ABSTRACT

Background: The relative efficacy and safety can vary among drugs over time. Sumatriptan, a first choice drug for acute migraine, can illustrate this phenomenon.

Objective: To assess the evolution of the relative efficacy and tolerability of oral sumatriptan against placebo between its approval in 1991 and 2006.

Methods: A systematic literature review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adults suffering from acute migraine episodes was performed using Medline. Meta-analyses estimated odds ratios of the occurrence of pain-free at 2 hours and of any adverse event.

Results: Out of the 67 RCTs identi.fied, pain-free at 2 hours and adverse events were reported in 25 and 28 studies, respectively. For pain-free, the relative effect of sumatriptan increases considerably over time, despite an increase in the absolute placebo effect. The odds ratio (95% CI) equaled 3.13 (1.67–5.86) around approval (1991–1994) and increased up to 4.14 (3.67–4.67) on the following decade. No specific variation was observed in the relative tolerability effect of sumatriptan over placebo over time.

Conclusions: The relative effect of sumatriptan evolved substantially over time. This phenomenon may impact the results of network meta-analysis and indirect comparisons performed to evaluate the potential of a new drug, compared to widely prescribed older drugs.

Introduction

When introducing a new drug into the market, it is necessary to submit evidence about its efficacy, safety and tolerability profile. In the course of the registration process, several clinical studies are performed to evaluate the benefit/risk ratio. The new drug will be typically tested over a placebo control, but may be also assessed versus an active reference drug to confirm assay sensitivity.

Few studies have shown that overall the estimated relative efficacy of widely used drugs varies substantially over time whereas the absolute effect of the drug is not supposed to vary substantially. Llorca et al. [Citation1] demonstrated an improved relative efficacy and safety of the antidepressant escitalopram vs. other antidepressants over time, using change from baseline to 8 weeks on Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score, and withdrawals due to adverse events. Variations in the relative efficacy over time on two critical outcomes for assessing drug relativeness effectiveness were also identified for tiotropium, a reference treatment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation2]. The difference was observed depending on whether the drug was used as investigational or comparative arm.

When randomized controlled trials (RCTs) include an active comparator arm, patients who previously received the comparator drug and did not respond to it are usually not selected for participation in the trial or formally excluded. This exclusion is justified on ethical grounds but may create a selection bias. The issue is particularly problematic when network meta-analysis or indirect comparisons are subsequently performed, since this exclusion criterion may have a different impact in the earlier trials using an active comparator than in the later trials using the same comparator [Citation3]. For example, when a drug became the Standard of Care after its introduction, the proportion of patients who are exposed to the comparator medication will increase over time, and thus the selection bias may become significant. Therefore the relative effects of newer drugs will be compared unfavorably versus the relative effect of older drugs. The Regulatory Authorities have recognized this selection bias. In their assessment of vortioxetine (Brintellix), where exclusion of the non-responders to the active reference duloxetine was an exclusion criteria, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) acknowledged in European public assessment report (EPAR) for Brintellix that ‘The exclusion of non-responders and the inclusion of previous responders in the active reference arm could have introduced a bias in favor of the efficacy of the active reference, so differences in the efficacy of vortioxetine versus the active reference cannot be inferred on the basis of these studies’ [Citation4].

This study aims to examine this phenomenon in another disease area. Migraine was identified as a potential area of interest, as a highly prevalent disease, with a considerable number of trials performed versus placebo and the same active comparator, sumatriptan, steadily been used as a reference treatment over time for acute migraine episodes [Citation5]. The objective of this study is then to assess the evolution of the relative efficacy and tolerability in double-blind randomized clinical trials of oral sumatriptan against placebo, since launch and the latest assessment.

Methods

Data source and study selection

A systematic literature review of RCTs of adults suffering from acute migraine episodes was performed using Medline. The search was conducted via the Ovid interface in July 2013, using the keywords related to migraine, headache disorders or cephalgia, and sumatriptan. The following limits/restrictions were used: enrolled patients with acute migraine episodes; age group ≥18 years old; randomized controlled trial; included a placebo control group; reported in English; reported proportion of patients with pain-free at 2 hours as a measure of efficacy and/or reported proportion of any adverse events as a measure of tolerability (see ). The search was conducted for the period from and shortly after approval (1991) to the following 15 years (up to 2006). This way of analyzing the data was consistent with the health technology assessment (HTA) agency perspective as the entire set of evidence is considered at time of evaluation.

