ABSTRACT

Background: The professional approach of sexual assault victims has changed since the 1970s: from a fragmented model to a centralised ‘gate management model’, where multiple disciplines offer collaborative services at one central location. Like other countries across the globe, the Netherlands took steps towards an integrated, multi-agency support framework for victims of sexual assault.

Objective: The objective of this paper was threefold: (1) to describe the development of the multidisciplinary Sexual Assault Centres (SAC) in the Netherlands, (2) to assess the characteristics of victims who attended the SAC, and the services they used (3) to analyse Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of the current framework (SWOT).

Method: The development of the national network of SAC was described. Data on victims presenting at the SACs were routinely collected between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2020. This data from the sixteen sites was combined and analysed. Also, a SWOT analysis of the SAC was performed.

Results: The SAC was established between 2012 and 2018. From 2016 through 2020 almost 16,000 victims of sexual assault contacted one of the 16 SACs. The data show a steady increase in yearly cases, with a consistently high use of medical and psychological services. The SAC has several strengths, such as its accessibility, and opportunities, such as increasing media attention, that underline its quality and relevance. However, the SAC's inability to reach certain minority groups and the current financial structure are its main weakness and threat.

Conclusions: Despite the growing number of victims attending the SAC and the increasing awareness of the benefits of an immediate multidisciplinary response to sexual assault, there are still deficiencies in the SAC. The SAC continues to work on these deficiencies in order to optimise efficient and effective care for all victims of sexual assault.

HIGHLIGHTS

The Dutch Sexual Assault Centres established a national network that provides medical, forensic, and psychological services for victims, and despite of its strengths and opportunities, faces threats and weaknesses that underline the importance of further development.

Antecedente: El abordaje profesional a las víctimas de agresiones sexuales ha cambiado desde la década de 1970, desde un modelo fragmentado hacia un modelo centralizado de ‘administración de compuertas’. En este modelo, diferentes disciplinas ofrecen servicios de forma colaborativa en un solo lugar. Así como en muchos países del mundo, los Países Bajos han dado pasos hacia un modelo de soporte integrado y multisectorial para las víctimas de agresiones sexuales.

Objetivo: El objetivo de este artículo es triple: (1) describir el desarrollo de los centros multidisciplinarios para el abordaje de las agresiones sexuales (CMAAS) en los Países Bajos, (2) evaluar las características de las víctimas que acuden a los CMAAS,y los servicios que utilizan y, (3) analizar las fortalezas, oportunidades, debilidades y amenazas (FODA) de los servicios brindados en el modelo actual.

Métodos: Se describe el desarrollo de la red nacional de CMAAS. La información de las víctimas que acudieron a los CMAAS se recolectó de forma rutinaria entre el 1 de enero del 2016 y el 31 de diciembre del 2020. Se combinó y analizó la información de dieciséis centros. Asimismo, se realizó un análisis FODA de los CMAAS.

Resultados: Los CMAAS se implementaron entre 2012 y 2018. Desde el 2016 hasta el 2020, casi 16 000 víctimas de agresiones sexuales se contactaron con alguno de los dieciséis CAAMS. La información recolectada muestra un incremento constante en el número de casos anuales, consistente con un alto uso de los servicios médicos y psicológicos. Los CAAMS tuvieron varias fortalezas, tales como su accesibilidad, y oportunidades, tales como la atención de los medios de comunicación que resaltan su calidad e importancia. No obstante, la incapacidad de los CAAMS de alcanzar ciertos grupos minoritarios y la estructura financiera actual fueron su principal debilidad y amenaza, respectivamente.

Conclusiones: A pesar de un número creciente de víctimas que acuden a los CAAMS y a un incremento en la sensibilización de los beneficios de una respuesta inmediata y multidisciplinaria frente a la agresión sexual, aún hay deficiencias en los CAAMS. Estos continúan trabajando para superar estas deficiencias, de modo que se pueda optimizar un cuidado eficiente y efectivo para todas las víctimas de agresión sexual.

背景:自 1970 年代以来,性侵犯受害者的专业方法发生了变化:从分散模式到集中的‘门禁管理模式’,其中多个学科在一个中心位置提供协作服务。与全球其他国家一样,荷兰一步步为性侵犯受害者建立了一个多机构的综合支持框架。

目的:本文有三个目的:(1)描述荷兰多学科性侵犯中心(SAC)的发展,(2)评估参加 SAC 的受害者的特征及其所使用服务,(3) 分析当前框架的优势、劣势、机会和风险(SWOT)。

方法:描述了SAC全国网络的发展情况。在 2016 年 1 月 1 日至 2020 年 12 月 31 日期间,例行收集了参与 SAC受害者的数据。对这个来自 16 个站点的数据进行了合并和分析。此外,对 SAC 进行了 SWOT 分析。

