ABSTRACT

Despite notable advancements, person-centered implementation is still propelled at a service level. This study aims to empirically determine organizational actions to achieve a person-centered culture through conceptual mapping of essential strategies. A participatory, multi-staged, group concept-mapping approach was employed. Mid and high-level healthcare managers responsible for managing healthcare delivery within the Malaysian Ministry of Health were recruited. In two separate meetings, 12 managers provided a set of related concepts and strategies, while 17 rated the importance and feasibility of implementation strategies. Cluster labels generated from the multidimensional scaling and hierarchical clsuter analysis were: multidisciplinary team, training and education, service user empowerment and quality assurance. The rating of statements created go-zone maps to determine the relative importance and feasibility of each person-centered strategy. Extending professional activities that cover a comprehensive spectrum of services and training healthcare providers on person-centered competency were rated the most important and feasible strategies. Nevertheless, these strategies must be balanced with additional resources to avoid the increasing workload to healthcare providers juggling many different tasks. In conclusion, the participatory evaluation allowed a better understanding of stakeholder-perceived priorities in developing short and long-term strategic plans for person-centered transformational practice and culture development.

Introduction

Healthcare institutions worldwide are beginning or have adopted the philosophy of person-centered care to improve safety and quality of care. Person-centered care involves engaging people using health and social services as equal partners in planning, developing, and monitoring care to meet their needs. The World Health Organization has also advocated that healthcare systems adopt a person-centered approach; the goal is to humanize healthcare by ensuring that it is rooted in universal principles of human rights and dignity, non-discrimination, participation and empowerment, access and equity, and partnership of equals [Citation1].

While there is no universally agreed-upon definition of person-centered practice, different medical and health care literature have used other terms to describe what matters to service users and how to provide care to ensure people have a good experience. These include person-centered medicine, person-centered care, patient-centeredness, individualized medicine, personalized medicine, family-centered medicine, patient-centric medicine, and patient-centric care [Citation2–4]. This lack of uniformity in defining person-centered practice resulted in many frameworks and guidelines, albeit with similar fundamental components [Citation5–7]. For this study, the Person-Centered Practice Framework was chosen due to its evidence-based approach and adaptability that ensures its applicability in various healthcare settings, and reflects the needs and preferences of all stakeholders involved in healthcare [Citation6].

Despite notable advancements in person-centeredness, health and social care cultures still need to evolve further to genuinely place people at the center of their care to achieve effective and meaningful outcomes. By recognizing the uniqueness of each person and their circumstances, and emphasizing the importance of building strong relationships between the user and the service provider, person-centered systems contribute to a variety of benefits, including improved access to care, improved health, and clinical outcomes, increased health literacy, higher rates of user satisfaction, improved job satisfaction among the health workforce, and more efficient and cost-effective services [Citation8, Citation9]. Nevertheless, adopting this philosophy depends on how well this concept is integrated and implemented at the system and organizational levels. Furthermore, the evolution of the concept has proceeded in a somewhat fragmented way, with limited coordination across sectors or specialties [Citation10]. The most significant challenge lies in transforming the theoretical guiding components into daily organizational practice that eventually forms the culture. This necessitates a sustained dedication to advancing practice, improving services, and implementing approaches that embrace continuous feedback, reflection, and engagement methods that allow for the inclusion of all voices.

Alongside advances in the research and scholarly literature, there has been a proliferation of policy- and strategy-focused publications supporting the need to develop person-centered cultures in healthcare. However, most current literature focuses mainly on ‘care’, with limited studies on how organizations can create person-centered cultures. From the point of view of the service users, the organizational actions required for person-centered practice include involving users in decision-making, developing individualized care plans, promoting communication and transparency, fostering a culture of respect and dignity, continuously improving services, and empowering staff [Citation11]. The work from West (2017) on compassionate leadership promulgated the idea of optimizing individuals to strengthen the organization, leading to an increased understanding of how service users’ experience and responses can be implemented into organizations [Citation2, Citation12]. At a macro level, healthcare providers are critical resources in high-quality care delivery. Unfortunately, their full range of skills are often underutilized and not well-recognized [Citation13, Citation14]. Therefore, person-centered managerial styles are needed [Citation15]. This includes collaborative and compassionate leadership that is inclusive and empowering, with clear planning and direction for the future to maintain a healthcare system that caters to the needs of service users and healthcare providers alike [Citation12]. Healthcare providers are empowered to establish relationships with the individuals receiving care by being given a voice and encouraged to do so. Besides adhering to the underlying principles, resources and funding must be available, and healthcare providers be trained and well-equipped with the skills for person-centered culture to materialize [Citation16, Citation17].

