Abstract

This article considers the contributions made to UK comic performance history by women serio-comic performers on the late-nineteenth century British music hall. These women were associated with gritty and witty portrayals of the lives of lower-class Victorians and frequently engaged in ironic representations of ‘acceptable’ versions of female behaviour in performances combining the serious and the comic. Reflecting on the style and content of their characterisations and their direct interactions with audiences, the article examines the varied nature of these largely forgotten acts, and considers the echoes of such serio-comic approaches in contemporary comedy.

Introduction: serio-comic definitions

‘Serio-comic’ is no longer a term familiar to comedy audiences as a description of either performers or their performances, but in the mid-late nineteenth century it was applied to large numbers of women appearing on the UK music-hall stage.Footnote1 Due to the sheer number and diversity of acts described as serio-comic in the second half of the nineteenth century, settling on a single definition is problematic.Footnote2 The most straightforward explanation – the inclusion of comic and serious material in a music-hall performer’s ‘turn’ – though a fair description of some acts, offers only a partial picture of the evolution of the term’s usage. Here, the focus is on those acts which made use of a mixture of comedy and pathos, or even tragedy, not just within the same performance, but as part of specific comic characterisations or songs. In these performances, the ‘serio’ elements were not separated from the comic, and were often intrinsic to the kind of comedy women were creating. Analysis of this material is usefully informed by an interpretation of the serio-comic as ‘mock serious’, implying as it does the use of performed irony, i.e. the presentation of the serious as comic, or vice versa.Footnote3

Reviving acts which predate audio and film recordings as live performance events is no small challenge for the comedy historian. Accounts of performances from this period are frustratingly scant and descriptions of performances by women tend to detail their appearances and costumes at least as often as their jokes. However, viewed alongside surviving lyrics, reviews, interviews and autobiographies can usefully point to how women treated serious issues as comedy; how they made use of the inherent ambiguities of performed irony to avoid censorship; and how they connected with audiences who were perhaps more accustomed than those in the mid-twentieth century to accepting hazy boundaries between popular representations of comic and tragic experience.

Prior to the 1850s, serio-comic appeared in theatrical publicity, advertisements and press reviews, to describe plays, sketches and acts and, in the middle of that decade, women and some men (though considerably fewer) were billed as serio-comic vocalists. The consistent use of the soubriquet grew with the establishment of music hall, and it was soon associated exclusively with women, as the first big serio-comic stars of the halls such as Kate Harley and Louie Sherrington ‘The Cleopatra of Comedy’ emerged. (The Era, January 6th 1867, 4)

Funny and disturbing

Two serio-comic artists who began their careers in the 1860s, the legendary Jenny Hill (1848–1896) and her less well-known contemporary, (1843–1899), were noted for their highly-skilled character studies depicting the very poorest Victorian women, and their work was billed and reviewed as both serio-comedy and ‘low comedy’.Footnote4 Such commentary on the social conditions of the Victorian poor provides rare insight into the lives, opinions and problems of working-class women. Many music-hall artists of this generation had grown up in poverty themselves and were trusted by audiences who recognised their comic interpretations of working-class experience as rooted in credible documentary observation.

Ada Lundberg as her hugely popular maid of all work character in Tooraladdie, complete with boot polish on her face. (from her obituary in The Era, 1899).

Hill was equally celebrated for her faithful portrayals of tragic and humourous characters and her act contained comic and serious songs, and those that combined the comic with the serious. She was also known for performing high-octane dances and physical parodies as part of her sketches and songs. Her interpretation of Dion Boucicault’s popular 1860 melodrama, The Colleen Bawn, for example, climaxed with a comic rendering of the story’s heroine being pushed off a cliff, as Hill leapt from a kitchen table into a bathtub of water (Bratton Citation1986, 108). Hill was committed to constructing believable characters and she engaged in meticulous research and preparation before performing a new character. As Louise Wingrove notes, she was ‘a social observer’ who wanted ‘to depict an accurate, not caricatured’ picture of working women (Wingrove Citation2020, 216–217). Hill herself remarked that in London, East End audiences would not tolerate patronising or mocking depictions of working-class characters. While West End audiences might appreciate them, she noted that when she appeared at venues in poorer districts such songs much be sung ‘without exaggeration or satire’ or she ran the risk of causing offence. Any indication that she was ‘poking fun’ and ‘I should hear shouts of ‘That’s enough, Jenny!’ ‘Chuck it, Jenny!’ (The Pall Mall Gazette, April 13th Citation1892, 1).

