Abstract

Background: Autologous fat transplantation (AFT) is being increasingly used to improve the results after breast-conserving surgery and breast reconstruction. However, studies on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after AFT are scarce. The aim of this prospective longitudinal case-series study was to assess PRO in women who had undergone AFT after surgery for breast cancer or risk-reducing mastectomy.

Methods: Fifty women, who had undergone breast-conserving surgery or breast reconstruction, needing corrective surgery, were consecutively included between 2008 and 2013. A 20-item study-specific questionnaire (SSQ) and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) were used pre-operatively and 6 months, 1 year and 2 years post-operatively, to evaluate PRO and HRQoL.

Results: The patients underwent three (1–4) AFT procedures, with the injection of 164 ml (median) (range 40–516) fat. Thirty-eight and 34 patients completed the study-specific questionnaire and the SF-36, respectively, both pre-operatively and after 2 years. Sixteen of the 20 items in the SSQ were improved after 2 years, including breast size (p < 0.0001), shape (p < 0.0001), appearance (p < 0.0001), softness of the breast (p = 0.001), pain in the region (p = 0.005), scarring from previous breast surgery (p < 0.001) and willingness to participate in public physical activities (p < 0.001). HRQoL did not largely differ before and after AFT, or between the study group and a reference population.

Conclusions: AFT alone or in combination with other corrective surgical procedures, improved PRO after breast-conserving surgery and breast reconstruction in both irradiated and non-irradiated women.

Introduction

Breast reconstruction in connection with, or after, breast cancer surgery is well known to improve quality of life [Citation1–3]. The surgical methods employed range from an oncoplastic approach in breast cancer surgery to extensive free-flap reconstructions. All have in common the possible need for surgical correction due to complications or less favourable aesthetic outcome. Patients who have received radiotherapy of the breast or the chest wall have a higher frequency of complications and reoperation [Citation4]. Common indications for reoperation due to unfavourable aesthetic results are indurations, scar contractures, tissue deficit and breast asymmetry. Autologous fat transplantation (AFT) has become a well-established technique for improving these conditions [Citation5]. Clinical results and surgeon’s opinions about the outcome after AFT are generally reported as good [Citation6–9]. The results of some studies indicate that surgeon-reported outcome and patient-reported outcome may diverge after breast reconstruction [Citation10–13]. The results of these evaluations can be valuable for patients facing quality-of-life-improving surgery in their decision-making process. There is also an increasing interest in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for the evaluation of the efficacy of health care [Citation14–16].

In most studies on patients’ opinions of the outcome of reconstructive surgery, only a single question has been asked [Citation8,Citation9,Citation17]. We have previously reported patients’ satisfaction after AFT in a questionnaire-based, descriptive cross-sectional study [Citation18]. The aim of the present study was to assess patient-reported outcome after AFT, prospectively and longitudinally, as part of reconstructive breast surgery. We also wanted to assess the patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) before and after surgery and learn if it is consistent with HRQoL of a Swedish reference population.

Materials and methods

Patients and design

The study design is a prospective case series including patients treated with AFT as part of corrective surgery at the Department of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden. The patients were consecutively enrolled from October 2008 until June 2013. All procedures were performed under the national health service. Those included were women who had undergone breast-conserving surgery with less favourable aesthetic results, and women who had undergone mastectomy and subsequent breast reconstruction, needing corrective surgery. The inclusion criteria were time after previous breast surgery or radiotherapy longer than 1 year and mammography and ultrasound examinations performed a maximum of 3 months prior to AFT, to exclude any local recurrences. Exclusion criteria were known breast cancer recurrence, contraindications for anaesthesia or surgery due to comorbidities, other serious systemic diseases that may affect the outcome of the procedure and inability to understand verbal and written information about the study. The patients’ characteristics are given in . The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm (2008/484–31/2).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Autologous fat transplantation