Studies were excluded if they did examine the use of sumatriptan as a prophylactic treatment, or if they included <30 patients per treatment group.

Two analysts reviewed titles, abstracts and finally full texts of the qualifying articles to determine whether they met inclusion/exclusion criteria. Any discrepancy regarding study eligibility for which a consensus was not achieved was reviewed by a third independent researcher.

Only treatment arms including sumatriptan approved 100 mg oral dose, selected as the most effective standard dose, and placebo were included in the analyses [Citation6].

Outcomes of interest

Efficacy was evaluated as the proportion of patients with pain-free at 2 hours, which is the primary efficacy endpoint recommended by the International Headache Society (IHS) for clinical trials for acute treatments of migraine, as it aligns with patient satisfaction and is less subject to placebo effect [Citation7]. Pain-free was defined as a headache pain reduced from moderate or severe at baseline to none at 2 hours after dosing. Headache pain was recorded by the patient using a four-point Likert scale (i.e., 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe), as recommended by the clinical guidelines [Citation8].

Any study without reported pain-free at 2 hours data was not considered in this review, including the ones that reported headache relief at 2 hours, or pain-free at 4 hours.

In addition to the efficacy endpoint, a tolerability endpoint was also considered: tolerability was defined as the proportion of patients with any adverse events (AEs) after initial dose of treatment, out of the total number of patients randomly assigned to sumatriptan or placebo and who received at least one dose of treatment.

Statistical analyses

For the first step, as a qualitative analysis, efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan 100 mg over time were presented using the mean differences to placebo (sumatriptan-placebo difference scores). The publication date was used as a proxy of the clinical trial assessment if not reported. The trend in the relative efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan over placebo over time was illustrated using the linear least squares fitting technique. Absolute efficacy and tolerability outcome results in the sumatriptan active treatment arm and the placebo arm were also shown over time, to characterize the trend in the sumatriptan-placebo differences over time.

As a second step, meta-analyses were performed using the inverse-variance weighted average method (fixed effect model) described by Sutton et al. [Citation9] and Thompson et al. [Citation10] to estimate the odds ratios of the occurrence of pain-free at 2 hours and of any adverse event, based on available RCT data from launch in 1991 to 2006 on a yearly basis. The goal was to provide quantitative summaries of clinical trials data performed between the launch of oral sumatriptan to the following 15 years (up to 2006). Meta-analyses were implemented to compare the group treated with sumatriptan and the control group given placebo in terms of two outcomes: pain-free at 2 hours for efficacy and any adverse events for tolerability. The aim was to illustrate the year-to-year re-evaluation of a drug according to all previous clinical trials performed. Outputs generated from these analyses were presented as odds ratios of the occurrence of pain-free at 2 hours and of the occurrence of having any adverse event by period.

As a last step, increases in odds ratio of the occurrence of pain-free at 2 hours estimated by time period compared to 1991–1994 launch period were assessed, and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method was used to test the linear relationship between estimated odds ratio increases and time periods.

All analyses were performed by one statistician, and quality control was conducted by another.

Results from analyses were then compared, and any discrepancies were resolved by program examination by the statisticians.

Results

describes the process for inclusion of articles in the analysis, in agreement with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation11]. Of the 63 publications selected by this process, four reported the results of two different trials [Citation12–Citation15]. Thus, a total of 67 trials were selected as potential relevant RCTs for the analysis.

Efficacy assessment

Of the 67 RCT studies, 25 studies included a placebo and a sumatriptan 100 mg treatment arms, with available data on the proportion of patients with pain-free at 2 hours in the two arms.

Hence, 25 studies were selected for the efficacy evaluation to compile the results of acute migraine clinical trials published between 1991 and 2006, that included 9627 patients with migraine (with 5601 patients assigned to sumatriptan 100 mg and 4026 assigned to placebo). The list of references to these studies is available in Appendix B.

Qualitative description of the relative efficacy of sumatriptan versus placebo over time

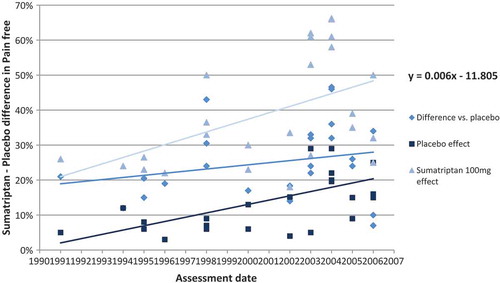

The magnitude of sumatriptan–placebo differences over 15 years after launch was first evaluated, as shown in .

