ABSTRACT

Background: Despite numerous calls for a more evidence-based provision of post-disaster psychosocial support, systematic analyses of post-disaster service delivery are scarce.

Objective: The aim of this review was to evaluate the organization of post-disaster psychosocial support in different disaster settings and to identify determinants.

Methods: We conducted a meta-synthesis of scientific literature and evaluations of post-disaster psychosocial support after 12 Dutch disasters and major crises between 1992 and 2014. We applied systematic search and snowballing methods and included 80 evaluations, as well as grey and scientific documents.

Results: Many documents focus on the prevalence of mental health problems. Only a few documents primarily assess the organization of post-disaster psychosocial support and its determinants. The material illustrates how, over the course of two decades, the organizational context of post-disaster psychosocial support in the Netherlands has been influenced by changes in legislation, policy frameworks, evidence-based guidelines, and the instalment of formal expertise structures to support national and local governments and public services. Recurring organizational issues in response to events are linked to interrelated evaluation themes such as planning, training, registration, provision of information and social acknowledgement. For each evaluation theme, we identify factors helping or hindering the psychosocial support organization during the preparedness, acute and recovery phases.

Conclusions: The meta-synthesis illustrates that psychosocial service delivery has grown from a monodisciplinary to a multidisciplinary field over time. Suboptimal interprofessional collaboration poses a recurring threat to service quality. Despite the development of the knowledge base, post-disaster psychosocial support in the Netherlands lacks a systematic and critical appraisal of its functioning. Further professionalization is coupled with the strengthening of evaluation and learning routines.

HIGHLIGHTS

• Little academic and practical attention has been paid to the organization of post-disaster psychosocial support (PSS).

• Awareness of the need for post-disaster PSS, event type, collaboration and (social) media influence the organization of post-disaster PSS.

• Recurring evaluation themes are planning and training, registration, information and social acknowledgement.

• Suboptimal interprofessional collaboration poses a recurring threat to service quality.

Antecedentes: A pesar de las numerosas solicitudes de más prestaciones de apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre basadas en evidencia, los análisis sistemáticos de éstas son escasos.

Objetivo: Evaluar la organización del apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre en diferentes entornos de desastre e identificar los determinantes.

Métodos: Realizamos una meta-síntesis de la literatura científica y evaluaciones de apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre después de 12 desastres holandeses y crisis mayores entre 1992 y 2014. Aplicamos métodos de búsqueda sistemática y de ‘bola de nieve’ e incluimos 80 evaluaciones, así como documentos científicos y ‘grises’ (no publicados oficialmente).

Resultados: Muchos documentos se centran en la prevalencia de problemas de salud mental. Sólo unos pocos evalúan primariamente la organización del apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre y sus determinantes. El material ilustra cómo, en el transcurso de dos décadas, el contexto organizacional del apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre en los Países Bajos se encuentra influenciado por los cambios en la legislación, los marcos políticos, directrices basadas en la evidencia y la instalación de estructuras formales de expertos para apoyar a gobiernos locales y servicios públicos. Los problemas organizativos recurrentes en respuesta a los eventos están vinculados con aspectos de evaluación interrelacionados, tales como planificación, capacitación, registro, suministro de información y reconocimiento social. Para cada aspecto de evaluación, identificamos los factores que ayudan o dificultan la organización de apoyo psicosocial durante las fases de preparación, aguda y de recuperación.

Discusión: La meta-síntesis ilustra que la prestación de servicios psicosociales ha crecido a lo largo del tiempo de un campo mono-disciplinario a uno multidisciplinario. Las colaboraciones inter-profesionales que no son óptimas representan una amenaza recurrente para la calidad del servicio. A pesar de la base de conocimientos desarrollados, el apoyo psicosocial posterior al desastre en los Países Bajos carece de una evaluación sistemática y crítica de su funcionamiento. La profesionalización avanzada lleva aparejado el fortalecimiento de las rutinas de evaluación y aprendizaje.

背景:尽管已有多次呼吁更多循证的灾后心理社会支持,但关于灾后服务的系统分析仍然很少。

目标:评估不同灾害环境中灾后心理社会支持的组织情况,并识别其决定因素。

方法:我们对1992年-2014年间发生的12次荷兰灾难和重大危机之后的科学文献和灾后心理社会支持进行了综合分析。我们采用了系统搜索和滚雪球方法,最后纳入了80项评估以及灰色和科学文献。

结果:许多文献都关注精神健康问题的发生率。只有少数文件主要评估了灾后心理社会支持的组织及其决定因素。该材料说明了在20年的过程中,荷兰灾后社会心理支持的组织背景如何受到立法、政策框架、循证指南的变化以及支持国家和地方政府和公共服务的正式专业结构的影响。反复出现的组织问题与一些相互关联的评估主题有关,例如规划、培训、注册、信息提供和社会认可。对于每个评估主题,我们识别了准备、急性和恢复阶段可以帮助或阻碍心理社会支持组织的因素。

讨论:综合分析表明,随着时间的发展,提供心理社会服务已经从单一学科发展到多学科领域。次优的跨专业协作对服务质量构成了反复威胁。尽管知识库已有所发展,但荷兰的灾后心理社会支持缺乏对其运作的系统和批判性评估。进一步的专业化应与加强评估和学习规划相结合。

1. Introduction

Disasters can have enormous impacts on communities and individuals, often entailing negative consequences (Boin, ‘t Hart, Stern, & Sundelius, Citation2016; Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, Citation2010; Dyb et al., Citation2014; Norris et al., Citation2002; Yzermans et al., Citation2005). The delivery of effective and organized post-disaster psychosocial support (PSS) can aid affected communities and individuals in dealing with the negative consequences of disasters (Bisson et al., Citation2010; Pfefferbaum & North, Citation2016; Reifels et al., Citation2013; Suzuki, Fukasawa, Nakajima, Narisawa, & Kim, Citation2012; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013; Vymetal et al., Citation2011). However, the delivery of services during and after disasters is often met with conditions of collective stress and uncertainty (Boin & Bynander, Citation2015; Comfort, Citation2007; Reifels et al., Citation2013; Rosenthal, Charles & ‘t Hart, Citation1989; Scholtens, Citation2008). Hence, in addition to research on effective post-disaster PSS interventions for the health and well-being of affected persons (Dieltjens, Moonens, van Praet, de Buck, & Vandekerckhove, Citation2014; Gouweloos, Dückers, Te Brake, Kleber, & Drogendijk, Citation2014), some authors have recommended further study of the organizational dimension of post-disaster PSS (Bisson et al., Citation2010; Dückers, Yzermans, Jong, & Boin, Citation2017; Reifels et al., Citation2013; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013).

Various problems have been addressed and solutions proposed to increase the professionalization of post-disaster PSS. Several studies contributed to the development of expert and evidence-informed guidelines and to systems of planning and delivery of post-disaster PSS (Bisson et al., Citation2010; Dückers, Witteveen, Bisson, & Olff, Citation2017; Suzuki et al., Citation2012; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013; Witteveen et al., Citation2012). In general, a gap exists between norms as prescribed in post-disaster PSS guidelines and actual service delivery (Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013). Studies show variations between geographical regions and post-disaster PSS programmes (Dückers et al., Citation2018; Witteveen et al., Citation2012). Planning and coordination are considered to be critical elements in disaster preparedness and management (Boin & ‘t Hart, Citation2003; Boin & Bynander, Citation2015) and are increasingly emphasized in post-disaster PSS. Collaboration and cooperation between professionals and organizations remain challenging as many different organizations and professionals are involved. As the delivery of psychosocial services in a post-disaster setting remains difficult (Goldman & Galea, Citation2014), increased knowledge of the effective organization of post-disaster PSS and factors that help or hinder that organization is required.

1.1. Objective

The objective of this study is to evaluate the organization of post-disaster PSS in different disaster settings and to identify factors that help or hinder this. A meta-synthesis of the available documents on Dutch disasters is conducted. This methodology is appropriate because the growing body of academic writings and grey literature on post-disaster PSS has not been examined systematically with the objective of drawing organizational lessons.

This research seeks to contribute to the knowledge base on post-disaster PSS by applying a less traditional research focus. So far, the post-disaster PSS literature has been dominated primarily by psychological, clinical and epidemiological research. In general, little attention has been paid to the organization of service delivery in a post-disaster setting. This study adds to the literature by identifying factors that help or hinder the organization of post-disaster PSS. We analyse the post-disaster PSS organization from a multidisciplinary perspective, including public administration, organization studies and psychology. The outline of this paper is as follows. First, we will describe the methodology, including our selection of disaster cases, the systematic search strategy and the inclusion criteria. Then, we will present the results of our analysis, followed by a discussion of the findings and a general conclusion.

