ABSTRACT

Background: Despite its popularity, evidence of the effectiveness of Psychological First Aid (PFA) is scarce.

Objective: To assess whether PFA, compared to psychoeducation (PsyEd), an attention placebo control, reduces PTSD and depressive symptoms three months post-intervention.

Methods: In two emergency departments, 166 recent-trauma adult survivors were randomised to a single session of PFA (n = 78) (active listening, breathing retraining, categorisation of needs, assisted referral to social networks, and PsyEd) or stand-alone PsyEd (n = 88). PTSD and depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline (T0), one (T1), and three months post-intervention (T2) with the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C at T0 and PCL-S at T1/T2) and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Self-reported side effects, post-trauma increased alcohol/substance consumption and interpersonal conflicts, and use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine were also explored.

Results: 86 participants (51.81% of those randomised) dropped out at T2. A significant proportion of participants in the PsyEd group also received PFA components (i.e. contamination). From T0 to T2, we did not find a significant advantage of PFA in reducing PTSD (p = .148) or depressive symptoms (p = .201). However, we found a significant dose–response effect between the number of delivered components, session duration, and PTSD symptom reduction. No significant difference in self-reported adverse effects was found. At T2, a smaller proportion of participants assigned to PFA reported increased consumption of alcohol/substances (OR = 0.09, p = .003), interpersonal conflicts (OR = 0.27, p = .014), and having used psychotropics (OR = 0.23, p = .013) or sick leave (OR = 0.11, p = .047).

Conclusions: Three months post-intervention, we did not find evidence that PFA outperforms PsyEd in reducing PTSD or depressive symptoms. Contamination may have affected our results. PFA, nonetheless, appears to be promising in modifying some post-trauma behaviours. Further research is needed.

HIGHLIGHTS

Psychological First Aid (PFA) is widely recommended early after trauma.

We assessed PFA's effectiveness for decreasing PTSD symptoms and other problems 3 months post-trauma.

We didn't find definitive evidence of PFA’s effectiveness. Still, it seems to be a safe intervention.

Antecedentes: A pesar de su popularidad, la evidencia sobre la efectividad de los Primeros Auxilios Psicológicos (PAP) es escasa.

Objetivo: Evaluar si los PAP, en comparación con la psicoeducación (PsiEd), un control de placebo atencional, reducen los síntomas de PTSD y depresión tres meses después de la intervención.

Método: En dos servicios de urgencia, 166 adultos sobrevivientes de traumas recientes fueron asignados aleatoriamente a una sola sesión de PAP (n = 78) (escucha activa, ejercicios de respiración, categorización de necesidades, derivación asistida a redes sociales y PsiEd) o a PsiEd sola (n = 88). Los síntomas de PTSD y depresión fueron evaluados al inicio (T0), uno (T1) y tres meses después de la intervención (T2) con el PTSD Checklist (PCL-C en T0 y PCL-S en T1/T2) y el Inventario de Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II). También se exploró el autoreporte de efectos adversos, consumo de alcohol/sustancias, conflictos interpersonales, y uso de psicotrópicos, psicoterapia, licencia por enfermedad y medicina complementaria/alternativa.

Resultados: 86 participantes (51,81% de los aleatorizados) abandonaron en T2. Una proporción significativa de participantes en el grupo PsiEd también recibió componentes de PAP (es decir, hubo contaminación). De T0 a T2, no encontramos una ventaja significativa de PAP en la reducción de síntomas de PTSD (p = .148) o depresión (p = .201). Sin embargo, encontramos un efecto dosis-respuesta significativo entre el número de componentes entregados o la duración de la sesión y la reducción de síntomas de PTSD. No encontramos diferencias significativas en efectos adversos. En T2, una proporción menor de participantes asignados a PAP reportó un aumento en el consumo de alcohol/sustancias (OR = 0.09, p = .003), conflictos interpersonales (OR = 0.27, p = .014), y uso de psicotrópicos (OR = 0.23, p = .013) o licencia por enfermedad (OR = 0.11, p = .047).

Conclusiones: Tres meses después de la intervención, no encontramos evidencia de que los PAP superen a PsiEd en la reducción de síntomas de PTSD o depresión. La contaminación pudo haber afectado nuestros resultados. Sin embargo, los PAP parecen ser prometedores en la modificación de algunos comportamientos postraumáticos. Se necesita más investigación.

1. Introduction

About 70% of the world’s population has experienced trauma (Kessler et al., Citation2017). Climate change, political conflicts and epidemiological threats could increase trauma exposure in the following years (Bowles et al., Citation2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common mental condition after trauma. In a survey of 68,894 participants from 24 countries, the risk of developing PTSD after any trauma was 4%, with the highest risk among victims of rape (19%) (Kessler et al., Citation2017). PTSD has been associated with a higher risk of suicide, secondary comorbidity, role functioning disruption, and loss of life course opportunities (Kessler, Citation2000).

Psychological First Aid (PFA) is an early psychosocial intervention for reducing initial distress and fostering adaptive functioning in trauma victims (Vernberg et al., Citation2008). It has been defined as a ‘humane, supportive response to a fellow human being who is suffering and who may need support. It entails basic, non-intrusive pragmatic care with a focus on listening but not forcing talk, assessing needs and concerns, ensuring that basic needs are met, encouraging social support from significant others and protecting from further harm’ (No authors, Citation2010). PFA is endorsed by the World Health Organisation (World Health Organization, World Trauma Foundation & World Vision International, Citation2011) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC Reference Centre for Psychosocial Support, Citation2018), among other international organisations.

Although there are many models of PFA, all of them seek to increase safety, calm, self-efficacy, connection, and hope, five empirically supported principles widely known as ‘Hobfoll’s essential elements’. PFA fosters Hobfoll’s elements through active listening, relaxation, problem-solving, and social connection (Wang et al., Citation2024). According to the literature on trauma and disaster recovery and expert consensus, Hobfoll’s essential elements should guide early post-trauma interventions (Hobfoll et al., Citation2007). They are aimed at bringing immediate emotional relief, preventing traumatisation, and promoting adaptive coping through rapid interruption of the traumatic stimulus, modulation of agitation and hyperarousal, increase in the notion of self – and collective efficacy, increase of received and perceived social support, mitigation of self-defeating thoughts, and fostering positive behaviours (Wang et al., Citation2024). Notably, more than complex psychological manoeuvres, PFA was conceived to enhance Hobfoll’s essential elements through rapid, simple, and pragmatic actions, such as normalisation, breathing retraining, ‘problem-solving’, and ‘practical assistance’, among others. These actions can be provided even in single sessions. The notion that such rapid, brief, and simple actions can be effective is supported by six trials in which PFA was delivered in just one session, all of them showing promising results in decreasing PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms (Wang et al., Citation2024).

