ABSTRACT

Background: Preliminary evidence provides support for the proposition that there is a dissociative subtype of Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Research on this proposition would extend our knowledge on the association between CPTSD and dissociation, guide contemporary thinking regarding placement of dissociation in the nosology of CPTSD, and inform clinically useful assessment and intervention.

Objectives: The present study aimed to investigate the co-occurring patterns of CPTSD and dissociative symptoms in a large sample of trauma exposed adolescents from China, and specify clinical features covariates of such patterns including childhood trauma, comorbidities with major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and functional impairment.

Methods: Participants included 57,984 high school students exposed to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. CPTSD and dissociative symptoms, childhood traumatic experience, and functional impairment were measured with the Global Psychotrauma Screen for Teenagers (GPS-T). Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) symptoms were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), respectively. Latent class analysis (LCA) was employed to test the co-occurring patterns of CPTSD and dissociative symptoms. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and chi-square tests were respectively used to examine between-class differences in continuous and categorical clinical covariates.

Results: A 5-class model emerged as the best-fitting model, including resilience, predominantly PTSD symptoms, predominantly disturbances in self-organization (DSO)symptoms, predominantly CPTSD symptoms, and CPTSD dissociative subtype classes. The CPTSD dissociative subtype class showed the lowest level of functioning and the highest rates of MDD, GAD and childhood trauma.

Conclusions: Our findings provide initial empirical evidence supporting the existence of a dissociative subtype of CPTSD, and inform for further research and clinical practice on traumatized individuals.

HIGHLIGHTS

The present study identified a dissociative subtype of ICD-11 CPTSD among trauma exposed youth.

The dissociative subtype of ICD-11 CPTSD was associated with poorer mental health outcomes.

Findings of this study provide initial empirical evidence supporting the existence of a dissociative subtype of CPTSD.

Antecedentes: Las pruebas preliminares apoyan la propuesta de que existe un subtipo disociativo del trastorno de estrés postraumático complejo (TEPTC). La investigación sobre esta propuesta ampliaría nuestro conocimiento sobre la asociación entre el TEPTC y la disociación, guiaría el pensamiento contemporáneo con respecto a la ubicación de la disociación en la nosología del TEPTC e informaría sobre evaluaciones e intervenciones clínicamente útiles.

Objetivos: El presente estudio tuvo como objetivo investigar los patrones concurrentes de TEPTC y síntomas disociativos en una gran muestra de adolescentes de China expuestos a traumas, y especificar las características clínicas covariables de tales patrones, incluyendo trauma infantil, comorbilidades con trastorno depresivo mayor (EDM) y trastorno de ansiedad generalizada (TAG) y deterioro funcional.

Métodos: Los participantes incluyeron 57.984 estudiantes de secundaria expuestos a la pandemia de la enfermedad por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). El TEPTC y los síntomas disociativos, la experiencia traumática infantil y el deterioro funcional se midieron con el Mapeo Global Psicotrauma para Adolescentes (GPS-T por sus siglas en ingles). Los síntomas del trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) y del trastorno de ansiedad generalizada (TAG) se midieron con el Cuestionario de Salud del Paciente-9 (PHQ-9) y el Trastorno de Ansiedad Generalizada-7 (GAD-7), respectivamente. Se empleó el análisis de clases latentes (ACL) para analizar los patrones concurrentes del TEPT y los síntomas disociativos. Se utilizaron análisis de covarianza (ANCOVA) y las pruebas de chi-cuadrado respectivamente para examinar las diferencias entre clases en covariables clínicas continuas y categóricas.

Resultados: Un modelo de 5 clases emergió como el modelo que mejor se ajustaba, incluyendo las clases de resiliencia, síntomas predominantemente de TEPT, síntomas predominantemente de alteraciones en la autoorganización (DSO), síntomas predominantemente de TEPTC y subtipo disociativo de TEPTC. La clase del subtipo disociativo del TEPTC mostró el nivel más bajo de funcionamiento y las tasas más elevadas de TDM, TAG y trauma infantil.

Conclusiones: Nuestros hallazgos proporcionan evidencia empírica inicial que apoya la existencia de un subtipo disociativo de TEPTC e informan para futuras investigaciones y prácticas clínicas en individuos traumatizados.