2. Methodology

We conducted a meta-synthesis (Mays, Pope, & Popay, Citation2005), which is a qualitative systematic review method, to compare, integrate and aggregate the findings of scientific research and evaluations of the organization of post-disaster PSS in the Netherlands. A qualitative synthesis is a process of extracting and interpreting data into a collective form (Campbell et al., Citation2012), giving room for new insights and a better understanding of the research topic, especially in cases of multiple events (Walsh & Downe, Citation2005). The meta-synthesis method can be used ‘to explore barriers and facilitators to the delivery and uptake of services’ (Grant & Booth, Citation2009, p. 26). Although most qualitative review methods only include scientific research based on primary qualitative data (e.g. interviews or observations) (Britten et al., Citation2002), our meta-synthesis includes evaluations of the organization of post-disaster PSS as well. Research in health and policy disciplines increasingly argues for the inclusion of high-quality evidence based on non-scientific research, such as high-quality evaluation reports, to support decision making by policy makers and managers (Kuipers, Wirz, & Hartley, Citation2008; Mays et al., Citation2005). It is therefore important to notice that a meta-synthesis is essentially different from other types of qualitative reviews, for example, critical literature reviews (Thorne, Jensen, Kearney, Noblit, & Sandelowski, Citation2004). In our meta-synthesis, we include scientific literature based on primary data, as well as grey and formal evaluation reports.

Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) suggest a seven-step approach for conducting a meta-ethnography. These steps are also applicable to a meta-synthesis (Britten et al., Citation2002). We highlight the important steps of narrowing the scope of the research (step 1), defining inclusion (step 2), analysis (steps 3–6) and writing down (step 7). Step 1 of the methodology involves defining the area of interest, the goal of the research and the research question. Hence, the remainder of this paragraph will address the inclusion of disasters and documents and the selection criteria applied. Moreover, a comprehensive search strategy was used to identify relevant articles and grey literature on the selected disasters, utilizing systematic search methods and snowballing methodology (Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were predefined, and documents were assessed by multiple reviewers. The review team included social scientists with a background in psychology, epidemiology and public administration, some of whom had previous experience in conducting systematic reviews. Finally, included articles were coded and partially double-checked by a second researcher. Based on the coding, several evaluation themes emerged and were reorganized into a scheme.

2.1. Selection of Dutch disasters

To identify relevant Dutch disasters, five selection criteria were used. First, a time frame between 1990 and 2014 was adopted in which events could be identified. Based on expert opinions, we decided that this time span reflects a relevant period for investigating the organization of post-disaster PSS, as the relevant history of PSS in the Netherlands is considered to have begun in 1990.Footnote1 Secondly, the event must have inflicted harm to such an extent that it would lead to Dutch casualties, either on Dutch or on foreign soil. Thirdly, the event must have endangered communities’ social and physical safety. Fourthly, the event must have endangered vital interests, such as economic values. Fifthly, the event should have led to the involvement of public administration in more than the emergency response. No databases exist that include all disasters; hence, expert opinions were used to come up with a non-exclusive list of Dutch disasters. In total, 12 disasters were included, comprising technological, transportation, human-made and natural disasters ().

Table 1. List of included Dutch disasters.

2.2. Search strategy and selection criteria

A multidimensional search was conducted to find both grey and scientific documents (). The search included the following steps. First, a systematic search was conducted in several scientific databases. The Cochrane, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and PILOTS databases between 1990 and 2014 were searched. Keywords for the search included terms associated with the specific disasters, such as ‘q fever’ or ‘flood’; terms associated with psychosocial service delivery, such as ‘psycho-social’; terms associated with the nature of the work, such as ‘rescue’ and ‘emergency’; and terms associated with document types, such as ‘assessment’ or ‘evaluation’. Secondly, personal archives of two Dutch disaster experts involved in the aftermaths of several of the events included were searched to find documents related to the 12 Dutch disasters. All documents eligible for full reading from the systematic search and documents from the personal collections were snowballed to further complete the list of documents associated with the disasters. Inclusion criteria for documents were: (1) their connection to one of the 12 Dutch disasters; (2) addressing post-disaster PSS for Dutch citizens; (3) reference to the organization of post-disaster PSS; and (4) being a form of informal or formal evaluation. Articles and documents were read by two independent readers. Disagreements in the reviewing process were resolved through discussion. An expert was consulted when there was disagreement.

2.3. Analysis

For the document analysis, a distinction in disaster phases was used, i.e. preparedness, acute and recovery (which is a simplification of other models that use a similar division but consider, for instance, prevention, mitigation and evaluation as distinct phases, e.g. Alexander, Citation2003; Lettieri, Masella, & Radaelli, Citation2009; Quarantelli, Citation1988). Coding was centred on central themes, reflecting the five main service categories as distinguished within the Dutch post-disaster PSS guidelines (Impact, Citation2014), within these phases:

Basic relief: this refers to emergency and rescue work in the direct aftermath of a disaster and to the emergency support that is offered directly afterwards, such as safety, medical assistance, food and water, medication and shelter.

Information provision is considered to be an essential element in post-disaster PSS service delivery (Ammerlaan, Citation2009; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013), and can refer both to aspects of psycho-education and to aspects of the event itself, the people affected (including next of kin) and expected developments in the aftermath.

Emotional and social support: a supportive context and social acknowledgement should be offered (Bonanno et al., Citation2010; Hobfoll et al., Citation2007; Kaniasty & Norris, Citation2004; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013). Indications exist that lack of social support leads to a higher prevalence of trauma-related mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e.g. Bonanno et al., Citation2010; Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, Citation2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, Citation2003).

Practical support is aimed at assisting those affected with, for example, administrative tasks, household tasks, legal advice and financial support. Disasters often cause affected individuals to be confronted with tasks they normally could easily fulfil, or with tasks that had been unknown to them. Legal advice, for example, belongs to the latter category (Dückers & Thormar, Citation2015; Impact, Citation2014).

Medical assistance and health care, such as prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment, should be provided, especially when affected groups have an increased risk of health complaints (Bisson et al., Citation2010; Te Brake & Dückers, Citation2013).

All included articles were coded by at least one researcher using MAXQDA, a software package for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis. Forty-three per cent of the data was coded by two researchers. The coding framework followed the five themes mentioned above against the background of the quality model in the Dutch post-disaster PSS guidelines and can be found in Appendix 1 (Impact, Citation2014). Based on the framework, key concepts that emerged from the coding were noted. The PSS-related findings from the evaluations per event were structured chronologically in an overview that illustrates which problems were identified, together with lessons and recommendations for the provision of PSS formulated by the evaluators (see Appendix 3). In the next section, the findings per coding theme and disaster phase are described. The findings are structured according to a set of overarching ‘evaluation themes’, reflecting omnipresent issues in PSS delivery since the early 1990s. Besides a description of issues according to each evaluation theme, we looked for specific factors evaluators recognized as determinants helping or hindering the organization of post-disaster PSS.

3. Results

The systematic search of scientific databases yielded 259 records. After screening of titles and abstracts, 92 records were retained and fully read. Three records addressed the organization of post-disaster PSS in the Netherlands. The search of experts’ personal collections resulted in 94 records. Snowballing of scientific literature and grey documents resulted in 275 records. After exclusions, the expert collections and snowballing yielded 77 results. Finally, a total of 80 records was included for analysis. See for a detailed overview of the inclusion process.

3.1. Description of included documents

The included documents were divided into four categories. Formal evaluation reports are reports that have formal mandates to evaluate or investigate a disaster, given by governments or government institutions, for example. ‘Grey documents’ refer to documents that address some form of evaluation of psychosocial care after disasters but that do not have a formal mandate. Scientific research refers to documents that follow scientific methods, yet are not published in peer-reviewed journals. Examples are doctoral dissertations or research reports. The last category is scientific publications in a peer-reviewed journal (). Three peer-reviewed scientific publications were found to address the organization or evaluation of post-disaster PSS. Document analysis shows that evaluation of post-disaster PSS is often included as a small part of general crisis response evaluations. Stand-alone evaluations of post-disaster PSS services are amply done.

Table 2. List of included Dutch disasters and documents.

