ABSTRACT

In this article, researchers from the perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism investigate the methodological possibilities and challenges offered by multisensory interviews with Norwegian Art and Crafts teachers regarding their practice theories connected to woodwork with primary school children. Author 1 has visited eight different schools, conducting multisensory interviews with eight different teachers in their different woodworking spaces. The authors, in active dialogue with post-humanism and new materialism, articulate how the “bodyminded” researcher, woodworking spaces, the children’s wooden artefacts-in-process and the structures making up practice architectures for woodwork in Norwegian primary schools have real, meaning-producing agency for the teachers’ practice theories about their teaching knowledge during the multisensory interviews. Finally, the article serves as a critique of the dominant form of mainly verbal interviews in educational research and instead feeds into an embodied, new-materialistic and ecological view on learning, meaning-making, communication and researcher-understanding.

Introduction: starting a journey towards multisensory interviews as a research method

In this research project I am investigating teachers’ practice theories about teaching and learning processes in woodworkFootnote1 in Art and Crafts education in primary schools in Norway. In the process I have aimed at designing and trying out what I call multisensory interviews as a method to produce empirical material. In short, a multisensory interview is about understanding another person’s lived experience through a multisensory meeting around artefacts of importance for the topic of the interview: in this study, wooden artefacts made by primary school children. Artefacts and materials brought into the interview situation function as mediators of lived experience, in this case the teachers’ teaching experience, filtered through the lived bodies of myself and the interviewees. In the multisensory interviews I am interested in activating the teachers’ embodied memory (Østern, Citation2013; Parviainen, Citation1998; Sheets-Johnstone, Citation2009). It is through the embodied, sensory meetings with materials that I seek to understand the teachers’ practice theories (see Kemmis et al., Citation2014) and produce rich interviews and discussions. Based on a broad understanding of how learning is embodied and material, embodied engagement activating the senses in this study is seen as primary, not secondary, in the teachers’ and researcher’s meaning-making processes.

In this article, our focus is methodological and knowledge philosophical. We are focused on what knowledge the method of multisensory interviews can produce when looking at it from a philosophical position of post-humanism and new materialism. The research question guiding us through this article is:

How do multisensory interviews with some Art and Crafts teachers produce knowledge, understood from the perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism?

Our reason for seeking to answer this research question is to actively work on stretching out beyond the traditional interview, where verbal aspects are the main focus. As we have sensed other aspects than strictly verbal as meaning-producing during the multisensory interviews, we wish to investigate what attention to embodied, material, spatial and dynamic aspects of multisensory interviews produces. For this, the philosophical perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism seem appropriate. Further, we seek to focus on how multisensory interviews are productive, what they produce in terms of knowledge, rather than what the interviews are.

The production of empirical material

A short contextualization of the larger research project is needed, even though the focus in this article is methodological. The production of the empirical material in focus took place during eight school visits in the middle-northern parts of Norway. The methodological approach is micro-ethnographic (Postholm, Citation2010, p. 48), which means that I have had intense and rich, but short, visits in the field in focus: shorter than in conventional ethnographic studies.

In six of the eight schools I had the possibility to observe children (from age 6 to 12) working in class, and in all the schools I performed multisensory interviews with the teachers. The school visits varied in length, from two hours to a whole working day for the teacher. These school visits can best be described as sensory explosions. The sound of hammers, saws and drills in action at times was so deafening that ordinary speech was out of the question. The fine layer of wood dust sometimes hindered the writing of my observation notes. Despite the short time span of the school visits, the sensory traces they have left on/in me have been rich and important when it comes to giving me an experience of the different characteristics and qualities at work in the different schools. As a result, the empirical material produced consists of a variety of expressions; 1074 photos, 8 research journals, 181 minutes of video material, 6 observation logs, 640 minutes of audio material and 182 survey responses (the survey is mentioned here only for contextualization; see Maapalo, Citation2017 for analysis of the survey).

Post-humanism and new materialism – the agency and affordances of materials

Throughout the multisensory interviews I have been attuned towards how materialities, bodies at work and organisational structures, have agency (Bennett, Citation2010; Maapalo, Citation2017). This attention of mine to start with points towards me as researcher as an important agent for the understanding produced. The materiality (including materials, bodies at work and structures) has taken part in producing my understanding of the teachers’ practice theories together with the teachers’ languaging of their teaching practices (the “verbal” parts of the interviews) – languaging being a concept introduced by Sheets-Johnstone (Citation2009). This attention towards materiality and sensations during the school visits has drawn me towards the philosophical position of new materialism and post-humanism (Barad, Citation2007; Bennett, Citation2010; Braidotti, Citation2013; Coole & Frost, Citation2010; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation2013; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012; Wolfe, Citation2010). We understand post-humanism as a comprehensive philosophical movement, and new materialism as a branch under that.

