ABSTRACT

Background: Trauma exposure prevalence and consequent post-traumatic stress disorder among South African adolescents are significant. Sleep disturbances are among the most frequently reported difficulties faced by those dealing with PTSD. The current study examined the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention on PTSD symptom severity and sleep disturbance.

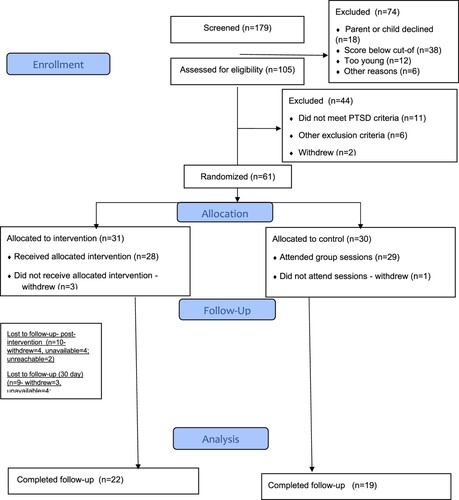

Method: Sixty-one adolescents with PTSD diagnoses and sleep disturbance were randomly assigned (1:1) to one individual and four group sessions of a sleep intervention (SAASI) or a control group. Participants completed the Child PTSD symptom scale for DSM5 (CPSS-5) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) among other sleep and psychiatric measures. The trial was registered on the Pan African Trial Registry (PACTR202208559723690).

Results: There was a significant but similar decrease in PSQI scores in both groups over time indicating no overall intervention effect (Wald test = −2.18, p = .029), mean slope = −0.2 (95% CI: −0.37 to −0.02) (p = .583). On the CPSS-5, interaction between groups was also not significant (p = .291). Despite this overall finding, the mean difference in CPSS-SR-5 scores increased over time, with the difference between groups post-treatment -9.10 (95%CI: −18.00 to −0.21), p = .045 and the 1-month follow-up contrast - 11.22 (95%CI: −22.43 to −0.03), p = .049 suggesting that PTSD symptom severity decreased more in the intervention group than the control group. The dropout rate was higher than expected for both the intervention (n = 10; 32%) and control (n = 8; 26.7%) groups. Dropout were mostly school commitments or travel related.

Conclusions: Early findings suggest a trend towards dual improvement in sleep quality and PTSD symptom severity in adolescents with a sleep disturbance and PTSD receiving a group sleep intervention (SAASI). Further investigation in a properly powered RCT with detailed retention planning is indicated.

HIGHLIGHTS

A four-week group sleep intervention seems feasible in adolescents with PTSD and sleep disturbances in a low-resource South African setting.

Utilising less specialised mental health resources such as nurses and counsellors in intervention delivery was feasible and effective.

Preliminary results are promising and support further research to establish the efficacy of the intervention.

Antecedentes: La prevalencia de la exposición al trauma y el consecuente trastorno de estrés post traumático entre los adolescentes sudafricanos son significativos. Los trastornos del sueño están entre las dificultades más frecuentemente reportadas por aquellos que lidian con el TEPT. El presente estudió examinó la viabilidad y eficacia de la intervención Grupal del sueño en Adolescentes Sudafricanos sobre la gravedad de los síntomas del TEPT y los trastornos del sueño.

Método: Sesenta y un adolescentes con diagnostico de TEPT y trastorno del sueño fueron asignados al azar (1:1) a una intervención individual y cuatro sesiones de intervención grupal del sueño para adolescentes (SAASI) o a un grupo control. Los participantes completaron la escala infantil de síntomas TEPT del DSM5 (CPSS-5, según sus siglas en ingles) y el índice de calidad de sueño de Pittsburgh (PSQI, según sus siglas en inglés) entre otras mediciones psiquiátricas. El ensayo se inscribió en el Registro de Ensayos Clínicos Panafricanos (PACTR202208559723690).

Resultados: Hubo una disminución significativa pero similar en las puntuaciones del PSQI de ambos grupos en el tiempo, indicando que no hay un efecto general en la intervención (Prueba de Wald = −2.18, p = .029), pendiente media = −0.2 (IC del 95%CI: –0.37 a –0.02) (p = .583). En la CPSS-5, la interacción entre los grupos tampoco fue significativa (p = .291). A pesar de estos hallazgos generales, la diferencia de medias en las puntuaciones de CPSS-SR-5 se incrementaron en el tiempo, con diferencia entre el grupo postratamiento –9.10 (IC del 95%: –18.00 a –0.21), p = .045, y el grupo con 1 mes de seguimiento –11.22 (IC del 95%: –22.43 a –0.03), p = .049, sugiriendo que la gravedad de los síntomas del TEPT disminuyeron más en el grupo de intervención que en el grupo control. La tasa de deserción fue mayor que lo esperado tanto en el grupo de intervención (n = 10; 32%) como en el grupo control (n = 8; 26.7%). Las principales razones de la deserción fueron relacionadas a compromisos escolares o de viajes.

Conclusiones: Los primeros hallazgos sugieren una tendencia hacia una mejora dual en la calidad del sueño y la gravedad de los síntomas del TEPT en adolescentes con trastornos del sueño y TEPT al recibir una intervención grupal sobre el sueño (SAASI). Se indica una investigación más exhaustiva en un ECA con un programa de retención detallado. Los primeros resultados sugieren una tendencia hacia una mejora dual en la calidad del sueño y la gravedad de los síntomas del TEPT en adolescentes con trastornos del sueño y TEPT que reciben una intervención grupal sobre el sueño (SAASI). Se indica investigación adicional en un ECA adecuadamente potenciado con una planificación detallada de retención.

