ABSTRACT

This article presents a comparative analysis of works of Caribbean art and literature that engage in a mutual project of addressing the paradox of the colonial archive. Trinidadian-Canadian writer M. NourbeSe Philip crafted her long poem Zong! from an eighteenth-century legal document about the murder of 132 enslaved Africans onboard the slave ship of the same name. Exposing the dehumanizing language of historical record from which she nonetheless extracts affective and poetic scraps of human experience, Philip shows the power and necessity of artistic intervention in the colonial archive. The similarities between Philip’s literary strategies and Belle’s artistic interventions in the archive of the Danish (now U.S.) Virgin Islands are striking, and the two illuminate one another. Focusing on Belle’s series entitled Chaney (We Live in the Fragments), the analysis delves into her work with “chaney,” a Creole term for the colonial-era shards of china that wash out of the soil of the Virgin Islands as a reminder of the centuries-long Danish presence there. Belle’s art is both counter-archival and counter-canonical in her direct address to the national Danish institution of the Kongelige Porcelainsfabrik, or Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Factory. Both the poem and the artwork focus on the aesthetic of the fragment, whether in terms of the fragmented nature of the colonial archive with its many blind spots, the fragments of lost narrative that Philip scatters across the page, or the fragments of pottery that Belle transforms into paintings and ceramics that evoke the disjointed nature of Caribbean identity. Framing Zong! and Chaney with the notion of “comparative relativism,” the article draws on literary and art historical methodologies to reveal an important transdisciplinary approach to Caribbean archives and to the creation of cultural memory.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

The colonial archive poses a paradox to artists and scholars engaged in trying to understand history’s intimate realities. Framed by dehumanizing discourses and perspectives, these archival materials occlude more than they include with the result that they can best be approached as fragments, remains, and ruins of historical record—and yet, as such, they do provide evidence with which to work. For this reason, many Caribbean writers including M. NourbeSe Philip, Dionne Brand, Maryse Condé, Michelle Cliff, Patrick Chamoiseau, Fred D’Aguiar, Tiphanie Yanique, and others, have explored ways of using the archive while at the same time challenging its authority and pointing to its failures. By some definitions, archives take the form of static caches of documents and materials located in formal institutions but even those items are iterative as they play out in critical and creative engagements with them. In Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism Ariella Azoulay challenges the authority of such collections with an excellent question she poses with regard to recent “alternative” engagements with archives. She cautions that even alternative approaches tend to reify the notion of a sovereign and neutral archive in the first place, asking “why are different modalities of engagement with the archive kept apart from the archive as if its essence is immune to them?” (Azoulay Citation2019, 197). Indeed, counter-archival works approach the archive as a colonial product and as an ongoing critical process that, crucially, folds in interpretive acts both scholarly and creative. In the Caribbean, local histories are swathed in multiple layers and waves of colonial rule and representation. As a result, Caribbean writers and artists whose work contributes to cultural memory seek the past through creative and affective modes in the face of the profoundly compromised nature of archival record. In telling the stories of people and events resistant to colonial power, these works draw from tatters and scraps of archival material that, while mere remains of the stories they tell, provide points of reference for the kind of cultural memory sustained in these artistic interventions.

Azoulay focuses on archives created and preserved by the state, which she regards as sites of historical disaster and tools of state violence; she concludes, “the imperial archive … is a graveyard of political life” (Azoulay Citation2019, 186). It is, I would add, a graveyard of cultural memory that nonetheless haunts. The editors of Decolonizing the Caribbean: An Archives Reader address the relationship of records to memory in their presentation of the contradictions of the colonial archive: “archives and records, as representatives, containers, and promulgators of official actions, have always been central to the colonial enterprise” while at the same time they “refer to the community itself as both a record creating entity and as a memory frame that contextualizes the records it creates” (Bastian, Aarons, and Griffin Citation2018, 2–3). They cite a “fluidity” to the archive and a “synergy between actions and records” (3)—which is to pair cultural memory with archives in a shifting and often uneasy mutual meaning-making project. Rather than imbuing the leftover records of empire with the kind of power and primacy that historians have long accorded them, the archivists and critics in this “archives reader” show the blind spots of colonial archives while demonstrating the ways in which even these partial and contested materials, this ruin of a record, is a useful touchstone for decolonial forms of memory—particularly in artistic and creative rejoinders to it.

One artist who emphasizes the theme of counter-archival engagement throughout her extensive body of work is Virgin Islands artist La Vaughn Belle. Belle works in an impressive array of genres and media, from painting and photography to written text and large-scale statuary in the case of the stunning monument she made in collaboration with Danish artist Jeannette Ehlers, I Am Queen Mary. This sculpture of one of the St. Croix women who led an 1878 labor revolt known as the Fireburn was unveiled in Copenhagen in 2018 as a singular reminder of Denmark’s 250-year colonial presence in the Virgin Islands. As a prominent public marker of Denmark’s colonial history, it also epitomizes the power of art to create cultural memory in the face of historical erasure. That is, before Queen Mary took center stage in the harbor of its capital city, Denmark’s imperial past was relegated to the margins of its national narrative and even then as an auxiliary, exotic site of the imagination. In her book about the Danish West Indies, Ingen udskyldning [No Excuse], Astrid Nonbo Andersen notes that “I omtalen om kolonitiden … har rammefortællingerne længe været præget af idéen om det, jeg har valgt at kalde den uskyldnige kolonialisme” [In the narrative of colonial times … the frame narrative has long been glossed over with the idea of what I have chosen to call blameless colonialism] (Andersen Citation2017, np) based on a rose-colored view of Danish benignity. Similarly, Karen Fog Olwig characterizes “Danish memory” of the country’s colonial history as “liv[ing] on in patriotic narratives of the former Danish empire that helped boost a national image of former grandeur” (Olwig Citation2003, 209).Footnote1 The monument counters such nostalgic or benign narratives as well as the formal evidence that does exist regarding the event of the Fireburn: in the archival materials surrounding the event, Mary and her fellow “queens” who led the revolt appear only as prisoners and defendants in trials where their guilt was a foregone conclusion.Footnote2 The archival record forecloses their courage, their motivations, and the strength and beauty that the monument imprints in public space. Indeed, Belle describes her body of work as “counter-archival,” and I Am Queen Mary demonstrates just how counter-archival art and literature work from and simultaneously against archival record.Footnote3 I was struck, as a literary scholar, by the resonance between many of Belle’s works and those by Caribbean writers who are at once compelled and repelled by the colonial archive. These works address archives not as primary source materials but as remnants that they explore as just that. By intertwining literary examples, most prominently M. NourbeSe Philip’s long poem, Zong!, with Belle’s series Chaney (We Live in the Fragments), I identify strategies of counter-archival representation that cross genre and discipline.