In short, a post-human philosophical position, as we use it, means that a rational and detached closure of what it means to be human, with the emphasis on human consciousness, rationality, objectivity and detachment from the material world inherited from the Enlightenment, is destabilised. The human (here, the teacher, and ourselves as researchers) is understood as embodied (not only as “language”, but neither only as “biology” or “culture”) and as part of, and always interacting with, human and non-human bodies, nature, structures and systems. As Wolfe (Citation2010, p. xxiii) points out, we emphasise a non-reductionist relation between the phenomenon to be explained and the mechanism that generates it. The human, as a meaning-producing and languaging system, is not separated from, but firmly and inseparably embedded in, the material world with its materiality.

From post-humanism’s openness to embodiment and embeddedness in the biological and material world, the step towards the philosophical stance of new materialism is short. In this article, it means that we zoom in on the agency of materials, including bodies, especially on the material wood, woodworking spaces, woodworking pupils and teacher bodies at work and on practice architectures (Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008; Maapalo, Citation2017) that open up for or hinder woodwork in Norwegian primary schools. At the core of the philosophy of new materialism is the view that materiality is not passive (Coole & Frost, Citation2010, p. 1).

Central to us is the understanding that matter, or materiality, is not unimportant, separate from or detached from humans’ experiences, consciousness, thinking and languaging. The thinking and languaging capabilities of humans arise in concrete and direct relation to humans’ embeddedness in and interaction with materialities. For this study, it means that pupils, teachers and researchers are understood to act and think as material bodies intertwined with woodwork related materials. Materials, like wood, invite to action and interaction, and the materials, like wood, can be understood as active actants. Actant is a concept known from Latour’s actor-network theory, a social theory that includes humans and non-humans in equal ways (Latour, Citation1996, p. 2; 2004, pp. 76–77; 2005). Latour (Citation1996, p. 7) describes an actant as “something that acts or to which activity is granted by others”. In this article, in line with new-materialistic thinking, we seek to investigate how the teachers’ practice theories materialise in the multisensory interviews in complex, pluralistic and open processes that can be recognised as immersed with the agency of wood, woodwork and related structures.

We also would like to touch on the concept of affordance, which can be explained as meaning offer, since the concept has importance especially in a learning context. Gallagher (Citation2012, p. 168) writes about how Gibson (Citation1986), influenced by body phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty, developed the concept of affordance. In a learning theory context, especially Selander and Kress (Citation2010) have used the term “affordances” in developing their multimodal design learning theory. By the term affordances, Gibson (Citation1986, p. 127; original emphases) means “The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill.” Affordances can be understood as meaning offers that learners can act upon. Different learning materials or environments offer different learning opportunities, in a dynamic meeting with learners and the teacher. An outdoor education learning environment, for example, holds other affordances than an indoor classroom. The material wood holds affordances that only wood can offer. Wood as material for human-actants (Latour, Citation1996) affords endless possibilities for constructing numerous artefacts such as timber houses, tools, furniture, firewood, hunting equipment, and so on. The wooden materials offer “the maker” hard resistance, all depending on the density and humidity of the material at hand, and thus, when working with wood the human-actant (Latour, Citation1996) always has to use tools combining metals and other materials, in contrast to working with other materials such as clay or wool where lukewarm water and human hands can be enough.

In other words, the agency of wood shows itself as affordances, inviting children and the teacher into interactions that are framed by the affordances, or meaning offers, that wood holds. The idea of affordances is in line with a new-materialistic re-localisation of the human species, as not the only agent of the world, but instead as one agent among others within an environment, the material forces of which hold certain agentic capacities.

Embodied learning

To emphasise the importance of material artefacts, spaces and structures in connection to research interviews presupposes a broad understanding of learning and meaning-making that is connected to an epistemological shift often called the embodied, or corporeal, turn (Sheets-Johnstone, Citation2009). In her review of research about embodied learning, Anttila (Citation2013, p. 31) writes that, in short, embodied learning means that learning takes place in the whole body, within a person and between persons interacting in and with social and material realities. Theory on embodied learning shows that movement, thinking, affects and feelings are parallel and interdependent activities (Gallagher, Citation2012; Thompson, Citation2007). This study rests on that broad and holistic view of learning and meaning-making. As the teachers, pupils and I as researcher meet and interact with one another, and with spaces and wooden artefacts in this study, we do so as lived bodies. Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962/2002) understands the lived body as the vehicle of being in the world, and not only for being in the world, but also for understanding the world.

