ABSTRACT

Nature-based businesses – such as those involving the land, forest, garden, or rural environment – are industries with significant growth potential. Female entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses are often invisible in statistics, as well as in research, since traditionally men have owned such companies. This had led to a lack of knowledge about the opportunities for women to start and run nature-based businesses. The aim of this paper was to explore the ambition, working conditions, and life situation for female entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses in sparsely populated areas of Sweden. Interviews were carried out with 18 female entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses in Sweden. One conclusion that was drawn from this study is that women within this industry are mainly pulled into entrepreneurship, that is, the entrepreneurship is opportunity based. Four different types of entrepreneurs were identified based on their ambitions when it comes to time spent in business and the degree of innovation. This study shows that it is often difficult to achieve profitability in a company, and the female entrepreneurs highlight that that self-employment implies hard but rewarding work. The findings of this study can be used by public actors in the design of support systems for female entrepreneurs in nature-based businesses.

Introduction

In Europe, politicians see self-employment and entrepreneurship as possible career options that offer many benefits such as autonomy and greater flexibility (European Commission, Citation2010). Since successful companies are considered to have a significant role in a country’s development, various methods are used to increase the interest in creating new businesses (Xavier, Kelley, Herrington, & Vorderwülbecke, Citation2013). Green industries are especially highlighted as particularly developable (Regeringskansliet, Citation2016). In Sweden, the term “green industry” (in Swedish “gröna näringar”) refers to economic activities in agriculture, forestry, landscape management, and other natural resource–based commercial activities in rural areas. The concept “green industry” lacks an English counterpart which is why these industries are henceforth referred to as “nature-based businesses”. The growth potential is something that policymakers have focused on as they try to support innovations in nature-based businesses through increased research and knowledge in this area. Entrepreneurs in this industry are considered to have good prospects for growth, since there is a high demand for locally produced food, renewable energy, experiences in nature, and rural tourism (Pettersson & Arora-Jonsson, Citation2009). Nature-based businesses include traditional industries such as agriculture, as well as new emerging industries that are based on nature’s resources. Examples of new industries include the processing of local food specialties (artisan food), new value creation based on forests, the development of experiences related to hunting, fishing, or other outdoor activities, and so on. These industries are core resources for business development in rural areas. Nature-based businesses can also be regarded as the backbone of many regions because they represent a high proportion of the total business community. In Sweden, there are regions where these industries employ more than a third of the region’s population (Andersson et al., Citation2014). New knowledge and innovation is crucial for the development of nature-based businesses in Sweden (Bergheden, Citation2014, 2014/15, p. 1216).

Previous research has shown that women as entrepreneurs in nature-based businesses are invisible in terms of statistics, as well as in research about women’s entrepreneurship, since women are often not listed as the owner of such companies (Pini, Citation2004). Haugen (Citation1985) states that women in nature-based business have difficulties in identifying their work, often seeing work on farms as not work at all. Women see the label “farmer” as one that is used by men. Women also attach very little value to their own work on the farm, as they do not see it as real work (Whatmore, Citation1991). In a study in the Netherlands, Bock (Citation2004) showed that men see it as negative if they are not the breadwinner. Hence, if women start their own company, it is not seen as a good thing, and therefore it might be better to be invisible entrepreneurs. This has resulted in poor knowledge about women’s entrepreneurship in nature-based businesses. Furthermore, in Sweden, as in most other countries around the world, women are underrepresented in terms of starting and running businesses (Kelley, Singer, & Herrington, Citation2016). Sweden is often portrayed as a gender-equal country compared with other countries, and the employment rate is fairly equal between the sexes (Statistics Sweden, Citation2014). However, when it comes to entrepreneurship, men start up almost twice as many companies as women do (Growth Analysis, Citation2016). Previous studies have also shown that women prefer to be employed (Equal Opportunities Policy Commission, SOU 2005, p. 66). One reason for this could be that many women are still the ones caring for the family while also trying to have career. According to a time-use survey conducted in Sweden, women spend significantly more time on household chores compared with men, since they often have prime responsibility for the household (SCB, Citation2012). However, this fact may also result in the reverse behaviour, since previous research has shown that women in particular are motivated to start their own company due to the opportunity it affords to create a more balanced lifestyle (Hughes, Citation2006). Furthermore, this is a gender issue, since “work–family factors are far less salient for men” (Hughes, Citation2006, p. 113). It is problematic if women are expected to create their own livelihood at the same time as being responsible for childcare (see Ahl, Citation2004). In addition, a recent study shows that self-employed individuals, in particular self-employed women, perceive greater time costraints (i.e. too much too do) than employees do (Hagqvist, Toivanen, & Vinberg, Citation2015).

