ABSTRACT

Across the world, public spaces are undergoing profound transformations, in tandem with the pluralization processes resulting from several decades of intensified global migration. The aim of this article is to provide some overarching perspectives on the topic of this special issue by examining how artistic and curatorial modes of address contribute to the creation of new public spaces and new forms of publics and assemblies attuned to today’s culturally pluralized and transnationally interconnected societies. The first part outlines how the various roles of art in public spaces (broadly understood) have been defined and evaluated by influential theorists. This account also prepares the way for the focus of the subsequent parts on art’s capacity to intervene into, or alternatively negotiate, social conflicts, and on how this change has gone hand in hand with an increasing artistic and curatorial use of participatory strategies. We then move on to critically discuss this “participatory turn” and explore, by way of a case study of the Maxim Gorki Theatre’s 4. Berliner Herbstsalon (2019), how such practices may permit public spaces to serve as sites of contestation where hegemonic structures and practices are confronted and new forms of collective identification may emerge. We also introduce the concept of postmigrant public spaces to more accurately describe the conflict-negotiating and coalition-building role that art is increasingly called upon to fulfil in the public spaces of today’s culturally diverse “societies of negotiation” (Foroutan).

I am not arguing that, as critics, we should surrender our scepticism or our willingness to situate specific practices in a larger political context, but I do think we have to consider the possibility that our own a priori assumptions about the nature of political change and revolution might need to be revised in the light of new, unfolding forms of resistance and activist practice today … the very generative processes of resistance specific to our time, out of which new configurations of the political will, and must, evolve. (Kester Citation2017, 95)

The turn to the social and the political

The biennial is an event format widely used for mega-exhibitions of contemporary art, whereas the festival is the preferred large-scale event format in the world of theatre and film. It is thus all the more remarkable that, in 2013, Shermin Langhoff, the then newly appointed Artistic Director of the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, and her new ensemble, took the pioneering decision to open with a biennial—or Herbstsalon, as Langhoff named it—that provided platforms first and foremost to visual and performance artists (Langhoff Citation2020, 471). Now numbering four editions, the Berliner Herbstsalon has become a ground-breaking forum for the interweaving of curatorial, artistic, performative, activist and academic practices. It has developed into a politicized space where new alliances can be forged between a diverse crowd of people who represent different political positionalities and varying types of professional expertise and life experience.

On 25 October 2019, the Maxim Gorki Theatre opened its 4. Berliner Herbstsalon under a headline that also served as a political battle cry: DE-HEIMATIZE IT! Borrowed from a lecture by sociologist Bilgin Ayata, the title could be seen as a postmigrant, feminist and localized variation on the now globalized call to “decolonize” hegemonic Western power structures and modes of thinking. The curatorial scenography of what we would describe as the visual “opening act” of the fourth salon is especially interesting to look at in the context of this special issue on art in public space. This opening act staged works of art in the public square in front of the theatre and in the entrance hall that leads to the theatre’s foyer, thereby transforming the square and the hall into a kind of public stage. In order to access the theatre, approaching visitors had to enter this stage designed to entice them to engage emotionally and intellectually with the works they encountered on their way, in the same manner that a piece of installation art invites the viewer-participant who moves about in the work’s scenographical space to engage with the different components of the work and interpret them as a communicative whole, despite the installation’s composite visual appearance.Footnote1

Using the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon as an entry point, the purpose of this article is to unpack some overarching perspectives on the topic of this special issue: the changing roles of art in public space. It examines how artistic and curatorial modes of address contribute to the creation of new public spaces and new forms of publics and assemblies attuned to today’s culturally pluralized and transnationally interconnected societies. The first part outlines how the various roles of art in public spaces (broadly defined) have been discussed and evaluated by influential theorists. This account also prepares the way for the focus of the subsequent parts on art’s capacity to intervene into, or, alternatively, negotiate, social conflicts, and how this change has gone hand in hand with an increasing artistic and curatorial use of participatory strategies ranging from the ameliorative to the agitational. We then move on to critically discuss this “participatory turn” and explore—in a case study of the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon—how such practices may permit public spaces to serve as sites of contestation where hegemonic structures and practices are confronted and new forms of collective identification may emerge.

It is in line with the general theme of this special issue that we focus on a European example. However, we hope that it will provide insights to address other contexts. As two of the leading experts in the field, Claire Bishop and Grant H. Kester, have argued, it should be noted that the orientation towards social contexts and participatory and collaborative practices has become “a near global phenomenon” (Bishop Citation2012, 2) that suggests “the global emergence of a new paradigm of artistic production” (Kester Citation2011, 213). Notwithstanding their global reach, participatory practices have flourished “most intensively in European countries with a strong tradition of public funding for the arts”, explains Bishop. Also relevant to this special issue is Bishop’s observation (Citation2012, 2) that such practices figure prominently “in the public sector”, whereas they have failed to gain a foothold in the commercial art world with its preference for works of art as portable, commodifiable products rather than as evanescent social situations.

In connection with our discussion of participation, we introduce the concept of postmigrant public spaces to more accurately describe the conflict-negotiating and coalition-building roles that art is increasingly called upon to fulfil in the public spaces of today’s culturally diverse “societies of negotiation” (Foroutan et al. Citation2015, 74; see also: Foroutan Citation2019, 60). In contrast to the notion of the nation as a public sphere, the designator postmigrant does not draw imaginary national borders around a public, but emphasizes the transcultural entanglements resulting from migration. The concept of postmigration (das Postmigrantische) is itself a recent addition to the critical vocabulary of the humanities and the social sciences that refers to the “after” (post-) effects of migration on society, not population movements as such.Footnote2 Around 2010, the concept was extrapolated from the cultural debates about so-called postmigrant theatre in Germany, which had emerged a few years earlier from the intellectual and artistic environment around the Ballhaus Naunynstraße theatre in Berlin’s Kreuzberg district. Ballhaus Naunynstraße was founded in 2008 by the aforementioned Shermin Langhoff, who made significant contributions to establishing the concept of postmigrant theatre since she used it to label the new kind of stories and productions that were created at the theatre. As our case study below indicates, Langhoff has continued to develop her postmigratory agenda after she moved to the Maxim Gorki Theatre in 2013.

Art’s roles in public spaces—old and new

The political theorist Chantal Mouffe has argued that, in a pluralist democracy, a fully functional public space has to be able to accept antagonisms, since it is created through the constant negotiation and renegotiation of different, often antagonistic, positions. According to Mouffe’s reflections on pluralist democracy, a public space is not a space of consensus but a field of negotiation where different hegemonic projects wrestle with each other without the possibility of reaching a definitive, rational and fully inclusive consensus. Art in public spaces is thus assigned the role of inciting dissent, making visible what the dominant discourses tend to obscure and obliterate, and constructing new points of collective identification (Mouffe Citation2007a). As the social scientist Naika Foroutan has observed, “migration” has become one of these dominant discourses, a magnet for political, media and popular attention and anxieties. As a result, many of the conflicts at the heart of plural democratic societies—such as the struggles for equality, freedom, security and democratic rights—are fought, in an emblematic way, in relation to migration (Foroutan Citation2019, 31). This is one of the reasons why the political salience of migration has increased despite the relative stability of migration rates since the 1970s, as observed by Haas, Castles and Miller (Citation2020, 1). It is also one of the reasons, we submit, why it is paramount to explore the ways in which public art projects grapple with migration-related issues (as reflective of key conflicts in society), and how they intervene critically in the dominant public discourses and seek to develop new forms of democratic participation.

