ABSTRACT

Background: Police officers encounter various potentially traumatic events (PTEs) and may be compelled to engage in actions that contradict their moral codes. Consequently, they are at risk to develop symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), but also moral stress or moral injury (MI). To date, MI in police officers has received limited attention.

Objective: The present study sought to identify classes of MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms among police officers exposed to PTEs, while also investigating potential clinical differences between these classes.

Method: For this study, 421 trauma-exposed police officers were assessed on demographics and several clinical measurements including MI appraisals (self-directed and other-directed), PTSD severity, and general psychopathology. Latent class and regression analyses were conducted to examine the presence of different classes among trauma-exposed police officers and class differentiation in terms of demographics, general psychopathology, PTSD severity, mistrust, guilt, self-punishment, and feelings of worthlessness.

Results: The following five classes were identified: (1) a ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ (28%), (2) a ‘High MI, low PTSD class’ (11%), (3) a ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ (17%), (4) a ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’ (16%), and (5) a ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ (27%). There were significant differences between the classes in terms of age, general psychopathology, PTSD severity, mistrust, guilt, and self-punishment but no differences for gender and feelings of worthlessness.

Conclusion: In conclusion, we identified five classes, each exhibiting unique patterns of cognitive MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms. This underscores the criticality of measuring and identifying MI in this particular group, as it allows for tailored treatment interventions.

HIGHLIGHTS

This study identified classes differing in terms of endorsement of MI appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among police officers exposed to potentially traumatic events.

Five classes were identified, each exhibiting unique patterns of MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms.

It is important to measure the presence of MI appraisals in addition to PTSD symptoms in traumatized police officers as it can inform treatment interventions.

Antecedentes: Los oficiales de policía se enfrentan a diversos eventos potencialmente traumáticos (PTEs en su sigla en inglés) y pueden verse obligados a realizar acciones que contradicen sus códigos morales. En consecuencia, corren el riesgo de desarrollar síntomas de trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), pero también estrés moral o daño moral (MI en su sigla en inglés). Hasta la fecha, el MI en oficiales de policía ha recibido una atención limitada.

Objetivo: El presente estudio buscó identificar las clases de evaluaciones de MI y de síntomas de TEPT entre oficiales de policía expuestos a PTEs, al mismo tiempo que investigar las posibles diferencias clínicas entre estas clases.

Método: Para este estudio, 421 oficiales de policía expuestos a traumas fueron evaluados según sus datos demográficos y diferentes mediciones clínicas, incluidas las evaluaciones del MI (autodirigidas y dirigidas por otros), gravedad del TEPT, y psicopatología general. Se realizaron análisis de clases latentes y de regresión para examinar la presencia de diferentes clases entre los oficiales de policía expuestos a traumas y la diferenciación de las clases en términos demográficos, psicopatología general, gravedad del TEPT, desconfianza, culpa, autocastigo, y sentimientos de inutilidad.

Resultados: Se identificaron las siguientes cinco clases: (1) una ‘clase de MI bajo y TEPT alto’ (28%), (2) una ‘clase de MI alto y TEPT bajo’ (11%), (3) una ‘clase de MI alto y TEPT alto’ (17%), (4) una ‘clase de MI bajo y TEPT bajo’ (16%) y (5) una ‘clase de MI-otros alto y TEPT alto’ (27%). Hubo diferencias significativas entre las clases en términos de edad, psicopatología general, gravedad del TEPT, desconfianza, culpa y autocastigo, pero no hubo diferencias en cuanto a género y sentimientos de inutilidad.

Conclusión: En conclusión, identificamos cinco clases, cada una de las cuales exhibe patrones únicos de las evaluaciones cognitivas del MI y los síntomas de TEPT. Esto subraya la importancia de medir e identificar el MI en este grupo en particular, ya que permite intervenciones de tratamiento personalizadas.

