ABSTRACT

Background: Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have negative impacts on women with children, including psychosocial and general health problems. However, there is limited research investigating ACEs identifying the characteristics of distinct subgroups according to the frequency of ACEs.

Objective: Utilizing the national dataset of the Family with Children Life Experience 2017, this study aimed to classify patterns of ACEs based on the total number of types of ACEs and the types of predominant events, and to examine differences in general and psychological characteristics, as well as experiences of violence in adulthood among the classes identified.

Method: A total of 460 Korean mothers raising infants or toddlers participated. Latent class analysis was performed to classify the patterns of ACEs, while t-tests and Chi-square tests were used to examine differences in general and psychological characteristics and experiences of violence between the ACEs subgroups.

Results: The participants were classified into two subgroups: the ‘high-ACEs group’ and the ‘low-ACEs group’. The high-ACEs group exhibited higher rates of child abuse, workplace violence perpetration and victimization, as well as lower self-esteem, higher depression levels, and increased suicidal thoughts compared to those of the low-ACEs group.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the significant role of ACEs on the formation of an individual’s psychological characteristics and their propensity to experience additional violence even into adulthood, as perpetrators and as victims. It is noteworthy how the influence of ACEs extends across generations through child abuse. These findings offer insights for developing interventions aimed at mitigating the negative effects of experiences of violence on mothers raising young children.

HIGHLIGHTS

Two distinct subgroups were identified according to the frequency of ACEs: the ‘high-ACEs group’ and the ‘low-ACEs group’.

Compared to those of the low-ACEs group, the high-ACEs group presented higher rates of child abuse, workplace violence perpetration and victimization, lower self-esteem, higher depression levels, and increased suicidal thoughts.

The low self-esteem induced by ACEs may contribute to the amplification of psychological vulnerabilities and the occurrence of additional violent experiences even in adulthood.

Antecedentes: Las experiencias adversas en la infancia (ACEs, por sus siglas en inglés) tienen impactos negativos en las mujeres con hijos, incluyendo problemas psicosociales y de salud general. Sin embargo, hay estudios limitados que investiguen las ACEs que identifiquen las características de distintos subgrupos según la frecuencia de las ACEs.

Objetivo: Utilizando la base de datos nacional de Experiencias de vida de Familias con niños 2017, este estudio tuvo como objetivo clasificar los patrones de ACEs basándose en el número total de tipos de ACEs y los tipos de eventos predominantes, examinando las diferencias en las características generales y psicológicas, así como las experiencias de violencia en la adultez entre las clases identificadas.

Método: Un total de 460 madres coreanas que crían a bebes o niños pequeños participaron en el estudio. Se realizó un análisis de clases latentes para clasificar los patrones de ACEs.

Resultados: Las participantes fueron clasificados en dos subgrupos: el ‘grupo de ACEs de alto nivel’ y el ‘grupo de ACEs de bajo nivel’. El grupo de ACEs de alto nivel mostró tasas más elevadas de abuso infantil, perpetración y victimización en el lugar de trabajo, así como menor autoestima, mayores niveles de depresión y un aumento de pensamientos suicidas comparados con el grupo de ACEs de bajo nivel.

Conclusión: Los hallazgos destacan el papel significativo de las ACEs en la formación de las características psicológicas de un individuo y su propensión a experimentar violencia adicional incluso en la adultez, tanto como perpetradores como víctimas. Es notable cómo la influencia de las ACEs se extiende a través de las generaciones a través del abuso infantil. Estos hallazgos ofrecen perspectivas valiosas para desarrollar intervenciones orientadas a mitigar los efectos negativos de las experiencias de violencia en madres que crían a niños pequeños.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are defined as traumatic events experienced before adulthood, such as abuse, neglect, family dysfunction, or exposure to neighbourhood violence. An early ACEs study conducted by Felitti et al. (Citation1998) reported that ACEs had cumulative negative effects on an individual’s health including an increased risk of various diseases and leading causes of death, which involves alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, smoking, obesity, ischaemic heart diseases, cancer, and lung diseases. Since then, many studies have demonstrated a linkage between ACEs and negative health outcomes, with the degree of influence varying according to the number of accumulated ACEs (Anda et al., Citation2008, Citation2010). ACEs are associated with a variety of physical and psychological problems throughout an individual’s life course. Through a process of biological embedding, also known as ‘allostasis’, in which the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems are altered as stress levels increase, ACE results in changes in individual biological systems (Danese & McEwen, Citation2012). For instance, those with ACEs showed a smaller volume of the prefrontal cortex, greater activation of the HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal) axis and elevated levels of inflammation compared with those without ACEs (Danese & McEwen, Citation2012). For instance, studies have reported an 11% increase in the risk of diabetes for each additional ACE (Deschênes et al., Citation2018), and having more than four ACEs had an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease, stroke, and nearly double the risk of premature death (Bellis et al., Citation2015; Felitti et al., Citation1998). The prevalence of experiencing multiple ACEs is significant, with 78.9% of adults in South Korea (Ryu et al., Citation2017) having encountered more than one ACE.