1. Introduction

In the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, Citation2018), complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is formally defined as a mental disorder in a new category of psychopathology, namely ‘Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress’. Symptom criteria of CPTSD include three symptom clusters shared with PTSD (i.e. re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal), and three additional symptom clusters reflecting disturbances in self-organization (DSO) (i.e. affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbances in relationships). The construct validity of ICD-11 CPTSD has been well-supported (Brewin et al., Citation2017; Redican et al., Citation2021). Epidemiological studies using representative samples from general populations reported the prevalence of CPTSD ranging from 1% to 8% which is comparable with ICD-11 PTSD (Maercker et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, a number of studies also revealed that relative to PTSD, CPTSD was associated with more severe functional impairment and poor mental health outcomes (Cloitre, Citation2020; Maercker et al., Citation2022). Considering CPTSD as a newly recognized psychiatric condition, further research on its correlates and features is clearly needed.

Dissociation has been identified as an important aspect of psychological responses to traumatic stress for a long time (Dalenberg et al., Citation2012). According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), dissociation involves failures in the normal integration of individuals’ biopsychosocial experiences including consciousness, motor control and perception, memory, emotion, and identity, etc. Based on empirical evidence summarized by a comprehensive and systematic review (Carlson et al., Citation2012), Dalenberg and Carlson (Citation2012) evaluated six theoretical models about the relationships among traumatic stress, dissociation, and DSM-IV PTSD, and concluded that the component model (i.e. dissociation as a component of PTSD) and subtype model (i.e. dissociation as a subtype of PTSD) received the strongest support. Subsequently, the DSM-5 officially defined a dissociative subtype of PTSD characterized by symptoms of depersonalization or derealization in addition to PTSD. Construct validity of the dissociative subtype of PTSD has been demonstrated by a large number of studies (Hansen et al., Citation2017; Misitano et al., Citationin press), and a recent meta-analysis reported that the estimated prevalence of the dissociative subtype was about 38.1% among individuals with PTSD (White et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, various studies also revealed that compared with non-dissociative PTSD, the dissociative subtype exhibited distinguishable clinical and neurobiological features (van Huijstee & Vermetten, Citation2018), suggesting that the two conditions require different types of interventions.

ICD-11 CPTSD also strongly links to dissociation. First, in the predecessors of CPTSD such as complex PTSD (Herman, Citation1992) and Disorders of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified (DESNOS) in the appendix of DSM-IV, dissociation was recognized as a core feature. Second, CPTSD and dissociation share common etiological risk factors. According to previous meta-analyses (Leiva-Bianchi et al., Citation2023; Vonderlin et al., Citation2018), childhood abuse and neglect were identified as primary risk factors for both CPTSD and dissociation. Third, the close association between CPTSD and dissociation has been demonstrated in a number of empirical studies. It was reported that individuals with CPTSD experienced significantly higher levels of dissociative symptoms relative to those without CPTSD, and CPTSD symptoms were positively correlated with dissociative symptoms (Fung et al., Citation2023; Hamer et al., Citation2024). Considering the strong relationship between CPTSD and dissociation, there is also an ongoing discussion about whether CPTSD is dissociative in nature (Hamer et al., Citation2024). It should be noted that only a sub-group of individuals with CPTSD (ranging from 28.6–76.9%) may experience clinically significant dissociative symptoms (Fung et al., Citation2023). Hyland and colleagues (Citation2024) adopted latent class analysis (LCA) to further investigate whether CPTSD symptoms could occur independently of dissociation using data from a nationally representative adult sample. In this study, a four-class solution was identified as the best fitting model, including a low symptoms class (48.9%, low probabilities of endorsing all ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation items), PTSD class (14.7%, elevated probabilities of endorsing PTSD items and low probabilities of all other items), CPTSD class (26.5%, elevated probabilities of endorsing CPTSD items and low probabilities of all dissociation items), and CPTSD + dissociation class (10%, high probabilities of endorsing all ICD-11 CPTSD and dissociation items); the CPTSD + dissociation class was found to have the poorest mental health and severest functional impairment. Less is known about the relationship between PTSD and dissociation in youths based on the perspective of person-centered methods. Given that posttraumatic reactions may manifest differently across different age groups (e.g. De Young & Landolt, Citation2018; Ferreira et al., Citation2023), there is a particular need for studies focusing on the dissociative subtype of CPTSD in traumatic youth.

