ABSTRACT

Recent development in policy and learning theory encourages higher education institutions to send their students out of campus and into work placements. In this paper, we report on students’ engagement with various aspects of knowing through practice in work placements. We employed focus group discussions to gather students’ accounts of their knowing in the three higher education programmes: Teacher Education, Aqua Medicine, and Music Performance. The students’ accounts of knowing were analysed as personal epistemologies. Thereby, we aimed to focus on how enacted practices in work develop students’ appraisals of knowing and subjectivities. Three prominent epistemologies were present across all three student groups: professional judgment, professional practice, and professional identity. After the work placements, the students better understand how to enact their knowledge and what knowledge to pursue further. Based on these findings, we hold that there are key educational processes that arise in the interplay between students’ situated enactment of practices, knowing, and personal epistemologies through work placements, and propose a conceptual model to frame students’ learning in work placements.

Introduction

In recent years, work placement learning has received renewed policy focus internationally (e.g. OECD, Citation2017). Increased integration has taken place in traditional professional programmes, such as in university and hospital collaboration in health care (Kennedy et al., Citation2015). In other academic disciplines, such as biology, these advances in integration between teaching in university campuses and in workplaces are salient (e.g. Parker & Morris, Citation2016; Trede & McEwen, Citation2015).

The role of work placements to prepare students for employment (Billett, Citation2015) and add to learning (Crebert, Bates, Bell, Patrick, & Cragnolini, Citation2004), and the unique situated contributions to their learning that can be facilitated through work placements, have garnered increasing support (Billett, Citation2014; Helyer, Citation2011). Thus, higher education institutions are seeking further avenues through which students can partake in society and work as part of their education. However, how working experiences contribute to students’ learning is yet not fully understood, though several theoretical perspectives have been employed to explain these (Billett, Citation2017). There are myriad of experiences particular to specific workplaces, and a myriad of subjectivities that encounter them. What in particular “work experiences” contribute with across different study programmes is therefore challenging to capture in any one theoretical model.

Research question

We examine three education programmes, Aqua Medicine (AM), Teacher Education (TE), and Music Performance Education (MPE). Particularly, we examine the way in which students within these varied programmes discuss personal epistemologies in relation to their work placements. Hence, we use the disparate programmes to better understand variations and common themes across experiences in different study programmes.

We address the following research questions: What are the students’ accounts of personal epistemologies in relation to their work placement experiences? What are common themes and variations that emerges across the education programmes? Based on the results, we aim to define the core learning activities in a work placement.

Knowing and personal epistemologies in work placements

As work placements are increasingly emphasised as a general tool by which to achieve important aims for education, a general notion about knowing in conjunction with these experiences must be developed. To examine students’ learning in work placements, we position our approach by drawing on practice-theory and recent advances in personal epistemologies in work. Practice-oriented theorising of learning (or knowing), has advanced that individuals learn as they engage with practices and integrate into working communities (Brown & Duguid, Citation1991; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Gherardi (Citation2009a) argues that workplace researchers can benefit by emphasising practice as an analytical unit to understand workplace learning. Moving the focus to individuals’ participation in practices, highlights the need to examine individuals’ agency and propensity to participate (Gherardi, Citation2016; Hodges, Citation1998). Students engage in workplace practices and engage with a wide set of knowing (Duguid, Citation2005). Analyses of knowing do not only involve specific techniques engaged at a particular site, but also other developments in individuals’ sensibilities as they engage in and reflect on their practice (Hole, Velle, Riese, Raaheim, & Simonelli, Citation2018). In other words, we wish to emphasise the contributions of individuals as they engage in situated practices.

This analytical turn blends well with Billett’s (Citation2009a) advancement of personal epistemologies in workplace learning. Personal epistemologies are individuals’ perception of learning; how they engage with knowing and how this knowing develops as they participate in various working practices. Barton and Billett (Citation2017) conceptualise personal epistemologies as “In essence, they comprise what individuals know, can do and value which then directs how they think, act and learn” (p. 113).

Personal epistemologies are precipitated by practices in which they are continuously developed (Billett, Citation2009a; Strati, Citation2003). Hence, we approach personal epistemologies from a sociocultural perspective. A sociocultural approach to personal epistemologies emphasises the interplay between individual and contextual factors for individuals’ appraisals of knowing, and their own role in enacting knowing (Magolda, Abes, & Torres, Citation2008). We aim to capture this by emphasising a situated and emergent role of knowing, and how this can be framed by focusing on various expressions of knowing as accounted by the students.

The notion of two co-dependent, and equally valuable dimensions of knowing can be traced to Ryle (Citation2009, first published 1949). Ryle finds dimensions of knowing to be expressed as knowing that a thing is (conceptual knowing) and how this thing could be used by individuals (procedural knowing). Duguid (Citation2005) maintains that procedural and conceptual knowing are emergent expressions of behaviour, and not categories of knowledge that can be contained separately. Brown and Duguid (Citation2001) claim that “research often seems to evade this contrast rather than confront it” (p. 198). They suggest that practice-oriented theories provide a way to bridge the analytical continuum between forms of knowing and individuals’ personal epistemologies, which explains how individuals engage with knowledge in practices.

Knowing in the workplace is often analysed as tacit or procedural on the one hand, and articulated, standardised or conceptual on the other (Duguid, Citation2005; Eraut, Citation2000; Gascoigne & Thornton, Citation2014). These two dimensions are sometimes treated as given categories. We treat them as emergent expressions: knowing is developed, halted, and further nuanced over the course of individuals’ lives, and dependent on contexts (i.e. work) with which individuals engage (Duguid, Citation2005; Polanyi, Citation1962). Students’ engagement with practices in workplaces yields particular engagement with these expressions of knowing, in which students must enact complex practices and encounter knowing particular to the setting of their work placements (Billett, Citation2003; Lave, Citation1996).