In Malaysia, the focus of healthcare shifted from disease-centered to person-centered since the enrollment of the 9th Malaysian Plan in 2006 [Citation18], with the expansion of services to involve more outreach programs, community involvement in care, and ensuring care is smooth through empanelment program whereby the same health team sees the service users for every outpatient visit [Citation19]. These activities propelled person-centered implementation at a service level. However, the implementation faces several challenges. First, healthcare providers need to be fully aware of the importance and benefits of person-centered care, as the cultural emphasis was more on the traditional biomedical model of care [Citation20–22]. Additionally, healthcare organizations need more resources, such as an integrated electronic health record shared across facilities, multidisciplinary teams, and service users [Citation23]. Due to time constraints and a lack of awareness, individuals’ involvement in healthcare decision-making may also hinder the adoption of person-centered care [Citation24–26]. Greater efforts are needed to empower service users to take charge of their health and be more actively involved in their care planning and decision-making, meeting their needs holistically. With these known issues, there is a need to explore how organizations may formulate new strategies to improve their current person-centered practice, ultimately forming a sustainable person-centered culture by gathering perspectives and opinions of stakeholders with rich experience on the current implementation and the barriers and challenges for change. The involvement of stakeholders in determining person-centered development and outcomes has been utilized in many studies [Citation27, Citation28]. To meet this complex need, our study aims to empirically determine the organizational actions required for person-centered culture to be achieved through conceptual mapping of essential strategies. Concept mapping methodology has been successfully applied in studying complex healthcare issues aimed at conceptualization, needs assessment, evaluation and program design [Citation29, Citation30]. Stakeholders can utilize the findings to prioritize and formulate person-centered action plans.

Methods

This study used participatory concept mapping to evaluate and integrate multiple individual perspectives [Citation31]. This methodology can drive changes within healthcare systems through its capacity to negotiate complexity and impact the structural and procedural outcomes of transformation [Citation32].

Study design and sampling

In this cross-sectional study, we employed a participatory, multi-staged, group concept-mapping approach integrating inputs from multiple sources with differing perspectives into a conceptual framework. It enabled the construction of visual maps representing the composite thinking of participants [Citation33]. Concept mapping also enables for a broad, holistic perspective that helps extend current understandings, generate new representations of the complexity in a person-centered organization, and facilitate collective action. This method has been widely used for applied social research to address healthcare issues [Citation34]. Group concept mapping was chosen since it garnered views from a broad group of people and was uniquely suited to community-engaged research [Citation31, Citation33]. In addition, it was effective for stakeholders’ engagement in clinical improvement activities [Citation35].

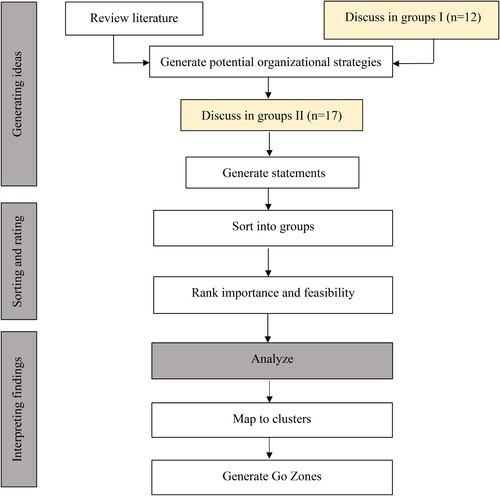

A purposive sampling strategy ensured we sampled the full spectrum of ideas. We recruited participants from various levels within the Ministry of Health organization, incorporating mid and high-level managers responsible for managing healthcare delivery at their respective organizations. Potential participants were identified among managers working in various primary care organizations across different states in Malaysia. They were chosen based on their relevance to the subject of the inquiry and their knowledge and experience in the field. This study was conducted from August to October 2018. The steps involved are detailed in the flow chart (), based on the methodology for concept mapping [Citation33].

