ABSTRACT

This article looks at the photographic parts of the archive of racial biology in Uppsala, Sweden. This material is approached both through works by Swedish Sámi artist Katarina Pirak Sikku as well as through close engagements with the archive itself and its historical circumstances. In the article, the focus is on affective and emotional relations to the archival photographs and the events of their creation. I argue that Pirak Sikku’s profound emotional and physical working through of this material has opened a path for others to engage with this archive beyond only seeing it as a concretisation of a highly problematic and dangerous “scientific” practice. Furthermore, I suggest that examining the emotional, embodied and affective aspects is necessary to achieve further understanding not only of this particular archive, but also of harrowing periods of history in general. Finally, I show how an engagement such as that by Pirak Sikku is able to open up perspectives from which care and inquisitiveness can be seen to triumph over even the deepest injustices.

In 1921, Sweden became the first country in the world to open a State Institute for Racial Biology. Herman Lundborg, a Swedish physician, was appointed head of the institute. Under his leadership, the institute began collecting anthropometric statistics and photographs mapping the racial make-up of Sweden’s population. By 1935, Lundborg had been replaced by Gunnar Dahlberg and the institute had changed its focus from racial biology to medico-genetic and socio-medical research. Its racial biology archive had also become the largest in the world. Today, held by the library of Uppsala University, 12,123 photographs, 105 albums, and a number of folders remain from this research.

In the present article, I focus on the photographic part of this archive. The photographs are examined from two perspectives: firstly, through the works of Swedish Sámi artist Katarina Pirak Sikku and, secondly, through my own engagement with the archive and its historical circumstances (Larsson Citation2018).Footnote1 In both cases, focus is on the affective and emotional reactions to the photographs and the circumstances in which they were taken.Footnote2 While much attention has been given in the last years to archival studies, including artists working critically with archives, the archive of racial biology has not been studied from a perspective of critical artistic engagement, nor from a perspective of emotions and affect. I argue that Pirak Sikku’s profound emotional and physical working through of this material has opened a path for others, such as myself, to engage with this archive on a different level. Furthermore, I suggest that examining the emotional, embodied and affective aspects is necessary to achieve further understanding not only of this particular archive, but also of harrowing periods of history in general.

A heterogeneous archive

Some 80 years before the opening of the State Institute for Racial Biology, Swedish anatomist Anders A. Retzius had devised a system of “racial classification” based on so-called “long skulls” and “short skulls”. The former were considered to be characteristic of a higher race and the latter of a separate and less intelligent race (Hagerman 2006). These races were regarded as separate and, additionally, racial interbreeding was seen as unnatural and even dangerous. Through comparisons of, for example, horses and donkeys, it was believed that interbreeding led to bastardisation, sterile offspring and, eventually, “extinction” (Hansson and Lundström Citation2008). This latter did not concern the researchers; nature would ensure that “low” races did not survive. However, for the “higher” races, there was a great risk of “contamination”. Thus, especially in places such as northern Scandinavia where different “races” cohabited, it was important to implement measures to prevent, as far as possible, such interbreeding.

For the researchers of the State Institute for Racial Biology, the ideas embodied in the long-skull and short-skull categorisation were key. Under this categorisation, the Nordic or Germanic parts of the Swedish population were long skulls, while the Sámi and Finnish parts were regarded as belonging to the lower category (Keane Citation1886).Footnote3 Lundborg and the institute were particularly interested in the Sámi populations of northern Sweden. To anthropometrically measure and document the Sámi populations of Sweden, Lundborg made a number of research trips to Swedish Sápmi between 1922 and 1935. In these documentations, photography was used as the main tool to provide evidence supporting the proposed theories.

Although, at that time, theorists were already reflecting on the limits of photographic objectivity, many scientific fields still held strong to the belief in the medium’s neutrality.Footnote4 It was assumed that, as there was no “mediator”, photographic technology disinterestedly recorded visual “facts” that could prove researchers’ theories. However, there seems to be a lack of “scientific rigidity” in the actual make-up of the different parts of Lundborg’s racial biology archive. At that time, the standard format of ethnographic research was to take three photographs of each subject in front of a neutral background (in the case of the research in Sápmi often a sheet hung to form an improvised on-site studio). One would be taken from the front, one from a 45-degree angle and one from the side. While many of the photographs in the archive follow this, many others were taken in a variety of formats (full-length, waist-up, seated, standing, couples, groups, families, siblings, in the countryside, in front of homes, indoors, at kitchen tables, etc.). Similarly, the subjects’ expressions are equally varied (disconcerted, aloof, smiling, frowning, “confronting” the camera lens, avoiding it, etc.) (Azoulay Citation2008).Footnote5

There are several possible reasons why the archive is not the precise systematic documentation ostensibly favoured by researchers.Footnote6 Below, I reflect on the inherent ambiguity of any photographic archive. However, there are also various “practicalities” behind the archive’s “diversity”. As mentioned, Lundborg (along with his crew of assistants and technicians) made several research trips collecting parts of the documentation. In addition to this material, large parts of the archive were also collected from a number of different sources. In the early stages, newspaper notices were employed to ask people to submit photographs that could be used in the research. Hence, the various parts of the archive have not only photographs from many different photographers, but also many series taken in a number of different ways and circumstances. Additionally, there was also a habit of exchanging photographs between archives in different countries. It was not uncommon for the same photographs to be used as “evidence” in different publications in different countries.Footnote7 Even in the collections of photographs devoted to Swedish Sápmi (the ones with which Lundborg himself was primarily involved), there are contributions from several different photographers and a variety of settings were used. Gunhild Sandgren, one of the photographers contracted to take pictures for part of the archive, accompanied Lundborg on several documentation trips in northern Norway. So too did Nils Thomasson, a Sámi photographer who photographed Sámi (especially those in Jämtland).