1. Introduction

Repeated exposure to work-related potentially traumatic events (PTEs) is part of reality of many police officers. Physical violence, handling human remains, responding to abused children, motor vehicle crashes, and witnessing violent deaths are described as critical incidents in the work of police officers (Frankfurt et al., Citation2017; Weiss et al., Citation2010). Besides the emotional and physical challenges, police officers may also face moral decisions that potentially transgress important moral codes; examples are situations requiring decisions about the use of excessive force or violence against civilians or perpetrators, that may result in severe injury or even death (Komarovskaya et al., Citation2011). Facing these critical incidents may not only result in traumatic distress but also in moral distress (Blumberg et al., Citation2020) and ultimately result in moral injury (MI). Moral injury refers to the psychological impact after ‘perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to actions that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’ (Litz et al., Citation2009, p. 398). Different potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) can result in moral distress or MI in police officers. Examples are situations in which their course of action deviates from their moral values (e.g., being unable to assist individuals in need) or in which they witness colleagues engaging in morally inappropriate behaviour (Blumberg et al., Citation2020). Also, making mistakes during duty and experiencing conflict between supervisors’ orders and personal beliefs can induce moral distress (Blumberg et al., Citation2020). Research showed that making a mistake that resulted in the death of a colleague was considered the most stressful PTE commonly experienced by officers (Chopko et al., Citation2015; Weiss et al., Citation2010). In police officers, exposure to PMIEs has been found to be significantly related to compassion fatigue, symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Papazoglou et al., Citation2020), and other mental disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder and panic disorder) (Andersen & Papazoglou, Citation2015).

Notably, the appraisal of a PMIE and the violation of moral values is heavily influenced by cultural, contextual, and personal factors (Jinkerson, Citation2016). As a result, substantial variations exist among individuals in their responses to PMIEs and the subsequent impact on their mental health. Cognitive appraisals assigned to PMIEs play a crucial role in shaping the experience of traumatic events in general (Ehlers & Clark, Citation2000) and PMIEs in particular (Hoffman et al., Citation2018). PMIEs can be cognitive appraised in at least three ways: one can be troubled by the immoral actions of others (MI-other appraisals), the immoral actions of oneself (MI-self appraisals), or both (Hoffman et al., Citation2018; Hoffman et al., Citation2019). These diverse cognitive appraisals may yield different psychological reactions. For instance, increased MI-other appraisals have been found to be associated with elevated PTSD symptoms whereas increased MI-self appraisals were found to be associated with less intrusive memories (Currier, Foster, et al., Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2018). To explain this latter finding, it has been hypothesized that MI-self appraisals could be associated with a higher perception of control, reducing fear and subsequent PTSD symptoms (Hoffman et al., Citation2018). Both MI-self and MI-other appraisals were associated with feelings of depression in several studies (Bryan et al., Citation2016; Currier, Foster, et al., Citation2019; Hoffman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, studies showed that MI-self appraisals are related to internalizing emotions such as shame, guilt, and self-blame, whereas MI-other appraisals are associated with externalizing symptoms such as anger and frustration (Litz et al., Citation2018; Litz & Kerig, Citation2019; Schorr et al., Citation2018; Stein et al., Citation2012).

To date, limited research has explored individual differences in how police officers respond to PMIEs. Several studies have used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify subgroups or classes. LCA is a person-centred statistical method that allows for the examination of population heterogeneity by categorizing individuals into latent classes based on binary indicators of symptoms (Collins & Lanza, Citation2009). There are a few studies that applied LCA to data from occupational groups that are prone to PTSD or MI. For instance, one study on health and social care workers examined the exposure to PMIEs and identified three classes in this group: a ‘high exposure’ class, a ‘betrayal-only’ class, and a ‘minimal exposure’ class (Zerach & Levi-Belz, Citation2022). Another study on American veterans identified four classes based on their PMIE response patterns on the Moral Injury Events Scale (Nash et al., Citation2013): (1) high on all PMIEs; (2) witnessed transgressions; (3) troubled by failure to act; and (4) moderate on all PMIEs (Saba et al., Citation2022). As far as we are concerned, there is one study that identified different classes of police officers (and veterans) that included MI and showed different patterns of PTSD and symptoms associated with MI (e.g., shame, guilt, self-harm), although MI was not actually measured as such (Mensink et al., Citation2022). This suggests that, among police officers exposed to PMIEs, subgroups exist with varying combinations of symptoms of traumatic stress and MI related phenomena. Aside from the aforementioned study, there is a scarcity of research examining the heterogeneity in PTSD symptoms and MI appraisals among police officers. Yet, further investigating this issue is clinically relevant as it can ultimately improve treatment options for this vulnerable group. That is, trauma-focused therapy may suffice for individuals presenting high severity of PTSD symptoms without concurrent experiences of MI symptoms. On the other hand, individuals reporting PTSD symptoms combined with distress related to moral dilemmas may need additional interventions targeting MI and associated emotions of shame and guilt (Norman, Citation2022).