ACEs are known to have diverse effects on women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the parenting journey. ACEs have been associated with increased pain during pregnancy (Drevin et al., Citation2015) and preterm birth (Christiaens et al., Citation2015). In addition, health risk behaviours such as smoking, which are related to ACEs, can have detrimental effects on both the well-being of pregnant women and the fetus (Leeners et al., Citation2006). The impact of ACEs on women in pregnancy is especially highlighted when it comes to depression. A higher frequency of ACEs was associated with a 4.2 times higher risk of depression in late pregnancy and postpartum when the ACEs score exceeded 5 compared to scores below 5 (Ångerud et al., Citation2018).

In addition, ACEs have a critical impact on women who are raising children, Mothers with ACEs are more likely to have chronic pain (Dennis et al., Citation2019), and also presented higher rates of substance use disorder (Smith et al., Citation2021). These findings highlight the impact of ACEs on both aspects of physical and psychological health. Especially when it comes to parenting, it becomes even more clear that ACEs play a significant part in the performance of the mother role. Mothers with ACEs reported high levels of postpartum parenting stress (Moe et al., Citation2018) and low parenting morale (McDonald et al., Citation2019). Specifically, infancy is a period characterized by dynamic and rapid development (Hockenberry & Wilson, Citation2013) that involves egocentric thought, stubbornness, and aggression. This can result in higher levels of parenting stress levels for mothers raising infants compared to mothers with children of other ages (Creasey & Reese, Citation1996). Considering that parenting during infancy is recognized as the most important predictor of cognitive development in children (Nievar et al., Citation2014), early detection and intervention of ACEs become highly important. Moreover, it is worth noting that the impact of ACEs on women with children is magnified by the fact that it can also be transmitted to their children across generations. For example, maternal ACEs were reported to be associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing problems via maternal attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Cooke et al., Citation2019). However, these previous findings have limitations in that they mostly reported the effects of ACEs in a whole regardless of the level of ACEs.

Despite the magnitude of the impact of ACEs, there is a lack of research that subdivides participant groups according to the level of exposure to ACEs, particularly among women raising children. As people usually hesitate to disclose or share their histories of ACEs with other people, there is a limit to finding out when it comes to ACEs and their characteristics. This makes it even more important to identify specific features of high-risk populations so that early interventions and preventive methods can be implemented. LCA is a research method to examine the heterogeneity and to identify the most mutually exclusive classes of adults with ACEs (Chen et al., Citation2022). It has increasingly been used to identify underlying subgroups of people who experience distinctive patterns of co-occurring ACEs (Wang et al., Citation2024). LCA has its strength over traditional statistical analysis methods, revealing specific ACE clusters that exert potent effects on certain outcomes (Wang et al., Citation2024). In this study, we aimed to classify patterns of ACEs based on the total number of types of ACEs and the types of predominant events (assessed via a self-report questionnaire) and to examine differences in general and psychological characteristics, as well as experiences of violence during adulthood, among the classes identified. In addition to looking at the number of ACEs, it was important to identify groups with different profiles since the effects of predominant events were also expected beside the ACEs score. It was presumed that certain types of ACEs that an individual was specifically highly exposed to may contribute to qualitative distinctiveness in the consequences of ACEs. To be more specific, there were two aspects in what was expected to be found regarding the categorization of distinctive groups, including the quantitative and qualitative aspects. In terms of the quantitative aspect, it was expected that by classifying the participants into several groups through LCA, it would be possible to specify the point where the degree of such association differs significantly. For this purpose, after ascertaining the number of types of ACEs, the participants were classified by the point where the number of types of ACEs differed significantly in their association with adult life. In addition, quantitative characteristics within the classified groups were expected to be discovered through distinctive gaps in the types of predominant events among the groups. LCA was utilized to help discover the heterogeneity of groups with different types of ACEs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This study utilized a secondary analysis of data from the Family with Children Life Experience 2017 dataset, conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) (KIHASA, Citation2017). The primary objective of this survey was to identify the prevalence of ACEs and analyse their impact on the physical and mental health as well as social relationships of Korean adults in their adulthood. The survey was conducted from August to September 2017, utilizing a stratified sampling approach based on the population distribution by region in South Korea. As of 2022, this was the most recently available dataset that was suitable for addressing the aims of this study. The data for analysis were obtained through the website of KIHASA Health and Welfare Data Portal (https://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/main.html), which is open to the public.