1. Background

Trauma exposure is highly prevalent amongst South African adolescents, with reports showing that between 50 and 99% have experienced at least one traumatic event (Burton & Leoschut, Citation2013; Burton et al., Citation2015; Seedat et al., Citation2004a; Suliman et al., Citation2005). A UNICEF report highlighted that between 2011 and 2012, over 50,000 children were victims of reported violent crimes in South Africa (Viviers André (UNICEF), Citation2013). A more recent report indicated 42% of South African children have experienced violence; 35% have experienced physical violence and 35% sexual abuse; with a staggering 99% of children in some areas reporting having experienced or witnessed violence in their home, school and/or community (Richter et al., Citation2018).

Trauma exposure can have significant deleterious effects on both physical and mental health (Bellis et al., Citation2019; Brindle et al., Citation2018) and can lead to Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Rates of PTSD amongst South African adolescents have been reported to range between 8% to 22% (Burton & Leoschut, Citation2013; Seedat et al., Citation2004b; Suliman et al., Citation2005). PTSD is itself highly co-morbid with other disorders. One of the most frequently reported co-morbid problems are sleep disturbances (such as insomnia, nightmares and sleep-disordered breathing), which affect about 70% of the population with PTSD/post-traumatic stress symptomatology (Ahmadi et al., Citation2022; Stekl & Collen, Citation2022; Swift et al., Citation2022).

Despite trauma-focused psychological and pharmacological therapies being among the first-line treatments for PTSD in adults (Hamblen et al., Citation2019), research has shown that sleep disturbances often remain following these interventions (Belleville & Dubé-Frenette, Citation2015; Raskind et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Sleep disturbances may be a risk factor for later PTSD symptomatology (Koren et al., Citation2002; Van Liempt et al., Citation2013) and may be involved in the maintenance of PTSD symptoms (Belleville & Dubé-Frenette, Citation2015; Stekl & Collen, Citation2022; Swift et al., Citation2022; Van Liempt et al., Citation2013), which means they should be specifically targeted in interventions. Indeed, interventions targeting sleep disturbances have been found to reduce symptoms of PTSD in adults (Nakamura et al., Citation2011; Swift et al., Citation2022).

Adolescence, is already a developmental period often characterised by sleep disturbances due to pervasive social changes, such as less parental control, more access to stimulating social activities and alcohol and substance use (Scott et al., Citation2022). Sleep disturbances in adolescents may even be a cause of ‘vicious cycles of escalating vulnerability and increased risk’ (Harvey et al., Citation2016, p. 341). Additionally, sleep disturbances (such as increased sleep onset latency, nocturnal activity, and sleep fragmentation) are more prevalent in child and adolescent populations exposed to trauma, which may in turn impact learning, concentration and emotional health amongst others (de Zambotti et al., Citation2018; Kovachy et al., Citation2013).

Given that adolescence is a critical developmental period, interventions which promote mental health are important. However, a recent report from South Africa found that 65% of young people with mental health issues stated they did not seek help for the mental health issues they experienced (UNICEF, Citation2021). This reality, as well as the limited number of child and adolescent mental health specialists (CAMH) available in the public health sector requires innovative strategies to increase access to treatments within communities and near where people live. Employing a stepped care model, utilising task-shifting (i.e. a public health approach where specific skills are delegated to less specialised health workers) and administering brief interventions in group format can therefore improve access to care as well as reduce the cost of care (Galvin & Byansi, Citation2020).

The current study examines the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of delivering an adapted version of the youth version of the Transdiagnostic Sleep and Circadian Intervention (TranS-C-Youth), developed by Harvey (Harvey et al., Citation2016), to adolescents diagnosed with PTSD, in South Africa. A study of at-risk youth demonstrated superior efficacy of the Trans-C-Youth over prolonged exposure for adolescents (PE-A) in improving sleep and several health outcomes, with sleep but not health outcomes remaining improved at six months post-intervention (Dong et al., Citation2020; Harvey et al., Citation2018). In this study we use a shorter group intervention (Details available in supplementary material, Appendix 2), the South African Adolescence Sleep Intervention (SAASI), developed by one of the study authors (MM), and delivered by registered nurses and counsellors with a 4-year psychology degree. Should this shorter group sleep intervention have dual beneficial effects on sleep impairment and PTSD symptom severity, fewer adolescent patients with PTSD might require referral for more costly, specialised, individual trauma-focused interventions, such as prolonged exposure for adolescents (PE-A). This could pave the way for the implementation of a stepped care model in the treatment of PTSD in adolescents.

To the best of our knowledge, no study so far has examined the effects of either the TranS-C-Youth intervention or a group sleep intervention administered in a task-shifted way on symptoms of PTSD in adolescents. The primary aim of the current study was to assess the feasibility and potential efficacy of delivering SAASI to trauma exposed South African adolescents. Feasibility was evaluated by reporting the dropout rate and reasons for dropout, intervention protocol adherence by counsellors, reported adverse and serious adverse events, and treatment adherence by the participants. Preliminary efficacy was evaluated by examining the effects of SAASI on change in self-reported sleep quality and symptoms of PTSD in adolescents.

2. Method

2.1. Study design and participants

The study involved a pre-, mid-, post-test and 1-month follow-up (FU) randomised control design. Thirty-one participants were assigned to the intervention group and 30 participants to a control group. A two-step screening process was used to determine eligibility for inclusion in the study. First, adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years, who experienced at least one traumatic event, met criteria for PTSD or subclinical PTSD (based on the CPSS score of ≥ 21), and experienced sleeping disturbance (based on a PSQI score of ≥5), were invited to a clinical diagnostic interview to further determine eligibility. The second step in the screening process involved meeting criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD (full or sub-threshold) based on a clinical diagnostic interview (CDI). Adolescents with who had commenced pharmacotherapy and/or structured psychotherapy for PTSD in the last three months were excluded. Adolescents with a history of traumatic brain injury and those with a current (past six months) substance use disorder were also excluded.