Accordingly, the primary objective of the present study was to examine the presence of subgroups among trauma-exposed police officers that differ in terms of PTSD and MI appraisals using LCA. Based on earlier studies (Mensink et al., Citation2022) we expected to find different classes of individuals; a class with individuals endorsing only PTSD symptoms, a class with individuals endorsing MI appraisals with no PTSD symptoms, a class with individuals endorsing MI appraisals (either MI-other or MI-self appraisals or a combination of both) and PTSD symptoms, and a class with low levels of PTSD symptoms and low levels of MI appraisals. Our second objective was to explore differences between emerging classes in terms of age, gender, general psychopathology, and PTSD severity. Also, it was examined if the classes differed in terms of the experience of feelings of worthlessness, mistrust, guilt, and self-punishment. We focused on these feelings considering they are related to MI symptoms in police officers (Mensink et al., Citation2022). Based on the literature, we expected to find differences in the presence of PTSD severity and psychopathology but no differences in terms of age or gender. More specifically, it was expected that individuals included in the class with elevated PTSD and MI appraisals would report the highest levels of PTSD symptoms and general psychopathology. Furthermore, so far no studies examined class differences in terms of worthlessness, guilt, mistrust of others, and self-punishment; therefore, this was examined exploratively. Yet, self-directed transgressions were associated with more feelings of guilt and shame in comparison to other-transgressions (Schorr et al., Citation2018; Stein et al., Citation2012). Therefore, it was expected that individuals in classes with relative high endorsement of MI-self appraisals (with low or high levels of PTSD symptoms) would evidence higher levels of guilt, worthlessness, and self-punishment in comparison to classes with lower levels of MI-self appraisals. Also, it was expected that individuals in classes with relative high endorsement of MI-other appraisals (with low or high levels of PTSD symptoms) would evidence higher scores on mistrust of others in comparison to classes with lower levels of MI-other appraisals.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

This study was conducted at ARQ Diagnostic Centrum (i.e., ARQ National Psychotrauma Centre), a Dutch centre for diagnostic assessment of people with trauma-related psychopathology. The assessment procedure includes administration of two clinician-rated interviews and self-report measures. Inclusion criteria for this study were: (a) over 18 years of age; (b) profession of (executive) police-officer; and (c) meeting the A-criterion for PTSD according to the CAPS-5. This study included 421 police officers who were subjected to assessment between August 2020 and May 2022. Data for this study were primarily collected for clinical purposes as part of the routine screening and assessment procedure. Subsequently, de-identified data were archived for scientific research purposes. All participants in this study were informed about the procedure and provided written informed consent for the utilization of their data for scientific purposes. At the assessment, in addition to the self-report questionnaires BSI and MIAS, the CAPS-5 interview was administered. This interview consisted of two parts; assessment of the traumatic event (criterion A) and the PTSD symptoms (criterion B – E). The interview was administered by trained psychologists. We examined the nature of the traumatic events by categorizing the descriptions of the A-criterion items. Clinicians conducted the CAPS-5 interview and therefore the descriptions in the participant files varied from a few words to an extended description of the event. Because of the large variation between clinicians in describing the A-criterion the categorization was not used for further analyses. The descriptions of the events were analysed using the steps of Thematic Analysis (TA) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). First, one researcher (NM) read the descriptions, then summarized each description in maximum five words (e.g., ‘fire in house’ or ‘murder on child’) and added this in a separate file. In case a participant reported multiple events, each event was summarized separately. Second, two researchers (NM and a research assistant) independently screened the summarized descriptions of the events and wrote down the common category that assembled the events. For instance, ‘fire in house’ was categorized as ‘fire’ and ‘murder on child’ as ‘murder’. Finally, the themes were discussed between NM and the research assistant and a coherent and logical categorization was made. The inter-rater reliability between the researchers was good (Cohen’s Kappa = .95, p < .001).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. PTSD symptoms

The Clinician-Administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is a 30-item structured diagnostic interview that measures the number of PTSD symptoms and PTSD severity (Weathers et al., Citation2018). In the first part of the interview, the traumatic event is assessed in order to check if the event meets the A-Criterion. The remaining items (Criteria B-E) are rated on a 5-point severity scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 4 (incapacitating). A sample item of criterion B is: ‘In the past month, have you had any unwanted memories of (event that meets the A-criterion) while you were awake, so not counting dreams?’. And follow-up questions were: ‘How much do these memories bother you?’ and ‘How often have you had these memories in the past month?’. The total score ranges between 0–80, with higher scores indicating more PTSD severity. The psychometric qualities of the CAPS-5 are good. Strong reliability and validity have been found in trauma-exposed samples (Boeschoten et al., Citation2018; Müller-Engelmann et al., Citation2020; Weathers et al., Citation2018). In the current sample, the total severity score demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .88).

