ABSTRACT

In this article, it is argued that improving work sustainability is of the utmost importance if we want to keep an older labour force (healthy) at work. It is argued that making gains in the sustainability of work is – first and foremost – a matter of improving job quality at the bottom of the labour market. This is demonstrated using two cases characterized by working conditions that have important impacts on health and well-being: job strain and precarious employment.

Background

In the past decade, almost all European countries have implemented policy measures aimed at prolonging individuals’ working careers. These measures have consisted of delaying the legal retirement age, discouraging early exit from the labour force, and creating incentives for workers to remain employed until a later age. These reforms are intended to increase employment rates, especially in older age groups.

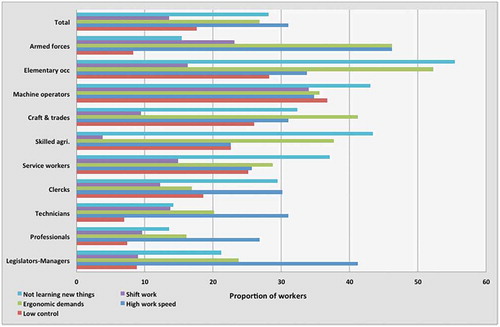

Figure 1. Distribution of the prevalence of selected working conditions over occupational categories (Belgium, 2010). Own calculations; Data: EUROFOUND, European Working Conditions Survey, 2010 (https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-working-conditions-surveys), Belgium.

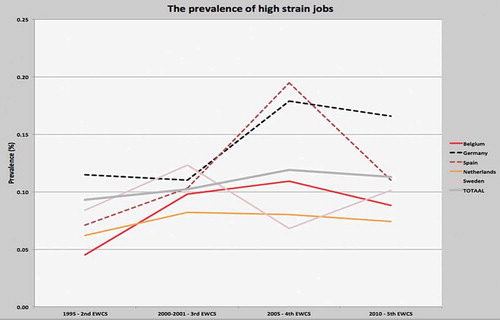

Figure 2. The prevalence of job strain in a selection of European countries (EWCS, 1995–2010).Own calculations; Data: EUROFOUND, European Working Conditions Surveys, 1995, 2000, 2005, and 2010 (https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-working-conditions-surveys).

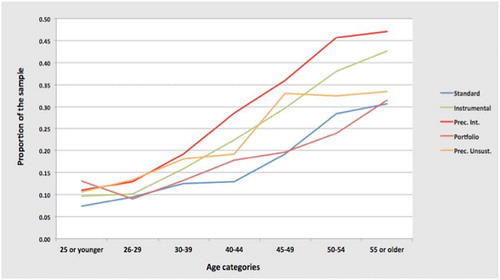

Figure 3. The age-stratified distribution of the association between the prevalence of general self-perceived health and employment types. Source: Malmusi (Citation2015).

Such reforms are justified because populations generally show an increasing life expectancy and improved health. Life expectancy at the age of 50 has increased in most Western countries. Between 1960 and 2006, both Belgium (30 years in 2005) and Sweden (32 years in 2005) added an average of five years in life expectancy (Glei, Meslé, & Vallin, Citation2010). However, when looking at “healthy life expectancy”, the increase is smaller. Healthy life expectancy at 50 years of age is still below 20 years on average in most European countries, meaning that many people start to experience chronic illnesses in their mid-sixties. The older (and sicker) age composition of the labour force is one of the main drivers behind important increases in disability benefit claims in most European countries (OECD, Citation2013). However, the higher selectivity of other income-replacement schemes, combined with important changes in the world of work that affect work intensity and job quality, should also be seen as causes of increasing disability and hampered possibilities of working until a later age (OECD, Citation2009).

How sustainable are jobs for older workers?

A first question concerns the specific meaning of “sustainable work”. An interesting conceptual framework is offered by the Finnish Occupational Health Institute, which uses the concept of “workability” (Ilmarinen, Gould, Järvikoski, & Järvisalo, Citation2008). Workability is a multilayered concept; it stresses the importance of aligning workers’ health and functional capabilities, competences, values and motivation, and job characteristics. In other words, a sustainable job is a job that suits the capabilities and motivations of the worker. These capabilities and motivations may depend on personal factors such as health, cognition, and age, but they are also heavily dependent on the social context. A person’s functioning at work cannot be conceived separately from his/her household situation and other extra work life domains. The definition of sustainable work that was developed by Vendramin et al. (Citation2012) for EUROFOUND also echoes the “workability approach”. According to Vendramin et al. (Citation2012), sustainable work exhibits three important characteristics: (1) ‘‘biocompatibility”, which means that the work is adapted to the functional properties of the human organism and to its evolution with age; (2) “ergo-compatibility”, where efficient work strategies are developed; and (3) “socio-compatibility”, which allows self-fulfilment in the familial and social areas, and the “possibility of controlling one’s life course.” (Vendramin et al., Citation2012).