3.2. Synthesis

A total of 80 documents was coded using the heuristic framework in Appendix 1. See Appendix 2 for the coding tree and Appendix 3 for a detailed overview of the analysed documents, including details on author, methods and main findings. Only three peer-reviewed scientific publications focused on the organization of post-disaster PSS (Boin, van Duin, & Heyse, Citation2001; Jong, Dückers, & van der Velden, Citation2016) or drew a conclusion on the organization of post-disaster PSS (Carlier & Gersons, Citation1997). The changes in the breadth of post-disaster PSS that we identified in the collected material, as well as the recurring evaluation themes considered by different authors across events, and the general factors helping or hindering the organization of post-disaster PSS will be considered in the following subsections.

3.2.1. Changes in the breadth of post-disaster PSS over time

The document analysis points to changes due to problems and deficiencies in the provision of services for people affected by the Bijlmermeer disaster in 1992 – across most of the coding themes – that resulted in recommendations and lessons that were implemented in the PSS approach in later disasters and major events. In addition, the scope of post-disaster PSS evaluations broadened from a rather medical, mainly psychological orientation on professional health care to an explicit assessment of social and emotional support, practical support and the provision of information. The observations and conclusions by evaluators are indicative of the broadening of post-disaster PSS over time, which is reflected in two ways in the documents.

First, since 1992, there has been a growing awareness of the long-term psychosocial consequences of disasters and crises (Witteveen, Citation2006) and the need for post-disaster PSS in the form of coordinated care provision (Carlier, van Uchelen, & Gersons, Citation1995; van Hemert & Smeets, Citation2004). This has resulted in a wider range of suitable interventions, such as a ‘one-stop shop’ (Carlier et al., Citation1995; Meijer, Oudkerk, van den Doel, Augusteijn-Esser, & Oedayraj Singh Varma, Citation1999), digital information and referral centres (Impact, Citation2012; Te Brake & Schaap, Citation2017) and specialized on-site reception (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid, 2009). Secondly, there is a clear shift of emphasis from complaints and clinical interventions based on psychology and psychiatry (Carlier & Gersons, Citation1997; Carlier, Gersons, & Uchelen, Citation1993; Verschuur et al., Citation2004b) to general post-disaster health research. Moreover, authors apply a broader perspective on well-being and support, with an increased focus on needs and problems and particular risk groups (de Jong & van Schaik, Citation1994; Drogendijk, van der Velden, Kleber, & Gersons, Citation2004; Jong et al., Citation2016; Impact, Citation2004b; van der Bijl, van der Velden, Govers, & van Dorst, Citation2012; van Duin, Tops, Wijkhuijs, Adang, & Kop, Citation2012). The coding scheme (Appendix 1) (Impact, Citation2014) that we used covers this broadened range in PSS themes. No additional themes were identified during the analysis.

3.2.2. Recurring organizational evaluation themes

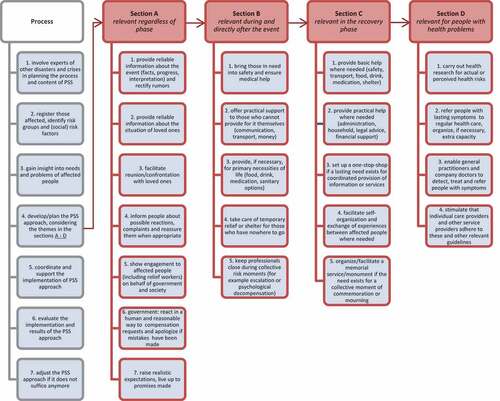

In light of developments in the organization of post-disaster PSS, it is possible to identify a series of omnipresent overarching evaluation themes in the reflections and conclusions by different authors, all related to (shortcomings in) the organization of post-disaster PSS. gives an overview of the evaluation themes and their causal relationships as implied in the documents. Conceptually, the themes could be linked to three phases. In the preparedness phase, the documents elaborate on post-disaster PSS problems that have to do with ‘planning’ and ‘training’. Besides ‘planning’ of recovery in the acute phase, another issue that remains problematic over the study period is the ‘registration’ of affected individuals and other post-disaster PSS target groups. Finally, two evaluation themes play roles in the recovery phase. Authors repeatedly describe problems concerning ‘information’ and ‘social acknowledgement’.

Figure 2. Psychosocial support (PSS) evaluation themes and explanatory factors identified. The PSS delivery problems described in the included works centre on five distinct evaluation themes. In the preparedness phase, shortcomings are linked to training and planning. A recurring issue in the acute phase is the registration of affected individuals, which is linked to the immediate planning of services. In the recovery phase, evaluators repeatedly describe problems connected to information and social acknowledgement. The one-way arrows represent causal relations across stages, implied in the material studied. The two-way arrows represent associations where the direction is difficult to ascertain. The line of reasoning reflected in the documents points at sequential interdependencies across the crisis life cycle. Deficiencies in training and planning in the preparedness phase influence registration and planning in the acute phase. Registration and planning in the acute phase influence information and social acknowledgement. All PSS evaluation themes are influenced by four generic explanatory factors: awareness, event type, collaboration and (social) media.

visualizes several associations and causal relations across phases assumed by different authors in the material studied (shown as dotted arrows; double arrows where the direction can go two ways). The evaluation themes are influenced by four generic factors: event type, awareness, collaboration and (social) media, which we will discuss in Section 3.2.3. In the remainder of this section, we will describe why these themes are seen as important and why they are recurring.

3.2.2.1. Planning

Planning aims at identifying and developing processes to effectively respond to disasters before the event takes place. Examples of such processes are the registration of affected individuals, quick response or post-disaster PSS at the event scene or in shelter locations. Over time, planning has gained an important role in pre-disaster preparation and has grown from being nearly absent (Carlier et al., Citation1993; Kroon & Overdijk, Citation1993) to being universal in preparation and even a legal responsibility (Alders, Belonje, van Den Berg, Ten Duis, & Doelen, Citation2001). The importance of planning is recognized by several authors (not only before but also for the recovery phase and the acute phase) (Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, Citation2009a) because plans can assist in structuring behaviour during and after disasters (Kroon & Overdijk, Citation1993), promote making sense of a situation, and address responsibilities and tasks of individual stakeholders (Alders et al., Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg, Citation2001a).

Although planning has an added value, several recurring issues are associated with planning. First, plans need to stay up to date (Alders et al., Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid, Citation2009; Jeeninga, de Vos, Wijkmans, & Bon-Martens, Citation2010), incorporating the changing local, organizational and governmental contexts and societal demands. Secondly, plans can never fully integrate the flexible nature of disasters. For example, it is difficult to take into consideration the scale of the disaster (Torenvlied et al., Citation2015; van Deursen, Prins, Kelderman, & Priester, Citation1993) and the length of the aftermath (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Impact, Citation2004a). As a result, plans must primarily be aimed at ‘guiding’ organizations and professionals through the uniqueness of each new disaster (van Duin et al., Citation2012).

Thirdly, authors note that plans should be embedded within organizations and the networks in which they function, and that more attention for implementation is preferred (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; van der Meijden, Roorda, IJzermans, van der Velden, & Grievink, Citation2006). Fourthly, the use of plans requires that the parties implementing them constantly practise their plans and update their knowledge of those plans; yet, this aspect is often overlooked (Alders et al., Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid, Citation2011; Oosting et al., Citation2001).

3.2.2.2. Training

Training is the second recurring theme in the preparation phase. Evaluations or discussions on almost every disaster emphasize the need for adequate, even structural, training of professionals in assessing and delivering PSS. Even the most recent evaluations still focus on improved training for adequate response in PSS (Laurier, Ten Brink, de Gouw, & Corvers-Debers, Citation2013; Te Brake & Schaap, Citation2017). Authors state that training can help to secure plans within organizations (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; Kroon & Overdijk, Citation1993), that it makes people familiar with their tasks (Alders et al., Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009) and that it is helpful in creating a thorough understanding of the field (Laurier et al., Citation2013).

Difficulties lie in the connectedness of the quality of training with the presence and quality of plans (Alders et al., Citation2001; Oosting et al., Citation2001). Moreover, training design influences effectiveness. The need for realistic training based on existing plans is emphasized (Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, Citation2009b). Some authors recommend incorporating a culturally sensitive approach in training to create awareness of cultural differences (Drogendijk et al., Citation2004; Netten, Citation2005).