Ada Lundberg was advertised as ‘The Daughter of Momus’ and ‘The People’s own Grotesque Artiste, the most Eccentric Lady Comedienne on the Stage’ (The Era, July 25th 1875, 16). Her most popular song, Tooraladdie, which she performed for nearly 20 years – often as an encore demanded by fans – was a study of a ‘smutty faced’, broken-hearted, maid-of-all-work, ‘with her red hair knotted with rags’Footnote5 (Lundberg’s obituary: The Era October 7th 1899, 19). Lundberg combined the pathos and drudgery of her character’s poverty with what commentators agreed was a highly-accomplished, physically grotesque comic portrayal, as her character over-shared with the audience; drunkenly singing about her lost love – a policeman – while polishing a pair of boots. Her audiences laughed at and with this character; sympathising with her difficult life and the pain of her abandonment which Lundberg intermittently punctured with comic relief in a performance that was, according to one reviewer, ‘extravagantly odd’ (The Era, April 30 1887, 16). Henry George Hibbert recalled how the character ‘polished a boot and her nose alternately’ as she sobbed her way forlornly through her song. Audiences evidently appreciated the interweaving of mock-tragedy and the grotesquely comic, but some middle-class critics were discomforted by the characterisation. Though they had to admit it was ‘of marked power’ and ‘exceedingly funny’ (The Era, September 13th 1884, 7), it was, nonetheless, ‘by no means pleasant to contemplate’. (The Era, March 27th 1886, 10). The writer of this last review was so appalled by Lundberg’s portrayal of her character’s excessive drunkenness that he implored her to stop allowing herself to be carried off the stage (ibid.). Less squeamish fans of such unflinching snapshots of the lives of the poor used them to argue in favour of the authenticity of music-hall entertainment against its detractors. According to one defender of the halls writing in 1892, Lundberg’s performance style alone was ‘enough to show the possibilities of the serio-comic’ (Pall Mall Gazette April 13th 1892, 1).

‘Gagging’ and ‘archness’

Frequently criticised for their performances, even before they stepped on stage, serio-comics seemed to embody late nineteenth-century perceptions of female performers as either vulgar and coarse, like Hill and Lundberg, due to their lower class portrayals, or as morally suspect, or at risk of becoming so due to the dubious nocturnal and independent nature of their work.Footnote6 They were often singled out for reproach, and the term soon acquired a stigma which at best suggested moral ambiguity; at worst, direct associations with prostitution. Their treatment in the press and by the censor, which took the form of the inspectorate of the London County Council’s Theatre & Music Halls Committee, is indicative of attitudes to women generally, to women performers specifically and, most particularly, to those who asserted their female voices through unflinching and sharp-witted exchanges with audience members and comic material about women’s hardships, faults and pleasures. The serio-comic style became synonymous with modes of delivery reviewers described as ‘arch’ or ‘fast’ and included frank and ‘slangy dialogues’ with audiences. It was through these dialogues, delivered in between character-based songs and littered with contemporaneous idioms and colloquialisms, that performers engaged in semi-improvised interactions with audiences which pre-empted modern stand-up techniques. In the Victorian context, this practice was known as ‘gagging’ and its appeal and perils were regularly debated in the popular press. Unsurprisingly, key to most objections was the potential risk to decency posed by gagging, allowing as it did a degree of unfettered, spontaneous, public joking with which the censor simply could not trust music hall’s mixed (gender and class) popular audiences.Footnote7