Taken together, preliminary evidence in adult samples provides support for the proposition that there is a dissociative subtype of CPTSD. To further empirically test this proposition, especially among youth, would extend our knowledge on the association between CPTSD and dissociation, guide current thinking regarding placement of dissociation in the nosology of CPTSD, and inform clinically useful assessment and intervention. The present study aimed to investigate the co-occurring patterns of CPTSD and dissociative symptoms using LCA in a large sample of trauma exposed adolescents from China, and specify clinical covariate features across the patterns including childhood trauma, comorbidities with major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and functional impairment.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

The data were obtained from 57,984 high school students exposed to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. The participants included 28,089 (48.4%) males and 29,895 (51.6%) females with ages ranging from 11 to 20 years (Mean = 14.8 years; SD = 1.6). Detailed demographic characteristics can be found in Cao et al. (Citation2022).

The survey was conducted in Deyang city in Sichuan province, China, from July 13 and July 29, 2020, and organized by local education and health departments. A questionnaire survey with a brief screening tool was selected as the most economical and effective way of collecting data from a large sample in a short time. High school teachers sent a Wechat app QR code for the pre-prepared questionnaires to the guardian’s smartphone after providing a detailed introduction of the survey. Students participated in the survey voluntarily after signing electronic informed-consent forms together with their guardians. The ethics committee of the People’s Hospital of Deyang City approved this study.

2.2. Measures

The 7-item CPTSD and 2-item dissociation subscales of the Global Psychotrauma Screen for Teenagers (GPS-T) (Grace et al., Citation2021) were used to measure CPTSD and dissociative symptoms. The GPS-T is a brief screening tool to measure trauma-related symptoms and has been validated in the United States (Grace et al., Citation2021) and Greece (Koutsopoulou et al., Citation2024). The Chinese version of GPS-T was adapted by a stringent two-stage process of translation and back-translation and is available from the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (Citation2023). Respondents were instructed to complete the items with respect to the pandemic, and answer in ‘Yes’ (1) or ‘No’ (0) format. Cronbach’s α for the CPTSD and dissociation subscales were 0.83 and 0.64 in the present sample, respectively. Childhood (0–10 years) traumatic experience was inquired using the corresponding item from the risk factor subscale of the GPS-T, and this item was also rated on a ‘Yes’ (1) or ‘No’ (0) format. Functional impairment was measured with the functioning rating item of the GPS-T, and this item was rated using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Poor) to 10 (Excellent).

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale (Spitzer et al., Citation2006) were used to measure major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) symptoms, respectively. The items of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were rated using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Extremely). A cutoff of 10 for both the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) and GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., Citation2006) to detect possible MDD and GAD cases has been recommended in previous studies. The Chinese versions of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 have demonstrated good psychometric properties in adolescent samples (e.g. Leung et al., Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2021). Cronbach’s α for the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were 0.91 and 0.91 in the current sample, respectively.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The latent class analysis (LCA) was conducted with Mplus 7.0 using observed scores of CPTSD and dissociative symptoms. 1–6 classes were estimated and compared based on a set of fit indices. The optimal class solution should have lower values for the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC), a significant Lo – Mendell – Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR LRT), adjusted LMR LRT (ALMR LRT) and bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), a higher entropy value (values exceeding 0.70 are considered adequate), and adequate size of estimated classes (the smallest class sizes more than 5% of the sample are considered acceptable) (Nylund et al., Citation2007)

After optimal classes were extracted to SPSS 22.0, univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to examine between-class differences in scores of functional impairment, and hi-square tests were used to examine between-class differences in the proportion of MDD, GAD and early childhood trauma.

3. Results

The mean scores on the CPTSD subscale, dissociation subscale, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were 1.5 (SD = 2.0, range: 0–7), 0.2 (SD = 0.5, range: 0–2), 4.4 (SD = 4.9, range: 0–27) and 3.6 (SD = 3.9, range: 0–21), respectively.

The model fit indices of the six LCA models are presented in . As the number of classes increased, the smallest AIC and BIC values were not reached while the LMR LRT, ALMR LRT and BLRT values were consistently significant. However, the 6-class solution was rejected for having two classes with less than 5% of the sample. Therefore, the 5-class model emerged as the best-fitting model balancing model fit, acceptable class sizes and parsimony.

Table 1. Fit indices for latent class analyses.