Finally, accounts of students’ participation in work placement practices need to account for individuals’ volition to engage with these working practices, and whether individuals transform practices rather than conform to existing practices as a matter of course (Gherardi, Citation2009a). As outlined by several sociocultural theorists (e.g. Rogoff, Citation1995; Wertsch, Citation1998), individuals’ engagement with knowing in practices depends on social and historical underpinnings, which determine the individuals’ propensities to pursue actions and working knowledge, and which we conceptualise as individuals’ dispositions (Prawat, Citation1989).

Context

The included education programmes offer varying types of work placements to their students. The three settings are defined professions, with long-standing academic antecedents (i.e. scholarly work upon which curriculum is based) and were chosen to provide a multifaceted perspective of students’ engagement with workplace practices. Also, the work placements were selected since they are similar in form: the learning outcomes are pre-defined, and the students receive guidance by a host. Otherwise, the work placement is not systematically controlled.

Research of individual work placement settings incorporated in the present study are available for MPE (Brøske & Saetre, Citation2017) and TE (Ulvik, Helleve, & Smith, Citation2018). Brøske and Saetre (Citation2017) focus on the role of societal integration in MPE. Ulvik et al. (Citation2018) focus on the dichotomous perception of learning between working and campus settings in TE. No previous research on the AM focus group has been conducted. In the present study, we focus on iterations of knowing as personal epistemologies as they emerge in work placements in the various programmes.

Music Performance Education

MPE is organised as a four-year bachelor programme and an optional two-year master programme at the Norwegian Academy of Music, an artistic and academic university college in Oslo, Norway. The master programme offers a range of work placements, of which two are included here. One is a week-long multi-activity project carried out collaboratively by students and teachers and a range of partners in a Norwegian municipality. The project entails planning and giving concerts for new audiences in a variety of venues and is based on a high degree of collaboration with local musicians, children, and teachers. The second work placement, the professional orchestra placement programme, is an elective master course for which students apply based on an audition. Over a period of two years, students participate as orchestra musicians in professional orchestras during twelve week-long rehearsal and concert projects. Each student is appointed a supervisor from the orchestra, which normally is one of the orchestra musicians. While MPE offers a work placement in an orchestra and in a municipality collaboration, their emphasis is towards a performance and collaboration with the public, which contrasts to the focus of the traditional education.

Aqua Medicine

The profession programme in AM is a five-year integrated master programme at the University of Bergen, Norway. The curriculum of the AM programme is similar to the curriculum of a disciplinary biology programme, but with an emphasis on aqua medicine. The programme provides training in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of illness and injuries in aquatic organisms, and especially on farmed fish. Upon completion of the programme, the students can apply for the title of Aqua Medicine Biologist. An Aqua Medicine Biologist has prescription rights to treat and handle aquatic organisms. The programme includes two work placement periods of 15 and 12 days, primarily in fish farms. During the first placement, the students work in an aquaculture farm in order to familiarise themselves with aqua culture work. During the second placement, they work as Aqua Medicine Biologists, with emphasis on fish health diagnostics. The AM work placements focuses on the complexities of assessment of fish health and the myriad of stakeholders that AM biologists engage with during their work. The work placements are assessed by attendance and one graded written report.

Teacher education

TE is represented by three university-based secondary school teacher education programmes at the University of Bergen, Norway. The educations include a five-year integrated programme that leads to a master’s degree and two one-year postgraduate programmes for academic and vocational teaching. There are some variations among the programmes, and they all include two seven- to eight weeks’ periods of work placement. In the placements, TE focuses on the enaction and planning of teaching, classroom leadership and interaction with students. The teacher students most often have two supervisors selected by the school. Norwegian teacher education is regulated through a national framework. In work placements, there are no demands related to content or mentoring, except a fixed duration, and with a pass or no pass assessment. Work placements are mandatory components of TE, and the students do not receive academic credit points for this part of the programme.

Methods

We wish to highlight emergent themes that explain students’ experiences of their own learning across and between educational programmes. By making visible the accounts that emerges from these programmes, we invariably must analyse our findings through a broad lens. The students’ appraisals of knowing, practices, and learning were captured through focus group discussions. Brinkmann (Citation2007) has advanced that interviews can increase focus on epistemic content to garner more information about learning from participants. Thus, asking students to narrate an activity is not necessarily sufficient to grasp the information they have to offer. Rather, the discussions enable students to discern knowing as it relates to their experiences. By facilitating the opportunity for student groups to narrate their personal epistemologies, they situate themselves in their work and how it affects their knowing. It also affords the participants a chance to contrast their own experiences with other students. Focus groups were selected because the students share a collective set of experiences which they can discuss in relation to each other. As pointed out by Wilkinson (Citation2016), it is possible to draw findings from the way in which students present themselves to each other. For instance, one student might contrast their work placement learning with campus-based learning. Other students might find merit in these sentiments, but also feel the need to highlight the ways in which their learning at campus prepared them for their work placements, thus providing increased nuance to their accounts of their learning. This approach also carries the potential weakness that vocal participants in the discussion can lead other participants, this requires some probing by discussion leaders to somewhat mitigate.