2.2.1 Sample size

The rule of thumb for pilot studies is to include at least 12 participants per group (Julious, Citation2005). However, due to the higher expected dropout rate on account of strict treatment adherence criteria (i.e. participants permitted to miss one treatment session only over the course of the treatment), we recruited 30 participants per group (total of 60). We expected a 20% dropout rate.

2.2. Procedures

Participants were recruited by researchers from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FHMS), Stellenbosch University (SU), South Africa, from schools and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) through recruitment visits, phone calls, emails, and the distribution of pamphlets. Recruitment targeted adolescents from low-income areas and informal settlements in surrounding suburbs of the FHMS, SU in Parow, Cape Town, Western Cape. Referring organisations/individuals were asked to complete a short referral form reporting trauma exposure, current symptoms and duration of symptoms, as well as contact details of the potential participant and their parent or guardian.

Following referral, participants were screened for eligibility. Potentially eligible participants were invited for a pre-intervention visit where the Life Events Checklist 5 (Gray et al., Citation2004) was used to capture trauma exposure and identify the index trauma, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children and adolescents (Sheehan et al., Citation2010) was completed to confirm PTSD. Adolescents who met criteria, who provided assent/consent, and whose caregivers provided written consent were randomised on a 1:1 ratio, using a computer-generated randomisation schedule, to the SAASI group or the control group (N = 5 per group, increased to N = 8 per group for the last 2 intervention and control groups due to the high drop-out rate). Allocation was concealed from the clinicians who conducted the assessments. Enrolled participants were invited to return within one week for Visit 0, when all self-report measures were completed. Participants in the intervention group then met with the treatment provider who explained the use of the sleep diary (a tool to monitor daily sleep-related information, e.g. sleep and wake times, number of awakenings during the night, medications used), who assisted with setting goals for treatment and discussing the administrative details of the next four group sessions.

The pre-intervention (V0), post-intervention (V2) and 1-month post-treatment (V3) assessments were conducted by two independent evaluators masked to treatment condition. The independent evaluators were clinical psychologists experienced in research and diagnostic assessments. All study visits and assessments were conducted at the university. The assessment schedule is available in . The pilot trial was written up using CONSORT guidance with a checklist included in the supplementary material.

Table 1. Required measures/samples/intervention sessions at each visit for participants in the control and intervention group in the South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention (SAASI) pilot trial.

2.3. Ethical considerations

The Health Research Ethics Committee, FHMS, Stellenbosch University approved the study (Reference: N18/10/132) and trial was registered with the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry (PACTR202208559723690). Ethical approval for the study was also obtained from the Psychology Filter Ethics Committee at the University of Ulster, where one of the authors (CA) was based at the time. Participants received refreshments and were reimbursed for transport costs at each study visit. They also received airtime vouchers (€ 1,53) at each visit (in order to send sleep diaries to the study team daily). At study conclusion, participants received a shopping voucher (€ 10,20) to thank them for their time. Psychologists managed the referral of adolescents who required additional psychological support after the one-month follow-up assessment visit.

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Feasibility

This was assessed through recruitment (numbers; ease of recruitment) and retention (numbers completing study procedures); numbers attending assessment visits; reasons for discontinuation; adherence to study procedures (completion of measures; evaluation of treatment integrity) and reported adverse events.

2.4.2. Efficacy

2.4.2.1. Primary outcome measures

2.4.2.1.1 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI contains 19 self-rated questions and five questions rated by the bed partner or roommate if one is available (Buysse et al., Citation1989). Only the self-rated questions are incorporated in scoring. The scores are combined to form seven component scores which are then added to yield one global score with a range of 0–21. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality and a score of ≥5 was used to distinguish good sleepers from poor sleepers in this study. High internal consistency, test-retest reliability, sensitivity (89.6%) and specificity (86.5%) have been found. The PSQI has sound psychometric properties and has been administered successfully in South African samples (Rockwood et al., Citation2001).

2.4.2.1.2 Child PTSD Symptom Scale self-report version for DSM-5 (CPSS-5 SR)

The CPSS-5 SR was used to assess PTSD symptom severity during the study (Foa et al., Citation2018). The CPSS is a 27-item self-report measure related to the index trauma (which was identified during the pre-intervention assessment). Twenty items are used to assess frequency and severity of past month DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, using a 5-point Likert scale. Seven Likert-scale type items assess functional impairment related to the experience of the PTSD symptoms. The CPSS has shown excellent internal consistency, good test–retest reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity for interview and self-report versions of the scale (Foa et al., Citation2018), Sound psychometric properties also have been demonstrated in other youth populations (Hermosilla et al., Citation2021; Meyer et al., Citation2015; Serrano-Ibáñez et al., Citation2018).

2.4.3. Secondary outcome measures

Secondary measures included sleep measures; the Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (LeBourgeois et al., Citation2005), the Fear of Sleep Inventory (Huntley et al., Citation2014), and the Insomnia Severity Index (Morin et al., Citation2011). In addition, the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, a measure of anxiety (March et al., Citation1997), and the Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale-6, a measure of adolescent depression (LeBlanc et al., Citation2002), were included. Details of these measures can be accessed in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary material section.

2.5. Treatment providers

Three treatment providers, who had previously completed either a four-year psychology or nursing degree, volunteered for this study. They were compensated for travel costs and received a € 51 voucher after completing treatment provision.

2.5.1 Training and supervision

A clinical psychologist with extensive expertise in cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) for sleep disorders (MM), provided training (21 h) in the SAASI procedures to researchers and treatment providers at FHMS, SU. The training entailed lecture sessions, demonstration video clips and role-play of all treatment components. MM and a local South-African clinical psychologist (JR) with extensive experience in CBT, specialising in the treatment of adolescent PTSD and trained in the TransC-Y and SAASI interventions, provided continuous guidance and supervision to the treatment providers for the duration of the study. Initial supervision sessions were in person with JR and on-line with MM. Later supervision was online with both supervisors as a result of the increased skill levels of treatment providers.