Multisensory interviews – analysing how they produce knowledge

Having introduced central philosophical perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism we now return to our research question:

How do multisensory interviews with some Art and Crafts teachers produce knowledge, understood from the perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism?

In this section, we seek to investigate how multisensory interviews produce knowledge. As we turn to the large empirical material at hand, we are guided by the bodymindedFootnote2 (Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012), lived experience (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962/2002) by Pauliina, who has conducted all the interviews. Lenz Taguchi (Citation2012, p. 43) writes about how learning situations – as research also is – take place in a flow between what is thought and what is felt, in a bodily-intellectual or bodyminded flow between material and discursive aspects. What Pauliina keeps coming back to, school visit after school visit, is how important it is for the interviews to be conducted in the spaces allowed by the schools for woodwork; to see, touch and centre the interviews around the materials and children’s’ artefacts; the different structures or practice architectures she senses and hears about, and finally – herself as a researcher oriented towards these aspects. These aspects start to single out as analytically important. In other words: in the interview situations space, materials and artefacts, practice architectures and the bodyminded researcher seem intertwined with the teachers as research participants. From a post-human perspective, we understand this as the human being (in this case the researcher) as always part of, and intra-acting with other bodies (human and non-human), nature, structures and systems.

“Intra-act” is a term used by Barad, indicating that those parts intra-acting are not separate and distinct subjects/objects (as in interaction), but intertwined and entangled. This understanding of the entanglement between researcher, materials, spaces, structures and human and non-human bodied during the multisensory interviews leads us to the concept of diffraction and diffractive analysis, used by Barad. With the analytical concept of diffraction Barad (Citation2007) seeks to show entanglements. In short, diffraction is oriented towards differences within a net of entanglements more than similarities. In this methodologically oriented analysis of the multisensory interviews, we understand this as an impulse not to be oriented only towards the verbal parts of the interviews, but to actively open up to other and different aspects that the languaged aspects of the interviews are interwoven with.

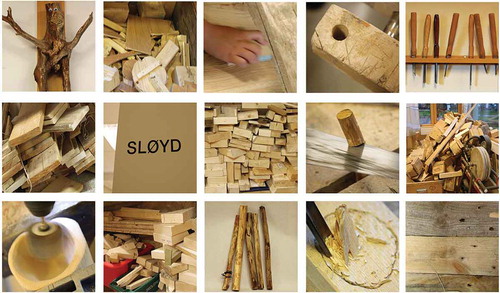

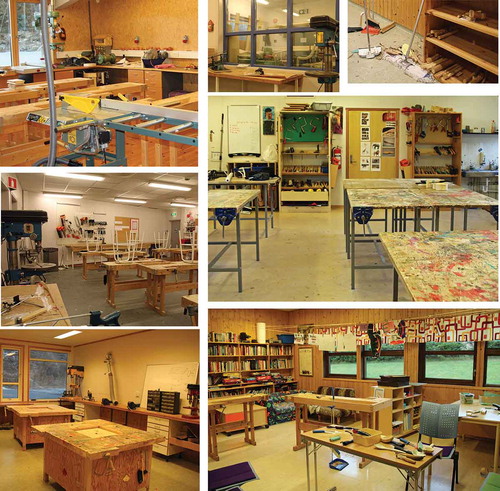

In the following, then, we seek to do a diffractive analysis, cutting through the large empirical material and “freezing” it at points that Pauliina’s bodyminded understanding of the multisensory interview situations has led us to. We could choose many different points to stop at, but the material is large, and we have to be selective. We have chosen to cut through a number of situations that seem particularly rich in displaying the analytical dimensions that we are carving out slowly through the diffractive analysis. These analytical dimensions/entanglements are woodworking spaces (see examples in photo collages 2 and 3), wooden materials/children’s wooden artefacts as actants (see examples in photo collage 4), the powerful agency of practice architectures and the bodyminded researcher acting as a binding web between all analytical dimensions.

We use the analytical dimensions that we are carving out through our diffractive analysis as subtitles in this section, in order to create a readable structure through our emerging analysis, except the bodyminded researcher. Instead, we allow this analytical dimension to flow through the whole diffractive analysis, entangled with the other aspects.

Woodworking spaces with agency

To be surrounded by, or be part of, the woodworking rooms served as the very foundation for the interviews. In this lies my intention of trying to “awaken” the teachers’ embodied memory through embedding the interviews into the woodworking spaces. In the woodworking space the teachers’ embodied memory, as well as my own, is put into play by the space itself, as the space itself has agency; it is an actant (Latour, Citation1996) that actually does something with the teachers and with me in a very real way.