3.2.2.3. Registration

Registration of victims and affected persons emerged as an important theme and seems to serve several goals. First, registration serves as an indicator of the scale of the disaster for first-response organizations and to facilitate identification of victims and their next of kin (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009b, Citation2011). Insufficient information about the fate of loved ones can lead to feelings of uncertainty and disquiet (Alders et al., Citation2001; de Boer & van der Heide, Citation2010; Noordegraaf et al., Citation1993). When affected persons are not registered at all, this generates dissatisfaction (Soeteman, Citation2009), especially when errors in registration occur (Alders et al., Citation2001) or when, during registration, a distinction is made that does not do justice to the actual course of events (Laurier et al., Citation2013).

Secondly, registration provides important information for the organization of the recovery phase (Laurier et al., Citation2013). Authors state that registration is important to guarantee continuity of care (Kroon & Overdijk, Citation1993) and to enable an adequate flow of information and practical assistance to those in need (Nuijen, Citation2006; Oosting et al., Citation2001). Existing registration (e.g. primary care databases) can be used to monitor (health) problems over time and consequently to direct care (Dorn, ten Veen, & IJzermans, Citation2007; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002).

Registration of victims and affected persons has remained a constant challenge over the years (Alders et al., Citation2001; Groen, Koekkoek, & Slump, Citation2001; Informatieen Adviescentrum, Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; Oosting et al., Citation2001; Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, Citation2009b). For example, registration to monitor affected persons requires specific knowledge (Yzermans, Dirkzwager, Kerssen, Cohen-Bendahan, & Ten Veen, Citation2006), and a uniform registration format does not exist (Informatie en Adviescentrum, Citation2001, Citation2003b). It is difficult to organize training to prepare for registration and to do justice to the complexity of registration during the acute phase (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, 2009b), yet it is necessary to clarify roles and responsibilities (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2011).

3.2.2.4. Information

Information delivery during the recovery phase deals with sending information about the nature and range of the disaster, the settlement of claims, legal procedures, commemoration ceremonies, etc. Quick and adequate information is seen as a minimal requirement for post-disaster PSS (e.g. Alders et al., Citation2001; Meijer et al., Citation1999; Oosting et al., Citation2001). It helps to reduce uncertainty among affected persons (Meijer et al., Citation1999) and helps them to get a grip on the situation again (Oosting et al., Citation2001). The lack of adequate information can have far-reaching consequences, significantly complicating the recovery in terms of length of time and content of the recovery (Boin et al., Citation2001; Witteveen, Citation2006; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002).

Focal points in evaluations are transparency in information processes and debunking of rumours (Meijer et al., Citation1999; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012), the creation of a (digital) one-stop shop (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Carlier et al., Citation1995; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002; Impact, Citation2004a; Meijer et al., Citation1999), the alignment of different information flows (Carlier, Citation1996) and the creation of accessible and understandable information, especially in dealing with technical information (Bosman et al., Citation2004) or with different cultural groups (Groen et al., Citation2001; Netten, Citation2005). A timely delivery of information is important, yet many disasters are characterized by a late and cautious response by authorities in addressing the event (van Dijk et al., Citation2010; Gersons, Carlier, & IJzermans, Citation2000; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002; Klerx van Mierlo, Citation2009; van der Bijl, van der Velden, Govers, & van Dorst, Citation2012; van Duin et al., Citation2012b; Verschuur et al., Citation2004b). Solutions can be found in early impact assessments on health communication (Grievink, van der Velden, de Vries, Mulder & Smilde - van den Doel, Citation2006), frequent communication (Oosting et al., Citation2001) and early meetings with affected persons (de Boer & van der Heide, Citation2010).

3.2.2.5. Social acknowledgement

Many documents point to the importance of social acknowledgement, simultaneously addressing the multifaceted nature of social acknowledgement as a concept (Jong et al., Citation2016; Laurier et al., Citation2013; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012). On the one hand, social acknowledgement is seen as a goal in itself, something that should actively be delivered through, for example, house visits by mayors (Jong et al., Citation2016; Laurier et al., Citation2013) or (health-care) professionals (Gouweloos & Den Brinke, Citation2013; van der Velden & Kleber, Citation2000).

On the other hand, social acknowledgement is seen as a by-product of post-disaster activities, such as information delivery (Laurier et al., Citation2013; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012), the organization of a one-stop shop serving the needs of those affected (Impact, Citation2012, te Brake & Schaap, Citation2017), a particular case management approach (Laurier et al., Citation2013) and the simplification of bureaucratic structures resulting in, for example, easier access to (semi-)governmental institutions and health-care organizations (Alwart, Macnack, Pengel-Forst, & Sarucco, Citation1993; Laurier et al., Citation2013; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002). Several documents address the effect of correct registration of affected persons on their perceived experience of social acknowledgement (Laurier et al., Citation2013; Oosting et al., Citation2001).

3.2.3. Recurring explanatory factors

The analysis of the included documents points to several generic and recurring explanatory factors in the organization of post-disaster PSS. We will describe them below.

3.2.3.1. Awareness

Political and governmental actors need to be aware of the need for post-disaster PSS. This awareness has increased over time (Coebergh, Citation1999; Crisis Onderzoeksteam, Citation1999; Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg, Citation2001b; van Deursen et al., Citation1993), resulting in, for example, planning templates (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009). However, many challenges remain. For example, investments in preparation for long-term recovery after disasters are amply done (Alders et al., Citation2001), and the embedment of post-disaster PSS structures in local governments remains problematic (Crisis Onderzoeksteam, Citation1999).

Costs of training can be high (Te Brake & Schaap, Citation2017), while at the same time professionals have little time to participate (Oosting et al., Citation2001). As a result, the organization of training for post-disaster PSS is highly dependent on the political priority that is given to post-disaster PSS preparation (Alders et al., Citation2001; Laurier et al., Citation2013). A lack of political priority (Klerx van Mierlo, Citation2009; Meijer, Oudkerk, van Den Doel, Augusteijn-Esser & Oedayraj Singh Varma, Citation1999; van Duin, Overdijk, & Wijkhuijs, Citation1998a) or insufficient knowledge of psychosocial needs (Laurier et al., Citation2013; Nuijen, Citation2006; Oosting et al., Citation2001) can result in a lack of awareness for giving or organizing social acknowledgement.

3.2.3.2. Disaster type

The different events analysed in this research can be categorized differently. There are sudden-onset disasters with either a short or a lingering aftermath and slow-onset disasters; in this study, mostly infectious diseases. Slow-onset events are difficult to detect, and involved parties have difficulties setting priorities for the recovery (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Crisis Oonderzoeksteam, Citation1999; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012). Slow-onset disasters lack a position in planning and training (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Impact, Citation2004a). It is difficult to oversee the scale of the disaster (van Deursen et al., Citation1993) and the length of the aftermath (Bosman et al., Citation2004; Impact, Citation2004b). Registration of affected persons is a constant factor that requires attention (Bosman et al., Citation2004).

3.2.3.3. Collaboration

Many documents emphasize the importance of collaboration for the organization of post-disaster PSS. Collaboration is problematic across several of the recurring evaluation themes. For example, dissemination of plans and templates among different partners was sometimes lacking (Alders et al., Citation2001; Oosting et al., Citation2001), there was a lack of agreement about the contents of the plans (Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg, Citation2001b), and information exchange between different partners remains problematic (Kroon & Overdijk, Citation1993; van Duin et al., Citation1998b).

Several causes of collaboration issues are mentioned. First, problems are rooted in a lack of knowledge of the existing and required network (Alders et al., Citation2001; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009; Laurier et al., Citation2013; Oosting et al., Citation2001) and associated roles and responsibilities (Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2009). Secondly, international boundaries cause the international exchange of information to remain problematic even today (Torenvlied et al., Citation2016; van Duin, Overdijk, & Wijkhuijs, Citation1998b). Thirdly, interests may be difficult to align – for example, economic interests versus health interests (van der Bijl et al., Citation2012) – between different organizations and stakeholders, such as governmental departments, semi-governmental organizations and hospitals (Crisis Onderzoeksteam, Citation1999; Jeeninga et al., Citation2010; Oosting et al., Citation2001; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012; van Duin et al., Citation2012). Fourthly, a monodisciplinary focus on the organization of the crisis response and its associated recovery phase may result in, for example, an inadequate and delayed dissemination of information (Impact, Citation2004a; Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV), Citation2011). A monodisciplinary focus also prevents organizations from adequately learning from each other (Nuijen, Citation2006).