Throughout the last decades, critical archival theory has bought attention to how ideology plays a part in the creation and reinforcing of different kinds of historical and contemporary archives (Larsson Citation2018).Footnote8 Although the diversity of the archive of racial biology is contrary to the precept of scientific rigidity, it is possible to see how this diversity served a purpose as regards the theories/ideology the archive sought to substantiate. At a fairly early stage of the research, it became clear that the documentation did not support the theory of there being separate human races that differed qualitatively in their evolution. However, as detailed by Ulrika Kjellman, this theory could then be used in interpreting the archive’s “surplus, ambiguous” images. As Kjellman points out, even though the theory of racial biology was based on differences in human bodies, there was actually less focus on bodies in the actual archive then one would expect. Clothing, buildings, interiors and nature feature prominently in a large part of the material. This diversity enabled Lundborg and other supporters of racial biology to select examples that matched the theory they advocated. When the documented bodies alone did not substantiate the theory (and its derivatives), it was still possible to interpret compliance via clothes and environments whilst, paradoxically, still relying on the supposed objectivity of photographs as scientific evidence.

Many of the photographs also show how different individuals and groups were photographed in different ways depending on racial attribution. For example, part of the collection comprises portraits of different classes of workers. Here, professions that were considered to make significant contributions to society were exemplified using the Nordic race. Other professions were exemplified using “lower” or (at the very bottom of the evolutionary ladder) mixed races. As Kjellman puts it, for the State Institute of Racial Biology, the significance of photography could not be understood in terms of it being exploited as a scientific tool (although the researchers themselves would, of course, have argued that this was precisely the case) but rather as a tool of political ideology or propaganda. This is further exemplified by the fact that, after 1935, when the institute gradually started to move away from racial sciences in order to focus more on medico-genetics, the use of photography as a tool became of decreasing significance.

An emotional process

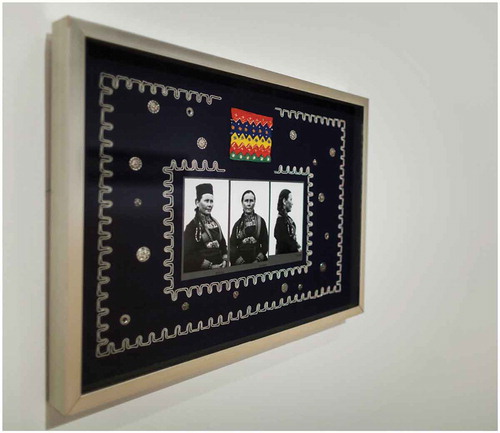

Katrina Pirak Sikku is a Swedish Sami artist who works in a range of different media, including drawing, photography, painting, installation and text. She spent ten years researching the parts of the archive of racial biology that focuses on the Sami population. Her research culminated in the exhibition Nammaláhpán, which has been held in several places in Scandinavia. In the works included in this exhibition, the ideology above appears in several shapes and forms. In addition to spending several years going through the pictorial and written material in the archive, Pirak Sikku also interviewed people who were documented and anthropometrically measured as well as relatives of those who took part in the research, in order to understand how memories of the appertaining events still live on today. She also travelled back to the sites where documentation took place. Of Pirak Sikku’s many works emerging from this process, only one, Ánná siessá (Aunt Anna) (2014), contains actual archive images (Image 1). These photographs are of Anna, the aunt of Elsa Teilus. This latter is a friend of Pirak Sikku’s family and accompanied her on some of the journeys to where the research was carried out. Pirak Sikku describes how, while they were looking through some of the archive images together, Elsa recognised her aunt Anna in one of the photographs.Footnote9

In the section of the archive in question, there are three images of Anna. They were taken in conformity with the protocol requiring one photograph from the front, one from an angle and one from the side. In the images, Anna is wearing traditional Sámi clothing. In the first image, she has a hat. In the other two, her hair (pulled back, braided, decorated, and hanging down her right shoulder) is visible. She is sitting proudly and her expression is stern, but not unsympathetic. According to Pirak Sikku, it was the pride and beauty emanating from the subject (who had not then been identified) that made her want to take the images from the categorising and systematising section of the archive and present them to the world.

In the archives, the three black and white photographs were attached to grey card. Below each image, there was an identification number referring to the anthropometric measurements found elsewhere in the archive. Pirak Sikku explains how, while Elsa had, up until then, claimed to have no recollection of being part of the research, the memories of being measured and documented as a child returned when she saw the images of her aunt. “I was cold,” she said, “we were freezing”.Footnote10 Before these memories resurfaced, Elsa had previously described the feelings of shame surrounding the process of being measured and documented: “We were embarrassed about being ‘Lapps’. It was something ugly”.Footnote11

In selecting these images from the archive and putting them into an exhibition, Pirak Sikku has stated that she did not want to repeat the structure of the circumstances in which they had been taken. For this reason, and as an act of caring not only for the photographs but also for the woman portrayed in them, she made a pewter-thread embroidered frame for the images. She also included a piece of the traditional clothing that Elsa had worn on the day the photograph was taken.Footnote12 Remarkably enough, Pirak Sikku’s concern about not echoing the archive structures in the new, gallery setting extended to the researchers too. She expressed how she did not want them to be “exposed” on the gallery wall without their consent.