A major reason for women to choose self-employment is that they are driven by the opportunity to be flexible and to be able to use their time in their own way (Still & Timms, Citation2000). In nature-based businesses, it is well-known that women’s work is often closely intertwined with their family life, since they often live and work at the same place. Quite often, they need to integrate their businesses with their identity as a parent (Caballé, Citation1999; Sattler Weber, Citation2007). Previous research from Nordenmark, Vinberg, and Strandh (Citation2012) highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between working conditions, work–life balance, and well-being among self-employed individuals. This is because improving the well-being of self-employed people may result in an increase in the number of such companies, which in turn could be positive for the region and its development. Dodge, Daly, Huyton, and Sanders (Citation2012) have argued that there is a challenge in defining well-being. “Well-being is more than just happiness. As well as feeling satisfied and happy, well-being means developing as a person, being fulfilled, and making a contribution to the community” (Shah & Marks, Citation2004, p. 2). Recent research states that well-being is the ability to fulfil goals, happiness, and life satisfaction (Dodge et al., Citation2012). For female entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses, it is interesting to study their perception on well-being, since one study has shown that farmers’ well-being is poorer compared with salary earners (Saarni, Saarni, & Saarni, Citation2008).

Motivation and driving forces to be self-employed

Previous research has shown that the motivation for entrepreneurship has a vital role in the creation of new companies and that this is an important consideration when studying the underlying causes of entrepreneurship (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011; Segal, Borgia, & Schoenfeld, Citation2005; Shane, Locke, & Collins, Citation2003). Theories about what motivates individuals to start and run businesses are extensive, but the two perspectives that have emerged from empirical research are usually called “push” and “pull” (Brockhaus, Citation1980; Gilad & Levine, Citation1986). When there are attractive and potentially profitable business opportunities, individuals will be attracted or pulled to entrepreneurial activities (Gilad & Levine, Citation1986). The underlying motivation can also be about developing a strong interest or a desire to be independent (Kirkwood, Citation2009). Within this theory, earlier experiences of entrepreneurship, for example from parents’ entrepreneurship, are raised as important underlying factors for wanting to start a business (Gilad & Levine, Citation1986). Proponents of the second motivation track say instead that individuals are forced or pushed into entrepreneurship for negative reasons (Gilad & Levine, Citation1986). Dissatisfaction with existing employment, unemployment (Brockhaus, Citation1980), or career setbacks (Gilad & Levine, Citation1986) are examples of push factors. Instead of push-and-pull entrepreneurship, Reynolds, Camp, Bygrave, Autio, and Hay (Citation2001) use the terms “opportunity-driven” and “necessity-driven” entrepreneurship to describe the underlying drivers of entrepreneurial activities. Schumpeter (Citation1934, p. 93) argues that the entrepreneur is motivated by “the joy of creating” which reflects a more passionate way to explain entrepreneurship. This is something that also is highlighted in recent research by Cardon, Wincent, Singh, and Drnovsek (Citation2009). Passion nowadays is considered to be one of the most observed phenomena in the entrepreneurial process (Smilor, Citation1997). Current research shows that the passion of founder companies has a significant impact on creativity, endurance, and efficiency. Furthermore, passion is considered to form the basis for developing the business concept and also promotes the ability to mobilise resources and establish contacts, and that is the reason why passion is also considered to have a positive impact in terms of managing the different roles that entrepreneurship requires (Baum & Locke, Citation2004; Cardon et al., Citation2009). Minniti and Nardone (Citation2007, p. 236) argue that there may be “an inherent difference in the propensity to start a business across genders, and that such differences have primarily perceptual causes are universal, and do not result from socio-economic and contextual circumstances”. Following on from this line of reasoning, the present study investigated the underlying drivers of entrepreneurship among businesswomen within nature-based businesses.