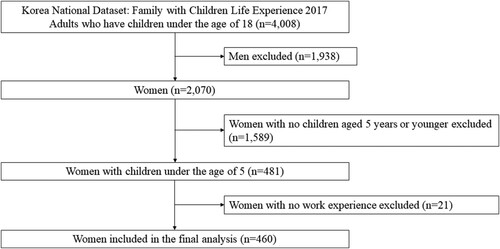

A total of 4008 adults with children under the age of 18 participated in the survey. For the purpose of the current study, men and women with no children aged 5 years or younger and women with no work experience were excluded. Considering that 6 years is the age at which young children enter elementary school in Korea, it was thought that there would be a significant difference between the child’s development level and the parenting burden of parents of children aged 5 years or older. Thus, women with children aged 5 years or younger were chosen as participants. Given the study’s aim of identifying the association between ACEs and workplace violence in adulthood, those without work experience were excluded. Having any experience in any kind of economic activity was considered as having had work experience. Finally, a total of 460 women were included in the analysis ().

This study was approved by the Review Board of Y University (Y-2023-1431). As a secondary data analysis, the informed consents of the participants were waived.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics included both general and psychological characteristics, as well as experiences of violence. General characteristics included mother’s age, primary caregiver status, current employment status, education level, overall health condition, high-risk drinking status, smoking status, monthly family income, family type, family formation, and living region. The primary caregiver could be either the mother or someone else. Current working status was divided into regular employee, irregular employee, self-employed worker, and housewife/others. Education level was categorized into high school or below, college, and university or higher. Overall health condition was rated as good or bad, and high-risk drinking and smoking were answered by a yes or no response. Family type was categorized as households with less than two generations and three generations or more. Family formation referred to households with infants and/or toddlers or households with infants and/or toddlers and preschoolers. Living region was categorized into a metropolis, a small city, or a rural area.

Psychological characteristics consisted of life satisfaction, suicidal thoughts, depression, self-esteem, social support, and parenting stress. Experiences of violence included child abuse, as well as perpetration and victimization of workplace violence. Life satisfaction was categorized as either satisfied or unsatisfied. Suicidal thoughts were answered by a yes or no response.

Measurement of psychological characteristics involved the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression scale (Radloff, Citation1977) for depression, the Self-esteem scale developed by Rosenberg (Citation1965) for self-esteem, and the Social Network scale by Lubben et al. (Citation2006) for social support. Cronbach’s α of each of the scales were .69, .83, and .82, respectively. Parenting stress was measured using items from the National Survey of Child Abuse 2011 (Ahn et al., Citation2011). To measure child abuse, a subset of items from the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus & Hamby, Citation1997) was used. Items for measuring workplace violence perpetration and victimization were developed by the researchers for the original survey. All the variables, with the exception of child abuse, were measured on Likert scales, while child abuse was quantified by the total number of abusive actions directed at their own child. Higher scores indicated higher levels of depression, self-esteem, social support, severe parenting stress, a greater number of child abuse experiences, and a higher incidence of workplace violence perpetration and victimization.

2.2.2. Adverse childhood experiences

ACEs were measured using the Korean version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 and revised by Ryu et al. (Citation2017). The questionnaire categorizes ACEs into 13 types, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, alcohol or drug abuse, family members with depression and mental disorders, admission to a mental hospital, family members with suicidal tendencies, family members who are exposed to violence, being orphaned or raised by a single parent, parental separation or divorce, emotional neglect, physical neglect, bullying, and exposure to community and communal violence (WHO, Citation2020). It also has used the classification of the 13 types into 6 domains, including the relationship with parents/guardians (neglect), family environment (household dysfunction), emotional/physical/sexual abuse, peer violence, witnessing community violence, and exposure to collective violence (WHO, Citation2020).

The total ACE score was calculated based on the number of ACEs reported by the participants. To be specific, exposure to a particular type of ACEs can be interpreted as a value of score 1, and the scores can add up as participants are exposed to multiple types of ACEs. Thus, higher score of ACEs questionnaire reflects participants’ exposure to more various types of ACEs. Cronbach’s α was .82 (WHO, Citation2020) at the time of development, and .81 in the current study.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). In addition, Mplus version 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to identify latent classes of adult women based on their ACE scores.

A latent class analysis (LCA) was performed to explore the differences in participant characteristics across latent classes determined by ACEs. LCA is a research method that categorizes ACE scores and identifies the probability of belonging to a specific class. It assumes that the entire group is composed of heterogeneous subgroups and presents the probability of individual experiences belonging to each subgroup. This approach enables the identification of high-risk groups and the characteristics of target groups that require priority intervention (Lanza & Rhoades, Citation2013).

