Abstract

Socio-interpersonal factors have a strong potential to protect individuals against pathological processing of traumatic events. While perceived social support has emerged as an important protective factor, this effect has not been replicated in people with intellectual disabilities (ID). One reason for this might be that the relevance of socio-interpersonal factors differs in people with ID: Social support may be associated with more stress due to a generally high dependency on sometimes unwanted support. An exploration of the role of posttraumatic, socio-interpersonal factors for people with ID is therefore necessary in order to provide adequate support. The current study aims to explore the subjective perception of social reactions to disclosure of sexual violence in four women with mild to moderate ID. The study was conducted in Austria. The women were interviewed about their perception of received social reactions as benevolent or harmful, their emotional response, and whether they perceived being treated differently due to their ID diagnosis. The interviews were analysed using qualitative content analysis. First, the interviews were coded inductively, and social reactions were then deductively assigned to three categories that were derived from general research: positive reactions, unsupportive acknowledgement, turning against. Findings on the perception of social reactions were in line with findings from the general population. Overall, participants reported that they did not feel that they were treated any differently from persons without disabilities. However, the social reactions they received included unjustified social reactions, such as perpetrators not being held accountable. A possible explanation may be a habituation and internalisation of negative societal attitudes towards women with ID. Empowerment programmes and barrier-free structural support for women with ID following trauma exposure should be improved.

Background

People with intellectual disabilities (ID) have an increased risk of trauma exposure as well as of pathological posttraumatic processing (Catani and Sossalla Citation2015, Mevissen and de Jongh Citation2010, Hughes et al. Citation2012). In the general population, approximately 4% of people who survive trauma exposure develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although this varies significantly according to trauma type, with sexual violence showing the highest conditional probability rates of 19% (Kessler et al. Citation2017). In people with ID, a number of risk factors contribute to an elevated conditional risk of developing PTSD (Mevissen and de Jongh Citation2010). For instance, well-known risk factors such as lower cognitive functioning and a lower developmental level are inherent in the ID population (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). Moreover, socio-interpersonal factors have been shown to impact the conditional probability of developing PTSD (Brewin et al. Citation2000; Ozer et al. Citation2003; Maercker and Horn Citation2013). Given the impairments of people with ID in the socio-interpersonal domain (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013), these factors can be assumed to play a major role in the processing of trauma exposure in such individuals (Focht-New et al. Citation2008). However, the mediating effect of socio-interpersonal factors on the association between trauma exposure and PTSD, which is known from the general population, has not yet been replicated in people with ID (Wigham et al. Citation2014, Hulbert-Williams et al. Citation2011). There are currently no instruments allowing for an adequate and specific assessment of socio-interpersonal factors in the ID population. Therefore, the current study applies a qualitative approach to explore the role of socio-interpersonal factors in people with ID.

The relevance of socio-interpersonal factors in coping with trauma exposure

Almost since the introduction of PTSD in the DSM-III back in 1980 (American Psychiatric Association Citation1980), researchers have been interested in which factors contribute to a successful or pathological processing of traumatic events (Brewin et al. Citation2000, Yehuda and McFarlane Citation1995). A number of significant factors have emerged from this research: Prevailing theories describe PTSD as a disorder of memory, highlighting cognitive function as a key factor in the development and maintenance of its core symptoms (Brewin Citation2014). Moreover, the impact of factors beyond this individual perspective has been found to be crucial, with socio-interpersonal factors, for instance, impacting the development and maintenance of the disorder (Maercker and Horn Citation2013). The latter authors therefore proposed a socio-interpersonal model of PTSD, comprising interpersonal processes that are situated on three levels: an individual, close relationship, and distant social level.

The interpersonal level has received particular scientific attention, with perceived social support emerging as one of the most important protective factors in coping with traumatic events (Brewin et al. Citation2000, Ozer et al. Citation2003). Disclosure is the starting point for gathering and receiving social support and plays a central role in processing trauma (Maercker and Horn Citation2013, Lueger-Schuster et al. Citation2015). Indeed, trauma survivors show an increased need to socially share their experience (Rimé Citation2009) and experimental studies have found that even anonymous, written disclosure exerts therapeutic effects by reducing internal stress (Maercker and Horn Citation2013). However, this positive effect attributed to disclosure is not universal. Disclosure is a complex phenomenon which is influenced by the circumstances in which it happens (Ullman Citation2011). Among a number of factors, the dynamics and outcomes of disclosure depend on the trauma type. It can be assumed that disclosure of sexual violence is unique due to the potential stigma associated with it (Ullman Citation2011) as well as the complex individual social-affective responses (Maercker and Horn Citation2013). Furthermore, the person disclosed to and his or her reaction influence whether disclosure is beneficial (Relyea and Ullman Citation2015, Maercker et al. Citation2016). The survivor’s need to socially share information might be restricted or denied by the recipient for the recipient’s own protection (Rimé Citation2009). Previous research revealed that the type of perceived social reactions following disclosure of sexual violence predicted PTSD symptoms and that perceiving social reactions as harmful can have more negative effects for the survivor than non-disclosure (Ullman Citation2011).