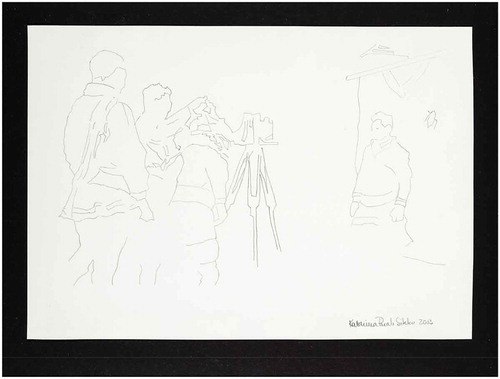

Pirak Sikku’s Badjelántta luottat (Traces from the Land Above—2013) covers how Lundborg’s research was carried out in Sápmi. Besides archive documents and photographs revealing how the anthropometric research was performed, the work also uses materials regarding the Sápmi sites where said documents and photographs came into being, which Pirak Sikku visited. Badjelántta luottat consists of different works using different materials, including Pirak Sikku’s own photographs of the sites and the surrounding countryside. However, rather than include the archive’s own photographs of the researchers at work, Pirak Sikku made her own drawings of the photographs. The drawings use thin contours to outline the researchers and their equipment. The person being documented is also shown at times. However, the settings (countryside, objects, etc.) are not depicted. In most of the drawings, faces are shown only through contours. In some, a line or two is included to show the eyes or mouth of one of the researchers. There is no way of identifying either the individuals involved or the place where the photographs were taken. At the same time, the drawings are highly suggestive of the research process. For example, equipment is carefully outlined both when packed for carriage on someone’s back and when assembled (camera on its tripod and a sheet extended behind the subject who is about to be photographed).

One of the images (Image 2) outlines four people seemingly in the process of preparing for a photograph to be taken. Three of them are standing around the camera. The other, arms hanging down, is outlined in front of what appears to be a sheet. Lines across this latter person’s chest suggest equipment and that he or she is part of the team participating in the preparations (rather than someone being documented). Although there are no facial expressions or even lower bodies, the outlines give a clear sense of the postures, clothing and equipment being used. The focus is on the process itself; in this case, using photography to achieve the aims of this piece of “scientific research”. Meticulously arranged backpacks, the postures of the people carrying them and their attentiveness to the process and above-mentioned equipment all suggest that the research was carried out with great seriousness. This gravity can also be found in many of the documents published by the institute.Footnote13

Emotions and affects play a significant role, in both the works touched on above (Ánná siessá and Badjelántta luottat). In Ánná siessá, feelings of shame and of violation invoked a response of caring not only for the archive photographs but also for the portrayed woman and her niece (who recalled the aforementioned feelings when seeing the photographs). In Badjelántta luottat, affective aspects of the documentation process are brought out through the stylised drawings. Pirak Sikku has detailed how her artistic process began with a strong feeling of anger, mainly directed toward Lundborg as an individual and his manifestation of the belief system that underpinned his research. However, this emotional relationship changed over the several years that she worked with the material. She experienced a range of different affects and emotions directed to the diverse aspects of the archive and the processes involved in its creation. Pirak Sikku has explained how, in the beginning, the emotions were more one-directional. Through the process of engaging, they became more multilayered and involved shades of grey rather than just black and white. In particular, she has related how feelings of love, care, inquisitiveness and empathy became important parts of the artistic process.

In the course of the last two decades, the notion of care has become prominent in fields such as feminist -, cultural—and social sciences. Feminist critical theorist Nancy Fraser has written about the importance of “care work”—and about how this kind of work is at the same time severely devalued in capitalists societies (Fraser Citation2013). Feminist political theorist Nira Yuval-Davis similarly places much emphasis on the ethics of care in her writings. She has, for example, written about “the extent to which caring and love can counteract other emotions as the normative basis of political action” (Yuval-Davies Citation2011, 178). She brings up a number of other authors (including Carol Gilligan, Eric Gregory and Virginia Held) who emphasise an “ethics of care” as a way of criticising common liberal discourse which “find little room for affectivity and emotions except as natural energies to be constrained by reason” (Gregory Citation2008, 151). The discussion of care in writings such as that of Yuval-Davies, Fraser and others, however, often argues about the significance of care from an abstract theoretical position. In contrast, I suggest that Pirak Sikku’s personal and long-lasting working through of the different aspects of the archive brings this argument into a concrete and embodied situation, in which the notion of care (as well as the other emotions, affects and reflections that appear) can be explored in their particular materiality as well as the specific situated, historical and cultural situation within which they exist.