To determine the optimal number of latent classes, various statistical criteria were considered, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC), entropy, the Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio Test (LMRT), the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) (Goodman, Citation1974), and the possibility of meaningful interpretation (Collins & Lanza, Citation2009). After classifying the appropriate latent classes, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine significant differences in ACEs among the latent classes. Additional t-tests and Chi-square tests were performed to identify differences in participant characteristics across the latent classes.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

presents the characteristics of the participants. The average age of the participants was 33.74 years (SD = 3.96). The mean score for parenting stress was 10.18 (SD = 3.440), ranging from 5 to 19. The mean score for child abuse was 0.38 (SD = 0.838), ranging from 0 to 8, while the mean score for workplace violence was 4.20 (SD = 0.770), ranging from 4 to 12.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 460).

presents the results of the ACEs of the participants. The mean score for relationships with parents/guardians was 0.97 (SD = 0.272), while the mean score for household dysfunction was 0.28 (SD = 0.478). In addition, the mean score for emotional/physical/sexual abuse was 0.41 (SD = 0.643), 0.28 (SD = 0.359) for peer violence, 0.25 (SD = 0.271) for witnessing community violence, and 0.01 (SD = 0.079) for exposure to collective violence.

Table 2. Results of adverse childhood experiences.

3.2. Identification of latent classes

LCA was conducted to identify the optimal number of latent classes for the participants based on their ACE scores and predominant events. shows the model fit indices for each latent class group. Taking into account all the statistical criteria and the possibility of meaningful interpretation, it was determined that a two-class model provided the best fit for the participants. Specifically, the p-value for LMRT indicated statistical significance for the two-class model, and no other values indicated any concerns regarding the statistical standards.

Table 3. Model fit indices for latent class groups of adverse childhood experiences.

presents the distribution of the mean scores for each subdomain of ACEs. For intra-group comparisons, the mean scores were significantly different for all subdomains (p < .001). Group 1 had lower ACE scores for all subdomains than Group 2, resulting in Group 1 being labelled as the ‘low-ACEs group’, consisting of 390 participants (84.8%), and Group 2 was labelled as the ‘high-ACEs group’, comprising 70 participants (15.2%). It was also found that the domains of ACEs that showed the most remarkable gaps between the two groups were emotional/physical/sexual abuse (t = −23.362, p < .001) and witnessing community violence (t = −12.554, p < .001). Thus, Group 1 comprises those with lower exposure in all domains, while Group 2 comprises those with predominant events in the domains of emotional/physical/sexual abuse and witnessing community violence.

Table 4. Differences in adverse childhood experiences between the latent class groups.

3.3. Differences in participant characteristics between the subgroups

presents the differences in participant characteristics based on the latent classes. Significant differences were found in age (t = 6.543, p = .011), current working status (χ2 = 6.112, p = .014), overall health condition (χ2 = 21.863, p < .001), life satisfaction (χ2 = 8.247, p = .004), suicidal thoughts (χ2 = 22.249, p < .001), depression (t = 14.010, p < .001), self-esteem (t = 6.361, p = .012), parenting stress (t = 21.664, p < .001), child abuse (t = 88.031, p < .001), victimization of workplace violence (t = 36.972, p < .001), and perpetration of workplace violence (t = 40.656, p < .001) between the two latent groups. To be specific, in terms of general characteristics, the mean age of the high-ACEs group was younger than that of the low-ACEs group, and the rates of participants evaluating their overall health condition as good of the high-ACEs group was lower than those of the low-ACEs group. For psychological characteristics, the participants in the high-ACEs group also reported lower life satisfaction, higher rates of suicidal thoughts, higher level of depression, lower level of self-esteem, and higher level of parenting stress. Lastly, the rates of child abuse and perpetration of workplace violence were higher in the high-ACEs group.

Table 5. Differences in participants’ characteristics between the latent class groups.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify latent classes of ACEs among a representative sample of Korean women who raise young children and compare participant characteristics between the identified groups. LCA was conducted in this study to categorize ACE scores and the types of predominant events, and to identify the probability of belonging to a specific class (Lanza & Rhoades, Citation2013). The key difference between the groups expected through LCA was the difference in general and psychological characteristics and experiences of violence during adulthood according to the number of types of ACEs. It was expected that the higher the number of types of ACEs, the more negatively it would affect adult life. It was also expected that by classifying the participants into several groups through LCA, it would be possible to specify the point where the degree of such association differs significantly. For this purpose, after ascertaining the number of types of ACEs, the participants were classified by the point where the number of types of ACEs differed significantly in their association with adult life. In addition, quantitative characteristics within the classified groups were expected to be discovered through distinctive gaps in the types of predominant events among the groups. Consequently, this study demonstrated that there are two distinct subgroups of ACEs (‘high’ versus ‘low’) and revealed significant differences in experiences of violence, including child abuse and workplace violence perpetration and victimization, between these groups.

Psychological characteristics such as self-esteem, depression, suicidal thoughts, and life satisfaction, as well as general characteristics such as age, current working status, and overall health condition, also exhibited significant variations between the subgroups. These findings highlight the negative impacts of ACEs on the psychological characteristics of mothers as it was shown in the overall adult population. Moreover, it was found that ACEs are associated with violence experiences in the adulthood, with a highlight on child abuse, which may work as a key path for the intergenerational transmission of ACEs.

