ABSTRACT

Background

The effect of dissociation and parenting style on the relationship between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms has not previously been investigated.

Objective

The aim of this study was to develop a moderated mediation model to assess whether the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms is mediated by dissociation and moderated by parental maltreatment.

Methods

Inpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar depression (BP) were recruited. Self-reported and clinical rating scales were used to measure the level of dissociation, psychotic symptoms, history of psychological trauma and parental maltreatment. The PROCESS macro in SPSS was used to estimate path coefficients and adequacy of the moderated mediation model. High betrayal trauma (HBT), low betrayal trauma (LBT), paternal maltreatment, and maternal maltreatment were alternatively entered into the conceptual model to test the adequacy.

Results

A total of 91 patients (59 with MDD and 32 with BP) were recruited, with a mean age of 40.59 ± 7.5 years. After testing with different variables, the moderated mediation model showed that the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms was mediated by dissociation and moderated by maternal maltreatment. A higher level of maternal maltreatment enhanced the effect of LBT on dissociation.

Conclusions

Healthcare workers should be aware of the risk of developing psychotic symptoms among depressive patients with a history of LBT and maternal maltreatment.

HIGHLIGHTS

We explored associations between trauma, dissociation, and psychotic symptoms.

Low betrayal trauma (LBT) fit the conceptual model.

Dissociation mediated the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms.

Maternal maltreatment exacerbated the effect of LBT on dissociation.

Antecedentes: El efecto de disociación y el estilo parental en la relación entre el trauma psicológico y los síntomas psicóticos no se han investigado previamente.

Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue desarrollar un modelo de mediación moderada para evaluar si la asociación entre trauma psicológico y síntomas psicóticos es mediada por la disociación y moderada por el maltrato de los padres.

Métodos: Fueron reclutados pacientes hospitalizados con trastorno depresivo mayor (TDM) y depresión bipolar (DB). Se utilizaron escalas clínicas y de auto-reporte para medir el nivel de disociación, síntomas psicóticos, antecedentes de trauma psicológico y maltrato de los padres. La macro PROCESS en SPSS se utilizó para estimar los coeficientes de ruta y adecuación del modelo de mediación moderada. Alto exposición al trauma de traición (HET), baja exposición al trauma de traición (BET), maltrato paterno y maltrato materno fueron alternativamente ingresados en el modelo conceptual para probar la adecuación.

Resultados: Se reclutaron un total de 91 pacientes (59 con TDM y 32 con DB), con una edad media de 40,59 ± 7,5 años. Después de probar con diferentes variables, el modelo moderado de mediación mostró que la asociación entre BET y síntomas psicóticos estuvo mediada por la disociación y moderada por el maltrato materno. Un nivel superior del maltrato materno aumentó el efecto de BET sobre la disociación.

Conclusiones: Los trabajadores del área de la salud deben ser conscientes del riesgo del desarrollo de síntomas psicóticos entre los pacientes depresivos con antecedentes de BET y maltrato materno.

背景:解离和养育方式对心理创伤和精神病症状之间关系的影响以前没有被研究过。

目的:本研究旨在开发一个调节中介模型, 以评估心理创伤和精神病症状之间的关联是否由解离中介并由父母虐待调节。

方法:招募患有重度抑郁障碍 (MDD) 和双相抑郁 (BP) 的住院患者。使用自我报告和临床评估量表来衡量解离程度, 精神病症状, 心理创伤史和父母虐待。 使用SPSS 中的 PROCESS 宏估计路径系数和适度中介模型的充分性。将高背叛创伤 (HBT), 低背叛创伤 (LBT), 父亲虐待和母亲虐待交替输入概念模型以检验其充分性。

结果:共招募了 91 名患者 (59 名 MDD 和 32 名 BP), 平均年龄为 40.59 ± 7.5 岁。在对不同变量进行检验后, 有调节的中介模型表明 LBT 与精神病症状之间的关联是由解离介导的, 并由母体虐待调节。较高水平的母体虐待增强了 LBT 对解离的影响。

结论:医护人员应该意识到有 LBT 和母亲虐待史的抑郁患者出现精神病症状的风险。

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychotic symptoms in depressive disorder

The impact of psychotic symptoms in patients with depressive disorder has been investigated. Depression with psychotic features has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality, however it may be underdiagnosed and undertreated (Rothschild, Citation2013). The presence of psychotic symptoms among patients with depressive disorder may worsen disease progression. Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have been reported to have more severe depressive episodes with psychotic episodes than without psychotic episodes (Forty et al., Citation2009). In addition, mood congruent psychotic features in MDD have been positively associated with obsessive-compulsive traits and severity of depression (Tonna, De Panfilis, & Marchesi, Citation2012). Psychotic symptoms in patients with depression would result in an increased burden of treatment, such as the use of combination therapy (antidepressants plus antipsychotics) or electroconvulsive therapy (Rothschild, Citation2013; Wijkstra et al., Citation2015). Investigating psychotic symptoms in depression may help to clarify the aetiology and lead to the development of treatment strategies.