Generating potential strategies

Key stakeholders were divided into multiple smaller groups of a maximum of five people. A brainstorming session was conducted to generate a list of ideas on possible organizational actions that could support person-centered culture. At the start of the session, participants were briefed on generating ideas relating to the study's focus statement on organizational strategies in implementing person-centered practice suited for the Malaysian public healthcare systems. Concepts were derived from literature review. These concepts were shared with participants who were asked to rate their agreement on implementing these strategies. This was followed by group discussion, where participants reviewed the strategies, taking their experiences into consideration, and provided additional thoughts for a given implementation strategy (e.g. specificity, breadth, or deviation from a familiar source). Participants could also share additional strategies not listed.

Generating statements

A few weeks following the first group discussion, a new group of stakeholders was invited for the subsequent session. Some of them had attended the first session while the rest joined for the first time, as many of the participants from the first session were not available to participate in this session. First, participants were presented with the implementation strategies generated from the earlier session and a summary of the participants’ comments. Then, a group discussion was conducted where participants further discussed the details and issues pertaining to each proposed strategy. All feedbacks received (e.g. strategies where alternate definitions were proposed, strategies where comments only concerning modifications or addenda to ancillary material) were used to construct a final list of strategies or statements detailing what is required for person-centered practice at the organizational level for the rating process in the subsequent sessions.

Sorting and rating of statements

In the sorting phase, participants were asked to sort all the statements into groups based on thematic similarity. Participants were permitted to create as many or as few groups as they wished and sort the statements based on any desired criteria. The plotted statements were then discussed in groups moderated by the authors. The final list of statements was chosen by group consensus that maintained thematic consistency within each category. In the same session, participants were instructed to rate and comment on each statement on two criteria: importance and feasibility. Ratings were based on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘not at all important’ and ‘not at all feasible’ to ‘extremely important’ and ‘extremely feasible’.

Analyzing and mapping data into clusters

All findings were compiled and exported into R-CMap software; an application utilized to create concept maps from the sorted and grouped statements [Citation36]. This open-source software is implemented for R, of which version 3.5.1 was used. Data were organized into a 16 × 16 similarity matrix for each participant, which denoted whether a pair of statements had been grouped. An overall similarity matrix was constructed by summing the matrices for all participants. Multidimensional scaling visualized relationships between statements by plotting them in two-dimensional plots to produce a conceptual map. Clusters of ideas were generated among the plotted statements with hierarchical cluster analysis. Four clusters were generated by inspecting the dendrogram produced using hierarchical clustering. The average importance values for each cluster were calculated based on the importance rating of the underlying ideas. A computed stress value indicates the goodness of fit of the configuration, with lower stress values having a better fit [Citation33]. Previous analyzes of concept mapping reliability suggest that the average stress value could range from 0.155–0.352 [Citation37].

Generating go-zones

Finally, a go-zone analysis was conducted for each cluster to understand the relative ratings of statements [Citation33]. Go-zones are bivariate X-Y graphs of ratings, shown within quadrants constructed by dividing above or below the mean for both importance and confidence ratings. Statements in the upper-right quadrant (high importance and high feasibility) represent the most actionable ideas within each cluster.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the authors’ institutes. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

In total, 22 participants (17 women and five men) from the healthcare manager groups were involved in developing the concept map activities (). Some participated in both first and second group discussions, while the rest attended either one of the sessions. In small focus groups of up to 5 members, twelve managers provided a set of related concepts and strategies, while 17 recruited managers rated the importance and feasibility of the implementation strategies. Participants were healthcare managers with medical, nursing, or allied health practitioners’ backgrounds. They had direct experience managing acute and community health care practices within their organizations.