Following recommendations given by Barbour and Kitzinger (Citation1999), the group discussions were centred on core themes with supporting questions aimed to foster students’ independent discussions. The focal discussion themes were common for all three education programmes and were constructed through meetings between the authors. The themes were constructed to ensure discussions about personal epistemologies, and the students’ engagement with workplace practices. Three principal discussion themes were selected: (i) the characteristics of learning at a workplace, as opposed to a campus setting; (ii) a characterisation of activity during the work placements; and (iii) learning outcomes in the work placements in general terms (i.e. the students gave accounts of concrete learning experiences and how they manifested). By highlighting these different aspects of learning we aimed to gather accounts of the students’ appraisal of their own learning and thereby address the research question. The students were informed of our aim to understand their conceptions of learning in conjunction with their work placement experiences.

The themes were divided into sub-questions. Probing questions were asked to clarify and further pursue themes that were raised by the students (e.g. “Tell me more about holding fish, how do you do that?”). To ensure that the correct meaning was captured, the students’ utterances were repeated for validation (e.g. “So you think learning in the workplace is different because you encounter weather?”; “Just to make sure that we have the correct meaning, you think that learning in workplaces are different from learning at campus?”).

No personal data was stored and after a review by Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) no formal application for data storage was required.

Selection and procedure

The participants consisted of nine Music Performance students (one orchestra interview and one multi-activity project interview), six fish health students (one interview) and 21 teacher students (one integrated teacher education-, and two post graduate student interviews) for a total of six focus groups. The participants were recruited through self-selection by approaching students in each study programme and inviting participants who had completed their work placements. The students were asked to collaborate in a project about learning in work placements. The students were informed that the discussions would be anonymised at the outset. The discussions consisted of one moderator in each group (three moderators) in the Teacher Education programme and two moderators in Music Performance and Aqua Medicine programmes interviews. When two moderators were present, one had the principal role of facilitating the discussion, while the second moderator observed and ensured that all items of the discussion themes were covered. Each interview took approximately one hour and was transcribed verbatim for analysis. In cases where individual moderators conducted interviews, the disciplinary group performed the initial analysis in concert, before disseminating the results to the larger cross-disciplinary group.

Analysis

The students’ discussions were initially disseminated through presentations among the authors to discern the students’ accounts of their learning. We then employed a variant of constant comparison analysis, in which themes relevant across all interviews were selected iteratively. This method is recommended for focus group research that focuses on specific themes and the shared experience among several participants (Onwuegbuzie, Dickinson, Leech, & Zoran, Citation2009). The relevant themes emerged as we selected the following instances of expressions of knowing: (i) knowing that is developed in-situ, and sequential sets of knowing, which is procedural, (ii) knowing that is propositional or conceptual, and concerned with overarching principles, and (iii) students’ dispositions (e.g. values and subjectivity) as students relate them to work placements.

These three instances are inspired by Billett’s (Citation2001) outline of workplace learning. For example, the students’ accounts of a particular situation could express procedural knowing through students’ account of their enactment of a particular task, and dispositions when students discuss their motivations to engage in the particular task.

The strength of this analytical approach is the emphasis and legitimisation of diverse expressions of knowing, and how these expressions are continuously enacted through work and individuals’ life histories. The approach also attends to criticism of sociocultural and cognitive theory to overly focus on either individuals or the social context in which individuals act (Hodkinson, Biesta, & James, Citation2008). By examining individuals’ accounts of knowing as they come to engage in workplace practices, we aim to capture the intersection between individuals’ thinking and their development in particular contexts (i.e. work placements). The instances were selected using NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 12.1.2.256), and the instances were then reviewed and discussed among the authors to ensure that they represent the findings.

Findings

Our analysis revealed three prominent themes in the students’ epistemological accounts: (i) professional judgment; (ii), professional practice; and (iii) professional identity. All three derive from individuals’ engagement (or willingness to engage) with workplace experiences. These themes are related to personal epistemologies as they explain students’ perspectives on their learning process in work placements. The themes are presented and further discussed below. All excerpts are our translation from Norwegian to English.

Professional judgment

Being afforded access to tasks with a real chance of failure has long been held to be a prominent feature of work placements, and is often portrayed as a stark contrast to campus-based activities that may seem contrived (e.g. Costley, Citation2011; Grossman et al., Citation2009). The students in all three programmes mirror this sentiment. However, it is offered here not merely as an experience, but as an experience that inform students’ personal epistemologies and in turn their judgment towards future work. Thus, being afforded the potential to fail seemed to accord the students with a sense of the value of failure for their own learning, and a sense of actions needed to mitigate and handle difficult situations appropriately in the future. Also, when failing has momentous consequences, the students adopt a sense of responsibility that can have a positive influence on learning.

Musicians striking the right (and sometimes wrong) note

The multi-activity project was perceived by the Music Performance students as a project consisting of several varied activities, in which they are given a great deal of freedom and responsibility. They were involved in many artistic productions within a short period and aimed at the same time at high artistic quality. The students perceive this particular combination as highly relevant to their development as musicians, because they believe this is how performances for an audience works.

I have gathered that the concert is about the music and playing together. Especially the times you play with the locals, and they were really happy that we were there. [It’s about] making a good show. And it wasn’t about [me], but about the band’s performance for the audience. The entire scene is connected. You forget that it is theatre, it is sound, lights. Everything is supposed to work to make a good show. If I play the wrong notes I can’t go around being disgruntled.

