ABSTRACT

Background

Climate change is having significant impacts on health and mental health across Europe and globally. Such effects are likely to be more severe in climate change hotspots such as the Mediterranean region, including Italy.

Objective

To review existing literature on the relationship between climate change and mental health in Italy, with a particular focus on trauma and PTSD.

Methods

A scoping review methodology was used. We followed guidance for scoping reviews and the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist. We searched for literature in MEDLINE, Global Health, Embase and PsycINFO. Following screening, data was extracted from individual papers and a quality assessment was conducted. Given the heterogeneity of studies, findings were summarized narratively.

Results

We identified 21 original research articles investigating the relationship between climate change and mental health in Italy. Climate change stressors (heat and heatwaves in particular) were found to have several negative effects on various mental health outcomes, such as a higher risk of mortality among people with mental health conditions, suicide and suicidal behaviour and psychiatric morbidity (e.g. psychiatric hospitalization and symptoms of mental health conditions). However, there is little research on the relationship between climate change and trauma or PTSD in the Italian context.

Conclusions

More attention and resources should be directed towards understanding the mental health implications of climate change to prevent, promote, and respond to the mental health needs of Italy and the wider Mediterranean region.

HIGHLIGHTS

• Climate change stressors in Italy were found to have detrimental impacts on various mental health outcomes, such as psychiatric mortality and morbidity. • Little research on the relationship between climate change stressors and PTSD exists in Italy.

Antecedentes: El cambio climático está teniendo un impacto significativo en la salud y la salud mental en Europa y a nivel mundial. Es probable que tales efectos sean más severos en los puntos críticos del cambio climático, como la región del Mediterráneo, incluida Italia.

Objetivo: Revisar la literatura existente sobre la relación entre el cambio climático y la salud mental en Italia, con un enfoque particular en trauma y TEPT.

Métodos: Se utilizó una metodología de revisión del alcance. Seguimos la guía para las revisiones de alcance y la lista de verificación de la Extensión PRISMA para las Revisiones de Alcance (PRISMA-ScR). Se realizaron búsquedas de literatura en MEDLINE, Global Health, Embase y PsycINFO. Después de la selección, se extrajeron los datos de los artículos individuales y se realizó una evaluación de calidad. Dada la heterogeneidad de los estudios, los resultados se resumieron de forma narrativa.

Resultados: Identificamos 21 artículos de investigación originales que investigan la relación entre el cambio climático y la salud mental en Italia. Se encontró que los factores estresantes del cambio climático (el calor y las olas de calor en particular) tienen varios efectos negativos en varios resultados de salud mental, como un mayor riesgo de mortalidad entre las personas con afecciones de salud mental, suicidio y comportamiento suicida, y morbilidad psiquiátrica (p. ej., hospitalización psiquiátrica y síntomas de trastornos de salud mental). Sin embargo, hay poca investigación sobre la relación entre el cambio climático y el trauma o el TEPT en el contexto italiano.

Conclusiones: Se debe dirigir más atención y recursos hacia la comprensión de las implicancias del cambio climático en la salud mental para prevenir, promover y responder a las necesidades de salud mental de Italia y la región mediterránea en general.

背景: 气候变化正在对整个欧洲和全球的健康和心理健康产生重大影响。在包括意大利在内的地中海地区等气候变化热点地区,这种影响可能更为严重。

目的: 综述意大利气候变化与心理健康之间关系的现有文献,特别关注创伤和 PTSD。

方法: 使用范围综述方法。我们遵循范围综述指南和 PRISMA 范围综述扩展 (PRISMA-ScR) 清单。我们检索了 MEDLINE、Global Health、Embase 和 PsycINFO 中的文献。筛选后,从单篇论文中提取数据并进行质量评估。鉴于研究的异质性,叙述性地总结了研究结果。

结果: 我们确定了 21 篇原创研究文章,考查意大利气候变化与心理健康之间的关系。气候变化应激源(尤其是热浪和热浪)被发现对各种心理健康结果有一些负面影响,例如患有心理健康病症的人有更高的死亡风险、自杀和自杀行为以及精神疾病病况(例如,因精神病住院和心理健康病症的症状)。然而,在意大利背景下,关于气候变化与创伤或 PTSD 之间关系的研究很少。

结论: 应将更多的关注和资源用于了解气候变化对心理健康的影响,以预防、促进和应对意大利和更广泛地中海地区的心理健康需求。

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Climate change is having widespread health impacts in Europe and across the world. According to the Lancet Countdown in Europe, climate change is already affecting health across the European region through more frequent and extreme weather events, changes in the environmental suitability for infectious diseases, and alterations to water and food systems (Romanello et al., Citation2021a). Rising temperatures have led to increasingly intense heatwaves over the past decades in Europe, such as the 2003 heatwave which has been linked to 70,000 excess deaths in Europe (Robine et al., Citation2008). It has been estimated that one out of three deaths related to heat in Europe between 1990 and 2018 can be attributable to anthropogenic global warming (Vicedo-Cabrera et al., Citation2021). These impacts are in line with the global consequences of climate change on human health (Romanello et al., Citation2021b).