In Ánná siessá, care is expended on the material images of Anna rather than on a physical body. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of this focus on the images, it becomes a way of working through the feelings of shame, anger and sadness that both Pirak Sikku and Elsa talk about in relation to the archive images and the project of which these were a part. Whereas Ánná siessá is a highly emotional piece that counteracts the feelings of shame through love and care, Badjelántta luottat responds to the emotion of anger through inquisitiveness. Without in any way justifying the project or the ideology that underpinned it, the initial documentation process is engaged with through an open inquisitiveness about the affective experiences (researchers not excluded therefrom) in the said process. Rather than moving away from these experiences, Pirak Sikku moves closer to them and examines the details. These latter include the postures of the individuals involved, the felt sense of the equipment and the acts involved in creating the documentation.

It is clear that the process of working with and working through this material was highly emotional. Strong emotions have also been expressed by others exposed to the works in some way or another. In Affective Economies, Sarah Ahmed challenges, as she puts it, “any assumption that emotions are a private matter, that they simply belong to individuals, or even that they come from within and then move outward toward others” (Ahmed Citation2004, 117). She also presents a view of emotions as “circulating between bodies and signs” (Ahmed Citation2004). In such a system, there is no working through that is strictly personal. In the case of Pirak Sikku’s artistic process, the emotional working through took place in interactions involving: the artist; the archive itself; the archive staff; the places travelled through in retracing the researchers’ steps; the countryside Pirak Sikku encountered in the retracing; the people that accompanied her and with whom she interacted in said retracing; the people that she discussed; and, the people with whom she shared some of the archive material. Exhibiting the works expanded this arena of collaboration even further.

Pirak Sikku has detailed how emotions have often been expressed in and through stories and memories connected to aspects of the research and this latter’s repercussions throughout subsequent decades. Though told by a number of different people, several stories emerging from interviews by Pirak Sikku and exposure to her works have common themes. One of these is the memory of photographs that were retained by families and around which there was some level of unspoken controversy. In some stories, the photographs were hidden away in boxes and there was an unspoken sense of not wanting them to be seen. One woman recounted childhood memories of a framed photograph of her father. She described how her mother would put the picture up on the wall and how her father would take it down. This pattern was repeated throughout her childhood. It was only when her father was quite old that he explained his actions. He had memories of once being documented as part of the racial biology research. These memories bore with them a strong sense of shame. The photograph itself revealed nothing of this.

On shame

In recent years, philosopher Martha Nussbaum has written extensively on emotions in relation to political life. When discussing the emotions of shame and guilt, she describes how these are often used interchangeably as painful emotions directed at the self. Nevertheless, in defining these two types of affective expressions, she points out how there is an important conceptual difference between them. While guilt has to do with things that one has done or aims to do, shame relates to a more abstract sense of being wrong in some way or of having some more general trait that is considered undesired. Significantly, Nussbaum makes a strong connection between stigmatised minorities and feelings of shame. While every society has their own categories of stigmatised groups, Nussbaum mentions some as fairly constant: “racial, ethnic, and religious minorities, sexual minorities, lower-class workers, the unemployed, and people with disabilities” (Nussbaum Citation2013, 360). Nussbaum presents a theory of how most people (those of the dominant group included therein) either have traits of which they are ashamed or, at least, fear that they have such traits. She describes the psychological relief of projecting this shame onto others. It is through such projection that the dominant group characterises itself as “normal” and the divergent group as shameful, “asking them to blush for who and what they are” (Nussbaum Citation2013). Significantly, Nussbaum relates that hiding is the natural reflex reaction to shame. In the stories told to Pirak Sikku (see above), the hiding of photographs taken as part of the research is a recurrent theme. In the particular example of hiding given above, the content of the photograph itself did not reveal anything about the feelings of shame connected with it. Rather, the feelings of shame are the result of the memories, thoughts and associations connected with the photograph.

Nussbaum argues for a view of emotions not as biological impulses, but as constructs within particular contexts. More specifically, Nussbaum describes emotions as necessarily involving cognitive appraisals. These she describes as “forms of value-laden perception and/or thought directed at an object or objects” (Nussbaum Citation2013, 17). In other words, in contrast to a view of emotions as biological entities, Nussbaum argues that emotions always involve some kind of judgement.Footnote14 As a corollary of this, emotions are not engendered within subjective bodies, nor from any external object, but through cognitions engendered by the surroundings. In the case of the putting up and taking down of the framed portrait, the photograph itself tells us little about the surrounding events. Any emotional affinity with the image depends strongly on the cognitive appraisals that are linked to or invoked in relation to the object. As I expand upon below, this adds to the understanding of how the same set of images can be used in such diametrically different contexts and conjure such diametrically different emotions, as well as how the emotions around a historically charged object or event can change with time.

It is clear that the emotion of shame plays a significant role not only in the Sámi context of the archive and its history, but also in the reactions of most people who are exposed to this research.Footnote15 Pirak Sikku has explained how, throughout her artistic process, she would often find herself wondering when this emotion of shame was most acutely felt. There is very little information about how the Sámi people experienced and felt about the documentation.Footnote16 Pirak Sikku suggests the possibility that shame was not central to all experiences of being photographed. It is clear that, over time and especially from a Sámi perspective (though also in a mainstream context), the events and the material resulting therefrom were rarely discussed and often hidden. This silence has lasted well into the present century. It is possible that increased understanding of the dubious “science” behind the research and its connections with the atrocities of the Second World War resulted in the shame enshrouding the events themselves taking on a different character. Furthermore, even while the dangers of the “science” were becoming evident, injustices against the Sami continued, including the imposing of borders in Sápmi, bans on speaking Sami languages in schools and elsewhere, as well as missionary interventions in the area.