Fat aspiration was performed with a dry technique using a Coleman cannula and a 10-ml syringe at the donor site [Citation19]. Donor sites were the abdomen, knees, thighs, hips, flank area, in one case arms, and in another the case sub-axillary region. The fat was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min. Liquid fat and blood were poured off, and the remaining lipocytes were injected into the subcutaneous tissues at the recipient site in multiple layers and directions using a blunt cannula, 1.29 mm in diameter. Patients with implants received one dose of prophylactic antibiotics (cloxacillin provided they were not allergic, otherwise clindamycin). The patients underwent a median of three (1–4) AFT procedures unilaterally or bilaterally until satisfactory results were obtained. Other corrective procedures were performed concurrently in eleven patients: seven scheduled nipple reconstructions, one mastopexy, two scar corrections and one capsolutomy with implant change, abdominal advancement and liposuction of the axilla. The median time from the first AFT to last AFT was 12.3 months (range 4.2–27.5). All operations were performed under general anaesthesia and carried out by one of the authors.

Questionnaires and data collection

Demographic data were collected from electronic patient medical files that cover the whole catchment area. Hence, additional operations performed outside the unit and any complications treated at other hospitals would come to our knowledge. A study-specific questionnaire (SSQ) modified for this specific study population was used. The original questionnaire that SSQ was based on was developed by a psychologist [Citation20], who specialised in oncological patients, in collaboration with experienced plastic surgeons. It has been consequently modified for different studies focusing on other breast reconstructive methods and their outcome[Citation21,Citation22], This SSQ contains 16 items in which answers are given on a seven-point Likert scale (Q1–Q4 & Q9–Q20), and four items (Q5–Q8) where the responses are ‘Not at all’, ‘Little’, ‘Pretty much’ or ‘Much’. The BREAST-Q questionnaire was not available at the start of this study.

The Short Form Health Survey [Citation23] (SF-36) measures the patients’ long-term (4 weeks) HRQoL. It covers eight domains: physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning and mental health in 36 items. The mean scores for each domain were transformed into a value on a 0–100 scale, where a higher number represents higher functioning. The eight domains of the SF-36 were used to compare the patients’ HRQoL with that of a Swedish reference population, change over time within the group. The outcome of the reference population is provided in the Swedish translation of SF-36 and based on answers from 3260 randomly picked women aged 30–74 in seven Swedish regions during 1991–92.

The questionnaires were answered at baseline (before AFT) and 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after the final AFT, either by mail or at the outpatient clinic. Median follow-up (time from final AFT procedure to last completed questionnaire) was 24.2 months (range 11.8–32.3). The completed questionnaires were handled by the first author and not by the surgeon who performed the operations.

Statistical methods

The items on an interval scale in the SSQ (Q1–Q4 & Q9–Q20) were visualized using descriptive statistics and mean line graphs were plotted using the results from all SSQs from all patients (n = 48), to give an overview of the change over time for each question. The items were also analysed using a statistical model, Mixed-effect model repeated measures (MMRM), to assess the longitudinal data. This model incorporates the dependence of the measurements within a patient and allows missing data (i.e. SSQ not completed at 6 months and/or 1 year) to analyse only the answers from the patients who completed both the baseline and the 2-year SSQ (n = 38). The model generates an estimate of the mean change. The outcome variable was the change relative to the baseline, and the baseline value was included as a covariate in the model. Sensitivity analysis was performed for irradiated and non-irradiated patients. This was carried out to examine if AFT especially benefits the irradiated patients. It is not inconceivable since AFT is known to have a positive impact on irradiation-damaged tissue [Citation24]. Moreover, sensitivity analysis was performed for patients (92%) that had not undergone major additional surgery. The limit for the confidence interval was 95% for the difference between each time point and the baseline.

In the ordinal items (Q5–Q8), a quasi-symmetry model [Citation25] was used to estimate the chance of scoring one category more positive than one category more negative at follow-up. Since the responses were given on an ordinal scale, they cannot be treated as continuous variables in the analyses. The model acknowledges the ordinal scale and tests for an ordinal trend.

The level of significance was set to 5% (p ≤ 0.05) in all tests. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS® (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). No imputations were performed and no last observation carried forward was used.