With photo collages 2 and 3, we try to illustrate how woodworking spaces, materials and tools have agency and thus the ability to guide and inform pupils in their woodworking practices and teachers in developing their practice theories about woodworking processes.

The concept of space we see as consisting of various assemblages (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation2013, pp. 585–587), bundled together and forming an infinite amount of extensive and intensive multiplicities (p. 37). This assemblage of spaces exists in interconnected relations with other actants, human and non-human (Latour, Citation1996, p. 2; 2004, pp. 76–77) possessing both extensive properties (length, volume, height, etc.) and intensive properties (temperature, smell, density, humidity, etc.). These properties affect the experience of the persons involved in the interview conversation in the room at a deep bodily level.

Many parts of the interview conversations with teachers took place while walking around the woodworking facilities. Here and there the teachers would see something and take it in their hands and talk about it. I followed them around with my equipment,Footnote3 and tried to capture the whole experience of being in the rooms. The materials in the rooms seemed to guide and inform the course of the conversation. These kinds of encounters were physically active and more intense ways of multisensory interviews, but sometimes the teacher and I would just sit around a table and let stories emerge in a slower way by dwelling on the artefacts (see, for example, photo collage 4).

Wooden materials/children’s wooden artefacts as actants

Another, and very important, strategy for the multisensory interviews was to have the children’s wooden artefacts available in the space for myself and the teacher to touch, turn around, smell and look at from different perspectives. The sensory interview develops out of the sensory investigation of the artefacts. Kojonkoski-Rännäli (Citation2014, p. 1) writes that “it is through the hands that the most sensitive and multifaceted interaction with our surroundings takes place”. The kind of multisensory meetings with children’s wooden artefacts that have taken place in this study “involves the researcher self-consciously and reflexively attending to the senses throughout the research process, that is during planning, reviewing, fieldwork, analysis and representational processes of a project” (Pink, Citation2015, p. 10). The senses serve as one way to meaning-making, and the whole researcher body needs to be alert and wide awake, embodied and embedded in the biological, material and technological world. Here, the emphasis is on “the agentic contributions of nonhuman forces (operating in nature, in the human body and in human artefacts)” (Bennett, Citation2010, p. xvi).

Photo collage 4. Primary school children’s artefacts made of wood (also some textile and pieces of metal).

As I met the teachers, pupils, spaces and materials – in other words, the various “woodworking assemblages” (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation2013, pp. 585–587) – the wooden materials appeared in different temporal-historical phases in ongoing woodworking processes. In the following I will show some examples from multisensory encounters where the agency of materials and artefacts came forth in different ways. The fact that none of the teachers I met had any written plans to give their pupils made these encounters even more important.

In one of the schools I visited, the pupils were in the process of making ladles out of a willow tree that had been cut down in a forest behind the school. The teacher and I sat down for a long time while having these carved artefacts at hand.

Photo collage 5. Teacher holding and showing an artefact made by a child, while thinking about and explaining the teaching.

In this short sequence from a film clip shown in photo collage 5, the teacher shows parts of the working process by holding an artefact in her hands while pointing with her fingers at specific crucial parts of it and turning it around. Here, detailed information about the process can be seen as stored in the artefact itself, and the close physical contact can help in recalling it. As the teacher carefully studies the artefact with her fingers, sensing the different qualities of the surfaces, she is reading the wood with her hands. The teacher’s touch and the movement of her fingertips on the piece of the carved willow tree point out the basic strategy connected to teaching and learning in this particular process. Her pupils have to work their way in to the material while being able to hold on to the shape afforded by the tree/wood and with the help of a few crucial marks drawn using a template. As we have pointed out earlier, the human, as a meaning-producing and languaging system, is firmly embedded in the material world (Wolfe, Citation2010). Here, the material artefact is an actant informing the course of the discussion between me as researcher and the teacher. The talk is slow and filled with pauses and gaps, as if the hands, the artefact and the teacher’s whole body are in a slow dialogue with the artefact. In the situation at hand, and later when transcribing this multifaceted material, I as researcher “fill in” the sentences that lack words, with the help of the non-verbal communication stored in the audio-visual material as my own bodily memory is awakened by it.

The next examples illustrate multisensory encounters with a teacher who has many classes with pupils in different ages. Our aim is to point out how the teacher’s bodily engagement with two very different wooden materials is directly connected to his languaging of thinking about teaching and learning. Theory on embodied learning shows how activities like movement, feelings, affects and thinking are parallel and interdependent (Anttila, Citation2013; Thompson, Citation2007).

Photo collage 6. A teacher languaging his thinking with a wooden piece of pine as actant and affordance for his thinking.