结果:SAC 成立于 2012 年至 2018 年。从 2016 年到 2020 年,近 16,000 名性侵犯受害者联系了 16 个 SAC 之一。数据显示,每年病例稳步增加,医疗和心理服务的使用率一直很高。 SAC 有几个优势,例如它的易得性和机会,例如增加媒体关注度,这加强了其质量和相关性。然而,SAC 无法触及某些少数群体以及当前的经济结构是其主要劣势和风险。

结论:尽管参与 SAC 的受害者越来越多,并且人们越来越意识到对性侵犯及时、多学科应对方法的好处 SAC 仍然存在缺陷。 SAC 继续努力解决这些缺陷,以优化对所有性侵犯受害者的高效护理。

There is clear evidence that sexual assault is related to serious mental health problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, substance abuse, major depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Fergusson et al., Citation2013) as well as physical health problems, including anogenital injuries, sexually transmitted infections (STI's), unwanted pregnancy, chronic pelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction (Linden, Citation2011; Paras et al., Citation2009). Both from an individual as well as a societal point of view, it is important to prevent the negative effects of sexual assault by providing psychological and medical care as early as possible post-assault. Ideally, these services should be integrated with forensic examination to minimise the burden for the victim.

Currently, in many countries acute victims of sexual assault profit from a centralised ‘gate management model’ where professionals from medical, forensic, and psychosocial disciplines offer collaborative services at one central location both in the direct aftermath of the assault as during follow-up. For example, in the United States, the gate model was put into practice by Sexual Assault Response Teams (SARTs) in the 1970s. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the Nordic countries were inspired by SARTs and started to establish rape crisis centres (Bang, Citation1993; Heimer et al., Citation1995). The United Kingdom set up its first Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) in 1986, followed by the establishment of many SARCs across the country (Lovett et al., Citation2004).

The benefits of the gate model have been studied showing a decrease of the psychological and physical impact of sexual assault (Martin et al., Citation2007) and higher chances to apprehend the offender (Campbell et al., Citation2008; Campbell et al., Citation2012). Therefore, the model is recommended by both the World Health Organisation (WHO, Citation2003) and experts (Eogan et al., Citation2013; Greeson & Campbell, Citation2013).

This paper describes the development towards a national network of Sexual Assault Centres (SAC) in the Netherlands, including data on victims and their use of services. Also, it includes an analysis of the network's strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, which forms the basis for its future development.

1. The development towards a national network

Already in 1999, the Dutch government was advised by researchers to set up a network of sexual assault centres in the Netherlands (Ensink & Van Berlo, Citation1999). At that time, victims of sexual assault had to consult different agencies at various locations, which increased the risk of victims dropping out of the system. Furthermore, victims were confronted with waiting-lists and a lack of expertise. It was found that this system slowed down the recovery process (Ensink & Van Berlo, Citation1999). In response to these urgent issues, in 2012 the first Dutch multidisciplinary SAC was established. During this time, the awareness of the multidisciplinary approach in the management of acute rape increased in the Netherlands among clinicians and policymakers (Vanoni et al., Citation2013). Following this shift, more multidisciplinary SACs were set up to ensure its availability and accessibility throughout the Netherlands. Since 2018, a national network of SACs is operational at 16 designated sites that are accessible 24/7 and reachable within an one hour driving distance. The majority of the SACs is integrated into hospital-based Emergency Departments.

1.1. The multidisciplinary model

Typical for SACs is the close partnership between hospitals, municipal health services, psycho-social services, and the police, resulting in a combination of medical and psychological care with forensic examination to collect evidence. The SAC aims for efficiency with minimal mobilisation of the victim, minimisation of testimonial mistakes and discrepancies, and avoidance of unnecessary additional stress for the victim. For example, victims are not asked to explain what happened to them more often than strictly necessary. Also, medical care and forensic medical examination are integrated to minimise the victims’ potential burden, for example by asking to undress only once.

The multidisciplinary approach focuses on victims who contact the SAC within seven days after the assault. Additionally, the SAC can also be contacted in the period after seven days for psychoeducation and advice. The SAC is accessible without a referral or police involvement. The SAC can be reached by a national telephone number (free of charge) that is operated 24/7 by trained specialists, who connect the victim to the nearest SAC site to ensure care as soon as possible. At the first presentation to a SAC (i.e. day zero), victims first meet a trained (forensic) nurse or health care professional who will stand by the victim through all medical and forensic examinations and helps to create a safe haven. Victims can also make use of the medical and psychological services of the SAC without reporting the assault to the police.

1.1.1. Forensic examination

Those who consider reporting the assault to the police can receive a forensic examination to collect evidence and to document the injury, followed by medical care. In the case of physical injuries that need an immediate response, these will be treated first. The forensic examination is performed at the SAC by a forensics physician in accordance with the guidelines of the Netherlands Forensic Institute and the Dutch Forensic Medical Society (Forensisch Medisch Genootschap, Citation2016). A forensic examination can only be initiated by the police department for sexual offences in agreement with the victim. This department remains solely responsible for the investigation of the crime and documentation is not shared with the SAC. Although the detectives work together with the health care professionals in coordinating the forensic medical examination and medical care, police interrogation remains independent from the SACs. It is of note that all cases of victims who receive a forensic examination are filed by the police, but victims are not obligated to make an official report to the police at this time. Reports to the police can be made at any stage.