1.2. Psychological trauma and dissociation in developing psychotic symptoms

The association between psychotic symptoms and psychological trauma has gained increasing research attention. A previous study recruiting patients with depressive disorder demonstrated that those with psychotic symptoms were significantly more likely to report a history of severe psychological trauma than those without psychotic symptoms (Holshausen, Bowie, & Harkness, Citation2016). Other studies have also demonstrated that patients with a history of psychosis had a high incidence of psychological trauma (Bebbington et al., Citation2004), physical and sexual abuse (Read & Argyle, Citation1999). Freeman and Fowler reported that childhood trauma may be associated with the development of negative schematic beliefs, leading to misinterpretation of normal stimuli and paranoia (Freeman & Fowler, Citation2009). Another comprehensive review indicated the association between psychological trauma and psychotic-like symptoms, which may be involved in the temporal lobe dysfunction(Schiavone, McKinnon, & Lanius, Citation2018). However, the causality between trauma and psychotic symptoms remains controversial (Morgan & Fisher, Citation2007; Read, van Os, Morrison, & Ross, Citation2005). Hence, further path analysis or explorations of possible mediators can be helpful to clarify the mechanisms of interactions.

To explore the mechanisms of the interaction between trauma and psychotic symptoms, it is necessary to assess other factors associated with psychotic symptoms, such as dissociation. A large epidemiological study in the general population demonstrated that dissociation is related to many kinds of mental disorders, particularly psychotic experiences (Cernis, Evans, Ehlers, & Freeman, Citation2021). In patients with psychotic disorder, an experience-sampling study revealed that a state of dissociation could significantly predict the later occurrence of auditory hallucinations (Varese, Udachina, Myin‐Germeys, Oorschot, & Bentall, Citation2011). Accordingly, further studies are warranted to explore the role of dissociation in the relationship between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms.

1.3. The role of parenting style

Family-related factors may be associated with the formation of psychosis. A meta-analysis demonstrated that parental communication deviance, defined as vague, fragmented, and contradictory communication in the family, was a risk factor for the development of psychosis in genetically sensitive offspring (de Sousa, Varese, Sellwood, & Bentall, Citation2014). Therefore, parenting style may also play an important role in the development of psychosis. Previous studies have reported an association between parental rearing styles and the occurrence of psychotic disorder (Parker, Fairley, Greenwood, Jurd, & Silove, Citation1982; Willinger, Heiden, Meszaros, Formann, & Aschauer, Citation2002). Furthermore, positive symptoms (delusions or hallucinations) have been associated with a higher level of parental maltreatment, including rejection and overprotection/control (Catalan et al., Citation2017; McCreadie, Williamson, Athawes, Connolly, & Tilak-Singh, Citation1994).

Parenting style has also been associated with psychological trauma. A previous study indicated that individuals with psychological trauma were less likely to have had ideal parenting during childhood (Catalan et al., Citation2017). Another study of patients with eating disorder reported that childhood trauma was more prevalent in patients exposed to the parenting style of affectionless control (Monteleone et al., Citation2020). Moreover, paternal warmth has been reported to attenuate the association between childhood trauma and alcohol-related problems (Shin et al., Citation2019). Due to the potential link between parenting style and psychological trauma or psychotic symptoms, investigations on the effect of parenting style on the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms are needed.

1.4. Aim of the current study

Although the potential effects of psychological trauma, dissociation and parenting style on psychotic symptoms have been identified in previous studies, no studies have explored the interactions between them. In addition, although the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms is well known, the roles of dissociation and parenting style in this association have yet to be explored. Furthermore, the effects of different types of psychological trauma on psychotic symptoms remain unclear. Given this gap in the knowledge, the aim of this study was to develop a moderated mediation model to estimate the effect of parenting style and dissociation on the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms among patients with depressive disorder. Clinically non-psychotic patients were selected because the retrospective reporting of psychological trauma and parenting style may be confounded by reality distortion in patients with full-blown psychotic disorder. The hypothesis of the current study was that dissociation mediates the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms, and that parenting style moderates the association between psychological trauma and dissociation.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

Data from the current study were derived from the ‘Investigations on interpersonal adversity, psychiatric status, and socio-cognitive function (IAPS)’ project. The IAPS project recruited inpatients with MDD, bipolar disorder with depressive episodes (BP), and schizophrenia. This project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital (KSPH-2014-34 and KSPH-2017-04) and followed the protocols of the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed written informed consent before entering the study.

2.2. Participants and procedures

The recruitment periods of the IAPS project were from 30 December, 2014 to 21 December 2016, and from 17 May, 2017 to 21 December, 2020 at Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital, Taiwan. Data of the patients with MDD and BP were used in this study. The inclusion criteria were: 1) new admission due to MDD or BP according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria; 2) age between 20 and 50 years; and 3) a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese. Patients were not recruited for the study if they: 1) exhibited any level of intellectual disability; 2) had organic syndromes; 3) could not follow the directions of the researchers to complete the study due to disturbances caused by their mental illness, such as a manic episode; and 4) had difficulty in expressing language.

