ABSTRACT

Objective: This paper represents an understanding of the ‘usability’ and ‘user experience’ of the TreCLifeStyle mobile app from an end-user experience in order to consider dietary food habit (e.g. Mediterranean Diet).

Methods: A qualitative and quantitative approach was undertaken using the system usability scale questionnaire and semi-structured interviews in 2 phases that occurred over a period of 12 consecutive weeks. Six families (n = 12) of Trentino province, Italy, were included who have one obese child as primary inclusion criteria.

Results: Incorporating three different aspects, (1) user preference, (2) usability evaluation and (3) system usability scale result; the study explains diversified end-user experiences. The outcome of the study addresses inadequate concentration of user-centered requirements from design to implementation level of a healthcare app. The users’ prioritise the appB (score >68) in terms of friendly interface usability and elaborative contents. Additionally, they identify necessary technological modifications at some point to operate the app seamlessly.

Conclusions: The study concludes with a strong demand for end-users’ engagement to design user-friendly mHealth app interfaces where the socio-cultural needs should be considered significant.

Introduction

The recent proliferation of information technologies and digitalization processes is a profound innovative practice. This sector is still emerging. To make the health information platform stronger, a growing number of web portals, online health forums, and text messaging services are accommodating the exchange of health-related information [Citation1–3]. Digital innovation is an idea, practice or object that is perceived as new domain by an individual or some other unit of adoption [Citation4]. As estimated, the number of mobile phone users across the world is expected to pass the five billion marks by 2019 [Citation5] and right now, nearly 67 percent of the population worldwide is already owning a mobile phone [Citation6]. This remarkable revolution – widespread access to the most ubiquitous communication device in human history – has changed the way of societies and communities to organize themselves and do business [Citation7]. As a part of that process, currently, there are 3,195,204 active mobile application (apps) available in the iTunes app store and the 3,612,250 active apps in the Google Play store, 95,851 and 105,912, respectively, were categorized as Health and Fitness in healthcare service system with a great concern of usability evaluation of the interfaces [Citation8,Citation9]. People who live in a remote place and face challenges with transportation are generally unable to access adequate health facilities. To mitigate this deprivation, information and communications technology offers an important component in healthcare sector through innovative tools such as telemedicine, electronic health (eHealth), and mobile health (mHealth) [Citation10]. This research paper adopts mHealth as a subdivision of eHealth.

Presently, mHealth services are working as a means of entering patient data into national health information systems, and as remote information tools which provide information to the government, healthcare clinics, home providers, and health workers [Citation11]. For instance, in developing countries, the key applications for mHealth are remote data collection, remote monitoring, communication and training for health workers, disease and epidemic outbreak tracking, diagnostic and treatment support. However, it helps to identify the individual and community health needs from clinical domain with almost negligible importance on socio-cultural perspectives. Most of the recent mHealth services provide a range of facilities focusing particularly on technological features [Citation12–15] and process improvement in healthcare service delivery [Citation16]. A subset of mHealth service reviews focus on short message service or mobile texting yet find little rigorous evidence of effectiveness such as behavior change interventions [Citation12,Citation17,Citation18] and there are both substantial and limited effects on how mobile phone technology can help to improve healthcare service delivery [Citation19,Citation20]. Consequently, a significant number of projects to date have overlooked the juxtaposition between ‘technological services’ and ‘social practices’ which has been addressed in this study.

This paper discusses the usage and the impact of a particular mobile app, TreCLifeStyle, which provides the techno-healthcare services in the contemporary healthcare sector and Mediterranean diet (MD) in Northern towns in Italy. Mediterranean diet pyramid is based on food patterns typical of Crete, much of the rest of Greece, and southern Italy in the early 1960s and beyond [Citation21]. The adult life expectancy, in these areas, was among the highest in the world and the rates of coronary heart disease, certain cancers, and other diet-related chronic diseases were among the lowest in the world according to previous research [Citation22]. This special diet pyramid is still proclaimed the apex position in terms of food habit and soundly practiced in all over Italy. This study kept a focus on understanding user experiences and preferences concerning the TreCLifeStyle operator interface. The valuation provided a comprehensive image of demand and supply side that could be a feasible framework for stakeholders, app designers/developers, and policy-makers to reconsider mHealth service implementation from a user-centered perspective.