2.6. Treatment

2.6.1 SAASI group intervention

The original TranS-C-Youth is based on the principles of three evidence-based sleep interventions: (1) Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I); (2) timed light exposure and planned and regular sleep schedules often used in interventions for Delayed sleep phase disorder; and (3) Interpersonal and Social Rhythms Therapy (IPSRT) (Harvey, Citation2016). SAASI retained the treatment modules present in the TranS-C-Youth protocol outlined by Harvey (Citation2016) and added a component on progressive muscle relaxation. The TranS-C-Youth was condensed to one individual session (20–30 min) and four group sessions (90 min) instead of six individual sessions. The treatment modules and treatment sessions included in SAASI can be found in . Core and cross-cutting modules were covered with all participants. The optional modules were included if one or more of the participants in a treatment group required this module. The typical outline of treatment sessions can be found in Appendix 2 in the supplementary material.

Table 2. Modules and treatment sessions of South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention (SAASI).

Treatment providers checked in on the sleep diaries of participants assigned to their group at every visit, problem solved any sleeping issues, adjusted sleep prescription (if needed) and reinforced completion of diaries. The indicators used to determine the sleep recommendation are available in the supplementary material in Appendix 3. The sleeping arrangements of every participant were considered as part of planning of the sleep prescription. When participants were sharing rooms and beds treatment providers tried to find a sleep prescription that adhered to the treatment protocol.

2.6.2 Control group

The first session was an individual session and entailed training participants to complete daily sleep diaries. The control group met weekly, with a research assistant, for the next four weeks and submitted their sleep diaries at each visit.

2.6.3 Treatment Integrity

All treatment sessions were audio recorded with the permission of participants and, when required, from a guardian. Treatment provider adherence to the treatment protocol was reviewed by supervisors (JR & MM) during weekly supervision sessions. Treatment providers were equipped with detailed treatment manuals to use during sessions and role-played the next treatment session during group supervision in the week prior to delivery of that session. Participants’ sleep diaries and sleep prescriptions were reviewed weekly by supervisors, and any adjustment to the sleep prescription was integrated at the next treatment session. Group supervision had the added advantage of all treatment providers benefitting from the supervision as well as the experiences of their peer providers.

2.6.4 Discontinuation and adverse events

Participants were free to discontinue participation. Requests to discontinue treatment were discussed and referral for alternative treatment was provided. Every attempt was made to have a final interview with participants who discontinued treatment. A clinically significant deterioration in mental health was considered an adverse event. Any event requiring hospitalisation was considered a serious adverse event.

2.7. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were tabulated by group, using means, standard deviations, and percentages.

Sleep (PSQI) and PTSD (CPSS-5 SR) data, pre-, during- and post-intervention, were assessed within and between participant groups. Secondary measures were also subjected to within- and between-group analysis. The analysis was an intent-to-treat. To account for the missing data due to the high dropout rate and some missing items on self-report scales, imputation was based on full maximum likelihood estimation in linear mixed-effects regression models.

Linear mixed effects regression was used for the continuous outcomes to model the mean response on the fixed effects of time and intervention (group). A random effect for participants was used with time as a factor. The formal test for an intervention effect was the significance test for the interaction between time (week) and group. The baseline measurement was included as part of the four repeated measures for each participant. Since the baseline dataset had very little missing data, including the baseline time point facilitated a modified intention to treat analysis (i.e. including all participants with at least a baseline measurement).

For variables where there was a significant difference in mean profile of the groups over time, time-specific contrasts (estimated mean differences) between intervention and control groups were estimated. In the same way within-group-specific contrasts across the different time points were estimated and reported with 95% confidence intervals. Baseline scores were used as a covariant in the linear mixed effects regression analyses.

3. Results

provides a summary of participant flow in the South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention pilot trial (SAASI).

3.1. Feasibility

One hundred and seventy-nine adolescents volunteered to participate in the study. Of these, 61 participants who met criteria for full PTSD (no participant with a sub-threshold PTSD diagnosis met all inclusion criteria) and a sleep disturbance were randomised: 31 participants to the intervention group of which 21 completed treatment and attended one follow-up assessment; and 30 participants to the control group of which 23 attended all group sessions, and 20 attended one follow-up assessment ().

Table 3. Demographic and trauma exposure information for the intervention and control group in the South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention (SAASI) pilot trial.

Treatment adherence to the protocol was monitored by the two supervisors (MM and JR) at weekly group supervision sessions with treatment providers. Adherence to the treatment protocol appeared excellent based on confirming adherence to key treatment components during supervision. Supervisors confirmed that treatment providers followed the agenda of each session as presented in the outline of treatment () and covered the key concepts subsumed under these headings, as detailed in the treatment manual each treatment provider had received. Sleep diaries of participants and sleep prescriptions of treatment providers were reviewed and changes to the sleep prescription were advised when indicated. These changes would then be integrated into the sleep prescription based on the sleep diaries provided by participants at their next treatment session.

Given the LIMIC setting of these participants their living and sleeping arrangements could be challenging. Homes had an average of 5 (SD: 2.44; min: 1, max: 11) rooms of which 2 (SD: 1.221; min: 0, max: 5) were bedrooms. Almost two-thirds of participants indicated that they have a room or bed partner – with 18 (29.5%) indicating that they sleep with another individual in the same bed and 20 (32.8%) that they share a room. We did not record information on who the room/bed partner was, we did however discuss the participants expected sleeping arrangements in detail during training and at supervision sessions. We would implement the recommendations present within the treatment protocols as applicable to the unique circumstances of each participant. Situations such as sharing a bed or not having an alternative room or place to sit when awake at night, when the rest of the house have settled down, were discussed. Appropriate adjustments that were aligned with the treatment protocol would be made, e.g. sitting on the edge of the bed, or sitting on the floor with a pillow when being awake during the night. Participants living circumstances did not, according to feedback during supervision, lead to deviations from the central principles of the treatment guidelines.