As the theatre and performance studies scholar Sruti Bala has noted, the theorization of participation in the arts necessitates the translation of a concept with roots in the spheres of economics and politics to “imaginative terrains”. In our theoretical discussion of participation below, we will adopt Bala’s broad translation of the term to fit the arts to indicate primarily “a realignment of the relationship between the makers and the recipients of the arts, whereby the ‘recipients’, however defined, stake a claim to or assume a share in the enterprise of the arts” (Citation2018, 5). In the spheres of art institutional and cultural politics, this notion is further undergirded by the widespread assumption that this realignment—or as Bishop would have it, this “gesture of reducing authorship to the role of facilitation” (Citation2012, 21) by which “art enters a realm of useful ameliorative and ultimately modest gestures” (23)—is desirable for the arts and the social and institutional contexts in which they operate.

The spread of participatory practices is an integral part of a more encompassing transformation of art in public spaces. The term public art first emerged in the USA in the late 1960s in conjunction with the introduction of national and municipal art patronage for the creation of sculptures and murals for parks, squares and other nominally public places. Oftentimes, these permanently installed object-based works were, and still are, “integrated with urban planning or ‘revitalization’ schemes” and are thus connected to urban history and a tradition of commemorative sculpture and mural painting that extends back to antiquity (Kester Citation2011, 186–187). Since the 1960s, public art has assumed a range of new roles. The proverbial “public sculpture” embellishing the city square has long since developed into an expanded field that comprises both physical and media spaces, thereby transforming the art object in public space into a wide-ranging “expanded field” (Krauss Citation1987). As early as 2002, art historian Miwon Kwon made the perceptive observation that three “paradigms” may synthesize the evolutionary arch of public art since the 1960s: the art-in-public-places exemplified by nonfigurative modernist sculptures; the art-as-public-spaces approach typified by design-oriented sculpture serving as street furniture, architectural constructions or landscaped environments; and art-in-the-public-interest, a term coined by critic Arlene Raven to describe projects that foreground social issues, political activism and sometimes also community collaboration. The latter was also theorized by the artist Suzanne Lacy under the perhaps more well-known heading of “new genre public art” (Kwon Citation2002, 60; Lacy Citation1995).

Even so, the twenty-first century has seen the emergence of numerous aesthetic transformations and different socially and politically oriented ramifications of the third category. The richness of the field means it is virtually impossible to give a survey of art in public spaces, although the Skulptur Projekte in Münster has endeavoured to do so at intervals of a decade. Covering the decisive timespan from 1977 to 2017, this series of mega-exhibitions of art in public spaces testifies to a general move from “public sculpture” to “art as social practice”.Footnote3 The same observation applies to the scholarly research and critical theories on public art, socially engaged community art and politically engaged art activism. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide an exhaustive review of the multi-disciplinary and ever-expanding body of literature on art in public spaces. We find it more relevant to trace the recent discussions against the background of existing knowledge.Footnote4 In the following, we will thus use the very problem of delineating the empirical field and the discourse of “art in public spaces” as a spur to examine some of the conceptual nodal points around which the discussions have revolved in recent decades.

We would like to suggest that the problem of defining art in public spaces is, in fact, twofold, in the sense that it exists on two distinct levels—that of discourse and that of practice, with each presenting its own problems of delineation. On the discursive level, the problem concerns the entanglement of the discourses on and concepts of public art, public space, the public sphere, and publics. A distinction must be made between these terms, despite the fact that they tend to bleed into each other and cannot be neatly disentangled. We draw on communications scholar Slavko Splichal’s distinction between a public sphere and a public, according to which a public is “a social category, whose members (discursively) act, form, and express opinions” and a public sphere is “its infrastructure” comprising various “channels of opinion-circulation” (Citation2010, 28). As Splichal explains, “A public sphere cannot act, it cannot communicate, but a/the public can. The public sphere is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a/the public to emerge, an infrastructure that enables the formation of the public as the subject, the bearer of public opinion” (28). Our understanding of a/the public is based on queer and literary theorist Michael Warner’s understanding of a public as “a special kind of virtual social object enabling a special mode of address” (Citation2005, 55) and his argument that a public “exists by virtue of being addressed” (67). We also adopt Warner’s definition of a counterpublic as a public whose discussions are “being structured by alternative dispositions, making different assumptions about what can be said or what goes without saying. [… P]articipation in such a public is one of the ways by which its members’ identities are formed and transformed.” (Citation2005, 56–57) As regards the public(s) addressed by art in public spaces, it is important to stress that the extent of a public, and also of a counterpublic, is not delineated by “a precise demographic” like a subculture. It is “in principle indefinite” since it is generated by the way in which the public address is “mediated” (Warner Citation2005, 56), in our case by the artwork’s address to the many different kinds of people who may respond (or not) in different and sometimes incompatible ways.

Since publics are not coterminous with public spaces, we suggest that they are best understood to be the malleable formations of participants that exist, and coexist, within these civic domains of human encounter. Furthermore, we understand postmigrant public spaces to be plural and conflictual domains of human encounter that have, in various ways and to different degrees, been configured by transnational mobility, and by the social transformations and the changes to domestic demography and civic consciousness that immigration has brought about. In their capacity as public spaces, they can accommodate multiple (counter)publics, even though they are arguably regulated by mechanisms of exclusion that distribute the “access” to participation unequally. For this reason, they tend towards conflictual plurality rather than towards an imaginary Habermasian ideal of unifying consensus.Footnote5

The second problem of delineation exists on the level of practice. The invention of new roles for art and curating in public spaces in recent decades has not only expanded the range of artistic approaches to public space significantly but has also had other intended, as well as unintended, effects. Some of the most conspicuous effects are the blurring of the boundaries between artistic, curatorial and social practices, and the merging of the domain of art with that of politics. The breakdown of these boundaries is closely linked to the introduction of a broad range of participatory practices, and, on the level of theory, to the critical debate on their potential for social amelioration and political agitation, or lack thereof. In the following, we will explore some of the new “social” and “political” roles for art and curating in public spaces, based on some significant contributions to the scholarly literature.Footnote6

The institutionalization of socially engaged art

The dissolution of the distinction between artistic, curatorial and social practices has followed from a progressive shift in artistic approaches to public art—from mainly producing spatially delimited “public sculptures” to generating “social spaces”. This approach often involves orchestrating distributed, participatory “social processes”, which draw on educational formats as well as the ways in which feminist artists of the 1960s and 1970s opened the exhibition format to new working methods drawn from everyday culture and an experimental practice that emphasized “the formation of new publics and a collectively developed, embodied knowledge” (von Osten Citation2011, 63). With the spread of transdisciplinary, theme-related “project exhibitions” in the mid-1980s, the feminist methods were complemented by antiracist approaches and openings for minoritized groups “that had previously had no access to that space” (von Osten Citation2011, 63–64).