Methods

In order to develop a broader understanding of mHealth usage, the research adopted influential research tools and methods to identify the perspectives of grass-root level beneficiaries. Moreover, preexisting definitions of ‘mHealth’ have been considered to conceptualize usage, socio-cultural needs and its relation to the research. The study implemented a mixed method approach that places priority on the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data. Participants underwent a semi-structured interview including questions about interface preference, dietary behavior, and user experience (UX). In addition, a ‘SUS ideal format’ [Citation23] has been tested to collect the score for both appA and appB. Brook explained, if the score is under 68, there are probably serious problems with the interface usability which should be addressed [Citation23]. On the other hand, while the score is 80.3 or above that indicates people love the interface without hesitation and will recommend to their friends. To understand the dietary changes (whether it happened or not), this study adopted ‘Stage of change or Transtheoretical model’ [Citation24,Citation25] and the ‘Heuristic model’ [Citation26] to accomplish the desired UX objective.

Participants

This study selected three rural areas of Trentino province, Italy – GRUMO, GARDOLO, and RIVA del GARDA – as the field site and took two families from each place as study participants. All the families were selected through a purposive sampling of families who had an obese child contacted through enlisted pediatricians of a local organization, named Fondazione Bruno Kessler (FBK). Twelve participants (), mother or father and the child with the obesity issue asked to use the app, were interviewed for the study (n = 12); eight were female (five mother, three girl); four were male (one father, three boy). We informed the participants and fixed a time schedule, prior to formal interview has facilitated by the researcher with the help of FBK correspondents, based on participant’s availability.

Table 1. Participant details.

Data Collection

Data collection follows questionnaire survey, system usability scale (SUS) and semi-structured interviews in 2 phases that lasted for 12 consecutive weeks and occurred between April and June 2016. Each interview, took place in participant’s closer vicinity, was recorded and lasted about 20–30 min. Most of the interviews and SUS questionnaires were completed in Italian language and later subjected to a translation by a research assistant.

Ethical consideration

The Research Ethic Committee of University of Trento, Italy, has approved to conduct the study. All respondents (both parents and children) confirmed their voluntary verbal informed consent to participate in the research and voice recording. Three ethical principles [Citation27] were taken into account to avoid possible risk factors. Firstly, respondents were informed that they had the right to withdraw at any time during the interview and were assured anonymity would be provided across all stages of the study to ensure the ‘respect for persons’; secondly, participants were also provided with information regarding ‘beneficence’ (to do no harm, minimize risk of harm and maximize the benefits of research); finally, the study selected the participants equitably and avoided exploitation of vulnerable populations to justice was maintained.

Data analysis

The study adopted ‘mixed analysis’ for data analysis which is guided by either a priori, a posteriori, or iteratively [Citation28]. It simultaneously refers to a process of ‘mixing’ and/or ‘combining’ qualitative and quantitative data into a single study to provide richer data interpretations [Citation29]. Verbatim quotations [Citation30,Citation31] from study participants were used throughout the paper. The study presents analytical curves both for qualitative and quantitative data according to requirement. Qualitative data are followed narrative description whereas quantitative data exemplified through graphical presentation along with a precise explanation. The first author was responsible for conducting and analyzing all interview data.

Results

cThe TreCLifeStyle app had launched two versions (appA and appB) during the study period. After using both versions of the app for a certain time, the study result showed end-users’ preference in terms of user-friendly interfaces. User preference comprised with excerpts of children and parents. Usability evaluation was measured based on a structured questionnaire emphasizes on the influence of the TreCLifeStyle mobile app from individual to family level. End-users’ of this study preferred version B compared to version A, due to elaborative and user-friendly interfaces. The interface developers exclusively consider technological aspects, however, this study argued to put importance on incorporating user experience (UX) in interface designing process from the beginning. Therefore, in light of our findings, we addressed three interconnected aspects, namely user preference, usability evaluation, and system usability scale (SUS) that discussed below.

User preference

After completing both phases of the trial version of appA and appB, end-users got six more weeks to use any version according to their choice. The assessment process was based on two items- first-hand user experience and personal opinion about the interface – where the majority user preferred appB rather than appA ().