Regarding experiences of violence, the high-ACEs group exhibited a higher rate of child abuse than the low-ACEs group. Previous research has indicated that mothers with ACEs tend to exhibit harsher parenting behaviours, leading to internalization and externalization problems in their children (Wolford et al., Citation2019). In addition, ACEs of mothers have an indirect effect on lower levels of positive parenting behaviour, with accumulated ACEs increasing the likelihood of child abuse within their own families (Greene et al., Citation2020). These findings align with the higher levels of parenting stress observed in the high-ACEs group. In general, ACEs have been positively associated with parenting stress while negatively affecting parenting competence (LaBrenz et al., Citation2020). In other words, the adversities and traumas experienced by parents during their own childhood can impact their parenting practices later in life (LaBrenz et al., Citation2020). It is possible that the high level of parenting stress in the high-ACEs group contributes to the increased occurrence of child abuse within that group. In this regard, addressing parenting stress and child abuse should be approached through simultaneous interventions rather than separate ones. Interventions targeting the parenting stress of mothers in the context of infants and toddlers should adopt diverse approaches considering the underlying causes of parenting stress. For example, social support and self-esteem have been suggested as mediating factors that need to be considered (Park & Chung, Citation2018). In addition, given that self-efficacy levels can predict child abuse, evaluating and addressing self-efficacy should be part of the intervention strategy (Jeon & Kim, Citation2019).

The high-ACEs group exhibited higher rates of workplace violence perpetration and victimization. It is well-known that different types of ACEs are often inter-related, and experiencing one ACE increases the risk of exposure to additional ACE (Dong et al., Citation2004; Thulin et al., Citation2021). The findings of the current study add up information that the close connection between each ACE remains even in the adulthood, supporting previous findings that ACEs are related to certain types of violence in adulthood, such as intimate partner violence (IPV) (Thulin et al., Citation2021). They are in line with the findings of Clemens et al. (Citation2023), who pointed out that ACEs were significant influencing factors for both perpetration and victimization of IPV in adulthood among Germans, and those of Lee et al. (Citation2021), who found that ACEs were associated with IPV perpetration among black men. Specifically, the findings are novel in that it revealed that ACEs are associated with the perpetration of violence in later life, not only victimization, implying that individuals who have experienced ACEs may struggle to break free from the cycle of violence, both as victims and as perpetrators.

Few studies have been found to examine the association between ACEs and adulthood violence through LCA, however, several studies on other aspects of consequences of ACEs in the adulthood have been reported. For example, from a study in which LCA was used to classify groups of participants with ACEs and the association of the classes and mental disorders in the adulthood through logistic analysis, it was reported that ‘child maltreatment’ class was more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Also, the ‘community violence’ class was more likely to have PTSD in their adulthood, compared to the ‘low adversity’ class (Lee et al., Citation2020). In another study, it was found that the childhood maltreatment and high adversity/community violence classes engaged in more risk-related behaviours (Parnes & Schwartz, Citation2022). In addition to such studies, the current study newly found that in terms of predominant events, the high-ACEs group, which is the group with higher scores in the domains of emotional/physical/sexual abuse and witnessing community violence, presented higher rates of child abuse and workplace violence perpetration and victimization. This not only supports the vicious cycle of past and future violence but also implies that violence perpetrated by adults rather than peers, whether direct or indirect, may have a stronger influence on future violence experience.

Regarding psychological characteristics, the prevalence of low self-esteem, depression, and suicidal thoughts were higher in the high-ACEs group compared to those of the low-ACEs group. These psychological characteristics are closely inter-related, with the possibility of low self-esteem being the starting point. Previous research on childhood abuse initially focused on identifying the negative effects on mental health, with particular emphasis on self-esteem and depression (Kang, Citation2017). It is commonly believed that the major source of negative effects caused by childhood abuse is derived from low self-esteem, leading to feelings of worthlessness (Kang, Citation2017). Likewise, ACEs may diminish self-esteem, which can serve as a potential risk factor for depression, and high levels of depression contribute to the emergence of suicidal thoughts. For instance, studies have reported a significant association between low self-esteem and child abuse, as well as its role as a risk factor for depression and anxiety (Shah et al., Citation2020). In addition, it has been reported that depression is the most prevalent negative manifestation of low self-esteem (Harris, Citation2001). Although low self-esteem is not classified as a disease, it can be a significant risk factor for other mental health difficulties. This highlights the importance of early detection and interventions for addressing negative thoughts or perceptions about oneself.