Figure 2. Correlation of sumatriptan–placebo differences (difference between sumatriptan and placebo groups in the proportion of patients with pain-free at 2 hours) with the year of assessment.

A considerable increase in absolute placebo effect was observed between the launch of sumatriptan and later assessment. Assuming a linear placebo effect over time, the proportion of patients with pain-free evaluated in the RCTs increases from around 5% to 20% in 15 years.

Despite this increase in the absolute placebo effect, the relative effect of sumatriptan was found to increase over time. With a linear effect assumption over time, the sumatriptan-placebo differences observed in the RCTs increased by about 10 percentage points within 15 years after drug launch (1991).

This result confirms a positive correlation between the relative effect of sumatriptan versus placebo and the time of evaluation.

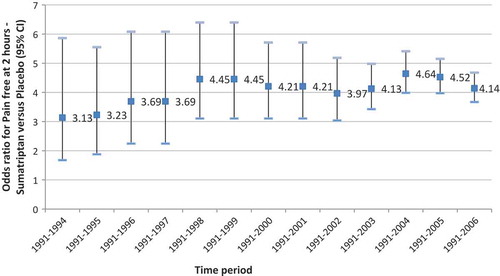

Meta-analysis – trend over time of the relative efficacy of sumatriptan versus placebo

presents the odds ratios for occurrences of pain-free at 2 hours of sumatriptan versus placebo, estimated from meta-analyses of RCT data published within the different time periods (from period 1991–1994 to period 1991–2006).

The relative efficacy of sumatriptan versus placebo varied considerably over the different time periods. By adding RCT data from 1995 to 1999 in the meta-analysis, the estimated odds ratio [95% CI] was increasing from 3.13 [1.67–5.86] (1991–1994) to 4.45 [3.10–6.40] (1991–1999). It decreases to 3.97 [3.04–5.18] by including RCT data published until 2002 (1991–2002). The maximum odds ratio estimated was 4.64 [3.98–5.41], attained using efficacy data of RCTs published until 2004 (1991–2004). Finally, based on the 25 studies selected in our review and published from 1991 to 2006, the odds ratio for the occurrence of pain-free with sumatriptan compared with placebo was estimated at 4.14 [3.67–4.67], or a 32% increase compared to the first estimation based on RCT data from 1991 to 1994.

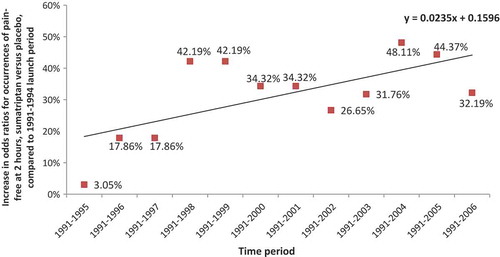

Estimated increases in odds ratios for occurrences of pain-free at 2 hours, sumatriptan versus placebo, compared to 1991–1994 launch period, are shown in . The ANOVA indicated the significant positive slope of the regression line (p = 0.0232).

Tolerability assessment

Twenty-eight studies (10,162 patients) reported the probabilities of numbers of patients with any adverse event from the launch of sumatriptan from 1991 to 2006. The list of references to these studies is available in Appendix C.

Qualitative description of the relative tolerability of sumatriptan versus placebo over time

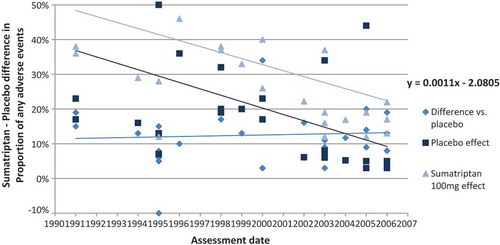

shows the sumatriptan–placebo differences obtained in trials, by year of publication.

Figure 5. Correlation of sumatriptan–placebo differences (difference between sumatriptan and placebo groups in proportion of patients with any adverse events) with the year of publication.

Both the absolute placebo effect and the absolute sumatriptan effect declined over 15 years after launch. The magnitude in a decrease of adverse events over time was comparable in both treatment groups, as illustrated by the parallel linear trend lines.