The recruited inpatients with MDD and BP were assessed during the first week of admission. Both self-report measures and clinical interviews were conducted to collect information on demographics, dissociation, traumatic experiences, maternal maltreatment, depression and psychotic symptoms.

2.3. Outcome measures

2.3.1. Clinical interview scores

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), and Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS)

The PANSS was designed to measure the severity of psychotic symptoms, negative symptoms and general psychopathology (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, Citation1987). The PANSS is a clinical interview scale composed of 30 questions, with each question being scored using a Likert scale from one to seven. The Chinese-Mandarin version of the PANSS has been shown to have acceptable reliability and validity (Wu, Lan, Hu, Lee, & Liou, Citation2015). To develop the conceptual model, only positive symptoms of the PANSS (PANSS-P) with seven items were used in this study, indicating the presence of psychotic symptoms (e.g. hallucinations or delusions). A higher total PANSS-P score indicates more severe psychosis.

The HAMD was used to assess depression in this study (Williams, Citation1988). The HAMD is a clinical interview scale containing 17 items, with a total score from 0 to 52. A higher total HAMD score indicates more severe depression. In this study, the HAMD was used to compare the severity of depression, but it was not entered into the analysis of the conceptual model.

The CADSS was used to measure the state of dissociation in this study. The CADSS is a 27-item scale with 19 subject-rated items and 8 items scored by an observer. It is scored using a Likert scale from 0 to 4, and it has been shown to have good interrater reliability and construct validity (Bremner et al., Citation1998). In this study, total scores of subjected-rated CADSS (CADSS-S) were used to measure the severity of dissociation and develop the conceptual model.

The PANSS, HAMD, and CADSS were conducted by three well-trained psychiatrists, with an intra-class correlation coefficient of at least 0.9.

2.3.2. Brief Betrayal Trauma Questionnaire (BBTS)

The BBTS was used to measure the experiences of traumatizing events in this study. The 12-item BBTS was developed to identify traumatic experiences during childhood (<18 years) and adulthood (>18 years), including witnessing a catastrophic event, traffic accident, emotional maltreatment, physical and sexual assault, and natural disasters. The frequency of each experience is score using a three-point Likert scale (never, 1–2 times, >2 times). The BBTS evaluates two levels of betrayal in psychological trauma. High betrayal trauma (HBT), which is defined as betrayal by someone to whom you were very close, and low betrayal trauma (LBT), which is defined as betrayal by someone to whom you were not familiar. In this study, the total score of 10 questions associated with HBT during childhood and adulthood were used to assess the severity of HBT. In addition, the total score of six questions regarding LBT during childhood and adulthood were selected to assess the severity of LBT. The BBTS has been reported to have good reliability and validity (Goldberg & Freyd, Citation2006).

2.3.3. Measure of Parental Style (MOPS)

Parenting style was measured according to the level of parental maltreatment as estimated using the MOPS (Parker et al., Citation1997). The MOPS is a self-reported questionnaire including 30 questions (15 about fathers and 15 about mothers) to measure perceived parental maltreatment. A higher total MOPS score indicates a higher level of parental maltreatment. Maternal and paternal maltreatment were also assessed separately according to total MOPS score for the mother (MOPS-M) and MOPS score for the father (MOPS-F). In this study, MOPS-M and MOPS-F were used to test the conceptual model.

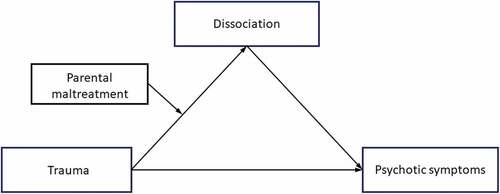

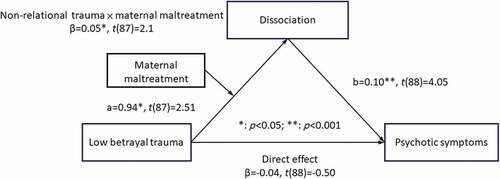

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS version 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the clinical characteristics. To estimate the differences in variables between the patients with MDD and BP, Pearson’s χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables, and the independent t test was for continuous variables. On the other hand, the multiple linear regression was conducted to preliminarily estimate the association between psychotic symptoms and the independent associated factors. The preliminary model was established to initially estimate the association between ‘trauma’ and ‘psychotic symptoms’, which was mediated by ‘dissociation’ (Supplementary Figure 1). If the preliminary model was verified, the final model was developed to confirm our hypothesis. For the final model, we hypothesized that the association between ‘trauma’ and ‘psychotic symptoms’ would be mediated by ‘dissociation’, and the magnitude of the indirect effect would be moderated by ‘parental maltreatment’ (). In order to determine the two models, several variables were analysed. HBT and LBT were alternatively tested to represent ‘trauma’. Paternal maltreatment (MOPS-F) and maternal maltreatment (MOPS-M) were also used, respectively, as the moderator of ‘parental maltreatment’.