The forensic physician collects forensic evidence using a ‘rape kit’. During the examination, swabs are taken in an attempt to find DNA of the perpetrator, mostly from sperm, blood or saliva. Time frames for collecting evidence are dependent on the acts, the location on the body, the use of condoms, ejaculation and bathing after the incident. In general, time frames range between 48 h after the incident for skin to seven days for the vagina (Mayntz-Press, et al., Citation2008). Bathing or cleaning the anogenital region is common after sexual assault. Although this lowers the probability of catching DNA from the perpetrator, it is no valid reason to omit the forensic examination. The locations that are swabbed depend on the history provided and on the locations of injuries. Anogenital and oral swabs are almost always used. Breasts, neck and nails are also common locations for swabs. Clothes and hair can be secured for DNA examination as well. Anogenital injuries can also provide forensic value, particularly in children who are not sexually active. In acute situations, toxicological examination of blood and urine can provide important information. Lastly, STIs can have forensic importance. In particular situations, determining STIs in both the victim and the perpetrator can provide evidential power.

1.1.2. Medical services

The medical team consists of at least one physician who is specialised in infectious disease or gynaecology, an emergency room physician, or a paediatrician. Medical care consists of three parts. First, potential injuries and pain are examined and treated. Second, victims receive screening and (preventative) treatment of STIs following the national guidelines of the Dutch Society for Paediatrics (Nederlandse Vereniging Kindergeneeskunde, Citation2016) and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (RIVM, Citation2020). This includes post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and hepatitis B vaccination if needed. It is recommended not to treat for chlamydia and gonorrhoea prophylactically, but to test at presentation and at follow-up after two weeks. Follow-ups entail screening for syphilis, hepatitis B, and HIV at two weeks and three months post-assault and screening of HIV at six month post-assault for adults who were prescribed PEP. The SAC also offers information, counselling and treatment for the victim and their partner when an STI is diagnosed. The third part of the medical care is pregnancy prevention. Emergency contraception and pregnancy tests are provided when indicated. Victims who are pregnant are referred to specialist care. It is a standard procedure to inform the victim's general practitioner about the medical care provided by the SAC.

1.1.3. Psychological services

One day after admission to the SAC, (i.e. day one), victims are contacted by a casemanager via telephone or face-to-face. Casemanagers do not ask for details of the assault or for the victims to express their feelings, in order to refrain from psychological debriefing and its potentially harmful effects (Rose et al., Citation2002). As post-traumatic stress symptoms often alleviate within the first month after rape (Rothbaum et al, Citation1992), the SACs operate under the ‘watchful waiting’ principle, meaning that psychological treatment is withheld to prevent interference with natural recovery. Instead, psychological services of the SAC consist of psychoeducation and trauma screening by a casemanager during the first four weeks post-assault, combined in a three-step watchful waiting protocol. This active monitoring during the first month after a traumatic event is supported by the most recent NICE guidelines (NICE, Citation2018) for people with subthreshold PTSD. For those meeting the diagnostic threshold for PTSD, there is evidence for the effectiveness of trauma-focussed cognitive behavioural therapy as an early intervention (Roberts et al., Citation2019). However, almost all victims of sexual assault meet this diagnostic threshold immediately after the assault (Covers et al., Citation2021; Steenkamp et al., Citation2012) and evidence for the effectiveness of early intervention for this group specifically is limited (Covers et al., Citation2021, Oosterbaan et al., Citation2019).

In the first step, the casemanagers make an assessment of the victims’ current safety, social support system, risk behaviour (use of substances and self-harm) and current psychological functioning. The second step entails psychoeducation about normal stress responses during and after sexual assault as well as trauma processing. This psychoeducation extents to parents, partners, or other persons who are close to the victim. Finally, casemanagers aim to reduce potential stress caused by contact with medical professionals or police. They also refer the victims to specialists when legal counselling is needed.

At two and four weeks post-assault, victims are contacted again by the casemanager. The casemanagers repeat the three steps and screen for PTSD using the Children's Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES-13; Verlinden et al., Citation2014) for children and the Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ; Brewin et al., Citation2002) for adults. When indicated, victims are referred directly for evidence-based PTSD treatment, such as EMDR therapy or Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (ISTSS, Citation2018).

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

Since 2016, all sites of the SAC register anonymized information about the victims and their service use. This data is collected for the purpose of the yearly SAC reports. The present study describes the data collected between January 2016 and December 2020 on victims who attended the SAC in person. All data was anonymized and included no specific details of the victims. Victims verbally consented to the collection of this anonymized data. According to the Ethical Medical Committee of University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Declaration of Helsinki and the Dutch Medical Research involving Human Subjects Act are not applicable to the present study since it uses anonymized patient files. Data was collected by the coordinators of each SAC location, who informed the researcher about the number of victims and victim characteristics at their centre.