Table 1. Participant background.

The concept map

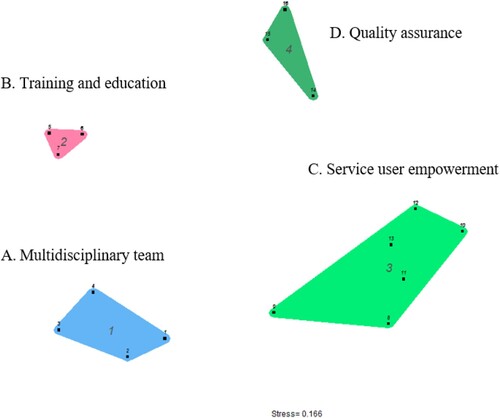

Sixteen statements () were located into a two-dimensional point map with a stress value of 0.166. Four distinct concepts were identified through multidimensional scaling and hierarchical analysis, which showed degrees of interrelation. These concepts are multidisciplinary teams, training and education, patient empowerment, and quality assurance (). The cluster names represent the statements within each cluster, encompassing participants’ understanding of person-centered practice requirements. The multidisciplinary team cluster represented creating and maintaining a team of professionals from various disciplines who work together to provide comprehensive care by developing and implementing treatment plans that address individuals’ physical, emotional, and social needs. The training and education cluster represented the importance of ongoing training and education for healthcare providers to keep their knowledge and skills up-to-date. This may involve continuing education courses, professional development programs, or other forms of training that help healthcare providers stay current with the latest research and best practices in their field. The service user empowerment cluster represented the involvement of service users in their care and empowering them to take an active role in the decision-making process. This may involve providing service users with information about their condition, treatment options, and self-care strategies, as well as encouraging them to ask questions and express their preferences and concerns. The quality assurance cluster represented the importance of ensuring that healthcare services are delivered in a safe, effective, and efficient manner. This may involve monitoring and evaluating the quality of care provided, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing measures to enhance the overall quality of care.

Figure 2. Conceptual map of organizational strategies in promoting person-centered care generated through multidimensional scaling and hierarchical analysis. The numbers in the bigger font represent the clusters, while the smaller font numbers are the statements.

Table 2. Summary of the implementation statements, organized by cluster with mean importance and feasibility ratings.

Rating

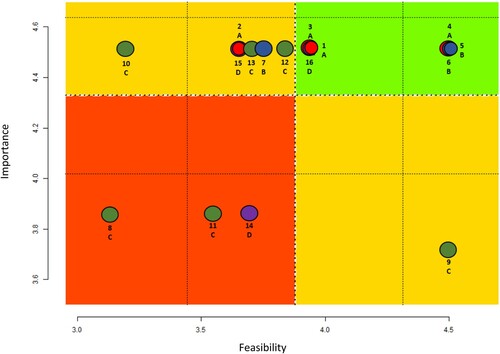

In the rating phase, participants were instructed to rate each of the statements from the brainstorming phase on a Likert scale of 1–5, on two criteria: (i) importance, ranging between 3.70–4.50 (overall mean 4.33); and (ii) feasibility, ranging between 3.15–4.50 (overall mean 3.87). For importance, individual statements received a minimum mean value (3.70) above the halfway point of three on the scale, indicating no statement was considered unimportant, which further validated our statement list.

