ABSTRACT

Background

As provisions of mental healthcare services to military and veteran populations increases the risk to service providers developing secondary traumatic stress (STS), efforts are needed to examine the impact of delivering novel interventions which may include 3MDR. As a virtual-reality supported intervention, 3MDR exposes the patient, therapist and operator to graphic and sensory stimuli (i.e. narratives, imagery, smells, and music) in the course of the intervention. 3MDR is actively being researched at multiple sites internationally within military and veteran populations. It is, therefore, crucial to ensure the safety and wellbeing of 3MDR therapists and operators who are exposed to potentially distressing sensory stimuli.

Objective

The purpose of this study is to qualitatively examine the impact and experiences of STS amongst therapists and operators in delivering 3MDR. For this study, impact will be defined as therapists or operators experiencing perceived STS as a result of delivering 3MDR.

Methods

This exploratory qualitative study recruited 3MDR therapists and operators (N = 18) from Canada, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States who had previously delivered 3MDR therapy. Telephone or video-conferencing interviews were used to gather data that was subsequently transcribed and thematically analyzed.

Results

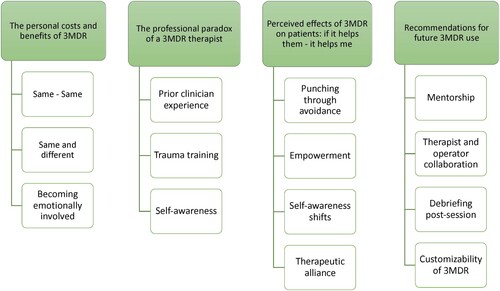

Four themes emerged among the therapists (n = 13) and operators (n = 5): (1) personal cost and benefits of 3MDR, (2) professional paradox of a 3MDR therapist, (3) perceived effect of 3MDR on patients, and (4) recommendations for future 3MDR use.

Conclusions

STS was not noted to be a significant challenge for 3MDR therapists and operators. Future research may investigate optimal means of providing training and ongoing support for 3MDR therapists and operators.

HIGHLIGHTS

Secondary Traumatic Stress was not noted to be a significant challenge for 3MDR therapists and operators

Future research may investigate optimal means of providing training and ongoing support for 3MDR therapists and operators

Antecedentes: Dado que la prestación de servicios de atención en salud mental a poblaciones de militares y veteranas aumenta el riesgo de que los proveedores de la atención desarrollen estrés traumático secundario (STS en sus siglas en inglés), se requieren esfuerzos para examinar el impacto de la entrega de intervenciones novedosas que pueden incluir 3MDR. Una intervención de apoyo de realidad virtual, 3MDR expone al paciente, terapeuta y operador a estímulos sensoriales y gráficos (es decir, narrativas, imágenes, olores y música) en el transcurso de la intervención.3MD está siendo investigada activamente en múltiples sitios a nivel internacional dentro de poblaciones militares y de veteranos. Por lo tanto, es crucial garantizar la seguridad y bienestar de los terapeutas y operadores de 3MDR que están expuestos a estímulos sensoriales potencialmente perturbadores.

Objetivo: El propósito de este estudio es examinar cualitativamente el impacto y las experiencias de STS entre terapeutas y operadores que entregan 3MDR. Para este estudio, el impacto se definirá como los terapeutas o los operadores experimentan los STS percibidos como resultado de la entrega de 3MDR.

Método: Este estudio cualitativo exploratorio reclutó a terapeutas y operadores 3MDR (N = 18) de Canadá, Holanda, Reino Unido y Estados Unidos de Norteamérica, quienes previamente habían dado terapia 3MDR. Se usaron entrevistas telefónicas o por videoconferencias para reunir los datos que luego se transcribieron y analizaron temáticamente.

Resultados: Emergieron 4 temas entre los terapeutas (N = 13) y operadores (N = 5): (1) costo personal y beneficios de 3MDR, (2) paradoja profesional de un terapeuta 3MDR, (3) efecto percibido de 3MDR en los pacientes, y (4) recomendaciones para el uso futuro de 3MDR.

Conclusiones: No se notó que STS fuera un desafío significativo para los terapeutas y operadores de 3MDR. Investigaciones futuras pueden investigar medios óptimos para proporcionar formación y apoyo continuo para los terapeutas y operadores 3MDR.

Destacados: No se observó que el Estrés Traumático Secundario fuera un desafío significativo para los terapeutas y operadores 3MDR. Investigaciones futuras pueden investigar medios óptimos para proporcionar formación y apoyo continuo para los terapeutas y operadores 3MDR.