Therefore no significant variation was observed in the relative difference in tolerability over the years, using the occurrence of an adverse event as the tolerability outcome. Assuming a relative linear effect over time, the sumatriptan-placebo difference remains stable at around 12% from launch to the latest evaluated assessment.

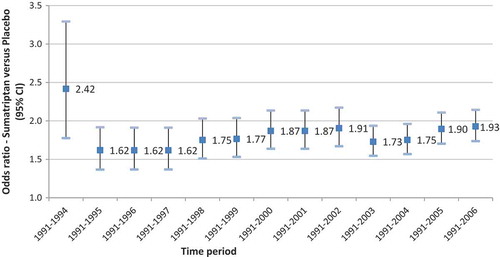

Meta-analysis – trend over time of the relative tolerability of sumatriptan versus placebo

The odds ratios for occurrences of adverse events of sumatriptan versus placebo, estimated from a meta-analysis of RCT data published within a period (from the launch of sumatriptan to year Y) are presented in .

No apparent variation in the risk of adverse event compared with placebo over time was evaluated using the successive meta-analyses of available RCT data from launch to the latest assessment.

Discussion and conclusions

This study aimed to assess the evolution of the relative efficacy and tolerability of the reference treatment in the prevalent migraine disorders disease – sumatriptan – between launch and later assessment. It was stated as a hypothesis that the potential improvement in relative effectiveness and tolerability overtime for drugs widely used could be linked to the exclusion of previous non-responders to the selected drugs, or non-inclusion of patients expected not to respond according to clinician judgment.

We found that the relative effect regarding efficacy of sumatriptan vs placebo increased between launch and later assessment. The average sumatriptan-placebo difference was approximately evaluated at 20% using the pain-free at 2 hours outcome in 1991 compared to an average of about 30% in 2006, based on published sumatriptan trials. These data confirmed the hypothesis of a positive relationship between the relative effectiveness of sumatriptan in comparison to placebo and the time of evaluation.

Such variability in the relative effect of widely used drugs after the market access can be explained by the differences in study design of post-marketing trials, compared to the design of the registration trials. It is expected that among the post-marketing trials, some trials will be profiling studies in patient subgroups in which the new drug is expected to demonstrate a better effect. The inclusion of post-marketing RCT data which demonstrated a higher benefit in a specific selected patients’ subgroups for migraine treatment may then affect the ranking in the following years after launch, with a trend to improve.

Other factors that could have influenced the variability in the relative effect include the change in the management of migraine and potential bias in study selection. However, while sumatriptan came to be one of the most important therapeutic advances in migraine, after its discovery, other triptans entered the market over time. These new triptans presented minor changes in the original molecule’s pharmacology and pharmacokinetics, but, on balance, the triptans acted similarly and lead to similar outcomes. In addition, the randomization would alleviate most of the effect of a change in the management of migraine. For the study selection, we conducted a systematic literature review that did not identify specific bias – the number of non-included studies did not follow a specific pattern that could have influenced the results.

Changes in the treatment guidance and practice can also influence the results obtained in different periods of time of assessment. Therefore it is essential to take precautions when assessing the evolution of the effect of a drug over time.

We did not find any evident variation in the relative tolerability of sumatriptan over time. Both absolute sumatriptan and placebo effects regarding adverse events decreased between launch and later assessment, with a similar trend over time. A lower variability on the tolerability can be expected as it was previously reported by Llorca et al. [Citation1], who stated that ‘Typically, any variation in the tolerability of drugs should not be as prominent as for efficacy as it is expected that drugs will have similar tolerability profiles across slightly varying patients’ populations or disease’s characteristics.’ The decrease in the tolerability odds ratio estimated from 1991–1994 time periods to all other time periods may be linked to the Weber effect. As sumatriptan was a completely new class of drug, patients and physicians may have been more alert to new side effects. As the drug started to be more widely used and known, the reporting may have decreased post-launch. Further research should be done to explore this effect, as the Weber effect has become more controversial in recent studies [Citation16,Citation17].