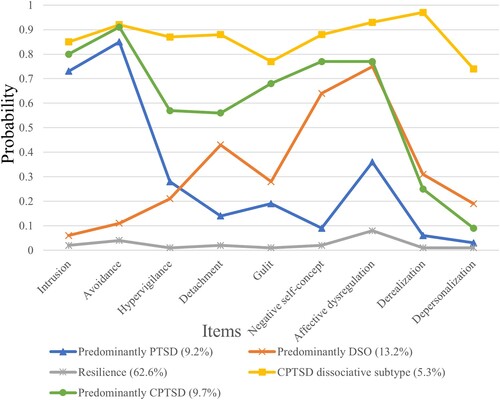

The profile plot for the 5-class profile is shown in . The five classes were labelled as resilience (62.6%, indicated by low endorsement of both CPTSD and dissociative symptoms), predominantly PTSD symptoms (9.2%, indicated by intermediate to high probability of endorsement of PTSD symptoms), predominantly DSO symptoms (13.2%, indicated by intermediate to high probability of endorsement of DSO symptoms), predominantly CPTSD symptoms (9.7%, indicated by intermediate to high probability of endorsement of CPTSD symptoms), and CPTSD dissociative subtype (5.3%, indicated by high probability of endorsement of both CPTSD and dissociative symptoms).

Figure 1. Symptom probabilities for the five-class solution for CPTSD and Dissociation items. DSO = Disturbances in self-organization.

Results of between-class comparisons are summarized in . Significant between-class differences in the proportion of MDD, GAD, childhood trauma and level of functioning (p < .001) were found. According to post-hoc tests, all five classes were significantly differentiated from each other in terms of all analyzed variables. Specifically, the CPTSD dissociative subtype class showed the lowest level of functioning and the highest rates of MDD, GAD and childhood trauma.

Table 2. Proportions of MDD/GAD/Childhood trauma and means of level of functioning for the five latent classes.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the co-occurring patterns of CPTSD and dissociative symptoms in traumatized youths. Results of LCA identified a distinct CPTSD dissociative subtype class (5.3%) from a predominantly CPTSD symptoms class (9.7%), which was generally congruent with previous work of Hyland et al. (Citation2024) with an adult sample. The finding suggests that a notable proportion of individuals with CPTSD symptoms (approximately 35.4%) might experience significant dissociative symptoms, and provides initial empirical evidence supporting the existence of a dissociative subtype of CPTSD. It has been argued that construct validity requires more evidence than LPA/LCA results alone (e.g. Achterhof et al., Citation2019; Ford, Citation2020), so more studies with various statistical processes are needed to support the validity of the dissociative subtype of CPTSD. The results of this study extend our understanding of the ways in which CPTSD and dissociation co-occur in trauma-exposed adolescents, and may be useful for both researchers and clinicians working with trauma-exposed adolescents.

We found that compared with the other classes, a significantly higher proportion of members in the CPTSD dissociative subtype class (approximate 33.8%) reported childhood traumatic experiences. Hyland et al. (Citation2024) reported that membership in the CPTSD + dissociation class was associated with several adverse childhood experiences such as verbal abuse, emotional neglect, and mental illness at home. Our study provides initial evidence for similar patterns in a younger sample. Previous studies also found childhood sexual and physical abuse to be associated with the DSM-5 dissociative subtype of PTSD (Hansen et al., Citation2017). As our study generally inquired participants on whether they experienced frightening or horrible events during early childhood, the current finding only suggests that threat-related early adverse experience might be a risk factor for the dissociative subtype of CPTSD. Research adopting the newly refined dimensional approach of early adverse experience (McLaughlin et al., Citation2021) should be conducted to further specify the associations between core elements of early environmental experience and trauma/stressors related to psychopathology.

In this study, the CPTSD dissociative subtype class was found to have higher comorbidity rates with MDD and GAD, and more severe functional impairment relative to the predominantly CPTSD symptoms class. The study of Hyland et al. (Citation2024) found that members in the CPTSD + dissociation class had higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms, and more severe functional impairment than those in the CPTSD class. Similarly, studies on the DSM-5 PTSD also reported that the dissociative subtype was associated with a high degree of psychiatric comorbidity, especially anxiety and depression, and severe functional impairment (Hansen et al., Citation2017; Schiavone et al., Citation2018). The findings suggest that the dissociative subtype of CPTSD would link to poorer mental health outcomes, and call for special attention on this psychiatric condition in clinical practice.