Despite widespread attention to the physical health impacts of climate change in Europe, less attention has been paid to its mental health consequences. This reflects a general trend in the literature on the topic (Charlson et al., Citation2021; Romanello et al., Citation2021b). Nonetheless, there is a growing body of evidence linking climate change and mental health worldwide (Lawrance, Thompson, Fontana, & Jennings, Citation2021). Across multiple countries both in and outside of Europe, a variety of climate change stressors have been associated with several worsened mental health outcomes from heightened symptoms of mental health problems to increased mortality and hospitalization rates among people with pre-existing mental health conditions (see Charlson et al., Citation2021 for a review of the global evidence on climate change and mental health). Climate change stressors have also been linked to trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder, for example by making exposure to trauma via extreme weather events more widespread (Augustinavicius et al., Citation2021).

Within the European context, the Mediterranean region has been deemed particularly vulnerable to climate change with the region being considered a climate change ‘hotspot’ and warming 20% faster than the global average (UNEP, Citation2020). This is reflected in the Mediterranean region being more at risk of heat-related health issues than other European regions (Kendrovski et al., Citation2017). Italy specifically is vulnerable to several climate change-related stressors; due to its heterogeneous geographical conformation spanning multiple types of habitats and local climates, these include heatwaves, floods, landslides, wildfires, sea-level rise, coastal erosion, droughts and water stress, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, desertification, and ice melt and avalanches.

In recent years, Italy has been particularly affected by climate change events. On Wednesday 11th of August 2021, one of the highest temperatures (48.8°) ever registered in Europe was recorded in the south of Italy (Pianigiani, Citation2021). Similarly, according to the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), Italy was the European country with the highest number of recorded wildfires and largest burnt areas in 2021 (EFFIS, Citation2021). When considering the impact of climate change on the Italian population, one needs to consider other concomitant factors, such as the high prevalence of elderly people (who are more vulnerable to heat and heatwaves), the economic reliance on agriculture and tourism – highly sensitive to climate change – and the high risk of other natural hazards such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

However, despite the relevance of climate change for this geographical area, there is little research specific to Italy or to the Mediterranean region on mental health and climate change (Aguglia et al., Citation2019; Di Giorgi, Michielin, & Michielin, Citation2020; Di Nicola et al., Citation2020; Oudin Åström et al., Citation2015; Preti, Lentini, & Maugeri, Citation2007; Rotgé, Fossati, & Lemogne, Citation2014). This is again in contrast with the attention given to physical health (Ministero della Salute, Citation2019; World Health Organization, Citation2018).

In this paper, we aim to provide a review of the original research literature on the relationship between climate change stressors and mental health in Italy. When available, we will provide information on trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Augustinavicius et al., Citation2021). While this paper uses Italy as a case study, many of the findings are likely to apply to several European countries within the Mediterranean region with similar risks and vulnerabilities such as Greece, Spain, Croatia, and Albania or to the Middle East and North Africa region. The ultimate objective of the current paper is to encourage more research and policy action on the intersection between climate change and mental health in Italy and the wider Mediterranean region.

2. Methods

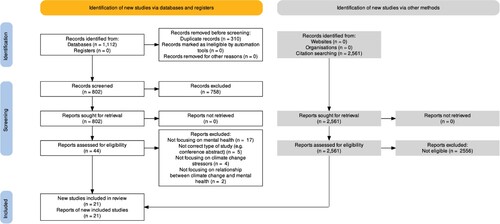

The review followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018) (see for PRISMA-ScR checklist). We used the Joanna Briggs Institute manual for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020) as methodological guidance. To identify original research on mental health, trauma and climate change in Italy the following online databases were accessed and searched via Ovid: MEDLINE, Global Health, Embase and PsycINFO. The search was conducted on the 1st of October 2021 and any papers published up to that date were included (no restriction was made for publication date). The search strategy covered three broad categories: (i) climate change and climate change stressors (search adapted from Berrang-Ford et al., Citation2021); (ii) mental health (including trauma and PTSD) and (iii) Italy (including all Italian regions with both English and Italian spelling). The complete search strategy is reported in . Additional studies were identified through backward and forward citation of all included studies using Google Scholar.

Following automatic removal of duplicates on Ovid, all articles identified were imported into Rayyan (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, Citation2016), where additional duplicates were manually removed. On Rayyan, the first author (AM) conducted an initial screening of abstract and titles, followed by full-text screening. If papers were not available in the public domain (n = 2), the authors were contacted to obtain a copy. Papers were screened against a set of pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (see a detailed description of criteria in ).

A standardized data charting sheet was created in Excel to extract relevant information from the selected studies. The table included author information, publication year, language, location in which study was conducted (city and region when available), time span of data collection, study design, type of analysis (i.e. qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), study population, sample size, climate change exposure, mental health outcome, key findings, and mention of trauma or PTSD (conducted by systematically searching the document for ‘trauma’, ‘PTSD’, ‘DPTS’, ‘post-traumatic’, ‘posttraumatic’). Data was extracted by one author (AM).