The method of comparison I follow is one that art historian Anne Ring Petersen and literary scholar Karen-Margrethe Simonsen team up to present in one of the first scholarly assessments of I Am Queen Mary, which they read together with the eighteenth-century autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. In their own criss-crossing of history and genre they stage an argument for “relational comparatism.” Noting that Equiano is more often read among other writers like Frederick Douglass and that a more intuitive comparative piece for I Am Queen Mary might be the iconic photograph of Huey P. Newton to which it clearly alludes, they propose that interdisciplinary comparatism is both fruitful and, in the context of globalization and in particular of the hemispheric history of trans-Atlantic slavery, necessary. They point out that works dealing with the history and legacies of slavery have in common an endemic hybridity in their address to overlapping national, regional, and imperial frameworks of power—a case that Belle and Ehlers make in the subtitle on the plaque on their sculpture: “A Hybrid of Bodies, Nations and Narratives.” Petersen and Simonsen observe that the monument occupies inherently comparative contexts as “en dialog mellem to kunstere og dermed repræsenterer en genforhandling af den danske nationale selvforståelse og historie, hvor danske og carabiske perspektiver gensidigt udfordrer hindanden” [a dialogue between two artists and with that a renegotiated representation of Danish national identity and history in which Danish and Caribbean perspectives mutually challenge one another] (Petersen and Simonsen Citation2019, 44).Footnote4 Beyond the process of the its production, I Am Queen Mary is a comparative figure in that it “er på gang eftertrykkeligt national (det kritiserer dansk kolonialisme) og transnationalt (det bygger på dansk-vestindiske forbindelser), og det forener vestlige og afrikanske-disaporiske billedtraditioner til en ganske særlig stedspecifik og udpræget politisk blandning af det lokale og det globale” [is at once emphatically national (it criticizes Danish colonialism) and transnational (it builds upon Danish-West Indian ties), and it combines Western and African Diasporic artistic traditions in a quite unique, site specific, and pronounced political blending of the local and the global] (46). Theirs is a compelling argument for the transformative potential of relational comparatism upon which I draw in this reading of Philip’s poem and Belle’s painting in their mutual address to adjacent histories in the Caribbean and the overlapping global networks embedded in those histories. Petersen and Simonsen lay out multiple guiding principles of relational comparatism (context, dynamics/agency, circulation), and my reading of Zong! and Chaney centers specifically on the dynamics and agency of their mutually counter-archival interventions and creations.

Counter-archival poetry

As one of the clearest examples of this methodology, I offer a brief reading of Philip’s Zong! In diving into the wreck of the colonial archive, Philip lays bare the violence of both absent information and recorded language. Laurie Lambert emphasizes the paired dynamics of “recognition and repair” in her reading of Zong! when she says, “In the face of historical sources that do not recognize the humanity of Africans, Philip makes poetry a literary ‘source’ to be worked through in conversation with historical sources” (Lambert Citation2016, 107). Lambert shows how Philip extracts recognition from the wreckage of the archive in an act that I have elsewhere termed “wreckognition”: “out of a sea of statistics, accounting ledgers, and legal decisions, Philip extracts a discourse of recognition and repair through the invention of names, kinship ties, languages, and ethnicities for the dead” (Lambert Citation2016, 110).Footnote5 Philip extends and absorbs the archive into her poem, which is now every bit as much a source of information about the 1781 event it addresses as the historical document from which the poet works—in an example of the open-ended and continuously iterative nature of the archive. Philip’s long poem draws directly from the archive by repurposing a specific 18th-century document, the court decision in the Gregson vs. Gilbert case. This notorious legal contest addressed an insurance claim made by the owners of a slave ship whose crew had thrown at least 132 enslaved people overboard and then petitioned for insurance payment for so-called “lost goods.” As a perverse but seminal text in the history of abolition, the decision records the court’s condemnation of the crew’s actions and refusal to grant compensation. Yet its language is begrudging at best and violent at worst. Philip pointedly prints the decision in its entirety on the last pages of her book to lay bare its discourse of inhumanity. Even though the document concludes that the crew’s acts were unjustified, its language perpetuates the very violence it condemns. The exculpatory statement reads, “a sufficient necessity did not exist for throwing the negroes overboard, and also … the loss was not within the terms of the policy.” This is the record of a morally correct decision rendered in utterly immoral terms. How in the world is one to read this story given the ruination in which its documentation lies? Like the debris of a destroyed building, the text is a piece of a larger story, but that story was compromised at the moment of its inscription.