背景: 由于向军人和退伍军人提供心理保健服务会增加服务提供者发生二次创伤应激 (STS) 的风险,因此需要努力考查提供可能包括 3MDR 在内的新型干预措施的影响。 3MDR 是一种虚拟现实辅助干预,在干预过程中让患者、治疗师和操作员接触到图形和感官刺激(即叙事、图像、气味和音乐)。 3MDR 正在国际各地积极的军人和退伍军人中被研究。因此,确保暴露于潜在痛苦感官刺激的 3MDR 治疗师和操作员的安全和福祉至关重要。

目的: 本研究旨在定性考查 STS 治疗师和操作者在提供 3MDR 方面的影响和体验。在本研究中,影响将定义为治疗师或操作者因提供 3MDR 而体验到感知 STS。

方法: 本探索性定性研究从加拿大、荷兰、英国和美国招募之前曾进行过 3MDR 治疗 的3MDR 治疗师和操作者(N = 18)。使用电话或视频会议访谈收集随后被转录和主题分析的数据。

结果: 治疗师 (n = 13) 和操作员 (n = 5) 中出现了四个主题:(1) 3MDR 的个人成本和收益,(2) 3MDR 治疗师的专业悖论,(3) 3MDR 对患者的感知效果,以及 (4) 对未来 3MDR 使用的建议。

结论: 没有发现STS 对 3MDR 治疗师和操作者构成显著挑战。未来的研究可能会调查为 3MDR 治疗师和操作员提供培训和持续支持的最佳方式。

亮点: 没有发现二次创伤应激对 3MDR 治疗师和操作者构成显著挑战。未来的研究可能会调查为 3MDR 治疗师和操作员提供培训和持续支持的最佳方式。

1. Background

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition caused by experiencing or witnessing an event, or cumulative events, where there is a real or perceived threat to self or others (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013). Characterized by enduring symptoms related to negative cognitive intrusions, avoidance, hypervigilance, and alterations in mood, arousal, and reactivity, PTSD is the most common mental illness experienced by military members and veterans globally (APA, Citation2013; Levy & Sidel, Citation2009). Multiple first-line evidence-based treatments have been developed to facilitate treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery of military members and veterans living with PTSD. Common first-line treatment modalities include trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR; Forbes et al., Citation2019; Hamblen et al., Citation2019; Rehman et al., Citation2019). While providing mental healthcare to this population can be both incredibly rewarding and challenging, the vicarious exposure to traumatic content, often combined with a demanding workload, can leave some healthcare professionals (HCPs) at risk of experiencing secondary traumatic stress (STS; Kintzle, Yarvis, & Bride, Citation2013).

1.1. Secondary traumatic stress

The indirect transmission of trauma and PTSD symptomology from a traumatized individual to another is a process known as secondary traumatic stress (STS). Secondary trauma is described ‘as a natural consequence of wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person’ (Figley, Citation1995, p. 7). This term is often used interchangeably with vicarious trauma (VT), and similarly occurs after repeated exposure and empathetic engagements, resulting in a negative cognitive and/or worldview shift (Cieslak et al., Citation2013; Jordan, Citation2010).

STS may be particularly pertinent to persons delivering psychotherapeutic interventions. Transferential dynamics (Darroch & Dempsey, Citation2016) inherent in the traditional talk therapy relationship can create psychological risk and affective distress for therapists. Given the relational nature of healing, greater indirect exposure to a client’s trauma is associated with higher risk of STS development (Lee, Gottfried, & Bride, Citation2018; Penix et al., Citation2020), with potentially harmful psychological sequelae (Prichard, Citation1998). Personal trauma history, workload, and external stressors are known to correlate with STS (Sodeke-Gregson, Holttum, & Billings, Citation2013), and elevated STS levels are associated with lower health perceptions and self-awareness in clinicians (Lee et al., Citation2018).

Healthcare professionals experiencing STS do not always meet the established cut-offs for clinically significant levels that would warrant further diagnosis of a psychological disorder (Penix, Kim, Wilk, & Adler, Citation2019). The DSM5 recognizes secondary exposure to trauma in Criterion A for PTSD, which applies to workers who encounter the consequences of traumatic events within their professional role (APA, Citation2013). Research has provided some insight into how different factors and contexts affect or correlate with STS in specific types of healthcare professionals.