Go-zones of importance and feasibility

Go-zones were generated for all clusters (). The figure shows how the statements [Citation1–15, Citation38] within the clusters (A – D) rated importance versus feasibility. This visual representation allows statements to be placed in four quadrants: high importance and high feasibility; high importance and low feasibility; low importance and high feasibility; and low importance and low feasibility. The go-zones demonstrated that statements 4, 5, and 6 on creating new necessary activities, training on the importance of person-centeredness, and having person-centered skills were rated above the mean for importance and feasibility. Training programs focusing on specific communication, cultural competence, and interpersonal skills can increase trust and awareness of the patient's agenda. This can lead to better patient engagement, improved patient outcomes, and increased patient satisfaction. A training program for doctors and nurses emphasizing patient-centered care, with visual agenda charts and readiness to change behavior, can help promote person-centeredness. The training can help healthcare providers understand the importance of patient-centered care and equip them with the necessary tools to deliver care that meets service users’ needs and preferences. This may be supplemented by creating new professional activities, such as telemedicine, shared consultation, and a shared home visit, which can help expand access to care and improve service user engagement, particularly for those unable to travel to a healthcare facility. In contrast, statement 8 on access to resources for self-empowerment received the lowest rating in both importance and feasibility. Depending on the type of resources being provided, there can be concerns about sharing service users’ health information, which results in the hesitance to provide access to health records or other sensitive information without a clear understanding of the legal and ethical implications. Additionally, statement 9 on providing psychosocial support to improve service users’ self-care was rated as having low importance but high feasibility, while statement 10 on providing patients with decision aids and a workbook to discuss essential issues during visits was regarded as high importance but low in feasibility. Healthcare providers may feel that providing access to resources for service users’ self-management would require more time and resources than they have available. They may already feel stretched thin with their current workload, and adding more tasks could be considered as burdensome.

Discussion

In this study, we harnessed the experience and views of healthcare managers to create a conceptual map on organizational strategies in promoting person-centered practice in Malaysia. We found 4 clusters of strategies fundamental to person-centered practice and culture development, which were 1) the need for a multidisciplinary team; 2) providing training and education to healthcare providers; 3) service user empowerment; and 4) quality assurance measures, with statements in each cluster further rated in terms of their importance and feasibility for implementation. The stress value in the concept map is within the range, indicating an acceptable fit between the raw sorting data and the two-dimensional configuration [Citation39].

This finding supports the discussion on prioritization in transforming person-centered theory into practice. While the clusters provide a comprehensive overview of transformation areas important to drive changes in organizational person-centered practice, the rating on importance and feasibility offers more detailed information on where the focus and effort should begin and delineate areas for short and long-term development. We found branching professional activities to cover a more comprehensive spectrum of services and training healthcare providers on person-centered competency were rated as the most important and feasible strategies. Branching professional activities, including harnessing technology, would make care management more effective and reduce the time to deliver certain services or programs [Citation40, Citation41]. However, it needs to be balanced with additional resources to avoid piling burden and increasing workload to healthcare providers juggling many different tasks.

Similarly, training healthcare providers to be more competent in delivering person-centered practice may seem easier to achieve. Still, it should be supported by systems’ management that allows them ample time and opportunity to deliver the practice. Studies demonstrated that lack of time, high workload, and understaffing are barriers to delivering person-centered practice that need to be addressed [Citation42, Citation43]. The training should also aim to equip healthcare workers with an in-depth understanding of the importance of person-centered practice. Busetto and colleagues, in their study, reported that the top barriers in the translational practice of person-centered care were often associated with a lack of support and resistance by healthcare providers who view the practice as a time-consuming innovation and underappreciate the relevance [Citation44].

On the other spectrum, empowering service users for self-management by providing decision aids and workbooks to assist them in discussing important issues with healthcare providers were deemed important but least possible. Empowering service users, caretakers, and the community are fundamental in many person-centered governing frameworks [Citation5–7]. Unvoiced needs happen when a user's concern is not called out or addressed while receiving care [Citation45]. It reinforces the centrality of productive collaborative relationships, involving constant information exchanges between servicer users, healthcare providers, managers, and educators [Citation46]. However, based on our findings, this strategy was seen as challenging to be implemented comprehensively in Malaysia, possibly due to a lack of effective decision aids and insufficient time for the healthcare providersto explore users’ or carers’ concerns in detail. Due to the high workload in organizations, many previously reported they only had enough time to address the main presenting symptoms [Citation47]. Unfortunately, these unvoiced needs that are not called out for or addressed may affect treatment care plan and satisfaction towards the consultation [Citation45, Citation48]. Efforts to accommodate this issue must be addressed through strategic planning development of the organization.