The methodological quality of all studies was assessed using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Case–Control Studies and the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Institute of Health, Citation2021). Studies were rated as being either ‘poor’, ‘fair’, or ‘good’ guided by the questions posed by the quality assessment tools. Studies of all qualities were included in the review due to the exploratory nature of scoping reviews.

Due to the heterogeneity of findings, quantitative data was synthesized narratively rather than through meta-analytic techniques. Characteristics of all studies were summarized in tabular form. Additionally, studies are summarized in text by clustering them according to type of climate exposure (i.e. temperature, extreme weather events, and general climate change). The PRISMA flow diagram was created using PRISMA 2020: R package and ShinyApp for making PRISMA 2020 flow diagrams (Haddaway et al., Citation2022).

3. Results

We identified 21 original studies focusing on the relationship between climate change and mental health in Italy (see PRISMA flow chart below in ). The search produced 1112 results, of which 310 were duplicates and 802 underwent title and abstract screening. This process led to the exclusion of 758 papers and left 44 papers for full-text review against our eligibility criteria. This led to the identification of 16 papers that qualified for our review. Reasons for the exclusion of the 28 papers are shown in . A list of the studies excluded after full-text screening with individual reason for exclusion is reported in . Screening 2561 papers through forward and backward citation of the eligible studies identified an additional 5 papers.

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

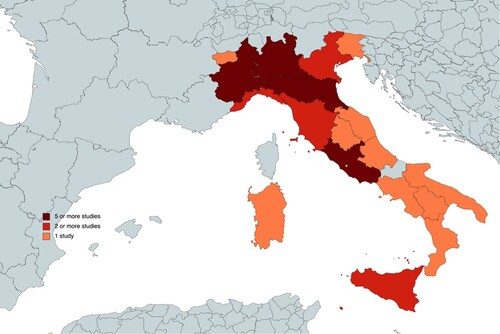

Detailed information on each study is provided in . The oldest paper had been published in 1997 and the most recent in 2021. Most papers (n = 19) had been published in English with only two papers being published in Italian. In terms of geographical distribution (see ), most studies had been conducted in the Northern regions of Italy (i.e. Piemonte, n = 7; Emilia Romagna, n = 5, Lombardia, n = 5) or in the region of the capital city Rome (i.e. Lazio, n = 7). Some studies had also been conducted in Tuscany (n = 4), Sicily, (n = 2), Veneto (n = 2) and Liguria (n = 2). All other regions had been studied only once. Four studies focused on the entire of Italy. No study had been conducted in the Molise and Trentino-Alto Adige regions.

Figure 2. Geographical location of included studies. Latium = 7, Piedmont = 7, Emilia-Romagna = 5, Tuscany = 4, Sicily = 2, Veneto = 2, Liguria = 2, Calabria = 1, Sardinia = 1, Basilicata = 1, Campania = 1, Apuglia = 1, Abruzzo = 1, Marche = 1, Umbria = 1, Friuli-Venezia Giulia = 1, Aosta Valley = 1.

In terms of study design, most studies had a cross-sectional, repeated cross-sectional, or time-series study design (n = 13), and a minority had a case-crossover design (n = 4), a case–control design (n = 2) or a cohort study design (n = 2). All studies used quantitative analysis, except for one study that used mixed methods. In terms of climate change exposure, most studies focused on temperature (often using temperature together with another environmental variable such as humidity to calculate a heat index or to determine heatwave periods) (n = 17), with a minority of studies focusing on exposure to floods or risk of floods (n = 3), and one paper focusing on general perception of climate change (see for more precise description of exposure in each study). Conversely, in terms of outcomes, the most common outcome was mortality among patients with mental health conditions (n = 7), followed by death by suicide and suicide attempts (n = 6), symptoms of mental health conditions (e.g. PTSD, depression, anxiety) (n = 3), psychiatric hospitalizations or psychiatric visits to the emergency department (n = 3), and other outcomes (e.g. worry in relation to future floods or emergency calls for mental health conditions) (n = 2).

3.2. Relationship between climate change exposure and mental health

The relationships identified between climate change exposure and mental health outcome are presented below. Results are presented separately for different types of climate change exposures.

3.3. Temperature

Most studies focused on the relative risk of mortality among people with mental health conditions exposed to heat or heatwaves. Most of these studies found that people with mental health conditions are at higher risk of mortality than the general population when exposed to heat or heatwaves. One case-crossover study conducted on deaths registered in three Italian cities found that, in all cities, people with previous mental health conditions (i.e. depression and psychosis), were at higher risk of dying during hot days (de’Donato et al., Citation2008). Similarly, a time-series study on cause-specific mortality in four Italian cities illustrated how the greatest excess mortality as a result of the 2003 heatwave was observed for central nervous system, circulatory, and respiratory diseases and metabolic/endocrine and psychological illnesses (Michelozzi et al., Citation2005). One cohort study focusing on heat wave-related mortality among older adults in Rome found higher risk of dying among those previously hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder (Schifano et al., Citation2009). Another case-crossover study also focusing on older adults exposed to high temperatures when in care facilities in four Italian cities found that psychiatric disorders were among the most important effect modifiers in the relationship between heat exposure and death (OR = 2.05; 1.44–2.93) (Stafoggia et al., Citation2008). One other case-crossover study by the same author in the same context (but focusing on the general adult population) also identified previous psychiatric disorders as effect modifiers (OR = 1.69; 1.39–2.07) (Stafoggia et al., Citation2006). An additional study conducted in Bologna also identified the highest probability of dying due to an increase in temperature among patients with depression and cognitive decline (Stivanello et al., Citation2020). Only one cohort study failed to find evidence for increased mortality among susceptible subgroups (including participants with psychiatric disorders) during heatwaves in Rome (despite finding increased risk for the psychiatric subgroup in Stockholm) (Oudin Åström et al., Citation2015).