Despite the dramatic diversification of the field since the mid-1980s, the core idea of public art that people should be able to access art in their everyday lives has remained intact. So has the widespread belief among art professionals in the Enlightenment promise that the experience of art can prepare the viewer to become “a more effective participant in public, political discourse”, as Kester observes in The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context. In this seminal study of the integration, and at times collision, between community collaboration, artistic production and political activism in contemporary collaborative art, Kester discusses how and to what extent socio-political public art succeeds in establishing a collaborative relationship with the participants (Citation2011, 187, 190; see also: Cartiere Citation2013, 132). As he rightly points out, the abstract public art that dominated the 1960s and 1970s was often met with hostility. By the late 1980s, the controversies would generate a broad rethinking of the methods, functions and objectives of public art, including art’s relationship to the social and its political potential. This reconsideration contributed to paving the way not only for the incorporation of public art genres into speculative real estate development and gentrification processes but also for the emergence of new forms of community art and socially engaged art and their subsequent institutionalization (Kester Citation2011, 191–197). Lastly, but importantly, the artistic orientation towards the social also reorganized the relationship between the art object, the artist and the audience. Bishop has described the transformation of their roles accurately, noting that “the artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations; the work of art as a finite, portable, commodifiable product is reconceived as an ongoing or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a ‘viewer’ or ‘beholder’ is now repositioned as co-producer or participant” (Citation2012, 2).

One aspect of the institutionalization of socially engaged art is the new centrality of curators, or, rather, of “the curatorial function”. Political theorist Oliver Marchart has introduced this term to shift the focus from the individual curator to the public, participatory and political dimensions of art. According to Marchart, an exhibition must be a place for debate; hence, “the curatorial function lies in the organization of the public sphere” (Citation2007, 43). For such a public sphere to be truly political, the exhibition must mark or establish “a position” to initiate the breakdown of consensus that is needed to enable conflicting or “antagonistic” viewpoints to emerge (45). Marchart’s concept of the curatorial function can be linked to an increasing emphasis on the discursive in the art world. In their introduction to the anthology Curating and the Educational Turn, the editors Paul O’Neill and Mick Wilson suggest that the shift of emphasis toward the discursive since the mid-1990s has engendered a new “turn” in which curatorial and artistic practices are increasingly amalgamated with informal forms of education. They observe a growing tendency to make discursive interventions such as discussions, talks and symposia “the main event”, and to frame this in terms of research, knowledge production and learning. What we see here is not a mere “reinstatement of the curator as expert” but “a kind of ‘curatorialisation’ of education whereby the educative process often becomes the object of curatorial production” (O’Neill and Wilson Citation2010, 12–13). Crucially, in our context, such informal educational formats, discursive productions and forms of self-organization are “public” in the sense that they are generative of (counter)publics and public spaces. Furthermore, as they are deployed as much by curators as by artists and other cultural producers, it makes no sense to maintain a strict categorical division between artistic and curatorial practitioners within this sphere of cultural practices based on collaborative structures and the organization of socially oriented forms of co-production (O’Neill and Wilson Citation2010, 19).Footnote7 The concepts of the curatorial function and curatorialization are accurate theoretical markers of this interdisciplinary “discursive” trend.

Although the concept of participatory art has caught on in the global art world, it is nevertheless contested. Claire Bishop has famously argued that participatory art is put in the service of neoliberal social inclusion policies that are “less about repairing the social bond than a mission to enable all members of society to be self-administering fully functioning consumers” (Citation2012, 14).Footnote8 In contrast, Kester (Citation2017, 83–85) is adamant that socially engaged art can contribute to individual, cultural, social and political change, even if it does not have the power to initiate a full-scale revolution of society or the downfall of the pervasive capitalist system. Kester conceives art’s potential for change as “a mode of capillary action” that runs in roundabout and improvisational ways, from individual consciousness to collective action and resistance. It is thus a process that is compromised because it emerges out of pre-existing material, discursive and (counter)institutional practices. It is imperfect and messy as it “involves the emergence of new solidarities, and their subsequent dissolution, moments of improvisational consensus, and moments of dissensus” (Kester Citation2017, 83–84), but as Kester suggests in the epigraph to our article, they also represent “the very generative processes of resistance specific to our time, out of which new configurations of the political will, and must, evolve” (95). As the opposing positions of Bishop and Kester indicate, the concept of participation is key to contemporary debates on the efficacy of socially and politically engaged art, so we will return to it below after we have factored in the politicization of art in public spaces that has accompanied the turn to the social.

Art engaging politics: conflictual aesthetics

The entanglement of art and politics—that is, of art practices and political engagement—is seen most conspicuously in art activism, or “artivism”, as perhaps the most radical expression of a more pervasive tendency in contemporary art to address viewers primarily as a collective, social community with agency (rather than as contemplative individuals), and to consider art to be a potential trigger for politicized action.Footnote9 As the cultural studies scholar Camilla Møhring Reestorff has pointed out, art practices can be artivism without the artist self-identifying as such. Essentially, the term refers to the use of artistic means of expression “to participate in political dialogue and engage in mobile publics that navigate and criss-cross between three publics: institutional, non-institutional and mediatized art publics” (Reestorff Citation2017, 16). More often than not, artivism is designed to produce friction and instigate debate in some kind of public arena (including online platforms and other media) where it often gains a certain political efficacy because such spaces are always already fraught with different, often conflicting, political and social interests in the area of concern precisely because they are “public”.

Turning from the level of practice back to that of discourse, a pertinent place to start is Claire Bishop’s agenda-setting 2004 study of the different political inflections of socially engaged art. Bishop contrasts the consensus-oriented relational aesthetics epitomized by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Liam Gillick with the antagonistic interventionist approaches of Santiago Sierra and Thomas Hirschhorn (Bishop Citation2004, 68). Bishop’s study not only brought Chantal Mouffe’s twin concepts of antagonism and agonism to the centre of the theorization of art and politics, but what is important to our study is the fact that Bishop also moved the question of migration to the forefront—as in her analyses of Sierra’s projects with subaltern irregular immigrants, such as his collaboration with African street vendors in the project Persons Paid to Have Their Hair Dyed Blond for the Venice Biennial and the canal city’s urban spaces (2001), and of Hirschhorn’s Bataille Monument for Documenta XI, Kassel (2002). The latter consisted of a cluster of makeshift pavilions and sculptures built in collaboration with and installed in the midst of an ethnically mixed suburban community whose economic status did not match that of the art audience. Although the migratory thematic is usually bypassed by commentators, Bishop’s analyses opened the discussion of the place of migrants and issues of migration in the usually nationally circumscribed frameworks of public art.

Western theorizations of the relations between art, aesthetics and politics in the twenty-first century have been much influenced by the philosopher Jacques Rancière, whose theories are widely read as a new approach to political aesthetics (Citation2004, Citation2009, Citation2010). His ideas are often compared to, or even amalgamated with, that of Chantal Mouffe because they both denounce the Habermasian belief in the possibility of reaching consensus, and emphasise that conflict and disagreement—or in Mouffe’s terms, antagonism and agonism—are preconditions for the ongoing struggles at the core of an open, radical form of democracy and cultural citizenship.Footnote10 Furthermore, they both work from the a priori assumption of art’s overall politicality; as artistic and other aesthetic practices play a part in the constitution of the symbolic structures of society, they cannot be separated from the political. This is especially true of art in public spaces. The theory of hegemony and radical democracy that Mouffe developed together with Ernesto Laclau (Laclau and Mouffe Citation2001), and Mouffe’s own essays on art in public spaces and the connection between artivism and political theory, have introduced a productive theoretical vocabulary to analyse art’s methods of disruption and stirring up dissension (Citation2005, Citation2007a, Citationb). In her essays, Mouffe tends to distinguish between three dimensions, of which the first has to do with art’s profound politicality, its inseparability from the political. The second concerns the criticality of art, and the third actual artivism, i.e. the practices of artists who abandon conventional artistic media and art institutions to adopt strategies of political activism and politicized modes of expression. As Oliver Marchart concludes, “for Mouffe all art is political, but only some art is critical, and only some critical art is activist art” (Citation2019, 24). Marchart, whose theory we draw on below, has criticized Rancière’s theory for being “antipolitical” because it provides the art field with a “cover up” consisting of “ideological arguments against any explicit politicization” (14).Footnote11 Instead, Marchart uses Mouffe’s twin concepts of antagonism and agonism to develop his own theory of conflictual aesthetics and “push the argument even further” (25) by insisting on the need to shift the emphasis from negotiation to conflict as necessary components of democratic processes, thereby “reantagonizing antagonisms” (27).