Philip begins her address with the statement that “there is no telling this story,” and she makes the connection between art and literature herself in her Notanda at the end of her book in which she explains, “I use the text of the legal report almost as a painter uses paint or a sculptor stone … to remove all extraneous material to allow the figure that was ‘locked’ in the stone to reveal itself” (Philip Citation2008, 198). Philip builds her poems out of the material of the archive while simultaneously demonstrating its ruination. In the first of six sections, she scripts a series of poems in which she scatters letters, syllables, and words across the page so that each word floats on white paper, often in pieces, apart from the others. The first page of “Zong #24” reads

Figure 1. Zong! (Philip Citation2008, 41)

Representing the ruination of the document in the poem’s fragmented form, replete with gaps and empty space, Philip punctuates it with the present tense: “is.” Even as the poem alludes to the story of the event, the evidence, and the factors at hand in the case, it refuses any but two verbs: “is” and “murder,” a word that is simultaneously a verb and a noun. And yet in the source material, the word “murder” only occurs in this sentence: “The argument drawn from the law respecting indictments for murder does not apply.” Philip rips this word from the original text in which the crime is not upheld and makes it the subject and the indictment of her poem.

In other poems, Philip isolates a particular part of speech, such as verbs that change tense but never find a subject, and in her opening poem she presents floating, drowning letters and syllables that never find a word (“Zong #1”). Philip’s text is an excellent segue to Belle’s counter-archival art since Zong! is itself a visual and sonic text .Footnote6

Figure 2. Zong! (Philip Citation2008, 86)

As this sample of its undulating verse illustrates, the shape of the text is integral to its linguistic expression. Here, the words are drawn toward one another by the semantics of iron—iron manifest in imprisoning irons, iron is it forms and is formed by tongs, as it rings out in the form of a bell. The verse is in equal parts cinched together by sound, in this case the sound of the letter “g” which, visually, hangs on the majority of the words scattered across the page. The visual dimensions of the “g”s combine with the sonic tones of the sound it makes deep in the mouth, along with the “ding,” “dong,” “sing,” and seemingly sung italicized words iya and mama. Later in the poem, Philip again draws on the visual to emphasize the ghostly presence of the victims of the Zong by switching to faded, overlapping, often illegible print on the page.Footnote7 Philip’s strategic use of fragments as a principle of telling a story that, in turn, fragments archival documentation into a form accessible to the reader’s cultural memory offers an example of counter-archival art that is uncannily similar to Belle’s visual art in her Chaney series.

Archives of the Danish Virgin Islands

Whereas Philip works with a single document and event, Belle addresses a sprawling colonial archive with a very particular narrative of its own. The situation of the Danish West Indian archive with which Belle works illustrates the ruinous nature of colonial archives on multiple levels. During Denmark’s two and a half centuries of colonial rule over the Virgin Islands (including St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John), Danish government functionaries kept some of the most meticulous and thorough records in the Caribbean but they did so in such a way that their method and their treatment of these records illustrate how such archives can and do work against the representation of the very people to whom they refer. Gunvor Simonsen explains in her in-depth look at court records of the Danish Virgin Islands how the nearly 200 volumes of court depositions in the archive contain the voices of enslaved people but in such a way as to distort them through a framework that sustained only criminality. Simonsen notes, “slaves spoke, but to little avail” (Simonsen Citation2017, 14), and in the robust Danish court system, “representation was a daily routine, but … it went hand in hand with distortion and the exclusion of particular experiences” (Simonsen Citation2017, 16). To start, these court transcriptions mask rather than enshrine the speech utterances on which they are predicated due to the fact that Danish was the official language of government records even though the vast majority of the population of the Virgin Islands did not speak it, but rather conversed in Dutch Creole, English Creole, and English. Court proceedings would be translated into Danish at the moment of their transcription, a practice that categorically interpreted and muted the voices of those trying to defend themselves. Someone speaking Creole or English would be cut off from access to their own words through this process. Simonsen shows how statements made by enslaved people, while recorded for posterity, were shaped by the procedures and transcriptions themselves. The examples she provides also demonstrate a shift in voice from first person utterance into a third person voice that foregrounds the language and presence of the legal clerk over the speaking subject. She notes the various manipulations involved in “turning the vaporous words uttered by enslaved people into stable signs on paper, carrying legal validity” (Simonsen Citation2017, 46). Then, on top of these linguistic acts of memory theft, the records of the Danish West Indies were packed up and removed to Copenhagen upon the sale and transfer of the Virgin Islands to the U.S. in 1917, which meant that Virgin Islanders had no local or even metropolitan access to their own history, as distorted and partial as its remaining evidence was. As the members of the Virgin Islands Studies Collective, La Vaughn Belle, Tami Navarro, Hadiya Sewer, and Tiphanie Yanique sum up the archival scenario and its consequences, “As many of the records of the 250 plus years of the Danish colonial period were produced in Danish instead of the English that was most commonly spoken, this has contributed to a compounded lack of access both in language and in distance. The result for Virgin Islanders is a community that has struggled owning its historical memory” (Belle, Navarro, Sewer, and Yanique Citation2019,20).

On this point, Jeannette Bastian’s book about the Virgin Islands, Owning Memory: How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History, argues that as partial and even violent as colonial records could be, they nonetheless provide an important touchstone for collective identity. She explores the relationship between “communities of records” and social community, demonstrating the interplay between the two. If the documents are not even available as sources of information or targets of refutation, it becomes all the more difficult to embrace cultural memory.Footnote8 As is the case in her co-authored introduction to the archives reader, Decolonizing the Caribbean, Bastian is cautious about the relationship between archives and memory given the role that archives play in reifying colonial order—but there is a relationship nonetheless. Even as the Danish archives silence non-Danish voices and languages and effectively forget the lives of the colonized, she argues that “archives can be both physical spaces and memory spaces … containers of the collective memory of their creators as well as their users and interpreters” (Bastian, Aarons, Griffin Citation2003, 13). Counter-archival readings and interpretations are yet in dialogue with the archive.