2.2.2. Moral injury appraisals

The Moral Injury Appraisals Scale (MIAS) is a 9-item questionnaire that measures distress as a result of appraising immoral behaviours enacted by oneself with 4 items (MI-self) (e.g., ‘I am troubled because I did things that were morally wrong’) and others with 5 items (MI-Other) (e.g., ‘I am troubled by morally wrong things done by other people’). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert Scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). The internal consistency of this instrument in our sample was excellent (for the full scale the alpha was .90 and for MI-other and MI-self items, alphas were .90 and .92, respectively).

2.2.3. General psychopathology

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) is a 53-item self-report questionnaire (Derogatis & Melisaratos, Citation1983) that measures symptoms of psychological stress on nine subscales: depressive mood, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, somatization, psychoticism, suspicion, phobic fear, cognitive problems, and anxiety. Participants were asked to rate how much distress they experienced as a result of psychological symptoms during the past seven days on a five-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not at all’ to 4 = ‘extremely’). In this study we were interested in the relationship between four specific feelings (e.g., feelings of guilt, mistrust, self-punishment, and worthlessness) and class membership. To measure these feelings, four specific items of the BSI were used in the multinomial regression analyses: item 10 was used to measure mistrust (‘feeling that most people cannot be trusted’), item 34 was used to measure self-punishment (‘the idea that you should be punished for your sins’), item 50 to measure worthlessness (‘feelings of worthlessness’), and item 52 to measure guilt (‘feelings of guilt’). Researchers have found good psychometric properties of the instrument in the general population (de Beurs & Zitman, Citation2006). In the current sample, the α was .96.

2.3. Statistical analyses

All items of the MIAS and the CAPS-5 were recoded into dichotomous scores before they were included in the analysis. The CAPS-5 was recoded based on the standard scoring system of symptom endorsement (indicating the presence or absence of a PTSD symptom) (Weathers et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, symptoms were classified as present when they were rated as moderate, severe, or extreme (severity scores 2 until 4) and considered absent when rated as absent or mild (severity scores 0 and 1). A MIAS appraisal was classified as absent when items were rated as ‘not at all’ (score 1) or ‘a little’ (score 2) and classified as present when the items was rated as ‘somewhat’ (score 3) or ‘very much’ (score 4).

A LCA was performed in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2009) in which the allocation of group membership was based on most likely class membership. The one class model was fitted first, followed by models with increasing numbers of classes. In order to avoid local likelihood maxima in BLRT, 500 bootstrap samples were requested with 50 sets of starting values in the first and 20 in each bootstrap sample. The model fit for the classes were examined with the following indices: entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test, the adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-A), the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Sample-Size Adjusted BIC (SSA-BIC), and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). In order to avoid local likelihood maxima, 2,000 random sets of starting values in the first and 100 in the second step of optimization were requested. In addition, 200 initial stage iterations were used.

Lastly, it was investigated whether age, gender, PTSD severity, general psychopathology severity (BSI total score), and feelings of worthlessness, mistrust, guilt, and self-punishment (BSI item 10, 34, 50 and 52) differentiated between emerging latent classes. This was tested by conducting three independent multinomial logistic regression models in Mplus using the three-step procedure (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014). In order to check for possible interference between CAPS-5 and BSI items, separate multinomial regression models were estimated. Age in years and gender were included in a first model. General psychopathology and PTSD severity were included simultaneously in a second model. Lastly, the four BSI items were tested in a third model. A missing values analysis indicated less than 10% missing values for all responses and were handled with full maximum likelihood estimation and listwise deletion. Furthermore, a Little's Test for Data Missing Completely at Random (Little's MCAR Test) showed that the missing data were completely random, X2 = 118.8, p = .12.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

The sample consisted of 421 participants with 70% males. The average years of employment was M = 21.31, SD = 11.22 years. Most participants (72%) met the criteria for PTSD according to the CAPS-5. All participant characteristics in this sample are described in . The qualitive analyses of the descriptions of the PTEs revealed twelve categories (see ). The most commonly reported PTE in our sample was witnessing victims of suicide or suicide attempts (17%), followed by road traffic accidents (14%), resuscitation (10%), finding a corpse (not in relation to suicide) (5%), shooting incidents (9%), and stabbing incidents (4%).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of demographic variables and clinical characteristics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of qualitative analysis of potentially traumatic events.

3.2. LCA

represents model fit statistics for the six models that we evaluated. Moving from a one class solution to a six class solution, the log-likelihood values increased and BIC values decreased. All solutions showed significant p-values for the LMR-A results except for the six-class solution and, therefore, no more class solutions were considered. All entropy values were ≥.92. The three-class solution yielded the highest entropy value (.94), however the BIC was lowest in the five-class solution. Parsimony and interpretability supported selection of the five-class model and, therefore, this model was retained.