Bessie Bellwood (1856–1896) was the epitome of the defiantly working-class performance style of most concern to music-hall detractors and would-be reformers of their programmes. The intimate relationship she cultivated with her loyal fans over decades has echoes in contemporary stand-up practice, she had a reputation for direct and often aggressive ‘gagging’ and was renowned for her ability to deal with hecklers. Music-hall songwriter, Richard Morton, recalled one performance in which she acknowledged an audience member occupying a box, who was clearly enjoying her act:

‘Don’t open your mouth so wide. You’ll cut your throat with your collar’. The result was a louder guffaw than before. ‘That’s wider. Now I can see what you had for your dinner’. (The Era, April 1 1914, 19)

Bellwood was frequently criticised for her confrontational style and always vociferously defended her reputation, suing one magistrate for libel when he claimed she had been dismissed from more than one engagement on the strength of complaints about innuendo and indecency (Beale Citation2020, 103).

During this period, it was commonplace for women known for predominantly or entirely comic acts to be billed as serio-comics, serio-comediennes or simply ‘serios’. , undoubtedly the best remembered of all music-hall women, was described as a serio-comic – indeed, as ‘The Queen of Serio-Comedy’ – at a time in the late 1890s when there were no serious elements in her act. For most of her four-decade career, her brand of serio-comic performance adhered to the ‘mock serious’ definition. She made frequent use of performed irony and ‘archness of expression’ which enabled her to, for the most part, evade the censor in celebratory performances recounting tales of women’s sexuality, sexual attraction and romantic adventures that were famously laden with comic innuendo.

By the end of the 1880s, the profession was considered – even by insiders – to be ‘over-run with what are called ‘serio-comics’.Footnote8 According to performer , interviewed in 1887, so many British serios were appearing on the popular US stage in 1885 that they were given the nickname ‘chronics’ (The Era, April 30th 1887, 16). In the late 1890s, the serio of the earlier halls was parodied as an old-fashioned, lower-class cliché, even by those who had previously been advertised as such.Footnote9 This shift in perceptions mirrors the evolution of music hall from its mid-century local, working-class origins into the behemoth of ‘respectable’ mass entertainment it had become by the century’s end.

Ironic disruptions

Lyrics of serio-comic songs and accounts of performances of them offer glimpses into every stage of a lower-class woman’s life and contemporaneous ideas about her. Most songs were written by men, although established performers earning a regular wage commissioned songs to match their particular performance styles, and sometimes collaborated with their favourite songwriters to develop new material.Footnote10 Regardless of who wrote a song, its unabridged comic meanings became fully apparent only in performance, as the serio-comic embodied the lyrics and foregrounded the attitudes of her characters and many women in her audiences. Furthermore, as she spoke directly to her audiences, her own voice as performer provided a counterpoint to the characters she portrayed, and frequently contributed ironic commentary on the presumed attitudes and aspirations of Victorian women. I am not claiming these popular representations as self-consciously feminist but, through their serio-comic approaches, these performers regularly engaged in accidental feminisms; forming deliberately ironic relationships with their material and stretching possible perceptions of womanhood and female behaviour.

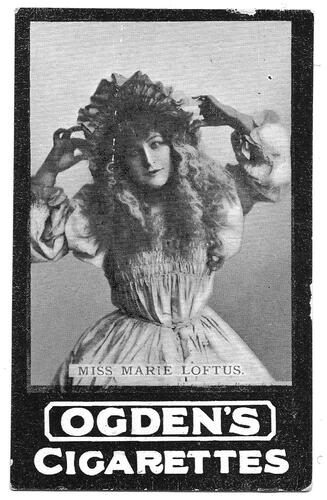

Some comic treatments of female stereotypes were lyrically explicit in their ironic approaches to ideals of women and womanhood. Marie Loftus’ (1857–1940) gloriously indifferent portrayal of a wife and mother in A Comfort and a Blessing to a Man (Dodsworth Citation1888), for example, creates an ironic reversal of everything her audiences know about the ‘natural’ role of the Victorian woman. The wife in this narrative song is far removed from the tyrannical perfection of Coventry Patmore’s famously steadfast and uncomplaining ‘angel in the house’, and the intended irony of the song’s title becomes crystal clear as the story unfolds.Footnote11 Loftus’ character is completely, hilariously – or perhaps terrifyingly for some in her audiences – undomesticated; leaving the childcare and housework to her husband and loudly berating him when he rolls in drunk late at night. Finally, she fails so entirely to nurse him when he is ill that:

This character distorts the sentimental image of the wife who accepts her lot however unfairly she is treated, instead revealing all at once the flaws in the illusion of the ideal woman, the idiosyncratic voice of her exaggerated subversion of this image, and, crucially, the gap between the two, which is occupied by the majority of women in her audiences.