Another common mental health outcome considered in relation to temperature was suicide (including both suicide attempts and death by suicide). One time-series study using national data on suicide and suicide attempts spanning 1974–1994 identified a significant positive relationship between the mean monthly distribution of deaths by suicide and the mean monthly values of temperature (both maximum and minimum) (Preti, Citation1997). A similar time-series study collected data from the same period from 17 Italian towns in different regions but found a negative relationship between deaths by suicide with mean yearly temperature values (both maximum and minimum). Two time-series studies using national data on suicide and suicide attempts between 1984 and 1995 showed a significant positive relationship of higher temperature with violent suicides (Preti & Miotto, Citation1998) and suicide attempts (Preti & Miotto, Citation2000), particularly among males. One subsequent time-series study using a similar approach with national suicide data spanning approximately 30 years from 1974 to 2003 also found that increasing anomalies in monthly average temperatures were associated, among males, with a higher monthly suicide mean from May to August and to a lesser extent in November and December (but a reverse relationship was identified for January and inconsistent findings were reported for females) (Preti et al., Citation2007). Finally, one time-series study conducted in Genova (Liguria), noted a peak in hospitalizations for suicide attempts (SA) that was typically found in late spring and early summer and attributed by the authors to global warming (Giacomini et al., Citation2022). The authors however did not find a statistically significant increase in the number of SA cases between 2013 and 2018. Overall, these studies seem to indicate preliminary evidence for the association between higher temperatures with deaths by suicide and suicide attempts. However, the evidence remains mixed with possible differential impacts between males and females identified in one study and ambiguity concerning the impact of seasonality versus that of climate in certain studies.

A few additional mental health outcomes were considered in the context of heat and temperature. Two case–control studies using data from psychiatric hospitalization in Orbassano (Piedmont) from 2003 to 2005 identified an association between admission of patients with bipolar disorder (compared to patients admitted with other diagnoses) with maximum temperature (Aguglia et al., Citation2019) as well as a significant association between maximum and medium temperature with involuntary psychiatric admissions (Aguglia et al., Citation2020). Another study focusing on psychiatric visits to emergency units in Messina (Sicily) between 2005 and 2010 reported mixed findings concerning the correlation between temperature with anxiety, mood disorders, and psychosis in different seasons (Settineri et al., Citation2016). Finally, a time-series study using data on emergency calls in Florence (Tuscany) between June and August 2005 reported an association between the hottest conditions and increases in calls specifically for psychiatric conditions, when considering the entire summer period (Petralli et al., Citation2012).

3.4. Extreme weather events

Three studies focused on floods with two studies focusing on individuals directly exposed to floods in Cardoso (Tuscany) and one study focusing on individuals living in an area at risk of flooding in the Aosta Valley. Of the two studies on direct flood exposure, one cross-sectional study focused on disaster rescue squads (N = 34) and identified, 7 years following the flood, 11.8% of the sample as having full PTSD, 11.8% as having subthreshold PTSD with impairment, and 17.6% has having subthreshold PTSD without impairment (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2004). The other cross-sectional study focused on disaster survivors (N = 61) 8 years following the flood and reported that 45.9% of the sample had full PTSD, 35.8% had subthreshold PTSD, and 21.3% had no PTSD (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2005). Finally, one cross-sectional study focused on worry about possible future floods and landslides in at risk communities (N = 407) and found that people were particularly worried about harm to oneself and loved ones and that there was a positive correlation between level of worry and degree of preventative behaviours implemented (Miceli et al., Citation2010).

3.5. Climate change perceptions

One cross-sectional study focused on migrants (N = 100) from African countries in Italy (countries with high or extreme vulnerability to climate change) and identified a significant but weak association (r = 0.23) between perception of climate change and emotional disorders (Di Giorgi et al., Citation2020).

3.6. Trauma and PTSD

When systematically searching through the included papers, only four papers (19% of all papers) mentioned trauma and/or PTSD. Of these, only two studies collected original data on PTSD (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2004, Citation2005). In one study (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2004) PTSD diagnosis was assessed using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV and in both studies (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2004, Citation2005) PTSD symptoms were assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale. The remaining two studies (Di Giorgi et al., Citation2020; Giacomini et al., Citation2022) mentioned trauma as one of the negative consequences of climate change on mental health in their introductions. The findings from these four studies are summarized in the sections above.

3.7. Quality of studies

Most studies were deemed to be of ‘fair’ quality (n = 13), with five studies being rated as ‘good’ and three as ‘poor’. Common methodological issues included: not controlling for possible confounders, poor measurements of the climate change exposure or of the mental health outcome, and no discussions around statistical power. More precise information on the quality assessment can be found in .