Marchart has aptly described art’s methods of political disruption as strategies of agitation. Together with acts of “propagating” and “organizing”, agitating constitutes what Marchart terms conflictual aesthetics. The term refers to how artists use aesthetic and activist means to respond to, or contribute to, social justice movements. It denotes an aesthetics that is ontologically grounded in antagonism, and which is “conflictual in a double sense […], both a conflicting aesthetics and an aesthetics of conflict” (Citation2019, 23, see also 26 and 30). By using strategies of propagation, agitation and organisation, artists can help create “new social and political antagonisms in the global struggle for justice” (Danbolt Citation2020). Although Marchart mainly associates conflictual aesthetics with political movements such as the Occupy Movement (2011–2012) and with art activism (which often has close links to extra-institutional forms of political activism), he does acknowledge that institutions are “potentially powerful counterhegemonic machines” that may afford some leeway for “the construction of counterhegemony” (Marchart Citation2019, 25–26). His theory of conflictual aesthetics thus offers a productive framework for our case study of the Maxim Gorki Theatre’s 4. Berliner Herbstsalon, with its radical breakdown of the boundaries between various institutions. The radicality of the Gorki Theatre’s agitational strategies of generating counterpublics becomes more apparent when they are measured against the ameliorative strategies that tend to dominate participatory art.

The contested term of participation

Over the last decades, cultural institutions active in the planning of public art have, to a still increasing degree, employed participatory strategies in relation to practices of art, education and mediation. In this way, they have sought to address issues such as community cohesion and social inclusion, in addition to engaging diverse groups that are perceived as marginalized in some respect. The claim for engagement, inclusion and stimulation of social relations has clearly become a predominant feature of art presented both within and beyond traditional art institutional contexts. When encountering artistic and curatorial projects, the visitor is often positioned as a “user” and a “participant”, and a “co-creator” of content—for example, when being invited to express one’s opinion by commenting on, rating and evaluating projects, when taking any active part in exhibition-related activities, or when being engaged in experimental and participatory formats of mediation specifically aimed at audience involvement. Within the field of art, participation as a strategy has thus become pervasive to the extent that it has been described as sine qua non for contemporary art productions and art institutional practices (Bolt et al. Citation2014, 5). However, the ways in which participation is viewed, analysed and evaluated tend to vary.

Within museum studies, for example, theorists such as George Hein, Nina Simons, John Falk and Lynn Dierking have argued that, as a strategy and practice, participation appears key if art institutions are to legitimize their relevance and value in relation to their audiences (Hein Citation1998; Simon Citation2010; Falk and Dierking Citation2013). Following this line of thinking, participation is viewed as a positive means of creating more inclusive institutions and developing new and more diversified audiences, as well as of experimenting with educational and outreach strategies that focus on user involvement, situational learning and dialogical forms of mediation. Within art discourse, participation has likewise become a central matter of concern during the last decades. For example, in the discourses rooted in relational aesthetics, socially engaged art and new genre public art theorists such as Nicolas Bourriaud, Grant Kester, Suzanne Lacy and Mary Jane Jacob have analysed and discussed the ameliorative potentials of participatory practices. From different perspectives and varying vantage points, they have focused attention specifically on art’s ability to stage intersubjective encounters, to contribute to the creation of actively involved publics and lay the ground for collective action and community-building (Bourriaud Citation1998; Kester Citation2011; Lacy Citation1995; Jacob Citation1995).

According to these discourses on socially engaged art, participation is widely acknowledged as a means to transform passive art audiences into active users and co-producers. Therefore, it is evaluated positively and viewed as a tool that can facilitate intersubjective encounters, strengthen social ties and contribute actively to community building. Shifting attention from anonymous art audiences to specific publics—often in the form of non-white, working class or generally poorer sections of the population, conflict-ridden communities or war-torn societies—advocates of socially engaged art who focus on the ameliorative potentials of participatory activity argue that art practices can play an important role by seeking to integrate friction-filled communities through creative processes and reconcile otherwise segregated social spheres. Furthermore, within museum discourse, participation is perceived as an effective means to stimulate a sense of access, ownership and agency among the visitor-participants, so as to contribute to a more open, egalitarian and democratic development of art and its institutions. However, as several more critically inclined theorists have pointed out, participatory strategies and design techniques often tend to be both calculating, predictable and prescriptive (Sternfeld Citation2013; Bishop Citation2012; Raunig Citation2013). The ideal of participation as an inclusive, empowering and democratically engaging strategy per se has been critically discussed, for example, in Claire Bishop’s seminal publication Artificial Hells, as well as in the architect and design theorist Marcus Miessen’s The Nightmare of Participation (Bishop Citation2012; Miessen Citation2010). As the titles of these publications indicate, they apply a sceptical approach to today’s prevalent paradigm of participation.

Bishop defines participatory art as practices that are oriented towards social and political realities and which reposition the audience, previously conceived as a “viewer” or “beholder”, as a co-producer or participant. As mentioned above, Bishop is far from uncritical of this kind of art practice and the power ascribed to it. Taking her point of departure in Nicolas Bourriaud’s reflections on relational aesthetics, she argues that participatory practices, often against the artists’ and curators’ stated intentions, end up staging art as an elitist and self-referential discussion for those already in the know and familiar with the art discourse. In this way, participatory art can be said to address “a community of viewing subjects with something in common” (Bishop Citation2004, 68), i.e. as a social congregation free of friction, thus reproducing and affirming existing social hierarchies instead of contesting them.

Markus Miessen, through conducting practice-based research into contemporary artistic, architectural and educational practices realized in urban public spaces, has articulated a more explicitly political critique of the participatory paradigm, countering the perception of participation as inherently inclusive and the idea that everyone is equal in the process. He argues that participatory processes often tend to affirm the asymmetrical power relations that characterize today’s capitalist societies, when artists, architects and other cultural producers accept existing power structures because they believe that they can be altered from an internal position. Miessen suggests that the ameliorative and consensus-seeking approach to participation—or that which he polemically terms “pseudo-participation”—must be substituted by a conflict-oriented one (Citation2010: 120). Drawing upon the radical democracy theories of Chantal Mouffe and her reflections on the potential of the so-called agonistic model, Miessen emphasizes the necessity of conflict in order to instigate political confrontation and bring about real societal change. In doing so, he takes a stance similar to that of Oliver Marchart. Miessen also pinpoints the crucial role that the involved outsider plays when intervening critically in order to instigate such conflicts. As Mouffe has argued, Miessen has a tendency to overemphasize and essentialize the notion of the outsider.Footnote12 According to Miessen, however, the involved outsider allows architecture and other spatial practices—such as, one might add in this specific context, art in public spaces—to give form to this new modus operandi and create the necessary conditions for radical political changes to take place.