To our knowledge, no similar study assessing the variation of relative efficacy and tolerability of a reference treatment in comparison to placebo over time was previously published. However, the increase in placebo responses over time has been already demonstrated by a study conducted at McGill University in Montreal in US clinical trials of neuropathic pain published between 1990 and 2013 [Citation18]. Based on patient-reported pain outcomes, the relative pain reliever effect of painkillers versus placebo was evaluated at 27% in 1996, versus only 9% in 2013. This significant increase in placebo responses was driven by the US trials. Possible explanations are direct-to-consumer advertising for drugs allowed in the US, creating a stronger placebo effect, but also the more extensive and more costly US trials with a higher implication of nurses and the broader influence of the effect of the drug to their dedicated patients versus smaller trials.

It is important to note that this study is a preliminary research for evaluating the hypothesis that the potential improvement of relative effectiveness and tolerability overtime for drugs widely used could be linked to the exclusion of previous non-responders to the selected drugs. However, the present study has several considerable limitations. Thus, for several reasons, our analyses suggest directions for further research rather than firm conclusions.

First, the literature review used to identify the RCTs was a focused literature review in Medline. The methodology was systematic but should be extended to a search in other databases including at least Embase and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Including data from unpublished sumatriptan trials would also increase the quality of the systematic review.

Second, although the analysis of the relative efficacy supported our primary assumption, it would be essential to evaluate different factors that may be related to changes in sumatriptan–placebo differences. With this objective, we could suggest the use of meta-regressions models to identify the various factors that have significant associations with the sumatriptan-placebo pain-free difference. Covariates such as inclusion and exclusion criteria, research design features and characteristics of the population (e.g., mean age, gender ratio, baseline severity) could impact the relative effects, such as the exclusion of non-responders to the reference drugs. This analysis will, however, present some challenges, as the change in patient populations participating in clinical trials across the years, such as the exclusion of non-responders or non-tolerable patients to the reference drug is not always reported in the publication.

Lastly, assessing the evolution over time of the relative effectiveness of sumatriptan should be evaluated using other efficacy outcomes. Some of our preliminary analyses suggest the increase in relative recurrence at 2 hours over time. But the results need to be contrasted to the one in headache relief, where the relative effect of sumatriptan decreased over time, partly explained by a considerable increase in the placebo effect. The subjective aspect of pain relief might also affect the outcome assessment.

To conclude, these results demonstrate that the time from market access may not be the most appropriate time to evaluate the relative effectiveness and tolerability of new drugs. Due to the limited value evidence collected for new drugs compared to widely used older drugs, the comparison may be biased. Also, sufficient time is needed to capture all of the benefits of a new therapy, and this may not be sufficiently revealed until post-registration additional data are collected [Citation2]. Finally, publication and selection bias may have an impact on the current methods of comparison. It is therefore of great importance to reevaluate a drug over time.

However, as it is essential for HTA agencies and other decision-makers to evaluate a new drug compared to other therapies at the time of launch, one critical recommendation would be to assess the comparison using RCT data with very similar design features and patient characteristics, such as using the data from pivotal studies submitted as part of the registration package at the time of launch.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlighted that it is needed to reassess the relative drug effect several years after its introduction to the market. One way to ensure this would be to perform an appropriate mixed treatment comparison using all relevant RCT data when clinical development of the drug is completed, and there is likely to be less variation of drug relative efficacy and tolerability over time, or within five years after the drug launch, in most of the cases.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Llorca PM, Lançon C, Brignone M, et al. Can we well assess the relative efficacy and tolerability of a new drug versus others at the time of marketing authorization using mixed treatment comparisons? A detailed illustration with escitalopram. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015 Sep 24;3. eCollection 2015. DOI:10.3402/jmahp.v3.26776.

- Thokagevistk K, Khemiri A, Dorey J, et al. Evolution of tiotropium efficacy vs. placebo over time for the maintenance therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from investigational product to active reference. Value Health. 2015 Nov;18(7):A495. Epub 2015 Oct 20. .

- Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14:417_28.

- European Medicines Agency. Brintellix. 2013 [cited 2013 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002717/WC500159447.pdf

- Tansey MJ, Pilgrim AJ, Lloyd K. Sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine. J Neurol Sci. 1993 Jan;114(1):109–11.

- Winner P, Landy S, Richardson M, et al. Early intervention in migraine with sumatriptan tablets 50 mg versus 100 mg: a pooled analysis of data from six clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2005 Nov;27(11):1785–1794.

- Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Roon KI, et al. Triptans (serotonin, 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trials. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:633–658.