The mother of the first respondent (TL001) said – to understand the statistics about nutrients balance and calories – appB is convenient. She stated,

It is too easy to add a meal, due to the opportunity to indicate foods as dressings and to change the grams of food consumed. So that I consider the second version simpler and more intuitive and it is faster to add meals as well. (Mother of TL001)

The child who was using the Jawbone bracelet becomes curious to see the footsteps in his mobile phone. He said, ‘for me, the appB is better, it has the feature to choose or add the seasonings directly, we can change the grams according to our needs. This app also shows me the daily steps which make me interested’ (TL002).

The third respondent (TL003) shared her experience to give an opinion regarding app preference,

The second version (appB) is more comfortable to use because it is more direct. However, I also face some difficulties with appB as well. My father asked about pasta and ‘fagioli’ (beans), but there is an option for legumes, not ‘fagioli’. So, I suggest adding elaborated food items the Italian people used to eat (insalata russa, tortel di patate) in the interface. (TL003)

According to the mother of TL004,

I thank to appB because of the functionalities such as portions, statistics, and suggestions. I was more able to adapt my diet to this one. In particular, I found very interesting to visualize the calories consumed with the meals and then compare them with the burned calories shown on the misfit app. (Mother of TL004)

The mother of the fourth respondent (TL004) gave more noteworthy information to make her opinion clear and vibrant,

With the second app (appB) I was able to aware more about our diet, portions, and proportions among foods. This feature makes me motivated more to use the second version. Even though both the app is considerably easy to use and need no tutorial. I didn’t find incoherence between icon and functionalities and I received always a feedback to my interaction with the app. (Mother of TL004)

Sometimes the end-users faced challenges with the bracelet to synchronize real-time data, and the child used to lose it due to inconsistent physical activities. These challenges need for further attention.

For TL005, basically, the mother was using the app because the child is still learning how to use the app properly. She expressed her opinion indicating some interesting information regarding the preference of the interface. She said,

By the second app (appB) I have more control of eating habits and are more aware of health condition, thanks to the statistics on nutrients … . But I think that the first version (appA) contains more necessary information to know the Mediterranean diet. (Mother of TL005)

The mother of the sixth respondent (TL006) was happy to see the calories of the everyday meal and the portion she is using in her child’s meal. She pointed that with appB it is relatively easier to know how much calorie the child is consuming in every meal and how much is missing. This family uses the app quite frequently and the mother kept following the record on a regular basis. According to her,

… I prefer the Second version (appB), because it is very precise and gives particular information about calories … the other version (appA) did not give such information. In addition, the appA does not know whether to add a food such as a small piece of chocolate or half a slice of ham, and it does not indicate the food quantity. In appA, there was also a calorie problem … but now the second version (appB) is better … we receive more information on real energy intake so that we can also compare the consumed calories with burned calories through the pedometer of the appB. (Mother of TL006)

Usability evaluation

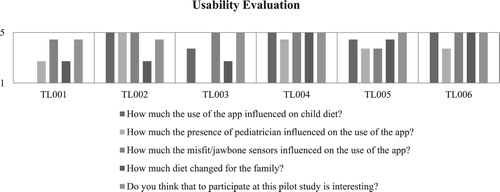

Usability does not exist in any absolute form; it can only be described in respect to a particular context. The study developed a usability assessment poll comprising of specific questions underlined on the influence of the TreCLifeStyle mobile app in respondents’ everyday life. The evaluation is scored from 1 to 5 scale; where 1 demonstrates the lowest influence and 5 implies the highest influence. In the field data, TL004 and TL006 were most influenced in every circumstance than others. However, TL001 confronted more issues in operating the app and the mother was using the app instead. ().

Concerning the influence of dietary inquiries, TL002, TL004, and TL006 demonstrated consistency and the rest of them have tended to a few difficulties. Particularly, the family food habit has been changed in each situation and every member feels the enthusiasm to partake in using the TreCLifeStyle app. This is a constructive indication that individuals are grasping present-day innovation and getting comfortable with utilizing it. As a result, respondents in every circumstance ended up with being independent and engagement of pediatricians are getting to be fewer. Children apply the jawbone bracelet every now and again to check their steps routinely. It becomes a pulling in and intriguing instrument to them.

