ABSTRACT

Small-scale enterprises (SSEs) are important for ensuring growth, innovation, job creation, and social integration in working life. Research shows that SSEs pay little attention to and have insufficient competence in workplace health management. From the perspective of managers, this study explores how external factors influence the development of this management. The article refers to a case study among eight Norwegian and ten Swedish managers of SSEs in the middle part of Norway and Sweden. We used a stepwise qualitative approach to analyse data, using an interpretive indexing of main categories. Two main categories were found to have an influence on the development of workplace health management: (1) restricted leeway and (2) commitments. Concerning the first main category, areas that managers highlight as important comprise the legal framework and regulations; workforce and market situation, production, economy; and occupational safety and health issues. Areas related to the second main category were advice from the board, guidance from mentors, work-related networks, and family and friends as buffers. One conclusion is that despite limited scope for developing workplace health management, managers find supportive guidance and inspiration from environments that are committed to helping them and their enterprise.

Introduction

Small-scale enterprises (SSEs) are important for Europe’s economy, and the European Commission considers them a key factor to ensuring growth, innovation, job creation, and social integration (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Citation2013a). In Sweden, approximately 900,000 individuals – more than one-fifth of the population working in the private sector – are employed in this enterprise group (Statistics Sweden, Citation2011). The corresponding figure for Norway is 550,000 individuals, which is one-fifth of the population working in the private sector (Statistics Norway, Citation2014). Because of this group’s importance to working life and SSEs’ less developed workplace health management (WHM), there is a need for more knowledge about how external factors affect WHM in this enterprise group. By WHM, in this article, we refer to actions taken by managers in the workplace to promote occupational health and safety (OHS), a good working environment, and employee health. According to various studies, SSEs represent a particular challenge in terms of working with OHS issues (Eakin, Lamm, & Limborg, Citation2000; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Citation2013b; MacEachen et al., Citation2010). Studies have shown that most SSEs pay little attention to OHS issues (Andersson & Hägg, Citation2006; Breucker, Citation2001; Frick, Langaa Jensen, Quinlan, & Wilthagen, Citation2000: Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006) and that specific strategies are needed to implement solutions in SSEs (Breslin et al., Citation2010; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, Citation2013b). Similarly, research also suggests that SSEs have limited competence in creating health-promoting workplaces (Landstad, Hedlund, & Vinberg, Citation2017; Moser & Karlqvist, Citation2004; Torp & Moen, Citation2006). Nevertheless, the European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (Citation2001) states that SSEs have a unique ability to affect employee health positively because of factors such as the family atmosphere and SSE managers’ immediate control of working conditions. In addition, Meggeneder (Citation2007) argues that small enterprises have organizational characteristics that are suitable for introducing and implementing workplace health promotion. Thus, the research has arrived at contradictory results regarding SSEs’ ability to develop WHM.

According to Sverke (Citation2009), Scandinavian work-environment regulations emphasize a consensus model according to which a motivated and harmonized workforce will result in long-term organizational effectiveness. Trade unions and employers are therefore the most important stakeholders, operationalizing public policy regulations and transforming them into practice (Hasle, Limborg, & Nielsen, Citation2014). Legislation indicates that both employers and employees have a general responsibility to create a sound working environment as part of maintaining a general ‘license to operate’ (Hasle et al., Citation2014, p. 74). State regulation of the working environment in both Norway and Sweden requires a working life and working environment that provide the basis for a healthy and meaningful working situation (The Norwegian Working Environment Act, Citation2015; The Swedish Working Environment Act, Citation2014). Managers in SSEs may have low competence (Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006) but good organizational conditions for developing healthy workplaces (Meggeneder, Citation2007). This makes it important to gain knowledge about how structural and external factors affect managers’ internal conditions and possibilities for WHM. The same applies to the manner of managers’ reasoning and priorities. Managers of SSEs usually have limited human-resource management, economic resources, and elbow room for manoeuvring. Consequently, they may have to balance on a fine line – like a tightrope walker – to meet different requirements of the enterprise, such as creating a foundation for a healthy workplace, keeping the budget within its limit, maintaining a good market position, and being oriented towards customers.

Research indicates that the SSE manager (who is often the company owner) is a key person because his or her opinions and values influence the company’s approach to health and safety improvements (Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006). However, holding a managerial position in an SSE often involves long and irregular working hours (Gunnarsson, Vingård, & Josephson, Citation2007: Nordenmark, Vinberg, & Strandh, Citation2012), along with high and conflicting work demands (Bornberger-Dankvardt, Ohlson, & Westerholm, Citation2003; Stephan & Roesler, Citation2010). Several of these conditions may hinder the implementation of health-promotion practices in the enterprise. In addition, SSE managers may consider these practices and working-environment regulations and demands as a financial burden that is too heavy for a small enterprise to bear (Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006). Based on the above-mentioned characteristics in SSEs, it is important to gain more knowledge about how external factors influence the development of WHM. By external factors, we mean legal regulations, the market situation, or personal circumstances.

Aim and research questions

This study’s overall research aim was to explore which and how external factors affects managers’ ability to develop WHM in SSEs. We focus on the following research questions:

RQ1:

Which external factors have an impact on WHM?

RQ1:

How do these external factors affect WHM?

Key concepts

The Ottawa Charter defines health promotion as ‘the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health’ (WHO, Citation1986). This definition approaches health not only as an absence of disease, but also as a resource in everyday life that includes physical, mental, and social well-being and capacity (Eriksson, Citation2011).

There is no consensus on the definition of WHM. Jiménez, Winkler, and Dunkl (Citation2016) assert that WHM consists of a set of leadership behaviours that is in continuous interaction with the working environment, with the goal of designing that environment to enhance employee health. As stated, we regard WHM as the actions taken by managers in the workplace to promote OHS, a good working environment, and employee health. External factors refer to factors that affect WHM in SSEs from the outside, that is, the market, financials, business sector, legislation, or the personal circumstances of managers. SSEs are defined as enterprises employing fewer than 20 people (EU, Citation2003).

OHS consists of strategies to reduce ill health at work. This can be achieved by promoting the use of systematic managerial processes to detect and abate workplace hazards and actively manage the quality of the overall work environment (Frick et al., Citation2000).

Previous research: WHM

Employers now generally consider a reasonable working environment a prerequisite for legitimacy among the organization’s stakeholders (Almqvist & Henningsson, Citation2009; Frick & Zwetsloot, Citation2007). Research shows that companies must pay close attention to WHM to prevent sickness and create healthy workplaces (Department of Health, Citation2004; Holt & Powell, Citation2015; Lindström, Schrey, Ahonen, & Kaleva, Citation2000). A literature review concludes that active management, the involvement of all staff, and comprehensiveness in measures are success factors for implementing health-promoting practices (Chu et al., Citation2000; Sparling, Citation2010).