For the purpose of analysing the quality and potential of the current network of SACs, a Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis was realised. The Strengths and Weaknesses describe helpful and harmful aspects of the network that find its origin within the organisation, whereas the Opportunities and Threats are helpful and harmful aspects that originate from outside of the organisation.

2.2. Measures

All victims characteristics were coded as binary variables. To protect the victims anonymity, age was recoded into older or younger than 18. Victim characteristics further included gender and prior victimisation at first presentation to SAC. Prior victimisation was measured by asking the victim if they had ever experienced any form of sexual assault before. Service characteristics included forensic examination, the use of medical care, reporting to the police, and the use of psychological care (whether or not victims received watchful waiting by their casemanager).

2.3. Data analysis

For the victim profile and service use, the frequencies across all SAC location were produced. Most variables had no missing values, with the exception of prior victimisation and reporting to the police. It was only known how many victims had experienced prior victimisation and how many had reported to the police. However, it was not known whether the other victims had not experienced prior victimisation or reported to the police, or whether they had refused to answer this question or the question was not asked. Therefore, these statistics may be an underrepresentation. The authors deliberated on the four quadrants of the SWOT analysis. A SWOT analysis is designed to facilitate a realistic, fact-based, data-driven look at the strengths and weaknesses of an organisation. The organisation needs to keep the analysis accurate by avoiding pre-conceived beliefs or grey areas and instead focusing on real-life contexts. A SWOT analysis should be used as a guide and not necessarily as a prescription.

3. Results

3.1. Victim profile and service use

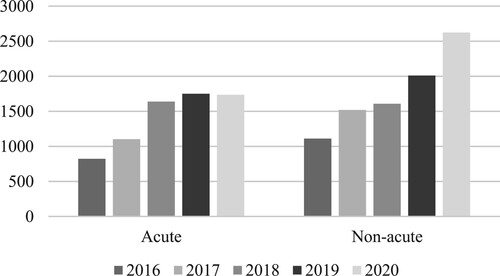

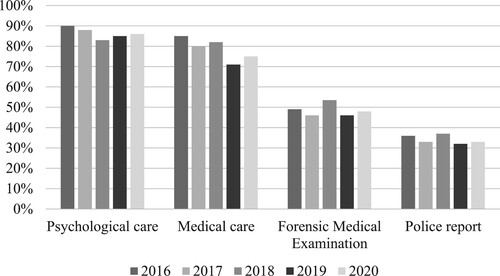

From 2016 through 2020, a total of 15,936 victims of sexual assault contacted the Dutch SACs. Of these victims, 7,056 contacted the SACs within seven days after the assault (i.e. acute cases) and were therefore eligible for the multidisciplinary approach consisting of medical care, forensic examination, and psychological care. The other victims (n = 8,880) contacted the SACs after these seven days (i.e. non-acute cases) for psychoeducation or advise. shows an increase in both acute and non-acute cases over the years. It should be noted that the expansion of the national network prior its completion in 2018 accounts partly for the increase in cases. Notably, the increase in acute cases stabilised in 2020, while the non-acute cases show a large increase relative to 2019. Between 2016 and 2020, the percentage of acute victims under the age of 18 has been stable at 31%. Every year, one in four victims reports having experienced prior sexual violence. Data on victim gender were collected since 2017 and shows that victims are primarily female, with the percentage of male victims fluctuating between 8% and 12%. The victims’ service use within the SACs per year can be found in . Most victims receive medical and psychological care (on average 78% and 86%, respectively). Moreover, on average 49% of acute victims have a forensic medical examination at the SAC, and 34% make a police report.

3.2. SWOT analysis

3.2.1. Strengths

The multidisciplinary network of SACs in the Netherlands has several strengths. First, the centres are easily accessible via telephone and chat. The network has expanded rapidly over the last few years, resulting in the 16 current centres that are dispersed nationwide in such a way that every victim can find a centre within a one hour driving distance from anywhere in the Netherlands. The national telephone number is available 24/7, ensuring that calls are answered at any time of day. The chat is available outside working hours to ensure that victims can contact a professional at any time of day. Both the national telephone number and the chat are free of charge and can be used anonymously.

A second strength of the national network of SACs is the strong alliance with the national police department of sexual offences, connecting the patient and victims aspects of sexual assault victimisation. The standard working procedures of the centres and the police department of sexual offences are intertwined. This guarantees that acute victims who contact the police about the assault will always be referred for medical and psychological care, and vice versa.

Third, all SACs adhere to the same standard of quality. The network of SACs and the 35 Dutch central municipalities have developed and signed the criteria for service quality of the SACs. This document binds all centres to a high quality of multidisciplinary medical, forensic, and psychological services and ensures that all victims receive the same services, regardless of which centre they are referred to. Furthermore, all professionals in the SAC receive regular training to ensure the understanding of and adherence to the quality criteria.