The high-ACEs group also exhibited a high rate of life dissatisfaction. In the current study, life satisfaction was measured by assessing overall satisfaction with life, work, health, and relationships with spouses and children. These findings are consistent with previous studies, as a large longitudinal study conducted in the United States reported significantly lower life satisfaction among individuals with ACEs compared to those without ACEs (Mosley-Johnson et al., Citation2019). In particular, the impact on life satisfaction was particularly significant among individuals with a history of abuse and family dysfunction (Mosley-Johnson et al., Citation2019). This could be attributed to the influence of ACEs on other demographic factors that contribute to subjective life satisfaction. For instance, sexual abuse experiences have been linked to a higher possibility of job dismissal in adulthood (Sansone et al., Citation2012). Another prospective cohort study (Currie & Spatz Widom, Citation2010) revealed that individuals with ACEs had lower levels of education, employment, income, and fewer assets in adulthood compared to matched control respondents without ACEs. When demographic characteristics were controlled, there was a 14% difference in employment probability in middle age between the ACEs group and the non-ACE group, with these effects being more pronounced in women (Currie & Spatz Widom, Citation2010). Future policies should incorporate a comprehensive approach that considers health and well-being, especially focusing on the needs of children and families, economic security, healthcare, workplace safety, and other community and system-related support mechanisms.

Differences in general characteristics, such as age, current working status, and overall health condition, were observed between the ACEs subgroups. The average age of the high-ACEs group was lower than that of the low-ACEs group. This finding suggests that increased awareness of child abuse, sexual harassment, and neglect in recent times may have led to a more sensitive recognition and reporting of ACEs among young respondents. A similar trend was observed in a study conducted in the United States, which reported a negative association between the number of ACEs and age (Jia & Lubetkin, Citation2020). However, there is a lack of research on the prevalence of ACEs among mothers of infants and toddlers, making it difficult to confirm prevalence trends by age.

Regarding current working status, the rate of non-working women was higher in the high-ACEs group than in the low-ACEs group. This supports previous findings that a history of multiple types of child abuse contributes to unemployment in adulthood (Sansone et al., Citation2012). Other studies found that individuals with a history of ACEs tend to have lower education levels, higher rates of unemployment, and a higher likelihood of living in poverty (Currie & Spatz Widom, Citation2010; Metzler et al., Citation2017). This suggests that ACEs may undermine an individual’s ability to obtain and maintain employment in adulthood (Topitzes et al., Citation2016). In other words, the impact of ACEs may extend beyond employment in adulthood and potentially limit opportunities throughout life.

The high-ACEs group had a higher rate of poor overall health condition compared to the low-ACEs group. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have established a relationship between ACEs and adult health outcomes. First, there is evidence of the negative impact of ACEs on objective health outcomes, such as disease prevalence. For example, studies have shown that individuals with ACEs are 36% more likely to experience adult obesity (Danese & Tan, Citation2014) and blood pressure levels have been reported to rise at a faster rate after the age of 30 (Su et al., Citation2015). In addition, ACEs have been significantly associated with a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreased high-density lipoprotein/ low-density lipoprotein ratio, increasing the risk of dyslipidemia (Spann et al., Citation2014), and nearly double the probability of early death in the presence of four or more ACEs (Bellis et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, ACEs are known to have negative impacts on subjective health status as well. Subjective health status can be affected by various cognitive variables, such as health-related self-efficacy and coping abilities, as well as objective health outcomes. For example, self-esteem and social support were reported to be strong predictors of subjective health, and individuals who exhibited good coping skills and received support reported significantly better health outcomes despite severe childhood violence (Jonzon & Lindblad, Citation2006). Therefore, it is crucial to examine the effect of ACEs on variables related to individuals’ health-related perceptions and attitudes and to understand the pathways leading to subjective health status.

Although the present study reveals important findings, it has some limitations. Firstly, as a cross-sectional survey utilizing secondary data analysis, the causal relationship between variables could not be confirmed. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to explore causality. Secondly, some of the questionnaires used in the survey were not developed and validated through rigorous measurement development processes, such as those assessing workplace violence perpetration and victimization. Incorporating validated measures that capture various aspects of workplace violence experiences would enhance the reliability and validity of the study results. Thirdly, the number of children was not considered. For mothers with more than one child, psychological factors that could have been caused by taking care of multiple children, such as parenting stress, might affect the results. Future studies are required to take this into account to make a better understanding of parenting of mothers with ACEs.

5. Conclusions

The current study identified two distinct subgroups of ACEs based on ACE scores and predominant events, presenting differences in general and psychological characteristics as well as experiences of violence. These findings suggest ACEs may contribute to the amplification of psychological vulnerabilities and the occurrence of additional violent experiences even in adulthood. In other words, the low self-esteem induced from ACEs may lead to more self-destructive symptoms of psychological issues. Individuals with ACEs may also be trapped in a pattern of violence, manifesting as perpetration when they hold power and victimization when they lack power. This raises a call for the prevention of abuse and community violence considering the various types of ACEs. Furthermore, active prevention and intervention are required against experiencing violence by adults directly or indirectly in childhood. The findings offer valuable insights for preventing the negative effects of experiences of violence among mothers who are raising young children.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data utilized for this study are available by request through the website of KIHASA Health and Welfare Data Portal at http://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/kor/contents/ContentsList.html?rootId=2010001&menuId=2010117.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahn, J., Kang, S. K., Kim, H. L., Shin, H. R., Yoo, J., Lee, B. J., Lee, E., & Hwang, O. K. (2011). National survey of the child abuse 2011. Ministry of Health and Welfare.