Currently, there is also increased attention on the development of SSEs and their investments in health and the working environment (Abrahamsson, Citation2006; Hasle, Limborg, Kallehave, Klitgaard, & Rye Andersen, Citation2012; Witt, Olsen, & Ablah, Citation2013). However, several studies indicate that health-promotion practices are less developed in SSEs, and there are several reasons for the low involvement of small enterprises in health-promotion issues (Griffin, Hall, & Watson, Citation2005; Moser & Karlqvist, Citation2004). They lack the motivation and resources to work with health issues, there are few organizational mechanisms for communication, and they have limited resources to devote to occupational health issues (Breucker, Citation2001; Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006).

Improved safety and product quality were the original goals of WHM (Rootman et al., Citation2001). Later, this concept was developed into various approaches to improve employees’ health. According to Gjerstad and Lysberg (Citation2012), in recent years, WHM has received increased attention in the Nordic countries. Managers influence the interaction of individual and organizational aspects. Important concepts include health awareness, workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values (Jiménez et al., Citation2016). Managers who work with broader intervention strategies exert a greater influence on outcomes related to employee health than managers do who work with more one-dimensional strategies (Dellve, Skagert, & Vilhelmsson, Citation2007; Grawitch, Gottschalk, & Munz, Citation2006). However, a review of studies in the Nordic countries revealed that most studies had an individual focus on changing workers’ lifestyles or behaviour by using a top-down approach that does not focus on settings-related factors (Torp, Eklund, & Thorpenberg, Citation2011). In addition, the SSE workplace is a challenging context for managers. They must consider various factors when they work with health-promotion issues at the workplace, such as the number of employees, business age, structure, workforce, manager centricity, and culture (Cunningham, Sinclair, & Schulte, Citation2014, p. 148).

According to a qualitative study of SSEs, managers try to adapt the workplace for sick employees (The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate, Citation2012). However, their experience is that the role of the Social Insurance Agency and their own coordinating role are unclear (The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate [Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring], Citation2012). In addition, OHS research shows that only 10–55% of Swedish employees in SSEs have access to occupational health services (OH) Gunnarsson, Andersson, & Josephson, Citation2011. The Norwegian workforce displays a similar tendency (Moen, Hanoa, Lie, & Larsen, Citation2015). One consequence of these facts is that many SSEs engage in only a limited use of these resources. Studies of health and safety practices in the workplace identify several factors that either hinder or facilitate implementation (Whysall, Haslam, & Haslam, Citation2006). Hindering factors include management commitment, managers’ general attitudes towards health, insufficient resources, and prioritization of production. Facilitating factors include supportive managers, local control over budget spending for health, and good communication among managers and co-workers (Whysall et al., Citation2006).

Many managers in small-scale enterprises cooperate locally in professional networks (Gunnarsson, Citation2010). Regional or local professional networks may improve health and safety in small enterprises (Vinberg, Citation2006). The characteristics of long-lasting networks are trust, good relations, and usefulness to entrepreneurs (Antonsson, Birgersdotter, & Bornberger-Dankvardt, Citation2002). The results from a study of three Danish networks on OHS issues (Limborg & Grøn, Citation2014) indicate that small enterprises are more affected by the actions and attitudes of their competitors and collaborators within their industry than by general campaigns, regulations, and visits from the Labour Inspectorate. The authors conclude that this result suggests the need for reconsidering or supplementing the previous strategy towards SSEs, which in general has closely matched the strategy towards large enterprises. A new strategy should include support for the establishment and should facilitate networking between similar companies that can support the companies’ joint effort to achieve a common commitment to satisfy health and safety standards (Limborg & Grøn, Citation2014).

The position of this study is to explore and contribute to knowledge about how mentioned external factors contribute to development of WHM in SSEs. Research about WHM and OHS in SSEs has more been focused on management culture (Meggeneder, Citation2007) and internal workplace-related strategies (Frick et al., Citation2000; Landstad et al., Citation2017).

Method

This study analysed interview data from managers in 18 SSEs in central regions of Norway and Sweden. The methodology used to study conditions for creating WHM was based on a stepwise inductive method (Patton, Citation2002; Tjora, Citation2012). This means that analytical categories are not stipulated in advance (Patton, Citation2002; Tjora, Citation2012) but rather through a stepwise process. The researchers did not use predefined themes, but instead identified and extracted data across the empirical material based on their purposefulness and relevance to answering the research questions (Patton, Citation2002; Tjora, Citation2012). We searched for patterns and concepts that echo patterns found to answer the research questions. Eventually, we relabelled these patterns and concepts into categories linked to adequate theories and reanalysed them. The goal was to generate and derive subtopics that reflected patterns found in the data analysis and then to relate them to pertinent theories and research so main categories could be constructed. In the analysis section, we give further details on this process.

The foundation for the analysis was the similarity of verbal references among the participants’ or managers’ viewpoints, but representing empirical contours that are more typical or general for the strategic sample. All of the enterprises investigated participated in a WHM project intended to give managers improved skills and competence in health, safety, and work-environment issues. One Norwegian and one Swedish OH led the project, and the focus was on management issues, psychosocial working conditions, and employees’ health. Components of the project were investigations of working conditions and employee health, network meetings, and leadership support.

This article does not present data from the intervention study. Instead, the focus is on what managers identified as their possibilities and obstacles for WHM, including knowledge gain from the intervention.

Recruitment criteria

To ensure a wider range of SSE manager types in the strategic sample, we recruited managers from different branches of the private sector. We recruited informants from SSEs in Norway and Sweden who agreed to participate in an intervention project on WHM in SSEs. One selection criterion was that the enterprises had no more than 20 employees. Further criteria were that the enterprises employed both sexes, that they were located in the middle of Norway and Sweden, and that they represented different types of services in the private sector (see ). The sampling is qualitative and is not intended to be representative.

Table 1. Descriptions of sample participants’ criteria

Data collection

We collected data between March and May 2015 from eight managers in Norway and ten managers in Sweden. The data-collection method was focused informant interviews (Denzin, Citation2001; Tjora, Citation2012). The interviews lasted from 90 to 120 minutes, and they were conducted at a location convenient for the participants (Patton, Citation2002, p. 341).

We used an interview guide to collect data. The guide involved asking for managers’ experiences and reflections on external factors that influenced their WHM and how those factors either affected their opportunities or presented obstacles to the creation of a health-promoting workplace. Immediately following the interviews, the tape-recorded interviews were transcribed.

Analysis

We used a stepwise method when analysing the data (Charmaz, Citation2000; Mason, Citation2002; Tjora, Citation2012). Stepwise analysis provides a flexible, heuristic strategy (Charmaz, Citation2000, p. 510) for analysing meaning and interpretation in data material. We used this strategy because we continuously compared utterances and the expressed experiences in the data and searched for patterns of meaning about the research questions (Patton, Citation2002). Below, we introduce the analytical steps in the order in which they were performed.