Much of the vast Danish West Indian archive was digitized and made available to the public by the Danish National Archives in 2017, the centennial year of the end of Danish rule. In tandem with this project, the Royal Danish Library hosted a special exhibit in which Belle’s work was featured, Blinde vinkler/Blind Spots. The title of the exhibition indicates the dynamic of the archive in that while the point was to mark the new availability of heretofore unavailable troves of documentation about the Danish colonial period, the emphasis of the curators was on the “blind spots” that lace this material. This is an important semantic move in that colonial archives are profoundly incomplete and they unravel even as we try to read them because their point of view is so constricted and occlusive. They provide a record of experiences and, in the records related to slavery and the plantation system, human rights abuses through an almost entirely Danish point of view even though they pertain to the history of the Virgin Islands. It’s a wreck of a record for anyone interested in understanding what life was like for the majority Black Virgin Islanders. The records, rather than providing information, withhold it.Footnote9 This is precisely the dynamic that drives counter-archival art and literature whether in a Danish, English, French, Spanish, Dutch, etc., colonial context. We can read against its grain with all of our critical faculties, but critical intervention cannot go where creative rejoinder can.

Counter-archival art

Belle’s Chaney (We Live in the Fragments) series materializes the traces of the Danish colonial era and brings to light forgotten histories. The word “chaney” is a Creolism that combines the words “china” and “money” and refers to shards of colonial-era porcelain that wash out of the landscape from time to time, as after a hard rain. As Belle explains in her artist’s statement: “Originally from pieces of colonial fine china imported both in display of and as a result of the wealth of the plantation economy, ‘chaney’ serves as a reminder of both the colonial past and the fragmented present of Caribbean societies. These shards tell the visual stories of power and projection and how cultures reimagine themselves in this vast transatlantic narrative” (Lavaughbelle.com). And, in another discussion she describes how children transform these colonial artifacts into toys: “Children used to round them [pieces of chaney] to look like coins and used them as play money” (Belle and Wilson). Similarly, it is used in Virgin Islands jewelry, which speaks to the cultural ubiquity of chaney in the Virgin Islands—and indeed the archive from which chaney springs is more of a cultural archive than one composed of documents.Footnote10 The china itself is an artifact of Danish colonialism but by using it in art, jewelry, and even children’s games Virgin Islanders shift its value into a fully Caribbean cultural context.

Belle takes multiple approaches to these broken pieces of pottery: in one series, she paints them onto large rectangular panels, thus amplifying otherwise overlooked artistic flourishes and details in the pattern while separating them out from the pattern itself. This is a metaphorical resistance to the logic of the colonial archive in that the colonial archive is shaped to represent order and to legitimize imperial endeavor as a complete narrative while it is in fact composed of scraps and fragments. Chaney organically breaks down wholeness, symmetry, and complete patterns, and Belle’s art captures the disruptive aesthetic and inner beauty of the fragment itself. By zooming in on a broken piece of china and its intricacy, the series disavows the notion of pattern that would have centered or structured the original object. Indeed, in a conversation about Dionne Brand’s counter-archival long poem, The Blue Clerk, Saidiya Hartman notes Brand’s challenge to “the economy of the colonial archive” to which Brand adds that “all coloniality is order” (Brand and Hartman Citation2018). While the materials of the archive are partial and problematic, institutional archives are nevertheless predicated on a notion of temporal order, or linearity, that is integral to what Lee Edelman identifies as “liberal histories [that] build triumphant political narrative with progressive stories of improvement and success” (in Caswell Citation2021). Michelle Caswell explicates the coercive nature of linear temporalities in Urgent Archives, in which she “uncovers the whiteness and heteronormativity of dominant archival temporalities that fix the record in a singular moment in time and imbue it with the potentiality of future use” (Caswell Citation2021, 26). The randomness and endlessly iterative structure of Brand’s poem challenges the notion of authoritative order as well as that of wholeness.Footnote11 This same principle is at work in Chaney, in which the fragment disrupts the logic of the European design, literally broken on colonial shores.

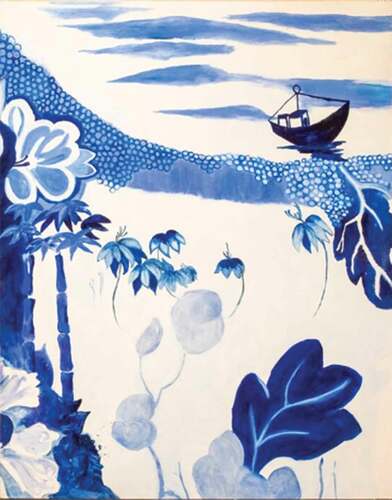

To look more closely at some of the individual pieces, the large-scale paintings present the viewer with a mixture of abstract designs and impressions of plants and landscapes. Most of the fragments feature shapes that might be absorbed into a larger pattern but stand out in their own specificity in Chaney (). includes a silhouette of a ship—yet even in that image, the ship appears as a fragment of itself, cut off by the painting’s edge, and the seascape that coheres with clouds in the sky above it disintegrates into floating floral details beneath the seeming surface of the sea. This image, like others in the series, disrupts the traditional tableaus of maritime or landscape paintings in a collage of overlapping tropes and details. In , the details allude to larger patterns that each individual painting refuses to realize. In much the same way that Zong! leaves blankness on the page, Chaney points to non-representation beyond its frames. The pieces invoke patterns that play out in the imaginary wings of the painting, off-stage—much like the unrecorded stories that flow around the archive.