The potential of serio-comic material to nightly invite audiences to re-imagine acceptable roles and behaviour for women frequently depended on performers’ abilities to shift register during their performances. As comedians continue to do, they reflected back at their audiences key social and philosophical debates, challenges and attitudes of the day; finding comic exaggerations and extensions to highlight topical absurdities and stereotypes. In Going to be Married in the Morning (Conley Citation1898) Lily Marney’s grotesque caricature of a stereotypical spinster comically addresses one such concern of the era: ‘The Surplus Woman Question’.Footnote12 Marney’s character is so desperate to marry that she invites home ‘for tea’ a man she meets in the park, kidnaps him, and then invites the audience to their wedding:

This character embodies women’s presumed terror of remaining single – driven predominantly by the grotesquely gendered wage differentials of the era, and the attendant profound social stigma attached to being a woman alone and unable to support yourself. The extremity of her performance of this unmanageable and disturbingly unfeminine woman brings into comic question perceptions of single women, as she engages in what Rosie White has termed performing gender ‘as problematic’ (White Citation2016, 308). This spinster is a laughing stock, but her plight is transformed through performed ironic exaggeration into social commentary about the situation she finds herself in, and the social pressures that have brought her there. The absurd excess of Marney’s ‘failed copy’ of womanhood as she goes to such unacceptably desperate lengths to adhere to the acceptable norm, both highlights and disrupts the stereotype (Butler Citation1990, 138–139).

Comic consolations

Other serio-comic performances provided a public forum for shared experiences and problems, drawing on music hall’s ‘culture of consolation’ (Stedman Jones Citation1982, 117). These songs were expressions of how women felt about the choices – or lack of them – afforded by their private and public positions, in songs sharing complaints about their husbands, families, work and local communities; a form of comic blues.Footnote13 Many of these women were outspoken and defiant, despite their hardships. For example, Katie Lawrence’s (1868–1913) Lizer ‘Awkins (Morris and Le BrunnCitation1892) observes:

In Citation1893, (1873–1951) performed a ‘ladies’ answer’ to Albert Chevalier’s famously sentimental song My Old Dutch in which he sings of his wife (Chevalier and Ingle Citation1892): ‘We’ve been together now for forty years/An’ it don’t seem a day too much’. In Victoria’s version, My Old Man, she offers a wife’s view: ‘though we’ve been married only one short year, it seems much more like nine’. Whereas Chevalier would not swap his ‘Sal’ for any ‘lady livin’ in the land’, Victoria wryly observes that ‘there’s not a donah down our court as would swap her own for mine’.Footnote14 The serio-comic approach does not avoid the inevitability of life but acknowledges and often rails against it. As music-hall’s upbeat take on the world demands, however, resignation to grim realities regularly gives way to optimism, or at least to celebratory stoicism, for example, in the form of the joyful physical abandon and skillfully wild dances of the sort Hill, Lundberg and Victoria were famous for.

Vesta Victoria posing for a cigarette card issued by Kinney Brother’s Tobacco for Sweet Caporal cigarettes, 1890. (author’s collection).