The current study carries several theoretical and clinical implications. First, although many previous studies have documented the association between CPTSD and dissociation (Fung et al., Citation2023; Hamer et al., Citation2024), theoretical models about the relationship between the two constructs have not yet been specified. Our finding that only some individuals with CPTSD symptoms might experience significant dissociative symptoms lends preliminary empirical evidence for a subtype model, and informs further theoretical discussion. Second, research on the DSM-5 dissociative subtype of PTSD has revealed particular pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the condition (Schiavone et al., Citation2018; Shaw et al., Citation2023; van Huijstee & Vermetten, Citation2018). The dissociative subtype of CPTSD identified in this study could also serve as a distinct clinical phenotype. Future neurobiological studies on this phenotype would advance current understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying trauma/stressors related to psychopathology, and inform the development of mechanistically driven intervention programmes. Third, this study found that the dissociative subtype of CPTSD would link to poorer mental health outcomes. Actually, dissociation also has been previously identified as an important factor affecting the treatment of CPTSD (Brewin, Citation2020). Thus, dissociation-related assessment and intervention should be considered in clinical practice on CPTSD.

Several limitations to this study should be noted. First, the findings were limited by our utilization of a sample exposed to a specific traumatic event (i.e. the COVID-19 pandemic) from China. Further studies using samples exposed to various traumatic events from other cultural backgrounds should be conducted to verify the current findings. Second, a self-reported questionnaire survey was selected as the most economical way of collecting data from a large sample. Thus, further replication using clinician-rated measures is warranted. Third, the GPS-T, a brief screening tool, was used as the most effective tool to measure CPTSD and dissociative symptoms. The GPS-T has some limitations. For example, CPTSD symptoms assessed with the GPS-T are not aligned with the ICD-11 criteria. Moreover, only two dissociative symptoms (i.e. depersonalization and derealization) were assessed and the other dissociative symptoms (i.e. dissociative amnesia) were not evaluated in this study. However, it should be noted that this is not merely a limitation of the GPS-T, the two assessed dissociative symptoms are the only forms of dissociation covered in the dissociative subtype of DSM-5 PTSD. Therefore, future research with measures capturing the ICD-11 criteria of CPTSD and a range of dissociative experiences would be helpful to further clarify the co-occurring patterns of CPTSD and dissociation.

Notwithstanding the limitations, the present study identified a dissociative subtype of ICD-11 CPTSD among trauma exposed youth, and found this condition was associated with poorer mental health outcomes. The findings contribute to extent knowledge on the association between CPTSD and dissociation, and inform further research and clinical practice on traumatized individuals.

Statement of ethics

Electronic informed consent was obtained from both students and their guardians. The study procedure and protocol were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of People’s Hospital of Deyang City (reference No. 2021-04-152-K01).

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge John D. Elhai for his help with manuscript editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achterhof, R., Huntjens, R. J., Meewisse, M. L., & Kiers, H. A. (2019). Assessing the application of latent class and latent profile analysis for evaluating the construct validity of complex posttraumatic stress disorder: Cautions and limitations. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1698223. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1698223

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Fifth edition. American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Brewin, C. R. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A new diagnosis in ICD-11. BJPsych Advances, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.48

- Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Maercker, A., Bryant, R. A., Humayun, A., Jones, L. M., Kagee, A., Rousseau, C., Somasundaram, D., Suzuki, Y., Wessely, S., van Ommeren, M., & Reed, G. M. (2017). A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.001

- Cao, C., Wang, L., Fang, R., Liu, P., Bi, Y., Luo, S., Grace, E., & Olff, M. (2022). Anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms among high school students in China in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 126–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.052

- Carlson, E. B., Dalenberg, C., & McDade-Montez, E. (2012). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder part I: Definitions and review of research. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(5), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027748

- Cloitre, M. (2020). ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress disorder: Simplifying diagnosis in trauma populations. British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(3), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.43

- Dalenberg, C., & Carlson, E. B. (2012). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder part II: How theoretical models fit the empirical evidence and recommendations for modifying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(6), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027900

- Dalenberg, C. J., Brand, B. L., Gleaves, D. H., Dorahy, M. J., Loewenstein, R. J., Cardeña, E., Frewen, P. A., Carlson, E. B., & Spiegel, D. (2012). Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 550–588. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027447