Military therapists have been found to be both among those with the highest (Cieslak et al., Citation2013) and lowest (Kintzle et al., Citation2013) STS levels in comparison to civilian therapists (Ballenger-Browning et al., Citation2011). Specific components of psychotherapy for military trauma have been explored in an attempt to explain these paradoxical results. Devilly, Wright, and Varker (Citation2009) compared trauma exposure through delivering PE and/or CPT and found that these modalities were not predictive of STS. Researchers have hypothesized that therapists with a high degree of specialty training (i.e. in PE or CPT) may experience higher degrees of professional efficacy protective against STS (Finley et al., Citation2015; Garcia et al., Citation2016). This argument has been supported by more recent research which has shown that therapists resistant to trying, or diverging from, evidence-based practices can be associated with increased STS risk (Garcia et al., Citation2016; Penix et al., Citation2020). Finally, while hearing traumatic details of military service may increase STS risk, military cultural competence has been found to potentially protect civilians working with military trauma (Linnerooth, Mrdjenovich, & Moore, Citation2011).

Unmediated STS has the potential to negatively impact the personal and professional lives of therapists. STS may lead to psychological detachment and cynicism coupled with decreasing job efficacy and ethical decision making (Denne, Stevenson, & Petty, Citation2019). Those impacted by STS report experiencing self-doubt, exhaustion, physical health challenges (Foreman & Savitsky, Citation2020), reduce perceptions of health (Lee et al., Citation2018), emotional detachment (Prichard, Citation1998), shame, and/or stigma (Johnson et al., Citation2011). Further, findings indicate that STS has the potential to impair military psychologists’/soldiers’ ability to identify and address ethical issues during deployment and post-deployment (Johnson et al., Citation2011). This could result in therapists being unable to provide the best possible therapeutic services to their clients which has wide-reaching consequences for civilians and military personnel and organizations (Garcia, McGeary, McGeary, Finley, & Peterson Citation2014). STS-impacted professional competency can have detrimental ramifications on treatment efficacy, institutional productivity and staffing related to therapist retention and absenteeism (Garcia et al., Citation2014). With each novel clinical intervention developed for trauma-affected populations, there exists the need for monitoring and evaluation of the effects on, not only the patient, but among the treating therapists who could be vulnerable to STS. Importantly, not all therapists exposed to secondary trauma develop STS; as complex interrelated factors support or thwart individual homeostasis (Selye, Citation1974).

1.2. 3MDR intervention

Multi-modular Motion-assisted Memory Desensitization and Reconsolidation (3MDR) is a novel PTSD intervention that combines principles of virtual reality exposure therapy and EMDR in the context of walking on a treadmill while interacting with self-selected images and music (Bisson et al., Citation2020; van Gelderen, Nijdam, Haagen, & Vermetten, Citation2020; Jones et al., Citation2020). The 3MDR intervention is delivered using one of three virtual reality systems: the Computer Assisted Rehabilitation ENvironment (CAREN), the CAREN Light, or the Gait Real-time Analysis Interactive Lab (GRAIL), each of which facilitates full immersion and engagement. A treadmill (located in the center of a room) is surrounded by 240 degree floor-to-ceiling screens. In each session, the client continually walks on the treadmill while listening to self-selected music prior to viewing a series of seven (3–5 minutes each) self-selected images reminiscent of their trauma (van Gelderen, Nijdam, & Vermetten, Citation2018).

During the 3MDR sessions, an operator of the CAREN or GRAIL is present to run the software and manage the system, while a therapist delivers the 3MDR intervention and supportive counsel to the client. Throughout the intervention, the therapists and operators are exposed to potentially injurious graphic narratives, imagery and stimuli. Little is known about the cumulative effects of delivering multi-modal trauma exposure as prior research in STS has primarily focused on the secondary effects of psychotherapy. The shared traumatic reality of therapists and operators to the VR of graphic imagery and narratives may contribute to STS. Even less is known about the experience of the 3MDR operator’s experience during the 3MDR intervention. There is a need to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the staff associated with novel interventions incorporating realistic exposure to potentially traumatic sensory stimuli.

1.2.1. Purpose

The purpose of this study is to qualitatively examine the impact and experiences of STS amongst therapists and operators in delivering 3MDR. For this study, impact will be defined as therapists or operators perceiving an experience of STS as a result of their participation in 3MDR therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study utilized an exploratory qualitative design with thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017).

2.2. Recruitment and sampling

In light of the exploratory nature of the study, desire to determine the lived experiences of all personnel involved in 3MDR and the limited number of potential participants globally, it was decided to interview both operators and clinicians. Recruitment was initiated via email circulated to 3MDR therapists and operators by key stakeholders associated with the 3MDR studies at 7 sites within Canada, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States. 3MDR therapists and operators who were interested in participating in the study were instructed to email the research team to indicate consent to be contacted. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were forwarded an online consent form via a secure server (RedCap) and an interview time was scheduled. Potential participants were informed that engagement in the study was voluntary. This study received University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00084466) and the Canadian Armed Forces Surgeon General approval (E2019-02-250-003-0003).