3.2.2. Weaknesses

We have found various weaknesses in the current network of the SACs. First, there are concerns for whether the SACs sufficiently address all victims. Victims who refer to the SACs are mainly female adolescent and young adult victims. However, men and older adults are also victimised by sexual assault (Lowe & Rogers, Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2019). Moreover, studies have found that LGBTQI+ people (de Graaf & Wijsen, Citation2017), people with disabilities (Casteel et al., Citation2008), and people with substance abuse problems (Messman-Moore & Brown, Citation2009) are at high risk for experiencing sexual assault. Yet, the SACs do not seem to be sufficiently accessible for these persons.

Second, we have concluded that the forensic medical examination is not performed in a standard way for children and adults. Children until the age of 15 years are routinely assessed top-to-toe whereas adults are not. For adult victims, the focus of the forensic medical examination now depends on the victims’ narrative to the police, which may impact the collection of evidence and the documentation of injuries (Ingemann-Hansen et al., Citation2008). Current forensic services may be improved with the use of standard top-to-toe forensic medical examinations for victims of all ages, in line with international guidelines (The Faculty for Forensic & Legal Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians [FFLM], Citation2021).

Third, although evidence-based treatment for PTSD is ensured for those who present at the SAC immediately after rape, for persons who have experienced abuse longer than seven days ago, the SAC experiences challenges in referring victims to appropriate mental health services because of waiting-lists.

3.2.3. Opportunities

Several opportunities were found that benefit the SACs. First, in 2011, the Council of Europe opened the Istanbul Convention: a new treaty on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. This treaty was signed by the Netherlands in 2015 and went into force in 2016. The Istanbul Convention is an opportunity for the Dutch SACs, because the government is obligated to take measures to prevent, investigate, punish and provide reparation for gender-based violence (Article 5) and to ensure that victims have access to services facilitating their recovery from violence (Article 20) (Istanbul Convention, Citation2011). Specifically for sexual assault, the Istanbul Convention declares that states need to provide ‘sexual assault referral centres for victims in sufficient numbers to provide for medical and forensic examination, trauma support and counselling for victims’ (Article 25). The Istanbul Convention is highly relevant to the SACs as it obliges the government to develop proper care for victims of sexual abuse. Further implementation of this treaty by the state can aid the network of SACs with policies (Article 7) and financial resources (Article 8).

A second opportunity for the network of SACs is the international media attention for sexual assault through #MeToo, a twitter hashtag about sexual harassment and assault that went viral in October of 2017, followed by #metooincest in 2021. The hashtag publicly confirmed that sexual assault is not a rare phenomenon, but an everyday reality for many people. Following #MeToo, the media attention for the Dutch SACs increased as well, with interviews and appearances in television programs, newspapers, podcasts, magazines and social media. It is likely that this attention for the SACs had improved public awareness, as a sharp increase in the number of acute SAC referrals was found between 2017 and 2018 (). More recent, television show The Voice of Holland has been pulled off the air in January 2022 amid allegations of sexual misconduct by various employees of the show that are now being investigated by the police. Since this scandal broke, the number of chats and phone calls to the SACs has risen significantly and the police department of sex crimes reported an increase in police reports of over 25%.

Third, in November 2020, the Dutch Minister of Justice and Security declared that the law on sexual assault will be reformed in response to changing social attitudes towards sex and sexual violence. The proposed reform also aims to bring Dutch law in line with the requirements of the Istanbul Convention. Currently, the Dutch criminal law defines rape as the ‘actions comprising or including the sexual penetration of the body’ that have taken place by force (Art. 242). Force is specified as ‘coercion through violence, the threat of violence or through another act or the threat of another act’. In this definition, force and violence are crucial aspects for criminal prosecution. However, research has shown that 70% of victims experience tonic immobility: a temporary state of motor inhibition (Möller et al., Citation2017). This ‘tonic immobility’ eliminates the need for force and violence. The new bill implies that all forms of non-consensual sex will now be classed as rape. This new definition poses an opportunity for the SACs. When sexual assault without physical or verbal violence is recognised as a criminal offence, victims of these assaults may feel less reserved to contact the SACs for help.

Finally, a new type of sexual violence is increasing rapidly in numbers. Police and mental health professionals are becoming more aware of the negative impact of online or cyber sexual violence such as sexting, sextortion and digital grooming. Similar to sexual abuse in real-life, online sexual abuse is associated with a broad range of behavioural and psychological characteristics (Frankel et al., Citation2018). Also, online sexual violence may result in hands-on sexual activities or in other physically harmful situations that need immediate medical care. Therefore, the SAC network is an opportunity to respond adequately to this new type of traumatisation.

3.2.4. Threats

The main challenge SAC has faced is the financing of its services and activities. The Dutch Foundation for Victims (Fonds Slachtofferhulp) enabled the running costs for the first years. In later years, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport as well as the Ministry of Justice financed the centres. Due to decentralisation of several aspects of health care, 35 municipalities are financially responsible since 2018 for the regional centres as well as the national activities such as phone number and website. This structure is risky because negotiating with 35 municipalities about finances threatens the uniformity of the services delivered by SAC. Discrepancies have been identified between the 16 regional centres with regard to available housing, staffing, and finances (Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport, Citation2020). These differences are the result of local structures that have historically been built in a certain way. This should not be problematic per se as all centres follow the national quality criteria. However, considering the recent increase of number of victims referred to the centres, differences between centres can threaten quality of care provided in the near future.