Prerequisites for female entrepreneurship in general and within nature-based businesses in particular

Entrepreneurship is essential for the prosperity of a country, and therefore there is a constant need to create favorable and equal business conditions for men and women (Lundström & Stevenson, Citation2005). Although women run companies to a lesser degree than men do, their entrepreneurship makes a significant contribution to the welfare of society, both as innovators and as employers (Brush, Carter, Gatewood, Greene, & Hart, Citation2006). Previous research shows, however, that the prerequisites for women and men to start and run their own businesses are unequal, and a critical reason for this is related to the unfair distribution of public funds (see, e.g., Marlow & Patton, Citation2005; Nutek, Citation2007). Despite increased awareness of the problem, few changes have occurred in recent decades (Coleman & Robb, Citation2014).

The effort to increase women’s entrepreneurship is an ongoing process, and in recent years, the focus has been directed towards women’s entrepreneurship within nature-based businesses (Equality Academy, Citation2009). Increased entrepreneurship by women within nature-based businesses is particularly important, since these activities are carried out in the context characterised by rural and sparsely populated areas, and also because they create a base for other industries (Bexelius, Citation2010). In today’s society, traditional farming is being abandoned daily, and it is therefore important to find new ways to take advantage of the land area that otherwise will be lost as a business opportunity. The conditions for creating a livelihood within this industry are, however, often challenging. Recent research shows that for financial reasons, there is an increasing and common need to combine self-employment with so-called off-farm employment (Beach & Kulcsár, Citation2016).

Above all, the existing support system tries to achieve increasing innovation in the green industry, which has resulted for example in a number of new advisers that work with innovations in nature-based businesses (Klerkx & Gildemachter, Citation2012). According to Cooke et al. (Citation2011), innovation as a competitive strategy has never been more important than it is today. Martin and Trippl (Citation2014) emphasise, however, the importance of a holistic approach and highlight that regional innovation policy must take into account the context and the peculiarities of the region when providing funding. It might be problematic to find an innovation system that has a “one-size-fits-all” policy (Nauwelaers, Citation2011; Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2011). If society generally asks for more women within nature-based businesses, a good place to start might be to increase the knowledge about these entrepreneurs. What are the underlying reasons that motivate women to run nature-based businesses which are traditionally regarded as male dominated? Knowledge is lacking regarding female entrepreneurs’ motivations and ambitions, but also about the prevailing conditions such as well-being and working conditions, as well as problems and barriers which these businesswomen face in their everyday lives (McGhee, Kyungmi, & Jennings, Citation2007).

Aim and research questions

The aim with this paper was to explore the ambition, working conditions, and life situation of female entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses in sparsely populated areas of Sweden. This was done by analysing the following research questions:

RQ1:

What is the main reason why female entrepreneurs start their own nature-based business?

RQ2:

Are there discernable patterns of ambition that could contribute to understanding female entrepreneurship within nature-based businesses?

RQ3:

How do the working conditions in nature-based businesses influence women’s perception of their work–life balance and well-being?

Method

The study took place in a sparsely populated county located in the middle of Sweden. In terms of area, the county represents 12% of the land area in Sweden, but only 1.4% of the country’s population lives there. This makes the county one of the most sparsely populated regions in both Sweden and the European Union. The county is rich in fresh air, clean water, and vast mountains, marshes, and forests, which provide good conditions for, among other things, outdoor tourism, mountain fishing, and reindeer herding (Jämtland County Administrative Board, Citation2012). Over the past 50 years, the county has had negative population growth mainly due to a lack of large industries (Sahlberg, Citation2000). Entrepreneurship in the county is slightly higher than the average in Sweden at 13.1/1000 inhabitants (Sweden 11.6/1000). Female entrepreneurs account for 34% of new businesses. Most companies are small and are sole traders (Growth Analysis, Citation2016).

The data for this study were collected between September 2015 and April 2016. The research design was constructed as a qualitative explorative study on female entrepreneurs in various nature-based businesses. Their businesses covered a wide range of products and services, including food, refinement, green care, and nature-based tourism. Data were collected through 18 semi-structured interviews, with a focus on female entrepreneurs’ motivations for starting their businesses, growth ambitions, working conditions, and well-being. The 18 women were between 25 and 60 years of age, and all agreed to be interviewed. Around half had had their business for five years or less, whereas the other half had been businesswomen for at least 10 years. The interviews lasted one to two hours and followed a questionnaire with semi-structured questions. The interview guide covered various questions about motivation and well-being, such as “What was the main reason why you started your business?”; “To what degree do you want the company to evolve?”; “What impact does the business have on your health and well-being?”. The interviews were recorded, and speaker notes and observations were made during the conversation. The data were divided into different categories and variables and then analysed with an interpretive approach.