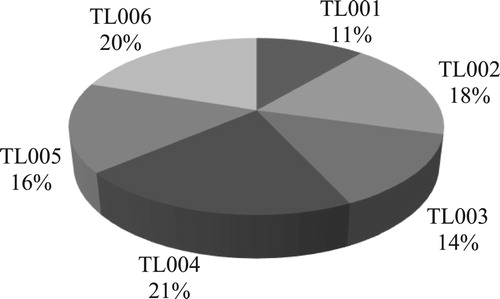

In aftermath, we see the changing pattern and the impact of the app among each family in percentage, with an exception of TL001 and TL003. Most of the families have scored over 15% while giving their opinions on the usability of the app. This measurement assigns a positive result of the app ().

System usability scale (SUS) result

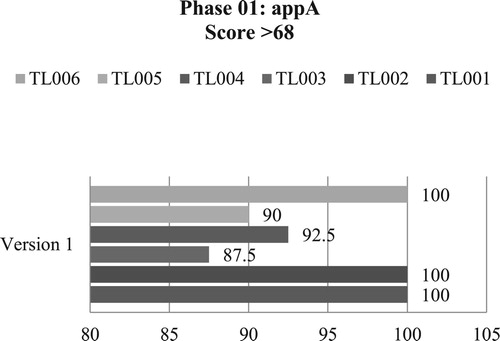

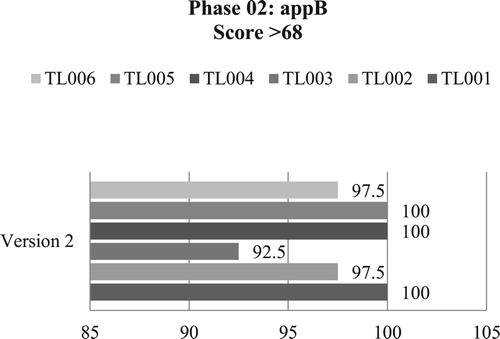

SUS is familiar as a form of Likert scale and proved as a dependable evaluation tool being robust and reliable [Citation23]. Every score of SUS represents a composite measure of the overall usability of the system studied [Citation32,Citation33]. To figure the SUS, scores for each question are converted to a new number. Each question’s score was kept running from 0 to 4. The aggregated scores need to multiply by 2.5 to acquire the general estimation of SUS [Citation23]. Despite the fact that the scores have a place 0–100, these are not percentages and ought to be considered as just regarding their percentile positioning. For the most part, SUS score >68 would be considered above average [Citation34]. If the score is <68, at that point, there are some significant problems with the interface usability, which should be addressed promptly. Regardless, if the score is over 68 that suggest the interface is likely on a right track.

To quantify the system usability, this study developed a questionnaire following the ‘ideal’ format of digital equipment corporation [Citation35] comprises of 10 questions. It was tested in two phases for version A and version B independently. However, the greater part of the questionnaire was related to the usability of the interface, some essential questions especially demonstrate the experiences and opinions of end-users. The scale set up one to five score to gauge the data where 1 signifies ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 implies ‘strongly agree’.

Both the diagram (Figures and ) represents the actual picture of the user experience. It appears to be each app is potentially usable and gained user satisfaction. During the first phase the users were using appA and the average score was above 85 whereas the average score is above 92 for appB in the second phase, which has obviously showed the entire fulfillment of the interface.

Nonetheless, the cross-analysis of the graphs exhibits that the usability extended progressively in the second phase. For instance, 5 points increased for TL003, TL004, TL005 and the score diminished for TL002 and TL006 of 3 points where the score proceeds as before for TL001. To clarify the reason, TL002 expressed, the interface of appA was much more simple to use even though the second version (appB) contains a lot more information. appB create difficulties to understand and operate the interfaces to some extent on account of huge amounts of data. The mother and the child were still learning the best way to use appB. On the other hand, the user TL006 mentioned that the appB is considerably more user-friendly and informative; yet it will take a bit more time to learn properly. She included, in contrast with both app, the second version is substantially more user-friendly to understand even though it might take longer time due to its sophisticated features.

Discussion

This section of the paper is followed by a summary discussion of the implications of the mHealth in terms of end-user experience and preference to develop a user-friendly interface for the healthcare system. The study findings conceptualized patient empowerment as an inherent component in health promotion. Patient empowerment refers not only the individual’s ability but also the controlling power over an object [Citation36]. It has been shown previously that patient empowerment is effective in self-management and contribute to the voluntary health behavior change [Citation7]. We also concluded a similar finding from our analysis.