Table 3. Goodness-of-fit indices for 6 profiles.

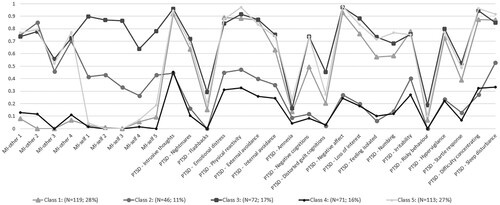

Based on other LCA studies (Forbes et al., Citation2015; Nickerson et al., Citation2014) a probability of ≥0.60 was considered as representing a high probability of item endorsement, values ≤0.59 and ≥0.16 as representing a moderate probability of endorsement, and values ≤0.15 as representing low probability of endorsement. Accordingly, the first class included 119 police officers (28%) with low endorsement of MI-other and MI-self items (0 of the 9 items) and moderate to high endorsement of 17 of the 20 PTSD items. This class was named the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’. The second class included 46 police officers (11%) with moderate endorsement of all five MI-self appraisals, moderate to high endorsement of all four MI-other appraisals, and low to moderate endorsement of 12 of the 20 PTSD items. This class was called the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’. The third class included 72 police officers (17%) evidencing high endorsement of all nine MI-other and MI-self items and high endorsement of all 20 PTSD items. This class was named the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’. The fourth class included 71 police officers (16%) with low endorsement of all nine MI-other and MI-self items and low endorsement of 11 of the 20 PTSD symptoms. This class was labelled as the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’. The final class included 113 police officers (27%) with high endorsement of all four MI-other items, low endorsement of four of the five MI-self items, and high endorsement of 19 of the 20 PTSD symptoms. This class was labelled as the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’. presents the symptom endorsement probability for the five-class solution.

3.3. Class membership differentiation

represents the descriptive statistics of the variables age, gender, PTSD severity (CAPS-5), and psychopathology severity (BSI) for the five classes. represent the results of the multinomial regression analysis. Instead of using only one class as a reference class to make the comparisons, we performed pairwise comparisons between all the classes. No significant differences between classes were found for gender but there were significant differences for age. Participants lower in age were more likely to be in the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ in comparison to the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’ and participants lower in age were more likely to be in the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’ in comparison to the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’. General psychopathology differentiated significantly between several classes. Participants with higher levels of general psychopathology were more likely to be in the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’, the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’, and the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ in comparison to the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ and the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’. In addition, participants with higher PTSD severity were more likely to be in the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’, the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’, and in the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ in comparison to the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’ and the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’. Lastly, differences between classes on four items of the BSI (item 10, 34, 50, and 52) were examined. There were no significant class differences for item 50 (‘feelings of worthlessness’). Participants with higher scores on item 10 (‘feeling that most people cannot be trusted’), were more likely to be included in the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ in comparison to the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’, the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’, and the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’. Also, participants with higher scores on this item were more likely to be in the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ than the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’. Participants with higher scores on item 34 (‘The idea that you should be punished for your sins’) were more likely to be included in the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ than the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ and the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’. Finally, participants with higher scores on item 52 (‘Feelings of guilt’) were more likely to be included in the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ than the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’ and participants with higher scores on this item were more likely to be in the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ than the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’, the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’, and the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the five-class solution.

Table 5. Summary of multinomial regression analyses with sociodemographic variables.

Table 6. Summary of multinomial regression analyses with PTSD severity and general psychopathology.

Table 7. Summary of multinomial regression analyses with four items of the BSI.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to identify classes differing in terms of endorsement of MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms among police officers exposed to PTEs. Additionally, it was investigated whether age in years, gender, general psychopathology, PTSD severity, and feelings relevant to MI differentiated between the latent classes. A model with five different classes appeared to be the best fitting and interpretable model: (1) a ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’; (2) a ‘High MI, low PTSD class’; (3) a ‘High MI, high PTSD class’; (4) a ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’; and (5) a ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’. These results are in line with other LCA studies in police officers and military people (Mensink et al., Citation2022) and, as such, provide further evidence that a substantial subgroup of trauma-exposed police officers are suffering from MI in addition to PTSD symptoms. Interestingly, there were three PTSD symptoms (e.g., flashbacks, amnesia, and risky behaviour) with relative low scores across all classes. This suggests that these symptoms may not discriminate well between subgroups with different patterns of PTSD symptoms and MI appraisals. Furthermore, it was shown that high levels of PTSD do not always co-occur with high levels of MI appraisals, or vice versa. This suggests that MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms are distinct constructs; it confirms the notion that MI has a unique phenomenology that is not accounted for by PTSD (Litz & Kerig, Citation2019).