It is also of value to highlight the strategies in the least important and least feasible quadrant. The strategies include enabling service usersaccess to resources for self-management such as their laboratory test results and involving users in checking the accuracy of information and care management plans. While allowing these strategies to take place seems straightforward, participants had raised the issue of previous cases whereby patients or their family members took legal action against healthcare providers when mistakes were noticed. Although this finding inclined towards providers’ interest due to the nature of the study exploring the perspective of managers, the ethic in balancing between service user empowerment and enabling providers to do so in a conducive way must be considered and a guiding principle respecting and protecting the rights of both parties must be prepared and adhered [Citation49, Citation50].

These organizational strategies will only materialize once the governing system adopts and strengthen existing practice. Person-centeredness, transformational leadership, and organizational readiness were considered separate attributes necessary for workplace cultural change [Citation51]. Thus, the findings of this study will allow the potential stakeholder roles and responsibilities and areas for prioritization to be visible. The collection for further stakeholder-specific rating data will aid understanding for each group within the healthcare system for shared action and responsibility. The mapping also addressed a critical gap encompassing systems and education perspectives to achieve person-centered practice. Rating the importance and feasibility of strategies will likely assist in developing a strategic plan encompassing immediate and long-term approaches.

The study’s strength relies on the findings that inform future research on person-centered practice and the identified gaps in current knowledge. The recommended best practices could be applied in other contexts or settings and are considered especially valuable for international researchers interested in implementing person-centered care in their healthcare systems or even developing more effective approaches to person-centered care. In addition, the cultural factors provided valuable insights for understanding how cultural differences impact healthcare practices. The involvement of organization managers encourages the generation of ideas on the requirement for person-centered practice based on their experience being involved in the organization’s governing system. However, this may have limited the requirement towards fulfilling providers’ needs instead of service users’ and carers’ needs as this study did not explore their point of view. Nevertheless, triangulating current findings with future rating data from a broader participant group will be beneficial to assess implications and outcomes. Exploring patients’ and carers’ perspectives and their role in improving person-centred practice is therefore a valuable future research area. The sampling strategy is likely to have resulted in greater participation of advocates for person-centered care; however, we believe this is appropriate for research involving the generation of the conceptual map. The participant numbers for ratings were also insufficient to represent the ratings of the stakeholder groups reliably. It should be highlighted that some participants either attended only one or both discussion sessions in the study. The participants who attended both sessions may have formed some ideas not apparent to other participants who only attended once and may have influenced the findings. Furthermore, the ideas generated and the ranking activity may change in the future, depending on the evolution of the healthcare systems’ principles and practices. Nevertheless, this activity provided valuable basis to understand organizational requirements for person-centered practice’s transformation. As such, exploring similar objectives among a more extensive group of stakeholders is desirable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, involving service users in developing short and long-term strategic plan for person-centered transformational practice is crucial for ensuring that the plan reflects the needs and preferences of the people receiving care. However, for service users to be given the opportunity to participate in the planning process, organizational managers need to understand the importance of service user involvement and create a platform for them to share their experiences and opinions. This may require a shift in organizational culture and the development of new communication channels to enable effective and meaningful participation from service users. In presenting the conceptual map, we have focused the current debate on areas for prioritization and challenges that must be addressed for stakeholders to ensure person-centered practice progress comprehensively in formulating a sustainable, long term person-centered culture. Further research is needed to explore how best to involve service users in developing strategic plans, and to provide guidance for healthcare providers and organizational managers on effective strategies for service user involvement.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to declare our gratitude to the Director-General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia (KKM/NIHSEC/P18-766(14)), and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (2018-14363-19627).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pui San Saw

Pui San Saw holds a Master of Science in Medical and Health Sciences and Bachelor of Pharmacy. She is a registered pharmacist and lecturer at the School of Pharmacy, Monash University Malaysia. Her teaching and research interests lie in social and administrative science, primary care, and public health.

Nur Zahirah Balqis-Ali

Nur Zahirah Balqis-Ali holds a Bachelor of Medicine degree. She is a registered medical officer at the Institute for Health Systems Research, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Her research interests are in the area of primary care and aging, with a preference for system dynamic simulation of healthcare services.