- Migraine: Developing Drugs for Acute Treatment Guidance for Industry. (2018). Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm419465.pdf

- Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, et al. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. Wiley, Chichester, U.K.; 2000. xvii+317. ISBN 0-471-49066-0.

- Thompson SG. Meta-analysis of clinical trials. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. Chichester: Wiley; 1998. p. 2570–2579.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Oct;62(10):1006–1012. Epub 2009 Jul 23.

- Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Stark SR, et al. Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007 Apr 4;297(13):1443–1454.

- Sheftell FD, Dahlof CG, Brandes JL, et al. Two replicate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of the time to onset of pain relief in the acute treatment of migraine with a fast-disintegrating/rapid-release formulation of sumatriptan tablets. Clin Ther. 2005;27(4):407–417.

- Landy S, Savani N, Shackelford S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan tablets administered during the mild-pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58(10):913–919.

- Winner P, Mannix LK, Putnam DG, et al. Pain-free results with sumatriptan taken at the first sign of migraine pain: 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(10):1214–1222.

- Hartnell NR, Wilson JP. Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the USA food and drug administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2004 Jun;24(6):743–749.

- Hoffman KB, Dimbil M, Erdman CB, et al. The Weber effect and the USA Food and Drug Administration‘s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS): analysis of sixty-two drugs approved from 2006 to 2010. Drug Saf. 2014 Apr;37(4):283–294.

- Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T, et al. Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2015 Dec;156(12):2616–2626.

AppendicesAppendix A. Systematic literature review – Search strategy

Appendix B.

List of references corresponding to relevant RCTs used in the MTC analyses of the efficacy outcome (22 publications – 25 RCTs)

Evaluation of a multiple-dose regimen of oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine. The Oral Sumatriptan International Multiple-Dose Study Group. Eur Neurol 1991; 31 [5]:306–313.

Barbanti P, Carpay JA, Kwong WJ, Ahmad F, Boswell D. Effects of a fast disintegrating/rapid release oral formulation of sumatriptan on functional ability in patients with migraine. Curr Med Res Opin 2004; 20 [12]:2021–2029.

Carpay J, Schoenen J, Ahmad F, Kinrade F, Boswell D. Efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan tablets in a fast-disintegrating, rapid-release formulation for the acute treatment of migraine: results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther 2004; 26 [2]:214–223.

Cutler N, Mushet GR, Davis R, Clements B, Whitcher L. Oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine: evaluation of three dosage strengths. Neurology 1995; 45(8 Suppl 7):S5-S9.

Dowson AJ, Massiou H, Lainez JM, Cabarrocas X. Almotriptan is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for migraine pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2002; 22 [6]:453–461.

Geraud G, Olesen J, Pfaffenrath V, Tfelt-Hansen P, Zupping R, Diener HC et al. Comparison of the efficacy of zolmitriptan and sumatriptan: issues in migraine trial design. Cephalalgia 2000; 20 [1]:30–38.

Goadsby PJ, Ferrari MD, Olesen J, Stovner LJ, Senard JM, Jackson NC et al. Eletriptan in acute migraine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison to sumatriptan. Eletriptan Steering Committee. Neurology 2000; 54 [1]:156–163.

Jelinski SE, Becker WJ, Christie SN, Ahmad FE, Pryse-Phillips W, Simpson SD. Pain-free efficacy of sumatriptan in the early treatment of migraine. Can J Neurol Sci 2006; 33 [1]:73–79.

Kaniecki R, Ruoff G, Smith T, Barrett PS, Ames MH, Byrd S et al. Prevalence of migraine and response to sumatriptan in patients self-reporting tension/stress headache. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22 [8]:1535–1544.

Landy S, Savani N, Shackelford S, Loftus J, Jones M. Efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan tablets administered during the mild-pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Int J Clin Pract 2004; 58 [10]:913–919.

Mathew NT, Schoenen J, Winner P, Muirhead N, Sikes CR. Comparative efficacy of eletriptan 40 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg. Headache 2003; 43 [3]:214–222.

Myllyla VV, Havanka H, Herrala L, Kangasniemi P, Rautakorpi I, Turkka J et al. Tolfenamic acid rapid release versus sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine: comparable effect in a double-blind, randomized, controlled, parallel-group study. Headache 1998; 38 [3]:201–207.