Despite the widespread use of PFA, there is a paucity of evidence to support its effectiveness and safety. Several challenges have hampered PFA research, such as its inherent flexibility that limits standardisation and the complexity of conducting programme evaluation research in emergency and disaster contexts (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023). Bisson and Lewis (Citation2009) published in 2009 the results of the first meta-analysis on PFA, concluding that their literature search ‘revealed no randomised-controlled trials (RCT), observational or any other empirical study of PFA.’ More than one decade later, a new systematic review by Hermosilla et al. (Citation2023) found only twelve empirical studies and just one RCT about PFA. Although all of them showed a positive effect of PFA, mostly on anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and distress, several limitations, such as inconsistent intervention components, insufficient evaluation methodologies, and a high risk of bias, precluded firm conclusions. Consequently, experts have urgently called for further research (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023; Shultz & Forbes, Citation2014).

Acknowledged as ‘the most robust trial’ in the last systematic review of PFA (Wang et al., Citation2024), Figueroa et al. studied a sample of 221 adult non-intentional trauma survivors visiting five emergency departments in Chile (Figueroa et al., Citation2022). They showed that a single 30–60-min PFA session relieved participants’ psychological distress immediately after its delivery and that PFA was associated with fewer PTSD symptoms one – but no six-months post-intervention, compared to psychoeducation. In this study, we aimed to replicate Figueroa et al.’s trial but assess PFA’s effect at three months post-intervention, an intermediate endpoint that was not previously explored. To determine PFA’s effect, we also used mixed-effects models, a more robust methodology to deal with longitudinal data compared to traditional linear regressions (Oberg & Mahoney, Citation2007). Additionally, we recorded the components of the experimental and control conditions that were effectively delivered. This crucial information about the protocol components that are truly provided has been absent in most available PFA trials, hindering the study of PFA mechanisms (Wang et al., Citation2024). Furthermore, in this study, we also explored PFA’s impact on other significant outcomes besides symptom control, namely self-reported side effects, increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, increased post-trauma interpersonal conflicts, and use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine to deal with post-traumatic emotional distress. We hypothesised that at three months post-intervention, PFA would outperform PsyEd in decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms, that it would not be associated with increased odds of self-reported adverse effects, and that fewer participants assigned to PFA would report increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, increased post-trauma interpersonal conflicts, and post-trauma use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study was an RCT with two parallel groups: PFA and PsyEd. As in Figueroa et al. (Citation2022) and upon discussing the ethical implications of leaving recent trauma survivors without any formal support, we decided to use PsyEd as an attention placebo control (APC). APC is regarded as a highly valid control condition in social intervention research (Popp & Schneider, Citation2015). APCs are analogous to pill placebos in drug trials, aimed at controlling nonspecific effects of the intervention, such as attention, treatment contact, social support, and nonspecific therapist effects (Pagoto et al., Citation2013). For an intervention to be considered a good APC, it needs to mimic the experimental intervention’s nonspecific, theoretically inactive components. PsyEd can be regarded as an effective APC of PFA because it provides attention and treatment contact, like PFA, but has not been shown to decrease PTSD or depression symptoms as a stand-alone intervention, according to a recent systematic review of ten studies in which none of them showed a significant effect compared to no or other interventions (Brooks et al., Citation2021). Moreover, as long as PsyEd has failed to show a significant impact on decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms in recent trauma survivors compared to no intervention, treatment as usual, or waiting list, it can be reasonably assumed that the symptomatic trajectories exhibited by participants assigned to PsyEd are a valid proxy of the natural course of PTSD and depressive symptoms and, consequently, any differential effect of PFA vs PsyEd could be considered a proxy of PFA’s effectiveness (Laursen et al., Citation2020).

In this study, participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to the active and control conditions. Recruitment occurred from June 12th to July 28th, 2017; follow-ups were completed by October 31st, 2017. The study was conducted in the emergency departments (ED) of two academic hospitals in Chile. The ethical committees of both hospitals approved the protocol.

2.2. Sample size

Based on Figueroa et al. (Citation2022), we aimed to detect a mean difference of seven points in the PTSD Checklist (PCL) scores with alpha 5% (two-sided) and beta 80%. This required a sample size of 166 participants, assuming a standard deviation (S.D.) of 16 points.

2.3. Participants

Participants were 166 adults 18 years or older visiting an ED as a patient or companion and exposed to trauma no more than 72 hours before. Events were considered trauma if they met the PTSD A-criterion of the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Medical conditions were regarded as trauma only when they were sudden and threatened life or physical integrity. Companions were invited to participate in the study only when they witnessed trauma in person or learned that a close family member or friend had experienced an unexpected, violent, or accidental traumatic event. Exclusion criteria included not speaking Spanish, illiteracy, agitated, violent, or disruptive behaviour, physiological instability requiring medical intervention, a close relative in imminent agony, amnesia, brain concussion, lack of telephone, psychosis, or suicide attempt, all of them present at the time of the recruitment. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed using a self-reported checklist, the attending physician’s opinion, and medical records when available.

2.4. Providers

The providers were five psychology students in their 4th year who finished an 8-hour PFA training comprising lectures and role-playing. The training included topics on traumatic stress, the whole PFA protocol, and self-care. In addition, they received 8 hours of training on enrolment, randomisation, blinding and data collection. The PFA training was comparable to other courses (Ni et al., Citation2023). Providers’ competencies on PFA were ensured with a post-training test that included alternative questions and a simulation with actors. Further information on providers’ training can be found elsewhere (Figueroa et al., Citation2022). Providers received payment for their service. They were responsible for searching eligible survivors, enrolling participants, collecting baseline data, and delivering the allocated intervention. Because stand-alone PsyEd is also a component of the whole PFA protocol (step E) and PFA and PsyEd providers were the same psychology students, PsyEd training was regarded as a part of the entire PFA training.