2.3. Inclusion criteria

Participants included in this study were English-speaking current or previous 3MDR therapists or operators who were trained by the developer of 3MDR. Participants must have completed a full course of 3MDR delivery with at least one patient (i.e. had completed 6 sessions utilizing the CAREN/GRAIL in the VR environment). The target sample size was based on the number of 3MDR operators and therapists there are globally which was estimated to be less than 30. Due to the low number of potential participants existing worldwide, convenience and snowball sampling was utilized. A total of 18 participants (n = 13 therapist and n = 5 operators) agreed to participate, met the eligibility criteria, consented via RedCap and were interviewed. Although not all 3MDR operators and therapists in the world agreed to participate, data saturation (i.e. when no new data was emerging) was still reached at approximately participants 12-13.

2.4. Data collection

A demographic questionnaire was provided via email to participants through the RedCap server. Variables collected included the participant’s sex, profession, role in delivering 3MDR, years utilizing 3MDR, location, VR system used, and level of education. A semi-structured interview guide was developed to assist the research team with the deductive qualitative interview questions while leaving space for the inductive nature of the thematic analysis (Supplementary Materials – Appendix 1). These interview questions deductively addressed themes regarding STS, the experience of the therapists and operators working with military and veteran populations, their experience working with trauma-affected populations, and what they thought about the 3MDR intervention. There were no major, relevant, or noteworthy changes to the number or kinds of questions being asked in the interview. Rather the changes to the interview guide focused on modifying the questions to allow for deeper and richer data to be collected based on preliminary themes that naturally arose from the interviews (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Creswell, Citation1997). The research team conducted individual 40-to-60-minute interviews via telephone or a secure Zoom platform. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed by the research team. To ensure the accuracy of the transcripts one junior member of the research team was assigned to do the initial transcription before a second member was assigned to review the transcript.

2.5. Data analysis

Qualitative interview data were subjected to thematic analysis to identify, analyze and report patterns (themes) in rich detail, and allow the researcher to interpret various aspects of the topic (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Thematic analysis also allowed for both inductive and deductive approaches, both of which were used by the research team. The deductive analysis was guided by the research questions regarding the effect of 3MDR on the therapists and operators, and the perceived strengths (e.g, what makes 3MDR better than other trauma modalities), weaknesses (e.g. what effect did offering 3MDR have on you), and recommendations (e.g. in what way could the 3MDR be improved) associated with the delivery of 3MDR. To facilitate deductive coding, four junior researchers developed open codes based on in vivo language that were specifically related or derived from the semi-structured interview questions. The open codes were generated specifically from in vivo language to allow the researchers to stay faithful and close to the data and not impart their own biases at this stage of the coding process. All coding was done independently (i.e. each transcript was assigned to one member of the research team who conducted the coding) before having a second researcher re-code the interview. This allowed for interreliablity between the interviews as all of the interviews were coded at least twice. The results of these initial open coding processes resulted in 25 codes which were broken down into the three areas of interest: strengths, weakness, and recommendations. Once completed, the whole research team met to compare and contrast the deductive open codes across the different interviews. Differences of opinion between members of the research team regarding codes were resolved through discussion. Limited discussions were required as the deductive codes were able to be easily constructed and there was a continuity between the interpretations of the researchers across the different interviews and the data itself.

The exact same process was used for the inductive coding process. Once the deductive coding was completed, the four junior researchers were assigned new (i.e. different from the interviews they had deductively coded) interviews to inductively code. In this instance, specific attention was given to data that fell outside the semi-structured questions or regarding the research question concerning the impact of offering 3MDR on operators and therapists. The initial open inductive coding process yielded an initial 20 additional codes, which were further refined during the secondary level of coding. Once the inductive themes were established these were compared and integrated into the deductive analysis. In particular, this resulted in inductive codes where appropriate being placed beside the deductive codes, and where not appropriate to leave those codes as independent (i.e. did not overlap with the deductive). The 45 open codes were collapsed into 4 primary themes and 14 sub themes according to the observed patterning.