According to Relyea and Ullman (Citation2015), a dichotomous distinction between positive and negative reactions is too simplistic, rendering it necessary to further categorize social reactions. The authors therefore proposed two kinds of negative social reactions to disclosure of sexual violence. The first category, named Turning Against (TA), describes hostile reactions that attack the survivor, comprising reactions such as blaming and stigmatizing the survivor. The second category of reactions, Unsupportive Acknowledgement (UA), subsumes more ambiguous reactions, which are perceived as both healing and hurtful at the same time. This category encompasses reactions such as controlling, distracting, egocentric responses that acknowledge the event but do not provide the survivor with tangible support and coping skills. It was found that reactions of TA led to increased social withdrawal, increased self-blame, and decreased sexual assertiveness. However, depression and PTSD were related more strongly to UA reactions than to TA reactions (Relyea and Ullman Citation2015).

In light of these findings, a closer examination of the association between social reaction types and symptoms of PTSD in people with ID might foster the understanding of the role of socio-interpersonal factors and contribute to a better understanding of risk and protective factors in processing trauma exposure in this population.

Processing of trauma exposure in people with ID

In recent years, the population of people with ID has received increasing attention within trauma research (Mevissen and de Jongh Citation2010, Wigham and Emerson Citation2015, Catani and Sossalla Citation2015). The importance of avoiding a disempowering and non-resilient perspective on people with ID has been pointed out, but also the necessity of recognizing an elevated vulnerability (Wigham and Emerson Citation2015). People with ID are especially susceptible to interpersonal victimisation (Fogden et al. Citation2016). Moreover, women with ID were found to be at a higher risk of sexual abuse than people without ID (Byrne Citation2018). Some inherent characteristics of ID contribute to an elevated vulnerability to pathological processing of traumatic events. For instance, lower cognitive abilities and lower developmental levels have repeatedly emerged as key risk factors for the development of PTSD (Brewin et al. Citation2000). Furthermore, the DSM-5 definition of ID (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013) includes impairments in social skills and, with increasing severity, losses in verbal skills. Thus, it can be assumed that socio-interpersonal risk factors are elevated in people with ID, while at the same time, protective factors are less available.

Given the high relevance of social support in processing trauma exposure, it is surprising that, to the best of our knowledge, only two studies that have explored the mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between trauma exposure and symptoms of trauma sequelae. Surprisingly, neither of these studies found mediating effects (Wigham et al. Citation2014; Hulbert-Williams et al. Citation2011). One possible explanation for this is that social support is often associated with negative aspects in this population (Lunsky and Benson Citation2001). People with ID have been shown to have more restricted social networks that they were less satisfied with than a reference group from the general population (van Asselt-Goverts et al. Citation2015). Stressful social interactions might occur more frequently in the lives of people with ID compared to the general population. Indeed, people with ID are more dependent on support in daily life (Catani and Sossalla Citation2015), and are more likely to be confronted with involuntary support and overprotection from other people in daily activities and decision making, who may not adequately consider their individual autonomy (Björnsdóttir et al. Citation2015). It can therefore be assumed that social support plays a different role in the lives of people with ID compared to the general population, and that the discrepancy between the provided social support and the subjectively perceived social support is likely to be even more pronounced in people with ID (Maercker and Horn Citation2013). Accordingly, it stands to reason that the protective role that social support has in the general population cannot simply be transferred to the population of people with ID. The distinction between different forms of negative social reactions (TA and UA) as proposed by Relyea and Ullman (Citation2015) might be helpful in understanding the role of social support in people with ID. While reactions of UA might have been intended as support by the disclosure recipient, survivors with ID might not perceive these reactions as supportive and benevolent. Given the special relevance of social support in the daily life of people with ID, distinguishing between reactions of TA and UA might be helpful in understanding the mediating role of social support in trauma survivors with ID.