2.5. Recruitment and enrolment

Emergency room triage nurses notified providers if a patient or companion showed psychological distress (e.g., crying, screaming, yelling, complaining). Providers approached these individuals and offered an opportunity to participate in a medical study to evaluate the effectiveness of a ‘psychological intervention’ to deliver immediate emotional relief and prevent posterior psychological problems. No more explanations about the study’s hypothesis were given, and technical explanations were withheld to avoid expectancy. A brochure outlining the study’s possible benefits and risks was offered. Those who expressed interest were registered, and eligibility was assessed. Those eligible signed an informed consent document. The recruitment finished when the calculated sample size was reached. The follow-up ended after all participants were evaluated or declared lost to follow-up. We did not consider any interim analyses or stopping guidelines.

2.6. Randomisation

Before starting the study, one author obtained a random sequence of digits zero or one in identical proportions from the website random.org. No restrictions, such as blocking, were set. Two researchers kept the allocation sequence concealed. After enrolment, providers collected baseline data with paper and pencil at the bedside for patients or in a quiet and private room for companions. Providers were allowed to clarify participants’ questions but not to respond to their questionnaires. After collecting baseline data, an author randomly allocated participants to PFA or PsyEd by phone. Participants remained blind to their allocation during the study. The same provider who enrolled the participant delivered the assigned intervention. PFA and PsyEd were similar in that the same providers provided both interventions in the same areas and with the same written material, facilitating blinding. Providers did not know the study’s hypotheses.

2.7. Interventions

Participants assigned to PFA received a single session of PFA immediately after allocation, according to the PFA-ABCDE protocol (Cortés Montenegro & Figueroa Cabello, Citation2019). The ABCDE protocol entails five steps to foster Hobfoll’s essential elements (Hobfoll et al., Citation2007). Each step is named after their first letter, forming a mnemonic. The whole protocol is delivered in 30–60 minutes. Depending on clinical needs, steps can be swapped or exceptionally omitted. The steps are:

| A. | Active listening (10–20 min), in which the survivor can talk without interruption, and the caregiver shows empathy through listening, paraphrasing and reflection. The goal is to provide reassurance through empathic companionship. | ||||

| B. | Breathing retraining (5–10 min), which consists of a breathing exercise to bring calm through prolonged exhalation. Recent evidence shows that prolonged exhalation increases heart rate variability, presumably linked to a stimulation of the vagal tone that may lead to a calming effect (Bae et al., Citation2021). | ||||

| C. | Categorisation of needs (5–10 min), which involves assisting the survivor in identifying and prioritising their most pressing needs and concerns, such as communication with relatives, information, legal issues, or social services. The aim is to help the survivor regain control of the situation and foster goal-oriented thinking. | ||||

| D. | Referral (equivalent to Derivación in Spanish) (5–10 min) involves referring survivors to the social support networks that best meet the needs identified in step C. To implement step D, providers personally get survivors in connection with adequate social support networks by making phone calls or accompanying participants in situ to get in contact with relatives, friends, or social service workers. When immediate access to social support networks is not feasible, a plan is made with the active participation of the survivor. This step is facilitated through a booklet containing details on public health and social protection services, including a 24/7 telephone line for health-related matters. The importance of regular social support and maintaining close relationships with family and friends is discussed, and those requiring formal mental health are formally referred. | ||||

| E. | psychoEducation (5–10 min) provides information about common reactions to trauma, warning signs, adaptive coping strategies, access to mental healthcare, and myths. Step E is also supported with a booklet. The name of this step is written with uppercase ‘E’ to signal its place in the ABCDE mnemonic. | ||||

Participants assigned to the control condition were offered PsyEd as a stand-alone intervention, identical to PFA’s step E, and delivered by the same providers, with the same written material, in the same places. For ethical reasons, we allowed providers to provide other PFA components besides step E to participants assigned to PsyEd who explicitly requested them. Hence, the truly delivered steps and the starting and ending times of the intervention were registered to check protocol integrity. The proportion of participants assigned to PFA or PsyEd who received steps A, B, C, D, and E was 89.3 vs 30.0%, 74.3 vs 7.8%, 40.5 vs 1.3%, 49.3 vs 24.1%, and 94.7 vs 95.2%, respectively. The mean (S.D.) duration of PFA was 35.3 min (32.57), whereas PsyEd lasted 16.8 min (13.93). Overall, PFA differed from PsyEd in that, on average, it was about 50% longer and included components A, B, C, or D in a significantly higher proportion of participants.

An English version of the intervention manual can be downloaded for free at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile School of Medicine website: https://medicina.uc.cl/publicacion/manual-abcde-la-aplicacion-primeros-auxilios-psicologicos/.

2.8. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the effect of the intervention on the reduction of PTSD and depressive symptoms three months post-intervention. Secondary outcomes included self-reported side effects, increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, increased post-trauma interpersonal conflicts, and post-trauma use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine to deal with post-traumatic distress.

Baseline data, including demographic information, vital signs, trauma history, PTSD and depressive symptoms, and peritraumatic dissociation, were collected by providers in the ED immediately after participants gave informed consent at T0. A team of specialised operators blind to the participant’s allocation collected data by phone one (T1) and three months (T2) post-intervention.

2.8.1. Instruments

2.8.1.1. Demographic information

Demographic information was assessed using the demographics section of the WHO World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Spanish version 2.1 (World Health Organization, Citation1997).

2.8.1.2. PTSD symptoms

We used the Spanish version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) to assess PTSD symptoms in the last month (Weathers et al., Citation1993). The ‘civilian version’ of the PCL (PCL-C), which referred to any previous traumatic event, including the one that brought the participant to the ED, was used at T0. The ‘specific version’ (PCL-S), which referred exclusively to the trauma that brought the participant to the ED, was used at T1 and T2. Both versions of the PCL are a 17-item, self-reported instrument based on the Fourth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Each item is answered on a one (not at all) to five (extremely) Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 17 to 85 and higher scores indicating higher PTSD symptoms. For our study, we chose to use the PCL, which is based on the DSM-IV criteria, instead of the PCL-5, which is based on the DSM-5, because when the study was implemented, the PCL was the only option validated in Chile. For diagnosing ‘probable PTSD’, we used a cut-point score ≥ 44, assuming a prevalence of PTSD diagnosis of about 25% at T1 based on Figueroa et al. (Citation2022), and considering the recommendation of the National Center for PTSD (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL_handoutDSM4.pdf). The PCL showed excellent internal consistency in a sample of adults affected by the 2010 earthquake in Chile (0.89) (Vera-Villarroel et al., Citation2011). In our sample, the PCL showed excellent internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .93 at T0, .93 at T1, and .92 at T2).