With an obvious user variation from country to country, mobile phone penetration is forecasted to increase over the next few years due to the attractive features of smartphones. Thus, the usability testing gets gradual attention in interface design and does matter for mobile apps because it directly reflects the end-user’s satisfaction level with respect to application interfaces. Many people correlate the ‘usability’ concept solely with ‘ease of use’ of a product [Citation37]. However, the usability testing, by far, is regarded as an essential part to comprehend the effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use in the field of Health Information Technology [Citation38]. The study data showed that, on the understanding of usability concept and user experience (UX), the usability of a product is an imperative part that shapes its UX and both are dependable on each other. For example, version A of the TreCLifestyle app had fewer objects in comparison to version B, and users get less opportunity to accumulate all records they need to upload into the database. Consequently, the UX concluded appA with inadequate satisfaction and preference and went for version B in most cases. While the end-users were sharing their experiences, they consciously choose appB not only because of modified and user-friendly interfaces but also for the fulfillment of the requirements they have missed in appA.

Methods of usability evaluation for a mobile application and a website is similar to some extent, however, research exposed the standard usability testing practices are becoming complicated due to the variety of smartphones and Internet-capable feature phones [Citation39]. Thus, this study adopts the standard usability testing strategy. The usability assessment tool, under the name of ‘safety enhanced design’, of the study demonstrates a progressive impact of the TreCLifestyle mobile app on end-user’s daily food habit and physical activities. In addition, the usability evaluation result has given the context of the current usability status of appA and appB which produces an idea for designers who are looking for developing products with longevity.

Regarding the SUS score, it is important to remember that even though the score ranged from 0 to 100, it does not determine the percentage. For example, SUS score 68 out of 100 for this study represents the score is at the 68th percentile rather 68%. SUS score measures – especially those who are unfamiliar with SUS – usability, learnability, reliability, and validity of the interfaces of a mobile app and/or website. The score does not intend to diagnose and will not tell about specific problems of the interface, yet it gives red (negative) or green (positive) signal to know how badly the usability needs to work.

Considering Europe 2020 vision, the European Health Policy Forum and European Commission have already deployed a strategy of mHealth to ensure sustainable health services, however, the success depends on the crucial role of each member states [Citation10]. Some pilot mHealth projects have been scaled up to a broader level (national) with inadequate evidence on high-quality evaluation, [Citation40] while the usability evaluation of this study presents a viable empirical data. At the same time, reviews showed that mHealth app interventions to establish health indicators are very limited because of low participant engagement [Citation41]. Another empirical study revealed that the engagement contributes to patient empowerment to be able to make healthy decision and control of their behaviors [Citation7]. However, some studies also showed significant correlations in delivering health information [Citation42] and the outcomes of cost-effectiveness which are promising [Citation43]. Both from the commercial and service perspectives, mobile information and communication have the potential to revolutionize healthcare, particularly in low-resource settings of the low and the middle-income countries where healthcare infrastructure yet to be developed properly [Citation44]. As a result, the growing evidence on communication technologies and mobility of information in healthcare has attracted the attention of practitioners, academic researchers and policymakers globally [Citation45–47].

Scientific implication

Healthcare technologies create an opportunity for afflicting people around the world to continuously monitor health conditions, however, the research capacity requires development of a science of mHealth [Citation48]. The majority of mHealth apps based on nutrition and dietary habit are nascent and offering to deliver behavior change (BC) interventions in an effective way. These apps have limited implementation in disease management in primary health care services due to noticeable lack in respect to engaging adaptable theoretical framework. Moreover, the user-centered design (UCD) perspective in pediatric weight management has rarely been harmonized.

It is highly recommended to consider the UX importance in developing a user-friendly interface. We found similar argument in a recent study that reveals technological innovation cannot be isolated from cultural context and the management methods should be improved continuously with the support of end-user and service providers [Citation48]. The assessment result of UX and usability evaluation of the TreCLifeStyle app is such an intervention that entails an effective human and virtual coaching relationship to the families with overweight children. A significant finding of the study demonstrated the interactive interface (e.g. regular physical activities) which is more effective than exclusively providing training and health-related information. To our knowledge, this paper is one of the pioneer studies that accumulates BC and UCD to raise parents’ awareness about children’s eating behavior and lifestyle. Therefore, the TreCLifeStyle app will be an example of effective communication tool between health professional and patients.