As illustrated in the excerpt, participating in a variety of unfamiliar practices in the multi-activity project, such as teaching, collaborating with children, and amateurs or improvising, is experienced as a high-risk endeavour. The multi-activity project constitutes a distinct practice context in that it includes the complex and high-risk features of professional practice. Yet, it is embedded in an educational setting, as students have lower expectations than employed musicians.

Alone in the fjords

The Aqua Medicine students seem to have encountered specific challenges pertaining to their location in Norwegian fjords as a sole professional far away from the University and fellow professionals. The students also gave accounts that indicated a novel enactment of procedures related to diagnosis of fish diseases and injuries. For instance, some symptoms might not be as clear in the field as it was during lectures or demonstrations at campus.

Much of what is presented during teaching sessions is the ideal portrait. A professor can present on a blackboard and, in a way optimize all factors. It is something completely different when you’re standing out there and it is blowing 22 m/s and it is snowing sideways.

Engagement with work placement complexities expanded the students’ conceptions about sickness and symptoms. Further, as these experiences pertained to enterprises’ success, the activities became more important. One student explained these issues in the following way:

[They] are responsible if it goes to hell, it was twenty against one. So, you need to have some balls too, you have to be able to put people in their place, for this is a company that is contracted to perform a specific job. They are assessed on how much time they use. On a treatment for example. Because time is money.

Here, the student emphasised the monetary pressures in enacting Aqua Medicine, a pressure that is perceived to increase by the prospect of making decisions alone and quickly.

Teacher students and authority

It was great to just be able to be alone in the classroom. To try to do exactly what I wanted, I had the authority. The other authority [supervisor] wasn’t in the classroom. I was responsible for everything, everything I put forward.

As the above quote suggests, the teacher students emphasised the importance of being autonomously responsible for a class. In being left alone with no external supervision, students were afforded a sense of freedom to conduct themselves as they saw fit. Other students interjected with the apprehension they experienced at the prospect of exercising authority to discipline students, or otherwise behaving as a teacher.

I got to experience situations where I got some exercise in talking with people in the hallway. And that was things I was very nervous about, taking the step to point at a guy: “YOU are coming out into the hallway”, or something like that. I thought that was really great, at least that I was allowed to test out such things.

The situation above indicates that the student found coming to grips with confrontational situations valuable. “Talking in the hallway” refers to removing the students from regular lectures to discuss their behaviour. Being nervous about implementing the steps also underscores the level of risk the student perceived in the situation. That is, the potential of failing to exercise authority in the classroom.

Professional practice

Professional practice can encompass the procedures by which work is enacted. However, professional practice refer to tasks that are encountered by students, and can take procedural, conceptual and dispositional dimensions. Routines can be continuously repeated every day or only intermittently. Ryle (Citation2009) emphasised how the enactment of procedures (knowing how), such as routines, emerges in concert with conceptual knowing (knowing what). Thus, procedures are analytical, and routines can encompass various elements of knowing as they are enacted by students. As the students have taken part in practices in work they have come to develop and appreciate knowing (i.e. their personal epistemology) related to various practices (Hole et al., Citation2018). Additionally, the students detail in length the relationship between these routines to their conceptualisations of learning. This is particularly true when students engage in routines in the context of supervision and discussions regarding their own knowing (Gherardi, Citation2009b).

Performing music

I would like to learn more about how to act in an orchestra or how I better can attach myself to other instruments. And when am I supposed to listen to the second oboe? And how in the world am I supposed to listen to the second oboe, which sits all the way over there? There is no focus on that in a school orchestra.

As illustrated in the above excerpt, rehearsing and performing a repertoire in a professional orchestra setting constitutes the core procedural knowing the students encounter in the orchestra placement programme. The students describe how they learn ways of listening, ways of watching, and of acting in the orchestra. In the orchestra, the students receive less direct feedback from supervisors, and is according to the students more a matter of learning by doing by having to “pick up things” according to the students. This entails identifying and listening to specific instruments in order to play on time, learning to count, experiencing the need for clear musical communication, and “how to be in the orchestra”. These ways of learning are a result of students engaging with practices, and as being enculturated in a specific professional orchestra circumstance. The orchestra offers the students a range of tools to understand orchestra playing and acting. According to the students, a main difference between the professional- and school orchestras is the higher musical level of the former. This level demands serious and focused practicing of the orchestra repertoire.

Measuring fish

The Aqua Medicine profession students described their engagement with procedural knowing initially to consist of fish-handling skills. This was particularly salient when working with fish farmers, as opposed to their work with fully trained Aqua Medicine professionals. Their engagement included being able to hold the fish, where the hands needed careful placement to prevent the fish from slipping. As one student iterated:

Coming out on a facility as an Aqua Medicine Biologist, and never having handled trout, then you make a fool out of yourself.

The students also worked on the routine maintenance of the fish farm. This routine was performed in cooperation with an aquaculture farmer and consisted of weighing, cleaning, and transferring fish. These routine tasks consisted of different procedures from the ones the students had engaged with prior to their work placement. The students also described fish farmers’ extensive knowing when observing fish movements in the fish pen and other tacit knowing, which enabled them to detect diseases and injuries quicker than the students. The students emphasised how these routine tasks were equally important to master as the more specialised knowing used by Aqua Medicine Biologists.

Enacting and maintaining lessons

The teacher students are learning a profession that they have observed for years in the classroom. They have several conceptions concerning what teachers do in a classroom. However, the teacher students describe that while they as pupils witnessed what took place at “the stage”, they were as teacher students allowed backstage and became aware of teachers’ responsibilities outside the classroom. They furthermore encountered a bodily and emotional experience of teaching and understood how complex and time consuming it can be.