2.8.1.3. Depressive symptoms

To evaluate depressive symptoms, we employed the Spanish version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., Citation1996). The BDI-II is a self-report instrument with 21 items and four possible answers, 0–3, with total scores ranging from 0 to 63 and higher scores signalling higher depressive symptoms. It was validated in Chile, showing Cronbach’s alphas ranging between .89 and .91 (Melipillán Araneda et al., Citation2008). In our sample, the BDI-II showed good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .90 at T0, .89 at T1, and .86 at T2).

2.8.1.4. Peritraumatic dissociation

We employed the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ) to measure peritraumatic dissociation symptoms linked to the traumatic event that brought the participant to the ED (Marmar et al., Citation1997). The PDEQ is a 10-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the following phenomena with a 5-point scale of 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘extremely true’): losing track of time; acting automatically; feeling as though time was changing; feeling as though one was floating above the scene; feeling disconnected from own’s body; confusion; not being aware of what is happening; and disorientation. It yields a 7–35 total score range, with a higher score reflecting higher peritraumatic dissociation symptoms. The PDEQ has proven to be discriminant, predictive, convergent, and reliable, with Cronbach’s alpha scores ranging from .81 to .85 (Marshall et al., Citation2002). The similarity between the English and Spanish versions of the PDEQ was established by Marshall and Orlando (Citation2002). The Chilean-Spanish version was validated in a sample of firefighters (Ramos et al., Citation2022). In our sample, its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was .84, indicating good reliability.

2.8.1.5. Number of different previous traumas

Lifetime exposure to traumatic events was evaluated with the Trauma Questionnaire (TQ) (Escalona et al., Citation1997) at T0. This self-report questionnaire assesses lifetime exposure to 18 types of self-experienced or witnessed traumatic events. Each event is answered ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ independently of the number of times it occurred. The Spanish version (Bobes et al., Citation2000) has demonstrated adequate test-retest reliability, discriminant validity, and concurrent validity. We calculated a total score by adding the total number of different previous traumatic events reported by the participant.

2.8.1.6. Other post-trauma phenomena

We used not validated, close-ended, yes/no questions at T1 and T2 to assess self-reported side effects and six post-trauma behaviours: increased alcohol/substance consumption, increased interpersonal conflicts, use of psychotropics, use of psychotherapy, use of sick leave, and use of complementary/alternative medicine, the last four ‘to deal with post-traumatic distress’ (see ). We explored these phenomena only dichotomously (i.e. yes/no); hence, for example, the number of days off work due to sick leave or the amount of increased alcohol consumption was not explored. Self-reported adverse effects were also assessed immediately after the intervention.

2.9. Analytical methods

All analyses were conducted intention-to-treat with a significance threshold of p < .05. We performed all calculations using R.

The intervention’s effect on the change of PTSD and depressive symptom scores from T0 to T2 was modelled with linear mixed-effect models. Independent predictors of PTSD and depressive symptoms at T2, the experimental condition among them, were modelled with multiple linear regressions. To increase statistical power and protect against baseline imbalance (Kahan et al., Citation2014), we included baseline depressive symptoms as a covariate in all calculations, given its large predicting effect on PTSD symptomatology (Worthington et al., Citation2020) and its previous use by Figueroa et al. (Citation2022). Baseline PTSD symptoms were not included as a covariate due to large multicollinearity with baseline depressive symptoms (r = .692, p < .001). In the mixed-effect models, time (measured in months with 0 representing baseline), condition, baseline depressive symptoms, and the interaction between time and condition were included as independent fixed variables. Random effects were incorporated to account for the interdependence of observations within the same individuals. We sensitised our mixed models by adding baseline education, peritraumatic dissociative symptoms, and the number of different previous traumas as covariates. We also modelled the effect of the interaction time × session duration and time × number of delivered components. All variables were centred.

Independent predictors of probable PTSD diagnosis and PTSD and depressive symptoms at T2 were modelled with stepwise multiple regressions by backward elimination of the following covariates: baseline depressive symptoms, condition, education, number of previous traumas, and peritraumatic dissociative symptoms.

The intervention’s effect on self-reported side effects, increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, increased post-trauma interpersonal conflicts, and post-trauma use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine was evaluated with logistic regressions comparing the odds of answering ‘yes’ by participants assigned to PFA versus PsyEd.

Missingness was handled within mixed-effect models by Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML), assuming missingness at random (MAR). Missingness in linear and logistic regression models was managed with multiple imputations of missing data by chain equations (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Citation2011), assuming missingness at random (MAR). We imputed data using highly correlated coauxiliars (Spearman’s Rho ≥ .4) with less than 10% missingness (Hardt et al., Citation2012). Five datasets were imputed after 70 iterations. Assessment of density plots and the R-hat statistic showed convergence in all imputed datasets.

3. Results

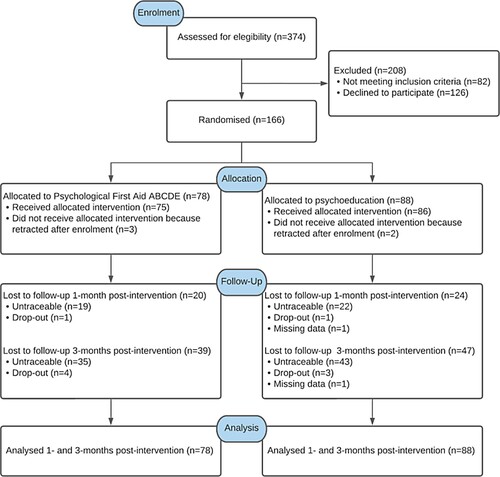

A total of 374 individuals were screened for eligibility. Of them, 166 (44.4%) were randomised to receive PFA (N = 78, 47%) or PsyEd (N = 88, 53%) ().