No statistical calculations were performed for SF-36, since the number of patients only allow for detection of 10–20 point differences both over time within the group and between the patients and the reference population. Mean scores for the general Swedish population are given by sex and age categories in the Swedish translation of SF-36. The scores for women in the nine age categories between 30 and 74 years were used to calculate a mean score for all the women aged 30–74 (n = 3260). The means were weighted with respect of number of patients in each age category. In that way, the reference population and patients are matched on sex and age. Confidence interval for the computed mean for the reference population was not calculated.

Results

Patients

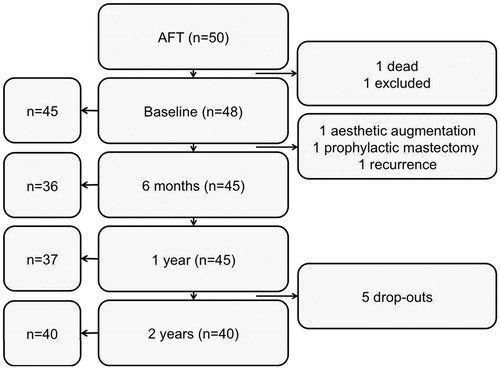

Fifty patients were recruited to the study. One patient died and one dropped out before completing any questionnaires. Among the remaining 48 patients, eight dropped out during the study period, but their completed questionnaires were analysed. One dropped out because of breast cancer recurrence, one underwent bilateral breast augmentation at a private clinic, one bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and five patients dropped out for other reasons (). Two other patients had breast cancer recurrence, but they did not drop out of the study.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patients’ participation in the study. Boxes on the left show the number of patients completing the study-specific questionnaire (SSQ) at each time point. Boxes in the middle show the number of patients participating in the study. Boxes on the right show the number of patients excluded and drop-outs.

Adverse events occurred in six patients: one patient had a wound rupture, one a haematoma at the donor site and four patients needed further investigations; three because of palpable lumps and one because of discomfort and swelling of the breast. Thirty-eight patients completed the SSQ and 34 patients completed the SF-36 both at baseline and after 2 years.

The total median volume of injected fat was 164 ml (40–516).

Study-specific questionnaire

Q1–Q4 and Q9–Q20

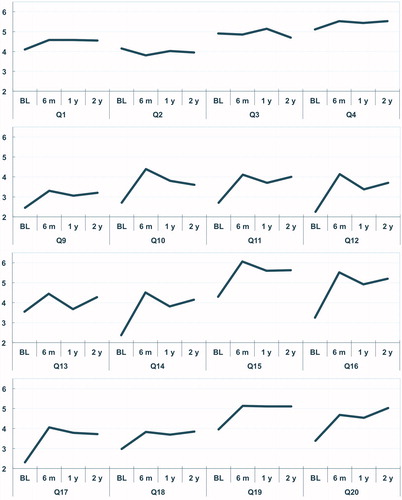

From the mean line graphs, it can be seen that the best results were obtained after 6 months, followed by a decrease after 1 year, and then an increase after 2 years (). Fourteen of these 16 items (Q1, Q4 and Q9–Q20) were improved after 2 years. The mean score and mean change between baseline and 2 years are given for each item in and .

Figure 2. Mean line plots for Q1–Q4 and Q9–Q20. The mean line plots for each item at each time point are shown for all patients who completed the SSQ.

Table 2. Results for Q1–Q4 and Q9–Q20 on sensitivity, pain, appearance, softness, trouble finding a good-fitting bra and willingness to participate in physical activities.

In the MMRM analysis, including only patients who completed both baseline and the 2-year questionnaire, thirteen of the 16 items were significantly improved after 2 years, for the entire group and in the sensitivity analyses for the irradiated patients and the patients who had not undergone additional surgery (Q4 and Q9–Q20). Q13 (softness of the breast) was not significantly improved after 1 year (). The non-significant items (Q1–Q3) concern the sensitivity of the breasts. The non-irradiated subgroup was too small to make any inferences from the data.

Table 3. Q1–Q4 and Q9–Q20.