The consensus-oriented perception of participation as being equated with advocacy and equality has also been convincingly confronted by Nora Sternfeld. From the point of view of a curatorial perspective, Sternfeld argues that participants in contemporary artistic and curatorial projects are often placed in predefined positions without any possibility of acting on their own terms. In her seminal article “The Rules of the Game: Participation in the Post-Representative Museum”, Sternfeld notes that participation is often reduced to interaction, as those involved are given “the impression that they are participating, yet without their participation having any influence whatsoever” (Citation2013: 2). In other words, Sternfeld argues that those invited to take part simply join the already planned and choreographed activities, rather than being provided with the possibility of critically questioning the rules of the game, i.e. the conditions under which the artistic and curatorial activities take place within the art institutional frameworks (4).

Sternfeld launches a harsh and somewhat generalizing criticism when envisioning the participatory agenda characterizing the majority of today’s artistic and curatorial practices as defined by strategies that merely affirm the existing hegemonic power structures. However, we agree that experimenting with radicalized notions of participation requires a critical rethinking of the epistemological foundations of exhibitions and their terms of production and mediation of artistic and curatorial practices. Although we will argue for the importance of differentiating and contextualizing when discussing the notion of participation in relation to concrete curatorial practices, we concur with the view that participatory projects can never simply operate as well-meaning gestures to activate audience groups but need to be aware, rather, of their own assumptions and lack of knowledge.

Importantly in this specific context, advocating for a radicalized and politicized approach to participation, Sternfeld proposes to act in accordance with the idea of “post-identitary solidarity”. This would entail working with collective practices that seek to negotiate existing power relations, that resist minority ascriptions in the fixed form of essentialized identities and which take a political stance, acting “in solidarity with the disturbance that takes place when what Rancière calls ‘the part that has no part’ disrupts the police logic” (Sternfeld Citation2013, 6). Radicalized forms of participation are thus seen as a means to promote modes of alternative sociability that struggle for equality and the self-ascription of identities, as well as “for hegemony, for power, for distribution and for expropriating the existing power relations within the field of visibility” (Sternfeld Citation2013, 4). Importantly, according to Sternfeld, social formations such as these allow space for conflict and disagreement in order to uncover the difficulties at play when dealing with contentious positionalities, and they enable the creation of politically mobilizing alliances of solidarity between people that are not guaranteed of a social group or community by the pre-existing form. In summary, a common denominator of the conflict-oriented perspectives on participation discussed here is the need to reflect critically on the concept. Agreeing with this point, we will argue that it is important to always consider who is participating and in what way, which identity ascriptions are part of the game, and how power is distributed and negotiated among those involved.

The postmigrant public space of 4. Berliner Herbstsalon

An important aspect of the debates on the politicization of art in public spaces and the mobilization of viewer-participant agency is the vexed issue of the political efficacy of art. Any serious consideration of this issue should seek to avoid easy generalizations and instead try to strike a balance and steer clear of two common pitfalls: on the one hand, there is the popular disbelief in art’s potential to change anything in “the real world”, and, on the other, the naïve endorsement of art’s revolutionary power by some diehard idealists of the art world. As Marchart has convincingly argued, it is impossible to foretell the long-term effects of political protest. He offers an eye-opening comparison of political art with historical political revolutions. The revolutions of 1848, observes Marchart, initially failed (except in Switzerland), and yet the real significance of 1848 did not come into full effect until decades later with the formation of democracies across Europe, and, more than a century later, with the anticolonial independence movements in former colonies. A similar pattern of societal transformation as “a mode of capillary action”, as Kester (Citation2017, 83–84) would call it, can be observed in the cultural field. While the short-term effects of the 1968 revolts were “less than impressive”, a long-term perspective reveals that “more than a political revolution, ’68 was a cultural revolution that had begun to modify our whole way of life” (Marchart Citation2019, 10). On this hopeful note, we now shift attention from the level of discourse back to that of practice and turn to our case study of the Maxim Gorki Theatre’s 4. Berliner Herbstsalon, with its transgressions of the boundaries between various institutions and disciplines, its critical interrogation of traditional notions of national belonging and its call for radical forms of coalition building in the name of solidarity.,,,,

Figure 1. View of the square in front of the Maxim Gorki Theatre seen from the theatre’s staircase in October 2019. to the right, the venue Gorki Container with the title of the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon, DE-HEIMATIZE IT! Written on the wall; in the centre of the square, Regina José Galindo’s installation No violarás (“Thou shall not rape!”). Photo: Anne Ring Petersen

Figure 2. Atom Egoyan Auroras (2007). To reach the Gorki Container and the Maxim Gorki Theatre, visitors would have to walk along Egoyan’s video installation in which seven “Auroras” recite texts from the book Ravished Armenia by Aurora Mardiganian, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide in 1915. Photo: Anne Ring Petersen

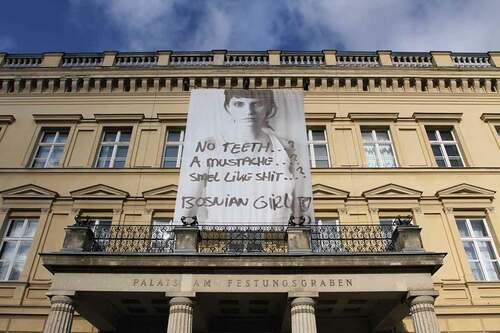

Figure 3. Šejla Kamerić’s photographic banner Bosnian Girl (2003) installed above the entrance to Palais am Festungsgraben, the main venue of the art exhibition of the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon (2019). © Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin. Photo: Lutz Knospe

Figure 4. Regina José Galindo’s installation No violarás (Du sollst nicht vergewaltigen) (“You shall not rape!”), 2013. Photo: Lutz Knospe

Figure 5. Marta Górnicka, Grundgesetz. Ein Chorischer Stresstest. Production of the Maxim Gorki Theatre. Dual screen video installation documenting the chorus performance in front of the Brandenburger Tor on 3 October 2018. Displayed in the entrance hall of the Maxim Gorki Theatre during the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon, 2019. photo: Anne Ring Petersen

In keeping with the tradition from the previous editions of Gorki’s Herbstsalon, the fourth biennial in 2019 combined a theatre and performance festival with an exhibition of contemporary art and an academic conference. In addition, the fourth salon also comprised the Young Curators Academy, a workshop that provided a framework for young, politically engaged curators. As Langhoff has explained, the idea was to bring together “artists, activists, theoreticians and theatre makers from all over the world” to encourage the creation of “a language that is not nationalist and racist, not male dominated and sexist, and not beholden to the arithmetic of the market and economic utilisation” (Citation2020, 486).

Passing the Humboldt Universität at Unter den Linden and walking on past the Neue Wache, from where call-up orders for the First World War were sent in 1914 (Langhoff Citation2020, 468), visitors to the Gorki Theatre were subtly guided on a tour through the espalier of Prussian chestnut trees where they encountered the Gorki’s bright orange banner with the mobilising call of the Herbstsalon to “DE-HEIMATIZE IT!”. From here the itinerary led to Am Festungsgraben, with the entrance to the Gorki Theatre as the vanishing point at the end of the rectangular square, flanked on the left by the more intimate venue Gorki Container, and on the right by the Palais am Festungsgraben—the main venue of the art exhibition.