- Anda, R. F., Brown, D. W., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2008). Adverse childhood experiences and prescription drug use in a cohort study of adult HMO patients. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-1

- Anda, R., Tietjen, G., Schulman, E., Felitti, V., & Croft, J. (2010). Adverse childhood experiences and frequent headaches in adults. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 50(9), 1473–1481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01756.x

- Ångerud, K., Annerbäck, E. M., Tydén, T., Boddeti, S., & Kristiansson, P. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptomatology among pregnant women. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 97(6), 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13327

- Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Hardcastle, K. A., Perkins, C., & Lowey, H. (2015). Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: A national survey. Journal of Public Health, 37(3), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdu065

- Chen, C., Sun, Y., Liu, B., Zhang, X., & Song, Y. (2022). The latent class analysis of adverse childhood experiences among Chinese children and early adolescents in rural areas and their association with depression and suicidal ideation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316031

- Christiaens, I., Hegadoren, K., & Olson, D. M. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with spontaneous preterm birth: A case–control study. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0353-0

- Clemens, V., Fegert, J. M., Kavemann, B., Meysen, T., Ziegenhain, U., Brähler, E., & Jud, A. (2023). Epidemiology of intimate partner violence perpetration and victimisation in a representative sample. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796023000069

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). John Wiley & Sons.

- Cooke, J. E., Racine, N., Plamondon, A., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2019). Maternal adverse childhood experiences, attachment style, and mental health: Pathways of transmission to child behavior problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 93, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.011

- Creasey, G., & Reese, M. (1996). Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of parenting hassles: Associations with psychological symptoms, nonparenting hassles, and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 17(3), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(96)90033-7

- Currie, J., & Spatz Widom, C. (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509355316

- Danese, A., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology & Behavior, 106(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

- Danese, A., & Tan, M. (2014). Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(5), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.54

- Dennis, C. H., Clohessy, D. S., Stone, A. L., Darnall, B. D., & Wilson, A. C. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences in mothers with chronic pain and intergenerational impact on children. The Journal of Pain, 20(10), 1209–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.04.004

- Deschênes, S. S., Graham, E., Kivimäki, M., & Schmitz, N. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of diabetes: Examining the roles of depressive symptoms and cardiometabolic dysregulations in the Whitehall II cohort study. Diabetes Care, 41(10), 2120–2126. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0932

- Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Williamson, D. F., Thompson, T. J., Clifton, M. L., & Giles, W. H. (2004). The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008

- Drevin, J., Stern, J., Annerbäck, E. M., Peterson, M., Butler, S., Tydén, T., Berglund, A., Larsson, M., & Kristiansson, P. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences influence development of pain during pregnancy. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 94(8), 840–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12674

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Goodman, L. A. (1974). The analysis of systems of qualitative variables when some of the variables are unobservable. Part I A modified latent structure approach. American Journal of Sociology, 79(5), 1179–1259. https://doi.org/10.1086/225676

- Greene, C. A., Haisley, L., Wallace, C., & Ford, J. D. (2020). Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clinical Psychology Review, 80, 101891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891

- Harris, J., III. (2001). Effects of child abuse on self esteem. In PCP 539 Counseling Issues in Life Span Development Assemblies of God Theological Seminary (pp. 1–14).

- Hockenberry, M. J., & Wilson, D. (2013). Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing. 9th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Jeon, M., & Kim, J. (2019). The role of self-efficacy and marital conflict in the relationship between parenting stress and depression among married women of infants. Korean Journal of Counseling, 20(1), 93–120.

- Jia, H., & Lubetkin, E. I. (2020). Impact of adverse childhood experiences on quality-adjusted life expectancy in the U.S. population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 102, 104418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104418

- Jonzon, E., & Lindblad, F. (2006). Risk factors and protective factors in relation to subjective health among adult female victims of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(2), 127–143.