Q5–Q8

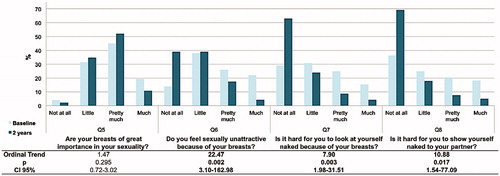

The ordinal trend, i.e., the probability of more positive scores after 2 years, was 22.47 (p = 0.002) in Q6 (sexually unattractive because of breasts), 7.9 (p = 0.003) in Q7 (seeing oneself naked) and 10.88 (p = 0.017) in Q8 (being naked in front of partner) (). The 95% CI was wide in all three items. The ordinal trend for Q5 (importance of breasts for sexuality) was not significant.

Figure 3. Q5–Q8 focusing on sexuality and willingness to be naked. The graphs show the percentage of answers in each category, for each item, at baseline and after 2 years. The ordinal trend is the chance of scoring one category more positive than one category more negative at follow-up. Significant items are given in boldface. CI: confidence interval.

SF-36

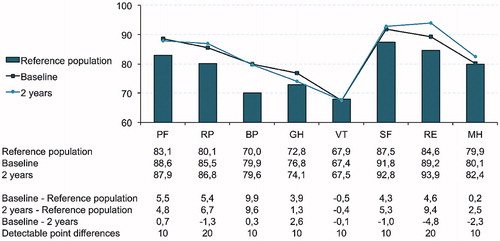

The mean scores for the eight domains for the reference population were compared with the mean score for the study group at both baseline and after 2 years. No point differences were large enough to be able to detect any significant differences in HRQoL between the study group and the reference population. Neither were there any large differences between the mean score at baseline and at the 2-year follow-up within the study group. The descriptive statistics are shown in .

Figure 4. Results for the eight domains of SF-36 of the study population and the age matched reference population of Swedish women (n = 3260). PF: physical functioning; RP: physical role functioning; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; VT: vitality; SF: social role functioning; RE: emotional role functioning; MH: mental health.

Discussion

Patient-reported outcome measures are important tools in evidence-based medicine [Citation26,Citation27]. The results are especially important when evaluating surgery intended to improve quality of life, rather than treating severe health conditions. A debate on oncological safety has been going on over the last three decades. It has been proposed that stem cells injected in a previous cancer site could induce recurrence [Citation28]. Consequently, women offered AFT as part of breast reconstruction or after breast-conserving surgery should be given evidence-based information about the outcome of the procedure before accepting further surgery. Information on the outcome of different procedures is also important for health-care providers and funding bodies. Despite the common use of AFT, few reports have been published on the change of patient-reported outcome over time and the quality of the reports is rather low [Citation26]. When this study started, the validated BREAST-Q form was not yet available, and could therefore not be used as recently recommended in the VOGUE study [Citation27]. Instead, a study-specific questionnaire was used to evaluate patient-reported outcome. The patients answered the questionnaire before AFT and at three-time points during the 2-year follow-up after completed AFT sessions. A research nurse handled the questionnaires. The aim was to assess possible changes in the patients’ opinion about the outcome over time. Resorption of the transplanted fat may lead to deterioration of the aesthetic result over time. On the other hand, as time passes, the patients may accept the cosmetic result to a larger extent and softening of the breast tissue [Citation29] could lead to patients expressing a more positive opinion over time.

In the present study, a more positive outcome was reported in 80% of the items 2 years after AFT than pre-operatively. The patients were more satisfied with the appearance of their breast with and without clothes, found the breast symmetry better, were more comfortable about being naked with their partner and felt more sexually attractive. They were also more willing to participate in physical activities and found it easier to find a good-fitting bra. The relatively long period between radiotherapy and AFT (median >3.5 years, extending to over 22 years) indicates that AFT could the main reason for improved scoring post-operatively. If that period had been shorter, the initial negative impact of radiotherapy would decrease during the study period, making time the main reason why the patients have higher scores after 2 years. Eleven of the patients had other ipsilateral surgical procedures performed. Seven of these were elective nipple operations leaving four patients who underwent surgery that could have positive or negative impact on the outcome. Only three of them were included in the MMRM analysis. Since these three patients had to undergo additional surgery one can speculate if they have scored more negatively. On the other hand, the additional surgery may have generated even better outcome. The patients had increased in BMI from 24.7 to 25.3 kg/m2 in median at the last follow-up. It is less likely that the small increase has an impact on the outcome.