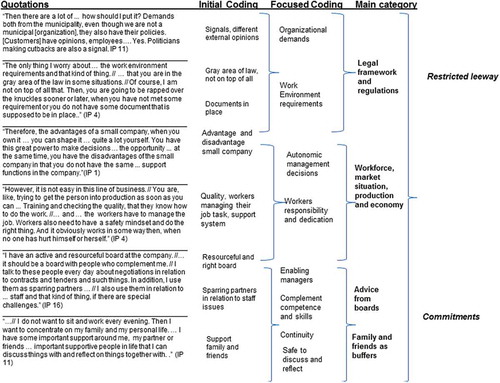

The first step was to conduct a naive reading of the data to determine distinct patterns or displayed commonalities. The next step was to read these distinct patterns or displayed commonalities thoroughly and then search for condensations of meaning and differences in condensation to describe and compare the data. In this analytical step, we analysed the distinct patterns that seemed to form main categories and sub-topics of a main category. The first and second authors individually evaluated the credibility of their understandings of the analytical categories, critically challenging them and searching for alternative patterns that could likewise be applied (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2006; Tjora, Citation2012). These researchers analysed data through a creative and interpretative process. Together, they then constructed the main categories, categories, and their sub-topics (Charmaz, Citation2000). The first and second author compared notes for analysing data to glean a more nuanced outline of the core descriptions and categories (initial coding). Then all three authors discussed and agreed on the codes and focused coding. This process was repeated and modified until saturation was reached and the categories were validated (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Mason, Citation2002; Patton, Citation2002). illustrates the coding and stepwise forming of categories, as described in more detail in the following section.

Ethics

Sweden’s Regional Ethical Committee, Department of Medical Research approved the method design of the study (Dnr 2014-28-31M). The informants gave written consent to participate in the study. The informants were informed about their right to withdraw from the study without giving any reason. We immediately anonymized identifying data in the transcriptions of the interviews. All of the data were properly stored according to the Swedish Act on Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans (SFS 2003:460).

Findings

The analysis showed that two main categories were relevant to the research questions: (1) restricted leeway and (2) commitments. Below, we present each category in relation to its focus area in the main category. We also describe the categories and their sub-topics at varying lengths. This is, however, an expression of variation in characteristics and their links to the main category. The length of the descriptions should not be seen as a sign of difference or less significance.

Category 1: restricted leeway

This main category addresses external factors that affected the managers’ leeway to model WHM. It refers to factors that managers considered important but out of their control. These factors structured the managers’ room to manoeuvre.

Legal framework and regulations

When managers searched for appropriate tools to prevent illness and form a health-promoting workplace, they needed simultaneously to comply with public regulations and rules. These regulations appear to create a “Gordian knot” for some managers.

Then there are a lot of … how should I put it? Demands both from the municipality, even though we are not a municipal [organization], they also have their policies. [Customers] have opinions, employees … Yes. Politicians making cutbacks are also a signal. (IP 11)

Managers experienced anxiety about not following regulations to ensure a safe working place and the rules in the Working Environment Act. These rules and requirements may seem overwhelming, given the reality of SSEs.

It is just that when you are a small business … all these rules about the work environment. … They can be a huge burden because they are the same rules as for a big company. In a way, there should be a work environment … a “light” version of the work environment for the small company. Do not get me wrong, I do not mean that the employees should be any worse off. (IP 3)

Managers want to ensure a safe working environment for their employees and develop a healthy workplace. However, they experienced that it was difficult to follow rules and the various legal frameworks that governed them.

The only thing I worry about … the work environment requirements and that kind of thing … that you are in the grey area of the law some situations. Of course, I am not on top of all that. Then, you are going to be rapped over the knuckles eventually, when you have not met some requirement or you do not have some document that is supposed to be in place. (IP 4)

This subcategory shows how managers experienced limitations in relation to complying with working-environment legislation related to other regulations and the company’s regular business.

Workforce, market situation, production, and economy

Managers communicated how they need to manoeuvre in a market situation in which seasonal work is more common and sector-specific fluctuations influence employment. These external factors interfere with managers’ freedom and flexibility to address WHM in a way they find valuable.

Therefore, the advantages of a small company, when you own it … you can shape it … quite a lot yourself. You have this great power to make decisions … the opportunity … at the same time, you have the disadvantages of the small company in that you do not have the same … support functions in the company. (IP 1)

Managers experienced that they had insufficient support functions related to workforce and production, for example human resources, administrative support, and economy systems. Because of the size of their enterprises and sector-specific conditions, managers cannot afford to lose employees during certain periods significant to production. It was a challenge for such managers to reorganize workloads due to sickness or to obtain new qualified employees for reasons related to SSEs’ lower employee numbers. Managers relied on employees and their qualifications to maintain a favourable market situation. Employees’ adaptation to multiple roles and their interdependent place in a team’s productivity rendered managers dependent on their work capacity.

However, it is not easy in this line of business. You are, like, trying to get the person into production as soon as you can … Training and checking the quality, that they know how to do the work … and … the workers have to manage the job. Workers also need to have a safety mind-set and do the right thing. Moreover, it obviously works in some way then, when no one has hurt himself or herself. (IP 4)

Managers stated that the financial situation of the enterprise could affect how they addressed absence among employees and if they could hire contract workers.

Then, we have a financial situation today that allows us to do that. It was not like that when I started as the manager – it was a hard slog for the first few years to get everything together. Now, we have an upward trend where we are still managing – and a bit more. Therefore, there is the opportunity … then we can hire extra staff, and we do not have to wear ourselves out every day. (IP 6)

Managers do not have sufficient time to address safety and healthy activities in the workplace because they are busy in the “production line”. They were often the ones who were most qualified to make judgements about the market and what to do to achieve a favourable position compared to competitors. Managers also stepped into the core business in case of sickness or other types of absence.

Many people ask me, “Yes, but what, as the CEO – what do you do then?” “I buy coffee, run the sweeper, and fetch the laundry” … Yes, I am actually a – I am really more of a facilitator, trying to make sure that everything around this group works as well as possible. If I create the right situation for them, they will do a fantastic job. Like, I make sure that as little as possible gets in their way. (IP 10)

Managers were constantly present and active in their efforts to develop the enterprise, keep it going, adapt to the market, and be efficient. In the current economic situation, although managers had a heavy workload, they tried to create a psychosocial working environment that was flexible and adaptable to the needs of both managers and employees. Several managers demonstrated an almost entrepreneurial willingness to make their enterprise a flexible workplace – a place characterized by solidarity and tolerance.

This has just strengthened my interest in carrying on, whatever I do for the rest of my life, that you see that you are creating a flexible environment in which you are open to changes … to be able to adapt to them, that is very important … it is a bit … what you read about, many Silicon Valley companies. There is a lot of flexibility. In that respect, that is what I am driven by, creating an effective and flexible environment. (IP 2)

It is expensive for SSEs to have employees on sick leave. Therefore, several managers worried about how they could prevent illness and adapt the work so that sick leave did not occur. The diverse responsibilities for managers made them feel they were working in the interest of the entire enterprise when working proactively to prevent prolonged sick leave among employees.