The dropout rate was higher than expected for both the intervention (n = 10; 32%) and control (n = 8; 26.7%) groups. Three participants who were randomised dropped out of the SAASI group, prior to commencing treatment. One participant randomised to the control group also dropped out prior to the first contact session. Due to the short duration of the intervention (1 individual and 4 group sessions) participants missing more than one session were not permitted to continue. Seven participants in the SAASI intervention group missed more than one session. Reasons provided for dropout were mostly school or travel related. Participants did not report difficulty in tolerating the intervention as the reason for missing sessions. Six adolescents in the control group also missed more than one session and had to be withdrawn. They had similar reasons for missing sessions, namely school/after-school commitments or transport difficulties. In both groups, difficulties with contacting participants when not at school also resulted in missed sessions/assessments.

Completion of the weekly sleep diaries proved to be a challenge for participants. While most completed their sleep diaries, this was not done daily, and counsellors had to continually motivate and address non-completion of sleep diaries throughout the treatment period.

Four participants were referred for treatment for ongoing symptomatology (n = 3) or suicide ideation (n = 1) at the end of the intervention period. No adverse or serious adverse events were reported during the study period.

3.2. Efficacy outcomes

3.2.1 Participant baseline sleep characteristics

On the PSQI mean bed time was reported to be 18h34 (SD: 8.05, min: 1h00, max: 24h55) and wake-up time 07h01 (SD: 2.06, min: 02h00, max: 13h00). With regard to sleep duration, only 24 (39.3%) slept for >7 h a night, N = 8 (13.1%) slept between 6 and 7 h, N = 6 (9.8%) for 5–6 h and N = 14 (23%) for less than 5 h a night. Sleep efficiency was >85% in the majority (N = 36, 59%), 75%−84% in N = 3 (4.9%), 65–74% in N = 1 (1.6%) and under 65% in N = 12 (19.7%).

displays baseline characteristics reported on the ISI.

Table 4. Baseline Sleep Characteristics – ISI.

Due to the dropout rate, we compared baseline characteristics of participants (Supplementary material Appendix 4) who returned for follow-up assessments with those who did not. The only variable that significantly differed between groups was the PSQI (F(1,49) = 5.069, p = .029). The group that did not return for assessments scored significantly lower on baseline sleep quality (although the scores were still indicative of a sleep disturbance).

3.2.2 Primary measures

shows the primary outcome data.

Table 5. Between-group outcome data for primary measures in the South African Adolescence Group Sleep Intervention (SAASI) pilot trial.

3.2.2.1 Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

There was a significant decrease in PSQI scores in both groups over time (Wald test = −2.18, p = .029), mean slope = −0.2 (95%CI: –0.37 to –0.02). This downward trend was similar (parallel) across time (p = .583) and this indicates no overall intervention effect. At baseline, the SAASI intervention group had a significantly lower mean PSQI score as compared to the control group (mean = 9.96; SD = 2.73 vs. mean = 11.81; SD = 2.65; mean difference –1.9; (95%CI: –3.3 to –0.6); p = .006).

3.2.2.2 Child PTSD Symptom Scale self-report version for DSM-5 (CPSS-SR-5)

The mean difference in baseline scores between the intervention and control group was –5.90 (95%CI: –14.13–2.32), p = .159, and did not differ significantly. The interaction between groups was not significant (p = .291) and hence the mean CPSS profiles are parallel and do not differ significantly overall. Despite this overall finding, mean CPSS difference increased slightly over time with the contrast post-intervention being –9.10 (95%CI: –18.00 to –0.21), p = .045 and the 1-month follow-up contrast being –11.22 (95%CI: –22.43 to –0.03), p = .049.

3.2.2.3 Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID)

All participants met criteria for PTSD on the MINI-Kid at baseline. Post-intervention, significantly fewer participants in the intervention than the control arm still met PTSD criteria (16.7% vs 55%; p = .011). At the 1-month follow-ups, 22.7% of participants in the intervention arm and 50% in the control arm met PTSD criteria (p = .092).

At baseline the intervention group had an average of 3.71 (1.95) disorders based on the MINI-Kid. This reduced to 1.96 (1.97) post-intervention and 2.18 (1.71) at the 1-month post-intervention follow-up. The control group had an average of 3 (1.89) disorders which reduced to 2.55 (2.16) and 2.21 (1.48) at post and 1-month follow-ups. Differences between intervention and control groups were not significant (p > .05).

3.3. Secondary measures

The between group and within group results for all secondary measures can be accessed in Appendices 5, 6 and 7 of the supplementary material. A significant intervention effect between groups was present for two secondary measures, namely the FoSI (p = .03) and KADS-6 (p = .007). The SAASI intervention group experienced significantly greater reductions in fear to sleep (FoSI) and in depression symptoms (KADS-6) than the control group.

4. Discussion

The primary aims of the study were to assess the preliminary efficacy and to examine the feasibility of the SAASI group intervention in South African adolescents. SAASI was not superior to control in improving sleep quality (as measured by the PSQI) or in reducing PTSD symptoms (as measured by the CPSS-5 SR). However, even though there was not a significant intervention effect on the primary sleep measure, there was an improvement in sleep quality in both intervention and control groups, this improvement was sustained until 1-month post-treatment in the intervention group but not in the control group. This may point to a longer-term impact which translates into a lower likelihood for these adolescents to show sleep disruption over time and to the associated negative impacts thereof. The improvement in PTSD symptoms was also greater in the intervention group at both post-treatment and 1-month follow-ups and reduced to a score of below 30, which is typically indicative of the absence of a PTSD diagnosis. Only 16.7% of the intervention group still met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis at post-assessment (p = .011) and only 22.7% met criteria at 1-month FU (p = .092), in comparison to the control group that had 55% (post-intervention FU) and 50% (1-month FU) of participants still meeting criteria. We acknowledge the underpowered nature of these pilot analyses. Nonetheless, these findings add to the limited empiric evidence supporting integrated psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD and sleep disturbances.