The role of the distant social context for people with ID

Maercker and Horn (Citation2013) highlight the importance of the distant social context: culture and society in the aftermath of trauma. There are a number of risk factors for women with ID in the distant social context. Access to victim protection and support facilities is hampered by a series of barriers (Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights et al. Citation2014). Moreover, people often view the topic of sexuality as a taboo, especially in women with ID. Therefore, women with ID often do not receive adequate sexual education and might be unable to recognize sexual violence (Iudici et al. Citation2019, Catani and Sossalla Citation2015). Furthermore, they have greater difficulties in reporting crimes due to their verbal limitations and are thus at greater risk of not being believed. Additionally, women with ID are often considered as less credible due to stereotypes about the sexuality of women with ID (Iudici et al. Citation2019, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights et al. Citation2014). Finally, information is often not available in an easy-to-read form, and women with ID lack information on how to access the help system. Understanding of the processes, for instance to access the help system or justice, is often limited in women with ID, and professionals are often not well-equipped to cater to the needs of these women. Moreover, specialised services for women with ID are often not competent in dealing with interpersonal trauma (Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights et al. Citation2014).

Current study

The current study aims to explore the subjective perception of benevolence and harmfulness of social reactions received upon disclosure of sexual violence in women with ID. A qualitative case study approach was chosen, as it offers the possibility to gain a holistic view of the experiences of women with ID after the disclosure of sexual violence and understand them in their full complexity (Beail and Williams Citation2014, Kohlbacher Citation2006). The distinction of social reactions into the three categories according to Relyea and Ullman (Citation2015) was used to guide the qualitative analysis. Previous literature has already emphasised the importance of understanding how different kinds of social reactions affect survivors in order to improve the ability of professionals and community members to provide support to survivors who have disclosed sexual violence (Relyea and Ullman Citation2015).

Based on four qualitative interviews with women with ID who had experienced sexual violence, the following research questions were addressed:

Which reactions to the disclosure of sexual violence did women with ID perceive as benevolent?

Which reactions to the disclosure of sexual violence did women with ID perceive as harmful?

Did women with ID subjectively perceive any difference in the social reactions that they received due to their diagnosis of ID?

Method

Participants

The current sample (n = 4) was drawn from a larger sample of people with ID who participated in a previous study conducted by the current authors (Rittmannsberger et al. Citationunder review). The sample was referred to the authors as having mild to moderate ID by the institutions and caregivers caring for them. Caregivers estimated the current sample to be functioning within the mild –moderate range of ID. Inclusion criteria for the current study were female sex, exposure to sexual violence in their biography, sufficient verbal competence, and sufficient psychological stability to participate in this potentially stressful interview, as judged by their caregivers. An overview of demographic data and results from the previous study regarding trauma biography and PTSD symptoms in the four women is presented in .

Table 1. Sample description.

Procedure

The current data were collected in the course of a larger study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Vienna (reference number: 00283; date of approval: 02.11.2017). Participants were approached in a top-down process and through snowball sampling. The authors contacted specialised institutions for housing and employment in Austria to recruit people with ID in a top-down process. The study information included an easy-to-read leaflet for people with ID and another leaflet for caregivers. This information covered the aims, process and implications of the current study. If desired, the corresponding author presented the study in a personal meeting with caregivers and potential participants. Caregivers who work directly with people with ID selected potential participants. In some cases, participants were contacted directly, for example at a congress for self-advocates. A total of 49 people with mild to moderate ID participated in a questionnaire assessment. Of these, interested participants were assessed for the inclusion criteria for the qualitative study. All eligible women knew the interviewer from a previous assessment and agreed to participation. Interviews were conducted on-site by the corresponding author in either living or working facilities. Before the interviews, participants signed an easy-to-read informed consent form that explained how the data would be handled. The interviews took place in one session per participant and lasted between 12:06 and 25:54 min. If necessary, short psychological interventions were offered following the interview. Additionally, participants were provided with a list of specialized institutions (e.g. crisis lines or counseling centers) and a hotline run by the authors to call in the case of problems or further questions.

The interviewer is female, a trained clinical psychologist and currently a research associate at the Department of Applied Psychology at the University of Vienna. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded by two raters (the first and the third author).

Measures

Symptoms of PTSD were assessed using the Lancaster and Northgate Trauma Scales for ID Self-Report Version (LANTS) (Wigham et al. Citation2011). The LANTS-SR comprises 29 questions assessing possible effects of traumatic events on people with ID. These effects go beyond those defined for the general population and include specific effects of traumatic events in people with ID. The applied interview guide was semi-structured and included only open questions. The interview intended to encourage participants to report their experiences of disclosure of sexual violence and the concrete social reactions they received. Participants were asked whether they perceived these reactions as benevolent or harmful. This question was further assessed by asking participants about their emotional response to the received reactions. Furthermore, the participants were asked whether they subjectively perceive any difference in the social reactions that they received because of their ID diagnosis.