Nappi G, Sicuteri F, Byrne M, Roncolato M, Zerbini O. Oral sumatriptan compared with placebo in the acute treatment of migraine. J Neurol 1994; 241 [3]:138–144.

Nett R, Landy S, Shackelford S, Richardson MS, Ames M, Lener M. Pain-free efficacy after treatment with sumatriptan in the mild pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102 [4]:835–842.

Pfaffenrath V, Cunin G, Sjonell G, Prendergast S. Efficacy and safety of sumatriptan tablets (25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg) in the acute treatment of migraine: defining the optimum doses of oral sumatriptan. Headache 1998; 38 [3]:184–190.

Rederich G, Rapoport A, Cutler N, Hazelrigg R, Jamerson B. Oral sumatriptan for the long-term treatment of migraine: clinical findings. Neurology 1995; 45(8 Suppl 7):S15-S20.

Sandrini G, Farkkila M, Burgess G, Forster E, Haughie S. Eletriptan vs. sumatriptan: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple migraine attack study. Neurology 2002; 59 [8]:1210–1217.

Sheftell FD, Dahlof CG, Brandes JL, Agosti R, Jones MW, Barrett PS. Two replicate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of the time to onset of pain relief in the acute treatment of migraine with a fast-disintegrating/rapid-release formulation of sumatriptan tablets. Clin Ther 2005; 27 [4]:407–417.

Tepper SJ, Cady R, Dodick D, Freitag FG, Hutchinson SL, Twomey C et al. Oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of probable migraine: first randomized, controlled study. Headache 2006; 46 [1]:115–124.

Tfelt-Hansen P, Teall J, Rodriguez F, Giacovazzo M, Paz J, Malbecq W et al. Oral rizatriptan versus oral sumatriptan: a direct comparative study in the acute treatment of migraine. Rizatriptan 030 Study Group. Headache 1998; 38 [10]:748–755.

Visser WH, Terwindt GM, Reines SA, Jiang K, Lines CR, Ferrari MD. Rizatriptan vs. sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine. A placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Dutch/US Rizatriptan Study Group. Arch Neurol 1996; 53 [11]:1132–1137.

Winner P, Mannix LK, Putnam DG, McNeal S, Kwong J, O’Quinn S et al. Pain-free results with sumatriptan taken at the first sign of migraine pain: 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78 [10]:1214–1222.

Appendix C.

List of references corresponding to relevant RCTs used in the MTC analyses of the tolerability outcome (26 publications – 28 RCTs)

Acute treatment of migraine attacks: efficacy and safety of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, diclofenac-potassium, in comparison to oral sumatriptan and placebo. The Diclofenac-K/Sumatriptan Migraine Study Group. Cephalalgia 1999; 19 [4]:232–240.

Evaluation of a multiple-dose regimen of oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine. The Oral Sumatriptan International Multiple-Dose Study Group. Eur Neurol 1991; 31 [5]:306–313.

Sumatriptan–an oral dose-defining study. The Oral Sumatriptan Dose-Defining Study Group. Eur Neurol 1991; 31 [5]:300–305.

Carpay J, Schoenen J, Ahmad F, Kinrade F, Boswell D. Efficacy and tolerability of sumatriptan tablets in a fast-disintegrating, rapid-release formulation for the acute treatment of migraine: results of a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther 2004; 26 [2]:214–223.

Cutler N, Mushet GR, Davis R, Clements B, Whitcher L. Oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine: evaluation of three dosage strengths. Neurology 1995; 45(8 Suppl 7):S5-S9.

Dowson AJ, Massiou H, Lainez JM, Cabarrocas X. Almotriptan is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for migraine pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2002; 22 [6]:453–461.

Dowson AJ, Massiou H, Aurora SK. Managing migraine headaches experienced by patients who self-report with menstrually related migraine: a prospective, placebo-controlled study with oral sumatriptan. J Headache Pain 2005; 6 [2]:81–87.

Geraud G, Olesen J, Pfaffenrath V, Tfelt-Hansen P, Zupping R, Diener HC et al. Comparison of the efficacy of zolmitriptan and sumatriptan: issues in migraine trial design. Cephalalgia 2000; 20 [1]:30–38.

Goadsby PJ, Ferrari MD, Olesen J, Stovner LJ, Senard JM, Jackson NC et al. Eletriptan in acute migraine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison to sumatriptan. Eletriptan Steering Committee. Neurology 2000; 54 [1]:156–163.