In the film clip shown in photo collage 6, the teacher takes out wooden pieces from a shelf in a storage room. He holds a piece of pine in his hands, turns it around, lets his palm slide up and down over the roughly polished piece, producing a shuffling “zz-zz” sound – like a musical instrument.

I ask the teacher: “You said something about the planing … that the wood pieces are already planed?”

Teacher: /…/Yes they are planed, we work with pine that is pre-planed, everything is outright? … so they [the pupils] get to experience that as well … here it is about the accuracy of measuring, things we try to exercise, like, of course, knowledge connected to using tools and that kind of thing/…/

A planed pre-dimensioned board affords (Gibson, Citation1986) the students with learning opportunities connected to accuracy in woodworking processes, something the teacher seems to be very aware of. As his hands touch and play with the planed pine pieces, his thoughts about teaching and learning strategies for students in different phases of their learning trajectories in woodworking emerge as words and gestures.

The next sequence (photo collage 7) illustrates how the same teacher goes on with studying other kind of wooden material qualities as we talk. The teacher compares the differences between experiencing working with the pre-planed pine pieces and the very organic “unpolished” alder wood.

The teacher says:

/…/this is a tree that was cut down a few years ago … so it is a part of the “wood-experience”… they [the pupils] feel the scent … they feel the scent … there is a scent here … and you get a totally different [experience] … it has been fantastic to work with it because it has almost like an oak quality with regard to both the scent and hardness and colour, so it is very sculptural … now there is some blue mould in it, and when you polish it, they [the pupils] get different shades and they see that it goes all the way through the wood here. This is the ageing process, so it becomes a part of the “wood experience/…/”

This clip illustrates again how the teacher’s emerging practice theories of teaching and learning processes seem to be deeply embedded in the material at hand. As the teacher interacts with it as a lived body (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962/2002) he opens up his understanding of it. This is in line with Coole and Frost’s (Citation2010, p. 1) emphasis on acknowledging the power of matter in our ordinary experiences. In this case the pre-planed pine pieces and the more “amorphous” pieces of alder wood have agency in the sense that they afford several possibilities. They afford the teacher with sensuous impulses, awakening his bodily memory, and they provide his pupils with various learning opportunities. The organic, amorphous shapes and various sensuous qualities of the alder wood are something this teacher sees as a part of this specific teaching and learning process, which includes engaging the pupils in the slow process of bodily experiencing the change where green moist wood from the forest becomes dry and changes colour as the qualities it provides the pupils with change as well.

Wooden materials and children´s wooden artefacts as actants is an analytical dimension that has enlightened our understanding of the embeddedness of knowledge in bodies (Anttila, Citation2013), human and non-human (Latour, Citation1996, p. 2; 2004, pp. 76–77).

The powerful agency of practice architectures

In a previous analysis (Maapalo, Citation2017), within the same comprehensive research project as in this article, I focused on contours of practice architectures that enable and constrain woodworking practices in the subject of Art and Crafts in Norwegian primary schools by using the theory of practice architectures developed by Kemmis and Grootenboer (Citation2008) as lenses. The theory of practice architectures shows how practices are composed and made possible through different arrangements that hold them in place, and it is useful when one is trying to identify enabling or/and constraining aspects in practices (see also Kemmis et al., Citation2014). Through the analysis conducted, I constructed building blocks in a practice architecture for woodworking practices in primary school. The building blocks at work in this study were defined as competence; spaces and materiality; teaching integrity; the interaction between pupil engagement and teacher dedication; and tradition. We understand these building blocks of practice architectures as having agency that affects the teachers’ emerging practice theories about teaching and learning in woodworking practice. This was also evident in the multisensory interviews in various ways.

The study, involving among others an analysis of a survey (Maapalo, Citation2017), revealed major differences among the teachers in the study regarding competence in Art and Crafts, and especially in woodworking. This picture is supported by larger mappings done of the field (Espeland et al., Citation2013). The results of Maapalo’s study indicate that even informal competence and interest in woodworking seem to be, at the moment, crucial preconditions for the existence of woodworking practices in some Norwegian primary schools today. This is so because many teachers lack formal competence in Art and Crafts (see Maapalo, Citation2017).