Study limitations

From an empiric aspect, this paper is limited to specific healthcare-based mobile app. Any future research following similar strategies needs to be managed properly. Since the mobile app was implemented pilot basis, sometimes poor performance of the interfaces required us to spend more time unexpectedly. The participants were selected by the organization with the help of pediatricians who seemed reluctant to say something that might be considered too obvious. Moreover, the researchers have a language barrier to accurate analysis even though all the documents have been translated into English.

Conclusion

This article underlines the importance of end-user experience and preference to address the growing need for interdisciplinary scientific research approach in mHealth service. Since the unprecedented progress in technology often outpacing the research, effectiveness and sustainability can be ensured through establishing a network between health authorities and stakeholders [Citation48]. Findings imply that mHealth apps need for rigorous evaluation approach, advanced research methods, and should be tailored individually to achieve its potential.

Even though the TreCLifeStyle app interfaces require a minimal change, it can be considered an exceptionally valuable example to keep up the eating routine consistency. Then again, the app’s pop-up notification helps respondents’ to start following the instructions and the feedback to arrange their daily meal. For example, the child ends up simply enamored with the jawbone bracelet by observing the everyday footsteps. Now they come to know which food and what measure of nourishment they need to incorporate into every meal. This article’s results support the claim that integrating end-users in interface development and the extension of mHealth could contribute to improving health outcomes [Citation10]. Similarly, the user-centered design approach leads to the patient empowerment which found inevitable in order to have control over the determinants of individual’s quality of life [Citation7]. In spite of the fact that the mHealth apps are significantly diverse in nature and service quality, there are many commonalities that could be replicated directly from one to another. The findings from this study can also be supportive to the European nation states to be more caring in the development of mHealth interface. Therefore, the study concludes that ensuring end-users’ engagement in the health promotion interventions can play a crucial role in order to make it scalable, effective and impactful in the community.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all the participants in this study. The authors also thank FBK eHealth unit, Trento, Italy, Rosa Maimone, Silvia Fornasini and Marco Dianti for their support with the study’s implementation and data acquisition. The corresponding author is especially thankful to Prof. Kim Usher, University of New England for her valuable comments and A/Prof. Renato Troncon, University of Trento for his advice and feedback during the research work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Atiqur Rahman is currently pursuing his doctoral degree at Linköping University, Sweden. He has earned his previous master’s degrees in Anthropology from Bangladesh, and in Smart Community Design and Management (SCoDeM) from Italy. He is a public heath researcher with a strong background in qualitative research.

Yasmin Jahan is doing her PhD research at Hiroshima University, Japan. Before starting her doctoral research, she has completed her medical degree (MBBS) and Master of Public Health (MPH) degree from two reputed universities in Bangladesh. She has expertise in eHealth-based intervention research along with rigorous knowledge in clinical research.

Habibullah Fahad is working as a senior researcher at icddr,b. He completed his master and bachelor (hons) degrees in Anthropology. His longlasting experience and understanding in qualitative research are remarkable.

References

- Finney Rutten LJ, Davis T, Beckjord EB, et al. Picking up the pace: changes in method and frame for the health information national trends survey (2011–2014). J Health Commun. 2012;17(8):979–989.

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, et al. Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: associations with 10-year changes in body mass index. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(1):80–86.

- Oh B, Cho B, Han MK, et al. The effectiveness of mobile phone-based care for weight control in metabolic syndrome patients: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e83.

- Wejnert B. Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: A conceptual framework. Annu Rev Sociol. 2002;28(1):297–326.

- Statista. Number of mobile phone users worldwide 2013-2019 2017a [Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/274774/forecast-of-mobile-phone-users-worldwide/.

- Statista. M. Mobile phone penetration worldwide 2013-2019 2017 [Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/470018/mobile-phone-user-penetration-worldwide/.

- Ben Ayed M, El Aoud N. The patient empowerment: A promising concept in healthcare marketing. Int J Healthc Manag. 2017;10(1):42–48.

- AppBrain. Android statistics. 2018. [Available from: https://www.appbrain.com/stats/android-market-app-categories.

- Pocketgamer.biz. App store metrics. 2018. [Available from: http://www.pocketgamer.biz/metrics/app-store/.

- Miller LM. E-health: knowledge generation, value intangibles, and intellectual capital. Int J Healthc Manag. 2015;8(2):100–111.