Study results and analytical analyses

The intention of the first research question was to gain a better understanding of what motivates women to start their own business in the nature-based industry. Previous research highlights that the motivation for entrepreneurship has a vital role in the inception of new businesses, and it is therefore an important area to study in order to stimulate increased self-employment (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011; Segal et al., Citation2005; Shane et al., Citation2003). Although different factors such a country’s economic development and culture are important for understanding the creation of new companies (Reynolds, Citation2011), previous research shows that individual factors such as motivation and confidence appear to have the greatest impact on the complex decision to start new businesses (Minniti & Nardone, Citation2007).

The majority of the businesswomen in this study own and operate their businesses themselves and have done so for a long time, often for more than 10 years. One of the main reasons why they started their own business is independence, as well as a keen interest in what they are doing. The women expressed a strong desire to “decide yourself”, “own power”, and “take control over my life”. They also highlighted the importance of doing what they wanted to do based on a significant interest in nature and animals. These are all examples of pull factors, that is, the reason for starting a company is due to various opportunities that the women associated with being self-employed. There were also those who expressed other opportunities for doing business, such as “making money”, “saw a need”, and “create jobs for others”, and these are also examples of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. For some of the female entrepreneurs, however, the self-employment had been a necessity: “there are no jobs available in this industry” or “I wanted to live and work in the resort … this solution was the only way to do that”. They saw themselves as forced, or pushed, to start their own business, as there were no other options. A further reason why some had started their own company had to do with dissatisfaction with their previous work situation: “there is no thrill to be employed” or “I was fed up being an employee, and it’s fun to try something new”. These are examples of a combination of pull and push factors, since the change in their working situation resulted in something positive. In line with previous research, there are various reasons why women start and run their own business.

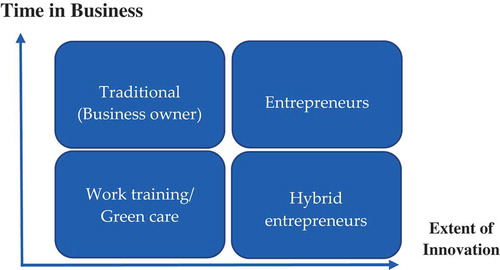

The second research questions explored whether there are discernable patterns of ambition that could contribute to understanding female entrepreneurship within nature-based businesses. In order to answer this question, the women were asked to describe their businesses. The interpretation of this question developed, after several iterations, a pattern in which four different business types could be discerned (see ). Some of the women considered their business activities to be a hobby, whereas others were very interested in being innovative. Some of the female entrepreneurs wanted to focus on the core “product” or “service”, and they were not interested in dealing with “new” products or services on their farms. Other women had many new ideas but were lacking the resources to fulfil them. Many of the women interviewed could not make enough money from their company, so they combined it with employment. Based on the different narratives from the female entrepreneurs, two different perspectives were identified: time in business and extent of innovations. The following model of different types of female entrepreneurs was prepared.

The first category is referred to as the “traditional”. These female entrepreneurs ran a conventional agriculture farm with the aim of producing raw materials such as high-quality meat. These women did not see themselves as innovators. Instead, they based their business on traditional methods inherited from generation to generation.

The second category of entrepreneurs is called “working training/green care”, as these women were actually outside for their working life and had animals for rehabilitative purposes. Often, they ran their business indirectly, that is, their partner was the company owner, while they worked in the shadows. Similar to the first category, they handled their business in a traditional way.

The third group of women are defined as “hybrid entrepreneurs”. These entrepreneurs did not have the business as their main income. Instead, they combined it with another job. Many of these entrepreneurs showed great capacity for innovation, but they were limited mainly by time, since they did not engage in the business on a full-time basis.