I depend on people coming to me and letting me know … when people do not do that, we have experienced several times that people push themselves too far, and then they are on full-time sick leave for a long period. Then, I think that if they had spoken up a bit earlier, perhaps they would have had part-time sick leave and perhaps for a shorter period as well, if they had spoken up earlier. (IP 11)

In this subcategory, the managers described how they have limited resources to work with health and safety issues and sick leave. Managers often have to work in the production line to maintain market position and ensure adequate quality and financial solidity. The leaders are therefore interested in being a flexible facilitator and ensuring good working conditions for their employees, such as a trustful relationship to managers, and to provide adjusted work tasks to employees with reduced capacity, thus creating a health-promoting workplace.

Occupational safety and health issues

The managers stated that OH represented an unused opportunity for preventing illness and promoting health in the workplace. The managers were aware that this was unused potential. They had good experiences with this service when participating in the intervention program. As mentioned above, these managers participated in an intervention program intended to improve their skills and competence in health and work environment issues. Through this participation, managers gained access to and signed agreements with qualified persons from OH providers. Managers received help and support to promote health in the workplace and obtained a different perspective on OH issues.

The contact with the OHS – I think that perhaps helps me to be a little clearer as a manager … The three-day courses, they have helped me a lot as a manager in relation to employees … I mean, the perspective … not that I had a bad perspective before, but it has influenced the way I see employees. How to work with employees in wise and sensible ways. (IP 11)

In addition to new awareness and insights, managers experienced the benefit of using the OH for preventive purposes. Employees could obtain external expertise if needed.

This project has been good … in the same way that I can buy health examinations, I can buy help from a psychologist … if one of my staff members is having a hard time with something, needs to talk, and I cannot take that on. I mean, one has cropped up … it is important to be preventive … to work more before a problem arises to create a better framework. (IP 1)

Managers considered it important to have access to OH because in doing so, they gained partners to consult before problems could occur, a consulting body from which they could obtain advice and discuss appropriate measures.

…if one has a black day, I can phone one of [name staff members at a local OHS] … I can talk a bit about the project we are running as a team to obtain some new ideas and get motivated. That is quite fun… [laughter]. (IP 16)

For managers, it was particularly important to get support from OH when employees had recurring health problems and needed partial sick leave. In these cases, managers needed advice for helping these employees could return to full-time work when possible.

Some people who are ill … with sick notes and several challenges and we have some employees who have some health-related challenges that we must address. After we started this collaboration, we became an IA business [“IW” enterpriseFootnote1]. Therefore, we now have a few more tools to help us through NAV and things like that. (IP 16)

Most managers have previously worked preventively by buying tailored health insurance. This health insurance would pay for prompt treatment when an employee became ill or had an accident.

I tried to tackle it the easy way. So we have this sickness … Wait … but heavens, what is it called now … I was sitting with all these insurance schemes for this “go to the front of the queue” insurance, as it is popularly called, allowing you to get treatment quickly … It is a kind of insurance, illness insurance… (IP 4)

In Norway, some managers expressed satisfaction with their experience of being part of a public cooperation agreement for a more inclusive working life (i.e. with being part of an IW enterprise). The main goals of such an agreement are to improve the working environment, prevent and reduce sick leave, and prevent exclusion and withdrawal from working life.

It was the [name OHS] who began saying that we should have a meeting with the working life centre at NAV and go on to become an IA business [IW enterprise]. There is not, at least as I saw it, very much to consider, because it does not cost anything. There are only benefits from being included in the system … After all, our aim must be to be a business where people can work until they are pensioners. It should be possible to create a basis for them to have a good workday and a secure future until they retire. (IP 16)

Sometimes, managers found it difficult to prioritize OHS issues because so many tasks needed their attention. Another difficulty was that they did not have time to obtain specialized knowledge in this field and sufficient administrative qualifications.

…In a bigger company, there you usually have a Human Relations [HR] function where you can get support, you have a finance department … and you might also have executive colleagues if you are the CEO. Therefore, there are … more organized support functions that you can use in a larger company. (IP 1)

Working with health and safety issues in the workplace was a job that fell to the managers, although they did not necessarily feel they were trained or qualified to do so. The result was a great deal of firefighting and spur-of-the-moment work when managers addressed these issues.

A small company always receives a failing grade when it is compared with a big company that has a HR department, a finance department, and various special functions. We are the same person with a hundred functions instead … we must satisfy the tax authorities, we must satisfy the work environment authority, and there is the chemicals agency, and there is … [laughs] the customer. The customer is the most important, after all, because if we did not have that, the company would not exist … no work-environment work would exist either. (IP 3)

This subcategory shows how the managers experienced restricted leeway that made them “tightrope walking”, especially when dealing with health and safety issues at the workplace. This is partly due to managers having limited possibilities to gain knowledge of and qualifications for working preventively with such issues and partly because they did not have sufficient knowledge about how to use the public social insurance systems and OH providers .

Category 2: commitments

This category addresses managers’ external engagements that were not directly related to the enterprise but influenced the managers’ method of developing WHM. When managers developed WHM, personal engagement outside the enterprise had an impact on how they prioritized and focused. Managers who owned their enterprise expressed the view that the entire workplace relied on their efforts. For this reason, managers were eager to invest in affordable health and safety equipment if it would benefit the entire enterprise. The impact of commitments outside the enterprise involved personal relationships. The managers received advice and correction from family members and friends; this information was useful because it came from people who knew them and the business well and wanted them to succeed.

Advice from boards

Boards were something all enterprises had. They played an important role in enabling managers to obtain advice on any issue. Some boards provided managers with a regular dose of corrections and a reality check, with a “kick in the pants” for managers to behave appropriately and within the board’s framework and directions. Several managers found that the board provided important guidance and advice both in relation to how to develop the business and in how they should invest in human relations.

I have an active and resourceful board at the company … it should be a board with people who complement me. I talk to these people every day about negotiations in relation to contracts and tenders and such things. In addition, I use them as sparring partners … I also use them in relation to … staff and that kind of thing, if there are special challenges. (IP 16)

Because their jobs were lonely and difficult, managers usually took the board’s advice. They needed someone to team up with who was familiar with the enterprise and its type of business.

…This is an issue that many small business owners have, that you are pretty much on your own on some issues … there is an advantage of having a board … in that forum; it is the advantage of bouncing off ideas and thoughts with somebody who knows the company well. Speaking for myself, it is important to create some structure there, where you can find support. (IP 1)

Some board members were especially supportive and important to managers. The board chair appeared to play such a role, and the use of this person to discuss difficult personnel matters or difficult cases at the workplace helped managers focus. The board chair appeared to be an important adviser because he or she was well acquainted with the enterprise, could give qualified advice, and was therefore a person to whom the managers easily turned. Continuity and a good understanding of the enterprise were important qualities of board members if managers were to use them for advice and guidance. This was particularly important to managers with respect to obtaining advice about how to handle conflicts and challenges in the working environment.