Serio-comic victims and butts

These first-person stories frequently included a generous dose of self-criticism, acknowledging their characters’ poor judgement or foolish decisions as a result of gullibility or ignorance. This approach is akin to what Paul McDonald has dubbed ‘redemptive self-mockery’ (McDonald Citation2010, 131). Many of Victoria’s characterisations ensured her women were not simply the suffering victims of their circumstances but that audiences could identify with their ‘shortcomings and recognise them as their own’ (McDonald Citation2010, 87). She created a very popular series of self-deprecatory characters who are apparently both the victims and the butts of her jokes. The music-hall classic, Waiting at the Church (Leigh and Pether Citation1906), for example, tells the story of a woman misled, defrauded and jilted at the altar by a man who is already married. Victoria’s performance of this piece (for which she wore a wedding dress, ritualising the character’s humiliation), provides a comic warning to women in her audiences not to be so gullible in their romantic choices, and they would certainly not wish to be associated with the behaviour of this laughably hapless character. This image is, however, overlaid with another – of Victoria the performer and admired celebrity, whose public identity undoubtedly leavened audience reception of her act. Even when playing easily deceived or entirely pathetic characters, the serio-comic was not merely a passive female spectacle. The audience colluded with her through their acceptance of her fictional characterisation but her own comic voice and presence gave her a personality beyond what Linda Mizejewski calls ‘performing pretty for male appreciation’, or playing within a fixed range of female types (Mizejewski Citation2014, 30).Footnote15

A later song performed by Victoria, A Baby with Men’s Ways (Leigh and Pether Citation1904), is a less overtly funny, disturbingly ironic representation of coercive control and physical abuse which reflects the acceptance of a certain level of violence within marriage during this period.Footnote16 Victoria paid great attention to the detail of her portrayal and appeared in tattered clothing, grotesquely made up with bruises. At first this character seems to be entirely in denial about her situation. However, unlike Waiting at the Church, there are moments in the pathos of this lyric which indicate that Victoria’s performed acknowledgement of the character’s tragedy might cut through her self-deception and allow the audience to share her bitter joke:

As Victoria’s character vividly catalogued the abuse she suffered in the other verses of this song, her ironic attitude doubtless rang true for many women in her audiences for whom the music hall was likely the only context in which their experiences were publicly aired. This is uncomfortable material, and its blurring of the ethical line between who or what is the victim and/or the butt of a joke, has echoes in the twenty-first century. For example, in Heather Jordan Ross’ stand-up performance as part of the Rape Is Real and Everywhere comedy tour by rape survivors (launched in 2016), she tells the audience:

Someone tried to rape me in high school and he had me pinned down, really big guy, and I was saying no, and I was like ‘omg, he can’t hear me saying no…his poor ears’. (Jordan Ross Citation2017)

As Melanie Proulx observes, ‘even though Ross pokes fun at herself, she does so for being the product of rape culture and thus laughs at rape culture too’ (Proulx Citation2018, 194). Victoria’s serio-comic performance is similarly mocking her character’s denial of the reality of her situation and the culture of silence surrounding it, which ignores and tolerates abuse, and makes it taboo for her to discuss it.

The serio-comic legacy

The serio-comic conventions and approaches established on the halls extended into early twentieth-century variety acts long after the term was out of fashion, as women continued to create material about their daily miseries and challenges and defied the status quo through comic gender transgressions. Daisy Dormer’s (1883–1947) I’ve Been Dreaming (Collins Citation1909), preserved the pith and pathos of the serio-comic’s treatment of marriage as a catastrophe for women:

Maidie Scott’s (1881/2–1966) irresistibly plaintiff 1912 recording of Edna Williams’ song If the Wind Had Only Blown the Other Way (Citation1909), recounts a woman’s despondency that she ended up married with children. Scott delivers each line of this proto-feminist, anti-marriage and anti-motherhood song with impeccable diction in a delicately mournful tone, perfectly counterpointing the increasingly biting lyrics:

In an ongoing contemporary shift away from the mid-twentieth century tendency to silo popular comedy as ‘light’ – a trivial escape from daily woes – there is growing interest across the comedy landscape in using humour as means to lean directly into more challenging aspects of lived experience. Usefully contributing to evolving definitions of the possibilities of this ‘blurring the boundaries between comic and serious discourse’, Kate Fox has coined the word ‘humitas’: an etymological ‘blend of “humour and “gravitas”’, describing ‘weighty humour or fluid seriousness’, which ‘enjoys incongruity and paradox and doesn’t draw a clear line between satire and sincerity’ (Fox Citation2017).