Crossing the square, visitors would have initially encountered Atom Egoyan’s video installation Auroras (2007), with its re-enactions of female eyewitness accounts of the murderous violation of women by nationalist Turkish soldiers during the Armenian Genocide in 1915. Almost simultaneously, the façade of the Palais am Festungsgraben, with Šejla Kamerić’s banner Bosnian Girl picking up on the theme of violent abuse, might have entered the visitor’s mobile field of vision from the right. Here, the artist depicted herself in the style of fashion magazines, but with more recent misogynist and racist hate speech superimposed on her body: “No teeth … ? A mustache … ? Smell like shit … ? Bosnian girl!” These words, scribbled by a Dutch soldier on a barrack wall near Srebrenica in 1994/95, stir up the ghosts of the Yugoslav Wars and specifically the genocide at Srebrenica, which the presence of the United Nations Protection Force failed to prevent (Begrich et al. Citation2019, 7).

Below Kamerić’s banner, the visitor’s eye could dwell on the handwritten protest signs that crowned the makeshift spatial extension of Nina Ender and Stefan Kolosko’s installation and performance Lebensdorn Heilanstalten Haus 2 inside the exhibition venue, one sign seemingly commenting on the historical root and cause of the abusive remark in Kamerić’s Bosnian Girl: It’s “Patriarchatsmüll”, i.e. “patriarchal rubbish”. Before reaching the theatre entrance, visitors would have passed between a repetition of the salon’s agitational call for de-heimatization, painted in huge capitals onto the wall of the Gorki Container, and Regina José Galindo’s cubic light box installation No Violarás (Du sollst nicht vergewaltigen) (2013), which also put out a protest message in the imperative. Like “DEHEIMATIZE IT!, the light box inscription “You shall not rape!” served as a kind of ethical commentary on Auroras and Bosnian Girl, and as an invitation to learn from history instead of silencing it.

Finally, inside the entrance hall, visitors encountered a dual screen video documentation of Marta Górnicka and Gorki’s chorus theatre production Grundgesetz (“Constitution”, 2018). Using a libretto based on the German Constitution, and a stage in front of the Brandenburger Tor, Górnicka’s extraordinary chorus, composed of a diverse spectrum of citizens, explored the resilience and limits of the legal text in the context of the political tensions in postmigrant German society. Importantly, in our context, Grundgesetz was installed with one screen on either side of the central door to the theatre foyer (and the mainstage), thereby providing a kind of “conclusion” to the Herbstsalon’s visual opening act and forming a symbolic portal to the next “act” by gesturing towards a radically plural democracy.

The visual opening act used art to insert visitors as mobile bodies on the Gorki Theatre’s public stage, and to act as a mediator for the organizers’ public address. The visitors were addressed or interpellated as political subjects by the mobilizing instruction to “de-heimatize it” and by the messages of the artworks. The visual opening act thus created not only an art audience but also a public for a political mode of address. Not only did the theatre stage the visitor’s itinerary to effectively communicate a feminist critique of violence, rape and misogyny—resonating with the activist politics of the #MeToo movement—but also to introduce the agenda of de-heimatization, thereby foregrounding the profoundly postmigrant character of the Gorki Theatre and the Herbstsalon as public spaces.

The visual overture thus prepared the audience for the fourth salon’s attack against the venerable German notion of “homeplace and belonging” captured in the word Heimat which is so central to traditional German narratives of national and regional belonging. The notion of Heimat was interrogated, as organizers and conference speakers committed themselves to the title’s call for a critical de-heimatization of “it”—the pronoun “it” being a placeholder for national identity and belonging, national(ist) politics and history, assimilationist integration policies, and, generally, anything that the speakers and audience may have wished to project onto “it”. In the context of our discussion of art in public spaces, the fourth salon set a new and more radical standard for how artists and institutions can use strategies of agitation, as well as mobilizing conflictual aesthetics in order to make interventions in public spaces to contest hegemonic structures and nationalist sentiments, thereby impacting public discourse and public opinion.

Above, we have defined postmigrant public spaces as plural and sometimes conflictual arenas of human encounter shaped by immigration, nationalism and social inequity. What more can we learn about postmigrant public spaces from the example of the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon? What are its postmigrant characteristics? To begin with, it should be emphasized that the bringing together of people from different institutions, artforms, disciplines and (activist) organisations enabled the salon to span multiple platforms, as well as mediating the frictions that inevitably exist between differently positioned individuals and milieus. In doing so, the event interconnected people with different political positionalities, various types of professional expertise and different life experience and heritage in a coalitional way that provided a fertile ground for the forging of postmigrant alliances. According to Foroutan’s definition, postmigrant alliances are based on strategic bridge-building between migrant and non-migrant actors who pursue a common goal. By bringing together different people based on a type of experience that is shared but not necessarily identical—such as migration, racism or discrimination—or based on a common political stance, postmigrant alliances enable new interest-based relationships to develop “beyond homogenous peer groups”.Footnote13 Furthermore, the durational character of the Gorki Theatre’s commitment to organizing thematic postmigrant biennials since 2013 is also significant as it has enabled the institution to build a network of like-minded, politically engaged collaborators and artists.

It is important to stress that, historically, the production of public spaces and publics has always been at the core of the role that art institutions have fulfilled in modern society (von Osten Citation2011, 60–62). We submit that a crucial component of the Gorki Theatre’s success in curating public spaces is the choice of a biennial format, with a thematic focus closely linked to the ongoing postmigrant political struggles. Or, to use Marchart’s term, the Gorki Theatre sought to turn their biennials into “potentially powerful counterhegemonic machines” by openly acknowledging their partisan nature (Citation2019, 26).

As a locally embedded and transculturally connected set of platforms for the arts and for public debates, the Herbstsalon format possesses a clear potential for generating relatively open forums that afford the publics that emerge within them a space to discuss issues related to the themes and agendas of the salons. In the 4. Berliner Herbstsalon, it was feminist and postmigrant de-heimatization, understood as a decolonizing struggle for recognition, equality and the acknowledgement of multiple belonging. To stir debate, the salon joined together art, theory and politics. It harnessed artistic and curatorial practices to articulate the theme and politics of de-heimatization in an aesthetically and intellectually challenging way. Moreover, scholars were welcomed on board to theoretically develop the notion of de-heimatization into an instrument of social critique, and to discuss the topic among themselves and with the audience at the conference.

In regard to the exhibition and the other events, the organizers employed insistent forms of addresses to ask visitors to reflect critically upon the national(ist) discourses and the essentialist constructions of Heimat. In doing so, they also sought to inspire visitors to think otherwise and creatively reimagine homeplace and belonging by drawing together, from their own subjective perspective, the salon’s different but nonetheless interconnected strands of postmigrant, feminist and anti-capitalist thinking and art-making. Furthermore, the Gorki Theatre’s collaboration with activist groups in connection with the biennial’s conference might, in part, explain its consistent use of agitational modes of address and the emphasis on an accountable and politically positioned public.Footnote14 Lastly, but no less importantly, the multi-sited spatial structure of the salon—so typical of art biennials, where some events and exhibits are deliberately transferred to smaller venues frequented by other types of users—underscored that the salon addressed a plurality of publics.Footnote15 The publics attracted to the salon by the outspoken anti-nationalism of its agitational title could perhaps be described as counterpublics, in the sense that they were likely to be structured by other than nationalist dispositions and to make different and potentially transformative assumptions about what belonging, homeplace, equality, nation, identity and learning from historical violence could mean and involve in contemporary postmigrant Germany. Therefore, the example of 4. Berliner Herbstsalon encapsulates how the changing roles of art in public spaces have significantly strengthened art’s political, activist and coalitional potential and its ability to imagine societies otherwise, all of which testifies to the significance of art in public spaces and political arenas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Ring Petersen

Anne Ring Petersen is Professor at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Her research explores transcultural and migratory approaches to art and cultural production, focusing especially on the transformative impact of migration, postmigration and globalization on contemporary art practices and identity formation. Recent publications include Migration into art: Transcultural identities and art-making in a globalised world (2017) and the co-authored book Reframing Migration, Diversity and the Arts: The Postmigrant Condition (2019).