4. Discussion

This represents the first review to outline the original literature on the relationship between climate change and mental health in Italy. We identified 21 original studies highlighting the negative impacts that climate change is having on mental health. The most robust finding was the increased risk of death among people with mental health conditions when exposed to anomalously high temperature and heatwaves. This finding is in line with existing literature from other European countries, like the United Kingdom (Page et al., Citation2012) and Sweden (Rocklöv et al., Citation2014), as well as with the global literature (Charlson et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2021).

Various studies also seemed to indicate a relationship between heat and suicide (both suicide attempts and death by suicide). Evidence from other European countries such as Germany (Müller et al., Citation2011) and the UK (Page et al., Citation2007) also identified a positive association between higher environmental temperatures and suicidal behaviour (but see work by Helama et al., Citation2013 on the effect of suicide prevention policy in mitigating this relationship in Finland). However, not all reviewed studies found a positive relationship between heat and suicide. This is in line with global evidence showing mixed findings concerning the relationship between ambient temperature and suicide (Florido Ngu et al., Citation2021; Kim et al., Citation2019). Other studies in our review identified heat and heatwaves as being associated with mental health morbidity (e.g. admission to psychiatric hospital, emergency calls for psychiatric conditions, psychiatric visits to the emergency unit). This again is consistent with findings from other European countries such as Portugal (Almendra et al., Citation2019) and Sweden (Carlsen et al., Citation2019).

In terms of extreme weather events, a small number of studies focused on the detrimental impact of floods on mental health (particularly in relation to PTSD). This is line with substantial evidence on the negative consequences of floods on mental health in other European countries such as the UK (French et al., Citation2019) and Spain (Fontalba-Navas et al., Citation2017). The lack of evidence on other types of extreme weather events such as wildfires was surprising, especially given the widespread nature of wildfires in Italy and evidence from other European countries such as Greece (Adamis et al., Citation2011) and Spain (Caamano-Isorna et al., Citation2011). Future research should attempt to address this research gap by investigating the impact on mental health of other extreme weather events such as wildfires, storms, landslides and avalanches. Given the strong tradition of research on mental health and disasters such as earthquakes in Italy (Chierzi et al., Citation2014; Stratta et al., Citation2016), Italian researchers and academic institutions are well-placed to address this gap in the evidence.

Another surprising aspect of this review is the dearth of research explicitly focusing on climate change and trauma or PTSD, except for two studies on floods (Di Fiorino et al., Citation2004, Citation2005). However, despite the lack of primary evidence, various associations likely exist between the topics covered in the reviewed literature and traumatic stress (Augustinavicius et al., Citation2021). For example, exposure to highly stressful experiences such as the sudden and unexpected death by suicide of a family member or an involuntary psychiatric admission may in certain situations qualify as exposure to trauma and constitute a risk factor for PTSD (Martinaki et al., Citation2021; Mitchell & Terhorst, Citation2017). While robust evidence exists on the association between disasters such as floods and PTSD (Neria et al., Citation2008), future research should investigate the link between trauma and PTSD with a broader range of climate change stressors (e.g. droughts, heatwaves) as well as the possible interaction between the mental health consequences of climate change (e.g. higher psychiatric hospitalizations due to heat) and trauma.

The current paper has several practical implications for Italy and for European countries with similar geographical profiles. For example, since 2005 Italy has established a heat health watch warning system (HHWWS) which can predict up to 3 days in advance weather conditions which might pose a public health threat in 27 cities (Ministero della Salute, Citation2019). As part of this warning system, people with mental health conditions are considered an at-risk population. The current findings support this and highlight the importance for public health messaging to target this population group during heatwaves and for resources to be directed towards their protection. This is likely to apply to other European countries (16 of which have a heat-health warning system), especially those with geographical characteristics similar to Italy such as Greece and Spain (Casanueva et al., Citation2019). In general, this paper highlights the need for more consideration to the mental health impacts of climate change stressors in Italy and in the Mediterranean region in general with a focus on prevention, promotion, and response in both policy, research, and clinical practice (e.g. raising awareness among health professionals about mental health impacts of adverse climatic events).

The current paper also holds several limitations. Various papers presented a range of methodological shortcomings such as not controlling for possible confounders as well as flaws in the measurement of climate change exposure and mental health. While these methodological issues are common in the general climate change and mental health literature (Massazza et al., Citationn.d.), they indicate the need for our results to be interpreted cautiously. Another limitation is the dearth of research on the Southern region of Italy despite this region being more likely to experience certain climatic stressors (e.g. heatwaves), indicating that some results might not be generalizable to the whole country. Additionally, the high heterogeneity of climate change exposures (from heat to extreme weather events) makes aggregating the evidence on climate change complex given that different types of exposures may be more likely to result in different types of outcomes (e.g. extreme weather events such as floods being more likely to result in PTSD than other types of chronic and slow-creeping exposures). Following examples from other reviews, we decided to address this issue by summarizing findings according to the type of exposure (Charlson et al., Citation2021; Cianconi et al., Citation2020). Finally, in certain studies, the distinction between climate, weather, and seasonality was often not clarified by the authors.