Following review of the data and completion of the secondary level of analysis, the themes were narratively summarized with the aim of organizing, describing, exploring, and interpreting the analysis. Key quotes were selected to substantiate the findings and were based on the open codes. To ensure the validity, reliability (dependability), and conformability of the analysis, researcher bias was clarified and bracketed. To assist with the bracketing of the teams’ bias, the four junior analysts were chosen as they did not have experience with 3MDR as a treatment modality. Moreover, they were instructed to not rely on a-priori experiences nor review literature related to secondary or vicarious trauma. Instead, when coding deductively they were to focus on the research questions and when coding inductively to simply follow whatever arose from the data. The integration of the inductive component of the analysis supported the team to bracket their biases as pertinent data was captured which was outside of the set research questions. Finally, the researchers were also instructed not to share their coding with each other until all interviews had been coded at least twice to try and avoid conformity in interpretations. An internal audit (i.e. a review of the above steps) of the analysis was made by two senior members of the research team (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Morse, Citation2015).

3. Results

Demographic details of the study sample (N = 18) are summarized in . Study participants had diverse professional backgrounds, education and experience levels, were equally males and females, and resided in 4 separate countries (). These demographic results are relevant to the qualitative results below because despite the diversity found (i.e, age, education, previous experience) there were very clear themes that emerged regarding the experience of 3MDR operators and therapists.

Table 1. Sample demographics.

Table 2. Education and experience of sample.

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data constructed four main themes that related to how 3MDR as a therapeutic modality influences therapist personal and professional experiences: (1) personal cost and benefits of 3MDR (2) professional paradox of a 3MDR therapist, (3) perceived effect of 3MDR on patients, and (4) recommendations for future 3MDR use. What follows is an elaboration of these themes, together with tables of sub-themes and supporting quotes ().

3.1. Theme 1: the personal costs and benefits of 3MDR

Participants recognized that exposure to traumatic stimuli is inherent in therapeutic work with military members and veterans. While a primary interest of this study was STS, this was not found in the data. While participants acknowledged that traumatic stimuli may be harder to avoid because of the intensive and virtual components of the 3MDR (subtheme ‘same and different), they did not report differences between performing 3MDR and other trauma modalities (). Instead, participants spoke to the overall struggles of not being affected when doing any form of trauma work; particularly as this ability to be emotive is often the foundation of the therapeutic alliance and the ability of the clinician to offer compassionate non-judgmental positive regard (subtheme ‘same-same’). Hearing the stories from 3MDR patients offered some participants greater insight into and understanding of the patient’s experience with trauma, and a deeper appreciation of the struggles endured by their clients (subtheme ‘becoming emotionally involved’). Participants reported that this experience had a positive impact on their own clinical practice.

Table 3. The personal costs and benefits of 3MDR.

3.2. Theme 2: the professional paradox of a 3MDR therapist

Characteristics of a 3MDR therapist were explored by participants. Some found it very helpful to have an educational background in psychology, counseling, social sciences or nursing in order to prepare them for the 3MDR (subtheme ‘prior clinician experience’) (). Equally participants’ responses were mixed as to whether 3MDR is suitable for therapists lacking military experience, with some noting that a military background was beneficial to relating to 3MDR clients. While this was not deemed essential, participants acknowledged that previous experience providing trauma therapy could be an asset given the intensity of the content being processed and the severity of symptoms being presented by the 3MDR clients (subtheme ‘trauma training’) As such, the participants felt 3MDR may not be a suitable modality for newer therapists. More experienced clinicians, however, mentioned they struggled at times to effectively follow 3MDR protocols, depending on the trauma modalities that they had been previously trained in. All participants agreed on the need for 3MDR clinicians and operators to be self-aware of personal triggers, symptoms of distress, or issues of transference and countertransference so as to ensure resiliency and self-care (subtheme ‘self-awareness’).

Table 4. The professional paradox of a 3MDR therapist.

3.3. Theme 3: perceived effects of 3MDR on patients: if it helps them – it helps me

Interestingly, all participants noted that it was seeing their clients improve that was a protective factor to 3MDR not being harmful to their mental health. For example, despite the noted intensity of 3MDR, therapists found that patients who were more avoidant were better able to address their trauma by being in 3MDR’s multi-sensory, immersive environment and ‘walking toward their trauma’ resulting in better therapeutic outcomes (subtheme ‘punching through avoidance’) (). They also felt that their clients were more empowered in 3MDR than in other trauma modalities given the self-directedness of the modality which again supported not only symptom reduction but also encouraged self-esteem, confidence and pride in their clients (subtheme ‘empowerment’). For the therapist, this change in participants was also empowering, resulting in a desire to continue with 3MDR despite the intense psychological stimulations associated with doing this type of trauma therapy. Similarly, participants believed that their clients had increased self-awareness and were gaining a deeper understanding of their trauma while they were facing their fears which also supported the therapist to have confidence that the trauma work was effective (subtheme ‘self-awareness shifts’). Finally, therapists enjoyed how 3MDR facilitated rapport-building and strengthened the intimacy of the therapeutic alliance between therapist and client in a way that is specifically unique to 3MDR (subtheme ‘therapeutic alliance’).