A second threat concerns the embedding of the SACs at the Emergency Departments of hospitals implying that use of the SAC is not free of charge. In the Netherlands, it is mandatory to have at least a basic health insurance with a compulsory ‘own-risk’ excess of a minimum of 385 euros per year, meaning that adult citizens pay the first 385 euros of their yearly medical bills (excluding GP visits) before the insurer pays. Therefore, adult victims of sexual assault may have to pay part of the medical costs from their SAC visit. So, this directly threatens the accessibility of the SACs. Recently, a pilot study was run by the Ministry of Justice from 2020–2021 where the government repaid these costs to victims. The aim of this pilot was to explore to what extent this process can reduce victims’ thresholds for SAC use. The findings are yet to be published.

4. Conclusion

Inspired by international developments towards a multidisciplinary approach for acute victims of sexual assault, a network of 16 SACs was established in the Netherlands by 2018. Typical for the SAC is the close partnership between hospitals, municipal health services, psycho-social services and the police who cooperate according to protocols establishing optimal conditions for forensic evidence collection, medical services and psychological care, in accordance with the Istanbul Convention and the international guidelines. This national network of SACs provides expertise and clarity for victims about where to get help and reduces the likelihood of victims dropping out of the system because of waiting-lists and large travel distances.

From 2016 through 2020 almost 16,000 victims of sexual assault contacted the SAC. Ever since its existence, there is a yearly increase in the number of persons admitted to the SAC. Notably, in 2020 the increase in acute cases stabilised while the number of non-acute cases saw a sharp incline. This may be a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, as social isolation due to lockdowns may have motivated people who were victimised a longer time ago to contact the SAC, while the pressures on the health care system may have prevented acute victims from seeking help. Additionally, social isolation may have reduced the incidence of date-rape and (alcohol-induced) sexual assault in nightlife. Over the years, the acute victims were primarily female, as is the case in most international SACs (Bang, Citation1993; Kerr et al., Citation2003; Larsen et al., Citation2014). One-third of the victims were minors. This incidence is higher than in other SACs (Kerr et al., 2003; Larsen et al., Citation2014), but this discrepancy is most likely caused by differences in the definition of ‘minor’ and the organisation of child health care. In the Netherlands, victims of all ages can make use of SAC services, and minors are defined as younger than 18. Prior assault was reported by one in four victims. Similarly, other SACs observed that approximately a third of their victims experienced prior sexual assault (Larsen et al., Citation2014; Vik et al., Citation2019).

Between 2016 and 2020, the service utilisation was overall noted as high with a majority of victims receiving medical care and psychological care. Over time, the multidisciplinary service use among victims has remained stable. The existence of specialised services in combination with a close collaboration with the police may lead to a higher utilisation of services, as has been suggested in previous research (Greeson & Campbell, Citation2013). Notably, the percentage of police reporting in the SAC stands in sharp contrast to the national reporting rates for sexual assault which are estimated to be as low as 10% (Merens et al., Citation2012). Although the police is the primary source for referrals to the SAC and a high reporting rate is thus to be expected, the multidisciplinary approach may facilitate police reporting because victims feel acknowledged in an environment where experts work closely together. Summarised, the high use of services at the Dutch SAC confirms the need for comprehensive care for victims of sexual assault and thus the appropriateness of the SAC model.

The SWOT analysis shows that the Dutch SAC network has achieved 24/7 accessible care, characterised by a strong cooperation with the police. The primary internal weakness of the network is its outreach towards at-risk and minority groups. For future developments, the SACs aim to launch educational campaigns aimed at victims in these groups. There are several external factors that pose an opportunity or threat for the network. The attention for sexual assault in the media, politics, and law give the SACs opportunity to promote and further develop their services. However, lack of finances impedes progression. The current system of financing by municipalities has led to discrepancies in the finances, housing, and staffing per centre. To achieve uniformity in the quality of care, the multidisciplinary network needs an increase in budget as well as centralisation of the SACs finances. Without increased (centralised) funding, the quality of the care that the SAC provides may be at risk. Yet, the SAC aims to continue its growth and development by working through its challenges.

Given the opportunities from this SWOT analysis, an increase in victims attending the SAC is projected for the near future. For example, it is plausible that the changing law on sexual assault lowers the threshold for disclosure and help-seeking. Crucially, the SAC has to move alongside these changes to prevent fragmentation of care, by solidifying its position as the central point of all sexual assault related information and services in the Netherlands. As such, the SAC aims to extend its focus to include all aspects of sexual assault, including suspicion of sexual abuse in children, online sexual assault, and non-acute victim care.