To test the preliminary mediation model, the PROCESS macro version developed by Hayes 3.4 (Hayes, Citation2015; Andrew, Citation2018) was used to test the mediation effect. In the PROCESS macro, Hayes’s Model 4 was used to fit the mediation in the preliminary model as shown in Supplementary Figure 1. To further verify the moderated indirect effect, the moderated mediation model was tested using the PROCESS macro based on the hypothesis. The Hayes’s Model 7 was used to fit the moderated mediations in the conceptual model (). The PROCESS macro can perform ordinary least squares regression to estimate the coefficients of the moderated mediation model. All of the quantitative variables were centralized (Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009), and the 95th percentile bootstrap confidence interval (CI) with 5000 bootstrapping samples was estimated. The index of moderated mediation and its 95% CI calculated using the PROCESS macro was used to determine and quantify the statistical significance of the moderated mediation effect (Hayes, Citation2015). If the 95% CI did not include zero then the moderated mediation effect was statistically significant, indicating that the model had been successfully developed. With the significantly moderated mediation effect, conditional indirect effects of parental maltreatment on dissociation were evaluated at three different levels of parental maltreatment, corresponding to the values of mean plus standard deviation (SD), medium, and mean minus SD.

3. Results

3.1. Description of patient variables

A total of 91 patients (59 with MDD and 32 with BP) were recruited, with a mean age of 40.59 ± 7.5 years. Comparisons of continuous and dichotomous variables are listed in . In brief, the dichotomous (sex) and continuous (age, educational level, PANSS-P, HAMD, CADSS-S, MOPS-M, MPOS-F, HBT, LBT) variables were not significantly different in both groups. On the other hand, the reliability measured with Cronbach’s alpha among all measurements were 0.93 (CADSS), 0.63 (HAMD), 0.67 (PANSS), 0.82 (LBT-BBTQ), 0.85 (HBT-BBTQ), and 0.86 (MOPS), respectively.

Table 1. Distribution of all quantitative and dichotomous variables (N = 91)

3.2. Preliminary estimation of predictors and mediation model

In the Supplementary Table 1, the results of multivariate linear regression were presented. It revealed that present higher scores of psychotic symptoms (PANSS-P) were significantly associated with several factors, including higher scores of HBT (standardized coefficients β = 0.21; P = .046), LBT (β = 0.33; P = .002), paternal maltreatment (β = 0.37; P < .001), maternal maltreatment (β = 0.21; P = .047), dissociation (β = 0.47; P < .001), and depression (β = 0.61; P < .001). Regarding the mediation model, HBT and LBT were individually selected into the model to test the mediating effect. We found the statistical significance for indirect effect of 0.09 based on the product terms of the path from HBT to dissociation (β = 1.29, p < .001) and path from dissociation to psychotic symptoms (β = 0.07, p = .003). The direct effect revealed no significance, demonstrating the fully mediating effect of dissociation on the association between HBT and psychotic symptoms (Supplementary Figure 2). Similarly, the statistical significance for indirect effect of 0.13 based on path from LBT to dissociation (β = 1.34, p < .001) and path from dissociation to psychotic symptoms (β = 0.10, p < .001). The direct effect also revealed no significance (Supplementary Figure 3).

3.3. Tests for the moderated mediation model

After testing with trauma (HBT and LBT) and parental maltreatment (MOPS-F and MOPS-M), only one combination fit the conceptual model, indicating that the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms was mediated by dissociation, and that maternal maltreatment (MOPS-M) was the moderator. The remaining combinations did not fit the conceptual model, and the details of least squares regression analyses are presented in Supplementary Table 2 ~ 4.

The results of ordinary least squares regression analysis in the developed model are summarized in and visualized in with estimates of patch and significance. LBT was positively associated with the severity of dissociation (a pathway with β = 0.94, p = .014). The severity of dissociation was also positively correlated with psychotic symptoms (b pathway with β = 0.1, p < .001). The index of moderated mediation was 0.005 with a 95% CI of 0.001 to 0.0012, demonstrating the significantly positive effect of moderation. Taken together, these findings indicated the positive indirect effect of LBT on psychotic symptoms through the positive mediating effect of dissociation, and that a higher level of maternal maltreatment enhanced the effect of LBT with a negative moderating effect.

Table 2. The moderated indirect effect estimated by ordinary least squares regression (Low betrayal trauma and maternal maltreatment)

In order to better understand the moderating effect of maternal maltreatment, the bootstrap indirect effects were estimated for the mediating effect of severity of dissociation at three different levels of maternal maltreatment (mean + SD, mean, mean – SD). The 95% bootstrap CIs showed that the two higher values of maternal maltreatment did not contain zero, while the lower value did (, ). In summary, the moderation effect of maternal maltreatment was confirmed, wherein the mediating effect of dissociation on the relationship between LBT and psychotic symptoms was weaker at higher levels of exposure, indicating the exacerbating effect of maternal maltreatment.