Table 5. Perceived effects of 3MDR on patients.

3.4. Theme 4: recommendations for future 3MDR use

Participants provided recommendations for the future use of 3MDR as a therapeutic modality, and expressed the need for greater mentorship and improvements in technology (). In particular, it was suggested that enhanced mentorship could include: (1) more hands-on-experience; (2) having a co-treatment session with another more experienced 3MDR therapist; and (3) the opportunity to practice with various traumatic images (subtheme ‘mentorship’). Therapists emphasized the importance of preparing oneself (especially the operator) for a treatment session and the need for collaboration between operator and therapist to effectively manage the sessions (subtheme ‘therapist-operator collaboration’). Participants noted this relationship between the therapist and operator was often overlooked in training but was essential to being able to do 3MDR. Another recommendation was to have a debrief post session to explore if self-care for the therapist or operator was needed (subtheme ‘debriefing post session’). Finally, therapists and operators were excited about the future of 3MDR which they hoped would have opportunities for specific customizability and tailoring of the intervention in the clinical environment (subtheme ‘customizability of 3MDR’).

Table 6. Recommendation for future 3MDR use.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the experiences of therapists and operators in delivering 3MDR, and specifically address if therapists or operators experience perceived STS as a result of their participation delivering 3MDR. While providing 3MDR intervention may have a profound effect on therapists and operators, STS was not reported as a prominent concern in this study. Therapists and operators were moved by the narratives of their patients and the overall experience of providing 3MDR, yet any perceived distress did not last longer than a day. The therapists and operators at all sites felt that they had adequate support to process in-session situations, and knew how to obtain additional mental health support, if required. The 3MDR therapists and operators were eager to share their experiences delivering 3MDR to military and veteran personnel with PTSD. Despite the deductive nature of the semi-structured interview focusing on the potential for STS, participants were passionate and pensive regarding how best to assist military and veteran personnel in their trauma recovery and healing through 3MDR. A multitude of hypotheses were presented: the nature surrounding 3MDR efficacy, the characteristics, education, and experiences a 3MDR therapist should possess, and what additional support, training, technology, and policies would improve 3MDR for both trauma-affected populations and the staff administering the intervention.

Overall, participants found their involvement in 3MDR rewarding, reporting that they would willingly participate in future studies, or adapt their clinical practice to include this novel intervention. Even among therapists experiencing STS, trauma therapies remain fulfilling. Compassion satisfaction (defined as experiencing positive impacts in relation to traumatology work) and posttraumatic growth are positive outcomes related to trauma exposure and stress reactions (Coleman, Chouliara, & Currie, Citation2021). Some therapists report STS as a gateway to post-traumatic growth, embodied as relational interconnectedness with their biopsychosocial-spiritual, personal and professional selves, and within society (Foreman & Savitsky, Citation2020). Their subsequent engagement in advocacy highlights the importance of integrating personal morals into healthcare, and valuing therapists as experts so as to combat ‘an almost expected “cost of caring”’ (Epstein et al., Citation2020, p. 151).

4.1. Strengths and limitations of this study

This paper has a number of important strengths. First, it is the first paper to consider the potential impact of administering 3MDR on therapists and operators. As novel trauma interventions are created, attention is rarely given to the psychosocial wellbeing of healthcare professionals providing the intervention. Such an oversight is deeply problematic and can potentially limit the widespread adoption and implementation of the modality, particularly if therapists are inadvertently becoming injured or harmed during service provision. Second, this study sought to explore the impact of 3MDR on CAREN/GRAIL operators. As these operators are not mental health professionals, there was initial concern of increased risk of harm to their mental health and wellbeing. As operators are essential to the technological running of 3MDR, psychological injury during service provision could limit the ability to offer 3MDR as a standardized and readily available trauma treatment. Third, this study is strengthened by the collection of data from autonomous international sites and diverse 3MDR therapists and operators. By ensuring international representation, the risk of unintentional bias (i.e. variables of site management, training, and stigma) is limited. Fourth, the diversity of health professions represented within the sample ensures limited bias, possibly indicating the lack of harm can be attributed to 3MDR and not a specific training or proficiency.

There were also some important limitations of this study. First, despite achieving data saturation, the overall small sample size of the study may reduce the generalizability of the results to all 3MDR therapists and operators. Second, no quantitative data were collected on the constructs of interest (STS) which could objectively support the self-disclosure as reported by the participants. Lastly, participants were recruited via convenience snowball sampling, resulting in a self-selecting bias whereby those most eager to share their experience participated.