Data analysis

Qualitative research has proved valuable in understanding the experiences of people with ID (Beail and Williams Citation2014). The current study used an exploratory, qualitative approach to answer the research questions. Qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation2014) is a systematic, rule-bound procedure and is well suited to complement case studies as an analysis and interpretation method, and was therefore used to underpin the analysis of the case study (Kohlbacher Citation2006). A case study approach provides the possibility to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events and hence enables the understanding of complex social phenomena (Yin Citation2003). Atlas.ti 8 (Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH Citation2002-2019) was used to organize the data. The software-aided analysis was conducted according to the approach suggested by Kuckartz (Citation2010), by carrying out the stepwise reduction process using the software instead of the original table (Larcher Citation2010; Mayring Citation2014).

To answer the present research questions, we applied a summarizing approach in order to achieve a reduction of the material while preserving the essential content (Mayring Citation2014). The segmentation into content-analytical units was defined as follows: The written transcripts of the original interviews formed the recording unit for the analysis, and the entire text of the four interviews, in condensed form, was defined as the context unit. The coding unit was defined as single comprehensible meaning units that represent complete statements on the queried topics.

Coding was carried out using an inductive approach, thus directly arriving at summarizing categories which come from the material itself and not from theoretical considerations. Inductive coding was chosen due to its exploratory nature and in order to preserve the language of the material (Mayring Citation2014). Data analysis was conducted in a stepwise generalisation process: First, a reduction of the primary text consisted in a condensation of the text into comprehensible meaning units, thus shortening the text while still preserving the core meaning (Erlingsson and Brysiewicz Citation2017). In this regard, original formulations were adopted to maintain a connection to the original statements. Due to the population-specific impairment in verbal skills, short and one-word responses were extended by wording of the interviewer (e.g. questions affirmed with ‘yes’ were supplemented with the question that had been asked). Next, these comprehensible meaning units were paraphrased into a content-focused short form. In a further step, paraphrases were reduced to generalisations to reach the level of abstraction of specific social reactions or emotional responses that were as general as possible but nevertheless still referred to the individual case. Finally, coding was applied to the generalisations, in order to reach a higher abstraction level of more general social reactions and emotional responses that can be applied to other cases. Examples of this process are provided in . The corresponding author carried out this process. After coding two interviews, the third author applied the codes resulting from the process. Coding was discussed until consensus was reached and codes were then applied to the remaining material.

Table 2. Examples for paraphrasing, generalisation and coding.

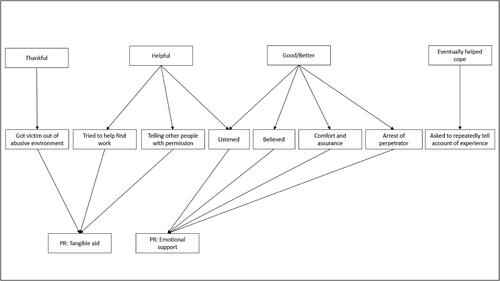

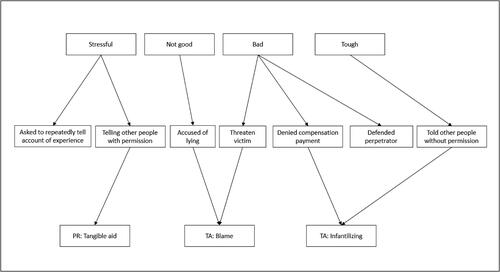

After applying this inductive approach to the generalisation, main category formation was carried out using a deductive approach, which takes into account the current state of research. The codes that resulted from the inductive coding process were grouped according to the categories of the SRQ (Ullman, Citation2000): Positive Reactions (PR), TA, and UA. PR include the subcategories emotional support and tangible aid, TA comprises the subcategories blame, stigmatizing, and infantilizing, and UA includes the subcategories taking control, distracting, and egocentric reactions. A more detailed description and examples for the SRQ categories are provided in . The assignment of codes was based on similarity of codes with items of the SRQ, and on the category description (Relyea and Ullman Citation2015) for codes that are not specifically included as items in one of the categories of the SRQ. Codes that did not fit the description of any category at all were categorised using an inductive approach. Social reactions were categorised into benevolent and harmful based on statements of whether these reactions were or were not helpful and considered the emotional responses to social reactions (stated). A graphical representation was created using the Atlas.ti network operation.

Table 3. Description and examples for SRQ categories.

Results

First, the four cases and the social reactions that the women received are described, including the assignment to SRQ categories. For the purpose of anonymisation, the women’s names have been changed. Second, the assignment of SRQ categories to the reported emotional responses is presented graphically.