In her reflections on shame, Nussbaum brings up the “sheer power of culture” (Nussbaum Citation2013). She writes about how even though stigmatised people do not themselves carry the belief that there is something shameful about being themselves, they nevertheless often feel the shame that the dominant culture projects onto them. She also describes how, as humiliating conditions are created for minorities, it is common for minority members to feel shame as regards their existence in these conditions. The recurrent hiding of photographs that surfaces in the stories triggered by the works of Pirak Sikku can be seen as a physical manifestation of the feelings of shame created through such external circumstances.

One way of understanding the path opened by Pirak Sikku’s work is Jalal Toufic’s notion of surpassing disaster (Toufic Citation2009). For Toufic, this notion relates to cultural disasters that not only affect material things, but which also have consequences for immaterial things with which people later have to engage. He describes how it affects books, art, music, images and culture in general. Toufic writes about how surpassing disasters destroy not only material things and bodies, but also the possibilities for practising and experiencing certain aspects of culture. In these circumstances, traditions have to be resurrected by the members of the community affected by the surpassing disaster. This is accomplished by taking care of what has been “withdrawn”. For Toufic, it is thinkers, artists, musicians and other cultural workers who implement this “caring” by, for example, recreating withdrawn movies or artworks or bringing archive images back into the present.Footnote17

In terms of the Sámi culture addressed in Pirak Sikku’s works, the surpassing disaster is not solely the racial biology research. It covers a long and slow process that included, as mentioned above, the imposition of borders in Sápmi, missionary interventions and bans on speaking Sámi languages in schools and elsewhere—of which “racial sciences” were only one part. In the last couple of decades, Sámi research centres have opened in the Scandinavian countries, focusing on the languages, culture and history of Sámi from the perspective of different disciplines. Over the past few years, there has also been an increasing number of artworks attempting to “resurrect” the significance of different aspects of Sámi culture.Footnote18 While there is a great difference between resurrecting Sámi culture and engaging with the racial biology archive’s material, I nevertheless suggest that Pirak Sikku’s “care work” can be understood as a part of such resurrection. The significance of this work becomes all the more apparent when we take into consideration the “silence” and “hiding” that Pirak Sikku and others describe as accompanying not only these historical events but also aspects of Sámi culture in general. Caringly engaging with the archive images in different ways can be seen as one way of concretising experiences that have disappeared from view.

A third perspective

In the last part of this article, I wish to suggest that, by responding to the emotions of shame, fear and anger with love, care and inquisitiveness, Pirak Sikku’s working through of the archive has opened a path for others, such as myself, to engage with this material in ways beyond simply seeing a concretisation of a highly problematic and dangerous “scientific” practice. In his article Our Histories in the Photographs of the Others: Sámi Approaches to Visual Materials in Archives, Veli-Pekka Lehtola writes about experiences of repatriating, over the past fifteen years, ethnological photographs to Sámi societies in Finland. In engaging with these photographs, he describes how the focus is often on community perspectives “revealing ‘small stories’ of us and our ancestors rather than ‘big histories’ of colonial circumstances and contradictions with outsiders’ societies” (Veli-Pekka Citation2018, 1). In the ethnological material that he looked at, the photographers (and even cameras) were often carefully recorded while the depicted people would be unnamed and left to represent a generic cultural or racial category of Sámi. Conversely, in restoring these photographs and the people, friends or families of those portrayed therein to “the local level”, he relates that there would be a reversal of perspectives; the people engaging with the photographs would often ignore the people behind the camera. As Lehtola argues, there are different ways of engaging with the contents of the archives, each one requiring their own interpretive change (Pinney Citation2003, 5).Footnote19

In the aforementioned article, Lehtola discusses a set of photographs of Sámi children in a Norwegian institutional setting reading Norwegian words written on a blackboard. In their original context, the images were primarily used and perceived as evidence of the success of the Norwegian educational system. However, over time, they came to be regarded more critically as illustrations of Norway’s assimilation policy. While this perspective remains highly significant, a third perspective of “our history” (Lehtola’s words) would direct the focus to the individual students in the images, thereby giving rise to questions about who they were, how they felt about the situation, how they lived and what happened to them (Pinney Citation2003, 4).Footnote20