Each participants specific sleeping arrangements were taken into consideration in planning the sleep prescription that was provided to each participant. When participants shared a bed, it was typically with a sibling that was also of school-going age. They typically had to wake at the same time as they would use the same transport to travel to school. The changes to the sleep routine of the participant therefore mostly centred around moving bedtime earlier, dealing with early awakening, dealing with snoozing, or if multiple longer (more than 15 min. per awakening) awakenings occurred leaving the room or engaging in an activity while sitting on the side of the bed or the floor (if no other space was available) and therefore reducing time in bed. Sleep restriction was also implemented when required. Participants in this study did not report this to cause a disruption to people sharing the room.

A factor possibly influencing outcomes was the weekly meetings and weekly completion of sleep diaries by control participants. The effect of meetings, attention from the research assistant and the increased awareness associated with monitoring one’s sleep might account for some of the improvement seen in the control group, characterised as the Hawthorne effect (Diaper, Citation1990). Therefore, even the limited focus on sleep (completing the sleep diary) seems to contribute to a trend of improvement in sleep and supports that an intervention focussing on sleep will be helpful. Additionally, as many participants came from the same schools, there may have been some degree of information sharing. The results do however suggest, based on the improvement over time in the intervention group, that significant intervention effects may be possible in an adequately powered group intervention study. We are further encouraged by findings that group-based psychotherapeutic treatment significantly improved sleep in a residential PTSD treatment programme (albeit in veterans) (DeViva et al., Citation2018). In the follow-up RCT that is in progress, supervision and completion monitoring of self-report measures are in place. The dropout rate can also be improved on by better communication with both participants and coordinators at the schools, as well as arranging transport for participants. Future trials may wish to explore the use of studies within a trial (SWAT) to explore ways to improve recruitment and retention (Treweek et al., Citation2018).

On secondary outcomes, there was a significant reduction experienced in the Fear of Sleep Inventory (FOSI) in the intervention group compared to the control group. This finding suggests that a sleep intervention can lead to a reduction in fear of sleeping in those affected with PTSD. Similar results were obtained in two studies of adults with PTSD and insomnia, in which CBT-I lead to significant improvements in hyperarousal symptoms and fear of sleep (Gupta & Sheridan, Citation2018; Kanady et al., Citation2018). This is a significant finding as fear of sleep may account for some of the variance in the relationship between trauma and sleep difficulties (Pruiksma et al., Citation2014) since fear of sleep may play a role in maintaining trauma-related sleep disturbances over time (Werner et al., Citation2021). This finding is of particular interest in our setting, where participants are likely to live in high crime areas leading to a continuous state of stress. Since reactions to environmental stress can have an adverse impact on autonomic arousal during sleep, a reduction in the fear of sleep may lead to improved sleep and as a result, may have wider benefits that extend to physical health (Mellman et al., Citation2018).

The secondary finding that the SAASI intervention group experienced a significantly better improvement in depression severity (KADS) is also encouraging and possibly points to the importance of improvement in sleep duration and quality in adolescents linking to improvements in mood symptoms (Roberts & Duong, Citation2014; Stheneur et al., Citation2019). The link between improvement in PTSD symptoms and depression is well-documented and early intervention to improve outcomes in youth would be beneficial (Xian-Yu et al., Citation2022).

Regarding feasibility, although the study was well-received by schools and organisations we recruited from, due to overburdened staff, we did not receive many referrals. Recruitment drives, where we visited schools and spoke to learners about trauma and its consequences, and conducted screenings, worked well. Attrition rates were high and was negatively impacted by school holidays, when participants were less likely to attend intervention sessions or study assessments, and by study participants not attending school during the term, which also resulted in several missed intervention sessions and assessments. To combat this, we intend to run groups only during the school term for the RCT. Additionally, transport difficulties led to missed sessions. To address this, we arranged for a driver to pick-up and drop-off participants and will continue with this arrangement.

Reviews have highlighted the challenges of retaining patients and participants in trauma-related sleep treatments/ research, and suggest that protocol adaptations may be required to optimise treatment delivery (Koffel et al., Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2020). Mobile-based interventions have been found to be effective in the delivery of CBT-I for instance (Wei et al., Citation2024). However, barriers to access remain. A recent study in rural South African youth identified some of these as the high cost of data, restrictive religious beliefs, limited privacy, lack of native languages on most digital platforms, low digital literacy, and complicated user interface, leading to the low uptake of digital mental health apps among the young people in their study (Mindu et al., Citation2023).

Completion of the weekly sleep diaries proved to be a challenge for participants. While most completed their sleep diaries, this was not completed daily, and counsellors had to continually motivate and address the non-completion of sleep diaries throughout the treatment period. The degree of missing data resulting from incomplete self-report measures was unfortunate. Incomplete self-report measures will be managed in the upcoming RCT by having a research assistant provide individual support during the completion of measures and checking that all items on questionnaires and all questionnaires have been answered.

Despite these challenges, we believe that the measures that have been put in place and those we intend to put in place for the RCT proper make this a feasible intervention. Furthermore, the shorter group format makes the intervention time, human resource and cost (e.g. in terms of transport) feasible. Early indications of intervention effects on both the primary outcomes of sleep and PTSD severity are encouraging.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study are the inclusion of a control group rather than only pre- and post-assessments, assessment of PTSD by both self-report and clinicians at pre- and post-intervention and follow up at 1-month post-intervention. Limiting of confounders by strictly enforced inclusion/exclusion criteria is also a strength.