Participant 1: Anna

Anna is a 52-year-old woman with ID. She experienced a single incident of sexual violence in her early teens. When disclosing this incident, people reacted with shock and could not believe that this had happened (UA: egocentric). She was eventually believed and received comfort and reassurance (PR: emotional support). She was taken to a psychiatrist (PR: tangible aid), who carried out a one-to-one conversation with her (PR: emotional support). She received help in trying to bring the perpetrator to account (PR: tangible aid). However, the perpetrator was not arrested (TA: infantilizing). Throughout this process, she was asked to repeatedly give her account of the incident, which she perceived as stressful, but which eventually helped her to cope. She reports one particular reaction that made her feel worse: when a carer told other people about the incident without her permission (TA: infantilizing). She states that this was tough for her. She was defended against this unfair reaction, which made her feel better (PR: emotional support). Anna does not think that people would have reacted differently if she had not had an ID diagnosis. On the contrary, she has received positive reactions. Everybody is surprised and proud of her for developing so well despite the ID diagnosis and the experience of sexual violence.

Participant 2: Barbara

Barbara is a 44-year-old woman with ID. She experienced sexual violence as a 12-year-old, perpetrated by her stepfather at home. The incident was first uncovered in a conversation with her teacher, who suspected that something was wrong (PR: tangible aid). This teacher believed Barbara and confronted her mother and stepfather (TA: tangible aid). Barbara found this situation to be stressful. The perpetrator denied the incident (TA: blame). Barbara’s mother defended the perpetrator and denied the incident (UA: egocentric), which Barbara described as ‘bad for her’. Her teacher got her out of the abusive environment (PR: tangible aid), which Barbara perceived as helpful and for which she felt thankful. The perpetrator was not held accountable (TA: infantilizing). Barbara feels that the diagnosis of ID did not have an impact on the social reactions she received. She thinks that anyone would have been treated that way.

Participant 3: Carol

Carol is a 52-year-old woman with ID who experienced a single traumatic event of sexual violence by a stranger. She disclosed the incident to her boss at work, who believed her, made it clear that the perpetrator was to blame for what happened (PR: emotional support) and took her to the police (PR: tangible aid). After a trial, where Carol felt comfort and reassurance from her social network, the perpetrator was imprisoned (PR: emotional support), which she describes as good for her. Carol does not think that anyone treated her differently because she has a diagnosis of ID.

Participant 4: Donna

Donna is a 49-year-old woman with ID. She experienced an incident of sexual violence at her workplace. She disclosed the incident at her workplace, where she was not believed and was accused of lying (TA: Blame). The perpetrator was confronted, but denied the incident and reframed the victim as a perpetrator. Donna was suspended from her workplace (TA: Blame). The institution told her not to attract attention in order to protect the institution (TA: infantilizing). She reported the incident to the police and was taken to a medical officer (PR: tangible aid), who did not believe her and refused to examine her (TA: infantilizing). She finally withdrew the police report. She disclosed the incident to one of her family members, who believed her, listened to her, and offered comfort and reassurance (PR: emotional support). With Donna’s permission, the family member told her mother about what had happened, which Donna perceived as helpful (PR: tangible aid). Her mother blamed and scolded her (TA: blame), which Donna perceived as stressful, but the mother also tried to prevent negative consequences (PR: tangible aid), which Donna perceived as helpful. However, her mother’s attempts remained unsuccessful and Donna did not receive any compensation payment or get her job back (TA: infantilizing), which she describes as bad for her. Donna feels that she was treated unfairly and discriminated against by her boss because of her ID.

Main categories

The assignment of the inductively retrieved social reactions to the SRQ categories indicates that the following SRQ categories occurred in our sample: PR: emotional support and tangible aid; UA: egocentric; TA: blame and infantilizing. The current participants did not report social reactions (that can be classified) as (TA) stigmatising, or (UA) taking control and (UA) distracting. Not being believed is the only social reaction received by the current participants (when disclosing sexual violence) that is not included in any of the SRQ categories.

The social reactions that current participants perceived as benevolent belong to the categories of PR: tangible aid, e.g. tried to help find work or and PR: emotional support, e.g. listened and comfort and reassurance (see ). The social reactions that current participants perceived as harmful belong to the categories of TA: blame, e.g. accused of lying, threaten victim; and TA: infantilizing, e.g. denied compensation payment, and defended perpetrator but also PR: tangible aid (see ). Participants did not report any emotional reactions from the category of UA.