Stand-up comedians have, of course, tackled serious ideas and issues as part of their acts for decades, but this more recent serio-comic turn sees performers examining sometimes extremely challenging personal experiences through a comic lens, in setup/punchline-busting comedy acts and hybrid performances mixing stand-up techniques with other performance practices including performance art, storytelling, poetry, music and theatre.

Like the serio-comics on the music hall, often these performers shift registers – from the comic to the serious and back again – as they help audiences navigate their uncertain emotions and responses to this material as comedy. Tig Notaro’s now legendary 2012 performance at Largo in Los Angeles is a useful example here. At a gig shortly after her breast cancer diagnosis, Notaro disclosed her still raw responses to the news with her trademark light-touch, deadpan delivery, giving her audience permission to laugh; not at her diagnosis, but at her bewilderment and their own guilt and uncertainty about laughing. In the audio recording of this performance, she teasingly consoles audience members who vocalise their sympathy and discomfort, leaving them unsure if she is joking or serious, or both. In a process Sophie Quirk describes as ‘packaging’ (Quirk Citation2015, 94–98), from the very start of the set, Notaro disorientates the audience with familiar stand-up framing, timing and delivery. So, they are laughing before they notice the gravity of what they have laughed at, and then laugh again, at themselves, for laughing:

Hello… [Cheers and applause]. Good evening. Hello. I have cancer.

[laugher] How are you?…Hi. How are you? Is everybody having a good

time? ‘I have cancer’. How are you? [Laughter]. (Notaro 2012/Citation2013)

In an example with multiple music-hall echoes – as it is both character comedy and male impersonation – Natalie Palamides’ Nate (2016–2020), explores complex questions about rape and sexual consent in sometimes excruciatingly awkward ways for the audience members she interacts with. She embodies Nate –her female body barely disguised with clearly fake chest hair – as ineptly, desperately masculine, flawed but likeable, ignorant but trying hard to understand how to be better. In doing so, she overlays his character with her own commentary and so demands that, while laughing, audiences reflect on their own responses and attitudes to these issues.

Serio-comic discourse acknowledges the humitas of life’s impossible contradictions and, rather than being incongruous, this rings true for contemporary audiences. Significantly, it also embraces ethical approaches to jokes about personal suffering and tragedy. For comedian Cait Hogan, the parameters of such an approach are clear: ‘It must separate the suffering from the absurdity’ (Hogan Citation2020, 282). As the sporadic debate continues about when, how, or if cancel culture may trigger live comedy’s endgame, performers are getting on with the business of making people laugh in acts which recognise that, simply put, the actual victims of abuse, trauma and suffering can no longer be the comic victims and/or butts of jokes about abuse, trauma and suffering. Instead, what MacDonald calls ‘laughter bonds’ are being created through ‘recognition and empathy, as opposed to superiority and mockery’ (2010, 87), in comedy which gives voice to victims and survivors as they explore and share with audiences the humour they have found in the most devastating truths about their experiences.

Reflecting their context, serio-comic approaches on the music hall did not draw sensitive distinctions between comic victims and butts. Frequently, broad, mocking stereotypes were staples of the form and everyone was fair game for criticism and comic attack. However, as the examples considered above reveal these performers also offered the solace of shared experience. Sometimes their acts included proactive messages, urging women in their audiences to stand up for themselves rather than accepting the unacceptable, admonishing them for their poor choices, or encouraging them to recognise and celebrate the opportunities offered by women’s changing status and their ‘widening sphere’.Footnote17 Through their characters’ stories and the relationships they formed with their audiences, the serio-comics embraced pathos and hardship, encouraging collective laughter at attitudes that were sometimes grotesquely stoic, sometimes defiantly bitter, sometimes self-deprecating or consolatory. Such approaches provided audiences with comic release, but they also offered alternative ways of looking at and laughing at the darkest realities of their lives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sam Beale

Sam Beale is Senior Lecturer in Theatre Arts at Middlesex University, London, specialising in stand-up comedy, solo performance and autobiographical performance. Over the last 20 years, she has regularly collaborated as a writer, director and workshop facilitator with comedians, theatre companies and community groups. She researches and writes about the history and practice of comedy and performance and is the author of The Comedy and Legacy of Music-Hall Women 1880–1920: Brazen Impudence and Boisterous Vulgarity (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Notes

1 In 1878 The Era Almanack listed 384 women working as serio-comics; 357 were listed as ‘male comic singers’ (Ledger 1878).