In this article, with focus on multisensory interviews, we have discussed some examples where the materials and artefacts enrich the interview as the teacher’s embodied memory is awakened. These examples come from encounters where the building blocks of the teacher’s competence and space and materiality interact in a way that also fuels the conversation, as in the example where the teacher’s practice theories showed themselves as deeply embedded in the various materials, planed pine wood pieces and amorphous alder wood pieces. Here, the teacher had long experience of teaching in general and a personal interest in woodworking, although he had little formal competence in woodwork. The wooden materials and woodworking traditions he was deeply engaged with seemed to have powerful agency in his teaching practice. He enjoyed his teaching integrity, showing itself as being afforded with the possibility of having a deciding role over the use of woodworking spaces and time schedules. This integrity in making teaching choices did not come by itself, but was rather a result of the teacher’s dedication and informal competence in woodwork.

The building blocks of interaction between pupil engagement and teacher dedication and tradition create a kind of supporting skeleton in the practice architecture for woodworking practices. The pupils’ engagement (awakened by the agency of wooden materials) awakes a response in the teacher, since the teacher observes that the woodworking has meaning for the pupils, and sometimes the teacher’s dedication (actualised, for example, in the effort of acquiring various materials) awakes a response in the pupils. An interactive loop between teacher and pupils starts, and feeds itself through the affective elements of dedication and engagement. During the interview with this particular teacher, the whole practice architecture he was affected by was in play and mattered as an actant for the interview itself.

As the teacher and I walked in the spaces filled with wooden artefacts in different phases of becoming, the agency of practice architectures geared up the multisensory interview. We were actually walking in an architecture consisting of visible and invisible structures, and the architecture served as an assemblage of spaces (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation2013, pp. 585–587) informing our conversation. This teacher literally had something to touch and to tell due to the fact that he was an actant in a network of practices where he had the agency to enable it despite some rather large challenges and constraints (see Maapalo, Citation2017). Also I as researcher was clearly an actant in our meeting with each other, the spaces and materials.

With this example – one of many possible examples in the empirical material – we wish to show the powerful agency of the interaction between the different building blocks in the practice architecture (Kemmis et al., Citation2014) emerging in the conversations. A change in one building block – for example, access to space and materials – will affect another building block – for example, the teaching integrity – and thus will have agency on the richness of both the answers and the questions in a multisensory interview.

Concluding discussion

In order to make sense of the meaning-producing, sensory explosion I experienced as a researcher during the eight school visits in this study, we have in this article tried to make connections between the method of sensory interviews developed and a relevant philosophical approach, led by the research question:

How do multisensory interviews with some Art and Crafts teachers produce knowledge, understood from the perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism?

As we approach the end of our investigation, the insight we have come to and thereby our answer to the research question is that it is through the perspectives of post-humanism and new materialism (Barad, Citation2007; Bennett, Citation2010; Braidotti, Citation2013; Coole & Frost, Citation2010; Deleuze & Guattari, Citation2013; Wolfe, Citation2010) that the multisensory interviews produce knowledge that can challenge the traditional, verbally oriented research interview and open up more multisensory research possibilities. The analytical approach that has helped us is Barad’s diffractive analysis, where we cut through and freeze certain points of the ongoing, entangled flow of knowledge production, allowing us to show how different aspects of the flow have agency for the interviews. Our tentative answer to the research question thereby is: It is through a diffractive analysis, seeking to show differences and entanglements, that multisensory interviews can produce knowledge in dialogue with post-human and new-materialistic philosophical perspectives. Without the dialogue with a post-human and new-materialistic understanding of the human being, learning, meaning-making and communication as fully embedded in and interacting with human and non-human materialities with agency, the multisensory part of the interview would easily have seemed like only a minor addition to the verbal interviews. Now, instead, we have articulated, in active dialogue with post-humanism and new materialism, through diffraction, how the woodworking spaces, the children’s wooden artefacts-in-process, the structures making up practice architectures, and the bodyminded researcher have real, meaning-producing agency for the teachers’ practice theories and languaging of their teaching knowledge during the multisensory interviews, as well as for the researcher’s emerging knowledge construction.

We wish to suggest that our main knowledge contribution with this article is in supporting a broad and holistic view of learning, meaning-making and communication as a base for the development of research methods in education, particularly in arts education, and specifically in Art and Crafts education. In this case, this concerns teachers’ practice theories and meaning-making about their own woodwork teaching, as well as the researcher’s possibility to obtain a full and whole understanding of the complexity and richness of the educational phenomenon she is studying. In dialogue with post-human and new-materialistic authors like Barad (Citation2007), Lenz Taguchi (Citation2012), Wolfe (Citation2010), Coole and Frost (Citation2010) and Latour (Citation1996), we have highlighted how the meaning-making of the teachers and the researcher during the multisensory interviews in this study always and deeply takes place through its embeddedness with human and non-human materials, bodies and structures. Throughout, we have sought to connect and contribute to a learning, meaning-making and research view that is embodied and new-materialistic. The view of the centredness of cognitive, verbal and detached teacher-thinking, and researcher-understanding is destabilised.