I was really surprised over how much time we used. Both for preparations, to conduct the lessons, but not least on conversations after lessons, which, in a way, I benefited most from.

The teacher students also discussed the varying degrees of participation offered to them by the schools they attended during the work placement. They appreciated having supervisors that gave them some advice, and who also encouraged them to try out their own ideas. Moreover, they enjoyed being included in the staff and engage in knowing embedded in the professional community in an informal way. The teacher students’ access to procedural knowing varied. Some were left to their own trial and error. Others were invited into a dialogue or told more specifically what to do.

Professional identity

Dispositions have come to take a more prominent role in understanding workplace settings and learning (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004). This is also reflected in the students’ accounts of their learning in workplace settings. Rogoff’s (Citation1995) emphasis of participatory appropriation, meaning individuals’ willingness to change to accommodate new routines and willingness to engage with the work presented to them, further describes the importance of dispositions to workplace learning. Identity permeates all the students’ accounts, both in terms of their backgrounds when engaging with new settings (i.e. practices), or willingness to solve challenges and use effort in their work (Billett, Citation2004).

Integrating audiences in performances

In the multi-activity project and in the professional orchestra placement programme, the students enacted conceptual knowing by stimulating discursive understanding of Music Performance in professional settings. Both groups believed that this is not taken sufficiently care of in campus settings. Both groups also find supervision and feedback (from teachers, peers, or experienced musicians) the most important factor stimulating learning in work placements. The high degree of collaboration and reflection in the multi-activity project is a central part of the students’ positive experience. Central learning experiences, such as the shift of focus from individual students to the music, audience, and other issues, seem to emanate from to the network of social relations at play in the multi-activity project.

I’ve been there a whole week, and everything was focused towards including, talking, trying to convey. So, I will take that with me into other projects. Not taking people on stage with me or take people with me home, but the focus from now on, after this project, will be directed towards those listening to me.

Thus, social practices seem to be central to students’ learning in the project, not least from their peers and from “new audiences”. The collaborative and reflective approaches seem to be a key factor in making these learning experiences explicit. The orchestra programme students also find supervision and feedback important, and they describe a context in which this happens both in less formal ways and less frequently. For instance, the students identify feedback from experienced fellow musicians (mainly individual feedback from the person “next to me”) as a highly valuable way of learning in orchestra practices. These statements give a hint of the strengths of the social mechanisms at play in these rather different social contexts of the multi-activity project and the professional orchestra.

The multi-activity project seems to have brought on a range of questions about the role and tasks of the students as future musicians, about music itself, of working as a portfolio musician, and of “expanding the frames”. Since the students start to question reasons for becoming a musician and what kind of musician they want to be, there is an epistemological shift in focus from simply gaining expertise in their respective instruments. In comparison, the orchestra students highlight the importance of having a chance to understand the orchestra practice of networking and of finding a “way into” the orchestra. In these learning experiences, the students are enculturated in a professional orchestra practice, with codes, procedures, musical, and bodily actions, and spoken statements and feedback.

Fish farming: a matter of geography

The Aqua Medicine students came to develop their sensibilities about how to approach their work as Aqua Medicine Biologists. First, in terms of the cultures the practices they encountered were perceived to derive from. Second, in terms of their individual subjectivity (i.e. values and assumptions) when they encountered work. One student described his engagement with the working practices in terms of backgrounds. According to this student, fish farming originates in Northern- and Western Norway, whereas as an Eastern Norwegian, he had no underpinning cultural framework to understanding the Aqua Medicine work. Another student iterated that “It is no secret that many of those who work as fish health professionals in Norway come from Northern- or Western Norway”.

The students also emphasised the relationship between their enactment of their knowing and their identity as Aqua Medicine Biologists. This was determined by the students’ emphasis on how they imagined the fish farm workers’ derision of Aqua Medicine Biologists who could not handle living fish:

How should they take me seriously if I cannot even handle the fish? Well, to be able to help them throw the net and to collect fish and feed the fish and do these sorts of things. Well, it is a bit stupid to just stand and look like some idiot, you have to contribute.

These are the students’ expressions of values they perceive in the Aqua Medicine profession, and as they have encountered them in their work placements. The students at some level negotiated how they would act in contentious situations. One student gave an account of a supervisor Aqua Medicine Biologist being confronted by several fish farmers who disagreed strongly against their pharmaceutical recommendations. The Aqua Medicine Biologist was confronted with farmers who could potentially lose large profits. This illustrates the effort sometimes required to act appropriately as an Aqua Medicine Biologist despite local pressures. It also intersects with interests of the local community (i.e. the workplace), professional standings of fish farmers in general, and students’ sensibilities about the role of values and willingness to actively maintain their own values.

Moving from student to teacher

The teacher students seemed to develop an initial understanding of themselves as teachers through the work placement. They emphasised that it was important to access the professional community and learn more about teachers’ overall responsibilities. Further, they engaged in a broader understanding of what it implies to be a teacher, such as the complexities of the work and the many roles that teachers simultaneously have to assume when encountering students, colleagues, or supervisors. Thus, teacher students in work placements seemed to consider the extent to which they are suited for teaching and what kind of teachers they want to become. The teacher students had different preferences related to freedom and responsibilities. Still, they shared the wish for some kind of autonomy to enact teaching practices and thereby evolve their understandings of themselves as teachers.