Discussion

This study set out to assess the subjective perception of the benevolence or harmfulness of social reactions received by women with mild to moderate ID when disclosing incidents of sexual violence. It can be assumed that the perception of supportive social reactions differs in people with ID, due to their general dependency on sometimes unwanted social support in their daily lives. The women reported reactions of infantilizing and blame (TA), which they perceived as hurtful. Positive reactions were consistently described as benevolent. This is in line with findings from the general population (Campbell et al. Citation2001). Previous studies indicate that TA reactions were associated with higher PTSD symptoms (Peter-Hagene and Ullman Citation2014, Ullman and Peter-Hagene Citation2014). Positive reactions were associated with lower PTSD symptoms (Ullman and Peter-Hagene Citation2014). Both studies highlight the role of perceived control as an important mediator of this relationship. In people with ID, perceived control over recovery can be assumed to play an important role in the aftermath of sexual violence. Control and self-determination are intensively discussed topics in research concerning the population with ID (Frielink et al. Citation2018). People with ID have been reported to perceive a lack of control over their social life, sexuality and intimacy (Black and Kammes Citation2019). The role of perceived control might therefore be informative for the understanding of the role of social reactions for the processing of sexual violence in this population. This is an interesting topic for future studies.

Previous studies in the general population have shown that survivors perceived UA reactions ambivalently, both as benevolent and harmful (Relyea and Ullman Citation2015). Surprisingly, this could not be replicated in this study, since the current participants reported no social reactions that can be assigned to distracting (UA) or taking control (UA), and no statements regarding the perceived valence or emotional response to received egocentric reactions (UA).

In two cases there was an overlap between the perception of benevolence and harmfulness of one single reaction: Anna reported being asked to repeatedly tell the account of her traumatic experience, which she experienced as stressful. However, she also perceived it as helpful in coping with the event. Avoidance of thoughts and feelings that are related to the traumatic experience is a core symptom of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that being asked to talk about the experience is stressful. At the same time, the retrospective perception of the helpfulness can also be logically explained by the fact that repeated exposure to the memory of the experience enables processing of the event (Shapiro Citation2017). Exposure represents the core feature of evidence based therapy for PTSD, such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) (Cusack et al. Citation2016; National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) Citation2005). The feasibility of EMDR in people with mild to moderate ID has been shown in a pilot study (Karatzias et al. Citation2019).

Three out of the four participants felt that they were not treated any differently to how they would expect a person without a disability to be treated. However, their reports do reveal injustice in social reactions in dealing with the disclosed sexual violence: In all but one case, perpetrators were not held accountable and did not have to bear any consequences. In two cases, no hearing or trial was held. One woman reported that she had to withdraw her police report because she was not taken seriously or believed and was even accused of lying. These negative reactions are also common in the general population (Ullman and Peter-Hagene Citation2014). Moreover, the women interviewed in the current study might not be representative for women with ID, who have been exposed to sexual violence through a natural sample bias that this study entails. Furthermore, the efforts and effects of the self-advocacy movement arising in the past decades have certainly contributed to an increased empowerment of people with ID (Goodley and Ramcharan Citation2010).

However, it has been suggested that women with ID still face several barriers in the aftermath of exposure to sexual violence. It is possible that the current participants did not perceive unequal treatment due to a habituation and the internalisation of societal attitudes towards women with ID, such as negative stereotypes about women with ID, e.g. negative perceptions of their sexuality and capacity for autonomy (Iudici et al. Citation2019) and lower self-esteem in women with ID compared to women without a disability (Nosek et al. Citation2003). As such, women with ID might be less likely to assert their rights before courts (Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights et al. Citation2014), resulting in a high number of women with ID who do not report crimes that have been perpetrated against them (Iudici et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, it is also possible that overprotective or stigmatizing reactions have been internalised in these women.

Cultural and societal attitudes have an impact on coping with trauma exposure (Maercker and Horn Citation2013). An environment that is only moving slowly towards perceiving women with ID as autonomous and self-determined, also in their sexuality, discourages help-seeking behaviour and hence excludes women with ID from evidence-based treatment possibilities. A lack of societal acknowledgment of the traumatic event and the victim, the failure to call perpetrators to account, barriers to accessing justice, and structural shortcomings regarding adequate support, are all likely to aggravate the effects of the trauma and increase the risk of re-victimisation.

Research implications

The associations between social reactions and processing of events of sexual violence provide a fruitful area for research. However, to guide policy makers, programmes and empowerment interventions, a sounder evidence base is needed (Iudici et al. Citation2019). The present study should be repeated using a larger sample. A natural progression of this work would be to develop a specific questionnaire on social reactions to disclosure of trauma exposure for people with ID. In addition to the subjective perception of survivors, further research should explore the relationship between received social reactions and psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD. Furthermore, the role that perceived control and coping mechanisms play in this relationship should be addressed.