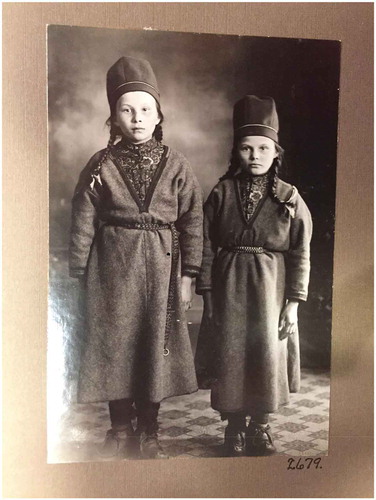

Just as, when examining the archive, Pirak Sikku was struck by the image of Anna, I too, when leafing through the photographs, was affected by one image in particular. The image (Image 3) shows two girls, apparently sisters, looking straight into the camera.Footnote21 As with all the photographs in the albums, at the bottom of the image there is a four-digit number referring to the anthropometric measurements found elsewhere in the archive. In this case, the number is 2679. The girls are standing straight-backed, their arms hanging down their sides. One girl is slightly shorter than the other. They are standing close enough to each other for their arms to be touching. Their expressions are serious, perhaps a little disconcerted. When Pirak Sikku recounted to me her experiences when going through the archives, she talked about how she could get lost for hours in the details of the clothing in many of the images. At times, she forgot both the purpose of her own investigation and the circumstances in which the images were taken. Similarly, in the images of the two girls, I find myself noticing the intricate patterns of their buttoned-up shirts, the smoothness of their felted wool dresses and hats, the design of their embroidered belts, the way their beak shoes are carefully tied together at the ankle, the shine of their hair braids and the ribbons that hold them in place. I also notice the tiled floor and empty wall of what may be a school or some kind of official building in which the documentation took place. What comes across in the image is a feeling of care in the braiding of their hair and the diligence of their clothing. As mentioned, there is a sense of gravity in the way they are looking into the camera. However, what comes across more strongly is a sense of intelligence and earnestness in their expression. It seems as if they are in this building, against this empty wall, because they have been told to be there. At the same time, their focus remains on all that came before this moment in time and all that is to come after, rather than on the moment itself. There is a feeling of fullness to their lives, the taking of the photograph being just a detail in this.

The girls’ existence as part of a system that aimed to categorise human races according to a predetermined hierarchy can, and should, never be ignored. Nonetheless, as Lehtola posits, a number of stances can be taken vis-à-vis archive photographs. Furthermore, another perspective from which to engage with them might give rise to entirely different sets of questions (e.g. regarding the material of the subjects’ clothing, who embroidered the subjects’ belts and how, who braided their hair and arranged their clothing so neatly, who brought them to be photographed, how the subjects felt, what they were thinking about, the temperature in the room, the subjects’ names, what they did before and after being photographed, etc.).

While photographs may appear to tell simple stories, Elisabeth Edwards and others have emphasised how photographs function through complex mechanisms. This is, perhaps, particularly true of archive photographs. Edwards writes about the difference between perceiving photographs as, on the one hand, an expression of some “imagined or reified theoretical world” and, on the other, as “specific photographic experiences” (Edwards Citation2001, 3). In the former, photographs can be reduced to one or a select few particular significations. In the latter, they open up myriad possibilities for different, at times contrasting, interpretations or for different stances to be taken. Writing similarly about photography, and in particular archival photography, as being ambiguous and dynamic, Christopher Pinney discusses the camera’s “inability to discriminate” between what should be in the picture and what should be left out (Pinney Citation2003, 6). He highlights how photographs inevitably include details and aspects of reality that the photographer did not consciously intend to include. This unavoidably leads to what he calls a “margin of excess” within any photograph. For him, it is precisely photography’s inability to discriminate and exclude that makes it “so textured and so fertile” (Pinney Citation2003). There is always some element of randomness to the images; something unplanned is always inevitably included. Following these reflections of both Pinney and Edwards, it is clear that the photograph of the two girls as well as the photographs of Aunt Anna are full of excess and randomness, which enable a different kind of engagement. While not excluding the ideology that caused the images to be taken, such engagement reveals other stories to be told and perspectives from which care and inquisitiveness can be seen to triumph over even the deepest injustices.

As evidenced by the four-digit number at its bottom right, these photographs (as the others in the albums) are inarguably part of the racial biology research used to support the idea of the existence of separate human races and a hierarchy into which this science would order them. However, as a photograph that is emotionally and affectively engaged with, the image exponentially exceeds and even negates this “research system”. While the aim of the research was to reduce the image and the individuals to evidence corroborating a particular ideology, the photographs themselves cannot help but present them as subjects in their own right. In the affective engagement with the excess of information that the image presents, the photograph can be seen as refuting the very system it was meant to substantiate.

Conclusion

While the archive of racial biology in Sweden has only begun to be researched in the last years, and there are few artists that have yet engaged with this archive, the idea of artists “stirring up the archive” is not new. On the contrary, engaging with archives can be seen rather as a trend within contemporary art practices in the last couple of decades. In terms of the subject of archive and affect, Ann Cvetkovich writes in a chapter in Feeling Photography about the archival engagements of queer collections of Tammy Rae Carland and Zoe Leonard from a perspective of embedded emotions (Cvetkovich Citation2014). Also the work of Greg Staats, who uses archival sources of Iroquoian traditions, has been discussed in terms of how his work generates an affective response (Bassnett Citation2009). Countless other artists that work critically with the archive could be brought up here, but to mention a few one could name Inci Eviner and Gülsün Karamustafa (who work with archives that relate to Ottoman and Turkish history), Walid Ra’ad and the artist duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige (that both relate to the destruction of Beirut during the civil war), and Lina Selander (who works with archives relating to a collective European history) (Larsson Citation2018).Footnote22

In terms of the archive of racial biology, I have shown in this article how racial sciences ideology permeates both the archive and the historical events in which this latter was created. At the same time, because of the heterogeneousness of the archive and the inherent ambiguity of the photographs, the archive images themselves cannot help but convey information beyond this ideology (e.g. about the emotional and affective experiences of being documented and of documenting, about the sites where the research took place and, not least, about the individuals that were involved). Furthermore, I have suggested that the long and slow process undertaken by artist Katarina Pirak Sikku in relation to the archive material creates a path via which there can be engagement with these experiences.