With this article, we also lean on and support the meaning of the concept of affordance, which especially Selander and Kress (Citation2010) have used in connection to learning. Different learning materials or environments offer different learning opportunities in a dynamic meeting with learners and the teacher (and researchers). Wood as material for human-actants (Latour, Citation1996) affords endless possibilities of experiencing sensuous and intensive properties like densities, colours and humidities, with an equally endless list of constructing affordances like artefacts made by children as in this study, tools, furniture, firewood and hunting equipment. In the research material producing the multisensory interviews investigated in this article, wood as a material has had vivid agency, directly feeding into the teachers’ practice theories and languaging, and my own understanding as researcher.

These multisensory interviews were bodily demanding for me as a researcher and required my full attention, although the level of intensity varied. The materials and artefacts seemed, as shown in this article, to give memory impulses to the teachers. The multisensory interviews were fuelled, energised and enriched by the powerful actants present in the rooms. Stories about teaching and learning emerged, one after another, as new actants called upon us. As Pink (Citation2015, p. 28) wrote, in doing sensory ethnography, or, as here, multisensory interviews, “the experiencing, knowing and emplaced body” is the pivoting point. During the multisensory interviews I mostly did not directly ask the teachers about their teaching and learning philosophies, although I had noted a few pre-planned questions as a checklist mostly for myself. The embodied encountering with human and non-human actants (Latour, Citation1996) and the complex material assemblages I encountered held agentic capacities affording me questions. These questions took shape as I sensed the woodworking spaces with all their materiality, observed the pupils working with tools and different wooden materials, and followed the teachers while they were telling their material stories in these multisensory encounters. As a researcher and a visitor in the schools I shaped many of my questions at the very moment at hand. These questions emerged directly as a result of bodily interaction with the situation. So, as much as the artefacts, the materials and the rooms were actants that informed the teachers’ practice theories in the interview situations; they also had agency in shaping my interview questions in the course of the situation at hand.

A critical view of our own study tells us that to produce research material through school visits and multisensory interviews also has its limitations and pitfalls. It is very time- and energy-consuming, and the researcher meets with complex, often chaotic situations, where the level of presence needs to be high throughout. There is a lot of equipment to manage, and many ethical considerations to take into account regarding the nearness the researcher is given to pupils, their artefacts-in-process, the teacher, schools and structures. While acknowledging that this kind of research methodology does not suit every researcher, and that it is only complementary to other kinds of studies, we still argue that multisensory interviews as a research method hold the affordance of complementing with a deeper understanding of the materialistic and embodied dimensions of teachers’ practice theories in woodworking practices. As we perhaps manage to lay a fine floating layer of dust, wooden artefacts and complex embodied and material agentic structures over the article, we suggest that in the analysis undertaken, the teachers’ practice theories and the researcher-understanding have shown themselves as part of a pedagogical and materialistic ecology, rather than as detached and separate parts.

Finally, our investigation of the multisensory interviews from a post-human and new-materialistic perspective might serve as a critique of the dominant form of mainly verbal interviews in educational research. We suggest that multisensory interviews can produce research situations and materials that can give the researcher a rich understanding of the phenomenon in focus, in this case the agency of wood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pauliina Maapalo

Pauliina Maapalo is a PhD candidate, Art and Crafts teacher and teacher educator at Nord University, located in Nesna, Norway. She is currently working on her doctoral thesis and is especially interested in developing learning/teaching processes focusing on woodwork and questions connected to ecology/sustainability.

Tone Pernille Østern

Tone Pernille Østern, Dr of Arts in dance, is professor in arts education with focus on dance at the Department for Teacher Education, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. She is head of the section for Arts, Physical Education and Sports, and leader of the Master’s Degree Programme in Arts Education.

Notes

1. In this article I use the concept of woodwork. Historically in Norway the word sloyd has almost been synonomous with woodwork (Kjosavik, 2001; Thorsnes, Citation2012) and still “lives” in the Norwegian language; for example, in teachers’ sayings and as signs on doors. In general, in the Nordic context sloyd refers to a wider use of materials and complex processes of “making”. About sloyd-related research, see, for example, Hartvik (Citation2013) and Johansson (Citation2002).

2. The concept of “body-mind” was first developed by, among others, John Dewey in an academic context (see, for example, John Dewey, the Later Works (Dewey, 1981, pp. 199–225), but has also been used widely and for a long time in somatic practices such as yoga, pilates and dance. It is beyond the scope of this article to trace the histories of the concept of bodyminded, or even to define it properly. Here, we simply use the concept to emphasise a view on body-and-mind as one inseparable unit.