2 See Beale (2020, 16–18 and 51–52) on the evolution and multiple definitions of the term.

3 Webster’s Dictionary, Citation1961 (Babcock Gove), offers ‘having a mixture of seriousness and sport’ and ‘Mock serious [a – vocalist]’. The OED online, 2016 suggests that the serio-comic: ‘mixes the comic and the serious, esp. by presenting a comic plot, situation, etc., in a serious manner, or vice versa’.

4 There is a discrepancy in the historic record of Lundberg’s birth date. Her obituary states 1850. Birth records indicate 1843 (Beale Citation2020, 62).

5 No lyrics of this song have survived, almost certainly because it was of an unsuitable tone and subject for renditions in middle-class drawing rooms and so was never reproduced in printed form.

6 See The Observer, August 4th 1862 for an early attack on the trend for women described serio-comics, and the story of Miss Tottie Tartington, a morality tale about a serio-comic in McGlennon’s Star Songbook, Citation1888. No. 4.

7 See Beale (2020, Chapter 3), ‘I must tell you this: Intimacy, Gagging and Comic Licence in Performer-Audience Relationships’ for a history of music-hall gagging.

8 Nellie L’Estrange, in an interview ‘Music Hall Stars, and how they became so. By themselves’ McGlennon’s Star Songbook, No. 4 June Citation1888, 2.

9 The Era, November 13, 1897, 18, describes a performance by Marie Loftus in which she receives an ‘uproarious reception’ for ‘her burlesque of the tenth-rate serio of bygone days’.

10 For example, Marie Lloyd recalled developing the idea for her breakthrough song Wink the Other Eye with her good friend George Le Brunn (The Sketch, December 26th 1894, p. 7); Bessie Bellwood is credited as writing her huge 1885 hit, What Cheer ‘Ria, with Will Herbert. Nellie Wallace wrote a number of her most successful songs.

11 Coventry Patmore’s influential narrative poem, The Angel in the House, idealising his wife, Emily, after her death, was written in parts between 1854 and 1862.

12 The 1851, 1861 and 1871 censuses in England and Wales concluded that the majority of adults were women and that marriage rates were falling. This resulted in a press-induced panic dubbed the ‘Surplus Woman Question’ or simply the ‘Woman Question’.

13 Carole Morley (in Fryer Citation2012, p. 205) considers Victoria’s songs about marital unhappiness in relation to US female blues singers.

14 Donah: Nineteenth century street slang for woman or girl.

15 See Susan Glenn (2002, 3) for further consideration of women performers as active and passive spectacles.

16 See D’Cruze (1995, 62) and Lewis (1984, 10) for discussion of attitudes to domestic abuse during this period.

17 A Widening Sphere is the title of Martha Vicinus’ Citation1977 book about women’s changing roles in Victorian Britain.

References

- Babcock Gove, P., ed. 1961. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary. Cambridge: Riverside Press.

- Beale, S. 2020. The Comedy and Legacy of Music-Hall Women 1880-1920: Brazen Impudence and Boisterous Vulgarity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bratton, J. S. 1986. “Jenny Hill: Sex and Sexism in Victorian Music Hall.” In Music Hall: Performance & Style, edited by J. S. Bratton, 92–110. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- D’Cruze, S. 1995. “Women and the Family.” In Women’s History: Britain 1850–1945, edited by J. Purvis, 51–84. London: UCL Press.

- Fox, K. 2017. “Humitas: A New Word for When Humour and Seriousness Combine.” The Conversation, August 24th, 2017.