Various aspects of AFT have been studied, but the number of studies using PROMs is modest. Most publications report only a one-item evaluation, asking the patient if she is satisfied with the outcome, often using a 3- to 5-point Likert scale [Citation8,Citation9,Citation17,Citation30]. In one study, 200 patients were asked personally about their degree of satisfaction with the surgical outcome at their post-operative follow-up. All of them claimed that they were satisfied or very satisfied, which may imply a significant systematic bias as the evaluation was not anonymous [Citation31]. In the present study, care was taken to prevent the surgeons involved from handling the post-operative questionnaires, so as not to influence the outcome measures.

In the only multi-centre cohort study, on this subject, Bennett et al. [Citation32] reported that AFT patients and ‘control patients’ scored similarly at baseline regarding physical well-being, satisfaction with the breast, sexual well-being and psychosocial well-being. Moreover, the control patients scored a little higher than the AFT patients (cases) at the 1-year follow-up. No difference between the two groups was seen after 2 years. However, almost 20% of the control patients had undergone AFT before baseline, which may lead to problems in the interpretation of the results. Moreover, no comparison was made of pre- and post-operative results. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that AFT provided measurable improvements in satisfaction, which is in line with our results.

In the present study, the nine items that can be regarded as indicators of aesthetic outcome and symmetry were all improved. The patients’ opinion of the aesthetic outcome could, therefore, be considered improved, which was one of the main reasons for performing AFT ( and ). It is difficult to assess the impact of breast surgery on sexuality, but this is important for the patient’s future well-being. Many breast cancer survivors suffer from impaired sexuality due to a change in body image [Citation33]. The results of this study indicate an improvement over time after AFT regarding feeling sexual attractive and comfortable when being naked. Whether this is due to AFT or the passage of time after cancer surgery and reconstruction is unclear. Our findings are in contrast to those in the study by Bennett et al., which showed a decrease in sexual well-being over time [Citation32]. However, we believe that the use of AFT as a complement to other breast surgical techniques may play a role in regaining a positive body image after surgery.

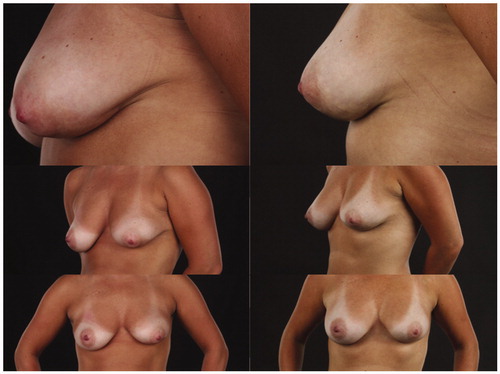

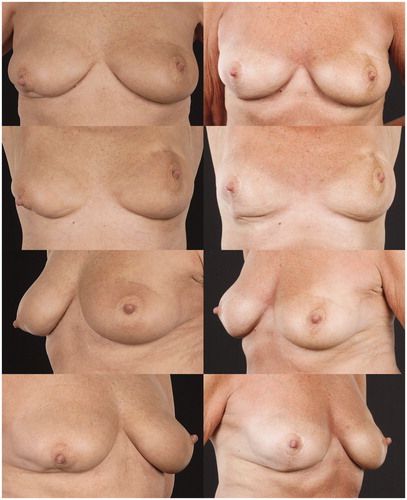

Figure 5. A 31-year-old women that presented with a scar retraction and volume deficiency 3.6 years after breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy (left). She underwent three AFT procedures with totally 150 ml fat. 2.2 years post-operative the scar is not visible and the symmetry is better (right).

Figure 6. A 66-year-old woman with bilateral defects after BCS and RT (left). Time from RT to AFT was 2.6 years for the left breast and 1 year for the right breast. She underwent two AFT procedures to each breast with totally 69 ml to the left side and 100 ml to the right. In addition, she underwent mastopexy on the right side. Post-operative images from the 2-year follow-up are shown to the right.