3.2.3.4. (Social) media

The role of the media – and later on social media – is mentioned as an important factor in the organization of post-disaster PSS. Repeatedly, media are found to give confusing and ambiguous information about disasters (KLM Arbo Services, Citation2004; van Duin et al., Citation1998a; Witteveen, Citation2006). Recently, social media has become influential in information delivery and retrieval (van Duin et al., Citation2012; Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, Citation2009b), enabling a quick spread of information and rumours and causing organizations to experience less control over information flows. Social media watching can be considered a crucial part of crisis response and communication (Veiligheidsregio Kennemerland, 2009b).

4. Discussion

In this research, we systematically investigated the organization of post-disaster PSS in the Netherlands over time and identified several determinants. To increase our understanding of the organization of post-disaster PSS, we followed an interpretative approach, using a meta-synthesis to aggregate information on 12 different Dutch disasters. To our knowledge, this is the first synthesis in the field of post-disaster PSS to use this approach and include such a large number of disasters. Our review included scientific documents and evaluation reports. In this section, we will reflect on our findings, make suggestions for further research and discuss the limitations of this research.

4.1. Changes in organizational context of post-disaster PSS over time

The body of knowledge captured in the documents that we analysed points to a growing and developing field of post-disaster PSS in which policies and interventions are embedded within national, regional and local governments, as well as semi-governmental and private partners. This is reflected in several main topics. First, the plea for coordinated provision of care after the Bijlmer aeroplane crash (Carlier et al., Citation1995; Meijer, Citation1992; van Hemert & Smeets, Citation2004) has been realized over the years (Informatie en Adviescentrum, Citation2003a; Citation2003b; Laurier et al., Citation2013; Oosting et al., Citation2001; Te Brake & Schaap Citation2017), reflected in, for example, the forms of working agreements and partnerships. Secondly, in the Netherlands – particularly in reaction to the negative post-disaster PSS evaluation after the Bijlmer aeroplane disaster in 1992 and the generally more positive evaluation of the Enschede fireworks disaster in 2000 – a national PSS knowledge centre was established by three ministries in 2002, and a health research and monitoring expert committee was installed in 2004 to support local and national governments during crises with a public health dimension (Behbod et al., Citation2017).

Since the early 2000s, post-disaster PSS has been incorporated as a public health and public safety responsibility in legislation and strategy documents (e.g. Bruinooge et al., Citation2012; Dückers, Citation2012; Wet Publieke gezondheid, Citation2012; Wet Veiligheidsregio, Citation2010). National evidence-based post-disaster PSS guidelines for the general population and uniformed services were developed for governments and service providers (e.g. Impact, Citation2010, Impact, Citation2014; also see te Brake et al., Citation2009). In addition, since the Enschede fireworks disaster, coordinated service structures for affected populations have become standard post-disaster PSS instruments (Behbod et al., Citation2017; Dückers, Witteveen, et al., Citation2017; Te Brake & Schaap, Citation2017; Vereniging voor Nederlandse Gemeenten, Citation2004; Yzermans & Gersons, Citation2002).

These developments and structures are reflected in the documents that we analysed. They gradually affected the planning and evaluation of the later events over the course of our time frame, influencing the background against which the authors described and reviewed post-disaster PSS delivery in the context of the 12 events. The changes in organizational context follow from the broader exchange and cooperation between governments, professional service providers and academics, and resulted in quality improvement instruments at the local, regional and national levels in the Netherlands. As such, we can conclude that many of the lessons and recommendations listed in Appendix 3 were actually implemented. Nevertheless, the fact that the quality management system of post-disaster PSS has been enriched does not take away the need for continued investment in preparation for PSS by responsible governments and agencies, nationally and locally (de Bas, Helsloot, & Dückers, Citation2017).

4.2. Further research

The changes and innovations highlighted so far give rise to new challenges in addition to the old ones that still need to be maintained. First, our findings show that although post-disaster PSS in the selected time frame was amply evaluated, a systematic approach was lacking. This seriously reduces the possibility of learning from major events, limits possibilities for quality improvement and makes estimates on (cost-)effectiveness and other quality criteria in relation to the health of affected individuals and groups problematic.

The inclusion of only three relevant peer-reviewed scientific articles analysing organizational aspects of PSS leads us to believe that there is still little academic and practical attention being paid to this topic in the Netherlands. The majority of the scientific publications on post-disaster PSS is aimed at understanding health effects resulting from disasters, while little attention is given to the organization of post-disaster PSS during each phase of the disaster. This can be seen as surprising, given the implications of suboptimal post-disaster PSS for affected persons, and also given the risks involving suboptimal PSS for public leaders in terms of accountability (Dückers, Yzermans, et al., Citation2017). Developing coherent evaluation models for post-disaster PSS focusing on unravelling contexts, mechanisms and outcomes is a promising next step in improving the organization of post-disaster PSS.

Secondly, as a result of the broadening of the scope of post-disaster PSS, the multidisciplinary nature of post-disaster PSS requires researchers to adopt new theoretical perspectives, such as interorganizational and network theory, to better understand the organizational dynamics of post-disaster PSS. In terms of training and planning, this requires organizations and professionals to develop new skills and integrate knowledge about psychosocial principles and new ways of working into their crisis management activities and normal routines (Dückers, Yzermans, et al., Citation2017). Interprofessional collaboration could be enhanced by training PSS actors to become more familiar with their and each other’s roles (Boin & Bynander, Citation2015; D’Amour, Ferrada-Videla, Rodriguez & Beaulieu, 2005) and with viewing the organization of planning more as a process than as a product (Perry & Lindell, Citation2003). Training may also enhance managers’ knowledge of contextual and organizational factors and their improvisational skills (Perry & Lindell, Citation2003).

Thirdly, the evaluation themes in this article seem to have sequential interdependence. Shortcomings in the preparedness phase affect other themes in successive phases. For example, information retrieved from registration of affected persons is essential for the layout of the recovery phase, yet registration – despite national initiatives to formulate solutions – remains difficult to organize and the suboptimal transfer of information is likely to hinder the provision of PSS to people with needs and problems in future events.

Our findings corroborate earlier findings on the interconnectedness of these phases (e.g. Kapucu & van Wart, Citation2006; Neal, Citation1997; Quarantelli, Citation1988, Quarantelli, Citation2005). Moreover, this research shows that post-disaster PSS has a distinct role during every phase of the disaster management cycle and not only during the recovery phase. Based on the collected material, we conclude that the success or failure of PSS in the recovery phase is highly dependent on activities in the preparedness and acute phases. Hence, the organization of post-disaster PSS deserves an important and visible place during every step of disaster and emergency management.

We can conclude that coordinated collaboration across the borders of disciplines and professions remains at the heart of the organization of post-disaster PSS. This is in line with earlier research on post-disaster PSS (e.g. Bisson et al., Citation2010; Dückers et al., Citation2018; Reifels et al., Citation2013; Witteveen et al., Citation2012) and findings in the general crisis management literature (Alexander, Citation2003; Boin & Bynander, Citation2015; Neal, Citation1997; Quarantelli, Citation1988). General issues associated with coordination are a lack of an exclusive definition of coordination (Boin & Bynander, Citation2015), preparedness that is insufficient for dealing with the flexible nature of disasters (Ansell, Boin, & Keller, Citation2010), and interagency and intergovernmental alignment (‘t Hart, Rosenthal, & Kouzmin, Citation1993). Similar problems are found in this research: implementation of expert-informed or evidence-based knowledge into practice is difficult, and alignment of interprofessional, interorganizational and intergovernmental interests remains problematic, especially during creeping crises like the examples mentioned and infectious diseases or zoonosis, owing to conflicting interests of involved ministries and the ministry of health (e.g. Haalboom, Citation2017; van der Bijl et al., Citation2012).

Initiatives to address the issues found in our study locally and nationally will potentially be affected by the decentralization and decoupling of semi-governmental institutions, an international trend in Western European countries (e.g. Bannink & Ossewaarde, Citation2012; Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011). Coordinative processes for interprofessional and interorganizational practice require continuous attention. We described how coordination roles were legally allocated to regional public health and public safety actors who need to align and connect their respective networks on behalf of PSS. Moreover, post-disaster PSS opened up a broad spectrum of organizations and professionals, expanding the diversity of the domain rapidly. To optimize coordination, Boin and Bynander (Citation2015) suggest a combination of top–down and bottom–up coordination consisting of professional reliance (competent and skilled professionals in a working context with a management that supports timely and adequate action in different time stages). However, it is the role of the professional that remains largely underexposed in the literature (including the meta-synthesis described in this article). Improvement of interprofessional collaboration requires knowledge of how collaboration is and can be organized in uncertain and pressured settings and which professional skills are required.