3. Camera, video camera, digital voice recorder, pen and paper.

References

- Anttila, E. (2013). Koko koulu tanssii! Kehollisen oppimisen mahdollisuuksia kouluyhteisössä [The whole school dances! The possibilities of embodied learning in a school context]. Acta Scenica 37. Helsinki: Teatterikorkeakoulu.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Coole, D., & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialisms. Ontology, agency, and politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2013). A thousand plateaus. London: Bloomsbury.

- Dewey, J. (1981). Nature, life and body-mind. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey the later works, 1925-1953. Volume I: 1925 (pp. 191–225). Carbondale: Southern Ilinois University Press.

- Espeland, M., Arnesen, T. E., Grønsdal, I. A., Holthe, A., Sømoe, K., Wergedahl, H., & Aadland, H. (2013). Skolefagsundersøkelsen 2011 [School subject study 2011]. Retrieved from https://brage.bibsys.no/xmlui/handle/11250/152148

- Gallagher, S. (2012). Phenomenology. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gibson, J. J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. New York, NY: Psychology Press Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hartvik, J. (2013). Det planlagda og det som visar sig: Klasslärerstuderandes syn på undervisning i teknisk slöjd [That which is planned and that which emerges: Class teacher students’ view of teaching technical sloyd] ( Doctoral thesis) Pedagogiska fakulteten, Åbo akademisk förlag, Åbo.

- Johansson, M. (2002). Slöjdpraktik i skolan hand, tanke, kommunikation och andra medierande redskap [Sloyd practice at school, hand, thought, communication and other mediating tools] (Doctoral thesis). Göteborg, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. 10.1044/1059-0889(2002/er01)

- Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating praxis in practice: Practice architectures and the cultural, social and material conditions for practice. In S. Kemmis & T. J. Smith (Eds.), Enabling praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 37–62). Rotterdam: Sense.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer.

- Kjosavik, S. (2001). Sløjdens utvikling i Norge 1860-1997 [The development of sloyd in Norway 1860-1997]. In I. C. Nygren-Landgärds & J. Peltonen (Ed.), Visioner om slöjd och slöjdpedagogikk. Forskning i slöjdpedagogikk och slöjdvitenskap B:10/2001. Techne Serien [Visions about sloyd and sloyd pedagogy. Research in sloyd pedagogy and sloyd science B:10/2001. Techne Serien] (pp. 166–193). Vasa: NordFo.

- Kojonkoski-Rännäli, S. (2014). Käsin tekemisen filosofiaa [The philosophy of working with the hands]. Turku: University of Turku.

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory. A few clarifications plus more than a few complications. Soziale Welt, 47(4), 369–381.

- Latour, B. (2004). Politics of nature – How to bring the sciences into democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2012). Pedagogisk dokumentation som aktiv agent. Introduktion till intra-aktiv pedagogik [Pedagogical documentation as active agent. Introduction to intra-active pedagogy]. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Maapalo, P. (2017). “Vi rigger til så godt vi kan” – Konturer av praksisarkitekturer som muliggjør og hindrer undervisning i materialet tre i kunst- og håndverksfaget i norsk barneskole [“We rig up as well as we can” – Contours of practice architectures that enable and constrain woodworking practices in the subject of arts and crafts in Norwegian primary school]. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 1(1), 1–20.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962/2002). Phenomenology of perception. ( C. Smith, Trans.). London: Routledge.

- Østern, T. P. (2013). The embodied teaching moment: The embodied character of the dance teacher´s practical-pedagogical knowledge investigated in dialogue with two contemporary dance teachers. Nordic Journal of Dance, 4(1), 28–47.

- Parviainen, J. (1998). Bodies moving and moved. A phenomenological analysis of the dance subject and the cognitive and ethical values of dance art. Tampere: Tampere University Press.

- Pink, S. (2015). Doing sensory ethnography (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Postholm, M. B. (2010). Kvalitativ metode: En innføring med fokus på fenomenologi, etnografi og kasusstudier [Qualitative method: An introduction with focus on phenomenology, ethnography and case studies]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Selander, S., & Kress, G. (2010). Design för lärande – Ett multimodalt perspektiv [Design for learning – A multimodal perspective]. Lund: Norstedts.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2009). The corporeal turn. An interdisciplinary reader. Exeter: Imprint Academic.

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life. Biology, phenomenology and the sciences of mind. England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- Thorsnes, T. (2012). Tresløydhistorie – Fra hendig til unyttig? [History of wood sloyd – From handy to unuseful?]. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag.

- Wolfe, C. (2010). What is posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.