4.2. Recommendations and future directions

As research into 3MDR continues to expand, recommendations and future research could include the following:

The effect of 3MDR on staff, particularly as the 3MDR and its technological interfaces are further developed and used with other trauma-affected populations

The role of the therapeutic alliance in facilitating successful outcomes in 3MDR.

Therapist and operator characteristics and professional training which support the delivery of 3MDR by healthcare professionals.

Optimal means of providing training and ongoing support for 3MDR therapists and operators.

The perceived technology acceptance and usability of the hardware and software within therapists, operators, and trauma-affected populations.

The impact of perceived efficacy of the intervention for patients on therapist’s mental health.

Why 3MDR was more fatiguing to implement versus other evidence-based trauma interventions for therapists and operators

5. Conclusions

The treatment of PTSD continues to be an area of research and clinical practice of which novel and emerging interventions could hold the key to healing for trauma-affected populations, such as military personnel and veterans, that are known to have reduced success with first-line trauma treatments. Some emerging modalities, such as 3MDR, incorporate increasingly realistic sensory stimuli within their exposures which can have an effect on the patient, therapist or operator. Within this study, STS was not noted to be a significant challenge for 3MDR therapists and operators. Future research may investigate optimal means of providing training and ongoing support for 3MDR therapists and operators, as well as the perceived technology acceptance and usability of the hardware and software. Mixed-methods research that includes multiple stakeholders and leverages the experiences of the therapists and operators is ideal for ensuring that scientific, clinical, logistic, and holistic perspectives are considered when studying trauma treatments. A diverse and evidence-based approach to the development, implementation, and improvement of trauma treatments will best facilitate healing, recovery and post-traumatic growth for those who serve and have served humanity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25 KB)Acknowledgements

The research team would like to thank the global participants of this, and other, 3MDR studies for their work in progressing research into novel treatments for PTSD among military and veteran populations. The team would also like to thank the Nypels-Tans PTSD Fund in the Netherlands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on request only due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, CJ or SBP. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association. (2013). Trauma- and stressor-related disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm07

- Ballenger-Browning, K. K., Schmitz, K. J., Rothacker, J. A., Hammer, P. S., Webb-Murphy, J. A., & Johnson, D. C. (2011). Predictors of burnout among military mental health providers. Military Medicine, 176(3), 253–260. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00269

- Bisson, J. I., van Deursen, R., Hannigan, B., Kitchiner, N., Barawi, K., Jones, K., … Vermetten, E. (2020). Randomised controlled trial of multi-modular motion-assisted memory desensitisation and reconsolidation (3MDR) for male military veterans with treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142, 141–151. doi:10.1111/acps.13200

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cieslak, R., Anderson, V., Bock, J., Moore, B. A., Peterson, A. L., & Benight, C. C. (2013). Secondary traumatic stress among mental health providers working with the military: Prevalence and its work- and exposure-related correlates. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(11), 917–925. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000034

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Coleman, A. M., Chouliara, Z., & Currie, K. (2021). Working in the field of complex psychological trauma: A framework for personal and professional growth, training, and supervision. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5/6), 2791–2815. doi:10.1177/0886260518759062

- Creswell, J. (1997). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Darroch, E., & Dempsey, R. (2016). Interpreters’ experiences of transferential dynamics, vicarious traumatisation, and their need for support and supervision: A systematic literature review. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 4(2), 166–190. doi:10.5964/ejcop.v4i2.76

- Denne, E., Stevenson, M., & Petty, T. (2019). Understanding how social worker compassion fatigue and years of experience shape custodial decisions. Child Abuse and Neglect, 95, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104036

- Devilly, G. J., Wright, R., & Varker, T. (2009). Vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress or simply burnout? Effect of trauma therapy on mental health professionals. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(4), 373–385. doi:10.1080/00048670902721079

- Epstein, E. G., Haizlip, J., Liaschenko, J., Zhao, D., Bennett, R., & Marshall, M. F. (2020). Moral distress, mattering, and secondary traumatic stress in provider burnout: A call for moral community. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 31(2), 146–157. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2020285

- Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Washington, DC: Brunner/Mazel.