Finally, the focus of the meta-synthesis has been entirely on the Netherlands since the beginning of the 1990s. It would be very valuable to compare the findings to the development of post-disaster PSS in other countries and to compare the issues encountered, lessons formulated, solutions tested and factors that helped or hindered the provision of services to people affected by disasters and major incidents. In earlier studies, notable differences were described in six European regions in their adherence to evidence-based guidelines (Witteveen et al., Citation2012) and the developmental statuses of the local PSS planning and delivery systems; these developmental statuses were confirmed to be associated with country characteristics such as good governance, access to general practitioners and hospitals, and public and private health expenditure (Dückers, Witteveen, et al., Citation2017). Since the adherence to guidelines and the organization of PSS are not similar across regions, reflecting differences in tradition, culture and other conditions, it is not likely that our results are universally applicable to, for instance, the southern, south-east and eastern regions of Europe, given the differences in professional health-care capacity and lower developmental scores of PSS planning and delivery systems. We expect that the organization of services in countries in northern, western and central Europe, with similar guidelines, professional standards, institutions and cultural values, will experience similar challenges.

4.3. Limitations

In this study, a substantial number of publications was assessed on the organization of PSS during different events. However, several limitations should be discussed. First, this meta-synthesis included academic literature, systematic evaluation and grey literature. We should note that the evaluations reflect the prevailing ideas of that time and other interests. For example, topics for evaluation differ per time and per disaster as a result of political attention to specific subjects. In other words, the objectivity of the evaluations should be considered with caution. Secondly, the quality of the evaluations depends on the methodology used. Only a few evaluations explicitly mentioned methodological considerations, and overall, no systematic evaluation approach was used. Nevertheless, in our opinion, the included documents contain indispensable information.

Thirdly, although we have included a large number of documents using systematic search methods, some proportion of evaluations and grey documents might not show up in databases or through snowballing. We feel confident that with our systematic search through scientific databases, snowballing and the use of expert input, we have included the most important documents. Fourthly, a meta-synthesis aims at aggregating information on specific phenomena, but as the basis of this method is interpretative research, and the research itself is also interpretative, generalizability of the findings should be considered with caution. We recommend replication of our study in other countries. In this light and more broadly, we recommend international cooperation and investment in the development of comprehensive PSS evaluation frameworks and instruments. The availability of high-quality evaluations is a crucial precondition for an informative meta-analysis.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we systematically examined available evaluations of the organization of post-disaster PSS in the Netherlands over time and identified several continual evaluation themes and explanatory factors. Based on our collected data, we can draw several important conclusions. Despite the implications of suboptimal post-disaster PSS, there is still little academic and practical attention being paid to the organization of post-disaster PSS. Post-disaster PSS has become professionalized over the years, yet we identified recurring challenges in the multidisciplinary landscape where post-disaster PSS is shaped and implemented. These challenges have to do with a lack of awareness and coordination and collaboration between network partners. We have shown the interconnectedness of different disaster phases and activities within those phases. Several important factors hindering or helping the organization of post-disaster PSS were found. The coordination of interprofessional and interorganizational processes requires continuous attention. Further professionalization is coupled with the strengthening of evaluation and learning routines.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jonna Lind for her assistance with the literature search, and Berthold Gersons and Joris Yzermans for giving the researchers access to their personal archives with evaluations, articles, books, reports and correspondence on many of the disasters and crises analysed in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See the interviews with Berthold Gersons and René Stumpel by Dückers (Citation2013; Citation2015); also, an overview of ‘the psychosocial dimension of disasters’ by Giel (1989) is entirely comprised of international examples and research findings and contains no empirical Dutch material.

References

- *Alders, J. G. M., Belonje, M. M., van den Berg, A., ten Duis, H. J., & Doelen, A. (2001). Cafébrand Nieuwjaarsnacht – Publieksversie. Rotterdam: Phoenix & den Oudsten. Retrieved from http://nationaalbrandweerdocumentatiecentrum.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Publieksversie.pdf

- Alexander, D. (2003). Towards the development of standards in emergency management training and education. Disaster Prevention and Management: an International Journal, 12(2), 113–39.

- *Alwart, I., Macnack, U., Pengel-Forst, C., & Sarucco, M. (1993). Rouw en rituelen na de vliegtuigramp. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 48, 1056–1066.

- Ammerlaan, K. (2009). Na de ramp: De rol van de overheid bij de (schade) afwikkeling van rampen vanuit een belangenperspectief van de slachtoffers (Doctoral dissertation). Universiteit van Tilburg, Tilburg. Retrieved from https://pure.uvt.nl/portal/en/publications/na-de-ramp(6f95b5b6-b3f7-4088-a29b-033ae651e058).html

- Ansell, C., Boin, A., & Keller, A. (2010). Managing transboundary crises: Identifying the building blocks of an effective response system. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 18(4), 195–207.

- Arbo Service, KLM. (1999). Protocol 1. Amsterdam: Author.

- Bannink, D., & Ossewaarde, R. (2012). Decentralization: New modes of governance and administrative responsibility. Administration & Society, 44(5), 595–624.

- Behbod, B., Leonardi, G., Motreff, Y., Beck, C. R., Yzermans, J., Lebret, E., … Close, R. (2017). An international comparison of the instigation and design of health registers in the epidemiological response to major environmental health incidents. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 23(1), 20–28.

- Bisson, J. I., Tavakoly, B., Witteveen, A. B., Ajdukovic, D., Jehel, L., Johansen, V. J., & Olff, M. (2010). TENTS guidelines: Development of post-disaster psychosocial care guidelines through a Delphi process. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(1), 69–74.

- Boin, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 63(5), 544–553.

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2016). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/comparative-politics/politics-crisis-management-public-leadership-under-pressure-2nd-edition?format=PB&isbn=9781107544253

- Boin, A., & Bynander, F. (2015). Explaining success and failure in crisis coordination. Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 97(1), 123–135.

- *Boin, A., van Duin, M., & Heyse, L. (2001). Toxic fear: The management of uncertainty in the wake of the Amsterdam air crash. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 88(2–3), 213–234.

- Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & La Greca, A. M. L. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1–49.

- *Bosman, A., Mulder, Y. M., de Leeuw, J. R. J., Meijer, A., Du Ry van Beest Holle, M., Kamst, R. A., & Ruijten, M. W. M. M. (2004). Vogelpest Epidemie 2003: Gevolgen voor de volksgezondheid. Onderzoek naar risicofactoren, gezondheid, welbevinden, zorgbehoefte en preventieve maatregelen ten aanzien van pluimveehouders en personen betrokken bij de bestrijding van AI H7N7 epidemie in Nederland. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. Retrieved from https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/630940001.pdf

- Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766.

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215.

- *Broekman, H. (2000). Na de vuurwerkramp: Peiling werkdruk en ondersteuningsbehoefte Huisartsen Enschede. Enschede: Coördinatie Commissie Vuurwerkramp.

- Bruinooge, P., Bitter, R., Helsloot, I., Dekker, K., Stierhout, J., & Langelaar, J. (2012). Bevolkingszorg op orde 2.0: Eigentijdse bevolkingszorg, volgens afspraak. Den Haag: Veiligheidsberaad.

- Campbell, R., Pound, P., Morgan, M., Daker-White, G., Britten, N., Pill, R., … Donovan, J. (2012). Evaluating meta ethnography: Systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 15(43). doi:10.3310/hta15430

- *Carlier, I. V. E., Gersons, B. P. R., & Uchelen, J. J. (1993). De Bijlmermeer-vliegramp. Een onderzoek naar de psychische gevolgen bij getroffenen en hun commentaar op de geboden nazorg. Amsterdam: Academisch Medisch Centrum Amsterdam.

- *Carlier, I. V. E., van Uchelen, J. J., & Gersons, B. P. R. (1995). De bijlmermeer-vliegramp. Een vervolgonderzoek naar de lange termijn psychische gevolgen en de nazorg bij getroffenen. Amsterdam: Academisch Medisch Centrum Amsterdam.

- *Carlier, I. V. E. (1996). Studiedag hulp bij rampen en calamiteiten; je kan er beter op voorbereid zijn! Aanbevelingen naar aanleiding van de Bijlmerramp. Amsterdam: Academisch Medisch Centrum Amsterdam.