Table 3. Moderated indirect effect of maternal maltreatment on dissociation divided at three level of maternal maltreatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings of the current study

From the result of preliminary model, both LBT and HBT can fit the mediation model with fully mediating effect of dissociation based on the association between HBT or LBT and psychotic symptoms. On the other hand, we found that a higher level of LBT was associated with more severe psychotic symptoms, and that this association was fully mediated by a higher level of dissociation. Moreover, a higher level of maternal maltreatment could moderate the effect of LBT on dissociation. In other words, the results showed the key role of dissociation in the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms, and that maternal maltreatment had a harmful effect on depressive patients with LBT to strengthen the level of dissociation.

4.2. Psychoticism among patients with depressive disorder

Since the psychosis continuum had been proposed in 1994 (Claridge, Citation1994) and elaborated in recent years (Linscott & van Os, Citation2013), research on psychosis focused not only on patients with psychotic disorders but also on subclinical individuals with psychotic-like experiences. However, a specific group of individuals that has been ignored are those with a disturbed psychiatric function but yet reaching a profound decline in reality testing, such as patients with mood disorder as well as psychotic features. A previous meta-analysis demonstrated that both patients with schizophrenia and BP had deficits in cognitive functions although the impairments among patients with BP were less severer than schizophrenia (Nieto & Castellanos, Citation2011). It implies that patients with mood disorder may have less distorted reality or cognitive decline than those with full-blown psychotic disorder. On the other hand, studies assessing delusions multi-dimensionally also found that dimensions of delusional experience, especially distress and preoccupation, are helpful to distinguish psychotic patients from community samples (Sisti et al., Citation2012), indicating the divergences of reality testing between psychotic patients and non-psychotic samples. Therefore, the ‘psychotic symptoms’ that are presented in our study may have aetiological difference from psychotic symptoms in full-blown psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia.

4.3. Mediating effect of dissociation

In addition to the findings of an association between dissociation and psychotic symptoms, we further identified the mediating effect of dissociation on the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms. Previous studies have also reported the mediating effect of dissociation on the relationship between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms among psychotic patients (Cole, Newman-Taylor, & Kennedy, Citation2016; Sun et al., Citation2018), and we further confirmed this mediating effect among patients with MDD and BP. Individuals with psychological trauma may have a diminished sense of self and consequent impairments in reality testing, leading to the formation of psychotic symptoms (Allen, Coyne, & Console, Citation1997; Kilcommons & Morrison, Citation2005). Therefore, the mediating effects of dissociation may potentially be explained by the aforementioned mechanism.

The clinical implication of the mediating effect is that dissociation may play an important role in the association between psychological trauma and psychotic symptoms. Depressive disorder with psychotic features is challengeable for clinicians and healthcare workers for the poor prognosis, morbidity and mortality (Rothschild, Citation2013). It will take more efforts for clinicians in treating with such patients, such as combination therapy (e.g. antidepressants plus antipsychotics) (Wijkstra et al., Citation2015). It is supposed that timely assessment and intervention of dissociation for patients with depressive disorder and traumatic history may be beneficial to prevent from later psychotic symptoms. In other words, an underlying dissociation may remain undetected in patients with affective disorder if clinicians did not assess systematically for dissociation. With early detection of dissociation among patients with depressive disorder, they can be timely treated at an earlier stage. However, it deserves further prospective study to verify this finding.

On the other hand, it should be noticed about the potentially symptomatic overlap between dissociation and psychotic symptoms. Previous study demonstrated the phenomenological overlap between dissociation and psychotic symptoms among patients with schizophrenia (Vogel, Braungardt, Grabe, Schneider, & Klauer, Citation2013). However, another study recruiting non-psychotic samples suggested statistically distinct phenomena between dissociation and psychotic-like symptoms (Humpston et al., Citation2016). Regarding our study, the variance inflation factor in the linear regression between dissociation and psychotic symptoms was estimated at 1.0, indicating no evidence of collinearity (Sheather, Citation2009). Similarly, it also needs further investigations to explore the phenomenological characteristics between dissociation and psychotic symptoms.