In addition to continuity and familiarity with the board members, it was important for the managers that the board members did not change too often.

Most have stayed; some have been replaced, but the backbone has always stayed. That is a bit reassuring because then you know that the board will not come in and turn everything upside down. (IP 6)

This subcategory related to external boards and board members and how these affect both managers and matters of importance to WHM. The board, particularly the chair, gives managers important input and advice about what is essential or insignificant.

Guidance from mentors

Managers mentioned mentors as significant in helping them develop the enterprise and gain support in their daily business. Although mentors needed to be at a distance, it was also necessary for them to be sufficiently close to dilemmas and issues that might arise for a manager in this business.

I have found them through [name of Swedish business association] … it has been fantastic. Incredible support: I ask for it, and then I get help. Yes, things happen that I have to tackle in different ways, so that they … oh, it has been good. Here, you have to work everything out yourself. It is very important to know so much in all areas. Therefore, mentors are good. (IP 9)

Mentors may have an outsider’s perspective on managerial challenges. In this way, managers can obtain an overview and strive for a role model.

…He was my greatest mentor until he died. There was no need to be in touch all the time, but when something cropped up, then he … always had time somehow. It is important to have someone you can confide in. (IP 8)

It was important for mentors to have management experience, insight, and maturity.

…You have a contact network outside your own things, so you aren’t snowed under in your own … without having to have … well, mentors then. I have always had mentors, always had. Both when times have been really tough … then you really need honest mentors. I have had that. (IP 8)

This subcategory linked to managers who sought advice and direction about WHM from external mentors. It was important for the mentors to have personal involvement in the challenges faced by the managers and to be able to provide qualified advice and comprehensive analysis, thus providing the managers with direction.

Work-related networks

Managers could participate in various types of business networks. These could be industry-specific networks or networks targeted at female managers. It was important to develop work-related networks, particularly in relation to personnel management and other conditions that could affect the work environment.

We have a networking group with 12 [managers]. It is fantastically useful. We meet about every sixth week … for a period of a few years, we have worked with professional development, professional focus and a professional boost. However, we can also bring up cases involving problems at our own places. For example, I need some guidance about follow-up with staff on sick leave and how do you do it … we can discuss that. (IP 11)

Some managers participated in formal networks, whereas others used informal networks. In both cases, networks were used to discuss general matters regarding WHM, not individual cases or staff matters.

Managers found they could usually benefit from networks in the same industry, but that did not apply to advice related to the psychosocial working environment. It was equally valuable to discuss these questions with networks and managers from other industries.

It helps you to develop, to meet colleagues, especially those who are in the same situation. In completely different lines of business – like now – it gives you quite a lot, I think. The problems, they are the same everywhere it seems. As far as the psychosocial part is concerned – how to manage staff and so on. (IP 8)

This subcategory includes formal or informal external networks that affect managers in developing the workplace in a health-promoting direction. Commitment and dedication were characteristic of managers and those involved in the networks, and this made it easier to utilize the knowledge represented by these networks. The networks did not have to be in the same industry for managers to benefit from them. The managers knew which questions were best suited to address in the different networks. In some cases, it was advantageous to receive advice from someone who was not a competitor or working in the same industry.

Family and friends as buffers

Managers noted how family, friends, and partners gave valuable advice and guidance for how to engage in the enterprise, how to commit in a manner that balanced their personal engagement with engagement in the enterprise, and how to correct their behaviour in a way that would promote better health and work–life balance for themselves and their employees.

Someone at home puts on the brakes. My husband might say that “Yes, it would be nice if you were at home some evenings too”. Nevertheless, every now and then, he comes here, and we help each other. (IP 9)

Friends or family had in-depth knowledge about the manager from their personal relationships. Some managers found that this helped them respond more reflectively to the issues they discussed.

I do not want to sit and work every evening. Then I want to concentrate on my family and my personal life … I have some important support around me, my partner or friends … important supportive people in life that I can discuss things with and reflect on things together with. (IP 11)

Managers found it fruitful to have someone outside the enterprise to talk to about their everyday work and found that friends gave them new ideas and energy because they draw attention to the positive aspects of working in a stressful environment.

It is wonderful to have [female] friends who know me well. They see me in a different way from how my staff sees me, so I have found my support there. Because they may have seen that “but how are things?” or “now we must do something fun” … you can pour out everything on your mind. They are good. Everything feels much better afterwards [laughs]. (IP 9)

Family ownership and close relationships with family members can influence managers’ behaviour and management practice. Although family members can relieve managers in their work tasks, this could have been problematic if managers had a strained relationship with family members who had previously led the enterprise.

This subcategory was associated with external buffers that assist the managers in the development of WHM by guiding them to balance between their different skills and qualifications, and work–life balance for themselves and their employees. The buffers came from private relationships, friends, or family who made managers aware of their own need to care for their family lives, not only the workplace’s needs. In that way, the managers received important correctives about how to organize their daily lives and focus on universal measures for WHM.

Discussion

From a managerial perspective, this study explores which external factors influence the development of WHM and how these factors have an impact. From earlier research, we know that SSEs pay little attention to OH issues (e.g. Frick et al., Citation2000; Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006) and have insufficient competence to create health-promoting workplaces (Moser & Karlqvist, Citation2004; Torp & Moen, Citation2006). This study’s findings explain that working environment regulations, market situation with sector-specific fluctuations, insufficient time and limited resources to address health and safety activities, and insufficient knowledge about how to get support from occupational health services and social insurance system restrict SSE managers’ leeway to engage in WHM. Managers want the best for their enterprise and its employees and want to provide a healthy workplace, even if this aim can be difficult to fulfil. According to the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (Citation2013a), SSEs have a beneficial position in working life. This study confirms that managers partially agree with that statement. Nevertheless, as this study confirms, SSE managers can experience the demands of OHS regulations both as a financial burden and as too bureaucratic (Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006; Hasle et al., Citation2012, Citation2014). The managers studied here experienced difficulties in considering all types of legal requirements and in implementing OHS regulations. This is partially attributable to their lack of flexibility and ability to migrate these requests and regulations into the reality and conditions of small enterprises. The managers lack both the time and appropriate methods to implement these regulations. Managers note that it is difficult to prioritize OHS regulations while focusing on important external factors such as market changes and sector-specific fluctuations in the requirements for the enterprise. This finding is in accordance with a study by Tappura, Syvänen, and Saarela (Citation2014), who found that high economic pressure and a lack of resources were the most significant factors that affected managerial ability to design workplaces and promote employee health.