The fourth category of women are the “entrepreneurs”. These women ran their business in an innovative and groundbreaking way. The traditional business had been supplemented with various core areas such as “farm living”, “nature-based tourism”, and so on, and the aim of the business was to create a good living both financially and socially.

These results indicate that the support system in Sweden, which almost exclusively is targeted at innovative entrepreneurs (Martin & Trippl, Citation2014), will apply only to a minority of the entrepreneurs within nature-based businesses.

Another finding, based on these four types, is that self-employed women who are considered as “entrepreneurs” are motivated to start their own business primarily out of a desire for independence. Unequivocally, these women do what they want to do. They have a high degree of innovation, and they work full time or more in their company. A common denominator for the hybrid entrepreneurs is that a huge interest in what they do has motivated them to be hybrid entrepreneurs, but they also expressed concerns about the economy, which constitutes the main reason why they have another job in addition to their own company. This is in line with the result from Beach and Kulcsár (Citation2016) who argue that work off-farm is often due to financial need.

The women in the business type identified as traditional also work full time or more in their company. The difference between them and the entrepreneurs is that the traditional owners want to work in the core business. Some of these business owners have become entrepreneurs because there were no other options. The last type of entrepreneurs – “the work training entrepreneurs” – are largely invisible as entrepreneurs. They do not own the company themselves because of ill health. Instead, their partner is the business owner. The women run and take care of the company and also take responsibility for the animals. Their primary purpose is to return to working life and to improve their well-being. They want to live on the income from the company, but they are not able to do so.

Since some of the entrepreneurs have become self-employed due to a lack of other options, an important question is how the origin to the situation affects their health and well-being, which brings us to the last research question in this study.

The women were asked to consider four statements in order to analyse in what way their self-employment affected their health and well-being: “The company makes me feel good; this is what I want to work with”; “The company makes me feel good, but it’s not what I want to work with”; “I probably felt better as an employee”; and “I’d rather be an employee”.

The results show that only one women would prefer to be an employee. The rest of them preferred to be self-employed, and they did not think that their well-being would have been better if they had been employed, despite the fact that the working conditions within the sector did not seem to be the best. The majority of the female entrepreneurs report a poor physical environment in terms of air and light; long days with a lot of work that is often risky, and ever-present economic responsibility. Nonetheless, it seems that the benefits outweigh these, and the entrepreneurs highlight the the possibilities of combining the company with their hobby and family life. They decide their work and the pace of the work themselves. Some of the women argue that there is no stress, since “you live the life you want”. This attitude is not shared by all, as many women also highlight the stress that is caused by being responsible for their own income, which is in line with results of Beach and Kulcsár (Citation2016). Another finding during the interviews was that entrepreneurship in nature-based businesses provides an opportunity to socialise within the family if the partner is also involved in the activity, and “the children hang on”. It was important to be able to combine family life with the company, since they spend a lot of time in their company, or as one woman described it, “there is an inherent risk of working too much”.

The commonly characteristic for the businesswomen was that they reported a high level of well-being as entrepreneurs. As mentioned before, well-being is taken to mean the things that make people grow as a person, such as personal development or a sense of contributing to society. The women expressed these concepts with statements such “I feel like I make a difference” or “it feels good to create jobs for other villagers”. There were also those who highlighted the possibilities for personal development that the self-employment entailed.

Discussion and conclusions

In Sweden, as well as in a large part of the rest of the world, abandonment of traditional farming is a daily problem, and it is therefore important to find new ways for livelihoods to continue in these areas. Since entrepreneurship is considered as one of the main driving forces in a country, various methods are used in order to increase the interest in creating new businesses in general and in rural areas in particular. Growth opportunities in nature-based businesses are deemed to be very satisfactory. It is therefore considered important to provide the best possible conditions for those men and women who want to start and run businesses in these areas. The focus of this paper was female entrepreneurs, since previous knowledge about women in this industry is limited.

The results of the study show that female entrepreneurs in nature-based businesses are mainly driven by a great interest in nature and wildlife, and that they share basic values about what is important in life in general. There is a desire from these female entrepreneurs to combine their job with what they are passionate about. This was a common feature of all the interviewed women. This means that they have chosen to become self-employed mainly from a pull-driven perspective, that is, they saw the opportunities for this. Some of the women were outside the labor market due to poor health and saw employment in the industry mainly as a means of rehabilitation by running a small (hobby) business as farmers. Although they could not earn a living from their company, and despite the fact that they had no other options, they regarded their company as a way back, that is, an opportunity-driven occupation.