4.4. Moderating effect of maternal maltreatment and the effect of LBT on psychotic symptoms

In this study, we confirmed the key role of parenting dysfunction on the mediating effect of dissociation on the relationship between LBT and psychotic symptoms. Parental dysfunction has also been reported to have an impact on dissociation. A previous study found that the level of dissociation was positively associated with parental dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia (Schroeder, Langeland, Fisher, Huber, & Schafer, Citation2016). Another study reported that emotional neglect by parents was related to later symptoms of dissociation (Wright, Crawford, & Del Castillo, Citation2009). On the other hand, disrupted attachment, involving childhood trauma and parental maltreatment, may play an important role in the later development of dissociation (Draijer & Langeland, Citation1999; Lyons-Ruth, Dutra, Schuder, & Bianchi, Citation2006). Disorganized attachment is reported to mediate the association between child sexual abuse and dissociation (Hebert, Langevin, & Charest, Citation2020), and it may also influence in the association between trauma and dissociation. In the current study, only maternal maltreatment had a significantly moderating effect, but not paternal maltreatment. This may be explained by the difference in parenting style between fathers and mothers. Several studies have suggested that Chinese mothers take the main parenting role, and that they are more supportive and responsive than fathers (Shek, Citation2006, Citation2008). A meta-analysis demonstrated that perceived maternal parenting attributes were more positive than perceived paternal parenting attributes among Chinese adolescents (Dou, Shek, & Kwok, Citation2020). Due to the importance of maternal parenting style, maternal maltreatment may cause children serious harm, for which support from fathers may not be able to compensate. However, further investigations are needed to explore the effects of differences in parenting style on psychopathology to clarify this issue.

The effects of psychological trauma on psychotic disorder have been investigated previously (Bebbington et al., Citation2004; Read & Argyle, Citation1999). In the current study, we further examined the effect of different types of traumas. In 1996, Freyd proposed that HBT could be defined as psychological trauma that is perpetrated by someone to whom the victim is familiar or trusts (Freyd, Citation1996). Attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1999) is defined as the nature of humans to keep relationships with others, and as HBT is involved with attachment-based relationships, it is qualitatively different from LBT (Bernstein & Freyd, Citation2014). HBT has also been associated with borderline personality organization (Yalch & Levendosky, Citation2014). Haahr et al. demonstrated that HBT delayed help-seeking behaviours among patients with a first episode of psychosis, resulting in poorer premorbid adjustment and a longer duration of untreated psychosis (Haahr et al., Citation2018). Thus, HBT is more psychologically hazardous than LBT (Bernstein & Freyd, Citation2014). However, after examining both kinds of trauma (HBT and LBT), only LBT fit the moderated mediation model. We hypothesize that this may be due to the relatively stronger psychological impact of HBT (Bernstein & Freyd, Citation2014). According to the results of ordinary least squares regression analysis, the effect of HBT (β = 1.056; p = .001) on dissociation was higher than that of LBT (β = 0.938; p = .014). Therefore, maternal maltreatment may be not strong enough to moderate the association between HBT and dissociation. On the other hand, the insignificance of moderating effect with maternal maltreatment in the association between HBT and dissociation may be confounded by the potentially symptomatic overlap between HBT and maternal maltreatment. Moreover, it may be able to significantly moderate the association between LBT and dissociation due to the relatively lower psychological impact of LBT on developing psychotic symptoms. Further comparative and conceptual studies between HBT and LBT are warranted to clarify this hypothesis.

5. Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the moderating effect of maternal maltreatment on the associations among psychological trauma, dissociation, and psychotic symptoms in patients with MDD and BP. Moreover, the state of psychotic symptoms, depression and dissociation was assessed prospectively by board-certified psychiatrists, which is also a strength of this study. Nevertheless, several limitations need to be addressed. First, the limited number of cases may limit the interpretation of the results. Second, the level of support from parents was not measured. Therefore, further studies are needed to explore whether or not parental support can attenuate the effect of psychological trauma. Third, psychological trauma was self-reported, and it is possible that recall bias may have confounded the results.

Fourth, the data of the current study was collected in a single time point. Therefore, the causality cannot be determined. Finally, we did not control for treatment of the participants, which was personalized according to the clinical judgement of their clinicians rather than being standardized.

6. Conclusion

In the current study, we developed a moderated mediation model, which demonstrated the association between LBT and psychotic symptoms with a mediating effect of dissociation and moderating effect of maternal maltreatment. Our findings indicated that dissociation fully mediated the association between LBT trauma and psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, an increased level of maternal maltreatment may exacerbate the effect of LBT on dissociation, resulting in the enhancement of the full mediation model to develop psychotic symptoms. Clinicians should be aware of depressive patients with a history of LBT and maternal maltreatment due to the risk of developing dissociation and psychotic symptoms. According to these findings, we hypothesize that interventions to prevent maternal maltreatment or enhance parenting skills may protect depressive patients with LBT from developing dissociation and psychotic symptoms. Further studies with a well-controlled design and larger prospective cohort are warranted to verify this hypothesis and extend the applicability and generalizability of the current study.

Authors’ contributions

Dian-Jeng Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Yung-Chi Hsieh: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Chui-De Chiu: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. Ching-Hua Lin: Data curation, Conceptualization. Li-Shiu Chou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - review & editing.