- Kang, J. H. (2017). A study on the relationship of childhood abuse experience and life satisfaction. Korean Public Management Review, 31(2), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.24210/kapm.2017.31.2.013

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA). (2017). Family with children life experience. KIHASA Health and Welfare Data Portal. https://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/kor/board/BoardDetail.html

- LaBrenz, C. A., Panisch, L. S., Lawson, J., Borcyk, A. L., Gerlach, B., Tennant, P. S., Nulu, S., & Faulkner, M. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and outcomes among at-risk Spanish-speaking Latino families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(5), 1221–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01589-0

- Lanza, S. T., & Rhoades, B. L. (2013). Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science, 14(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1

- Lee, H., Kim, Y., & Terry, J. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on mental disorders in young adulthood: Latent classes and community violence exposure. Preventive Medicine, 134, 106039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106039

- Lee, K. A., Sacco, P., & Bright, C. L. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), excessive alcohol use and intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration among Black men: A latent class analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 121, 105273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105273

- Leeners, B., Richter-Appelt, H., Imthurn, B., & Rath, W. (2006). Influence of childhood sexual abuse on pregnancy, delivery, and the early postpartum period in adult women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.11.006

- Lubben, J., Blozik, E., Gillmann, G., Iliffe, S., von Renteln Kruse, W., Beck, J. C., & Stuck, A. E. (2006). Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben social network scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. The Gerontologist, 46(4), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.4.503

- McDonald, S. W., Madigan, S., Racine, N., Benzies, K., Tomfohr, L., & Tough, S. (2019). Maternal adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and child behaviour at age 3: The all our families community cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 118, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.013

- Metzler, M., Merrick, M. T., Klevens, J., Ports, K. A., & Ford, D. C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021

- Moe, V., Von Soest, T., Fredriksen, E., Olafsen, K. S., & Smith, L. (2018). The multiple determinants of maternal parenting stress 12 months after birth: The contribution of antenatal attachment style, adverse childhood experiences, and infant temperament. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01987

- Mosley-Johnson, E., Garacci, E., Wagner, N., Mendez, C., Williams, J. S., & Egede, L. E. (2019). Assessing the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and social well-being: United States longitudinal cohort 1995–2014. Quality of Life Research, 28(4), 907–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2054-6

- Nievar, M. A., Moske, A. K., Johnson, D. J., & Chen, Q. (2014). Parenting practices in preschool leading to later cognitive competence: A family stress model. Early Education and Development, 25(3), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.788426

- Park, J. H., & Chung, H. H. (2018). Mediating effects of social support and self-esteem on the relation between parenting stress and depression in women with infants and preschool children. Korean Journal of Educational Therapist, 10(1), 1–17.

- Parnes, M. F., & Schwartz, S. E. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences: Examining latent classes and associations with physical, psychological, and risk-related outcomes in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 127, 105562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105562

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package, 61(52), 18.

- Ryu, J. H., Lee, J., Jung, I., Song, A., & Lee, M. (2017). Understanding connections among abuse and violence in the life course (Report No. 2017–49). Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Sansone, R. A., Leung, J. S., & Wiederman, M. W. (2012). Five forms of childhood trauma: Relationships with employment in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(9), 676–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.007

- Shah, S. M., Al Dhaheri, F., Albanna, A., Al Jaberi, N., Al Eissaee, S., Alshehhi, N. A., Al Shamisi, S. A., Al Hamez, M. M., Abdelrazeq, S. Y., Grivna, M., & Betancourt, T. S. (2020). Self-esteem and other risk factors for depressive symptoms among adolescents in United Arab Emirates. PLoS One, 15(1), e0227483.

- Smith, B. T., Brumage, M. R., Zullig, K. J., Claydon, E. A., Smith, M. L., & Kristjansson, A. L. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among females in substance use treatment and their children: A pilot study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 24, 101571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101571

- Spann, S. J., Gillespie, C. F., Davis, J. S., Brown, A., Schwartz, A., Wingo, A., Habib, L., & Ressler, K. J. (2014). The association between childhood trauma and lipid levels in an adult low-income, minority population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 36(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.10.004

- Straus, M. A., & Hamby, S. L. (1997, March 24–28). Measuring physical & psychological maltreatment of children with the conflict tactics scales. In The Annual Meeting of Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL, United States. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED410301

- Su, S., Jimenez, M. P., Roberts, C. T., & Loucks, E. B. (2015). The role of adverse childhood experiences in cardiovascular disease risk: A review with emphasis on plausible mechanisms. Current Cardiology Reports, 17(10), 1–10.

- Thulin, E. J., Heinze, J. E., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2021). Adolescent adverse childhood experiences and risk of adult intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.030

- Topitzes, J., Pate, D. J., Berman, N. D., & Medina-Kirchner, C. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, health, and employment: A study of men seeking job services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 61, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.012

- Wang, X., Jiang, L., Barry, L., Zhang, X., Vasilenko, S. A., & Heath, R. D. (2024). A scoping review on adverse childhood experiences studies using latent class analysis: Strengths and challenges. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1695–1708. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231192922

- Wolford, S. N., Cooper, A. N., & McWey, L. M. (2019). Maternal depression, maltreatment history, and child outcomes: The role of harsh parenting. American journal of orthopsychiatry, 89(2), 181. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000365

- World Health Organization. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/adverse-childhood-experiences-international-questionnaire-(ace-iq)