Limitations include missing data and high dropout rates. For instance, only 26 participants in each group either completed or did not have missing data in the PSQI at baseline. Future studies could consider electronic data capturing that does not permit skipping of items. We did not control for time and duration of trauma exposure, or specify whether trauma was complex, which may have influenced PTSD symptom severity. Further, we did not assess physical health status, which can influence sleep, although participants with lasting medical/mental illness and/or a history of traumatic brain injury were excluded. We also did not have an objective measure of sleep. Future studies should consider how best to incorporate this, e.g. use of actigraphy watches.

4.2. Implications

In conclusion, early findings are suggestive that SAASI may lead to a dual improvement – on both sleep quality and PTSD symptom severity. Further investigation in a properly powered RCT is thus indicated.

Apendix 7 consort checklist.doc

Download MS Word (217.5 KB)Suplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (59.5 KB)Suplementary Material R1_edited.docx

Download MS Word (66.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jaco Rossouw, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmadi, R., Rahimi, S., Olfati, M., Javaheripour, N., Emamian, F., Ghadami, M. R., … Sepehry, A. A. (2022). Insomnia and post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis on interrelated association (n = 57,618) and prevalence (n = 573,665) (n = 57,618) and prevalence (n = 573,665). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 141, 104850. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2022.104850

- Belleville, G., & Dubé-Frenette, M. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and nightmares in PTSD. In: C. Martin, V. Preedy, & V. Patel (Eds.), Comprehensive guide to post-traumatic stress disorder. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08613-2_38-1

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Ramos Rodriguez, G., Sethi, D., & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(10), e517–e528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

- Brindle, R. C., Cribbet, M. R., Samuelsson, L. B., Gao, C., Frank, E., Krafty, R. T., … Hall, M. H. (2018). The relationship between childhood trauma and poor sleep health in adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80(2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000542

- Burton, P., & Leoschut, L. (2013). School violence in South Africa: Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study (2013) | Children’s Institute. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/violence-schools/monographs/school-violence-in-SA-results-of-the-2012-national-school-violence-study.

- Burton, P., Ward, C., Artz, L., & Leoschut, L. (2015). The Optimus Study on child abuse, violence and neglect in South Africa (2015) | Children’s Institute. http://www.ci.uct.ac.za/overview-violence/research-bulletin/optimus-study-on-child-abuse-violence-neglect-in-SA.

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

- de Zambotti, M., Goldstone, A., Colrain, I. M., & Baker, F. C. (2018). Insomnia disorder in adolescence: Diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 39, 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.009

- DeViva, J. C., McCarthy, E., Bieu, R. K., Santoro, G. M., Rinaldi, A., Gehrman, P., & Kulas, J. (2018). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia delivered to veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving residential treatment is associated with improvements in sleep independent of changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Traumatology, 24(4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000152

- Diaper, G. (1990). The Hawthorne effect: A fresh examination. Educational Studies, 16(3), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569900160305

- Dong, L., Dolsen, M. R., Martinez, A. J., Notsu, H., & Harvey, A. G. (2020). A transdiagnostic sleep and circadian intervention for adolescents: Six-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(6), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13154

- Foa, E. B., Asnaani, A., Zang, Y., Capaldi, S., & Yeh, R. (2018). Psychometrics of the child PTSD symptom scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1350962

- Galvin, M., & Byansi, W. (2020). A systematic review of task shifting for mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Mental Health, 49(4), 336–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2020.1798720

- Gray, M. J., Litz, B. T., Hsu, J. L., & Lombardo, T. W. (2004). Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment, 11(4), 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104269954

- Gupta, M. A., & Sheridan, A. D. (2018). Fear of sleep may be a core symptom of sympathetic activation and the drive for vigilance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(12), 2093. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.7550

- Hamblen, J. L., Norman, S. B., Sonis, J. H., Phelps, A. J., Bisson, J. I., Nunes, V. D., … Schnurr, P. P. (2019). A guide to guidelines for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: An update. Psychotherapy, 56(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000231

- Harvey, A. G., Hein, K., Dolsen, M. R., Dong, L., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Gumport, N. B., … Blum, D. J. (2018). Modifying the impact of eveningness chronotype (“night-owls”) in youth: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(10), 742–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.04.020

- Harvey, A. G., Hein, K., Dong, L., Smith, F. L., Lisman, M., Yu, S., … Buysse, D. J. (2016). A transdiagnostic sleep and circadian treatment to improve severe mental illness outcomes in a community setting: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 17(1)), https://doi.org/10.1186/S13063-016-1690-9

- Hermosilla, S., Forthal, S., Van Husen, M., Metzler, J., Ghimire, D., & Ager, A. (2021). The child PTSD symptom scale: Psychometric properties among earthquake survivors. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(6), 1184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01097-z

- Huntley, E. D., Hall Brown, T. S., Kobayashi, I., & Mellman, T. A. (2014). Validation of the fear of sleep inventory (FOSI) in an urban young adult African American sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21882

- Julious, S. A. (2005). Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceutical Statistics, 4(4), 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.185

- Kanady, J. C., Talbot, L. S., Maguen, S., Straus, L. D., Richards, A., Ruoff, L., … Neylan, T. C. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia reduces fear of sleep in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 14(7), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.7224

- Koffel, E., Bramoweth, A. D., & Ulmer, C. S. (2018). Increasing access to and utilization of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I): A narrative review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(6), 955–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4390-1

- Koren, D., Arnon, I., Lavie, P., & Klein, E. (2002). Sleep complaints as early predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder: A 1-year prospective study of injured survivors of motor vehicle accidents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 855–857.