There are several limitations to this study. First, several variables may be underestimated due to method of data collection. For example, the SACs may not always ask victims whether they have experienced prior sexual assault. Also, victims may refuse the psychological services of the SAC because they already have a mental health care provider. Additionally, victims may file a police report at a later date. Second, the study lacked information to provide a complete victim profile. While each SAC site collects information on baseline and outcome physical and psychological health of its victims, patient confidentiality impedes us from combining this information into a central SAC database. Likewise, the outcome of the police reports is collected by the police but not shared with the SAC. Prospective longitudinal research taking these components into account is needed to further delineate the impact of SAC.

The services of the SAC are in need of further research. Firstly, it is unknown if and how the SAC contributes to police reporting and the outcomes of legal trials. Secondly, it is yet to be determined whether the psychological services contribute to the victims’ well-being. Recent research comparing victims who received these services to victims who received early intervention using EMDR therapy, found that PTSD symptoms decrease equally after both groups, and more than in comparable studies (Covers et al., Citation2021). This may indicate that the psychological services of the SAC aid the recovery of victims of sexual assault. However, further research is needed to determine the working elements of these services. Lastly, future research ought to examine the opinions about the SAC of the referred victims. Their satisfaction, needs and ideas are crucial for determining the successfulness of the SAC.

In conclusion, this study improved our understanding of the victims using the SACs and its services. The increasing attendance of victims of sexual assault together with a good uptake of the services offered, encourage further development of the multidisciplinary approach of rape victims in Dutch SACs, especially since the upcoming reforms of the Dutch law on sexual assault is expected to result in more victims to present at the SAC.

Ethical statement

Victims verbally consented to the collection of anonymized data. According to the Ethical Medical Committee of University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Declaration of Helsinki and the Dutch Medical Research involving Human Subjects Act are not applicable to the present study since it uses anonymized patient files.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the sensitivity of the sample of this study, data will not be made available.

References

- Bang, L. (1993). Who consults for rape? Sociodemographic characteristics of rape victims attending a medical rape trauma service at the Emergency Hospital in Oslo. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 11(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813439308994895

- Brewin, C. R., Rose, S., Andrews, B., Green, J., Tata, P., McEvedy, C., Turner, S., & Foa, E. B. (2002). Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(2), 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.2.158

- Campbell, R., Patterson, D., Adams, A. E., Diegel, R., & Coats, S. (2008). A participatory evaluation project to measure SANE nursing practice and adult sexual assault patients’ psychological well-being. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 4(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-3938.2008.00003.x

- Campbell, R., Patterson, D., & Bybee, D. (2012). Prosecution of adult sexual assault cases A longitudinal analysis of the impact of a sexual assault nurse examiner program. Violence Against Women, 18(2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212440158

- Casteel, C., Martin, S. L., Smith, J. B., Gurka, K. K., & Kupper, L. L. (2008). National study of physical and sexual assault among women with disabilities. Injury Prevention, 14(2), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip.2007.016451

- Covers, M. L. V., de Jongh, A., Huntjens, R. J. C., de Roos, C., van den Hout, M., & Bicanic, I. A. E. (2021). Early intervention with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to reduce the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms in recent rape victims: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1943188. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1943188

- De Graaf, H., & Wijsen, C. (2017). Seksuele gezondheid in Nederland 2017. [Sexual Health in the Netherlands]. Rutgers.

- Ensink, B., & Van Berlo, W. (1999). Indringende herinneringen. De ontwikkeling van klachten na een verkrachting [Intrusive memories: Development of psychological problems after sexual assault]. NISSO/Eburon.

- Eogan, M., McHugh, A., & Holohan, M. (2013). The role of the sexual assault centre. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.010

- The Faculty for Forensic & Legal Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians [FFLM]. (2021). Recommendations for the Collection of Forensic Specimens from Complainants and Suspects. Author.

- Fergusson, D. M., McLeod, G. F., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: Findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse & Neglect, 2134(13), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.013

- Forensisch Medisch Genootschap. (2016). Richtlijn Forensisch Medisch Onderzoek bij zedendelicten [Guidelines forensic medical examination for sex crimes]. Author.

- Frankel, A. S., Bass, S. B., Patterson, F., Dai, T., & Brown, D. (2018). Sexting, risk behavior, and mental health in adolescents: An examination of 2015 Pennsylvania youth risk behavior survey data. Journal of School Health, 88(3), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12596

- Greeson, M., & Campbell, R. (2013). Sexual Assault Response Teams (SARTs): an empirical review of their effectiveness and challenges to successful implementation. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 14(2), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012470035

- Heimer, G., Posse, B., Stenberg, A., & Ulmsten, U. (1995). A national center for sexually abused women in Sweden. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 53(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7292(96)80007-5

- Ingemann-Hansen, O., Brink, O., Sabroe, S., Sorensen, V., Vesterbye Charles, A. (2008). Legal aspects of sexual violence - Does forensic evidence make a difference? Forensic Science International, 180, 98-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.07.009

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Guidelines Committee [ISTSS]. (2018). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Prevention and Treatment Guidelines Methodology and Recommendations. Author.