The results also show major differences when it comes to the ambition with the company and how the female entrepreneurs run their businesses. Some of the women consider their business activities as a hobby, whereas others are very interested in innovation. Conversely, some of the female entrepreneurs want to focus on the core “product” or “service”, and they are not interested in creating “new” products or services on their farm. There are other women who have a lot of new ideas but are lacking the resources to fulfil them. Many of the women interviewed do not make enough money from their company, and so they combine it with employment.

Another problem identified in the companies is related to time. Self-employment within nature based-businesses involves long working days, albeit with tasks that the women mainly chose themselves. However, only one of the entrepreneurs said that she would rather be employed. This entrepreneur was a hybrid entrepreneur and worked largely full-time as an employee. She meant that her company had not affected her well-being in a positive way, as she never had enough time to finish her tasks.

Although most women described a work situation that involved long hours of hard work, they felt good and this was what they wanted to do. This is strongly linked with the obvious interest that had motivated the women to become self-employed in this area. They run their businesses, often in rural regions, and their work is meaningful to them.

Implications

Creating innovative environments is essential in order to ensure innovation and competitiveness in small business. This is also something that today’s support systems aim to do, that is, to create a hotbed in order to increase innovation in the natural resource–based industry, since this business area is considered to have great potential for development as well as possibilities to create full-time employment. However, the results of this study show that not all business owners want to be innovative. Some just want to grow within the traditional business that they operate, and some just want to be able to feed themselves and feel well. Yet, all businesses, regardless of their growth ambition, contribute to more sustainable development of rural society – and this is something that the support system should understand more about, since they only target support schemes at innovative businesses and start-ups.

The female entrepreneurs in this study are not asking for support, but rather conditions that would enable them to make a living from their company. Previous research shows that nowadays it is difficult to earn a living in this industry, and often at least one member of the family is forced to take other employment away from the farm. By being aware of women’s working conditions in this industry and that entrepreneurs often have to combine family life with their business life, public actors should create better conditions that would have a positive impact on the companies’ ability to survive. The majority of the entrepreneurs expressed concerns about the economy and what would happen to the company if they became sick.

All entrepreneurs contribute to a region’s development, since they live and work in the locality, which in turn also generates work for others in the region. The support system needs not only to target businesses that are innovative but also to maintain existing businesses. This is important to keep in mind when support systems for entrepreneurs in nature-based businesses are designed. It seems to be problematic to find an innovation system that has a “one-size-fits-all” policy that can be adopted by all women and their different nature-based businesses. This finding is similar to that of previous studies by Tödtling and Trippl (Citation2011) and Nauwelaers (Citation2011). In line with Martin and Trippl (Citation2014), regional innovation policies must adopt a holistic approach where the peculiarities and capacities of the region are taken into account.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahl, H. (2004). Företagandets särskilda nytta, i. In D. Ericsson (Ed.), Det oavsedda entreprenörskapet (pp. 31–39). Lund: Academia Adacta.

- Andersson, K., Eidenvall, L., Lindgren, M., Lindén, D., Molander, R., & Wennerström, C. (2014). Innovation i de gröna näringarna [Innovation in the nature-based businesses]. Stockholm: Kairos future.

- Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587–598. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.587

- Beach, S. S., & Kulcsár, L. J. (2016). It often takes two income earners to raise a farm: On-farm and Off-farm employment in Kansas. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 10, 4.

- Bergheden, S. (2014). Motion 2014/15:1216, [Nature-based businesses in the future]. Retrieved February 5, 2016, from https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/motion/framtidens-grona-naringar_H2021216

- Bexelius, E. (2010). Hästen i Sverige – betyder mer än du tror [The horse in Sweden- More important than you think]. Stockholm: Nationella Stiftelsen för Hästhållningens Främjande.

- Bock, B. B. (2004). Fitting in and multi-tasking: dutch farm women's strategies in rural entrepreneurship. 44(3), 245-260. doi:10.1016/S0362-3319(00)00111-7

- Brockhaus, R. H. (1980). The effect of job dissatisfaction on the decision to start a business. Journal of Small Business Management, 18(1), 37–43.