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants through the study.

The attrition rate was high and equivalent in both groups. A total of 44 participants (26.51% of those randomised) dropped out at T1, and 86 participants (51.81% of those randomised) dropped out at T2, with no significant differences between conditions (OR = 0.920, p = .812 at T1; OR = 0.872, p = .661 at T2). The main reason for attrition was no traceability.

Most participants were middle-aged (mean = 41.21 years, S.D. = 13.48) females (65.66%), with a mean of about twelve years of formal education (mean = 12.29, S.D. = 3.45), moderate mean baseline PTSD symptoms (mean = 40.80, S.D. = 16.67), mild mean baseline depressive symptoms (mean = 14.92, S.D. = 11.19), and lifetime exposure to more than two previous different types of traumas (mean = 2.60, S.D. = 2.09). Learning that a close family member or friend was exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence was the most frequent trauma (25.30%), followed by sudden medical conditions threatening life or physical integrity (16.87%) and motor vehicle accidents (15.06%) ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

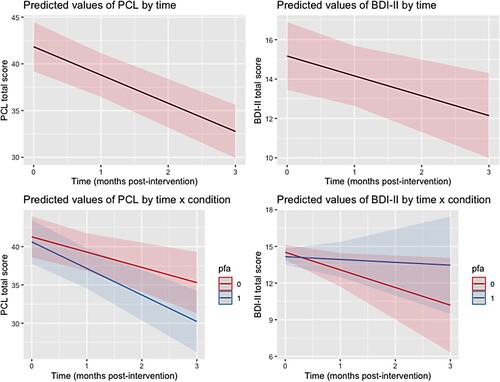

We found a significant decrease of PTSD symptoms (Β = −3.02, Std. Error = 0.49, β = −.20, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (B = −1.01, Std. Error = 0.39, β = −.11, p = .012) between T0 and T2. However, we did not find a significant interaction between time and the experimental condition for PTSD (B = −1.47, Std. Error = 1.01, β = −.05, p = .148) or depressive symptoms (B = 1.21, Std. Error = 0.94, β = .07, p = .201) ( and ). After sensitisation, the effect of PFA on PTSD and depressive symptoms reduction remained not statistically significant. We found, however, that longer session duration (B = −0.05, Std. Error = 0.02, β = −.08, p = .033) and a higher number of delivered components (B = −0.80, Std. Error = 0.37, β = −.10, p = .030) were associated with a steeper decrease of PTSD symptoms, pointing out to a dose–response effect. We did not find such a dose–response effect in depressive symptoms (effect of session duration: p = .837; effect of the number of delivered components: p = .827).

Figure 2. Predicted values of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) in linear mixed-effect models; pfa: Participants assigned to Psychological First Aid (0 = no; 1 = yes). Shadows represent 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2. Fixed effects of time × condition interaction on PTSD and depressive symptoms assessed with Linear Mixed-Effect ModelsTable Footnotea.

At T2 and after backward elimination of covariates in multiple linear regressions, only the experimental condition and baseline depressive symptoms remained significant predictors of PTSD symptoms (PFA – PsyEd adjusted mean difference at T2 = −6.41, Cohen’s d = −0.45, p = .03). Baseline depressive symptoms was the only covariate that remained a significant predictor of depressive symptoms at T2 (B = 0.27, Std. Error = 0.11, p = .021). Four (10.3%) and 13 (31.7%) participants had ‘probable PTSD’ in the PFA vs PsyEd groups, respectively (PFA OR = .25, p = .028). The experimental condition, peritraumatic dissociation, and baseline PTSD symptoms were the only variables that remained significant predictors of ‘probable PTSD’ diagnosis at T2 after stepwise backward elimination of covariables in logistic regressions (PFA OR = .126, Std. Error = 0.81, p = .013).

The proportion of participants who reported adverse effects at T2 did not differ between conditions immediately after the intervention (OR = 1.53, p = .520), at T1 (OR = 3.13, p = .127), or at T2 (OR = 0.46, p = .402) (). Interestingly, at T2, fewer participants in the PFA group reported increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption (OR = 0.09, p = 0.003), increased interpersonal conflicts (OR = 0.27, p = .014), and having used psychotropics (OR = 0.23, p = .013) or sick leave (OR = 0.11, p = .047). We did not find a significant effect of PFA on any binary outcome at T1, nor self-reported use of psychotherapy or complementary/alternative medicine at T2.

Table 3. Post-traumatic behaviours assessed one and three months post-intervention.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of an early single session of PFA-ABCDE, compared to PsyEd, on decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms three months post-intervention. We also assessed PFA’s association with self-reported side effects, increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, increased post-trauma interpersonal conflicts, and post-trauma use of psychotropics, psychotherapy, sick leave, and complementary/alternative medicine to deal with post-traumatic distress.

Contrary to our hypothesis, PFA did not decrease PTSD or depressive symptoms to a greater extent than PsyEd three months post-intervention. PFA was not associated with increased odds of self-reported adverse effects at any follow-up. At T2, fewer participants in the PFA group reported increased consumption of post-trauma alcohol/substances, interpersonal conflicts, and having used psychotropics or sick leave to deal with post-traumatic emotional distress. Participants assigned to PFA and PsyEd exhibited a similar decrease in PTSD and depressive symptoms. Because PsyEd has failed to demonstrate effectiveness for decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms, it is plausible that the equivalent reduction in symptoms observed in both PFA and PsyEd corresponded to natural recovery.

The lack of a significant effect of PFA on decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms between T0 and T2 may be explained by treatment similarity, natural recovery, an insufficient number of sessions or baseline noise. As providers were allowed, for ethical reasons, not to deny support spontaneously requested by participants assigned to PsyEd, 30.0% and 24.1% of participants assigned to control also received steps A and D, respectively. Therefore, contamination may have obscured the distinction between conditions, increasing the risk of type 2 error (Magill et al., Citation2019). This notion is supported by the significant dose–response effect that was found between the duration of sessions, the number of delivered components, and the slope of PTSD symptoms between T0 and T2. Moreover, using an APC instead of a waitlist may have further increased contamination by providing the same theoretically inactive and unspecific components of PFA to participants assigned to the control group. It is also possible that PsyEd (step E) was the only active ingredient, although this is unlikely according to the literature (Brooks et al., Citation2021). The substantial number of participants in the control group who received treatments A and C underscores the ethical complexities encountered in psychosocial intervention research with control groups, where balancing the need to maintain treatment fidelity with ethical considerations poses a notable challenge (Street & Luoma, Citation2002).