Managers explained that they lacked the competence, but not the willingness to develop skills in WHM because of a work overload, the need to accommodate other priorities, and a lack of administrative and management resources. However, they were eager both to learn more and to share knowledge with managers from other companies about psychosocial working conditions. Managers expressed a need to pay more attention to developing a health-promoting workplace and were highly motivated but lacked the capacity to do so. This finding is in accordance with other studies underlining how managers must be supportive, hands-on, and inclusive to create a health-promoting workplace (Jiménez et al., Citation2016; Skarholt, Blix, Sandsund, & Andersen, Citation2015).

In this study, OH services were an important external factor that the managers could utilize better to create a good work environment and a healthy workplace. Other research studies show great heterogeneity among SSE managers regarding the priority of work-environment issues (Hasle et al., Citation2012). In our study, managers explain why this can be the case: they lack appropriate regulations, tools, and resources to improve the work environment. In addition, they did not have sufficient information and knowledge about how to use the OH. SSEs in Norway and Sweden are affiliated with OH only to a slight degree (Gunnarsson, Citation2010; Moen et al., Citation2015). However, as shown in this study, that situation can easily change. Managers pointed to the experience they had gained from being exposed to a workplace health intervention led by OHS and indicated that this was a door opener for obtaining assistance in difficult WHM issues. Participation in a health intervention project provided them with new experiences and increased awareness and knowledge about how to benefit from OH services. Therefore, there is a potential for OH to develop adjusted services for SSEs. Research shows that efficient collaboration between enterprises and OH is dependent on a continuous dialogue, where the services had to be to be flexible and adjusted to enterprises’ needs (Schmidt, Sjöström, & Antonsson, Citation2011).

The managers of the SSEs in this study, especially Swedish managers, referred to their restricted ability to use methods provided by the social security system to prevent sickness and ill health. According to Ahlberg et al. (Citation2008), the absence of rehabilitation procedures is an important aspect of the difficulty of reducing sick leave. However, an interview study among SSEs showed both that they were unsure of how to utilize the resources offered by the social security system and that they did not know what these public authorities could offer SSEs (The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate [Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring], Citation2012). Norwegian managers expressed a need to sign a formal agreement with the social security system so they could better benefit from it. Engaging in a long-term relationship with the social security system and working with that system to prevent or avoid long-term health issues was an overlooked aspect of managers’ efficacy. Some managers buy private health insurance for their employees instead of relying on the public system.

The managers in this study emphasized commitments based on external factors, including the engagement of board members, mentors, business networks, and family and friends. These external factors and commitments support managers in WHM. Research indicates that networks can be a way of improving health and working environment in SSEs (Vinberg, Citation2006). Trust and close relations are important in these networks if they are to be long lasting (Antonsson et al., Citation2002; Street & Cameron, Citation2007). According to Limborg and Grøn (Citation2014), it can be an advantage to have networks of enterprises in the same sector when seeking solutions to sector-specific problems in the working environment. In our study, managers valued the exchange of experience with their counterparts from other sectors when they discussed issues relating to the psychosocial working environment. It is noteworthy that the managers in this study referred to friends and families who caused them to be reflective in their management and to balance their obligations to the enterprise, employee issues, and their own personalities. This managerial reflectiveness is important to the development of WHM (Larsson & Vinberg, Citation2010). For example, managers reflect about leadership behaviour and how they foster a positive culture in the enterprise.

The managers in this study considered WHM to be an area in which they strived to balance independence, requests from individual employees, and the requirements of official regulations and the market situation. They emphasized the need to consider both individual-directed and organization-directed tools, which is in line with Jiménez et al.’s (2016) finding that managers influence the interaction of individual and organizational aspects. Therefore, it is difficult for SSE managers to cope with WHM.

It is possible to reflect on this study’s findings in relation to theoretical aspects of organizational health. According to Lindström et al. (Citation2000), organizational health implies that an organization can not only optimize its effectiveness and the well-being of its employees but also cope effectively with both internal and external changes. In this study, the managers seem to realize the connection between employee well-being and organizational outcomes and the importance of employee health and working capacity. However, they point to several obstructing factors such as the lack of flexibility in working-environment regulations, market fluctuations, the firm’s financial situation, the lack of service from external resources, and managers’ demanding working conditions. One interesting result is that the managers are more likely to obtain external support from the board, mentors, networks, family, and friends than from, for example, OH, which was created to assist enterprises with their health and safety issues at the workplace. In future models for WHM in SSEs, it will be important to find ways to cope with the obstructing factors found in this study and to consider SSE managers’ external support systems so that they can be assisted in developing both to WHM and a health-promoting workplace. However, another contribution of this study is that models for WHM and theoretical aspects of leadership theory must consider the special nature of the culture of SSEs and their managers’ special challenges. In many SSEs, the manager is also the owner, and his or her beliefs and cultural values provide the guidelines for developing the enterprise (Hasle & Limborg, Citation2006). Being an owner-manager often means a large amount of responsibility and a high workload that can lead to stress and ill health (Gunnarsson et al., Citation2007; Nordenmark et al., Citation2012). Therefore, models for WHM in SSEs also must focus on measures for improving the working conditions, lifestyle habits, and health of managers, not just those of employees.

Conclusions and implications

Our conclusions are related to the research questions about which external factors have an impact on WHM and how these impacts work. One conclusion is that rigid working-environment regulation and laws, a lack of tools and methods, and limited use of OH and the social security system are hindrances to WHM. Nevertheless, the managers in this study expressed high awareness and willingness to develop skills and knowledge about WHM. Another conclusion is that external commitments from the board, mentors, networks, and family and friends are crucial and a resource for how managers develop a health-promoting workplace. Additionally, the societal support system for WHM does not seem to recognize SSEs’ special characteristics. Managers must therefore learn to walk as equilibrists, such as developing competence and skills in WHM without necessary support functions, having restricted leeway for prioritizing WHM and personal commitments they have outside the enterprise. They must take into account the limitations in their room for manoeuvre while also taking advantage of the external resources that have been committed to help them and the enterprise.

This study has several implications. One implication is that there is a need to develop models and tools for implementing occupational and health regulations that are adapted to SSEs. The second implication is that it is important for SSE managers to obtain more knowledge about WHM and workplace health issues. This can be accomplished by developing local networks dedicated to these issues; research indicates that such networks can be successful if there is trust among the network members (Antonsson et al., Citation2002). Given that there is insufficient cooperation between SSEs and OH, a third implication is that OH consultants can coordinate the networks discussed in this study and support managers in WHM and workplace health processes. It is also important that managers receive support for improving their own working conditions and work–life balance. The final implication is that future research should focus more on tools for WHM and the significance of external factors for SSEs using both qualitative and quantitative methods. In particular, there is a need to determine more about how external factors such as OH, the Social Insurance Agency, boards, and mentors can support SSE managers in WHM and workplace health processes.