- Brush, C. G., Carter, N. M., Gatewood, E. J., Greene, P. G., & Hart, M. M. (2006). Introduction: The Diana project international. In C. G. Brush, N. M. Carter, E. J. Gatewood, P. G. Greene, & M. M. Hart (Eds.), Growth oriented women entrepreneurs and their businesses: A global research perspective (pp. 3–22). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Caballé, A. (1999). Farm tourism in Spain: A gender perspective. GeoJournal, 48, s. 245–252. doi:10.1023/A:1007044128883

- Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511–532. doi:10.5465/AMR.2009.40633190

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. doi:10.1111/jsbm.2011.49.issue-1

- Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2014). Financing high-growth women-owned enterprises: Evidence from the United States. Washington, DC: The National Women’s Business Council.

- Cooke, P., Asheim, B. T., Boschma, R., Martin, R., Schwartz, D., & Tödtling, F. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of regional innovation and growth. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2, 3. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

- Equality Academy. (2009). Den osynliga entreprenören [the invisible entrepreneur]. Genus och företagande i de gröna näringarna [Gender and entrepreneurship in the nature based businesses]. Retrieved from https://www.lrf.se/om-lrf/uppdrag-vision-och-vardegrund/jamstalldhet/jamstalldhetsakademin/debatt--forskning/.

- Equal Opportunities Policy Commission, SOU 2005:66. Retrieved from http://www.regeringen.se/49bb92/contentassets/b46b81ff8ea142fcb535f70d3919d696/makt-att-forma-samhallet-och-sitt-eget-liv-missiv-och-kapitel-1-5-del-1-av-4-sou-200566.

- European Commission. (2010). European employment observatory review - Self-employment in Europe 2010. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Gilad, B., & Levine, P. (1986). A behavioral model of entrepreneurial supply. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(4), 45–54.

- Growth Analysis. (2016). Nystartade företag i Sverige 2015, [New enterprises in Sweden 2015]. Retrieved September 9, 2016, from http://www.tillvaxtanalys.se/publikationer/statistikserien/statistikserien/2016-10-03-nystartade-foretag-i-sverige-2015.html

- Hagqvist, E., Toivanen, S., & Vinberg, S. (2015). Time strain among employed and self-employed women and men in Sweden. Society, Health & Vulnerability, 6. doi:10.3402/shv.v6.29183

- Haugen, M. (1985). Bondekvinners arbeid og helse [Female farmers work and health] (Report no.5/87). Trondheim: Centre for Rural Research.

- Hughes, K. D. (2006). Exploring motivation and success among Canadian women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 19(2), 107–120. doi:10.1080/08276331.2006.10593362

- Jämtland County Administrative Board. (2012). Genomförandestrategi för Landsbygdsprogrammet 2007-2013 i Jämtlands län [online]. Retrieved September 5, 2016, from http://www.lansstyrelsen.se/jamtland/SiteCollectionDocuments/Sv/lantbruk-och-landsbygd/landsbygdsutveckling/Genomforandestrategi-2012-02-13-beslut-2.pdf

- Kelley, D. J., Singer, S., & Herrington, M. (2016). The global entrepreneurship monitor 2015/2016 (Global Report). Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. Retrieved from http://thecis.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GEM-Global-Report-2015.pdf.

- Kirkwood, J. (2009). Is a lack of self-confidence hindering women entrepreneurs? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(2), 118–133. doi:10.1108/17566260910969670

- Klerkx, L., & Gildemachter, P. (2012). The role of innovation brokers in agricultural innovation systems. In The World Bank (Ed.), Agricultural innovation systems: An investment sourcebook. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Lundström, A., & Stevenson, L. A. (2005). Entrepreneurship policy; theory and practice. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Marlow, S., & Patton, D. (2005). All credit to men? Entrepreneurship, finance and gender. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 29(6), 717–735. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1540-6520

- Martin, R., & Trippl, M. (2014). System failures, knowledge bases and regional innovation policies. The Planning Review, 50(1), 24–32. doi:10.1080/02513625.2014.926722

- McGhee, N., Kyungmi, K., & Jennings, G. (2007). Gender and motivation for agritourism entrepreneurship. Tourism Management, 28, s. 280–289. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2005.12.022

- Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else’s shoes: The role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(1), 223–238. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9017-y

