ABSTRACT

In this contribution, I explore the legal implications associated with information deficits relating to intra-Community (EU) trade in goods. The ultimate purpose of this contribution is to establish to what extent taxable persons forming part of an intra-Community supply chain should be confronted with legal implications such as VAT assessments and fines whenever they are subject to an information asymmetry which prevents them from applying VAT in line with the legal requirements. Firstly, in Section 2 of this contribution, I define the concept of ‘information asymmetry’ and apply it to the context of (EU) VAT. In Section 3, I explore the legal implications of information asymmetries in intra-Community trade in goods, and further address the question to what extent the taxable person should be confronted with them. Finally, in Section 4, I provide explore various remedies that may contribute to the structural reduction of information asymmetries in practice.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Since the abolition of its internal customs frontiers in 1993, the European Union has employed a specific VAT regime for the taxation of business-to-business (B2B) supplies of goods which are transported from one Member State to the other.Footnote1 Under this ‘intra-Community VAT regime’, taxable persons forming part of an intra-Community supply chain depend on each other for a proper exchange of information as regards various determinants of taxation—including the transport trajectory of the goods and the VAT status of others within the chain.

In case information is not properly exchanged, a taxable person within an intra-Community supply chain may not be able to apply VAT to his transactions in accordance with the legal requirements. Consequently, that person may be confronted with VAT assessments, fines and other sanctions. In this contribution, I explore the legal implications associated with ‘information asymmetries’ arising in the context of intra-Community trade in goods. The purpose of this contribution is to establish to what extent a taxable person is and should be confronted with legal implications (e.g. VAT assessments and fines) whenever he does not have access to information which is held by others within the intra-Community supply chain.

Firstly, in Section 2 of this contribution, I define the concept of ‘information asymmetry’ and apply it to the context of (EU) VAT. In Section 3, I explore the legal implications of information asymmetries in intra-Community trade in goods, and further address the question to what extent the taxable person should be confronted with them. Finally, in Section 4, I provide explore various remedies that may contribute to the structural reduction of information asymmetries in practice. Further, I discuss the revised intra-Community VAT regime, as envisaged by the European Commission, to see to what extent it will facilitate the information position of the taxable person.

2. The concept of information asymmetry

As indicated in the introduction, this contribution centres on the phenomenon of information asymmetries within the context of EU VAT. It therefore requires a definition of the concept of ‘information asymmetry’—a subject addressed in Sections 2.1 and 2.2. In Section 2.3, I relate the concept to positive EU VAT law, providing various examples which illustrate the materialisation of an information asymmetry in practice.

2.1. A definition of ‘information asymmetry’ derived from economics and game theory

The concept of information asymmetry is most commonly employed to describe a situation in which there is a discrepancy of information between multiple interacting parties. Wang et al., as well as Clarkson et al., state that an information asymmetry exists ‘when a party or parties possess greater informational awareness pertinent to effective participation in a given situation relative to other participating parties’.Footnote2 Conversely, Birchler and Bütler define the concept as a situation in which there is ‘a difference in information between the two sides in a contract’, whereas Dawson et al. relate it to the circumstance that ‘one party has more knowledge (tacit or explicit) than the other party’.Footnote3

The concept of information asymmetry is prominently used in the field of economics, often with the purpose of establishing the economic impact of the (un)availability of relevant information on the functioning of markets.Footnote4 It is also employed in game theory, a field of science which involves the (mathematical) study of strategic interactions between independent actors who are engaged in decision making processes.Footnote5 Further to its use in these fields, an information asymmetry is a key notion in connection with the so-called ‘principal-agent problem’, which concerns the possible relational hazard that follows from the circumstance that an acting party (i.e. the agent) has better information than the party on whose behalf he is supposed to act (i.e. the principal).Footnote6 In that context, the asymmetry is employed to denote the unequal standing of the parties as far as (access to) information is concerned.