- Suzanne Suggs L, Rangelov N, Schmeil A, et al. e-Health Services. The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society. 2015.

- Fjeldsoe BS, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2):165–173.

- Gurman TA, Rubin SE, Roess AA. Effectiveness of mHealth behavior change communication interventions in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Health Commun. 2012;17(sup1):82–104.

- Klasnja P, Pratt W. Healthcare in the pocket: mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45(1):184–198.

- Patrick K, Griswold WG, Raab F, et al. Health and the mobile phone. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):177.

- Blynn E. Piloting mHealth: A research scan. Cambridge (MA): Knowledge Exchange Management Sciences for Health; 2009.

- Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):56–69.

- Lim MS, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, et al. SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(5):287–290.

- Guy R, Hocking J, Wand H, et al. How effective are short message service reminders at increasing clinic attendance? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(2):614–632.

- Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2009;15(3):231–240.

- Vitiello V, Germani A, Capuzzo DE, et al. The New Modern Mediterranean diet Italian pyramid. Annali di Igiene: Medicina Preventiva e di Comunita. 2016;28(3):179–186.

- Dernini S, Berry EM. Mediterranean diet: from a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Front Nutr. 2015;2:15.

- Brooke J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale.. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, McClelland IL, et al., editors. Usability evaluation in industry. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd; 1996. p. 189–194.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- Norcross JC, Krebs PM, Prochaska JO. Stages of change. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):143–154.

- Nielsen J. Usability inspection methods. Conference companion on Human factors in computing systems; 1994: ACM.

- Beauchamp TL. The Belmont Report. The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics. 2008:21–28.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Combs JP. Data analysis in mixed research: A primer. Int J Educ. 2011;3(1):13.

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(2):112–133.

- Corden A, Sainsbury R. The impact of verbatim quotations on research users: qualitative exploration. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York (ESRC 2109); 2005. p. 1–55.

- Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, et al. Quality in qualitative evaluation: a framework for assessing research evidence. 2003.

- Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Human–Comput Interact. 2008;24(6):574–594.

- Bevan N. Usability is quality of use. Adv Hum Factors/Ergon. 1995;20:349–354.

- Kirakowski J, Corbett M. Measuring user satisfaction. Proceedings of the Fourth Conference of the British Computer Society on People and computers IV; 1988: Cambridge University Press.

- Chiu D-M, Jain R. Analysis of the increase and decrease algorithms for congestion avoidance in computer networks. Comput Netw ISDN Syst. 1989;17(1):1–14.

- Gibson CH. A concept analysis of empowerment. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16(3):354–361.

- Lowry SZ, Quinn MT, Ramaiah M, et al. A human factors guide to enhance her usability of critical user interactions when supporting pediatric patient care (nistir 7865). Electronic Health Records: Challenges in Design and Implementation. 2013;79.

- ISO S. 9241-11. (1998). Ergonomic Requirements for Office Work with Visual Display Terminals (VDTs)–Part II Guidance on Usability. 1998.

- Zhang J, Walji MF. TURF: toward a unified framework of EHR usability. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(6):1056–1067.

- Jordan E, Ray E, Johnson P, et al. Early results: text4baby program reaches the intended audience. Nurs Womens Health. 2011;15(3):206–212.

- Kohl LF, Crutzen R, de Vries NK. Online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviors: a systematic review of reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e146.

- Nundy S, Dick JJ, Chou C-H, et al. Mobile phone diabetes project led to improved glycemic control and net savings for Chicago plan participants. Health Aff. 2014;33(2):265–272.

- Harris J, Felix L, Miners A, et al. Adaptive e-learning to improve dietary behaviour: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2011;15(37):1–155.

- Kahn JG, Yang JS, Kahn JS. ‘Mobile’ health needs and opportunities in developing countries. Health Aff. 2010;29(2):252–258.

- Free C, Phillips G, Watson L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001363.

- Leslie I, Sherrington S, Dicks D, et al. Mobile communications for medical care: a study of current and future healthcare and health promotion applications, and their use in China and elsewhere. Cambridge: University of Cambridge; 2011.

- Waegemann CP. Mhealth: the next generation of telemedicine. Telemed JE Health. 2010;16(1):23–25.

- Bellandi G, Giannini M, Grande C. Mobile eHealth technology and healthcare quality impacts in Italy. Int J Healthc Manag. 2013;6(3):192–200.