- *Carlier, I. V. E., & Gersons, B. P. R. (1997). Stress reactions in disaster victims following the Bijlmermeer plane crash. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 10(2), 329–335.

- *Coebergh, J. W. W. (1999). Zorg voor de volksgezondheid na de vliegtuigramp in de Bijlmermeer; de beladen nasleep. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Geneeskunde, 143(46), 2301–2305.

- *Carlier, I. V. E., Sijbrandij, E. M., Meijer, J. E. M., & Gersons, B. P. R. (2001). De late hulpverlening voor posttraumatische stressklachten bij getroffenen van de Bijlmermeer vliegramp. Amsterdam: AMC.

- Comfort, L. K. (2007). Crisis management in hindsight: Cognition, communication, coordination, and control. Public Administration Review, 67(1), 189–197.

- *Crisis Onderzoeksteam. (1999). De uitbraak van de veteranenziekte te Bovenkarspel: Een evaluatie van de epidemiebestrijding. Leiden: Author.

- D’Amour, D., Ferrada-Videla, M., San Martin Rodriguez, L., & Beaulieu, M. D. (2005). The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(1), 116–131.

- de Bas, M., Helsloot, I., & Dückers, M. L. A. (2017). De preparatie op de nafase binnen veiligheidsregio’s: Een verkennend onderzoek. Tijdschrift voor Veiligheid, 17, 3–16. Retrieved from http://postprint.nivel.nl/PPpp6607.pdf

- *de Jong, J. T. V. M., & van Schaik, M. M. (1994). Culturele en religieuze aspecten van rouw- en traumaverwerking naar aanleiding van de Bijlmerramp. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 4,293–303.

- *de Vries, M., & Rooze, M. W. (2008). Gezondheidsonderzoek na rampen in Nederland. Diemen: Impact.

- *de Boer, W., & van der Heide, A. (2010). Landelijke aanpak nazorg vliegramp Tripoli. Magazine Nationale Veiligheid en Crisisbeheersing, 8(3), 26–30. Retrieved from https://www.ifv.nl/kennisplein/wet-veiligheidsregios-wvr/nieuws/magazine-nationale-veiligheid-en-crisisbeheersing-mei-juni-2010-artikel-rampen-kennen-geen-grenzen

- Dieltjens, T., Moonens, I., van Praet, K., de Buck, E., & Vandekerckhove, P. (2014). A systematic literature search on psychological first aid: Lack of evidence to develop guidelines. PloS one, 9(12), e114714.

- *Drogendijk, A. N., van der Velden, P. G., Kleber, R. J., & *Gersons, B. P. R. (2004). Leidende en misleidende verwachtingen. Een kwalitatief onderzoek onder Turkse getroffenen van de vuurwerkramp Enschede omtrent de psychosociale nazorg. Zaltbommel: Instituut voor Psychotrauma (IVP).

- *Drogendijk, A. N., van der Velden, P. G., Boeije, H. R., Gersons, B. P. R., & Kleber, R. J. (2005). De ramp heeft ons leven verwoest. De psychosociale weerslag van de vuurwerkramp Enschede op Turkse getroffenen. Medische Antropologie, 17(2), 217–232.

- *Dorn, T., ten Veen, P. M. H., & IJzermans, C. J. (2007). Gevolgen van de nieuwjaarsbrand in Volendam voor de gezondheid. Eindrapport van de monitoring in huisartsenpraktijken en apotheken. Utrecht: NIVEL. Retrieved from https://www.nivel.nl/sites/all/modules/custom/wwwopac/adlib/publicationDetails.php?database=ChoicePublicat&priref=1001477&width=650&height=500&iframe=true

- *Drogendijk, A. N. (2012). Long term psychosocial consequences for disaster affected persons belonging to ethnic minorities (Doctoral dissertation). Stichting Arq, Diemen.

- Dückers, M. (2012). Richting geven aan de laatste schakel: De nafase. Rijksbrede versterking van herstel en nazorg bij rampen en crises. Den Haag: Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie.

- Dückers, M. (2013). Lessen uit twintig jaar rampenhulpverlening: Berthold Gersons over zijn ervaringen bij de grootste rampen in Nederland. Cogiscope, 10(3), 20–25.

- Dückers, M. (2015). In de werkkamer. In gesprek met René Stumpel, arts en directeur publieke gezondheid bij de GGD GHOR. Cogiscope, 12(4), 44–47.

- Dückers, M. L. A., & Thormar, S. B. (2015). Post-disaster psychosocial support and quality improvement: A conceptual framework for understanding and improving the quality of psychosocial support programs. Nursing & Health Sciences, 17(2), 159–165.

- Dückers, M. L. A., Thormar, S. B., Juen, B., Ajdukovic, D., Newlove, L., & Olff, M. (2018). Measuring and modelling the quality of 40 post-disaster psychosocial support programmes. PLOS ONE, 13(2), e0193285.

- Dückers, M. L. A., Witteveen, A. B., Bisson, J. I., & Olff, M. (2017). The association between disaster vulnerability and post-disaster psychosocial service delivery across Europe. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(4), 470–479.

- Dückers, M. L. A., Yzermans, C. J., Jong, W., & Boin, A. (2017). Psychosocial crisis management: the unexplored intersection of crisis leadership and psychosocial support. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 8(2), 94–112.

- Dyb, G., Jensen, T. K., Nygaard, E., Ekeberg, Ø., Diseth, T. H., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Thoresen, S. (2014). Post-traumatic stress reactions in survivors of the 2011 massacre on Utøya Island, Norway. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 361–367.

- *Gersons, B. P. R., & Carlier, I. V. E. (1993a). Plane crash crisis intervention: A preliminary report from the Bijlmermeer, Amsterdam. Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 14, 109–116.

- *Gersons, B. P. R., & Carlier, I. V. E. (1993b). De Bijlmer-ramp: Crisisinterventie en consultatie. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 10, 1043–1055.

- *Gersons, B. P. R., Carlier, I. V. E., & IJzermans, C. J. J. M. (2000). “In de Spiegel der emoties”. Onvoorziene langetermijngevolgen van de Bijlmervliegramp. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid, 55, 876–889.

- *Gersons, B. P. R., Huijsman-Rubingh, R. R. R., & Olff, M. (2004). De psychosociale zorg na de vuurwerkramp in Enschede; lessen van de Bijlmer-vliegramp. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 148(29), 1426–1430.

- *Giebels, E. (2016). Communicatie met en nazorg aan nabestaanden. Magazine Nationale Veiligheid en Crisisbeheersing, 2, 10–11.

- Giel, R. (1989). De psychosociale kant van rampen. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 3, 223–239.

- Goldman, E., & Galea, S. (2014). Mental health consequences of disaster. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 169–183.

- *Gouweloos, J., & den Brinke, T. (2013). Bevindingen getroffenen Poldercrash. Resultaten van drie belrondes onder getroffenen van het vliegtuigongeluk met de TK 1951 op 25 februari 2009. Diemen: Stichting Impact. Retrieved from https://www.ifv.nl/kennisplein/ghor-algemeen/publicaties/bevindingen-getroffenen-poldercrash-resultaten-van-drie-bellrondes

- Gouweloos, J., Dückers, M., Te Brake, H., Kleber, R., & Drogendijk, A. (2014). Psychosocial care to affected citizens and communities in case of CBRN incidents: A systematic review. Environment International, 72, 46–65.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108.

- Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. British Medical Journal, 331(7524), 1064–1065.

- *Groen, H., Koekkoek, M., & Slump, G. J. (2001). Sociale wederopbouw na de vuurwerkramp. Eerste peiling voortgang maatregelen. Amsterdam: DSP. Retrieved from https://publicaties.dsp-groep.nl/getFile.cfm?file=01_02_Sociale%20wederopbouw%20na%20de%20vuurwerkramp%20Eerste%20peiling%20voortgang%20maatregelen_02-20012.pdf&dir=rapport

- *Gutteling, J., & Torenvlied, R. (2016). Informatievoorziening naar de Tweede Kamer, media en samenleving. Magazine Nationale Veiligheid en Crisisbeheersing, 2, 12–13.

- Grievink, L., van der Velden, P. G., de Vries, M., Mulder, Y.M., & den Doel, Smilde-van, D.A. (2006). Gezondheidsonderzoek na rampen: een inventarisatie van wensen en verwachtingen. Bilthoven: RIVM.

- Haalboom, A. F. (2017). Was de uitbraak van Q-koorts een verassing? Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 161(33), D1786.