Data availability

The Institutional Review Board of Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital did not approve the authors making the research data publicly available. Readers and all interested researchers may contact Dr. Li-Shiu Chou (Email: [email protected]) for details.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (197.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the assistance of the staff at Kaohsiung Municipal Kai-Syuan Psychiatric Hospital. All authors are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest with respect to this research study and paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, J. G., Coyne, L., & Console, D. A. (1997). Dissociative detachment relates to psychotic symptoms and personality decompensation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 38(6), 327–11. doi:10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90928-7

- Bebbington, P. E., Bhugra, D., Brugha, T., Singleton, N., Farrell, M., Jenkins, R., … Meltzer, H. (2004). Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage: Evidence from the second British national survey of psychiatric morbidity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185(3), 220–226. doi:10.1192/bjp.185.3.220

- Bernstein, R., & Freyd, J. (2014). Trauma at home: How betrayal trauma and attachment theories understand the human response to abuse by an attachment figure. Attachment: New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 8, 18–41. 10.1258/1.662.343

- Bowlby, J. (1999). Attachment and loss (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

- Bremner, J. D., Krystal, J. H., Putnam, F. W., Southwick, S. M., Marmar, C., Charney, D. S., & Mazure, C. M. (1998). Measurement of dissociative states with the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(1), 125–136. doi:10.1023/A:1024465317902

- Catalan, A., Angosto, V., Diaz, A., Valverde, C., de Artaza, M. G., Sesma, E., … Gonzalez-Torres, M. A. (2017). Relation between psychotic symptoms, parental care and childhood trauma in severe mental disorders. Psychiatry Research, 251, 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.017

- Cernis, E., Evans, R., Ehlers, A., & Freeman, D. (2021). Dissociation in relation to other mental health conditions: An exploration using network analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 460–467. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.08.023

- Claridge, G. (1994). Single indicator of risk for schizophrenia: Probable fact or likely myth? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 20(1), 151–168. doi:10.1093/schbul/20.1.151

- Cole, C. L., Newman-Taylor, K., & Kennedy, F. (2016). Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and subclinical psychosis. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(5), 577–592. doi:10.1080/15299732.2016.1172537

- de Sousa, P., Varese, F., Sellwood, W., & Bentall, R. P. (2014). Parental communication and psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 40(4), 756–768. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt088

- Dou, D., Shek, D. T. L., & Kwok, K. H. R. (2020). Perceived paternal and maternal parenting attributes among Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8741. doi:10.3390/ijerph17238741

- Draijer, N., & Langeland, W. (1999). Childhood trauma and perceived parental dysfunction in the etiology of dissociative symptoms in psychiatric inpatients. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(3), 379–385. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.3.379

- Forty, L., Jones, L., Jones, I., Cooper, C., Russell, E., Farmer, A., … Craddock, N. (2009). Is depression severity the sole cause of psychotic symptoms during an episode of unipolar major depression? A study both between and within subjects. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1–3), 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.012

- Freeman, D., & Fowler, D. (2009). Routes to psychotic symptoms: Trauma, anxiety and psychosis-like experiences. Psychiatry Research, 169(2), 107–112. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.07.009

- Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press.

- Goldberg, L. R., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: Gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(3), 39–63. doi:10.1300/J229v07n03_04

- Haahr, U. H., Larsen, T. K., Simonsen, E., Rund, B. R., Joa, I., Rossberg, J. I., … Melle, I. (2018). Relation between premorbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis and close interpersonal trauma in first-episode psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12(3), 316–323. doi:10.1111/eip.12315

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Hebert, M., Langevin, R., & Charest, F. (2020). Disorganized attachment and emotion dysregulation as mediators of the association between sexual abuse and dissociation in preschoolers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 267, 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.032

- Holshausen, K., Bowie, C. R., & Harkness, K. L. (2016). The relation of childhood maltreatment to psychotic symptoms in adolescents and young adults with depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(3), 241–247. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.952010

- Humpston, C. S., Walsh, E., Oakley, D. A., Mehta, M. A., Bell, V., & Deeley, Q. (2016). The relationship between different types of dissociation and psychosis-like experiences in a non-clinical sample. Consciousness and Cognition, 41, 83–92. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2016.02.009

- Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A., & Opler, L. A. (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 13(2), 261–276. doi:10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

- Kilcommons, A. M., & Morrison, A. P. (2005). Relationships between trauma and psychosis: An exploration of cognitive and dissociative factors. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 351–359. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00623.x

- Linscott, R. J., & van Os, J. (2013). An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: On the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychological Medicine, 43(6), 1133–1149. doi:10.1017/S0033291712001626

- Lyons-Ruth, K., Dutra, L., Schuder, M. R., & Bianchi, I. (2006). From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: Relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 63–86, viii. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.011

- McCreadie, R. G., Williamson, D. J., Athawes, R. W., Connolly, M. A., & Tilak-Singh, D. (1994). The Nithsdale Schizophrenia Surveys. XIII. Parental rearing patterns, current symptomatology and relatives’ expressed emotion. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 347–352. doi:10.1192/bjp.165.3.347