In an interesting report, Vendramin et al. (Citation2012) used data from the 2010 Working Conditions Survey of EUROFOUND to investigate the working conditions of older and younger European workers. Based on the prevalence of different working conditions among different age groups, it is possible to determine what a sustainable job for older workers should look like (and what it should definitely not look like). Compared to younger workers, older workers tend to be employed in jobs with lower physical and quantitative workloads, reduced working hours and flexibility, fewer “socially unfriendly work hours” (e.g. night and shift work), and higher skill discretion and autonomy (Vendramin et al., Citation2012). Ideally, they should also be employed in jobs that offer ample learning opportunities and be able to adapt their work to their changing capabilities. In the current European labour market, this is probably the most problematic issue because learning opportunities strongly decrease with workers’ age (Vendramin et al., Citation2012).

Inequality: the elephant in the room

Comparative analyses of the evolution of cross-country differences in job quality often ignore distribution of job quality along the socio-economic ladder. Nevertheless, it could be argued that increasing polarization between “good” and “bad” jobs (Goos, Manning, & Salomons, Citation2009) is one of the most important problems to address in discussions of sustainable work. The health inequality correlates of working conditions are among the first and most consistent sets of findings in epidemiology (Marmot, Citation2001). Mortality registry data show important differences among occupations in terms of standardized mortality rates and (healthy) life expectancy, with professionals and managerial workers being far better off than blue-collar and lower-skilled service workers (Deboorsere & Gadeyne, Citation2009; Van Oyen, Deboosere, Lorant, & Charafeddine, Citation2011). Among older European wage-earners, important differences in general self-perceived health are observed among occupational groups (Vendramin et al., Citation2012). At the same time, a similar structure of inequality can be observed for job characteristics, such as ergonomic demands, low control, or shift work (see ). Moreover, the relationship between adverse working conditions and decreased health and life expectancy is well-established (Hoven & Siegrist, Citation2013; Landsbergis, Grzywacz, & Lamontagne, Citation2014).

There is evidence that current changes in the labour market are leading to sharper divisions between “good” and “bad” jobs in terms of health-related characteristics (Hurley, Fernandez-Macias, Munoz de Bustillo, & Al., 2015). The degradation of “protected employment” under the so-called “standard employment relationship” into a system of “flexible accumulation” (Vallas, Citation1999) has led to the growth of well-rewarded work with higher autonomy and task discretion at the top of the labour market, while at the same time less rewarded, less socially protected, insecure, and poor jobs at the bottom of the labour market also grew in number (Julia, Vanroelen, Van Aerden, Bosmans, & Benach, in press). Therefore, the potentially adverse impact of “the changing world of work” on health inequality can be seen as a prominent issue for the research agenda of the future (Burdorf, Citation2015). The urgency of this need for awareness can be demonstrated by documenting the evolution and health impact of two risk factors for the 21st-century working population: job strain and precarious employment.

Job strain and precarious employment: two indicators of the health impact of labour market polarization

The case of job strain

Job strain (Karasek, Citation1979) is one of the best-documented work-related psychosocial risk factors. The combination of low control over the work environment (low autonomy and low skill discretion) and high (quantitative) job demands – especially in combination with low social support at work – has been shown to be related to a number of adverse health outcomes, including poor mental health, fatigue, musculoskeletal complaints, cardiovascular disease, and mortality (Hauke, Flintrop, Brun, & Rugulies, Citation2011; Häusser, Mojzisch, Niesel, & Schulz-Hardt, Citation2010; Landsbergis, Dobson, Koutsouras, & Schnall, Citation2013).

Job strain is widely distributed over the occupational spectrum, although it is more common in lower-skilled, routinized occupations that have been affected by processes leading to work intensification, such as organizational changes, mechanization, and outsourcing. Therefore, job strain is more common among lower-skilled workers and workers at the lowest echelons of bureaucratic organizations (e.g. workers without managerial authority; Vanroelen, Citation2009).

Job strain is thus not exclusive to specific occupations. In fact, every job is potentially at risk of job strain, while at the same time (almost) every job can be organized in such a way that job strain is avoided. Assembly workers are probably the most typical example of employees who have a high risk of job strain. However, assembly work can be organized in such a way – for example by incorporating semi-autonomous teamwork and participation in decision making and by keeping work speed under control – that job strain is avoided. On the other hand, a university professor – often seen as a profession where job strain should be non-existent – could be confronted with job strain if her work is highly monitored, if academic freedom is being limited, and if her department is understaffed. In short, job strain can be easily ameliorated by policies, at the level of both the employing organization and the labour market in general.