In another example of comparative relativism, Cherene Sherrard-Johnson presents a trans-disciplinary reading of Chaney in relation to Yanique’s novel The Land of Love and Drowning and Wangechi Mutu’s video art, emphasizing a “shared artistic vision that both generates and draws upon a dynamic archive that reshapes and reorients prevalent tropes of the region” among which she includes “debris” (Sherrard-Johnson Citation2019, 114). Debris is precisely what is repurposed in Chaney, in the sense that the artist’s eye recognizes cast-off breakage as material historical evidence. The paintings themselves appear complete in the sense that the fragment occupies the entire space of the board on which it is painted; the floating flowers pull the painting in toward itself, into the unique world within its frame. Similarly, the many geometric flourishes of the paintings claim their own space as historical remnants and materialize the fragment as a component of identity in a region that has for centuries been a crossroads of languages, religions, and cultures drawing from five different continents, most importantly Africa. The region’s very geography stipulates the importance of the fragment, whether theorized as part of a mosaic of landscapes and cultures by Edouard Glissant (who also prefers the fragment as a mode of critical discourse in his writing), or in its “archipelagic” integrity by Sherrard-Johnson, who argues that Virgin Islands art and literature “participates in interisland exchange based on circuits forged by colonial practices, dynamically revised through global black freedom struggles taking place in the islands and continents that form their diasporic communities” (Sherrard-Johnson Citation2019, 93). Belle’s own subtitle, “we live in the fragments” clearly centers the importance of the fragment as an essential vehicle of Caribbean expression. The fact that Belle presents her panels in relation to one another, in an iterative series, emphasizes the discreet specificity of each painting and the fact that the panels do not cohere into a single, larger pattern. And yet, the relational motifs do centralize the specificity of Denmark’s presence in the Virgin Islands.

That is, European porcelain from various countries and traditions found its way to the Caribbean but Belle’s Chaney series focuses on the blue and white pieces that allude to a specific Danish institution, the 250-year old Konglige Porcelainsfabrik, or Royal Copenhagen Porcelain Factory. The Royal Copenhagen brand came into being and developed in tandem with the Danish colonial period. In much the same way that Zong! transforms an original English text, Belle’s Chaney foregrounds Virgin Islands transformations of Danish source material. Both writer and artist create through the breakage of the colonial archive, and both indicate its ruination on multiple levels.

Counter-canonical art

Royal Copenhagen is not just any Danish product; it is, rather, a canonical Danish art form in the sense that it is universally recognized within the country as a fixture of Danish aesthetics and identity. Its history goes back to the blue and white china that originated centuries earlier in China and made its way to Europe in the 18th century, at the height of European imperialism. This is not a coincidence: the use of china was necessitated by the products of empire and trade. The influx of colonial items like coffee and tea, both augmented by the Caribbean product of sugar, altered daily practices in Europe. Whereas drinking vessels had for centuries been fashioned out of wood, metal, or leather, these were most suitable for beverages which were consumed at room temperature. Hot beverages like coffee and tea, imported from Africa and India, were best prepared and consumed in porcelain. Indeed, John Esten notes that “In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the drinking of tea became inseparably linked with blue and white china as the quintessential expression of English life” (Esten Citation1987, 123). Similarly, Mikkel Venborg Pedersen, in his book Luksus [Luxury], ties the rise of consumer culture in Denmark directly to the colonial period, pointing out that domestic space became a site of status at this point because “I hjemmene kom der flere genstande, og der kom ting og sager fra den store verden … eksotiske varer” [Homes became filled with more objects, and things from all over the world … exotic goods] (Pedersen Citation2013, 9). He, too, points out that the colonial period marked a transition in most households by which “tinbægre erstattedes af glas og porcelæn til at rumme eksotiske vin, kaffe, te og chokolade” [tin cups were replaced by glass and porcelain to contain exotic wines, coffee, tea, and chocolate] (Pedersen Citation2013, 32). Thus, it was no accident that the Royal Copenhagen porcelain factory came into being in 1775 when Denmark had just established sugar plantations in the Virgin Islands, for sugar was an enormous part of new imperial cuisines and beverages alike. The 18th century also saw a transition in dining practices from the more communal table servings of earlier periods to tables decked by individual place settings and porcelain (and sugar)figurines. Art historian Robert Finlay notes that, in the 18th century, “like palaces and ermine robes, massed displays of ceramic functioned as assertions of power and magnificence. Porcelain became the currency of social emulation among the aristocracy of every nation and spread down the social ladder to prosperous burghers and country gentry” (Finlay Citation1998, 172), which explains what it was doing in Caribbean colonies.Footnote12 Europeans asserted their power and advertised their wealth by bringing over porcelain. Again, “china” and “money.” The fact that these symbols of colonial power now wash up in broken bits almost seems like the landscape itself doing counter-archival work. As a character muses in one of Yanique’s stories, “One of my many teachers once said that history has no influence on land, that land is outside of history. He lied or he was mistaken. History has carved down mountains. History has drenched out rivers. History has made the land, and the land has, when under duress, made history” (Yanique Citation2010, 157, my emphasis).

Royal Copenhagen, Delft, Wedgewood, Willow, and other prominent brands of European porcelain dominated the market, with Willow becoming one of the most widespread china patterns to this day, but Belle’s art singles out the symbolism and significance of Royal Copenhagen fragments. In so doing, she dismisses the linearity of postcoloniality, a word predicated on a progressive pre-to-post shift in time, to assert instead an ongoing trans-Atlantic entanglement. Globally recognized and a national institution, Royal Copenhagen is a prominent Danish brand and therefore a sharp symbol of Denmark’s colonial presence in the Caribbean. As Belle notes in an interview, “Their patterns are legendary and very much a part of the Danish ethos. There is a particular way you paint them, those trained spend years learning” (Belle and Wilson). In another example of Royal Copenhagen’s centrality to Danish culture, the company is the source of a national tradition through its annual unveiling of a collectible Christmas plate. Yet another addendum to its centrality to Danish identity is its renowned Flora Danica series, a 1,351-piece project produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that was designed to enshrine the botanical life of Denmark on china bearing paintings of each individual specimen that grew on its shores. Porcelain was thus the medium for a discreet project in national portraiture and Flora Danica a canonical expression of national identity.