- Nauwelaers, C. (2011). Intermediaries in regional innovation systems: role and challenges for policy. In Cooke, P., Asheim, B., Boschma, R., Martin, R., Schwartz, D., & Tödtling, F. (Eds.). Handbook of regional innovation and growth (pp. 467–481). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Nordenmark, M., Vinberg, S., & Strandh, M. (2012). Job control and demands, work-life balance and wellbeing among selfemployed men and women in Europe. Society, Health & Vulnerability, 3(1). Retrieved from http://miun.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:570373/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Nutek. (2007). Utfall och styrning av statliga insatser för kapitalförsörjning ur ett könsperspektiv [Outcome and management of government initiatives for raising capital from a gender perspective] (Nutek R 2007:34). Stockholm: NUTEK.

- Pettersson, K., & Arora-Jonsson, S. (2009). Den osynliga entreprenören - Genus och företagande i de gröna näringarna. LRF, Jämställdhetsakademi [The invisible entrepreneur - Gender and entrepreneurship in the nature-based businesses]. Stockholm: LRF.

- Pini, B. (2004). Counting them in, not out: Surveying farm women about agricultural leadership. Australian Geographical Studies, 42(2), s. 249–259. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8470.2004.00262.x

- Regeringskansliet. (2016). Mål för areella näringar, landsbygd och livsmedel. Retrieved from http://www.regeringen.se/regeringens-politik/areella-naringar-landsbygd-och-livsmedel/mal-for-areella-naringar-landsbygd-och-livsmedel/

- Reynolds, P. D. (2011). New firm creation: A global assessment of national, contextual, and individual factors. Hanover: Now Publishers.

- Reynolds, P. D., Camp, S. M., Bygrave, W. D., Autio, E., & Hay, M. (2001). The global entrepreneurship monitor 2011 Executive Report, GEM 2011. Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

- Saarni, S. I., Saarni, E. S., & Saarni, H. (2008). Quality of life, work ability, and self employment: A population survey of entrepreneurs, farmers, and salary earners. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 65(2), 98–103.

- Sahlberg, L. (2000). Värsta avfolkningen i Jämtland. Integrationsverkets rapporter 2000-1999[Worst depopulation in Jämtland. Integration Board Reports 2000-1999]. Retrieved from http://www.mkc.Botkyrka.se/biblioteket/Publikationer/hemortskap7.pdf

- Sattler Weber, S. (2007). Saving St James: A case study of farmwomen entrepreneurs. Agriculture and Human Values, 24, s. 425–434. doi:10.1007/s10460-007-9091-z

- SCB. (2012). Nu för tiden - En undersökning om svenska folkets tidsanvändning år 2010/11. Levnadsförhållanden [These days - A study of Swedish people’s time use in 2010/11. Living conditions.] Rapport 123. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hittastatistik/Publiceringskalender/Visa-detaljerad-information/?PublObjId=18561

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 11(1), 42–57. doi:10.1108/13552550510580834

- Shah, H., & Marks, N. (2004). A well-being manifesto for a flourishing society. London: The New Economics Foundation.

- Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

- Smilor, R. W. (1997). Entrepreneurship: Reflections on a subversive activity. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(5), 341–346. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00008-6

- Statistics Sweden. (2014). Women and men in Sweden 2014: Facts and figures. Örebro, Sweden: Statistics Sweden, Population Statistics Unit.

- Still, L. V., & Timms, W. (2000). Women’s business: The flexible alternative workstyle for women. Women in Management Review, 15(5/6), 272–282. doi:10.1108/09649420010372931

- Tödtling, F, & Trippl, M. (2011). Regional innovation systems.In Cooke, P., Asheim, B., Boschma, R., Martin, R., Schwartz, D., & Tödtling, F. (Eds.). (Handbook of regional innovation and growth (pp. 455-466). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Whatmore, S. (1991). Life cycle or patriarchy? Gender divisions in family farming. Journal of Rural Studies, 7(1–2), 71–76. doi:10.1016/0743-0167(91)90043-R

- Xavier, S. R., Kelley, D., Herrington, M., & Vorderwülbecke, A. (2013). The global entrepreneurship monitor, 2012 Global Report, GEM 2012. Retrieved from http://www.gemconsortium.org/report/48545.