Sabine Dahl Nielsen

Sabine Dahl Nielsen is postdoc at the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen. Her research examines how curatorial practices can create social contact zones and stage conflict-sensitive situations that contribute to the negotiations of today’s migration-related problematics. Recent publications include “Multi-sited curating as a critical mode of knowledge production,” in Curatorial Challenges (2019) and “Flow and Friction in the Crisis of Globalisation: Negotiating Mobility and Migration Politics at Public Transit Sites,” in Transit: Art, Mobility and Migration in the Age of Globalisation (2019).

Notes

1. For a discussion of the significant historical and aesthetic overlaps and interconnections between theatre and installation art, see Chapter 7 “Installation between image and stage” in Petersen, Anne Ring Citation2015, 239–287.

2. For a comprehensive English-language account of the concept of postmigration and the academic debates, see: Schramm, M., S. P. Moslund, and A. R. Petersen, eds Citation2019. For the recent German debates, see: Foroutan Citation2019; Foroutan, Karakayali, and Spielhaus Citation2018; Hill and Yildiz Citation2018.

3. The ambition to do a mapping of art in public spaces as a field is perhaps most evident in two catalogue entries which attempt a survey: Grasskamp Citation1997; Franzen, König, and Plath Citation2007. The 2007 catalogue also includes an annotated bibliography, listing publications on art in public space from the period 1970–2007.

4. For a sound overview of the theoretical and empirical accounts on public art to complement the references in this article, we refer to the following studies performed within the field of art history, or, alternatively, in the interzone between the humanities and the social sciences: Kester Citation2004; Miles Citation1997; Mitchell Citation1992; Thompson and Sholette Citation2004; Nielsen Citation2015; Zebracki Citation2012.

5. For more elaborate discussions of these terms, see: Petersen Citation2021; Nielsen and Petersen Citation2021.

6. In addition to the studies discussed below, influential theorizations and critical discussions include: Möntmann Citation2017; Meskimmon Citation2020; Sheikh Citation2005, Citation2006.

7. For an astute and nuanced discussion of what socially engaged art may and may not accomplish with respect to social change, see: Kester Citation2017.

8. For an introduction to the debates on the participatory turn in cultural policy studies, see: Sørensen, Korbek, and Thobo-Carlsen Citation2016.

9. For an insightful overview and thorough discussion of the developments based on Norwegian and Danish examples from the 2010s, see: Danbolt Citation2020.

10. According to Mouffe, it is necessary to view public spaces as pluralistic and conflict-ridden spaces where divergent subject positions are not seen as enemies but as adversaries whose legitimate existence should be acknowledged, but whose views can rightly be disputed. By introducing the concept of adversaries—understood as responsive opponents—Mouffe seeks to clarify the concept of antagonism. On the one hand, she uses the concept of antagonism in the original sense of the word, referring to the conflict between two irreconcilable enemies who share no symbolic space. On the other hand, she introduces the term agonism, by which she refers to the conflict between responsive adversaries who are positive towards each other because they share a symbolic space, but who still fight against each other because they want to understand, interpret and administer this space in different ways. On the basis of this distinction between antagonism and agonism, Mouffe concludes that having an agonistic public space has to take the form of a constant struggle to transform antagonism to agonism (Mouffe Citation2009, 102–103).

11. Marchart claims that, although it is today widely recognized that art is political, the ideology of the art field is still structured around the old Adornian understanding that the political nature of art is paradoxical and subtle: “it is political, we are told, precisely in being not political […] The less art is explicitly political, we are let to conclude from this, the more political it actually is” (Marchart Citation2019, 13–14). According to Marchart, Rancière’s theory has been put in the service of this depoliticizing ideology. Hence, Rancière’s proposition that art’s potential for “redistribution of the sensible” enables it to reframe material and symbolic spaces has been widely adopted by art world professionals as philosophical legitimation that whatever is produced by “antipolitical artists and curators” is truly political (13–14). For Marchart, the problem is twofold: not only does this ideology dilute the very idea of political art but it also serves to exclude explicitly political art from the art field. Marchart’s trenchant critique of Rancière’s followers is certainly directly pertinent to the art market as well as many traditional art museums, but we find the way in which his broad generalization tends to strip art that is not explicitly political of political agency and efficacy questionable. Moreover, although we find his distinction between three modes of political engagement in art (which he derives from Mouffe) analytically helpful, we do not subscribe to Marchart’s evaluative hierarchization of these modes. It should also be mentioned that Marchart’s critique of the ideology of the art field sometimes evades the fact that, in the twenty-first century, overtly politicized art has increasingly been embraced and promoted by small-scale art institutions and biennials, which constitute some of the most vital sources of the renewal of art from within the art field itself. At other times, he acknowledges the critical and political potential of institutions to operate as “counter-hegemonic machines” (26), as we explain below.

12. According to Mouffe, political confrontation is not necessarily instigated by an outsider, i.e. by someone not belonging to a given community. Rather, she argues that conflictual participation is instigated by persons who disagree, who have other points of view and who are not part of the prevailing consensus within the community. We will argue that by emphasizing the fact that conflictual participation and radical political change is often initiated by “outsiders to the consensus” (Miessen and Mouffe Citation2010, 118) rather than by outsiders to the community, Mouffe effectively counteracts a latent tendency within the framework of Miessen’s The Nightmare of Participation to celebrate an individualized, exteriorized and culturally marginalized outsider positionality.

13. Andreas Wimmer, quoted in Foroutan Citation2019, 199.

14. For example, the fourth panel of the conference “Deheimatize Belonging” was entitled “What Does It Mean in Action?”. This took place on the stage of the Maxim Gorki Theatre, where activist approaches were explored by Olubukola Gbadegesin, Ethel Brooks, Donna Miranda and Esra Karakaya in direct dialogue with those attending the panel.

15. The first day of the conference “Deheimatize Belonging” was held in the Senatssaal of the Humboldt Universität, the second day at the Gorki Theatre. The conference was followed by a string of closed sessions and discussions with speakers such as Shermin Langhoff, Grada Kilomba, Marta Górnicka, the artist and activist group Centre for Political Beauty, and curators from Savyy Contemporary, all held at the theatre. In addition to the works installed in public space, the exhibition comprised works installed in several venues: Palais am Festungsgraben, Zeughauskino im Deutschen Historischen Museum, East Side Gallery, Haus der Statistik and Scotty.

References

- Bala, S. 2018. The Gestures of Participatory Art. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Begrich, Al., A. Diestelkamp, Ç. Ilk, A. Lange, L. T. Musiol, and El. Sinanina 2019. 4. Berliner Herbstsalon. Kunst. Berlin: Maxim Gorki Theatre. guidebook.

- Bishop, C. 2004. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October 110 (Autumn): 59–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/0162287042379810.