The present investigation distinguished between MI-self and MI-other appraisals and identified a distinct group of individuals who endorsed particular MI-other appraisals (and not MI-self appraisals), along with high levels of PTSD. There was no class with only MI-self appraisals and PTSD symptoms. The differentiation between self-directed and other-directed MI appraisals adds to the existing studies on MI and suggests that police officers are less inclined to appraise PMIEs in relation to themselves. There are different explanations for this finding. First, it may be challenging to report incidents in which someone violated important moral codes or failed to prevent harm to others, due to potential feelings of shame and guilt. The participants in this study completed the questionnaires with the understanding that a clinician would discuss the results during the assessment. This may have caused hesitance to endorse MI-self appraisal items. Another possible reason why police officers may be less inclined to appraise PMIEs in relation to themselves is that being faced with moral transgressions can be perceived as inevitable ‘part of the job’. Because of that, the attribution of a PMIE to oneself may be limited to a specific selection of traumatic events. For instance, it could be more likely that the inability to aid a colleague who is physically assaulted or the inability to save someone's life during resuscitation may result in self-inflicting cognitive appraisals than witnessing a shooting accident in which the police officer attempts to arrest an offender. While this investigation briefly summarized the characteristics of the traumatic events, there was no systematic inquiry. Further research could investigate the relationship between MI and the nature of traumatic events in order to understand which events are more susceptible to cause MI.

Additionally, we examined a number of variables possibly associated with the five classes. No significant differences between classes were found for gender but participants in the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ and the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’ were younger. This contrasts with studies in healthcare professionals showing that a lower age correlated with higher MI scores (Mantri, Lawson, et al., Citation2021; Mantri, Song, et al., Citation2021) and one study in police officers that found no relationship between age and MI (Mensink et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that the p-value was close to the p < .05 threshold for statistical significance (p = .041) and due to multiple comparisons in the multinomial regression analyses, this result should be interpreted with caution. Next to PTSD symptoms, MI can be associated with a broad range of psychopathological symptoms. Participants in the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’, the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’, and the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ evidenced higher levels of general psychopathology in comparison to the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ and the ‘Low MI, low PTSD class’. The finding that the ‘High MI, low PTSD class’ evidenced higher levels of general psychopathology than the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’ is particularly notable because it suggests that MI appraisals (without PTSD) generate more psychological distress than PTSD symptoms alone. Other studies in refugees (Hoffman et al., Citation2019) and military groups (Currier et al., Citation2015; Nash et al., Citation2013) showed that experiencing MI adds additional burden on top of experiencing PTSD in terms of concurrent psychopathology. This highlights the importance of recognizing MI in police officers at an early stage during duty. Participants in the ‘Low MI, high PTSD class’, the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’, and the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ displayed higher levels of PTSD severity. This is in line with studies indicating that MI symptoms positively correlate with PTSD severity (Currier, McDermott, et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, participants in the ‘High MI-other, high PTSD class’ and the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ reported higher scores on the item ‘Feeling that most people cannot be trusted’ and the item ‘Feelings of guilt’. This underlines that feelings of guilt and distrust in others are particularly important for individuals who report both MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms. In addition, participants in the ‘High MI, high PTSD class’ reported higher scores on the item ‘The idea that you should be punished for your sins’. This implies that individuals who express notions of self-punishment, possibly extending to self-harm, are inclined to acknowledge both self-directed moral transgressions in addition to other-directed transgressions. While research exploring the link between self-directed and other-directed transgressions and self-punitive tendencies is lacking, it can be reasonably posited that self-directed transgressions might be intertwined with self-harming behaviours, as they threaten one's self-concept. Given the absence of a distinct class exclusively characterized by MI-self appraisals – with or without concurrent PTSD symptoms – the study was precluded from individually distinguishing MI-self from MI-other appraisals. To fully discern the nuances of self-directed and other-directed transgressions and their implications for clinical outcomes, future investigations are imperative.

