum Bestseller »Couchsurfing im Iran« von Stefan Orth. 1st ed. München: NG Buchverlag GmbH.

- Petersen, A. R., and M. Schramm. 2017. “(Post-)migration in the Age of Globalisation: New Challenges to Imagination and Representation.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 9 (2): 1–12. doi:10.1080/20004214.2017.1356178.

- Quayson, A., and G. Daswani, eds. 2013. A Companion to Diaspora and Transnationalism. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. doi:10.1002/9781118320792.

- Römhild, R. 2017. “Beyond the Bounds of the Ethnic: For Postmigrant Cultural and Social Research.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 9 (2): 69–75. doi:10.1080/20004214.2017.1379850.

- Schramm, M., S. P. Moslund, and A. R. Petersen. 2019. Reframing Migration, Diversity and the Arts: The Postmigrant Condition. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sullivan, Z. 2001. Exiled Memories: Stories of Iranian Diaspora. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Werbner, P., and M. Fumanti. 2014. “The Aesthetics of Diaspora: Sensual Milieus and Literary Worlds.” In Arts and Aesthetics in a Globalizing World, R. Kaur edited by, 153–169. ASA Monographs; 51; Association of Social Anthropologists of the Commonwealth. Bloomsbury: London.

- Werbner, P., and M. Fumanti. 2013. “The Aesthetics of Diaspora: Ownership and Appropriation.” Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 78 (2): 149–174. doi:10.1080/00141844.2012.669776.

- Wiseman, B. 2007. Lévi-Strauss, Anthropology and Aesthetics. 1. publ. Ideas in Context 85. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Yildiz, E., and M. Hill. 2014. Nach der Migration: Postmigrantische Perspektiven jenseits der Parallelgesellschaft. 1., Aufl. Bielefeld: Transcript.