From 1995 to 2010, Europe witnessed a general increase in the prevalence of job strain (from 9% to 12% in the general wage-earning population), although the increase has occurred to different degrees in different countries (see ). Countries with a consistently low prevalence of job strain are the Nordic countries and the BENELUX; countries with a high prevalence are found in Southern Europe, while Germany has also moved towards a higher prevalence of job strain. At the country level, it was found that among other factors, union density (percentage of workers who are members of a trade union) was protective against a high country-level prevalence of job strain, while the degree of unemployment was related to a higher prevalence of job strain (Vanroelen, Citation2015).

The case of precarious employment

Major macroeconomic and political transformations have led to the erosion of the so-called Standard Employment Relationship (SER; Benach et al., Citation2014). After the Second World War, the SER emerged as a type of “gold standard” of good employment; it included full-time permanent employment, a family wage, social benefits, strong regulatory protection, regular working hours, and opportunities for career advancement. According to most critical observers, the movement towards neoliberal macroeconomic policies was the main driver behind the decline of the SER model of employment (Harvey, Citation2005).

The transformation of employment under new structural macro-social conditions lead to the emergence of “precarious employment” at the bottom of the labour market. Precarious employment is not only related to the emergence of non-standard types of contracts (e.g. temporary and agency employment); it is a multidimensional phenomenon affecting various aspects of employment conditions and relations (Van Aerden, Moors, Levecque, & Vanroelen, Citation2013). It is argued that employment precariousness consists of seven dimensions: employment instability, low income, lack of social rights and benefits, de-standardized working times, low employability opportunities, lack of collective voice, and problematic interpersonal (power) relations (Julia et al., in press). Precarious employment can thus be conceived as a situation of accumulated unfavourable employment quality characteristics. Based on these dimensions, a typology of “employment quality” was created using cluster analysis techniques (Van Aerden, Puig-Barrachina, Bosmans, & Vanroelen, Citation2016). This resulted in five types of employment in the European labour force: standard employment, instrumental employment (involving few benefits and few training opportunities), portfolio employment (involving flexible working times and long working hours), unsustainable precarious employment (involving low wages and involuntary part-time work), and intensive precarious employment (involving adverse scores on each of the dimensions; Van Aerden et al., Citation2016).

These types of employment quality are clearly unequally distributed, with precarious jobs being more common in lower-skilled, lower-grade occupations and among young people (Julia et al., in press). Moreover, the types also show a clear country pattern, with the precarious types being more frequent in Southern and Eastern European countries and being the least common in Northern European countries (Van Aerden et al., Citation2013).

The typology also shows clear associations with characteristics of workers’ health and well-being, again showing the most adverse results for the precarious types and the most favourable outcomes for standard employment (Van Aerden, Moors, Levecque, & Vanroelen, Citation2015; Van Aerden et al., Citation2016). Moreover, the health associations of the employment quality typology show a clear age pattern. shows that precarious employment is far more strongly associated with adverse general health at older ages compared to younger ages. It should, however, be noted that the frequency of precarious employment is lower in the older age groups.

Conclusion

European labour market and retirement systems are being reformed in a context of demographic change (increasing life expectancy and an ageing workforce) and changing production models. This is leading to a trend of work intensification and greater flexibility in most European labour markets, while at the same time workers are supposed to keep working until later ages. Moreover, changes in the “world of work” are taking shape differently at the top and the bottom of the labour market, leading to “polarization” in terms of job quality. In this context, achieving sustainable employment is a difficult challenge, particularly for those workers at the lower end of the labour market.

This polarization, involving increases in job strain and precarious employment at the bottom of the labour market, is not a “natural process”. Both job strain and precarious employment are highly amenable to policy changes, as is demonstrated by important country differences in the prevalence and evolution of both phenomena. Policymakers pursuing a sustainable work agenda must therefore concentrate their efforts on the bottom of the labour market. Guaranteeing stable employment, avoiding contractual and temporal flexibility, and investing in the employability of the most vulnerable workers will pay off in the long run. In general, the entire working population could benefit from more efforts to make career breaks and work–family alignment more accessible. Finally, retirement ages should be differentiated according to the working conditions that workers have been exposed to during their careers. This is a matter of equity, given the strong relation between work-related risk exposure and the experience of chronic health problems and early mortality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Benach, J., Vives, A., Amable, M., Vanroelen, C., Tarafa, G., & Muntaner, C. (2014). Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 9–13. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500

- Burdorf, A. (2015). Understanding the role of work in socioeconomic health inequalities. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 41(4), 325–327. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3506

- Deboorsere, P., & Gadeyne, S. (2009). Sterfterisico’s naar beroep in België. Brussel: Interface Demography, Vrije Universiteit Brusse.