As regards photographs (archive photographs in particular) and harrowing events in history in general, the emotional and affective aspects of engagement are often overlooked. While it is crucial to expose and deconstruct the ideology that claimed to justify the racial biology research project, I suggest that it is through processes such as that embarked on by Pirak Sikku that it becomes possible to respond to pain and shame with care and compassion and for inquisitiveness to be directed toward all those aspects of experience that can never be subjugated or reduced into a particular ideology.

Image 1. Katarina Pirak Sikku Ánná siessá (Aunt Anna), 2014, Courtesy of Polly Yassin and the artist

Image 2. Katarina Pirak Sikku, Badjelántta luottat (Traces from the Land Above), 2013 Courtesy of the Artist

Image 3. From the album Lappar och Lappblandad befolkning, Tillhörande Jokkmokks församl. 1925–1929, Uppsala University Library

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erika Larsson

Erika Larsson obtained her doctorate in Art History and Visual Culture at Lund University, Sweden, in 2018 with a thesis exploring the notion of belonging in contemporary photography from an affective, embodied and non-representational perspective. Today, she has a postdoc position at Valand Academy, Gothenburg University and Hasselblad Foundation, Sweden, researching contemporary photographers’ and artists’ engagements with the interwar period. She also lectures on photography theory and globalisation in relation to visual culture.

Notes

1. In Photographic Engagements, I discuss this archive and contemporary artist’s engagements with it in relation to works that in different ways make use of photographic archives from Ottoman and Turkish history.

2. I use the terms emotional and affective in order to cover both emotions that are already defined as well as bodily phenomena beyond human perception and cognition. According to Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth affect “is the name we give to those forces-visceral forces beneath, alongside, or generally other than conscious knowing, vital forces insisting beyond emotion—that can serve to drive us toward movement, toward thought and extension (…)” (Citation2010, 1).

3. In Dividual-Individual (2017), Finland-Swedish artist Marjo Levlin explores the parts of the archive that contain photographs of the Finnish population in Sweden. In this work, she combines the material with images from a Finnish archive. This latter was the result of research by the Florin Committee in Finland’s Swedish speaking regions. The researchers of this committee were highly influenced by Lundborg and his work.

4. In addition to the field of racial biology, the belief in photographic objectivity was strong in the fields of, for example, medicine, astronomy, botany, and palaeontology. See for example Peter Weingart & Bernd Huppauf, ”Images in and of Science,” 3–32 in Weingart and Huppauf (Citation2012). Reflections on the limitations of photography were carried out by, for example, Siegfried Kracauer in “The Mass Ornament”, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995) (first published in 1927 as Ornament der Masse); Walter Benjamin in “A Short History of Photography”, Screen, 13/1, 1 March 1972, pp. 5–26 (first published in 1931); and Bertolt Brecht in “No insight through photography”, in Brecht on Theatre & Radio (London: Methuen, 2000) (first published in 1930).

5. This brings to mind a list by Ariella Azoulay in which she describes different positions of subjects being photographed in extremely difficult circumstances: “ … the gaze of the photographed subject, which can vary enormously between sharp, probing, passive, exhausted, furious, introverted, defensive, warning, aggressive, full of hatred, pleading, unbalanced, sceptical, cynical, indifferent or demanding”. Here, Azoulay argues against a simplified view of the documented subject as a passive victim. Even in very vulnerable situations, subjects may adopt a range of different positions when they are being photographed.

6. In fact, no archive is a precise systematic documentation, but can rather be understood as performing systematisation and documentation. This is something that many artists have explored in the last years, perhaps most interestingly Walid Ra’ad and the archive of his fictive Atlas Group.

7. Sweden was not the only country to use photography to “map” a country’s racial categories. Germany and the UK had similar projects at that time. However, the research in Sweden was by far the most ambitious of these projects. See Kjellman (Citation2012).

8. In Photographic Engagements, I carry out an extended discussion of the ideologies or modalities that underlie different archives and how artists unfold new understandings from these modalities through their work.

9. Here and throughout the article, the reflections around Pirak Sikku’s own experience come from a conversation with the artist in Uppsala in December 2015.

10. Bildmuseet, “Katarina Pirak Sikku”, interview, 6 February (2014) https://vimeo.com/86000029, accessed 23 November 2016.

11. Katarina Pirak Sikku,“‘Vi var generade över att vara lappar. Det var fult’: Elsas vittnesmål om Rasbiologiska Institutets undersökningar av samiska barn vid Nomadskolan i Vaiki- jaur, Jokkmokk”, symposium recording, 6 May 2016, <https://media.medfarm.uu.se/play/kanal/237>, accessed 15 November 2016.

12. When this work was exhibited in 2015 in Uppsala, the town where the State Institute of Racial Biology used to be and the place where the archive is still kept, two unopened albums from the archive were also included in the exhibition. Both were wrapped in material that Pirak Sikku made from the same warm fabric used for traditional Sámi clothing. One of the albums also had Elsa’s own belt wrapped around it. Taking the albums from the archive and wrapping them in personally hand-made, warm “clothing” here became an act of caring for the documented people.