Kia Fatt Quek

Kia Fatt Quek holds a PhD from the University of Malaya. He is an Associate Professor in Community Health at the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia. His research interest is public health, particularly the epidemiology of non-communicable and communicable diseases.

Badariah Ahmad

Badariah Ahmad holds a PhD (Monash Aus) and MBBS (Ireland) from the Royal College of Surgeons. She is a Senior Lecturer at the Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia. Her research interest is Non-Communicable Diseases, diabetes education, metabolic Syndrome, and Vitamin E.

Weng Hong Fun

Weng Hong Fun holds a PhD and is the head of the Centre for Health Systems Outcomes at the Institute for Health Systems Research Malaysia. His research interest is general health outcomes in communicable and non-communicable diseases using the decision tree model, dynamic transmission model, and discrete event simulation.

Sondi Sararaks

Sondi Sararaks is a Public Health Specialist and the Director of the Institute for Health Systems Research. She holds a Master's of Community Health and an MBBS. Her research works are in the area of health systems, including health outcomes, services, and policy development.

Shaun Wen Huey Lee

Shaun Wen Huey Lee holds a PhD and is a professor at the School of Pharmacy, Monash University Malaysia. He is a registered pharmacist and health systems researcher with an interest in health policy and systems research in low-resource settings.

References

- World Health Organization. People-centered health care: a policy framework 2007. Geneva: Switzerland; 2014.

- De Silva D. Helping measure person-centred care: a review of evidence about commonly used approaches and tools used to help measure person-centred care. Health Foundation; 2014.

- Morgan S, Yoder LH. A concept analysis of person-centered care. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(1):6–15.

- Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(9):e107828.

- González-Ortiz LG, Calciolari S, Goodwin N, et al. The core dimensions of integrated care: a literature review to support the development of a comprehensive framework for implementing integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(3).

- McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centred nursing: theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Geneva: World Health Organization 2019; 2016.

- Shaller D. Patient-centered care: what does it take? New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2007.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Continuity and coordination of care: a practice brief to support implementation of the WHO Framework on integrated people-centred health services.

- McCormack B, Borg M, Cardiff S, et al. (2015). Person-centredness-the'state'of the art.

- World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. World Health Organization; 2015.

- West MA, Chowla R. Compassionate leadership for compassionate health care. Compassion: Routledge; 2017. p. 237-257.

- Rosa W, Fitzgerald M, Davis S, et al. Leveraging nurse practitioner capacities to achieve global health for all: COVID-19 and beyond. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67(4):554–559.

- Watson M, Ferguson J, Barton G, et al. A cohort study of influences, health outcomes and costs of patients’ health-seeking behaviour for minor ailments from primary and emergency care settings. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2):e006261.

- Amin M, Till A, McKimm J. Inclusive and person-centred leadership: creating a culture that involves everyone. Br J Hosp Med. 2018;79(7):402–407.

- Kirkley C, Bamford C, Poole M, et al. The impact of organisational culture on the delivery of person-centred care in services providing respite care and short breaks for people with dementia. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(4):438–448.

- Dowling S, Manthorpe J, Cowley S. (2006). Person-centred planning in social care: a scoping review.

- Economic Planning Unit. Ninth Malaysia Plan 2006-2010. Kuala Lumpur: Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad; 2006:490-498.

- Family Health Development Division. Garis Panduan Pelaksanaan Konsep Doktor Keluarga di Klinik Kesihatan. Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2016.

- Thuraisingam AS, Kanagasabapathy SV. (2019). Patient Centred Decision Making in Healthcare in Malaysia.

- Hazarika I. Health workforce governance: key to the delivery of people-centred care. Int J Healthc Manag. 2021;14(2):358–362.

- Ng C-J, Lee P-Y, Lee Y-K, et al. Official statistics and claims data records indicate non-response and recall bias within survey-based estimates of health care utilization in the older population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–7.

- Lee YK, Ng CJ, Lee PY, et al. Shared decision-making in Malaysia: legislation, patient involvement, implementation and the impact of COVID-19. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen. 2022;171:89–92.