- ‘t Hart, P., Rosenthal, U., & Kouzmin, A. (1993). Crisis decision making: The centralization thesis revisited. Administration & Society, 25(1), 12–45.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Watson, P., Bell, C. C., Bryant, R. A., Brymer, M. J., Friedman, M. J., … Ursano, R. J. (2007). Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: Empirical evidence. Psychiatry, 70, 283–315.

- *Informatieen Adviescentrum. (2001). Jaarverslag 2000. Enschede: Informatie en adviescentrum.

- *Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (IGZ). (2001a). Onderzoek vuurwerkramp Enschede Rapportage geneeskundige hulpverlening getroffenen vuurwerkramp Enschede. Utrecht: IGZ.

- *Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (IGZ). (2001b). Rapport evaluatie geneeskundige hulpverlening cafébrand nieuwsjaarsnacht 2001. Utrecht: IGZ. Retrieved from http://www.algemeneehbodenbosch.nl/bibliotheek_info/cafebrand_vollendam_hulpverlening.pdf

- *Informatieen Adviescentrum. (2002). Jaarverslag 2001. Enschede: Informatie en adviescentrum.

- *Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (IGZ). (2003). Waakzaamheid blijft geboden. Een oriënterend onderzoek naar de hulpverlening bij psychische problemen na de cafébrand in Volendam. Den Haag: IGZ. Retrieved from http://www.nazorgvolendam.nl/pdf/Waakzaamheid%20blijft%20geboden.pdf

- *Informatieen Adviescentrum. (2003a). Jaarverslag 2002. Enschede: Informatie en adviescentrum.

- *Informatieen Adviescentrum. (2003b). Eindrapportage. Enschede: Informatie en adviescentrum.

- *Informatieen Adviescentrum. (2003c). Eindevaluatie. Enschede: Informatie en adviescentrum.

- *Impact. (2004a). Monitor organisatie psychosociale zorg n.a.v. Aviaire Influenze onder pluimvee. Eindrapportage. Amsterdam: Author.

- *Impact. (2004b). Samenvattingen rapporten en monitor Aviaire Influenza. Amsterdam: Author.

- Impact. (2010). Richtlijn psychosociale ondersteuning geüniformeerden. Diemen: Author.

- *Impact. (2012). Eindrapportage IVC Vliegramp Tripoli. Diemen: Author.

- Impact. (2014). Multidisciplinary guideline for post-disaster psychosocial support. Diemen: Author.

- *Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV). (2009). Poldercrash 25 februari 2009. Een onderzoek door de Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid, in samenwerking met de Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg. Den Haag: IOOV. Retrieved from https://www.inspectie-jenv.nl/Publicaties/rapporten/2009/06/22/poldercrash-25-februari-2009

- *Jeeninga, W., de Vos, E. H. M., Wijkmans, C. J., & Bon-Martens, M. J. H. (2010). Q-koortsbestrijding door de GGD; evalueren en leren. Infectieziekten Bulletin, 21(9), 342–345. Retrieved from https://www.rivm.nl/Documenten_en_publicaties/Algemeen_Actueel/Uitgaven/Infectieziekten_Bulletin/Archief_jaargangen/Jaargang_21_2010/Nummers_jaargang_21/November_2010/Inhoud_November_2010/Q_koortsbestrijding_door_de_GGD_evalueren_en_leren/Download/Q_koortsbestrijding_door_de_GGD_evalueren_en_leren

- *Inspectie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (IOOV). (2011). Schietincident in ‘De Ridderhof’ Alphen aan den Rijn. Den Haag: IOOV. Retrieved from https://www.inspectie-jenv.nl/Publicaties/rapporten/2011/11/25/rapportage-schietincident-in-%E2%80%98de-ridderhof%E2%80%99-alphen-aan-den-rijn

- *Joustra, T. H. J., Muller, E. R., & van Asselt, M. B. A. (2015). MH17. Passagiersinformatie. Den Haag: Onderzoeksraad voor de Veiligheid.

- *Jong, W., Dückers, M. L. A., & van der Velden, P. (2016). Crisis leadership by mayors: A qualitative content analysis of newspapers and social media on the MH17 disaster. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 24(4), 286–295.

- Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (2004). Social support in the aftermath of disasters, catastrophes, and acts of terrorism: Altruistic, overwhelmed, uncertain, antagonistic, and patriotic communities. In R. J. Ursano, A. E. Norwoord, & C. S. Fullerton (Eds.), Bioterrorism: Psychological and public health interventions (pp. 200–229). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kapucu, N., & van Wart, M. (2006). The evolving role of the public sector in managing catastrophic disasters: Lessons learned. Administration & Society, 38(3), 279–308.

- *Kroon, M. B., & Overdijk, W. I. (1993). Psychosocial care and shelter following the Bijlmermeer air disaster. Crisis, 14, 117–125.

- *KLM Arbo Services. (2004). Medisch Onderzoek Vliegramp Bijlmermeer. Schiphol: Author.

- *Klerx van Mierlo, F. (2009). Faro gevolgen enquête 3. Tilburg: Intervict. Retrieved from https://www.vliegrampfaro.nl/publicaties/faro-gevolgen-enquetes/

- Kuipers, P., Wirz, S., & Hartley, S. (2008). Systematic synthesis of community-based rehabilitation (CBR) project evaluation reports for evidence-based policy: A proof-of-concept study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 8(1), 3.

- *Laurier, J. P., Ten Brink, C. E., de Gouw, J. M. M., & Corvers-Debers, E. M. R. (2013). Over napijn en nazorg. Eindverslag van de onafhankelijke adviescommissie nazorg schietincident Alphen aan den Rijn. Alphen aan den Rijn: Onderzoekscommissie Nazorg schietincident. Retrieved from https://www.ifv.nl/kennisplein/nazorg-en-nafase/publicaties/over-napijn-en-nazorg-eindverslag-van-de-onafhankelijke-adviescommissie-nazorg-schietincident-alphen-aan-den-rijn

- Lettieri, E., Masella, C., & Radaelli, G. (2009). Disaster management: Findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prevention and Management: an International Journal, 18(2), 117–136.

- Mays, N., Pope, C., & Popay, J. (2005). Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10, 6–20.

- *Meijer, J. S. (1992). Een vliegtuigramp in een huisartspraktijk; posttraumatische reacties in de eerste vier weken na de ramp in de Bijlmermeer. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Geneeskunde, 136(52), 2553–2558.

- *Meijer, T. A. M., Oudkerk, R. H., van Den Doel, M., Augusteijn-Esser, M. J., & Oedayraj Singh Varma, T. (1999). Een beladen vlucht. Eindrapport Bijlmer Enquête. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

- Neal, D. M. (1997). Reconsidering the phases of disasters. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 15(2), 239–264.

- *Netten, J. C. M. (2005). Cultuur sensitieve psychosociale zorg na rampen. Lessons learned and good practices. Psychosociale zorg aan getroffenen uit etnische groepen bij de Bijlmer vliegramp en Enschede vuurwerkramp. Diemen: Impact.

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- *Noordegraaf, G. J., Savelkoul, T. J. F., Van der Werken, C., Kon, M., Vandenbroucke, C. M. J. E., & Meulenbelt, J. (1993). De opvang en behandeling van 14 slachtoffers van het vliegtuigongeval in Faro, Portugal, in het calamiteitenhospitaal Utrecht van 23 tot en met 29 december 1992. De Bilt: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu.

- Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 65(3), 207–239.

- *Oosting, M., Beckers-de Bruijn, M. B. C., Enthoven, M. E. E., de Ruiter, J., Savelkoul, T. J. F., & Tümer, Y. I. (2001). De vuurwerkramp. Eindrapport. Rotterdam: Phoenix & den Oudsten. Retrieved from https://dloket.enschede.nl/loket/sites/default/files/DOC/Eindrapport%20Commissie%20Oosting%20compleet.pdf

- *Nuijen, M. (2006). Nieuwjaarsbrand Volendam 2001. Lessen voor later. Volendam: CRN Het Anker. Retrieved from http://www.nazorgvolendam.nl/pdf/Cat0106boek%20Volendaminternet.pdf

- Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L., & Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52–73.

- Perry, R. W., & Lindell, M. K. (2003). Preparedness for emergency response: Guidelines for the emergency planning process. Disasters, 27(4), 336–350.

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2016). Child disaster mental health services: A review of the system of care, assessment approaches, and evidence base for intervention. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(1), 5.