As we did not exclude individuals with a low risk of developing PTSD, it is feasible that most participants in our study recovered spontaneously because natural recovery is the norm (Galatzer-Levy et al., Citation2018). Hence, in our low-risk sample, the putative benefit of PFA for decreasing PTSD and depressive symptoms could have vanished soon after the intervention. Conversely, in a high-risk population, PFA’s effect could be larger and last longer, requiring a smaller sample size to be detected. This phenomenon highlights the importance of targeting high-risk survivors in early intervention research.

In this study, we only delivered a single session of PFA, although PFA guidelines allow additional sessions (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023). Hence, insufficient sessions may also explain why we did not find a significant effect. However, it is not evident that more sessions would entail higher probabilities of finding a significant effect. For example, McCart et al. (Citation2020) found no significant effect of two to three PFA sessions on decreasing PTSD symptoms in a sample of 172 crime survivors assessed four months post-intervention. More research will be needed to explore whether more than a single session of PFA is required to reduce PTSD and depressive symptoms.

Importantly, measuring baseline PTSD symptoms with the PCL-C, which referred to any previous traumas, including the recent incident leading to ED presentation, instead of using the PCL-S for specifying the scope to only the recent incident that brought the participant to the ED, may have introduced noise. This variability could have compromised the precision of our baseline measurements, thus diminishing our statistical power. Nonetheless, the significant effect of PFA on ‘probable PTSD’ and PTSD symptoms at the T2 follow-up – outcomes that remain unaffected by the baseline noise introduced by the PCL-C – suggests a meaningful effect. This implication is nuanced by the fact that baseline imbalances, better adjusted in longitudinal analyses, are still possible in the cross-sectional evaluation of follow-up scores despite adding baseline covariates in the models. These differences between change and follow-up scores may account for the observed discrepancies between both approaches. Additionally, the initial use of the PCL-C might have led to elevated PTSD symptom scores at baseline in comparison with follow-up assessments. However, we have no compelling evidence to suggest that this potential inflation of baseline scores systematically favoured one experimental group over another.

The significant effect of PFA on alcohol/substance consumption, interpersonal conflicts, use of psychotropics, and use of sick leave is noteworthy. It is plausible that active listening (step A), breathing retraining (step B), an assisted categorisation of needs (step C), or an assisted referral to social networks (step D) may have increased perceived and received social support (Uchino, Citation2009; Bodie et al., Citation2015) and emotional regulation (Bae et al., Citation2021; Ma et al., Citation2017; Sahar et al., Citation2001). These factors have been linked to increased self-efficacy and adaptive coping (Amstadter & Vernon, Citation2008; Schwarzer & Knoll, Citation2007), which, in turn, may lead to a reduced need for alcohol/substances, psychotropics, or sick leave to cope with post-traumatic distress (Hawn et al., Citation2020). Moreover, an enhanced emotional regulation might appease post-traumatic hyperarousal, a factor that seems to mediate increased interpersonal conflicts in PTSD (Beck et al., Citation2009). These ideas are speculative and should be cautiously approached, requiring additional research for validation.

This study has significant limitations that warrant careful consideration of our results. Our high attrition rate may have produced systematic bias and reduced our statistical power. To address this limitation, we used mixed models and multiple imputations. We also added baseline depressive symptoms as a covariate in all models and sensitised them with additional baseline predictors of PTSD symptoms as covariates. Although these approaches are robust methodologies for mitigating the effect of missingness, they can be insufficient with large attrition rates like in this study (Siddique et al., Citation2008).

Using unvalidated, self-reported, close-ended, dichotomous questions to explore side effects and post-trauma behaviours without assessing them at T0 may have impacted the precision of our estimations. Further research examining these phenomena should use validated instruments with adequate baseline assessments.

Furthermore, although we used PsyEd as an APC to control the unspecific ingredients of PFA, the duration of both interventions differed. Hence, we cannot discard that the significant effect of PFA on PTSD follow-up scores and other exploratory outcomes is explained by the increased duration of the intervention and no one or more specific factors. Further research will be needed to learn if any effect of PFA is the result of unspecific factors or one or more active components.

It is essential to acknowledge that the external validity of our results is limited by the characteristics of the sample, providers, delivery format, and model of PFA investigated. Our sample did not include trauma survivors of war, disasters, school crises (Brymer et al., Citation2012), occupational crises (Reynolds & Wagner, Citation2007), or children and adolescents. Additionally, our providers were psychology students who received eight hours of PFA training. So, it is still being determined if our results can be generalisable to layperson providers who may require more extensive instruction (Horn et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, our assessment only focused on one of many models of PFA (Ni et al., Citation2023), so the generalizability of our results to other protocols requires further investigation. Finally, the validity of our results in digitally delivered PFA cannot be ensured (Frankova et al., Citation2022).

This study’s strengths include a randomised controlled design with APC, participants and telephone operators blind to allocation, and using the same providers, written material, and places to provide PFA and PsyEd. These characteristics may have helped to reduce the effect of baseline imbalance, control the nonspecific effects of the intervention, and mitigate the allegiance effect. Furthermore, the rigorous registry of delivered components addresses a significant limitation in PFA literature: the lack of consistent documentation of the intervention components provided (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023). This information is crucial for understanding PFA mechanisms of action.