- Finley, E. P., Garcia, H. A., McGeary, D. D., McGeary, C. A., Peterson, A. L., Ketchum, N. S., & Stirman, S. W. (2015). Utilization of evidence-based psychotherapies in veterans affairs posttraumatic stress disorder outpatient clinics. Psychological Services, 12(1), 73–82. doi:10.1037/ser0000014

- Forbes, D., Pedlar, D., Adler, A. B., Bennett, C., Bryant, R., Busuttil, W., … Wessely, S. (2019). Treatment of military-related post-traumatic stress disorder: Challenges, innovations, and the way forward. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(1), 95–110. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1595545

- Foreman, T., & Savitsky, D. (2020). Describing the impact of our work as professional counselors shared voices. Wisconsin Counseling Journal, 33, 17–31.

- Garcia, H. A., McGeary, C. A., Finley, E. P., McGeary, D. D., Ketchum, N. S., & Peterson, A. L. (2016). The influence of trauma and patient characteristics on provider burnout in VA post-traumatic stress disorder specialty programmes. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(1), 66–81. doi:10.1111/papt.12057

- Garcia, H. A., McGeary, C. A., McGeary, D. D., Finley, E. P., & Peterson, A. L. (2014). Burnout in Veterans Health Administration mental health providers in posttraumatic stress clinics. Psychological Services, 11(1), 50.

- Hamblen, J. L., Norman, S. B., Sonis, J. H., Phelps, A. J., Bisson, J. I., Nunes, V. D., … Schnurr, P. P. (2019). A guide to guidelines for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: An update. Psychotherapy, 56(3), 359–373. doi:10.1037/pst0000231

- Johnson, W. B., Johnson, S. J., Sullivan, G. R., Bongar, B., Miller, L., & Sammons, M. T. (2011). Psychology in extremis: Preventing problems of professional competence in dangerous practice settings. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 94–104. doi:10.1037/a0022365

- Jones, C., Smith-MacDonald, L., Miguel-Cruz, A., Pike, A., van Gelderen, M., Lentz, L., … Brémault-Phillips, S. (2020). Virtual reality-based treatment for military members and veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Protocol for a multimodular motion-assisted memory desensitization and reconsolidation randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(10), e20620. doi:10.2196/20620

- Jordan, K. (2010). Vicarious trauma: Proposed factors that impact clinicians. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 21(4), 225–237. doi:10.1080/08975353.2010.529003

- Kintzle, S., Yarvis, J. S., & Bride, B. E. (2013). Secondary traumatic stress in military primary and mental health care providers. Military Medicine, 178(12), 1310–1315. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00087

- Lee, J. J., Gottfried, R., & Bride, B. E. (2018). Exposure to client trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and the health of clinical social workers: A mediation analysis. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46, 228–235. doi:10.1007/s10615-017-0638-1

- Levy, B. S., & Sidel, V. W. (2009). Health effects of combat: A life-course perspective. Annual Review of Public Health, 30, 123–136.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Linnerooth, P. J., Mrdjenovich, A. J., & Moore, B. A. (2011). Professional burnout in clinical military psychologists: Recommendations before, during, and after deployment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 87–93. doi:10.1037/a0022295

- Morse, J. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. doi:10.1177/1049732315588501

- Penix, E. A., Clarke-Walper, K. M., Trachtenberg, F. L., Magnavita, A. M., Simon, E., Ortigo, K., … Wilk, J. E. (2020). Risks of secondary traumatic stress in treating traumatized military populations: Results from the PTSD clinicians exchange. Military Medicine, 185(9/10), e1728–e1735. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa078

- Penix, E. A., Kim, P. Y., Wilk, J. E., & Adler, A. B. (2019). Secondary traumatic stress in deployed healthcare staff. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(1), 1–9. doi:10.1037/tra0000401

- Prichard, D. C. (1998). Compassion fatigue: When the helper needs help. Reflections Narratives of Professional Helping, 4(2), 13–20.

- Rehman, Y., Sadeghirad, B., Guyatt, G. H., McKinnon, M. C., McCabe, R. E., Lanius, R. A., … Busse, J. W. (2019). Management of post-traumatic stress disorder: A protocol for a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine, 98(39), e17064. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000017064

- Selye, H. (1974). The stress of life. In Stress without distress (pp. 25–29). Toronto: Mclelland & Steward.

- Sodeke-Gregson, E. A., Holttum, S., & Billings, J. (2013). Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in UK therapists who work with adult trauma clients. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(0), 1–10. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21869

- van Gelderen, M. J., Nijdam, M. J., Haagen, J. F. G., & Vermetten, E. (2020). Interactive motion-assisted exposure therapy for veterans with treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89, 215–227. https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/505977

- van Gelderen, M. J., Nijdam, M. J., & Vermetten, E. (2018). An innovative framework for delivering psychotherapy to patients with treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: Rationale for interactive motion-assisted therapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00176