Chaney, the actual pieces found in the Virgin Islands, form organic counter-archival objects that Belle makes into tidalectic art, as Kamau Brathwaite theorized this concept: “tidalectics” refashion the linear and conclusive pattern of the European dialectic into a circular and mutually affecting pattern of signification. As Elizabeth DeLoughrey explains, tidalectics invoke “the continual movement and rhythm of the ocean … [and] foregrounds alter/native epistemologies to western colonialism and its linear and materialist biases” (DeLoughrey Citation2007, 2). Chinedu Nwadike adds to DeLoughrey’s understanding of tidalectics as a “geopoetic model of history” that the concept provides “the framework for exploring the shifting and complex entanglement between sea and land” (Nwadike Citation2020, 59). As Yanique’s character observes, landscapes possess memories, and the entanglement of water and land is also what reveals the pieces of chaney with which Belle works, washed out of the ground as they are by water. Moreover Chaney, the artwork, traverses the Atlantic, placing the broken shards of European china still embedded in the landscape of the Virgin Islands in dialogue with the Danish artistic tradition of Royal Copenhagen china and enacting, through Belle’s international projects, an ongoing washing-up of Danish culture on Virgin Islands shores and her routing of those artifacts back to Denmark—and, for that matter, to the USA, the latter-day and current territorial power in the Virgin Islands. Belle’s exhibits in both countries re-introduce otherwise marginalized Caribbean histories into such seats of (former) imperial power as Denmark’s Royal Library, in the case of the centennial exhibit (Blinde vinkler/Blind Spots) featuring Chaney and, as recently as the fall of 2020, Brookfield Place in New York. Situated in cozy proximity to the headquarters of Goldman Sachs and just blocks from Wall Street, Brookfield Place is the shopping mall of the 1% (as my colleague put it).Footnote13 Its high-end boutiques overlook the Hudson River and New York Harbor; its marbled galleries and indoor “winter garden” of palms exude wealth. The large paintings of Chaney in the halls of Brookfield Place thus brought the Virgin Islands into a symbolic and literal heart of American commerce, signaling and challenging the colonial legacy of both Denmark and the U.S.

While the Danish allusions in Chaney may not have been readily visible to viewers in its U.S. setting, their clear legibility in a Danish context is integral to Belle’s tidalectics. The mutual and ongoing influence of Danish and Virgin Island art forms, as it is manifest in Chaney, is evident in the role and force of recognition that is integral to both my comparative method (as it relates to my idea of wreckognition) and to the series itself. In terms of method, there is a mutual recognition between Zong! and Chaney of the archive’s failures and fissures, and a mutual emphasis on the power of the fragment to express the dynamics of Caribbean history. In terms of Chaney, Belle explains the importance of recognition in Helle Stenum’s film about Danish colonial history, We Carry It Within Us. Speaking of her art, Belle recounts wandering into the Royal Copenhagen porcelain shop in Copenhagen where, in looking at displays of the brand’s blue and white plates she realized, “Wait a minute—it’s chaney!” (Stenum Citation2017). And, in a beautifully symmetrical anecdote, the Danish researcher Camilla Lund Mikkelsen writes about taking her mother to the Royal Copenhagen Library exhibit in which Belle’s Chaney was featured. Mikkelsen’s mother took one look at Chaney and exclaimed, “Hov—det er jo musselmalet!” (46) [“Wait, that’s Royal Copenhagen!”—using the specifically Danish term for the brand’s painted designs] (Lund Mikkelsen Citation2018). Just as Lambert’s emphasis on recognition and repair in Zong! translates to counter-archival artistic practices, Belle’s tidalectics work through forces of recognition both cultural and historical.

In another, related series, Belle paints chaney patterns onto dinner plates, thus evoking the formal chinaware of the Royal Copenhagen Company while again depicting it as it crashed onto colonial shores (). The fact that she completed this series in collaboration with Royal Copenhagen and at their invitation speaks to the ongoing trans-Atlantic influences that Chaney routes back to Denmark from the country’s earlier presence in the Caribbean. The plates have the wholeness of their material design, but unlike the symmetrical or complete figural paintings of the Danish series, Chaney layers breakage onto this whole. Speaking of these pieces during an interview she was generous enough to grant me, Belle noted that “A lot of people … try to do what archeologists do, they try to re-piece it together, and I don’t like that” (Belle and Johnson Citation2019). The focus is on the singular details hidden within larger representations of symmetry or recognizable figures and landscapes.

How are the Chaney series counter-archival in the same way that Zong! is? Jenny Sharpe’s argument about the poem could be made about Belle’s Chaney when she asks, “what if a literary work did not fill the archival gaps with stories but explored the meaning of silence instead?” (Sharpe Citation2014, 466). Indeed, what if an artistic work did not piece together colonial fragments but explored the meaning of their breakage instead? What if the art gestured toward what is beyond the frame, unrepresented? Both poem and art inspire these moments of recognition, when different spaces and histories suddenly dovetail in our affective as well as intellectual understanding. Uncanny in nature, moments of recognition feature the strangely familiar, the sudden overlap in postcolonial time of past and present.

And, as per the framework of comparative relativism, I would argue that in its counter-canonical elements Chaney does something not unlike the many works of Caribbean literature that answer back to various European canonical texts. Belle’s intentional address to the canonical tradition of Royal Copenhagen china resonates with Aimé Césaire’s Une tempete/A Tempest and Elizabeth Nuñez’s Prospero’s Daughter, Maryse Condé’s La migration des coeurs/Windward Heights, Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, and Derek Walcott’s Omeros to name but a few. These works reimagine and respond to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, and Homer’s The Odyssey, respectively. Belle’s plates painted with fragments of images interact with the established aesthetic of wholeness in both image and form that is exemplified in traditional lines of Royal Copenhagen plates to this day. Much like counter-canonical literary works, which are numerous enough to comprise an entire sub-genre of Caribbean literature, Belle’s art identifies a significant colonial art form and explores not only its influence and presence in the Caribbean, but the ways that art was transformed and repurposed within colonial space. Césaire breaks down a centuries-long tradition of representing Caliban as a “monster” by picking up on his heroic traces and presenting him as a pan-Africanist freedom fighter in his rejoinder to The Tempest while Nuñez, conversely, assembles all the traces of Prospero’s own monstrosity in her retelling of the same play in a Caribbean setting. Rhys chips one shard out of Jane Eyre—that of the maltreated Jamaican wife relegated to the attic and to the margins of the novel—and shows the integrity of Bertha Mason’s fragment of the narrative in its original Caribbean context. Chaney, too, eschews the internal logic of an institution and industry that has long reflected national histories and imaginaries to which Denmark’s West Indian connection was ancillary, appearing as it did in rare images of seafaring and exotica.Footnote14 The fragments revision aesthetic practices and values in a way that centralizes colonial history deeply within them.