- Kovachy, B., O’Hara, R., Hawkins, N., Gershon, A., Primeau, M. M., Madej, J., & Carrion, V. (2013). Sleep disturbance in pediatric PTSD: Current findings and future directions. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 09(5), 501. https://doi.org/10.5664/JCSM.2678

- LeBlanc, J. C., Almudevar, A., Brooks, S. J., & Kutcher, S. (2002). Screening for adolescent depression: Comparison of the Kutcher adolescent depression scale with the Beck depression inventory. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 12(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1089/104454602760219153

- LeBourgeois, M. K., Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Wolfson, A. R., & Harsh, J. (2005). The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics, 115(Supplement_1), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0815H

- March, J. S., Parker, J. D. A., Sullivan, K., Stallings, P., & Conners, C. K. (1997). The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019

- Mellman, T. A., Bell, K. A., Abu-Bader, S. H., & Kobayashi, I. (2018). Neighborhood stress and autonomic nervous system activity during sleep. Sleep, 41, 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1093/SLEEP/ZSY059

- Meyer, R. M. L., Gold, J. I., Beas, V. N., Young, C. M., & Kassam-Adams, N. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of the child PTSD symptom scale in Spanish and English. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0482-2

- Miller, K. E., Brownlow, J. A., & Gehrman, P. R. (2020). Sleep in PTSD: Treatment approaches and outcomes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 34, 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.017

- Mindu, T., Mutero, I. T., Ngcobo, W. B., Musesengwa, R., & Chimbari, M. J. (2023). Digital mental health interventions for young people in rural South Africa: Prospects and challenges for implementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH20021453

- Morin, C. M., Belleville, G., Bélanger, L., & Ivers, H. (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 34(5), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.601

- Nakamura, Y., Lipschitz, D. L., Landward, R., Kuhn, R., & West, G. (2011). Two sessions of sleep-focused mind-body bridging improve self-reported symptoms of sleep and PTSD in veterans: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70(4), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.007

- Pruiksma, K. E., Taylor, D. J., Ruggero, C., Boals, A., Davis, J. L., Cranston, C., … Zayfert, C. (2014). A psychometric study of the fear of sleep inventory-short form (FoSI-SF). Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 10(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3710

- Raskind, M. A., Peskind, E. R., Chow, B., Harris, C., Davis-Karim, A., Holmes, H. A., … Huang, G. D. (2018). Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(6), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507598

- Richter, L. M., Mathews, S., Kagura, J., & Nonterah, E. (2018). A longitudinal perspective on violence in the lives of South African children from the Birth to Twenty Plus cohort study in Johannesburg-Soweto. South African Medical Journal, 108(3), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12661

- Roberts, R. E., & Duong, H. T. (2014). The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep, 37(2), 239. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.3388

- Rockwood, K., Mintzer, J., Truyen, L., Wessel, T., & Wilkinson, D. (2001). Effects of a flexible galantamine dose in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomised, controlled trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 71(5), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.71.5.589

- Scott, A. J., Webb, T. L, Martyn-St James, M., Rowse, G., & Weich, S. (2022). Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101556

- Seedat, S., Nyamai, C., Njenga, F., Vythilingum, B., & Stein, D. J. (2004). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress symptoms in urban African schools. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(FEB), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1192/BJP.184.2.169

- Serrano-Ibáñez, E. R., Ruiz-Párraga, G. T., Esteve, R., Ramírez-Maestre, C., & López-Martínez, A. E. (2018). Validation of the child PTSD symptom scale (CPSS) in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema, 30(1), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.7334/PSICOTHEMA2017.144

- Sheehan, D. V., Sheehan, K. H., Shytle, R. D., Janavs, J., Bannon, Y., Rogers, J. E., … Wilkinson, B. (2010). Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(3), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi

- Stekl, E. K., & Collen, J. F. (2022). Commentary No time to waste! Acute sleep interventions after trauma. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 18(9), 2091–2092. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.10204

- Stheneur, C., Sznajder, M., Spiry, C., Marcu Marin, M., Ghout, I., Samb, P., & Benoist, G. (2019). Sleep duration, quality of life and depression in adolescents: A school-based survey. Minerva Pediatrica, 71(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4946.17.04818-6

- Suliman, S., Kaminer, D., & Seedat, S. (2005a). Assessment techniques and South African community studies of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 17(2), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280580509486601

- Suliman, S., Kaminer, D., Seedat, S., & Stein, D. J. (2005b). Assessing post-traumatic stress disorder in South African adolescents: Using the child and adolescent trauma survey (CATS) as a screening tool. Annals of General Psychiatry, 4(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-4-2

- Swift, K. M., Thomas, C. L., Balkin, T. J., Lowery-Gionta, E. G., & Matson, L. M. (2022). Acute sleep interventions as an avenue for treatment of trauma-associated disorders. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 18(9), 2291–2312. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.10074

- Treweek, S., Bevan, S., Bower, P., Campbell, M., Christie, J., Clarke, M., … Williamson, P. R. (2018). Minimally invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy (LEOPARD-2): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 19(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2423-4

- UNICEF. (2021). 65 per cent of young people with mental health related issues did not seek help – UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/press-releases/65-cent-young-people-mental-health-related-issues-did-not-seek-help-unicef.

- Van Liempt, S., Van Zuiden, M., Westenberg, H., Super, A., & Vermetten, E. (2013). Impact of impaired sleep on the development of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Depression and Anxiety, 30(5), 469–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22054

- Viviers André (UNICEF). (2013). The study on special summary for teens violence against children in South Africa. www.unicef.org/southafrica.

- Wei, J., Xu, Y., & Mao, H. (2024). Discovering biomarkers associated and predicting cardiovascular disease with high accuracy using a novel nexus of machine learning techniques for precision medicine. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50600-8

- Werner, G. G., Riemann, D., & Ehring, T. (2021). Fear of sleep and trauma-induced insomnia: A review and conceptual model. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 55, 101383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101383

- Xian-Yu, C. Y., Deng, N. J., Zhang, J., Li, H. Y., Gao, T. Y., Zhang, C., & Gong, Q. Q. (2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder: Meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 502–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.111

- Zhang, Y., Ren, R., Vitiello, M. V., Yang, L., Zhang, H., Shi, Y., … Tang, X. (2022). Efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapeutic and pharmacological interventions for trauma-related nightmares: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104717