Improvement in softness of the breast is most evident at 6 months and 2 years in the mean line plots (Q13). A non-significant change in softness was seen after 1 year, in contrast to 2 years, indicating a slightly harder breast after 1 year. This could be explained by a reduction in the initial filling effect over the first year due to resorption of the transplanted fat. The improvement 2 years post-operatively could be a biological effect in radiation-damaged tissue, rather than primarily the effect of the filler. AFT has been suggested as a treatment for radiation-induced fibrosis, as clinical findings and experimental studies indicate reduced fibrosis when AFT is carried out after radiation therapy [Citation24,Citation34–37].

The patients, in the present study, reported a low level of pain before AFT. Despite this, reduced pain in the breast region was reported at the 2-year assessment. This finding, as well as increased breast softness, is in line with the results of a case-control study carried out by Panettiere et al. [Citation38] and implies that AFT not only improves the aesthetic outcome of a breast reconstruction but may also have a positive impact on morbidity after treatment for breast cancer.

No large difference was found in HRQoL between the study group and the reference population, either at baseline or after 2 years. There is, therefore, no reason to believe that the patients in the study group differ from an age-matched Swedish women in general when they decide to undergo AFT. Furthermore, it appears that AFT does not lead to a large decrease in HRQoL post-operatively.

The strengths of this study include the prospective design, with baseline data collected pre-operatively. However, the study has some limitations. First, the study group is relatively small. Furthermore, additional ipsilateral surgical procedures were performed at the same time in a minority of the patients, and this could have influenced their opinions concerning the result. However, the study group represents typical patients who undergo complementary AFT. Another limitation is that the heterogeneity of the patient group may have effect on the results. A sensitivity analysis was carried out and no difference in significance was seen comparing results from the entire patient group with the sub-group (92% of the patients) that had not undergone major additional ipsilateral surgery. No measurements of remaining fat volume were made post-operatively to compare with PRO.

A validated PROM would probably have made the evidence stronger but as mentioned before, no such was available at the start of the study. Lastly, several hypotheses tests were performed; hence, type I errors may exist.

In conclusion, the patient reported outcome improved up to 2 years after AFT, when the method was used as a complement in breast reconstruction or after breast-conserving surgery. Improved outcomes included better breast symmetry, size, shape and appearance. Autologous fat transplantation also increased the softness of the breast and reduced pain in the breast area. AFT did not affect HRQoL, and the study population did not differ from the reference population in this respect. The results of this study are of clinical importance for women considering AFT, to help them to make an informed decision. Nevertheless, further studies using PROMs after AFT and breast reconstructive surgery would be valuable to confirm our findings.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Elder EE, Brandberg Y, Bjorklund T, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in breast cancer patients after immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2005;14:201–208.

- Eltahir Y, Werners LL, Dreise MM, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes between mastectomy alone and breast reconstruction: comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:201e–209e.

- Rowland JH, Holland JC, Chaglassian T, et al. Psychological response to breast reconstruction. Expectations for and impact on postmastectomy functioning. Psychosomatics 1993;34:241–250.

- Barry M, Kell MR. Radiotherapy and breast reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:15–22.

- Kling RE, Mehrara BJ, Pusic AL, et al. Trends in autologous fat grafting to the breast. A National Survey of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:35–46.

- de Blacam C, Momoh AO, Colakoglu S, et al. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and aesthetic results after autologous fat grafting for contour deformities of the reconstructed breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:411e–418e.

- Kanchwala SK, Glatt BS, Conant EF, et al. Autologous fat grafting to the reconstructed breast: the management of acquired contour deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:409–418.

- Groen JW, Negenborn VL, Twisk DJ, et al. Autologous fat grafting in onco-plastic breast reconstruction: a systematic review on oncological and radiological safety, complications, volume retention and patient/surgeon satisfaction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:742–764.

- Delay E, Garson S, Tousson G, et al. Fat injection to the breast: technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:360–376.

- Lindegren A, Halle M, Docherty Skogh AC, et al. Postmastectomy breast reconstruction in the irradiated breast: a comparative study of DIEP and latissimus dorsi flap outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:10–18.