- De Young, A. C., & Landolt, M. A. (2018). PTSD in children below the age of 6 years. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(11), 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-018-0966-z

- Ferreira, F., Castro, D., & Ferreira, T. B. (2023). The modular structure of posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents. Current Psychology, 42(16), 13252–13264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02538-1

- Ford, J. D. (2020). New findings questioning the construct validity of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (cPTSD): let’s take a closer look. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1708145. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1708145

- Fung, H. W., Chien, W. T., Lam, S. K. K., & Ross, C. A. (2023). The relationship between dissociation and complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(5), 2966–2982. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221120835

- Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress. (2023). Global Psychotrauma Screen Teen Version, Chinese translation. https://zh.global-psychotrauma.net/_files/ugd/893421_4fc3653ca17e453f8e6a73b2d2420006.pdf.

- Grace, E., Sotilleo, S., Rogers, R., Doe, R., & Olff, M. (2021). Semantic adaptation of the Global Psychotrauma Screen for children and adolescents in the United States. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1911080. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1911080

- Hamer, R., Bestel, N., & Mackelprang, J. L. (2024). Dissociative symptoms in complex posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 25(2), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2023.2293785

- Hansen, M., Ross, J., & Armour, C. (2017). Evidence of the dissociative PTSD subtype: A systematic literature review of latent class and profile analytic studies of PTSD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.004

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050305

- Hyland, P., Hamer, R., Fox, R., Vallières, F., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., & Cloitre, M. (2024). Is dissociation a fundamental component of ICD-11 complex posttraumatic stress disorder? Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 25(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2023.2231928

- Koutsopoulou, I., Grace, E., Gkintoni, E., & Olff, M. (2024). Validation of the global psychotrauma screen for adolescents in Greece. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8, 100384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2024.100384

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Leiva-Bianchi, M., Nvo-Fernandez, M., Villacura-Herrera, C., Miño-Reyes, V., & Parra Varela, N. (2023). What are the predictive variables that increase the risk of developing a complex trauma? A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 343, 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.10.002

- Leung, D. Y., Mak, Y. W., Leung, S. F., Chiang, V. C., & Loke, A. Y. (2020). Measurement invariances of the PHQ-9 across gender and age groups in Chinese adolescents. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 12(3), e12381. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12381

- Maercker, A., Cloitre, M., Bachem, R., Schlumpf, Y. R., Khoury, B., Hitchcock, C., & Bohus, M. (2022). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet, 400(10345), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

- McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., Humphreys, K. L., Belsky, J., & Ellis, B. J. (2021). The value of dimensional models of early experience: Thinking clearly about concepts and categories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1463–1472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621992346

- Misitano, A., Moro, A. S., Ferro, M., & Forresi, B. (in press). The dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of the literature using the latent profile analysis. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2022.2120155

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Redican, E., Nolan, E., Hyland, P., Cloitre, M., McBride, O., Karatzias, T., Murphy, J., & Shevlin, M. (2021). A systematic literature review of factor analytic and mixture models of ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102381

- Schiavone, F. L., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M., & Lanius, R. A. (2018). The dissociative subtype of PTSD: An update of the literature. PTSD Research Quarterly, 29(3), 1–13. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/.

- Shaw, S. B., Terpou, B. A., Densmore, M., Théberge, J., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2023). Large-scale functional hyperconnectivity patterns in trauma-related dissociation: An rs-fMRI study of PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Nature Mental Health, 1(10), 711–721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00115-y

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Sun, J., Liang, K., Chi, X., & Chen, S. (2021). Psychometric properties of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 item (GAD-7) in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Healthcare, 9(12), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121709

- van Huijstee, J., & Vermetten, E. (2018). The dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder: Research update on clinical and neurobiological features. In E. Vermetten, D. G. Baker, & V. B. Risbrough (Eds.), Behavioral neurobiology of PTSD (Vol. 38, pp. 229–248). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2017_33.

- Vonderlin, R., Kleindienst, N., Alpers, G. W., Bohus, M., Lyssenko, L., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Dissociation in victims of childhood abuse or neglect: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2467–2476. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718000740

- White, W. F., Burgess, A., Dalgleish, T., Halligan, S., Hiller, R., Oxley, A., Smith, P., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2022). Prevalence of the dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 52(9), 1629–1644. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722001647

- World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en.