Trustworthiness and limitation

The findings should be interpreted with caution both because of the sample size in a single geographical context in Sweden and Norway and because the enterprises participated in a workplace health-promotion project. One limitation might be that the managers had positive attitudes about WHM because they were participating in a project. However, since we asked for managers’ previous experiences before they participated in the project, the intention was to capture their past experiences, not what they experienced because they were positive about participating in the workplace health-promotion project.

Nevertheless, the aim of qualitative research is not to extend findings derived from selected samples to the world at large, but rather to transform and apply them to similar situations in other contexts (Polit & Beck, Citation2004). One strength of this study is its focus on SSEs in different sectors, along with the relatively extensive interviews.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Linda Näsström and Bente Rømo Søreng for their assistance in data collection and/or transcribing interviews. We owe special gratitude to the managers of SSEs in Norway and Sweden who generously shared their experiences with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. An IW enterprise or an “IA business” is a Norwegian term for an enterprise that has entered into a collaboration agreement with the NAV (The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration) for Inclusive Workplace Support.

References

- Abrahamsson, L. (2006). Småföretag – hjältestory, familjeaffär eller ren business. In H. Ylinenpää, B. Johansson, & J. Johansson (Eds.), Ledning i småföretag [Swedish] [Management in small enterprises]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Ahlberg, G., Bergman, P., Ekenvall, L., Parmsund, M., Stoetzer, U., Waldenström, M., & Svartengren, M. (2008). Hälsa och framtid. [Swedish] [Health and future]. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet.

- Almqvist, R., & Henningsson, J. (2009). When capital market actors reduce the complexity of corporate personnel and work environment information. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 13(1), 53–66. doi:10.1108/14013380910948072

- Andersson, I.-M., & Hägg, G. M. (2006). Arbetsmiljöarbete i Sverige 2004. En kunskapssammanställning över strategier, metoder och arbetssätt för arbetsmiljöarbete [Swedish] (Vol. 6) [Working environment issues in Sweden 2004. A review of strategies, methods and approach to working environment issues]. Arbete och Hälsa: Arbetslivsinstitutet.

- Antonsson, A.-B., Birgersdotter, L., & Bornberger-Dankvardt, S. (2002). Small enterprises in Sweden. Health and safety and the significance of intermediaries in preventive health and safety. Arbete och Hälsa. (1), (Work and Health 2002:1). Stockholm: National Institute for Working Life.

- Bornberger-Dankvardt, S., Ohlson, C.-G., & Westerholm, P. (2003). Arbetsmiljö- och hälsoarbete i småföretag – försök till helhetsbild. [Swedish] [Working environment and healthy work in small enterprises – an attempt to an overall picture]. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet (Arbetsliv i omvandling 2003:1).

- Breslin, F. C., Kyle, N., Bigelow, P., Irvin, E., Morassaei, S., MacEachen, E., … Amick III, B. C. (2010). Effectiveness of health and safety in small enterprises: A systematic review of quantitative evaluations of interventions. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20, 163–179. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9212-1

- Breucker, G. (2001). Small, healthy and competitive. New strategies for improved health in small and medium-sized enterprises (Report on the Current Status of Workplace Health Promotion in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)). Essen: Federal Association of Company Health Insurance Funds.

- Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory, objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 509-535)). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Chu, C., Breucker, G., Harris, N., Stitzel, A., Gan, X., Gu, X., & Dwyer, S. (2000). Health promoting workplaces – international settings development. Health Promotion International, 15(2), 155–167. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.2.155

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cunningham, T. R., Sinclair, R., & Schulte, P. (2014). Better understanding the small business construct to advance research on delivering workplace health and safety. Small Enterprise Research, 21(2), 148–160. doi:10.1080/13215906.2014.11082084

- Dellve, L., Skagert, K., & Vilhelmsson, R. (2007). Leadership in workplace health promotion projects: 1- and 2-year effects on long-term work attendance. European Journal of Public Health, 17(5), 471–476. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckm004

- Denzin, N. K. (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative Research, 1(1), 23–46. doi:10.1177/146879410100100102

- Department of Health. (2004). Choosing health: Making healthier choices easier (The Wanless Report, 16). London: TSO.

- Eakin, J. M., Lamm, F., & Limborg, H. J. (2000). International perspective on the promotion of health and safety in small workplaces. In K. Frick, P. L. Jensen, M. Quinlan, & T. Wilhagen (Eds.), Systematic occupational health and safety management (pp. 227–247). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Eriksson, A. (2011). Health-Promoting Leadership: A study of the concept and critical conditions for implementation and evaluation ( Thesis). Nordic School of Public Health, Gothenburg.

- EU. (2003). OJL (Official Journal of the European Union). L124/37-41. Retrieved from http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/oj/

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2013a). Promoting health and safety in European Small and Medium-sized Enterprises. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2013b). Safety and health in micro and small enterprises. Retrieved from https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/safety-and-health-micro-and-small-enterprises.

- European Network for Workplace Health Promotion. (2001, June). The Lisbon statement on workplace health in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Adopted in Lisbon, Portugal.

- Frick, K., Langaa Jensen, P., Quinlan, M., & Wilthagen, T. (Eds.). (2000). Systematic occupational health and safety management. Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Frick, K., & Zwetsloot, G. I. J. M. (2007). From safety management to corporate citizenship: An overview of approaches to managing health. In U. Johansson, G. Ahonen, & R. Roslender (Eds.), Work health and management control (pp. 9–134). Stockholm: Thomson Fakta.

- Gjerstad, P., & Lysberg, F. (2012). Leadership and health promotion workplaces. In S. T. Innstrand (Ed.), Health promotion – theory and practice, research centre for health promotion and resources. Trondheim: HiST/NTNU.

- Grawitch, M. J., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129–147. doi:10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129

- Griffin, B. L., Hall, N., & Watson, N. (2005). Health at work in small and medium sized enterprises. Issues of engagement. Health Education, 105(2), 126–141. doi:10.1108/09654280510584571

- Gunnarsson, K. (2010). Entrepreneurs and small-scale enterprises. Self-reported health, work conditions, work environment management and occupational health services ( Thesis 574). Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Gunnarsson, K., Andersson, I.-M., & Josephson, M. (2011). Swedish entrepreneurs’ use of occupational health services. Workplace Health & Safety, 59, 437–445.

- Gunnarsson, K., Vingård, E., & Josephson, M. (2007). Self rated health and working conditions of small-scale enterprisers in Sweden. Industrial Health, 45, 775–780.

- Hasle, P., & Limborg, H. J. (2006). A review of the literature on preventive occupational health and safety activities in small enterprises. Industrial Health, 44, 6–12.