In conclusion, our results do not support the notion that PFA is effective for decreasing PTSD or depressive symptoms three months post-intervention. However, as we found a significant dose–response effect, it is possible that contamination could have obscured the distinction between the experimental and control conditions. PFA seems to be a safe intervention with promising effects on avoiding increased post-trauma alcohol/substance consumption, interpersonal conflicts, use of psychotropics, and use of sick leave. Important limitations, however, warrant cautious consideration of our results. As a significant burden of trauma is mediated by post-trauma problematic behaviours that can be independent of PTSD or depression symptomatology (Beck et al., Citation2009; Cerdá et al., Citation2011; Kartha et al., Citation2008), modifying post-trauma behaviour should be a clinically valuable goal by itself, even if not accompanied by a reduction of PTSD or depressive symptoms. Notably, given that PFA is a brief, single-session intervention, its capacity to produce large-scale effects might be inherently limited. However, the minimal effort and time required to implement PFA make it a highly feasible option. Consequently, even modest benefits derived from PFA should be considered valuable, given its ease of implementation.

Further research should explore the effect of delivering more PFA sessions in high-risk survivors, avoiding contamination and attrition, and using validated instruments to assess post-trauma behaviours with comparable baseline assessments. Exploring the effect of PFA in other settings and with other sample characteristics, protocols, providers, and delivery formats is crucial. Furthermore, expanding the scope of outcomes beyond diagnoses prevention or symptom control, adding early intervention’s effect on enhancing adaptive coping and modifying post-trauma behaviours, is urgent.

Consort.pdf

Download PDF (323 KB)Acknowledgements

To Hospital Dr. Sótero del Río and Hospital del Trabajador de Santiago, where this study took place.

Disclosure statement

Rodrigo Andrés Figueroa, Paula Francisca Cortés, and Humberto Marín are paid for teaching in the “Psychological First Aid ABCDE certification workshop” at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile School of Medicine. “PAP-ABCDE” is a trademark of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Data availability statement

The database and scripts used in this study can be downloaded from https://osf.io/s5wr8/?view_only=04b77e879d0049e0b7d215e3c69f386e. DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/S5WR8

.Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association.

- Amstadter, A. B., & Vernon, L. L. (2008). A preliminary examination of thought suppression, emotion regulation, and coping in a trauma exposed sample. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 17(3), 279–295. doi:10.1080/10926770802403236

- Bae, D., Matthews, J. J. L., Chen, J. J., & Mah, L. (2021). Increased exhalation to inhalation ratio during breathing enhances high-frequency heart rate variability in healthy adults. Psychophysiology, 58(11), e13905. doi:10.1111/psyp.13905

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-II. Beck depression inventory-second edition. Manual. The Psychological Corporation.

- Beck, J. G., Grant, D. M., Clapp, J. D., & Palyo, S. A. (2009). Understanding the interpersonal impact of trauma: Contributions of PTSD and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(4), 443–450. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.09.001

- Bisson, J. I., & Lewis, C. (2009). Systematic review of psychological first aid. Commissioned by World Health Organization. Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales; and World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Bobes, J., Calcedo-Barba, A., García, M., François, M., Rico-Villademoros, F., González, M. P., Bascarán, M. T., Bousoño, M., & Grupo Espanol de Trabajo para el Estudio del Trastornostres Postraumático. (2000). Evaluaciónde las propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de cinco cuestionarios para la evaluación del trastorno de estrés postraumático. Actas Especialidad Psiquiatría, 28, 207–218.

- Bodie, G. D., Vickery, A. J., Cannava, K., & Jones, S. M. (2015). The role of “active listening” in informal helping conversations: Impact on perceptions of listener helpfulness, sensitivity, and supportiveness and discloser emotional improvement. Western Journal of Communication, 79(2), 151–173. doi:10.1080/10570314.2014.943429

- Bowles, D. C., Butler, C. D., & Morisetti, N. (2015). Climate change, conflict and health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(10), 390–395. doi:10.1177/0141076815603234

- Brooks, S. K., Weston, D., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2021). Effectiveness and acceptability of brief psychoeducational interventions after potentially traumatic events: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1923110. doi:10.1080/20008198.2021.1923110

- Brymer, M., Jacobs, A., Layne, C., Pynoos, R., Ruzek, J., Steinberg, A., Vernberg, E., & Watson, P. (2012). Psychological first aid for schools: Field operations guide. National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

- Cerdá, M., Tracy, M., & Galea, S. (2011). A prospective population based study of changes in alcohol use and binge drinking after a mass traumatic event. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1-2), 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.011

- Cortés Montenegro, P. C., & Figueroa Cabello, R. F. (2019). ABCDE Psychological first aid application handbook: For individual and collective crises | PreventionWeb. https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/abcde-psychological-first-aid-application-handbook-individual-and-collective-crises.

- Escalona, R., Tupler, L. A., Saur, C. D., Krishnan, K. R. R., & Davidson, J. R. T. (1997). Screening for trauma history on an inpatient affective-disorders unit: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10, 299–305.

- Figueroa, R. A., Cortés, P. F., Marín, H., Vergés, A., Gillibrand, R., & Repetto, P. (2022). The ABCDE psychological first aid intervention decreases early PTSD symptoms but does not prevent it: Results of a randomized-controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2031829. doi:10.1080/20008198.2022.2031829

- Frankova, I., Vermetten, E., Shalev, A. Y., Sijbrandij, M., Holmes, E. A., Ursano, R., Schmidt, U., & Zohar, J. (2022). Digital psychological first aid for Ukraine. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(7), e33. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00147-X

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008

- Hardt, J., Herke, M., & Leonhart, R. (2012). Auxiliary variables in multiple imputation in regression with missing X: A warning against including too many in small sample research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 184. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-184

- Hawn, S. E., Cusack, S. E., & Amstadter, A. B. (2020). A systematic review of the self-medication hypothesis in the context of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid problematic alcohol Use. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(5), 699–708. doi:10.1002/jts.22521

- Hermosilla, S., Forthal, S., Sadowska, K., Magill, E. B., Watson, P., & Pike, K. M. (2023). We need to build the evidence: A systematic review of psychological first aid on mental health and well-being. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 36(1), 5–16. doi:10.1002/jts.22888

- Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., Friedman, M., Gersons, B. P., de Jong, J. T., Layne, C. M., Maguen, S., Neria, Y., Norwood, A. E., Pynoos, R. S., Reissman, D., Ruzek, J. I., Shalev, A. Y., Solomon, Z., & Steinberg, A. M. (2007). Ursano RJ five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry, 70(4), 283–315. discussion 316. doi:10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283

- Horn, R., O'May, F., Esliker, R., Gwaikolo, W., Woensdregt, L., Ruttenberg, L., & Ager, A. (2019). The myth of the 1-day training: The effectiveness of psychosocial support capacity-building during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Global Mental Health, 6, e5. doi:10.1017/gmh.2019.2

- IFRC Reference Centre for Psychosocial Support. (2018). A guide to psychological first aid for red cross and red crescent societies.