Counter-archival creation

My interweaving of counter-archival and counter-canonical work is also meant to illustrate the porous boundary between archives and art, between fetishized records of the past and the fact that those records are animated only by critical and creative engagements with them. As I noted earlier with regard to Zong!, Philip’s poem is now part of the archive; her ability to hear the voices of ancestors and to affectively and through language present unrecorded human experience makes her work essential to any scholar of this historical event.Footnote15 Gregson v. Gilbert is permanently transformed by her intervention in this otherwise canonical legal text. For example, literary scholar Christina Sharpe draws upon Zong! as a critical framework through which to understand not only the past of the Black Atlantic, but the contemporary phenomenon of what she terms the “Black Mediterranean” (Sharpe Citation2016). Juxtaposing the eighteenth-century event and the legal language surrounding it with the twenty-first-century deaths at sea of African migrants and the dehumanizing journalistic language that describes them, Sharpe uses Philip’s poem as a means of tracking and challenging anti-Black racism as she encounters it in contemporary headlines and in archival research alike. Counter-archival literature and art in fact extend the historical record into a state of ongoing production. Works like Zong! and Chaney make aesthetic and affective contributions to historical understanding while shimmering in their own artistry.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to La Vaughn Belle for so generously granting permission to publish images of her beautiful art. I also want to thank her for the immense impact she has had on my understanding of archivally engaged art; the conversations we have had and the presentations she has given have deeply enriched and informed this article. I thank M. NourbeSe Philip for sharing her annual collective reading of Zong! this year through a virtual event that allowed so many of us to hear the voices, breaths, and songs of her poem. I thank the Camargo Foundation for providing a haven in Cassis, France during this pandemic year and for bringing me together with such an inspiring community of artists and scholars while I completed this piece.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Erica L. Johnson

Erica L. Johnson is a Professor of English at Pace University in New York. Her scholarly fields include Caribbean literature and cultural memory studies, and she is the author most recently of Cultural Memory, Memorials, and Reparative Writing (2018), which examines ways in which memory furnishes important source material to affect theory researchers as well as the relationship between cultural memory and public monuments. She has co-edited a number of volumes including Wide Sargasso Sea at 50 (2020) with Elaine Savory, Memory as Colonial Capital (2017) with Éloïse Brezault, and with Patricia Moran The Female Face of Shame (2013) and Jean Rhys: Twenty-First-Century Approaches (2015). In 2009 she published Caribbean Ghostwriting, the book that launched her ongoing inquiry into the distinctive body of counter-archival Caribbean literature and art that sustains cultural memory in the face of the colonial archive. She has published in such journals as MFS: Modern Fiction Studies, Meridians, Anthurium, The Journal of Caribbean Literatures, Biography, Contemporary Women’s Writing, and JNT: The Journal of Narrative Theory.

Notes

1. Indeed, a number of scholars of Danish colonial history including Olwig, Andersen, Temi Odumosu, Mads Anders Baggegård, Lill-Ann Körber, and Daniela Agostinho have noted the marginalization of colonial history in narratives of Denmark’s history. Nina Cramer writes about the important role I Am Queen Mary has played in prompting public awareness of colonial history in Denmark, saying that “Rather than viewing I Am Queen Mary as having a strictly corrective relation to the textual and visual perversions of the archive (as offering an ‘accurate’ representation to counteract the abundance of racist imagery in circulation), I find it fruitful to imagine the [artwork] as putting pressure on taken-for-granted notions of historical narration or illustration at large” (Cramer Citation2018, 152).

2. See La Vaughn Belle, Tami Navarro, Hadiya Sewer, and Tiphanie Yanique, “Ancestral Queendom: Reflections on the Prison Records of the 1878 Fireburn on St. Croix (formerly Danish West Indies),” on the importance of the term “queen” in discussions of the Fireburn.

3. For a full discussion of the counter-archive see Michael K. Wilson’s interview with Belle, “Visualizing Vocabularies of the Counter Archive: A Conversation with La Vaughn Belle.” October 2017. Lavaughbelle.com.

4. All of the translations of Danish language texts in this essay are my own.

5. “Wreckognition” is a term I have been working out elsewhere to theorize counter-archival work. Wreckognition maintains the comparative principle of recognition—the way texts recognize one another, the way critics recognize conversations among texts—while referring specifically to texts that address the colonial archive. A noun imbued with a verb, “wreckognition” regards the colonial archive as a dynamic, contested, and continually evolving record that folds in acts of recording, curation, destruction, and creativity. (This piece is planned to appear in a forthcoming book, Caribbean Crossroads, co-edited by Tegan Zimmerman and Odile Ferly.)

6. In illustration of the poem’s sonic nature, Philip has staged annual readings of Zong! that require multiple, simultaneous readers layering words over breath over song to spellbinding effect. The most recent reading, held via Zoom during the pandemic, can be viewed here: Zong!Global%20mailchimp%20email.pdf.

7. Interestingly and tellingly, the staged reading of Zong! 2020 comes to a close right before this final, faded section of the poem as though to recognize its illegibility.

8. And as Christiane Taubira argues, cultural memory is a human right. (“Le droit á la mémoire.” Cités 25.1 (2006): 164–66; “Mémoire, Histoire, et Droit.” Le Monde 15 octobre 2008.).