- Hasle, P., Limborg, H. J., Kallehave, T., Klitgaard, C., & Rye Andersen, T. (2012). The working environment in small firms: Responses from owner-managers. International Small Business Journal, 30(6), 622–639. doi:10.1177/0266242610391323

- Hasle, P., Limborg, H. J., & Nielsen, K. T. (2014). Working environment interventions ? Bridging the gap between policy instruments and practice. Safety Science, 68, 73–80. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2014.02.014

- Holt, M., & Powell, S. (2015). Health and well-being in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). What public health support do SMEs really need? Perspectives in Public Health, 135(1), 49–55. doi:10.1177/1757913914521157

- Jiménez, P., Winkler, B., & Dunkl, A. (2016). Creating a healthy working environment with leadership: The concept of health-promoting leadership. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–19. doi:10.1080/09585192.2015.1137609

- Landstad, B. J., Hedlund, M., & Vinberg, S. (2017). How managers of small-scale enterprises can create a health promoting corporate culture. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 10(3), 228–248. doi:10.1108/IJWHM-07-2016-0047

- Larsson, J., & Vinberg, S. (2010). Leadership behaviour in successful organisations: Universal or situation-dependent? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 21, 317–334. doi:10.1080/14783360903561779

- Limborg, H. J., & Grøn, S. (2014). Networks as a policy instrument for smaller companies. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 4(3), 53–55. doi:10.19154/njwls.v4i3.4179

- Lindström, K., Schrey, K., Ahonen, G., & Kaleva, S. (2000). The effects of promoting Organizational health on worker well-being and organizational effectiveness in small and medium-sized enterprises. In L. R. Murphy & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Healthy and Productive work – an international Perspective. London: Taylor & Francis.

- MacEachen, E., Kosny, A., Scott-Dixon, K., Facey, M., Chambers, L., Breslin, C., … Mahood, Q. (2010). Workplace health understandings and processes in small businesses: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. J Occup Rehabil, 20, 180–198. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9227-7

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing Qualitative Research. 4th edition. London: Sage.

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching. London: Sage.

- Meggeneder, O. (2007). Style of management and the relevance for workplace health promotion in small and medium sized enterprises. Journal of Public Health, 15, 101–107. doi:10.1007/s10389-006-0088-7

- Moen, B. E., Hanoa, R. O., Lie, A., & Larsen, Ø. (2015). Duties performed by occupational physicians in Norway. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England), 65, 139–142. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqu184

- Moser, M., & Karlqvist, L. (2004). Small and medium sized enterprises. A literature review of workplace health promotion (Arbetslivsrapport 17 [Working life report]). Stockholm: National Institute for Working Life.

- Nordenmark, M., Vinberg, S., & Strandh, M. (2012). Job control and demands, work life balance and wellbeing among self-employed men and women in Europe. Vulnerable Groups & Inclusion, 3, doi:10.3402/vgi.v3i0.18896.

- The Norwegian Working Environment Act. (2015). Lov om arbeidsmiljø, arbeidstid og stillingsvern mv. [Norwegian] [Act of working environment, working hours and job protection etc.], Oslo: Norway]. (Arbeidsmiljøloven), LOV-2015-12-18-104.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oak, CA: Sage Publication.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research : principles and methods. 7th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Rootman, M., Goodstadt, B., Hyndman, D., McQueen, L., Potvin, J., & Springett, E. Z. (2001). Evaluation in health promotion: Principles and perspectives. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Publications. European Series, No 92.

- Schmidt, L., Sjöström, J., & Antonsson, A.-B. (2011). Vägar till framgångsrikt samarbete med företagshäslovård [Swedish] [Break fresh ground to successful cooperation with occupational health services]. Stockholm: IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet AB.

- SFS 2003:460. (2005). Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. [Swedish] [Swedish Law in Force]. Retrieved from http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/Dokument-Lagar/Lagar/Svenskforfattningssamling/Lag-2003460-om_etikprovning_sfs-2003-460/.

- Skarholt, K., Blix, E. H., Sandsund, M., & Andersen, T. K. (2015). Health promoting leadership practices in four Norwegian industries. Health Promotion International, 31(4), 936–945.

- Sparling, P. B. (2010). Worksite health promotion: Principles, resources, and challenges. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(1). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0048.htm

- Statistics Norway. (2014). Antall virksomheter etter størrelse [Norwegian] [Number of establishments by size]. Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/virksomheter-foretak-og-regnskap/statistikker/bedrifter/aar/.

- Statistics Sweden. (2011). Aktuell statistik ur företagsregistret [Swedish] [Current statistics from the establishment register]. Retrieved from http://www.scb.se/sv_/Vara-tjanster/Foretagsregistret/Aktuell-statistik-ur-Foretagsregistret/.

- Stephan, U., & Roesler, U. (2010). Health of entrepreneurs versus employees in a national representative sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 717–738. doi:10.1348/096317909X472067

- Street, C., & Cameron, A.-F. (2007). External relationships and the small business: A review of small business alliance and network research. Journal of Small Business Management, 45(2), 239–266. doi:10.1111/jsbm.2007.45.issue-2

- Sverke, M. (2009). The importance of the psychosocial work environment for employee well-being and work motivation. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 35, 241–243. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1336

- The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate [Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring]. (2012). Arbetsgivare i små företag. En intervjustudie om deras erfarenheter av sjukskrivningsprocessen. [Swedish] [Managers in small enterprises. An interview study of their experiences of the sick leave process]. Stockholm: Inspektionen för Socialförsäkring.

- The Swedish Working Environment Act. (2014). Arbetsmiljölag [Working environment law], SFS nr [Swedish] (pp. 659). Stockholm: The Swedish Work Environment Authority.

- Tappura, S., Syvänen, S., & Saarela, K.-L. (2014). Challenges and needs for support in managing occupational health and safety from managers’ viewpoints. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 4(3), 31–51. doi:10.19154/njwls.v4i3.4178

- Tjora, A. (2012). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis [Norwegian] [Practising Qualitative methods] (2nd ed.). Oslo: Gyldendal Akademiske.

- Torp, S., Eklund, L., & Thorpenberg, S. (2011). Research on workplace health promotion in the Nordic countries: A literature review, 1986–2008. Global Health Promotion, 18(3), 15–22. doi:10.1177/1757975911412401

- Torp, S., & Moen, B. E. (2006). The effects of occupational health and safety management on work environment and health: A prospective study. Applied Ergonomics, 37(6), 775–783. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2005.11.005

- Vinberg, S. (2006). Health and performance in small enterprises: Studies of organizational determinants and change strategy ( Thesis). Luleå: Luleå tekniska universitet.

- WHO (World Health Organization). (1986). Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Whysall, Z., Haslam, C., & Haslam, R. (2006). Implementing health and safety interventions in the workplace: An exploratory study. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 36(9), 809–818. doi:10.1016/j.ergon.2006.06.007

- Witt, L. B., Olsen, D., & Ablah, E. (2013). Motivating factors for small and midsized businesses to implement worksite health promotion. Health Promotion Practice, 14(6), 876–884. doi:10.1177/1524839912472504