Havanka H, Dahlof C, Pop PH, Diener HC, Winter P, Whitehouse H et al. Efficacy of naratriptan tablets in the acute treatment of migraine: a dose-ranging study. Naratriptan S2WB2004 Study Group. Clin Ther 2000; 22 [8]:970–980.

Jelinski SE, Becker WJ, Christie SN, Ahmad FE, Pryse-Phillips W, Simpson SD. Pain-free efficacy of sumatriptan in the early treatment of migraine. Can J Neurol Sci 2006; 33 [1]:73–79.

Kaniecki R, Ruoff G, Smith T, Barrett PS, Ames MH, Byrd S et al. Prevalence of migraine and response to sumatriptan in patients self-reporting tension/stress headache. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22 [8]:1535–1544.

Mathew NT, Schoenen J, Winner P, Muirhead N, Sikes CR. Comparative efficacy of eletriptan 40 mg versus sumatriptan 100 mg. Headache 2003; 43 [3]:214–222.

Myllyla VV, Havanka H, Herrala L, Kangasniemi P, Rautakorpi I, Turkka J et al. Tolfenamic acid rapid release versus sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine: comparable effect in a double-blind, randomized, controlled, parallel-group study. Headache 1998; 38 [3]:201–207.

Nappi G, Sicuteri F, Byrne M, Roncolato M, Zerbini O. Oral sumatriptan compared with placebo in the acute treatment of migraine. J Neurol 1994; 241 [3]:138–144.

Nett R, Landy S, Shackelford S, Richardson MS, Ames M, Lener M. Pain-free efficacy after treatment with sumatriptan in the mild pain phase of menstrually associated migraine. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102 [4]:835–842.

Pfaffenrath V, Cunin G, Sjonell G, Prendergast S. Efficacy and safety of sumatriptan tablets (25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg) in the acute treatment of migraine: defining the optimum doses of oral sumatriptan. Headache 1998; 38 [3]:184–190.

Pini LA, Sternieri E, Fabbri L, Zerbini O, Bamfi F. High efficacy and low frequency of headache recurrence after oral sumatriptan. The Oral Sumatriptan Italian Study Group. J Int Med Res 1995; 23 [2]:96–105.

Rederich G, Rapoport A, Cutler N, Hazelrigg R, Jamerson B. Oral sumatriptan for the long-term treatment of migraine: clinical findings. Neurology 1995; 45(8 Suppl 7):S15-S20.

Sargent J, Kirchner JR, Davis R, Kirkhart B. Oral sumatriptan is effective and well tolerated for the acute treatment of migraine: results of a multicenter study. Neurology 1995; 45(8 Suppl 7):S10-S14.

Sheftell FD, Dahlof CG, Brandes JL, Agosti R, Jones MW, Barrett PS. Two replicate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of the time to onset of pain relief in the acute treatment of migraine with a fast-disintegrating/rapid-release formulation of sumatriptan tablets. Clin Ther 2005; 27 [4]:407–417.

Tepper SJ, Cady R, Dodick D, Freitag FG, Hutchinson SL, Twomey C et al. Oral sumatriptan for the acute treatment of probable migraine: first randomized, controlled study. Headache 2006; 46 [1]:115–124.

Tfelt-Hansen P, Teall J, Rodriguez F, Giacovazzo M, Paz J, Malbecq W et al. Oral rizatriptan versus oral sumatriptan: a direct comparative study in the acute treatment of migraine. Rizatriptan 030 Study Group. Headache 1998; 38 [10]:748–755.

Tfelt-Hansen P, Henry P, Mulder LJ, Scheldewaert RG, Schoenen J, Chazot G. The effectiveness of combined oral lysine acetylsalicylate and metoclopramide compared with oral sumatriptan for migraine. Lancet 1995; 346(8980):923–926.

Visser WH, Terwindt GM, Reines SA, Jiang K, Lines CR, Ferrari MD. Rizatriptan vs. sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine. A placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Dutch/US Rizatriptan Study Group. Arch Neurol 1996; 53 [11]:1132–1137.

Winner P, Mannix LK, Putnam DG, McNeal S, Kwong J, O’Quinn S et al. Pain-free results with sumatriptan taken at the first sign of migraine pain: 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Mayo Clin Proc 2003; 78 [10]:1214–1222.