13. For example, ending the introduction to a collection of photographs of “Swedish Types, Ordered According to Racial Principles”, there is this sentence: “I dare hope that the time will not be too distant when, in social issues, the words of the biologically knowledgeable physician tend to be accorded as much importance as those of, for example, lawyers or crusaders and when, for peoples’ futures, the eyes of more sociologists and statesmen are opened to the importance of hereditary hygiene.” (My translation.) Lundborg (Citation1919).

14. Nussbaum makes a point that these appraisals are not necessarily linguistic or even complex in nature. In fact, she goes to great lengths to describe how some basic forms of judgements are made by animals and give rise to emotions: “All that is required is that the creatures see the object (a bit of food, say) as good from the point of view of the creature’s own pursuits and goals”. Nussbaum (Citation2013, 401).

15. In Dividual-Individual (see note 6), Levlin brings up the feeling of shame in relation to the experience of being documented as Finnish in Sweden. Since the Second World War, a feeling of shame has also come to be connected with the science and the research itself. This explains why it was only at the end of the last century that researchers, artists and others started to look at the material.

16. In some of his letters, Lundborg expressed hopes that the Sámi people would become more compliant and thus make his work easier. He also detailed how one family gave their consent to documentation and how this made him hope that others would follow their lead. From these passages, it is possible to deduce that there was resistance to the research. Nevertheless, there are no stories describing this resistance and what the Sámi felt about the events.

17. For a more extended discussion of Toufic and his reflections about surpassing disasters see Larsson (Citation2018).

18. In addition to Pirak Sikku, others that can be mentioned include Liselott Wajstedt, Anders Sunna, Lena Stenberg, Victoria Andersson and Tomas Colbengtson.

19. Similarly, Christopher Pinney talks about the archival photograph as “a completely textured artifact (concealing many different depths) inviting the viewer to assume many possible different standpoints—both spatial and temporal—in respect to it”.

20. Once again, Lehtola’s words echo Pinney’s observation that “recuperation takes the form of a homecoming: the naming of the formerly anonymous, the individuation and recognition of persons whose work in the archive has usually been to ‘typify’—that is, to exemplify some category”.

21. The photograph can be found in the album Lappar och Lappblandad befolkning, Tillhörande Jokkmokks församl. 1925–1929.

22. In Photographic Belonging, I look at the work of all these artists from an affective theoretical perspective.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. doi:10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

- Azoulay, A. 2008. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York, Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by The MIT Press.

- Bassnett, S. 2009. “Archive and Affect in Contemporary Photography.” Photography and Culture 2 (3, November): 1–10. doi:10.2752/175145109X12532077132239.

- Cvetkovich, A. 2014. “Photographing Objects as Queer Archival Practice.” In Feeling Photography, edited by E. Brown and T. Phu, 273–296. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Edwards, E. 2001. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford, New York: BergBerg.

- Fraser, N. 2013. Fortunes of Feminism: From State-managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis. Brooklyn, New York: Verso Books.

- Gregg, M., and G. J. Seigworth. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press.

- Gregory, E. 2008. Politics and the Order of Love: An Augustinian Ethic of Democratic Citizenship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hagerman, M. 2006. Det Rena Landet: Om Konsten Att Uppfinna Sina Förfäder. Stockholm: Prisma.

- Hansson, H., and J.-E. Lundström. 2008. Looking North: Representations of Sámi in Visual Arts and Literature. Umeå: Bildmuseet, Umeå universitet.

- Keane, A. H. 1886. “The Lapps: Their Origin, Ethnical Affinities, Physical and Mental Characteristics, Usages, Present Status, and Future Prospects.” The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 15: 213. doi:10.2307/2841580.

- Kjellman, U. 2012. “Fysionomi Och Fotografi – Den Rasbiologiska Konstruktionen Av Den Nordiska Rasen Som Vit..” In Om Ras Och Vithet I Det Samtida Sverige, edited by T. Hübinette, et al., 47–69. Tumba: Mångkulturellt centrum.

- Larsson, E. 2018. Photographic Engagements: Belonging and Affective Encounters in Contemporary Photography. Gothenburg: Makadam.

- Lundborg, H. 1919. Svenska Folktyper: Bildgalleri, Ordnat Efter Rasbiologiska Principer Och Försett Med En Orienterande Översikt. Tullberg.

- Nussbaum, M. C. 2013. Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice, viii, 457. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Pinney, C. 2003. “Introduction ‘How The Other Half … ’.” In Photography’s Other Histories, edited by N. Peterson and C. Pinney. Duke University Press.

- Toufic, J. 2009. The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster [online text]. Forthcoming Books. http://www.jalaltoufic.com/downloads/Jalal_Toufic,_The_Withdrawal_of_Tradition_Past_a_Surpassing_Disaster.pdf

- Veli-Pekka, L. 2018. “Our Histories in the Photographs of the Others: Sámi Approaches to Visual Materials in Archives.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, no. 4.

- Weingart, P., and B. Huppauf. 2012. Science Images and Popular Images of the Sciences. Routledge: New York, London.

- Yuval-Davies, N. 2011. The Politics of Belonging; Intersectional Contestations. London: SAGE.