Although this study is valuable in understanding how different groups of police officers react to PTEs, there are also several limitations. One limitation is that we primarily focused on cognitive appraisals, utilizing the MIAS, and had less focus on the wide spectrum of emotional processes related to MI such as regret, remorse, and shame. More research is necessary in order to understand if similar subgroups can be identified based on the emotional aspects of MI. Moreover, the descriptions of the traumatic events were derived from the CAPS-5 interview by different clinicians and lacking a clear instruction beforehand. As a result, the presence of PTEs and PMIEs was not measured systematically and the descriptions could not differentiate between PTEs and PMIEs. Nevertheless, the qualitative descriptions give more insight into the way police officers were exposed to trauma in this specific sample. Finally, this study did not provide information on when the reported traumatic experiences occurred. This consideration is notable as existing studies suggest that recent memories may be retrieved more vividly, accurately, and emotional intense compared to long-term events (Sutin & Robins, Citation2007), potentially exerting an effect on the outcomes of our results. Adjusting for temporal proximity to the traumatic event in the analyses would have enhanced the robustness of our findings and should be considered in future research.

In conclusion, MI appraisals emerge as a significant concern within the population of police officers. The findings of this study delineate five distinct subgroups, each exhibiting unique patterns of cognitive MI appraisals and PTSD symptoms. This underscores the importance of measuring and identifying MI in this particular group, as it can inform improvement of treatment interventions for police officers exposed to different types of PMIEs. While trauma-focused therapy may be adequate for certain individuals, others may require targeted interventions specifically addressing MI to attain optimal outcomes. The past years there is a growing number of treatment interventions targeting MI, such as Adaptive Disclosure (Litz et al., Citation2016), Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (Norman, Citation2022), or Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for moral trauma (BEP-MT) (de la Rie et al., Citation2021) and can be added to regular trauma focused therapies. Subsequent research endeavours should point out the potential requirement for distinct adaptations within MI treatment protocols, given that self- and other-transgressions may vary in their clinical outcomes.

Ethical approvement

After consultation, the medical ethics committee of Leiden stated that no ethical approval for the study was necessary since assessments were conducted primarily for diagnostic purposes within the institution. All participants in this study were informed about the procedure and provided written informed consent for the utilization of their data for scientific purposes. Participants were informed about the storage of their data and given the opportunity to have their data removed from the database.

Transparency and openness

This study was not preregistered. We reported how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, and all measures in the study. We do not have any previously published or currently in press works stemming from this dataset.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all police officers who participated in the study and the employees of the diagnostic centre who helped us by undertaking the assessments. In particular we thank Elizabeth Nolan for her assistance with the qualitative analyses and Niels van der Aa for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of the participants. Also, participants were not asked to give consent of saving their data in a public data repository. The MPlus output files are available at https://osf.io/6z92p/?view_only=3efc5baaf4b74bd7895dc303bed3b749.

References

- Andersen, J., & Papazoglou, K. (2015). Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among police officers: An understudied topic. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 17, 661–663. https://doi.org/10.4172/1522-4821.1000259

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Blumberg, D. M., Papazoglou, K., & Schlosser, M. D. (2020). Organizational solutions to the moral risks of policing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207461

- Boeschoten, M. A., Van der Aa, N., Bakker, A., Ter Heide, F. J. J., Hoofwijk, M. C., Jongedijk, R. A., Van Minnen, A., Elzinga, B. M., & Olff, M. (2018). Development and evaluation of the Dutch clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1546085. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1546085

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. O., Anestis, M. D., Anestis, J. C., Green, B. A., Etienne, N., Morrow, C. E., & Ray-Sannerud, B. (2016). Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment, 23(5), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115590855

- Chopko, B. A., Palmieri, P. A., & Adams, R. E. (2015). Critical incident history questionnaire replication: Frequency and severity of trauma exposure among officers from small and midsize police agencies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21996

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences, (Vol. 718). John Wiley & Sons.

- Currier, J. M., Foster, J. D., & Isaak, S. L. (2019). Moral injury and spiritual struggles in military veterans: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22378

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., & Malott, J. (2015). Moral injury, meaning making, and mental health in returning veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22134

- Currier, J. M., McDermott, R. C., Farnsworth, J. K., & Borges, L. M. (2019). Temporal associations between moral injury and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters in military veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 382–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22367

- de Beurs, E., & Zitman, F. G. (2006). De Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): De betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van een handzaam alternatief voor de SCL-90. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 61, 120–141.