Teacher students have a preconception of teaching based on curriculum literature, lectures, and observations. In work placements, they develop an emotional- and experience-based conception of their role. Literature and scientific concepts also became more meaningful and they saw how it might contribute with a critical view of their own practices. Some teacher students iterated that their workplace experiences made them more interested in reading scholarly literature or made them to shed light upon previous experiences. When it comes to curriculum literature, the students indicated that their work placement experience was not aimed at connecting learning at campus with learning during work placements. Several students indicated that work placements and the university coursework emerged as two separate epistemologies. For instance, one student iterated that:

It was weird having a university teacher who said: “don’t just read the syllabus, there is so much more out there”. And then I had a school [workplace] supervisor who says: “stick to the curriculum, that’s what the students learn, and that’s what they use”.

The excerpt illustrates a conflicting view offered by university teachers and workplace teachers to the student. In this instance, the student did not reach a conclusion as to what view she preferred. However, the participation in teaching practices offered the student an insight into the thinking of teachers in the workplace and those found at campus.

Discussion

All students gave epistemological accounts concerning their engagement with knowing (i.e. procedures and conceptions) and dispositions in their work placements. They had previously encountered these dimensions in some form at campus and otherwise in their lives. Additionally, they engaged with practices not previously encountered at campus. These experiences constitute subjectivity in construing learning as it arises in workplace situations, and thus development of students’ personal epistemologies in work settings. sums up our findings and the various expressions related to the three prevalent themes in the students’ accounts.

Table 1. Enacting personal epistemologies in work placement practices.

Music Performance students have engaged with musicianship procedures for several years when playing instruments. During their workplace experiences, however, students were afforded engagements with concert performances that had an influence on the local community. The planning had to consider several contextual factors. The performance itself became less prominent in the face of the integration of performances with the local community. This corresponds to the fish health profession students who have advanced their laboratory capabilities during their campus-based experiences. In work settings, this knowing was challenged because multiple confounding factors had to be accounted for (e.g. weather, limited time, and the opinion of the local farmers). The teacher students experienced similar developments where some found that keeping their pupils focused was less important than anticipated. Instead, their principal challenges were unanticipated instances, such as hallway encounters or one-to-one counselling.

Expressions of knowing and working experiences

Through their workplace experiences students considered expressions of dispositions, and conceptual and procedural knowing (Billett, Citation2001; Magolda et al., Citation2008) across all participants and programmes. However, the findings reveal that there was increased emphasis on particular expressions in different programmes. The Aqua Medicine students gave accounts of a dichotomy between their schooling at campus, which provides extensive conceptual knowing, and procedural knowing provided in their work placements. This was evident in accounts such as how the students found they could not really count the lice on fish. According to one student, counting lice was something they had learned at campus, but was unable to complete in the work placement. In contrast, the Music Performance students revealed that aspects of their procedural knowing were extensively engaged through their overall experience as musicians, and at campus. They engaged with other domains of knowing in their work placements, namely how communities and musicians interact in the enactment of concerts and other performances. Thus, the understanding of concepts was developed for Aqua Medicine and Music Performance students, where lice counting and performance encapsulated aspects they had not considered prior to the work placement.

This dichotomy between affordances of knowing at campus and through work was highly problematic among some Aqua Medicine students. The enactment of their occupation was seen to more legitimately take place in work placements than at campus. This tension between occupational- and campus training has been documented in several education programmes, such as in teacher education (e.g. Korthagen, Citation2010). Across all participants and work placements, the tension emerged as: (i) conflicting recommendations for literature as experienced by teacher students, (ii) as complexities in sampling and laboratory work among Aqua Medicine students, and (iii) as ways to follow fellow musicians in participating in an orchestra, or the enactment of a successful performance with a variety of communities to attend to among the Music Performance students. In these cases, students seemed to convey that they had been misled on campus at some point or provided an inaccurate representation of their working life.

Aqua Medicine Education is aimed towards a specific occupation, as opposed to other biology students, with whom they share a substantial amount of coursework. It is therefore interesting to note that a perception of misleading content at campus exists in the Aqua Medicine programme. The shared coursework raises questions as to the extent to which this tension is promoted by work placements or is also prevalent in disciplinary educations. Given this, it is important to emphasise that the students’ expositions still indicate that their engagement with complexities through work further developed their critical sense as to what constitutes valuable learning at campus. That is, to what degree it is valuable to implement concepts, procedures and values as disseminated by teachers in their understanding of their work as Aqua Medicine Biologists.

According to the students’ utterances from all three programmes, we suggest that the students have developed their independent understanding of their education. They better understand how to enact their knowledge and what knowledge to pursue further. In other words, we have documented instances of procedural and conceptual learning, which is superseded by the students’ accounts of their subjectivity in engagements with practices. These findings align with diverse approaches to learning in higher education (Billett, Citation2009b; Eraut, Citation2004). Baillie, Bowden, and Meyer (Citation2013) criticise the strong emphasis on singular iterations of knowledge (i.e. procedures and concepts) in higher education, and call for a new focus on individuals’ dispositions to act at a later stage. That is, what procedures and concepts the students will pursue, and the extent to which they will put effort into their learning. Indeed, several authors have found that dispositions have a close relationship with learning (Hodkinson et al., Citation2008; Prawat, Citation1989). In our study, this is also illustrated by the teacher students’ emphasis on being provided with an appropriate level of freedom to experience risk and to autonomously plan and execute lessons.