Climate change is already having substantial impacts on health across the European context. This review highlights how these impacts include mental health consequences as well, using Italy as a case study. As temperatures and other climate change stressors increase in intensity and frequency across the European continent, it is paramount to understand the pathways linking climate change to mental health and to identify possible responses to protect psychological wellbeing and respond to growing mental health needs. As the Mediterranean region will be at the forefront of this challenge, this paper represents a first step in this direction.

Author contributions

AM and VA conceptualized the study. AM conducted the scoping review and drafted the manuscript. VA and REF commented on the manuscript.

Data availability statement

All extracted data are reported in .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamis, D., Papanikolaou, V., Mellon, R. C., & Prodromitis, G. (2011). The impact of wildfires on mental health of residents in a rural area of Greece. A case control population based study. European Psychiatry, 26(S2), 1188–1188. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(11)72893-0

- Aguglia, A., Serafini, G., Escelsior, A., Amore, M., & Maina, G. (2020). What is the role of meteorological variables on involuntary admission in psychiatric ward? An Italian cross-sectional study. Environmental Research, 180, 108800. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2019.108800

- Aguglia, A., Serafini, G., Escelsior, A., Canepa, G., Amore, M., & Maina, G. (2019). Maximum temperature and solar radiation as predictors of bipolar patient admission in an emergency psychiatric ward. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1140. doi:10.3390/ijerph16071140

- Almendra, R., Loureiro, A., Silva, G., Vasconcelos, J., & Santana, P. (2019). Short-term impacts of air temperature on hospitalizations for mental disorders in Lisbon. The Science of the Total Environment, 647, 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.337

- Augustinavicius, J., Lowe, S., Massazza, A., Hayes, K., Denckla, C., White, R., … Berry, H. L. (2021). Global Climate Change and Trauma: An International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Briefing Paper. https://istss.org/public-resources/istss-briefing-papers/briefing-paper-global-climate-change-and-trauma.

- Berrang-Ford, L., Sietsma, A. J., Callaghan, M., Minx, J. C., Scheelbeek, P. F. D., Haddaway, N. R., … Dangour, A. D. (2021). Systematic mapping of global research on climate and health: A machine learning review. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(8), e514–e525. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00179-0

- Caamano-Isorna, F., Figueiras, A., Sastre, I., Montes-Martínez, A., Taracido, M., & Piñeiro-Lamas, M. (2011). Respiratory and mental health effects of wildfires: An ecological study in galician municipalities (north-west Spain). Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 10, 48. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-10-48

- Carlsen, H. K., Oudin, A., Steingrimsson, S., & Oudin Åström, D. (2019). Ambient temperature and associations with daily visits to a psychiatric emergency unit in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 2. doi:10.3390/ijerph16020286

- Casanueva, A., Burgstall, A., Kotlarski, S., Messeri, A., Morabito, M., Flouris, A. D., … Schwierz, C. (2019). Overview of existing heat-health warning systems in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2657. doi:10.3390/ijerph16152657

- Charlson, F., Ali, S., Benmarhnia, T., Pearl, M., Massazza, A., Augustinavicius, J., & Scott, J. G. (2021). Climate change and mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4486. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094486

- Chierzi, F., Toniolo, I., Allegri, F., Storbini, V., Belvederi, M. M., Triolo, F., … Tarricone, I. (2014). Psychiatric consequences of disasters in Italy: A systematic review. Minerva Psichiatrica, 55(2), 91–103.

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

- de’Donato, F. K., Stafoggia, M., Rognoni, M., Poncino, S., Caranci, N., Bisanti, L., … Perucci, C. A. (2008). Airport and city-centre temperatures in the evaluation of the association between heat and mortality. International Journal of Biometeorology, 52(4), 301–310. doi:10.1007/s00484-007-0124-5

- Di Fiorino, M., Massimetti, G., Corretti, G., & Paoli, R. A. (2005). Post-traumatic stress psychopathology 8 years after a flooding in Italy. Bridging Eastern and Western Psychiatry, III(1), 49–57.

- Di Fiorino, M., Massimetti, G., Nencioni, M., & Paoli, R. A. (2004). Forma piena e sottosoglia del disturbo post-traumatic da stress nelle squadre di soccorso sette anni dopo un’alluvione. Psichiatria e Territorio, XXI(1), 32–40.

- Di Giorgi, E., Michielin, P., & Michielin, D. (2020). Perception of climate change, loss of social capital and mental health in two groups of migrants from African countries. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore Di Sanità, 56(2), 150–156.

- Di Nicola, M., Mazza, M., Panaccione, I., Moccia, L., Giuseppin, G., Marano, G., … Janiri, L. (2020). Sensitivity to climate and weather changes in euthymic bipolar subjects: Association with suicide attempts. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 95. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00095

- EFFIS. (2021). EFFIS-Estimates per country. https://effis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/apps/effis.statistics.portal/effis-estimates/EU.