- Khuan L, Juni MH. Nurses’ opinions of patient involvement in relation to patient-centered care during bedside handovers. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2017;11(3):216–222.

- Ali A, Meyer C, Hickson L. Patient-centred hearing care in Malaysia: what do audiologists prefer and to what extent is it implemented in practice? Speech Lang Hearing. 2018;21(3):172–182.

- Ambigapathy R, Chia YC, Ng CJ. Patient involvement in decision-making: a cross-sectional study in a Malaysian primary care clinic. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010063.

- Haynes SC, Rudov L, Nauman E, et al. Engaging stakeholders to develop a patient-centered research agenda: lessons learned from the research action for health network (REACHnet). Med Care. 2018;56(10 Suppl 1):S27.

- Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):510–515.

- Leyns CC, De Maeseneer J, Willems S. Social health insurance contributes to universal coverage in South Africa, but generates inequities: survey among members of a government employee insurance scheme. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:1–14.

- Rudawska I. Concept Mapping in developing an indicator framework for coordinated health care. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;176:1669–1676.

- Vaughn LM, Jones JR, Booth E, et al. Concept mapping methodology and community-engaged research: a perfect pairing. Eval Program Plann. 2017;60:229–237.

- Willis CD, Mitton C, Gordon J, et al. System tools for system change. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):250–262.

- Kane M, Trochim WM. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications, Inc; 2007.

- Trochim W, Kane M. Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(3):187–191.

- LaNoue M, Mills G, Cunningham A, et al. Concept mapping as a method to engage patients in clinical quality improvement. Ann Family Med. 2016;14(4):370–376.

- Bar H, Mentch L. R-C map–an open-source software for concept mapping. Eval Program Plann. 2017;60:284–292.

- Trochim W, editor. (1993). The reliability of concept mapping. Annual conference of the American Evaluation Association.

- van Diepen C, Fors A, Ekman I, et al. Association between person-centred care and healthcare providers’ job satisfaction and work-related health: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042658.

- Rosas SR, Kane M. Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(2):236–245.

- Patricio L, Sangiorgi D, Mahr D, et al. Leveraging service design for healthcare transformation: toward people-centered, integrated, and technology-enabled healthcare systems. J Serv Manage. 2020.

- Phanareth K, Vingtoft S, Christensen AS, et al. The epital care model: a new person-centered model of technology-enabled integrated care for people with long term conditions. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(1):e6506.

- Bhattacharyya KK, Craft Morgan J, Burgess EO. Person-centered care in nursing homes: potential of complementary and alternative approaches and their challenges. J Appl Gerontol. 2021: 07334648211023661.

- Kloos N, Drossaert CH, Trompetter HR, et al. Exploring facilitators and barriers to using a person centered care intervention in a nursing home setting. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2020;41(6):730–739.

- Busetto L, Luijkx K, Calciolari S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to workforce changes in integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18(2).

- Low LL, Sondi S, Azman AB, et al. Extent and determinants of patients’ unvoiced needs. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011;23(5):690–702.

- Bhoomadevi A, Ganesh M, Panchanatham N. Improving the healthcare using perception of health professional and patients: need to develop a patients centered structural equation model. Int J Healthc Manag. 2021;14(1):42–49.

- Sellappans R, Lai PSM, Ng CJ. Challenges faced by primary care physicians when prescribing for patients with chronic diseases in a teaching hospital in Malaysia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e007817.

- Zailinawati A, Ng CJ, Nik-Sherina H. Why do patients with chronic illnesses fail to keep their appointments? A telephone interview. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2006;18(1):10–15.

- Hebert PC. Disclosure of adverse events and errors in healthcare. Drug Saf. 2001;24(15):1095–1104.

- Webb K. Exploring patient, visitor and staff perspectives on inpatients’ experiences of care. J Manage Marketing Healthcare. 2007;1(1):61–72.

- Manley K, Sanders K, Cardiff S, et al. Effective workplace culture: the attributes, enabling factors and consequences of a new concept. Int Pract Dev J. 2011;1(2):1–29.