- Istanbul Convention. (2011). Council of Europe Convention of preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. CETS No.210.

- Kerr, E., Cottee, C., Chowdhury, R., Jawad, & Welch, J. (2003). The Haven: A pilot referral centre in London for cases of serious sexual assault. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 110, 267-271. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.02233.x

- Larsen, M. L., Hilden, M., & Lidegaard, O. (2014). Sexual assault: A descriptive study of 2500 female victims over a 10-year period. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 122, 577-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13093

- Lee, J. A., Majeed-Ariss, R., Pedersen, A., Yusuf, F., & White, C. (2019). Sexually assaulted older women attending a U.K. sexual assault referral centre for a forensic medical examination. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 68, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101859

- Linden, J. A. (2011). Care of the adult patient after sexual assault. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(9), 834–841. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1102869

- Lovett, J., Regan, L., & Kelly, L. (2004). Sexual Assualt Referral Centres: Developing good practice and maximizing potentials. Home Office Research Study 285. Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, Home Office.

- Lowe, M., & Rogers, P. (2017). The scope of male rape: A selective review of research, policy and practice. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 35, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.06.007

- Martin, S., Young, S., Billings, D., & Bross, C. (2007). Health care-based interventions for women who have experienced sexual violence: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 8(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838006296746

- Mayntz-Press, K. A., Sims, L. M., Hall, A., & Ballantyne, J. (2008). Y-STR profiling in extended interval (>3 days) postcoital cervicovaginal samples. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 53(2), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00672.x

- Merens, A., Hartgers, M., & Van den Brakel, M. (2012). Emancipatiemonitor 2012. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau & Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/dossiers/vrouwenenmannen/publicaties/publicaties/archief/2012/emancipatiemonitor2012-pub.html.

- Messman-Moore, T. L., & Brown, A. L. (2009). Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(3), 499–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508317199

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. (2020). Onderzoek Financiering Centrum Seksueel Geweld: Eindrapportage [Research on Financing of Sexual Assault Centres: Final Report]. Gupta Strategists.

- Möller, A., Söndergaard, H. P., & Helström, L. (2017). Tonic immobility during sexual assault: A common reaction predicting post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavia, 96(8), 932–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13174

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence [NICE]. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder: Evidence reviews on care pathways for adults, children and young people with PTSD (NICE Guideline Standard No. NG116). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116.

- Nederlandse Vereniging Kindergeneeskunde. (2016). Richtlijn diagnostiek bij (een vermoeden van) seksueel misbruik bij kinderen [Guideline for diagnostics of (suspicion of) sexual abuse of children]. Author.

- Oosterbaan, V., Covers, M. L. V., Bicanic, I. A. E., Huntjens, R. J. C., & de Jongh, A. (2019). Do early interventions prevent PTSD? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of early interventions after sexual assault. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1682932. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1682932

- Paras, M. L., Murad, M. H., Chen, L. P., Goranson, E. N., Sattler, A. L., Colbenson, K. M., Elamin, M. B., Seime, R. J., Prokop, L. J., & Zirakzadeh, A. (2009). Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association, 302(5), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1091

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu [RIVM]. (2020). Richtlijn Seksaccidenten 2020 [Guidelines sexual accidents 2020]. Author.

- Roberts, N. P., Kitchiner, N. J., Kenardy, J., Lewis, C. E., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Early psychological intervention following recent trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1695486. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1695486

- Rose, S. C., Bisson, J., Churchill, R., & Wessely, S. (2002). Psychological debriefing for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, 1465–1858. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000560

- Rothbaum, B. O., Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Murdock, T., & Walsh, W. (1992). A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(3), 445–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050309

- Steenkamp, M. M., Dickstein, B. D., Salters-Pedneault, K., Hofmann, S. G., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Trajectories of PTSD symptoms following sexual assault: Is resilience the modal outcome? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(4), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21718

- Vanoni, M., Kriek, F., & Lunneman, K. (2013). Meerwaarde integrale opvang en hulpverlening aan slachtoffers van seksueel geweld. Exploratief onderzoek naar de Centra Seksueel Geweld in Utrecht en Nijmegen. Regioplan Beleidsonderzoek in samenwerking met Verweij-Jonker.

- Verlinden, E., van Meijel, E. P., Opmeer, B. C., de Roos, C., Bicanic, I. A., Beer, R., Lamers-Winkelman, F., Olff, M., Boer, F., & Lindauer, R. J. (2014). Characteristics of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale in a clinically referred Dutch sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21910

- Vik, B. F., Nottestad, J. A., Schei, B., Rasmussen, K., & Hagemann, C. T. (2019). Psychosocial vulnerability among patients contacting a Norwegian sexual assault center. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(10), 2138–2157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516659657

- WHO (World Health Organisation). (2003). Guidelines for medio-legal care for victims of sexual violence. Author.