- Florido Ngu, F., Kelman, I., Chambers, J., & Ayeb-Karlsson, S. (2021). Correlating heatwaves and relative humidity with suicide (fatal intentional self-harm). Scientific Reports, 11(1), 22175. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01448-3

- Fontalba-Navas, A., Lucas-Borja, M. E., Gil-Aguilar, V., Arrebola, J. P., Pena-Andreu, J. M., & Perez, J. (2017). Incidence and risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in a population affected by a severe flood. Public Health, 144, 96–102. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.12.015

- French, C. E., Waite, T. D., Armstrong, B., Rubin, G. J., Group, E. N. S. o. F. a. H. S., Beck, C. R., & Oliver, I. (2019). Impact of repeat flooding on mental health and health-related quality of life: A cross-sectional analysis of the English national study of flooding and health. BMJ Open, 9(11), e031562. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031562

- Giacomini, G., Aguglia, A., Amerio, A., Escelsior, A., Capello, M., Cutroneo, L., … Amore, M. (2022). The need for collective awareness of attempted suicide rates in a warming climate. Crisis, 43(2), 157–160. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000763

- Haddaway, N. R., Page, M. J., Pritchard, C. C., & McGuinness, L. A. (2022). PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18, e1230 doi:10.1002/cl2.1230

- Helama, S., Holopainen, J., & Partonen, T. (2013). Temperature-associated suicide mortality: Contrasting roles of climatic warming and the suicide prevention program in Finland. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 18(5), 349–355. doi:10.1007/s12199-013-0329-7

- Kendrovski, V., Baccini, M., Sanchez Martinez, G., Wolf, T., Paunovic, E., & Menne, B. (2017). Quantifying projected heat mortality impacts under 21st-century warming conditions for selected European countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 729. doi:10.3390/ijerph14070729

- Kim, Y., Kim, H., Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B., Honda, Y., Chung, Y., Ng, C., Tobias, A., Íñiguez, C., Lavigne, E., Sera, F., Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Ragettli, M. S., Scovronick, N., Acquaotta, F., Chen, B. Y., Guo, Y. L., Seposo, X., Dang, T. N., de Sousa Zanotti Stagliorio Coelho, M., … Hashizume, M. (2019). Suicide and ambient temperature: A multi-country multi-city study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127(11), 117007. doi:10.1289/EHP4898

- Lawrance, E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G., & Jennings, N. (2021). The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: Current Evidence and Implications for Policy and Practice. https://www.imperial.ac.uk/grantham/publications/all-publications/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-mental-health-and-emotional-wellbeing-current-evidence-and-implications-for-policy-and-practice.php.

- Liu, J., Varghese, B. M., Hansen, A., Xiang, J., Zhang, Y., Dear, K., … Bi, P. (2021). Is there an association between hot weather and poor mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International, 153, 106533. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2021.106533

- Martinaki, S., Kostaras, P., Mihajlovic, N., Papaioannou, A., Asimopoulos, C., Masdrakis, V., & Angelopoulos, E. (2021). Psychiatric admission as a risk factor for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research, 305, 114176. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114176

- Massazza, A., Teyton, A., Charlson, F., Benmarhnia, T., & Augustinavicius, J. (n.d.). Quantitative methods for climate change and mental health research: Current trends and future directions [Paper submitted for publication]

- Miceli, R., Sotgiu, I., & Molinengo, G. (2010). Preoccupazione, probabilità di accadimento e comportamenti preventivi rispetto al rischio alluvionale in una zona di montagna. Ricerche di Psicologia, doi:10.3280/RIP2010-001007

- Michelozzi, P., Donato, F. d., Bisanti, L., Russo, A., Cadum, E., DeMaria, M., … Perucci, C. A. (2005). The impact of the summer 2003 heat waves on mortality in four Italian cities. Eurosurveillance, 10(7), 11–12. doi:10.2807/esm.10.07.00556-en

- Ministero della Salute. (2019). Piano nazionale di prevenzione degli effetti del caldo sulla salute. https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2867_allegato.pdf.

- Mitchell, A. M., & Terhorst, L. (2017). PTSD symptoms in survivors bereaved by the suicide of a significant other. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 23(1), 61–65. doi:10.1177/1078390316673716

- Müller, H., Biermann, T., Renk, S., Reulbach, U., Ströbel, A., Kornhuber, J., & Sperling, W. (2011). Higher Environmental temperature and global radiation are correlated with increasing suicidality—A localized data analysis. Chronobiology International, 28(10), 949–957. doi:10.3109/07420528.2011.618418

- National Institute of Health. (2021). Study quality assessment tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 467–480. doi:10.1017/S0033291707001353

- Oudin Åström, D., Schifano, P., Asta, F., Lallo, A., Michelozzi, P., Rocklöv, J., & Forsberg, B. (2015). The effect of heat waves on mortality in susceptible groups: A cohort study of a Mediterranean and a northern European city. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 14, 30. doi:10.1186/s12940-015-0012-0

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Page, L. A., Hajat, S., & Kovats, R. S. (2007). Relationship between daily suicide counts and temperature in England and Wales. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(2), 106–112. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.031948

- Page, L. A., Hajat, S., Kovats, R. S., & Howard, L. M. (2012). Temperature-related deaths in people with psychosis, dementia and substance misuse. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 200(6), 485–490. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.100404

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Mcinerney, P., Munn, Z., Trico, A., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. doi:10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

- Petralli, M., Morabito, M., Cecchi, L., Crisci, A., & Orlandini, S. (2012). Urban morbidity in summer: Ambulance dispatch data, periodicity and weather. Open Medicine, 7(6), 775–782. doi:10.2478/s11536-012-0056-2

- Pianigiani, G. (2021). Sicily registers record-high temperature as heat wave sweeps Italian island. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/12/world/europe/sicily-record-high-temperature-119-degrees.html.