- Bishop, C. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

- Bolt, M., C. U. Schmidt, S. M. Strandvad, A. M. Lindelof, and K. Samson. 2014. “Forord.” Kultur & Klasse 42 (118): 5–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.7146/kok.v42i118.19832.

- Bourriaud, N. 1998. Ésthétique relationelle. Paris: Les presses du réel.

- Cartiere, C. 2013. “Book Reviews: Kester, Grant H. The One and the Many.” Public Art Dialogue 3 (1): 132–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21502552.2013.766875.

- Danbolt, M. 2020. “Into the Friction.” Kunstkritikk: Nordic Art Review: n.p. https://kunstkritikk.com/into-the-friction/ Accessed 19 August 2020

- Falk, J., and L. Dierking, eds. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Foroutan, N. 2019. Die postmigrantische Gesellschaft: Ein Versprechen der pluralen Demokratie. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Foroutan, N., C. Canan, B. Schwarze, S. Beigang, and D. Kalkum. 2015. Deutschland postmigrantisch II. Einstellungen von Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen zu Gesellschaft, Religion und Identität. Zweite aktualisierte Auflage. Berlin: Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

- Foroutan, N., J. Karakayali, and R. Spielhaus, eds. 2018. Postmigrantische Perspektiven: Ordnungssysteme, Repräsen-tationen, Kritik. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

- Franzen, B., K. König, and C. Plath. 2007. “Preface: Using the Example of Münster.” In Sculpture Projects Muenster 07, edited by B. Franzen, K. König, and C. Plath, 11–17. Cologne: Buchhandlung Walter König.

- Grasskamp, W. 1997. “Art and the City.” In Sculpture. Projects in Münster 1997, edited by K. Bußmann, K. König, and F. Matzner, 7–41. Ostfildern-Ruit: Gerd Hatje.

- Haas, H. de, S. Castles, and M. J. Miller. 2020. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Sixth Edition. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hein, G. 1998. Learning in the Museum. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hill, M., and E. Yildiz, eds. 2018. Postmigrantische Visionen: Erfahrungen - Ideen - Refleksionen. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Jacob, M. J. 1995. “Outside the Loop.” In Culture in Action, edited by Michael Brenson et.al., 50-61. Seattle: Bay Press.

- Kester, G. H. 2004. Conversation Pieces: Community + Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kester, G. H. 2011. The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kester, G. H. 2017. “The Limitations of the Exculpatory Critique: A Response to Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, No 53: 73–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v25i53.26407.

- Krauss, R. 1987. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” In The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, 276–290. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Kwon, M. 2002. One Place after Another. Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Laclau, E., and C. Mouffe. 2001. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. 1985. London: Verso.

- Lacy, S. 1995. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle: Bay Press.

- Langhoff, S. 2020. “Taking History Personally: Knowing that neither Memories are Already Memory, nor Stories Already History.” European Journal of Theatre and Performance 2: 484–487.

- Marchart, O. 2007. “The Curatorial Function: Organizing the Ex/position.” In Curating Critique, edited by M. Eigenheer, B. Drabble, and D. Richter, 43–46. Frankfurt am Main: Revolver.

- Marchart, O. 2019. Conflictual Aesthetics: Artistic Activism and the Public Sphere. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Meskimmon, M. 2020. Transnational Feminisms, Transversal Politics and Art: Entanglements and Intersections. London: Routledge.

- Miessen, M. 2010. The Nightmare of Participation (The Crossbench Practice as a Mode of Criticality). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Miessen, M., and C. Mouffe. 2010. “Democracy Revisited (In Conversation with Chantal Mouffe).” In The Nightmare of Participation 105–159. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Miles, M. 1997. Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures. London: Routledge.

- Mitchell, W. J. T., ed. 1992. Art and the Public Sphere. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 105–159

- Möntmann, N. 2017. Kunst als sozialer Raum: Andrea Fraser, Martha Rosler, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Renée Green. Cologne: Walter König.

- Mouffe, C. 2005. “Which Public Space for Critical Artistic Practices?” In Cork Caucus: On Art, Possibility & Democracy, edited by T. Joyce, 149–171. Berlin: Revolver Publishing.

- Mouffe, C. 2007a. “Art and Democracy: Art as an Agonistic Intervention in Public Space.” Open! Platform for Art, Culture and The Public Domain, no. 14: 1–7. https://www.onlineopen.org/art-and-democracy

- Mouffe, C. 2007b. “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces.” Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1 (2): 1–5.

- Mouffe, C. 2009. The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso.

- Nielsen, S. D. 2015. “Kunst i storbyens offentlig rum. Konflikt og forhandling som kritiske politiske praksisser.” PhD thesis, Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, University of Copenhagen.

- Nielsen, S. D., and A. R. Petersen. 2021. “Enwezor’s Model and Copenhagen’s Center for Art on Migration Politics.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 48 (May): 70–95.

- O’Neill, P., and M. Wilson. 2010. “Introduction.” In Curating and the Educational Turn, edited by P. O’Neill and M. Wilson, 11–22. London: Open Editions/de Appel.

- Osten, M. von 2011. “Producing Publics - Making Worlds! On the Relationship between the Art Public and the Counterpublic.” On Curating. Special Issue on “Curating Critique” 9: 59–57.

- Petersen, A. R. 2021. “The Square, the Monument and the Reconfigurative Power of Art in Postmigrant Public Spaces.” In Postmigration: Art, Culture and Politics in Contemporary Europe, edited by A. M. Gaonkar, A. Ø. Hansen, H. C. Post, and M. Schramm, 233-262. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Petersen, Anne Ring. 2015. Installation Art: Between Image and Stage. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Rancière, J. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum.

- Rancière, J. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator. London: Verso.

- Rancière, J. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. London: Continuum.

- Raunig, G. 2013. “Flatness Rules: Instituent Practices and Institutions of the Common in a Flat World.” In Institutional Attitudes. Instituting a Flat World, edited by P. Gielen. Amsterdam: Valiz. 167–178

- Reestorff, C. M. 2017. Culture War: Affective Cultural Politics, Tepid Nationalism and Art Activism. Bristol, Chicago: Intellect.

- Schramm, M., S. P. Moslund, and A. R. Petersen, eds. 2019. Reframing Migration, Diversity and the Arts: The Postmigrant Condition. New York: Routledge.

- Sheikh, S. 2005. In the Place of the Public Sphere?, Critical Readers in Visual Cultures. Berlin: b_books.

- Sheikh, S. 2006. “The Trouble with Institutions, Or, Art and Its Publics.” In Art and Its Institutions, edited by N. Möntmann, 142–149. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Simon, N. 2010. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

- Sørensen, A. S., H. B. Korbek, and M. Thobo-Carlsen. 2016. ““Participation”, Introduction to themed issue on Participation.” The Nordic Journal of Cultural Policy 19 (1): 4–16.

- Splichal, S. 2010. “Eclipse of “the Public”: From the Public to (Transnational) Public Sphere. Conceptual Shifts in the Twentieth Century.” In The Digital Public Sphere: Challenges for Media Policy, edited by J. Gripsrud and H. Moe, 23–38. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Sternfeld, N. 2013. “The Rules of the Game: Participation in the Post-Representative Museum.” In CuMMA PAPERS. https://cummastudies.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/cummapapers1_sternfeld.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2021.

- Thompson, N., and G. Sholette. 2004. The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT and Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

- Warner, M. 2005. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

- Zebracki, M. 2012. Public Artopia: Art in Public Space in Question. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.