Clinical implications

Understanding the subjective perception of the benevolence and harmfulness of social reactions to disclosure of sexual violence can help caregivers and responders to provide the right kind of support for women with ID. It is important, especially following trauma exposure, to strengthen self-esteem in women with ID in order to help them to stand up for their rights, fight injustice, and demand consequences for perpetrators. Empowerment programmes and improved structural support that is sensitive to the needs of women with ID who have experienced sexual violence should be designed.

Limitations

The current study relies on retrospective accounts. The ability to provide accounts of events that in part took place long ago might be especially impaired due to the ID. The current study was prone to a sample bias resulting from the participant recruitment process. Participants were pre-selected by their caregivers, who considered them stable enough to tolerate this potentially stressful interview situation. Furthermore, the assessment of the degree of ID was unstandardized. A standardized assessment of intellectual functioning was beyond the scope of the current study. A natural progression of this work would therefore be a larger study, striving to recruiting people with ID directly and involving a standardized assessment of the degree of ID. Furthermore, as verbal ability is limited in people with ID, so too is the capacity to describe emotional responses. The use of visual aids might be helpful tools in assessment of such intrapsychic states of people with ID.

Study strength

This is the first study to assess social reactions to disclosure of sexual violence in women with ID. Qualitative research is becoming increasingly relevant in research in people with ID (Beail and Williams Citation2014). An exploratory approach to this topic assures that it is captured individually for people with ID and does not merely assume that concepts from the general population also apply to this group of people.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association 1980. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH 2002-2019. ATLAS.ti. Berlin: Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH.

- Beail, N. and Williams, K. 2014. Using qualitative methods in research with people who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 85–96.

- Björnsdóttir, K., Stefánsdóttir, G.V. and Stefánsdóttir, Á. 2015. It’s my life’: Autonomy and people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 5–21.

- Black, R.S. and Kammes, R.R. 2019. Restrictions, power, companionship, and intimacy: a metasynthesis of people with intellectual disability speaking about sex and relationships. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57, 212–233.

- Brewin, C.R. 2014. Episodic memory, perceptual memory, and their interaction: foundations for a theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 69–97.

- Brewin, C.R., Andrews, B. and Valentine, J.D. 2000. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 748–766.

- Byrne, G. 2018. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with an intellectual disability: a review of the recent literature. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 294–310.

- Campbell, R., Ahrens, C. E., Sefl, T., Wasco, S. M. and Barnes, H. E. 2001. Social reactions to rape victims. Healing and hurtful effects of psychological and physical health outcomes. Violence and Victims, 16, 287–302.

- Catani, C. and Sossalla, I. M. 2015. Child abuse predicts adult PTSD symptoms among individuals diagnosed with intellectual disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–11 .

- Cusack, K., Jonas, D. E., Forneris, C. A., Wines, C., Sonis, J., Middleton, J. C., Feltner, C., Brownley, K. A., Olmsted, K. R., Greenblatt, A., Weil, A. and Gaynes, B. N. 2016. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 128–141.

- Erlingsson, C. and Brysiewicz, P. 2017. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7, 93–99.

- Focht-New, G., Clements, P. T., Barol, B., Faulkner, M. J. and Service, K. P. 2008. Persons with developmental disabilities exposed to interpersonal violence and crime. Strategies and guidance for assessment. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 44, 3–13.

- Fogden, B. C., Thomas, S. D. M., Daffern, M. and Ogloff, J. R. P. 2016. Crime and victimisation in people with intellectual disability: A case linkage study. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 1–9.

- Frielink, N., Schuengel, C. and Embregts, P.J.C.M. 2018. Autonomy support in people with mild-to-borderline intellectual disability: testing the Health Care Climate Questionnaire-Intellectual Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 159–163.

- Goodley, D. and Ramcharan, P. 2010. Advocacy, campaigning and people with learning difficulties. In: G. Grant, ed. Learning disability. A life cycle approach. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill/Open University Press, 87–100.

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., McCoy, E., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T. and Officer, A. 2012. Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379, 1621–1629.

- Hulbert-Williams, L., Hastings, R. P., Crowe, R. and Pemberton, J. 2011. Self-reported life events, social support and psychological problems in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24, 427–436.

- Iudici, A., Antonello, A. and Turchi, G. 2019. Intimate partner violence against disabled persons. Clinical and health impact, intersections, issues and intervention strategies. Sexuality & Culture, 23, 684–704.