- Monteleone, A. M., Ruzzi, V., Patriciello, G., Pellegrino, F., Cascino, G., Castellini, G., … Maj, M. (2020). Parental bonding, childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: An investigation of their interactions. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25(3), 577–589. doi:10.1007/s40519-019-00649-0

- Morgan, C., & Fisher, H. (2007). Environment and schizophrenia: Environmental factors in schizophrenia: Childhood trauma–a critical review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(1), 3–10. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl053

- Nieto, R. G., & Castellanos, F. X. (2011). A meta-analysis of neuropsychological functioning in patients with early onset schizophrenia and pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2), 266–280. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.546049

- Parker, G., Fairley, M., Greenwood, J., Jurd, S., & Silove, D. (1982). Parental representations of schizophrenics and their association with onset and course of schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 141(6), 573–581. doi:10.1192/bjp.141.6.573

- Parker, G., Roussos, J., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Mitchell, P., Wilhelm, K., & Austin, M. P. (1997). The development of a refined measure of dysfunctional parenting and assessment of its relevance in patients with affective disorders. Psychological Medicine, 27(5), 1193–1203. Retrieved from 10.2356/93005.23

- Read, J., & Argyle, N. (1999). Hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder among adult psychiatric inpatients with a history of child abuse. Psychiatric Services, 50(11), 1467–1472. doi:10.1176/ps.50.11.1467

- Read, J., van Os, J., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: A literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330–350. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x

- Rothschild, A. J. (2013). Challenges in the treatment of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(4), 787–796. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt046

- Schiavone, F. L., McKinnon, M. C., & Lanius, R. A. (2018). Psychotic-Like Symptoms and the Temporal Lobe in Trauma-Related Disorders: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Assessment of Potential Malingering. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 2, 2470547018797046. doi:10.1177/2470547018797046

- Schroeder, K., Langeland, W., Fisher, H. L., Huber, C. G., & Schafer, I. (2016). Dissociation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: What is the role of different types of childhood adversity? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 68, 201–208. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.04.019

- Sheather, S. J. (2009). A modern approach to regression with R. New York; London: Springer.

- Shek, D. T. L. (2006). Perceived parental behavioral control and psychological control in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 34(2), 163–176. doi:10.1080/01926180500357891

- Shek, D. T. L. (2008). Perceived parental control and parent–child relational qualities in early adolescents in Hong Kong: Parent gender, child gender and grade differences. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 58(9–10), 666–681. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9371-5

- Shin, S. H., Wang, X., Yoon, S. H., Cage, J. L., Kobulsky, J. M., & Montemayor, B. N. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and alcohol-related problems in young adulthood: The protective role of parental warmth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104238. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104238

- Sisti, D., Rocchi, M. B., Siddi, S., Mura, T., Manca, S., Preti, A., & Petretto, D. R. (2012). Preoccupation and distress are relevant dimensions in delusional beliefs. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(7), 1039–1043. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.02.005

- Sun, P., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Simpson, K., Lawrence, K., Peach, N., & Bendall, S. (2018). Does dissociation mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucinations, delusions in first episode psychosis? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 84, 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.04.004

- Tonna, M., De Panfilis, C., & Marchesi, C. (2012). Mood-congruent and mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms in major depression: The role of severity and personality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2–3), 464–468. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.017

- Varese, F., Udachina, A., Myin‐Germeys, I., Oorschot, M., & Bentall, R. P. (2011). The relationship between dissociation and auditory verbal hallucinations in the flow of daily life of patients with psychosis. Psychosis, 3(1), 14–28. doi:10.1080/17522439.2010.548564

- Vogel, M., Braungardt, T., Grabe, H. J., Schneider, W., & Klauer, T. (2013). Detachment, compartmentalization, and schizophrenia: Linking dissociation and psychosis by subtype. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 14(3), 273–287. doi:10.1080/15299732.2012.724760

- Wijkstra, J., Lijmer, J., Burger, H., Cipriani, A., Geddes, J., & Nolen, W. A. (2015). Pharmacological treatment for psychotic depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (7), CD004044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004044.pub4

- Williams, J. B. (1988). A structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45(8), 742–747. Retrieved from 10.2585/339.5203

- Willinger, U., Heiden, A. M., Meszaros, K., Formann, A. K., & Aschauer, H. N. (2002). Maternal bonding behaviour in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, considering premorbid personality traits. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(5), 663–668. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01038.x

- Wright, M. O., Crawford, E., & Del Castillo, D. (2009). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 59–68. doi:10.1192/bjp.185.3.220

- Wu, B. J., Lan, T. H., Hu, T. M., Lee, S. M., & Liou, J. Y. (2015). Validation of a five-factor model of a Chinese Mandarin version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (CMV-PANSS) in a sample of 813 schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research, 169(1–3), 489–490. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.09.011

- Yalch, M. M., & Levendosky, A. A. (2014). Betrayal trauma and dimensions of borderline personality organization. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(3), 271–284. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.017