Conceptual model

We have employed a wide conceptualisation of students’ engagement with work placement epistemologies by including concepts, procedures, and dispositions. The purpose of this wide approach was to make use of developments in practice-oriented research that conceives of learning through practice by analysing knowing in expressions such as procedural and conceptual knowledge, and dispositions (Billett, Citation2001; Duguid, Citation2005) and to capture their relevance to investigate three different work placement schemes.

An important finding concerns the differentiating dimensions of conceptual and procedural knowing enacted by the students. A second finding concerns students’ dispositions, which is based on an emphasis on students’ volition to engage with the knowing that develops in working practices. This volition is based on individuals’ dispositions as they are formed through individuals’ life histories, and further developed as students engage with work in the context of their studies.

The workplace practices were enacted in communities, such as those encountered by setting up a show in a small town (Music Performance students), in the rural culture of Western Norway (Aqua Medicine students), and the school community (Teacher Education students). Conceptually, the communities initiate practices that accommodate students’ learning through their engagement, and shape students’ propensities to further engage. These engagements then shape students’ trajectories through personal epistemologies related to their present and future work.

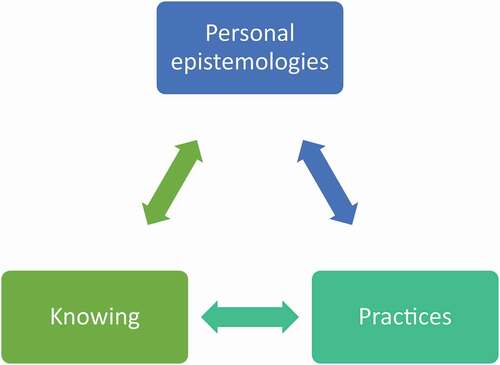

Magolda et al. (Citation2008) hold that students’ encounters with diverging knowledge claims, including those underpinned by various social settings (e.g. campuses and workplaces), are crucial for the development of subjectivity in their knowledge claims. Thus, the extent to which procedures, concepts and dispositions are developed can hardly be separated from their personal epistemologies. Our findings support the notion that crucial learning within work placements is not necessarily connected to the access students are given to specific iterations of knowing. Instead, the learning is connected to the development of personal epistemologies that are born from encounters within the work placement. We propose the following model () to conceptualise the relationships between workplace practices, the knowing found in enacting these practices, and personal epistemologies engendered by engaging and discussing knowing.

The three instances proposed in (practices, knowing, and personal epistemologies) should not be construed to be causal. Rather, all three instances coexist and develop concurrently as individuals engage in working practices. As argued by Rogoff (Citation1995) and other sociocultural learning researchers, discerning learning as continuous implies concurrent rather than intermittent learning.

Conclusion

By documenting how knowing and dispositions intermingle in the students’ accounts of personal epistemologies, we have aimed to provide a new lens through which educators and researchers can understand learning through work placements. In pedagogical terms, the inclusion of dispositions can be a valuable asset to traditional focus on conceptual knowing in relation to students’ education. Based on our findings, we argue the core activity of a work placement as the following:

To perform or take part in authentic work that is relevant for the education and future occupation of the student.

To perform or take part in authentic work differs from other teaching activities in that the tasks are not executed for the sake of training. This implies that the student has some level of responsibility for a product or result that is used outside the educational setting.

A work placement should be performed in a working community and with one or more mentors.

Reflection on personal epistemologies, e.g. on the connection between practice and knowing, will help to optimise students’ learning.

Further study is required to gauge the extent to which students’ perception of highly crucial learning occurs solely in work placements, which should indicate change in teachers’ approaches to students’ learning in campus. Nevertheless, simply acknowledging the complexities of practice in regular teaching can aid students to adjust expectations and enactment of their knowing in work placements.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sondre Lode and Kari Smith for their aid in data gathering and interpretation. Thanks to all student participants for sharing their thoughts. This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council under Grant 238043; Programme for Evaluation and Quality Development at the University of Bergen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Torstein Nielsen Hole

Torstein Nielsen Hole (PhD) is an advisor at the Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education where he works with the Centres for Excellence in Education scheme. He has worked as a researcher and associate professor in education and his research interests include active learning, epistemology, and workplace learning in higher education.

Gaute Velle

Gaute Velle (dr.scient) is a researcher at NORCE and professor in biology at the University of Bergen. Apart from his research interests in biology he is interested in active learning and work placements.

Ingrid Helleve

Ingrid Helleve (PhD) is a professor in education at the University of Bergen. Her research interests include professional development, digitization and teacher education.

Marit Ulvik

Marit Ulvik (PhD) is a professor in education at the University of Bergen. Her research interests include professional development and teacher education.

Jon Helge Sætre

Jon Helge Sætre (PhD) is an associate professor and leader of the Centre for Excellence in Music Performance Education at the Norwegian Academy of Music. His research interests include music in schools, teacher education and specialist music education.

Brit Ågot Brøske

Brit Ågot Brøske is an associate professor at the Norwegian Academy of Music. Her research interests include intercultural collaboration in music education and music teacher training.

Arild Raaheim

Arild Raaheim (PhD) is a professor of higher education at the University of Bergen. His research interests include digitalization, learning and assessment in higher education.

References

- Baillie, C., Bowden, J. A., & Meyer, J. H. F. (2013). Threshold capabilities: Threshold concepts and knowledge capability linked through variation theory. Higher Education, 65(2), 227–246.

- Barbour, R., & Kitzinger, J. (1999). Developing focus group research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208857

- Barton, G., & Billett, S. (2017). Personal epistemologies and disciplinarity in the workplace: Implications for international students in higher education. In Professional learning in the work place for international students (pp. 111–126). Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60058-1_7

- Billett, S. (2001). Learning in the workplace: Strategies for effective practice. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Billett, S. (2003). Sociogeneses, activity and ontogeny. Culture & Psychology, 9(2), 133–169.