- de la Rie, S. M., van Sint Fiet, A., Bos, J. B. A., Mooren, N., Smid, G., & Gersons, B. P. R. (2021). Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for Moral Trauma (BEP-MT): treatment protocol description and a case study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1929026. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929026

- Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700048017

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

- Forbes, D., Nickerson, A., Alkemade, N., Bryant, R. A., Creamer, M., Silove, D., McFarlane, A. C., Van Hooff, M., Fletcher, S. L., & O’Donnell, M. (2015). Longitudinal analysis of latent classes of psychopathology and patterns of class migration in survivors of severe injury. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(9), 1193–1199. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09075

- Frankfurt, S. B., Frazier, P., & Engdahl, B. (2017). Indirect relations between transgressive acts and general combat exposure and moral injury. Military Medicine, 182(11), e1950–e1956. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00062

- Hoffman, J., Liddell, B., Bryant, R. A., & Nickerson, A. (2018). The relationship between moral injury appraisals, trauma exposure, and mental health in refugees. Depression and Anxiety, 35(11), 1030–1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22787

- Hoffman, J., Liddell, B., Bryant, R. A., & Nickerson, A. (2019). A latent profile analysis of moral injury appraisals in refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1686805. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1686805

- Jinkerson, J. D. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000069

- Komarovskaya, I., Maguen, S., McCaslin, S. E., Metzler, T. J., Madan, A., Brown, A. D., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Henn-Haase, C., & Marmar, C. R. (2011). The impact of killing and injuring others on mental health symptoms among police officers. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(10), 1332–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.05.004

- Litz, B. T., Contractor, A. A., Rhodes, C., Dondanville, K. A., Jordan, A. H., Resick, P. A., Foa, E. B., Young-McCaughan, S., Mintz, J., Yarvis, J. S., & Peterson, A. L. (2018). Distinct trauma types in military service members seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22276

- Litz, B. T., & Kerig, P. K. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on moral injury: Conceptual challenges, methodological issues, and clinical applications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22405

- Litz, B. T., Lebowitz, L., Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2016). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. The Guilford Press.

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Mantri, S., Lawson, J. M., Wang, Z., & Koenig, H. G. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of moral injury symptoms in health care professionals. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 209(3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001277

- Mantri, S., Song, Y. K., Lawson, J. M., Berger, E. J., & Koenig, H. G. (2021). Moral injury and burnout in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 209(10), 720–726. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001367

- Mensink, B., van Schagen, A., van der Aa, N., & Ter Heide, F. J. J. (2022). Moral injury in trauma-exposed, treatment-seeking police officers and military veterans: Latent class analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 904659. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.904659

- Müller-Engelmann, M., Schnyder, U., Dittmann, C., Priebe, K., Bohus, M., Thome, J., Pfaltz, M. C., & Steil, R. (2020). Psychometric properties and factor structure of the German version of the clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5. Assessment, 27(6), 1128–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118774840

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2009). Statistical analysis with latent variables. Mplus User’s guide, 1998–2012.

- Nash, W. P., Marino Carper, T. L., Mills, M. A., Au, T., Goldsmith, A., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Military Medicine, 178(6), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Nickerson, A., Liddell, B. J., Maccallum, F., Steel, Z., Silove, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder and prolonged grief in refugees exposed to trauma and loss. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-106

- Norman, S. (2022). Trauma-Informed guilt reduction therapy: Overview of the treatment and research. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 9(3), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-022-00261-7

- Papazoglou, K., Blumberg, D. M., Chiongbian, V. B., Tuttle, B. M., Kamkar, K., Chopko, B., Milliard, B., Aukhojee, P., & Koskelainen, M. (2020). The role of moral injury in PTSD among law enforcement officers: A brief report. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 310. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00310

- Saba, S. K., Davis, J. P., Lee, D. S., Castro, C. A., & Pedersen, E. R. (2022). Moral injury events and behavioral health outcomes among American veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 90, 102605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102605

- Schorr, Y., Stein, N. R., Maguen, S., Barnes, J. B., Bosch, J., & Litz, B. T. (2018). Sources of moral injury among war veterans: A qualitative evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(12), 2203–2218. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22660

- Stein, N. R., Mills, M. A., Arditte, K., Mendoza, C., Borah, A. M., Resick, P. A., Litz, B. T., Belinfante, K., Borah, E. V., Cooney, J. A., Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., Kippie, A., Lester, K., Malach, S. L., McClure, J., Peterson, A. L., Vargas, V., & Wright, E. (2012). A scheme for categorizing traumatic military events. Behavior Modification, 36(6), 787–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445512446945

- Sutin, A. R., & Robins, R. W. (2007). Phenomenology of autobiographical memories: The memory experiences questionnaire. Memory (Hove, England), 15(4), 390–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701256654

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000486

- Weiss, D. S., Brunet, A., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Liberman, A., Pole, N., Fagan, J. A., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). Frequency and severity approaches to indexing exposure to trauma: The Critical Incident History Questionnaire for police officers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 734–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20576

- Zerach, G., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2022). Moral injury, PTSD, and complex PTSD among Israeli health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of self-criticism. Psychological Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001210