- Glei, D. A., Meslé, F., & Vallin, J. (2010). Diverging trends in life expectancy at age 50: A look at causes of death. In E. M. Crimmins, S. H. Preston, & B. Cohen (Eds.), National Research Council (US) Panel on understanding divergent trends in longevity in high-income countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2009). Job polarization in Europe. American Economic Review, 99(2), 58–63. doi:10.1257/aer.99.2.58

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford Univerity Press.

- Hauke, A., Flintrop, J., Brun, E., & Rugulies, R. (2011). The impact of work-related psychosocial stressors on the onset of musculoskeletal disorders in specific body regions: A review and meta-analysis of 54 longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 25(3), 243–256. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.614069

- Häusser, J. A., Mojzisch, A., Niesel, M., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2010). Ten years on: A review of recent research on the Job Demand–Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work & Stress, 24(1), 1–35. doi:10.1080/02678371003683747

- Hoven, H., & Siegrist, J. (2013). Work characteristics, socioeconomic position and health: A systematic review of mediation and moderation effects in prospective studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 70(9), 663–669. doi:10.1136/oemed-2012-101331

- Hurley, J., Fernandez-Macias, E., Munoz de Bustillo, R., & Al., E. (2015). Upgrading or polarisation? Long-term and global shifts in the employment structure: European Jobs Monitor 2015. Luxembourg: Eurofound.

- Ilmarinen, J., Gould, R., Järvikoski, A., & Järvisalo, J. (2008). Diversity of work ability. In R. Gould, J. Ilmarinen, J. Järvisalo, & S. Koskinen (Eds.), Dimensions of work ability. Results of the Health 2000 survey. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

- Julià, M., Vanroelen, C., Bosmans, K., Van Aerden, K., & Benach, J. Precarious employment and quality of employment in relation to health and well-being in Europe. International Journal of Health Services. April 2017:2073141770749. doi:10.1177/0020731417707491.

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. doi:10.2307/2392498

- Landsbergis, P. A., Dobson, M., Koutsouras, G., & Schnall, P. (2013). Job strain and ambulatory blood pressure: A meta-analysis and systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), e61–e71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301141

- Landsbergis, P. A., Grzywacz, J. G., & Lamontagne, A. D. (2014). Work organization, job insecurity, and occupational health disparities. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 57, 495–515. doi:10.1002/ajim.v57.5

- Malmusi, D. (2015). Social and economic policies matter for health equity. Conclusions of the SOPHIE project. Barcelona. Retrieved from: http://www.sophie-project.eu/pdf/conclusions.pdf

- Marmot, M. (2001). From Black to Acheson: Two decades of concern with inequalities in health. A celebration of the 90th birthday of Professor Jerry Morris. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(5), 1165–1171. doi:10.1093/ije/30.5.1165

- OECD. (2009). Sickness, disability and work: Breaking the barriers. Paris: Author.

- OECD. (2013). Mental health and work Belgium.

- Vallas, S. P. (1999). Rethinking post-fordism: The meaning of workplace flexibility. Sociological Theory, 17(1), 68–101. doi:10.1111/0735-2751.00065

- Van Aerden, K., Moors, G., Levecque, K., & Vanroelen, C. (2013). Measuring Employment Arrangements in the European Labour Force: A Typological Approach. Social Indicators Research, 1–21. Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0020731417707491

- Van Aerden, K., Moors, G., Levecque, K., & Vanroelen, C. (2015). The relationship between employment quality and work-related well-being in the European Labor Force. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 66–76. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.001

- Van Aerden, K., Puig-Barrachina, V., Bosmans, K., & Vanroelen, C. (2016). How does employment quality relate to health and job satisfaction in Europe? A typological approach. Social Science & Medicine, 158, 132–140. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.017

- Van Oyen, H., Deboosere, P., Lorant, V., & Charafeddine, R. (2011). Sociale ongelijkheden in gezondheid in België. Gent: Academia Press.

- Vanroelen, C. (2009). Work-Related Health Complaints in a Post-Fordist Labour Force. A sociology of work-related socio-economic health inequalities. Brussels: VUB Press.

- Vanroelen, C. (2015). Toenemende werkdruk. Een economische dwangmatigheid? In A. Van Regenmortel & K. Reyniers (Eds.), Te hoge werkdruk. Antwerpen: Intersentia.

- Vendramin, P., Valenduc, G., Molinié, A. F., Volkoff, S., Ajzen, M., & Léonard, E. (2012). Sustainable work and the ageing workforce. Luxembourg: Eurofound.