- Glenn, S. 2002. Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hogan, C. 2020. “The Ethics of “Rape Jokes”.” In The Dark Side of Stand-Up Comedy, edited by P. Oppliger and E. Shouse, 277–292. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jordan Ross, H. 2017. Rape Is Real & Everywhere (Live Tour).

- Ledger, E., ed. 1878. The Era Almanack Dramatic & Musical. (1868-1895). London: HEB Humanities-Ebooks.

- Lewis, J. 1984. Women in England 1870–1950. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- McDonald, P. 2010. Laughing at the Darkness: Postmodernism and Optimism in American Humour (Contemporary American Literature Series). HEB. Humanities-Ebooks.

- McGlennon’s Star Songbook. 1888-1909. No. 4 June 1888, p, 2. London.

- Mizejewski, L. 2014. Pretty/Funny. Women Comedians and Body Politics. Austin: University of Texas.

- Morley, C. 2012. “The Most Artistic Lady Artist on Earth: Vesta Victoria.” In Women in the Arts in the Belle Epoque: Essays on Influential Artists, Writers and Performers, edited by P. Fryer, 186–209. Jefferson: McFarland.

- Notaro, T. 2012/2013. Live. Audio CD. Bloomington: Secretly Canadian.

- Oxford English Dictionary Online OED Online. 2016, March 17 update. https://public.oed.com/updates/

- Palamides, N. 2016-2019. Nate (Live Tour).

- Proulx, M. 2018. “Shameless Comedy: Investigating Shame as an Exposure Effect of Contemporary Sexist and Feminist Rape Jokes.” Comedy Studies 9 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1080/2040610X.2018.1494361.

- Quirk, S. 2015. Why Stand Up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. London: Bloomsbury Methuen.

- Stedman Jones, G. 1982. “Working-Class Culture and Working-Class Politics in London, 1870–1900: Notes on the Remaking of a Working Class.” In Popular Culture: Past and Present, edited by B. Waites, T. Bennett, and G. Martin, 92–121. London: Routledge.

- The Era. 1838–1939. 19th Century British Library Newspapers. London.

- The Pall Mall Gazette. 1892, April 13. The Pall Mall Gazette (1865–1938), 1. London: British Newspaper Archive.

- The Observer. 1862, August 4. As cited in Musician & Music Hall Times, August 9th, 1862, 92–93.

- Vicinus, M. 1977. A Widening Sphere. Changing Roles of Victorian Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- White, R. 2016. “Funny Peculiar: Lucille Ball and the Vaudeville Heritage of Early American Television Comedy.” Social Semiotics 26 (3): 298–310. doi:10.1080/10350330.2015.1134826.

- Wingrove, L. 2020. “‘Sassing; Back’: Victorian Serio-Comediennes and Their Audiences.” In Victorian Comedy & Laughter: Conviviality, Jokes & Dissent, edited by L. Lee. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 207–233.

List of Songs Referenced

- Chevalier, C., and C. Ingle. 1892. My Old Dutch. London: Reynolds & Co.

- Collins, Charles. 1909. I’ve Been Dreaming. London: Francis, Day & Hunter.

- Conley, T. 1898. Going to Be Married in the Morning. McGlennon’s Star Songbook, No. 123. London and Manchester: McGlennon.

- Dodsworth, T. 1888. A Comfort and Blessing to Man. McGlennon’s Star Songbook, No. 6. London and Manchester: McGlennon.

- Leigh, F. W., and H. E. Pether. 1904. A Baby with Men’s Ways. London: Francis, Day & Hunter.

- Leigh, F. W., and H. E. Pether. 1906. Waiting at the Church. London: Francis, Day & Hunter.

- Morris, A. J., and G. Le Brunn. 1892. Lizer’ Awkins. London: Reynolds & Co.

- No author recorded. 1893. My Old Man. No publisher recorded.

- Williams, E, and B. Wynne. 1909/1912. If the Wind Had Only Blown the Other Way. Windyridge CD R16: Mother’s Advice. Nellie Wallace & Maidie Scott. Windyridge Music Hall CDs (musichallcds.co.uk).