9. Thanks to the digitization and availability of these records, I can illustrate with an example how we, as users and interpreters, must of necessity read colonial archives contrapuntally. In the interest of materializing the otherwise theoretical concepts here, I offer a reading of documents pertaining to education in the Danish Virgin Islands in the early twentieth century. Not only was the curriculum telling, in its required elements of Danish history, Danish geography, and “Danish habits” (“St. Thomas School Guidelines,” 1911) and its emphasis on the study of (Protestant) religion along with handwriting, math, and needlework for children in St. Croix and St. Thomas, but the “skolereglerner” or school guidelines are also telling for what they do not actually say. A clear set of educational guidelines were issued on both islands in 1911 that traces a larger social reality that seems to run counter to the very premise of universal education that these documents espouse. For example, although school is supposed to be compulsory the guidelines open with a host of exceptions whereby children may be exempt from public education for reasons having to do with alternative private or religious schooling or, more prominently, employment obligations. The St. Thomas guidelines in particular privilege the role of the child’s employer, stipulating that “parents and guardians, masters, house-owners, employers and managers” must furnish information about school-aged children or be fined. There are special sections of the manual for children’s employers’ duties and it requires that the file on each child should include “its employment” status. As interpreters of these manuals designed to illustrate the structure of compulsory education, what we can see is that the children of St. Thomas and St. Croix were frequently laborers and sometimes students. The guidelines are not intended to illustrate the fact that young children were put to work and that their employment could supersede their education. And yet, it is abundantly evident that the educational system did not revolve around students’ needs or interests.

10. I am grateful to an anonymous peer reviewer for making this excellent observation.

11. Dionne Brand and Saidiya Hartman in conversation at Barnard College, 2018.

12. To this day, china cabinets are fixtures of middle and upper-class households across the Atlantic, a tradition that speaks to the longstanding role of china/porcelain in representing class status.

13. Thanks to my colleague Dr. Phil Choong for this apt description of Brookfield Place!

14. Belle spells out the tangential presence of the Virgin Islands in Royal Copenhagen images in her series Collectibles, in which she takes these images from the original china and paints them onto white paper plates in blue paint.

15. Philip made clear in the 2020 annual public reading of Zong! that it was as much ritual as literary event, as much a tribute meant to the summon the ancestors as celebration of her own poetic accomplishment.

References

- Andersen, A. N. 2017. Ingen udskyldning: Erindringer af Danskvestindien og kravet om erstatninger for slaveriet. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Azoulay, A. A. 2019. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Brooklyn: Verso.

- Bastian, J., J. A. Aarons, S. H. Griffin. 2018. Decolonizing the Caribbean: An Archives Reader. Sacramento: Liberty Juice Press.

- Bastian, J. A. 2003. Owning Memory: How a Caribbean Community Lost Its Archives and Found Its History. Santa Monica: Libraries Unlimited.

- Belle, L. V. Lavaughnbelle.com

- Belle, L. V. and E. L. Johnson. 2019. Interview. October.

- Belle, L. V., T. Navarro, H. Sewer, and T. Yanique. 2019. “Ancestral Queendom: Reflections on the Prison Records of the 1878 Fireburn on St. Croix (Formerly Danish West Indies).” Nordisk Tidsskrift for Informationsvidenskab og Kulturformidling 8 (2): 20.

- Brand, D., and S. Hartman. 2018. Conversation at Barnard College, October 30. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mt-yRZgrCOw

- Caswell, M. 2021. Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work. New York and London: Routledge.

- Cramer, N. 2018. “I Am Queen Mary: An Avatar in the Making.” Peripeti, 29–12.

- DeLoughrey, E. 2007. Roots and Routes: Navigating Caribbean and Pacific Islands Literature. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Esten, J. 1987. Blue and White China: Origins/Western Influences. Brown: Little.

- Finlay, R. 1998. “The Pilgrim Art: The Culture of Porcelain in World History.” Journal of World History 9 (2): 141–187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2005.0099.

- Lambert, L. R. 2016. “Poetics of Reparation in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!” The Global South 10 (1): 107–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/globalsouth.10.1.06.

- Lund Mikkelsen, C. “Postkoloniale Dialoger i Kunsten: En analyse af udstilligen ‘Blinde Vinkler’ i et transnationalt perspektiv.” Thesis, 2018.

- Nwadike, C. 2020. “Tidalectics: Excavating History in Kamau Brathwaite’s the Arrivants.” IAFOR: Journal of Arts and Humanities 7 (1): 59.

- Olwig, K. F. 2003. “Narrating Deglobalization: Danish Perceptions of a Lost Empire.” Global Networks 3 (3): 207–222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00058.

- Pedersen, M. V. 2013. Luksus: Forbrug of kolonier i Danmark i det 18. århundrede. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanums Forlag.

- Peterson, A. R., and K.-M. Simonsen. 2019. “Relationel Komparatisme: Komparatismes udfordringer og agens I globaliseret verden.” Kultur og klasse 127: 29–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.7146/kok.v47i127.114741.

- Philip, M. N. 2008. Zong! Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP.

- Sharpe, C. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke UP.

- Sharpe, J. 2014. “The Archive and Affective Memory in M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!” Interventions 16 (4): 465–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2013.816079.

- Sherrard-Johnson, C. 2019. “‘Perfection with a Hold in the Middle’: Archipelagic Assemblage in Tiphanie Yanique’s The Land of Love and Drowning.” Journal of Transnational American Studies 10 (1): 94–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.5070/T8101043942.

- Simonsen, G. 2017. Slave Stories: Law, Representation, and Gender in the Danish West Indies. Ârhus: Århus UP.

- Stenum, H., director. 2017. We Carry It Within Us: Fragments of a Shared Colonial Past.

- Wilson, M., and L. V. Belle. “Visualizing Vocabularies of the Counter Archive: A Conversation with La Vaughn Belle.” October 2017. Lavaughbelle.com

- Yanique, T. 2010. How to Escape from a Leper Colony.“Kill the Rabbits.” Minneapolis: Graywolf Press: 157.