- Preti, A. (1997). The influence of seasonal change on suicidal behaviour in Italy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 44(2–3), 123–130. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00035-9

- Preti, A., Lentini, G., & Maugeri, M. (2007). Global warming possibly linked to an enhanced risk of suicide: Data from Italy, 1974-2003. Journal of Affective Disorders, 102(1–3), 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.003

- Preti, A., & Miotto, P. (1998). Seasonality in suicides: The influence of suicide method, gender and age on suicide distribution in Italy. Psychiatry Research, 81(2), 219–231. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00099-7

- Preti, A., & Miotto, P. (2000). Influence of method on seasonal distribution of attempted suicides in Italy. Neuropsychobiology, 41(2), 62–72. doi:10.1159/000026635

- Robine, J.-M., Cheung, S. L. K., Le Roy, S., Van Oyen, H., Griffiths, C., Michel, J.-P., & Herrmann, F. R. (2008). Death toll exceeded 70,000 in Europe during the summer of 2003. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 331(2), 171–178. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.12.001

- Rocklöv, J., Forsberg, B., Ebi, K., & Bellander, T. (2014). Susceptibility to mortality related to temperature and heat and cold wave duration in the population of Stockholm county, Sweden. Global Health Action, 7. doi:10.3402/gha.v7.22737

- Romanello, M., Daalen, K. v., Anto, J. M., Dasandi, N., Drummond, P., Hamilton, I. G., … Nilsson, M. (2021a). Tracking progress on health and climate change in Europe. The Lancet Public Health, 6(11), e858–e865. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00207-3

- Romanello, M., McGushin, A., Napoli, C. D., Drummond, P., Hughes, N., Jamart, L., … Hamilton, I. (2021b). The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Code red for a healthy future. The Lancet, 398(10311), 1619–1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6

- Rotgé, J.-Y., Fossati, P., & Lemogne, C. (2014). Climate and prevalence of mood disorders: A cross-national correlation study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(4), 408. doi:10.4088/JCP.13l08810

- Schifano, P., Cappai, G., De Sario, M., Michelozzi, P., Marino, C., Bargagli, A. M., & Perucci, C. A. (2009). Susceptibility to heat wave-related mortality: A follow-up study of a cohort of elderly in Rome. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 8, 50. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-50

- Settineri, S., Mucciardi, M., Leonardi, V., Schlesinger, S., Gioffrè Florio, M., Famà, F., … Mento, C. (2016). Metereological conditions and psychiatric emergency visits in messina, Italy. International Journal of Psychological Research, 9(1), 72–82. doi:10.21500/20112084.2103

- Stafoggia, M., Forastiere, F., Agostini, D., Biggeri, A., Bisanti, L., Cadum, E., … Perucci, C. A. (2006). Vulnerability to heat-related mortality: A multicity, population-based, case-crossover analysis. Epidemiology (Cambridge, MA), 17(3), 315–323. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000208477.36665.34

- Stafoggia, M., Forastiere, F., Agostini, D., Caranci, N., de’Donato, F., Demaria, M., … Perucci, C. A. (2008). Factors affecting in-hospital heat-related mortality: A multi-city case-crossover analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(3), 209–215. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.060715

- Stivanello, E., Chierzi, F., Marzaroli, P., Zanella, S., Miglio, R., Biavati, P., … Pandolfi, P. (2020). Mental health disorders and summer temperature-related mortality: A case crossover study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), E9122. doi:10.3390/ijerph17239122

- Stratta, P., Rossetti, M. C., di Michele, V., & Rossi, A. (2016). [Effects on health of the L’Aquila (central Italy) 2009 earthquake]. Epidemiologia E Prevenzione, 40(2 Suppl 1), 22–31. doi:10.19191/EP16.2S1.P022.044

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

- UNEP. (2020). Climate change in the Mediterranean. https://www.unep.org/unepmap/resources/factsheets/climate-change.

- Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Scovronick, N., Sera, F., Royé, D., Schneider, R., Tobias, A., … Gasparrini, A. (2021). The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nature Climate Change, 11(6), 492–500. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x

- World Health Organization. (2018). Climate and health country profile: Italy. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260380/WHO-FWC-PHE-EPE-15.52-eng.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y.

Appendices

Appendix A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist

Appendix B: Complete MEDLINE search strategy used.

Appendix C: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix D: Papers excluded following full-text assessment (with reason).

Appendix E: Descriptive information on studies included in scoping review.

Appendix F: Details on quality assessment (conducted using NIH Study Quality Assessment Tools: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools).