ABSTRACT

Background: Food-borne diseases are contributing to health burdens globally, especially in developing countries. In India, milk production is important for nutrition security, but milk products are prone to contamination with pathogens. In Assam, a state in Northeast India, a novel hygiene intervention was conducted in 2009–2011, and the knowledge, attitudes and practices among milk producers, milk traders and sweet makers were assessed.Methods: The first survey was conducted in 2009 and included 405 producers, 175 traders and 220 sweet makers from 4 districts. The second survey was conducted in 2012 with 161 producers and 226 traders from 2 districts, both trained and untrained participants. In addition to questionnaires, observations on hygiene were done and samples were analysed for Escherichia coli.Results: In 2009 only 13.0%, 9.1%, and 33.1% of producers, traders and sweet makers respectively believed diseases could be transmitted by milk. There were significant improvements in knowledge after training among both traders and producers. The proportion of samples containing added water decreased from 2009 to 2012. Although knowledge had increased, all samples tested contained E. coli.Conclusion: This study shows a need to increase knowledge about milk-borne diseases and hygiene, and the positive effect of a training intervention.

Introduction

Food-borne pathogens are important causes of disease around the world [Citation1]. While increased use of effective technologies, good practices and awareness contributes to reduced incidence, poor quality water, longer and more complex value chains, reduced profit margins, and increased pollution can lead to increased problems with food and water-borne diseases [Citation2–Citation4]. The burden of food-borne diseases is unequally distributed, with around 98% of the burden in low and middle-income countries where it contributes to 4% of the total burden of disease [Citation1]. In poor countries, it is estimated that more than half a million children die every year of diarrhoea [Citation5]. Much of this can be attributed to food and especially animal-sourced food [Citation4,Citation6].

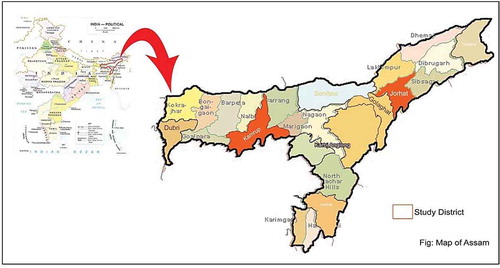

Figure 1. Map of India showing the location of the state of Assam, and the districts within the state.

Throughout the developing world, milk consumption has been increasing by 4 % annually, a trend likely to continue as the demand for animal-source food is increasing due to urbanization, increasing populations and increasing wealth [Citation7]. India has a population of more than one billion people, and since 2001 is the world’s leading milk producer. India also has the world’s largest cattle population at around 300 million, both buffalos and cows (Bos taurus and Bos indicus) [Citation8], and they annually produce 17% of the world’s total milk production [Citation9,Citation10]. In 2016-‘17 the total milk production was over 165.4 million tonnes [Citation9,Citation10]. The dairy sector is an important source of income for the 75% of the Indian population that lives in rural areas, of which 38% are poor; around 70 million Indian households are engaged in dairy production [Citation10]. Milk provides consumers a source of protein and calcium, which in a country with a large vegetarian population like India [Citation11], is of great importance; for many, dairy products are the sole source of animal proteins.

Although urbanisation is ongoing in India as in other countries, about 85% of the population (more than 30 million in 2011) in the Indian state Assam lives in rural areas and most (52%) are somehow dependent on agriculture [Citation12,Citation13]. Overall, 82% of households keep cattle, often in small herds of 2–8 animals [Citation14]. The dairy sector in the state is developing slower than in other parts of India and was only growing at a pace of 1.3% during 2002–03 to 2012–13 in contrast to the Indian average of 5.4%. The per capita availability of milk in Assam has also been low; only 70 g/day compared to the Indian average, 355 g/day, in 2016-‘17 [Citation9]. The informal market for dairy products dominates and only about 3% of milk goes through the formal pasteurized milk and dairy product market [Citation15]. In addition to the milk producers, dairy production is important for other value chain actors, including traders and the traditional sweet makers, who earn livelihood through milk trading or selling sweets. As the sector continues to develop and formalise, there has been increasing concerns about the safety and quality of the milk [Citation14].

Milk is nutritious for people, but it is also a nutritious substrate for bacteria, highly perishable and prone to contamination. A large number of bacteria and bacterial spores are present in the surroundings, on the cow’s skin, on the udder, and in certain conditions also in milk utensils and in persons handling milk, and these are easily transmitted to the milk at the point of milking or later handling [Citation16]. A previous study on milk samples from different parts of India [Citation17] found raw milk containing Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus. In addition to contaminants, mainly from the udder itself or from the handling of the milk, some disease agents, such as Brucella spp and mycobacteria, are transmitted through the milk and can cause serious disease in humans. These milk-borne zoonotic pathogens have also been reported in India [Citation18–Citation20].

Initial work in Assam indicated consumer concerns over food safety [Citation15]. Following from this, a survey was conducted in 2009 to assess the knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of dairy value chain actors in four districts. After this, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) initiated a training intervention in 2009 with the focus to improve hygiene and to improve milk safety. The approach emphasised appropriate material and delivery, business skills, and participatory monitoring [Citation21]. Training commenced in the district of Kamrup, where the state capital Guwahati is situated, and went on until 2011. In 2012, a second survey started, focusing on milk producers, traders and consumers with the goal to assess the impact of the training intervention. Here we report the findings from these two surveys and evaluate the impact of the hygiene training intervention on milk safety.

Material and methods

Two independent surveys were performed in 2009 and 2012 in Assam, India, () and consisted of questionnaires to assess knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) related to hygiene and disease, milk production and milk sales. In addition, direct observations were carried out using a checklist of hygiene of the farms, cows (Bos taurus or Bos indicus), milking utensils, hygiene of the premises, clothing, and milk containers.

2009 Survey

Milk producers, traders and sweet makers in four districts; Barpeta, Jorhat, Kamrup, and Sonithpur, were interviewed (). These districts were chosen purposively for their different characteristics. Kamrup contains the state capital Guwahati and is the major consumption centre. Jorhat is the second major city and consumption area. Barpeta had a high concentration of dairy producers, with surplus milk production, and supplied milk to Guwahati. Sonitpur also had a high concentration of dairy producers and good market access. Six wards per district were randomly selected from the list of wards and a list of all producers, traders, and sweet makers were created. Traders and producers were randomly selected from sampling frames of the district, whereas all identified sweet makers were included.

Table 1. Participants in the 2009 survey in Assam, India.

Training intervention

During the years 2009–2011, training was offered to milk producers and milk traders in Kamrup district. The training was free to attend for everyone that wanted to participate, and it focused on increasing the knowledge about food safety and hygiene. The intervention has been described in detail previously [Citation21].

2012 Survey

Data was collected from milk producers and traders in two of the districts that had been included in the 2009 survey, Kamrup and Jorhat, and the interviewed producers and traders were also asked if they had participated in the previous survey, or in the trainings (). Participants were randomly selected from both trained and untrained groups, using a stratified sampling: Among those that had been interviewed previously, both farmers and trader that had been trained as well as those who had not been trained were selected, and a similar selection was made among farmers and traders that had not been interviewed before. Among those that had not been trained or interviewed, we attempted to reach both farmers and traders that lived close to former participants, and those that lived further away. Thus, the 2012 survey consistent of participants that were both trained, and untrained.

Table 2. Producers and traders interviewed in 2012 in Jorhat and Kamrup district, Assam, India, in a study of the impact of a training intervention on knowledge and attitudes.

Detection of Escherichia coli in milk

The guideline for hygiene requirements for milk in Assam is that no Escherichia coli should be detected in milk diluted 100 times (personal communication, Dr. Saikia Microbiology Department, College of Veterinary Science, Assam Agricultural University). To test the presence of E. coli, milk and sweets were sampled in sterile vials. Samples were diluted tenfold and 0.01 ml was spread on flexiplates (Himedia) for coliforms, reaching a 100-fold dilution.

Data analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.2 (STATA corp, Texas, USA). The questions regarding attitudes and knowledge, as well as the observations about hygiene, were assessed using Cronbach’s alpha to find internal consistencies and if an underlying scale could be constructed, this was used to assess the association with other variables using t-test. The following categories were tested to see if there were internal consistencies: Hygiene (including udder cleanliness, clothes cleanliness, milk and milk containers free from dirt, hygienic manure disposal), knowledge (answering the questions if it is possible to get disease from milk or dung) and attitudes and believes. A Cronbach’s alpha scale was used if it was possible to optimize which variables to include and obtain an alpha above 0.70.

Differences in knowledge of disease transmission, or specific diseases were tested with univariable analyses, using Chi2, or Fisher’s exact test where applicable. Univariable analysis between percentage water added and attitude was assessed using t-test.

The comparisons between the results of trader and producer surveys from 2009 and 2012 were performed as if these were two independent cross-sectional surveys.

Results

Milk producers

In the majority of the 405 interviewed farms in 2009, the household head was male. Only 17 households (4.2%) had a female head. No buffaloes were present in any study farm. The number of adult cows in the households ranged from 1 to 110, with a mean of 15.5 (median 11). Similarly, the range of milking cows ranged from 1 to 32, with a mean of 8.3 cows in lactation (median 7) per household. The proportion milking cattle could be as low as 13% of the total number of adults.

Of the 162 milk producers interviewed in 2012, 88.3% reported a male household head, and 91.9% reported that the person in charge of the work with the dairy animals was male. No producer reported having buffaloes, and on average, a farm had 14.3 adult cows (median 12, range 1 to 72, standard deviation 10.3), with mean 9.0 cows in lactation (median 8). Approximately 2 out of 3 animals were currently in lactation (). There was a trend of decreasing numbers of cows per farm between 2009 and 2012, but with increasing proportion of cows in lactation.

Table 3. The number of dairy cows at farms in the survey in 2009 and 2012 in Assam, India.

Milk traders

Traders in 2009 were mainly men; only 3 out of 175 (1.7%) were female. All traders reported that milk was picked up between 4.30 and 10 in the morning and delivered until noon. On average, traders bought milk from 5.8 farmers, but this ranged between 0 (traders who were also producing milk) and 55. The traders reported never storing milk, but delivering it as soon as possible. Only 21 out of 175 reported ever throwing away milk because it got spoiled. Out of the 225 traders that participated in the survey in 2012, 122 (54%) had availed training. The median number of farmers the traders purchased milk from in 2012 was 1, and maximum 41.

Knowledge about diseases

In 2009, the knowledge about disease transmission was generally very low, with 13.0% (52/401) of producers, 9.1% (16/175) of traders, and 33.1% (40/121) of sweet makers believing that diseases can be transmitted by milk. There were significant differences (p = 0.047) between districts for the producers. In Kamrup 17.2% knew this, but in Jorhat only 4.7% knew. Even fewer believed that diseases could be transmitted by dung, only 2.7% of producers and 1.1% of traders (). In addition, the sweet makers were asked if they believed diseases could be transmitted through milk sweets, and this 57.6% (91/158) believed. Overall, 96% of the milk producers believed that milk is completely safe after boiling, but in Sonithpur only 82% believed this, significantly (p < 0.001) less than the other districts.

Table 4. Producer and traders interviewed in Assam, India, for their knowledge about disease transmission from milk and dung, and the belief if milk is safe after boiling. The results from comparison between the 2009 and 2012 surveys are shown, as well as the comparison between trained and untrained participants from the 2012 survey.

In both the analyses for traders and producers, significantly more people in 2012 believed it was possible to get diseases from milk or cow dung (). This indicates that the training intervention was associated with a clear improvement of the knowledge. However, there was also a significant difference between the producers in 2009 and the untrained producers in 2012 both regarding believing that disease could be transmitted from dung (p < 0.001) and from milk (p = 0.03). For traders, there was only a significant difference regarding the knowledge of disease transmission from dung (p < 0.001) for untrained participants in the two surveys.

Sweet makers were only included in the 2009 survey. There were significant differences between districts as to the knowledge about the risks of sweets. 121 answered the question if people could sick from milk, and in total 33% believed this, but Barpeta had significantly lower knowledge than the other districts, with no sellers believing it. This was similar to when sellers were asked if they believed people can get sick from milk sweets. In total 91 out of 158 (57.6%) believed this, but no sellers in Barpeta. All believed that boiling made milk completely safe. There were no underlying internal consistencies among the attitudes questions nor the knowledge questions when tested with Cronbach’s alpha.

When traders and producers were asked which diseases could be transmitted by raw milk, gastrointestinal disorders (dysentery, gastritis, vomiting, diarrhoea, and gastroenteritis) were the most common answers in both surveys. Non-gastrointestinal symptoms listed were fever, cold, cough and headache. Worm infections were also common answers, and analysed separately from gastrointestinal disorders. The most commonly mentioned specific disease mentioned was tuberculosis. Four producers interviewed in 2012 mentioned cancer, one typhoid and one brucellosis. Only one producer 2009 mentioned cancer, and no further specific disease beyond tuberculosis was mentioned.

Specific diseases, apart from tuberculosis, mentioned by traders in 2012, were cholera, mentioned by three traders, and anthrax and jaundice, which were mentioned by one trader each. In 2009, no other specific disease than tuberculosis was mentioned by traders ().

Table 5. Diseases that can be transmitted by milk suggested in two surveys among milk producers and traders in Assam, India.

Attitudes and beliefs

There was a strong trend for respondents to feel that it is possible to tell if milk is safe by sight or taste, and that a little dirt is not harmful. However, the majority did not agree that costumers would prefer cheap milk, instead of good quality. Most people believed it were good for a cow to add water to its milk, and that the manure was sacred ().

Table 6. Attitudes and believes regarding milk hygiene among milk producers, milk traders and sweet makers in Assam, India.

Hygiene

Milk producers

All producers in 2009 reported that they most often used cold water when washing their hands, but two also reported using hot water. Out of the 405 producers, 394 (97.3%) reported using soap frequently and no one reported frequent use of ash, soil or disinfectants. The 11 producers (2.7%) that reported not using soap regularly were all in households with a male household head, and these respondents did not believe dung could transmit diseases. There was no correlation between using soap and agreeing to the statement that a few specks of dirt would not be harmful.

In 2012, only 9 producers used hot water, and 106 reported that they used soap most often. One producer reported using soil regularly to clean hands, but no one used ashes. Similar to in 2009, only 3 (5.4%) out of the 56 that did not use soap believed dung could transfer diseases, while more than 50% of those using soap believed this (p < 0.001).

There were significant differences in hygiene between the different districts (). In Sonitpur, the majority of the producers (60.76%) had cows with clean udders, but no one was judged to have a hygienic manure disposal system, and a low proportion of clean and whole milk containers compared to the other districts. Only 6.9% of the farmers in Barpeta were judged to have hygienic manure disposal system, and in the other three districts the percentage was even lower. In terms of milk free from dirt, Barpeta had the highest proportion, followed by Sonitpur, Jorhat and Kamrup (). Milk containers were also found to be the cleanest in Barpeta. The percentage of farmers having clean clothes was less than 12% across the districts but the training brought significant improvement on this in the project districts Kamrup and Jorhat ().

Table 7. Observations regarding cleanliness and hygiene among milk producers, milk traders and sweet makers in 2009 and 2012 in Assam, India.

Milk traders

In 2009, only one trader, in Kamrup, reported using hot water, the rest only used cold water to clean hands. All traders in Barpeta, Jorhat and Sonithpur used soap, but only 75/84 (89.3%) in Kamrup. All milk observed in Barpeta was judged to be free from dirt, and all clothes were clean, which was significantly better than the other districts. It was not possible to identify underlying internal consistencies between the hygiene questions using Cronbach’s alpha.

In 2012, significantly (p = 0.005) more traders in Kamrup had clean clothes compared to Jorhat (). Three traders in Kamrup reported using hot water, and 26/34 in Jorhat and 163/192 in Kamrup used soap.

Sweet makers

Only seven sweet sellers reported using hot water regularly to clean their hands. All reported using soap, apart from two in Kamrup. There were significant differences in the proportion of sweet sellers that wore clean clothes, with the highest proportions in Barpeta and Kamrup ().

There was a strong internal correlation (alpha = 0.75) among the hygiene observations related to cleanliness: whether garbage cans had lids and were clean, all surfaces in contact with food being clean, the cloth for wiping was clean and no insects within the premises, and a scale representing cleanliness was created. There were significantly higher scores on the scale among sweet makers that believed that milk could transmit disease (0.35 scores higher, p < 0.001) and that diseases could be transmitted by milk sweets (0.42 scores higher, p < 0.001).

Milk quality

Milk producers

Samples from 268 producers, only from Jorhat and Kamrup, were tested for presence of E. coli in milk in 2009, of these all samples from Jorhat contained E. coli, whereas 3.6% of samples from Kamrup were negative. In addition to the bacteriological testing, milk from 130 producers was tested for presence of added water, and it was found that this varied from 0 to 54%, with a mean of 16.9% (95% confidence interval 14.6–19.1%). Significantly more water was added in Kamrup (mean 21.3%) compared to Jorhat (mean 8.4%) (p < 0.001). There was no association between the belief that it would be good for the cow to add water and the percentage of added water in the milk.

In 2012, coliforms were analysed from 180 samples, of which all were positive. In total 193 samples were analysed for added water, and 33.3% of samples from Jorhat, and 58.6% of samples from Kamrup (p = 0.002) were judged to contain added water (). The maximum added water was judged to be 28%.

Table 8. Laboratory results from analyzed milk from milk producers and milk traders in 2009 and 2012 in Assam, India.

Milk traders

Samples from 111 traders, only from Jorhat and Kamrup, were tested for growth of coliforms and added water in 2009. No sample was negative for coliform growth (). Up to 55% water had been added to the milk, and there was a mean addition of 20.6% (95% confidence interval 18.2%-22.9%). Significantly higher proportions of water were added in Kamrup (23.6%) compared to Jorhat (11.2%) p < 0.001. There was no association between more water added to the milk and the belief that it was good for the cow to add water. In 2012, all samples also contained E. coli, and up to 21% water added was detected in Jorhat, and 31% in Kamrup. The proportion of trader samples that contained added water was also significantly higher in Kamrup compared to Jorhat (p = 0.03).

Sweet makers

For laboratory testing, 190 sweet samples were collected in 2009 and all of these were positive for coliform growth at a dilution of 100.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge, attitudes and practices along the informal dairy value chain in Assam, India, from the farmers to the sweet sellers. Overall, a very low level of knowledge regarding zoonotic diseases and milk-borne hazards was observed, among all actors, and attitudes indicated that value chain actors are not considering hygiene important. This is contradictory to the results by Sarma et al. [Citation22], who studied the knowledge of dairy farmers in Assam and reached the conclusion that their knowledge was medium to high, but there is no information in their report regarding what the questions were, or what level the questions were on.

The knowledge of different milk-borne diseases was generally higher in 2012 compared to 2009, except for knowledge about worms, where there was no difference for traders. All trained traders were significantly more knowledgeable than the untrained counterparts, and the same was true for producers, except concerning worm transmission. In some instances, general disease symptoms for traders and gastrointestinal disease for traders, significantly more untrained respondents in 2012 mentioned diseases, than were mentioned in 2009. Cancer was occasionally mentioned. One mechanism through which milk could cause cancer can be through aflatoxins, a heat-stable toxin produced by fungi in the cows feed, and which has been detected to a large extent in Indian commercial milk [Citation23]. However, only one of the producers that mentioned cancer also knew that milk was not safe after boiling, implying that knowledge about aflatoxin cannot be behind these answers. Mentioning of non-gastrointestinal symptoms was generally uncommon, but this knowledge may indicate a greater understanding of zoonotic transmission.

Bacterial risks with raw milk in India has been shown in previous studies, including Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Brucella spp, mycobacteria and Staphylococcus aureus [Citation17–Citation19]. Although brucellosis is believed to be highly endemic in India, it is likely to be underdiagnosed [Citation18,Citation24], and the few single participants who mentioned the disease confirms that it is not widely known and acknowledged. In contrast, tuberculosis seemed better known.

During hand milking the producers are in very close contact with their animals, which increases the risk of transmission of disease from an animal. One major source of disease-causing bacteria is the faeces from the cow, and the milkers are likely to be highly and repeatedly exposed to this through their close contact. Bacteria present in cattle faeces may include salmonella, toxin producing E. coli etc. The risk of transferring bacteria from the milker to the milk itself is much higher during hand milking than when milking is done by machine [Citation16], and hand milking is the main mean of milking in rural India. This study showed that only few of the farmers believed that diseases could be transmitted by cow dung, which may influence the precautions farmers take to avoid getting infected themselves, and the measures they take to avoid contamination of milk. In this study it was shown that cold water, combined with soap, was the most common mean of washing hands. No data was collected on the origin of the water, and it has been shown that water stored in tanks may contain much higher levels of bacteria than tap water [Citation25]. Whereas udder and teats are likely the major sources of contamination, the hands of the milkers may contribute as well. It has experimentally been shown that when hygienic practices are followed, the contamination with Staphylococcus aureus was significantly reduced [Citation25].

Overall, this study shows a low awareness of milk-borne pathogens, which could likely engender dairy production and milk handling practices that may compromise quality and safety in milk being traded in informal markets. Training did have an effect on the knowledge of both traders and producers, but there might also be effects of knowledge dissemination from trained people and a general increase in awareness, as an improvement over time was also observed in untrained participants. The importance of milk production for the livelihood of small-holders, as well as the importance of milk as a source of nutrients, makes it imperative to put milk safety and quality as priority policy issues in dairy production in Assam.

It is a common misperception that milk is completely safe after boiling. Depending on the handling after boiling, milk can easily get recontaminated, and there are also contaminants that will remain in the milk during boiling. In addition to aflatoxins, many toxins produced by pathogens are heat-stable, such as the enterotoxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus, and heat-resistant spore-producing bacteria, such as Clostridium perfringens and Bacillus spp, can persist after pasteurization start growing if milk is not kept cold, and the latter can be commonly present on udder surface and in milk cans [Citation16,Citation20]. There are a also number of thermoduric non-pathogenic bacteria [Citation16] which contribute to milk spoilage. Our study shows that this perception is hard to change, although trained producers had better knowledge than untrained producers, while more traders in 2009 knew about these risks than untrained trainers in 2012. However, the fact that there is a strong belief that boiled milk is safe may make people more prone to keep boiling properly, which would help prevent most milk-borne diseases.

This study reveals some common beliefs surrounding dairy production in India. Cattle dung has long been considered healthy and beneficial, but it was clear that training introducing the concept of pathogens is capable of increasing the knowledge levels and make people more aware of this. Similarly, there are occasionally cultural beliefs that the cow can be affected by what is done to the milk after milking. Here, there was a common perception that it could be good for the cow to add water to the milk, which also was improved after training.

The improvement in knowledge observed in the 2012 survey also among untrained respondents indicates that the general knowledge has been increasing during these years, even if no training is attended. One explanation for this could be that training a part of the population raises the general awareness and the knowledge disseminates. The project also engaged in several media and community events to raise general knowledge, which might have influenced these results, and may have biased comparisons between trained and untrained groups towards null. However, improved knowledge may not be enough to change practices and make people invest in protective measures. A study on lymphatic filariasis indicated that knowledge about the biological cause of disease may not be as important for willingness to pay for prevention as information about the risks [Citation26]. It may therefore be good to include more risk awareness into future training interventions.

In order to succeed in interventions in a value chain it is important to consider the whole system and to see the linkages between food safety and health, and between knowledge and practice and also to see the importance of traditional small holder dairy in the society. To reach sustainability it is further important to work with participatory approaches and find the incentives that give sufficient motivation for lasting change.

This study has several limitations. The initial design aimed at comparing the same individuals in both surveys was abandoned when the linking codes between the two surveys were lost, which caused the analyses to be used as two separate cross-sectional surveys. If it had been possible to have the actual bacterial counts, as was the original plan of the project, it might have been possible to detect a difference in the level of bacterial contamination between the two groups, which was not possible to detect when only looking at the proportion of samples positive for bacteria in a 100-fold dilution, since such a high proportion was positive. However, it is not unreasonable to believe that the impact was larger on knowledge than on contamination, especially since we could not show as large effects on practices as on knowledge.

Milk production is important for the livelihood of many value chain actors, but the productivity of Indian cows may be low, even of the cross-breeds (ILRI, 2007). Although the milk production in Assam has been increasing, the increase has been slow, and during the study period 2009–2012 milk production only increased from around 750,000 tonnes, to 800,000 [Citation9]. Increasing the efficiency and safety of the milk production is important for many aspects; it improves the food security for the poor households, safeguards their health and creates better possibilities for making a living. In addition it may also reduce the greenhouse gas emissions per unit milk produced [Citation27].

In conclusion, this study shows that single interventions have impact in changing the knowledge and attitudes, and may therefore have long term benefits in terms of increased food safety and increased productivity. Overall, this study shows a low awareness of milk-borne pathogens, which could likely contribute to practices in the dairy production and milk handling that may compromise quality and safety in milk being traded in informal markets. The importance of milk production for the livelihood of small-holders, as well as the importance of milk as a source of nutrients, makes it imperative to put milk safety and quality as priority policy issues in dairy production in Assam. The conclusions of this study are that the knowledge levels in regards to hygiene and disease was very low among the dairy producers and traders in Assam.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the local partners; Dairy Development Department, Assam Agricultural University, and Greater Guwahati Cattle Farmers Association. This study was funded by Department for International Development (DFID) & The OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), with support from CGIAR research program on Agriculture for Nutrition and health and support from all donors to the CG system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johanna F. Lindahl

Johanna F. Lindahl is a veterinary epidemiologist working at International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi Kenya, and adjunct at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and Uppsala University. Johanna graduated from Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences after doing her PhD working on Japanese encephalitis virus in Vietnam. Since her PhD she has been focusing her research on food safety, and vector-borne, zoonotic and emerging infectious diseases in developing countries, mainly East Africa and South and Southeast Asia. In addition to this, she is coordinating a number of aflatoxin projects within ILRI.

ILRI is part of the CGIAR consortium and works with partners worldwide to enhance the roles that livestock play in food security and poverty alleviation, principally in Africa and Asia and is a member of the CGIAR Consortium, a global research partnership of 15 centres working with many partners for a food-secure future. ILRI headquarters is in Nairobi, Kenya with a principal campus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and offices in East, West and Southern Africa and South, Southeast and East Asia.

Ram Pratim Deka

Ram Pratim Deka is a scientist at ILRI based in the office in Guwahati, Assam, India. He has a MSc in veterinary medicine, and also a MBA degree. He is working in many projects including zoonotic diseases, food safety and accelerating the dairy and pig value chains in the Northeast India region.

Rainer Asse

Rainer Asse is a social scientist who worked with ILRI on projects in Asia during many years.

Lucy Lapar

Lucy Lapar is an agricultural economist, working with ILRI in many years based in Asia. Her work focuses on supporting and enhancing decision-making processes and institutions for smallholder competitiveness and participation in livestock markets. She holds a Ph.D. in agricultural economics from Ohio State University. Prior to joining ILRI, she was a postdoctoral scientist with the International Rice Research Institute, working in rice-based upland systems to investigate soil conservation adoption and impacts. Dr. Lapar has wide expertise in her field, including the application of discrete choice models in livestock production, consumption and marketing; impact assessment of technology adoption; design and implementation of household surveys; and agricultural economics.

Delia Grace

Delia Grace is an epidemiologist and leads the Health Program at ILRI and the Flagship on Food Safety in the CGIAR research program on agriculture and health. She has been a lead researcher in food safety in informal markets for several decades. She has led or contributed to evidence syntheses and investment advice for World Bank, DFID, USAID, ACIAR, BMGF, FAO, OIE, WHO, AU-IBAR, OECD and others.

References

- Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR. World health organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med. 2015 Dec;12(12):1.

- Rosegrant MW, Ringler C, Zhu T. Water for agriculture: maintaining food security under growing scarcity. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2009;34:205–10.

- Grace D, Mahuku G, Hoffmann V, et al. International agricultural research to reduce food risks: case studies on aflatoxins. Food Secur. 2015 May;7(3):569–582.

- Grace D. Food safety in low and middle income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015 Jan;12(9):10490–10507.

- WHO. Diarrhoeal disease. [Online]. cited 2018 Oct 30. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease

- McDermott J, Grace D. Agriculture-associated diseases: adapting agriculture to improve human health. In: Fan S, Pandya-Lorch R, editors. Reshaping Agric Nutr Heal. Washington (DC): IFPRI; 2012. p. 12–103.

- Delgado CL. Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution. J Nutr. 2003 Nov;133(11):3907S–3910S.

- FAOSTAT. Milk total production in India. 2015. [Online]. cited 2015 Apr 12. Available from: http://faostat3.fao.org/browse/Q/QL/E

- NDDB. National dairy development board statistics. 2018. [Online]. cited 2017 Jul 03. Available from: http://www.nddb.org/information/stats/

- Douphrate DI, Hagevoort GR, Nonnenmann MW The dairy industry: a brief description of production practices, trends, and farm characteristics around the world. J Agromedicine. 2013 Jan;18(3):187–197.

- Singh PN, Arthur KN, Orlich, MJ. Global epidemiology of obesity, vegetarian dietary patterns, and noncommunicable disease in Asian Indians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Jul;100(Suppl_1):359S–64S.

- Census of India. 2011 census data. [Online]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.html

- Govt of Assam. Economic Survey, Assam 2012-13. 2013.

- Kumar A, Staal SJ. Is traditional milk marketing and processing viable and efficient? An empirical evidence from Assam, India. Q J Int Agric. 2010 Jul;49(3):213–225.

- ILRI. Comprehensive study of the Assam dairy sector: action plan for pro-poor dairy development. 2007.

- Chambers J. The microbiology of raw milk. In: Robinson RK, editor. Dairy microbiology handbook: the microbiology of milk and milk products. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Wiley; 2005. p. 39–90.

- Lingathurai S, Vellathurai P. Bacteriological quality and safety of raw cow milk India. Webmedcentral Microbiol. 2010;1(10):1–10.

- Smits HL, Kadri M. Brucellosis in India: a deceptive infectious disease. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:375–384.

- Kumar B, Rai R, Kaur I, et al. Childhood cutaneous tuberculosis: a study over 25 years from northern India. Int J Dermatol. 2001 Jan;40(1):26–32.

- Thomas M, Siji PC, Prejit E, et al. Milk borne bacterial zoonoses. Intas Polivet. 2006;7(2):212–218.

- Lindahl JF, Deka RP, Melin D. An inclusive and participatory approach to changing policies and practices for improved milk safety in Assam, northeast India. Glob Food Sec. 2018;17:9–13.

- Sarma J, Ray M, Saharia K. Knowledge level of the dairy farmers in Kamrup district of Assam. Indian J Hill Farming. 2011;24(1):11–14.

- Rastogi S, Dwivedi PD, Khanna SK, et al. Detection of Aflatoxin M1 contamination in milk and infant milk products from Indian markets by ELISA. Food Control. 2004 Jun;15(4):287–290.

- Renukaradhya G, Isloor S, Rajasekhar M. Epidemiology, zoonotic aspects, vaccination and control/eradication of brucellosis in India. Vet Microbiol. 2002 Dec;90(1–4):183–195.

- Pandey N, Kumari A, Varma AK, et al. Impact of applying hygienic practices at farm on bacteriological quality of raw milk. Vet World. 2014 Sep;7(9):754–758.

- Rheingans RD, Richard D. Anne C. Willingness to pay for prevention and treatment of lymphatic filariasis in Leogane, Haiti. Filaria J. 2004;3(1):2.

- Herrero M, Havlík P, Valin H. Biomass use, production, feed efficiencies, and greenhouse gas emissions from global livestock systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 Dec;110(52):20888–20893.