- Kahan, B. C., Jairath, V., Doré, C. J., & Morris, T. P. (2014). The risks and rewards of covariate adjustment in randomized trials: An assessment of 12 outcomes from 8 studies. Trials, 15, 139.

- Kartha, A., Brower, V., Saitz, R., Samet, J. H., Keane, T. M., & Liebschutz, J. (2008). The impact of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder on healthcare utilization among primary care patients. Medical Care, 46(4), 388–393. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc5d2

- Kessler, R. C. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 5), 4–12. discussion 13.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Levinson, D., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

- Laursen, D. R., Hansen, C., Paludan-Müller, A. S., & Hróbjartsson, A. (2020). Active placebo versus standard placebo control interventions in pharmacological randomised trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000055

- Ma, X., Yue, Z.-Q., Gong, Z.-Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N.-Y., Shi, Y.-T., Wei, G.-X., & Li, Y.-F. (2017). The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 874. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874

- Magill, N., Knight, R., McCrone, P., Ismail, K., & Landau, S. (2019). A scoping review of the problems and solutions associated with contamination in trials of complex interventions in mental health. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(4), 1–13.

- Marmar, C. M., Weiss, D. S., & Metzler, T. J. (1997). The peritraumatic dissociative experiences questionnaire. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 412–428). The Guilford Press.

- Marshall, G. N., & Orlando, M. (2002). Acculturation and peritraumatic dissociation in young adult latino survivors of community violence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 166–174. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.166

- Marshall, G. N., Orlando, M., Jaycox, L. H., Foy, D. W., & Belzberg, H. (2002). Development and validation of a modified version of the peritraumatic dissociative experiences questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 14(2), 123–134. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.2.123

- McCart, M. R., Chapman, J. E., Zajac, K., & Rheingold, A. A. (2020). Community-based randomized controlled trial of psychological first aid with crime victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(8), 681–695. doi:10.1037/ccp0000588

- Melipillán Araneda, R., Cova Solar, F., Rincón González, P., & Valdivia Peralta, M. (2008). Propiedades psicométricas del inventario de depresión de beck-II en adolescentes chilenos. Terapia Psicológica, 26(1). doi:10.4067/S0718-48082008000100005

- Ni, C.-F., Lundblad, R., Dykeman, C., Bolante, R., & Łabuński, W. (2023). Content analysis of psychological first aid training manuals via topic modelling. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2230110. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2230110

- No authors. (2010). mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in Non-specialized health settings: Mental health Gap action programme (mhGAP). World Health Organization.

- Oberg, A. L., & Mahoney, D. W. (2007). Linear mixed effects models. Methods Mol. Biol, 404, 213–234. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-530-5_11

- Pagoto, S. L., McDermott, M. M., Reed, G., Greenland, P., Mazor, K. M., Ockene, J. K., Whited, M., Schneider, K., Appelhans, B., Leung, K., Merriam, P., & Ockene, I. (2013). Can attention control conditions have detrimental effects on behavioral medicine randomized trials? Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(2), 137–143. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182765dd2

- Popp, L., & Schneider, S. (2015). Attention placebo control in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions: Theory and practice. Trials, 16, 150.

- Ramos, N., Morgado, D., Vivanco, C., Spencer, R., & Maia, Â. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ) in a sample of Chilean firefighters. Traumatology, 29, 493–503. doi:10.1037/trm0000400

- Reynolds, C. A., & Wagner, S. L. (2007). Stress and first responders: The need for a multidimensional approach to stress management. International Journal of Disability Management, 2(2), 27–36. doi:10.1375/jdmr.2.2.27

- Sahar, T., Shalev, A. Y., & Porges, S. W. (2001). Vagal modulation of responses to mental challenge in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 49(7), 637–643. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01045-3

- Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2007). Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. International Journal of Psychology, 42(4), 243–252. doi:10.1080/00207590701396641

- Shultz, J. M., & Forbes, D. (2014). Psychological first Aid: Rapid proliferation and the search for evidence. Disaster Health, 2(1), 3–12. doi:10.4161/dish.26006

- Siddique, J., Brown, C. H., Hedeker, D., Duan, N., Gibbons, R. D., Miranda, J., & Lavori, P. W. (2008). Missing data in longitudinal trials - part B, analytic issues. Psychiatric Annals, 38(12), 793–801. doi:10.3928/00485713-20081201-09

- Street, L. L., & Luoma, J. B. (2002). Control groups in psychosocial intervention research: Ethical and methodological issues. Ethics & Behavior, 12(1), 1–30. doi:10.1207/S15327019EB1201_1

- Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective With emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(3), 236–255. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

- van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67.

- Vera-Villarroel, P., Zych, I., Celis-Atenas, K., Córdova-Rubio, N., & Buela-Casal, G. (2011). Chilean validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C) after the earthquake on February 27, 2010. Psychological Reports, 109(1), 47–58. doi:10.2466/02.13.15.17.PR0.109.4.47-58

- Vernberg, E. M., Steinberg, A. M., Jacobs, A. K., Brymer, M. J., Watson, P. J., Osofsky, J. D., Layne, C. M., Pynoos, R. S., & Ruzek, J. I. (2008). Innovations in disaster mental health: Psychological first aid. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(4), 381–388. doi:10.1037/a0012663

- Wang, L., Norman, I., Edleston, V., Oyo, C., & Leamy, M. (2024). The effectiveness and implementation of psychological first aid as a therapeutic intervention after trauma: An integrative review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15248380231221492. doi:10.1177/15248380231221492

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D. S., Huska, J. A., & Keane, T. M. (1993). The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

- World Health Organization. (1997). The World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview 12-months version 2.1.

- World Health Organization, World Trauma Foundation & World Vision International. (2011). Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers.

- Worthington, M. A., Mandavia, A., & Richardson-Vejlgaard, R. (2020). Prospective prediction of PTSD diagnosis in a nationally representative sample using machine learning. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 532. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02933-1