- Karatzias, T., Brown, M., Taggart, L., Truesdale, M., Sirisena, C., Walley, R., Mason‐Roberts, S., Bradley, A. and Paterson, D. 2019. A mixed-methods, randomized controlled feasibility trial of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) plus standard care (SC) versus SC alone for DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32, 806–818.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Levinson, D., Navarro-Mateu, F., Pennell, B.-E., Piazza, M., Posada-Villa, J., Scott, K. M., Stein, D. J., Ten Have, M., Torres, Y., Viana, M. C., Petukhova, M. V., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M. and Koenen, K. C. 2017. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8, 1353383.

- Kohlbacher, F. 2006. The use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 7, 1–30.

- Kuckartz, U. 2010. Einführung in die computergestützte Analyse qualitativer Daten. 3rd ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Larcher, M. 2010. Zusammenfassende Inhaltsanalyse nach Mayring. Überlegungen zu einer QDA-Software unterstützen Anwendung. Wien: Universität für Bodenkultur.

- Lueger-Schuster, B., Butollo, A., Moy, Y., Jagsch, R., Glück, T., Kantor, V., Knefel, M. and Weindl, D. 2015. Aspects of social support and disclosure in the context of institutional abuse - long-term impact on mental health. BMC Psychology, 3, 19.

- Lunsky, Y. and Benson, B.A. 2001. Association between perceived social support and strain, and positive and negative outcome for adults with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45, 106–114.

- Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights, Queraum. cultural- and social research, Mandl, S., Schachner, A., Sprenger, C. and Planitzer, J. 2014. Access to specialised victim support services for women with disabilities who have experienced violence. Final Report.

- Maercker, A., Hilpert, P. and Burri, A. 2016. Childhood trauma and resilience in old age: applying a context model of resilience to a sample of former indentured child laborers. Aging & Mental Health, 20, 616–626.

- Maercker, A. and Horn, A.B. 2013. A socio-interpersonal perspective on PTSD: the case for environments and interpersonal processes. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20, 465–481.

- Mayring, P. 2014. Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. Available at: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/39517

- Mevissen, L. and De Jongh, A. 2010. PTSD and its treatment in people with intellectual disabilities: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 308–316.

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2005. Post-traumatic stress disorder. The management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Leicester (UK): Gaskell.

- Nosek, M. A., Hughes, R. B., Swedlund, N., Taylor, H. B. and Swank, P. 2003. Self-esteem and women with disabilities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 56, 1737–1747.

- Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L. and Weiss, D. S. 2003. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 52–73.

- Peter-Hagene, L.C. and Ullman, S.E. 2014. Social reactions to sexual assault disclosure and problem drinking: Mediating effects of perceived control and PTSD. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1418–1437.

- Relyea, M. and Ullman, S. 2015. Unsupported or turned against. understanding how two types of negative social reactions to sexual assault relate to post-assault outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39, 37–52.

- Rimé, B. 2009. Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1, 60–85.

- Rittmannsberger, D., Weber, G. and Lueger-Schuster, B. under review. Applicability of the PTSD gate criterion in people with mild to moderate ID. Do additional adverse events impact current symptoms of PTSD in people with ID.

- Shapiro, F. 2017. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, third edition. Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. New York: Guilford Press.

- Ullman, S. E. 2000. Psychometric Characteristics of the Social Reactions Questionnaire: A Measure of Reactions to Sexual Assault Victims. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 257–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00208.x.

- Ullman, S.E. 2011. Is disclosure of sexual traumas helpful? Comparing experimental laboratory versus field study results. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20, 148–162.

- Ullman, S.E. and Peter-Hagene, L. 2014. Social reactions to sexual assault disclosure, coping, perceived control and ptsd symptoms in sexual assault victims. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 495–508.

- van Asselt-Goverts, A. E., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C., Wegman, K. M. and Teunisse, J. P. 2015. Do social networks differ? Comparison of the social networks of people with intellectual disabilities, people with autism spectrum disorders and other people living in the community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 1191–1203.

- Wigham, S. and Emerson, E. 2015. Trauma and life events in adults with intellectual disability. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 2, 93–99.

- Wigham, S., Hatton, C. and Taylor, J.L. 2011. The Lancaster and Northgate Trauma Scales (LANTS): The development and psychometric properties of a measure of trauma for people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2651–2659.

- Wigham, S., Taylor, J.L. and Hatton, C. 2014. A prospective study of the relationship between adverse life events and trauma in adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 1131–1140.

- Yehuda, R. and McFarlane, A.C. 1995. Conflict between current knowledge about posttraumatic stress disorder and its original conceptual basis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 1705–1713.

- Yin, R.K. 2003. Case study research. Design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.