- Billett, S. (2004). Learning through work: Workplace participatory practices. In H. Rainbird, A. Fuller, & A. Munro (Eds.), Workplace learning in context (pp. 109–125). London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203571644

- Billett, S. (2009a). Personal epistemologies, work and learning. Educational Research Review, 4(3), 210–219.

- Billett, S. (2009b). Realising the educational worth of integrating work experiences in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 34(7), 827–843.

- Billett, S. (2014). Integrating learning experiences across tertiary education and practice settings: A socio-personal account. Educational Research Review, 12, 1–13.

- Billett, S. (Ed.). (2015). Integrating practice-based experiences into higher education. In Integrating practice-based experiences into higher education (pp. 1–26). Dodrecht: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Billett, S. (2017). Developing Domains of Occupational Competence: Workplaces and Learner Agency. In M. Mulder (Ed.), Competence-based Vocational and Professional Education (pp. 47–66). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_2

- Brinkmann, S. (2007). Could interviews be epistemic? An alternative to qualitative opinion polling. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(8), 1116–1138.

- Brøske, B. Å., & Saetre, J. H. (2017). Becoming a musician in practice: A case study. Music & Practice, 3, 1–21.

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40–57.

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2001). Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213.

- Costley, C. (2011). Workplace learning and higher education. In M. Malloch, L. Cairns, K. Evans, & B. N. O’Connor (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of workplace learning (pp. 395–406). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200940.n29

- Crebert, G., Bates, M., Bell, B., Patrick, C. J., & Cragnolini, V. (2004). Developing generic skills at university, during work placement and in employment: Graduates’ perceptions. Higher Education Research and Development, 23(2), 147–165.

- Duguid, P. (2005). “The art of knowing”: Social and tacit dimensions of knowledge and the limits of the community of practice. The Information Society, 21(2), 109–118.

- Eraut, M. (2000). Non‐formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 113–136.

- Eraut, M. (2004). Transfer of knowledge between education and workplace settings. Workplace Learning in Context, (2004), 201–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203571644

- Gascoigne, N., & Thornton, T. (2014). Tacit knowledge. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-8361.12123

- Gherardi, S. (2009a). Community of practice or practices of a community? In S. J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education, and development (pp. 514–530). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021038.n27

- Gherardi, S. (2009b). Introduction: The critical power of the ‘practice lens’. Management Learning, 40(2), 115–128.

- Gherardi, S. (2016). To start practice theorizing anew: The contribution of the concepts of agencement and formativeness. Organization, 23(5), 680–698.

- Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. W. (2009). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2055–2100.

- Helyer, R. (2011). Aligning higher education with the world of work. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 1(2), 95–105.

- Hodges, D. C. (1998). Participation as dis-identification with/in a community of practice. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 5(4), 272–290.

- Hodkinson, P., Biesta, G., & James, D. (2008). Understanding learning culturally: Overcoming the dualism between social and individual views of learning. Vocations and Learning, 1(1), 27–47.

- Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2004). The significance of individuals’ dispositions in workplace learning: A case study of two teachers. Journal of Education and Work, 17(2), 167–182.

- Hole, T. N., Velle, G., Riese, H., Raaheim, A., & Simonelli, A. L. L. (2018). Biology students at work: Using blogs to investigate personal epistemologies. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1–16.

- Kennedy, M., Billett, S., Gherardi, S., Grealish, L., Harteis, C., & Gruber, H. (2015). Practice-based learning in higher education: Jostling cultures. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9502-9

- Korthagen, F. A. J. (2010). How teacher education can make a difference. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(4), 407–423.

- Lave, J. (1996). The practice of learning. In S. Chaiklin & J. Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice - perspectives on activity and context (pp. 3–32). Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Magolda, M. B., Abes, E., & Torres, V. (2008). Epistemological, intrapersonal, and interpersonal development in the college years and young adulthood. In M. C. Smith & N. DeFrates-Densch (Eds.), Handbook of research on adult learning and development (pp. 184–219). Abingdon: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203887882.ch7

- OECD. (2017). Education at a Glance 2017. Author. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21.

- Parker, L. E., & Morris, S. R. (2016). A survey of practical experiences & co-curricular activities to support undergraduate biology education. The American Biology Teacher, 78(9), 719–724.

- Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Prawat, R. S. (1989). Promoting access to knowledge, strategy, and disposition in students: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 59(1), 1.

- Rogoff, B. (1995). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In J. V. Wertsch, P. Del Río, & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural studies of mind (pp. 139–164). Los Angeles: Cambridge University Press.

- Ryle, G. (2009). The concept of mind. London: Routledge.

- Strati, A. (2003). Knowing in practice: Aesthetic understanding and tacit knowledge. In D. Nicolini, S. Gherardi, & D. Yanow (Eds.), Knowing in organizations. A practice-based approach (pp. 53–75). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

- Trede, F., & McEwen, C. (2015). Early workplace learning experiences: What are the pedagogical possibilities beyond retention and employability? Higher Education, 69(1), 19–32.

- Ulvik, M., Helleve, I., & Smith, K. (2018). What and how student teachers learn during their practicum as a foundation for further professional development. Professional Development in Education, 44(5), 638–649.

- Wertsch, J. V. (1998). Mind as action. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wilkinson, S. (2016). Analysing focus group data. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 83–98). London: Sage.