- Beesley H, Ullmer H, Holcombe C, et al. How patients evaluate breast reconstruction after mastectomy, and why their evaluation often differs from that of their clinicians. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1064–1071.

- Kim MS, Sbalchiero JC, Reece GP, et al. Assessment of breast aesthetics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:186e–194e.

- Wachter T, Edlinger M, Foerg C, et al. Differences between patients and medical professionals in the evaluation of aesthetic outcome following breast reconstruction with implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1111–1117.

- Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2013;346:f167.

- Ishaque S, Karnon J, Chen G, et al. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials evaluating the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Qual Life Res. Epub 2018/10/05.

- Kalaaji A, Bruheim M. Quality of life after breast reconstruction: comparison of three methods. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2010;44:140–145.

- Largo RD, Tchang LA, Mele V, et al. Efficacy, safety and complications of autologous fat grafting to healthy breast tissue: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:437–448.

- Schultz I, Lindegren A, Wickman M. Improved shape and consistency after lipofilling of the breast: patients' evaluation of the outcome. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46:85–90.

- Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18:386–388.

- Brandberg Y, Malm M, Blomqvist L. A prospective and randomized study, “SVEA,” comparing effects of three methods for delayed breast reconstruction on quality of life, patient-defined problem areas of life, and cosmetic result. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:66–74. discussion 5–6.

- Edsander-Nord A, Brandberg Y, Wickman M. Quality of life, patients' satisfaction, and aesthetic outcome after pedicled or free TRAM flap breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1142–1153. discussion 54–5.

- Gahm J, Jurell G, Edsander-Nord A, et al. Patient satisfaction with aesthetic outcome after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:332–338.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE. Jr. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey–I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med (1982). 1995;41:1349–1358.

- Rigotti G, Marchi A, Gali M, et al. Clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1409–1422. discussion 23–4.

- Agresti A. Kateri M. Categorical Data Analysis. In: Lovric M, editor. International encyclopedia of statistical science. Berlin (Heidelberg): Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. p. 206–8.

- Agha RA, Fowler AJ, Pidgeon TE, et al. The need for core outcome reporting in autologous fat grafting for breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77:506–512.

- Agha RA, Pidgeon TE, Borrelli MR, et al. Validated outcomes in the grafting of autologous fat to the breast: the VOGUE study. Development of a core outcome set for research and audit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:633e–638e.

- Pearl RA, Leedham SJ, Pacifico MD. The safety of autologous fat transfer in breast cancer: lessons from stem cell biology. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:283–288.

- Klinger M, Caviggioli F, Klinger FM, et al. Autologous fat graft in scar treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1610–1615.

- Bonomi R, Betal D, Rapisarda IF, et al. Role of lipomodelling in improving aesthetic outcomes in patients undergoing immediate and delayed reconstructive breast surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1039–1045.

- Sinna R, Delay E, Garson S, et al. Breast fat grafting (lipomodelling) after extended latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction: a preliminary report of 200 consecutive cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1769–1777. Epub 2010/01/19.

- Bennett KG, Qi J, Kim HM, et al. Association of fat grafting with patient-reported outcomes in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:944–950.

- Pelusi J. Sexuality and body image. Research on breast cancer survivors documents altered body image and sexuality. Am J Nurs. 2006;106:32–38.

- Costantino A, Fioramonti P, Ciotti M, et al. Lipofilling in skin affected by radiodermatitis: clinical and ultrasound aspects. Case report. G Chir. 2012;33:186–190.

- Garza RM, Paik KJ, Chung MT, et al. Studies in fat grafting: Part III. Fat grafting irradiated tissue–improved skin quality and decreased fat graft retention. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:249–257.

- Mojallal A, Lequeux C, Shipkov C, et al. Improvement of skin quality after fat grafting: clinical observation and an animal study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:765–774.

- Kumar R, Griffin M, Adigbli G, et al. Lipotransfer for radiation-induced skin fibrosis. Br J Surg. 2016;103:950–961.

- Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D. The serial free fat transfer in irradiated prosthetic breast reconstructions. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33:695–700.