The interdisciplinary and divergent use of the concept of information asymmetry implies that it is often semantically adapted to the specific needs and nuances of particular research subjects or niches. As such, it lacks a uniform definition. Even though the concept is occasionally employed in the context of law (e.g. by StrahilevitzFootnote7, ReardonFootnote8, and KarkkainenFootnote9), it is important to stress that no (legal) definition can be derived from EU law.Footnote10 Notwithstanding this, EU law does include legislation which is (often implicitly) aimed at reducing information asymmetries or the adversities associated with them. An example is the Market Abuse Directive (2003/6/EC), following which persons are, inter alia, not allowed to engage in transactions on the basis of ‘inside information’ that is not publicly available.Footnote11 Additionally, in the context of EU VAT, a prominent piece of legislation which is essentially aimed at the reduction of information asymmetries between the tax authorities of the Member States concerns the Regulation on Administrative Cooperation (904/2010).Footnote12 These examples illustrate that (fiscal) information as such may very well be the focus of legislative efforts.

2.2. A definition of ‘information asymmetry’ tailored to EU VAT

The concept of information asymmetry is central to the research aims of this contribution. Since a uniform legal definition is non-existent, I employ the following definition of an information asymmetry: a situation in which one party has (or can access) information that another party does not have (or cannot access), but which is required by the latter in his capacity as taxable person and with regard to his VAT obligations.Footnote13

The above definition centres on the presence of an information deficit at the level of the taxable person in the context of his VAT obligations. The asymmetry of information presupposes not only the initial availability of the information to others (e.g. transaction counterparties, tax authorities), yet also its relevance for the taxable person who is held to apply VAT to his transactions. Thus, as regards the initial availability, the concept excludes situations in which tax information is non-existent. This is for example the case when a taxable person effects an intra-Community supply of goods to another taxable person who has failed to register for VAT purposes in the Member State of arrival of the goods.Footnote14 In the latter situation, which reflects the case facts in VSTR Footnote15, the taxable person (supplier) lacks certain information (i.e. the VAT identification number of the customerFootnote16) which he nonetheless requires for VAT purposes (i.e. for his recapitulative statementFootnote17, and in order to draft an invoice in conformity with the invoicing obligationsFootnote18). However, since the customer did not register for VAT purposes, the information is non-existent and not held by others—implying that this situation does not involve an information asymmetry.Footnote19 Additionally, as regards the criterion relevance, the concept of information asymmetry presupposes that the availability of the respective information has, or can have, an influence on the legal position of the taxable person in the context of his VAT obligations. In the mentioned example, a relevant item of information which may constitute the object of an information asymmetry concerns the physical transport trajectory of the goods supplied. In case the taxable person has the respective information in the proper form, he may apply the exemption for intra-Community supplies.Footnote20 Conversely, in case he does not have the information in the proper form, he is not able or allowed to apply the exemption.Footnote21 provides an elementary explanation of the various elements inherent to a horizontal information asymmetry between a taxable person and his transaction counterparty.

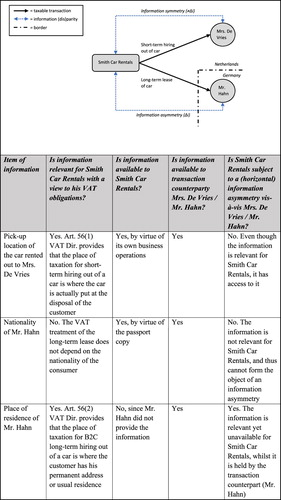

Figure 1. Case study: Smith Car Rentals, established in the Netherlands, rents out a car to Mrs De Vries for five days. Mrs De Vries picks up the car in Maastricht, the Netherlands. In the same month, Smith Car Rentals enters into a long-term business-to-consumer (B2C) car lease (rental) with Mr Hahn. Mr Hahn provides a copy of his passport in advance. However, when signing the contract at the premises of Smith Car Rentals, Mr Hahn does not fill out his place of residence details (Aachen) because of privacy concerns that he has.

2.3. The origin and consequences of information asymmetries in EU VAT

This contribution studies the occurrence of information asymmetries in EU VAT. In support of its relevance, a necessary exercise in this respect is to establish not only the structural origin of asymmetries (Section 2.3.1), yet also the (adverse) consequences associated with them (Section 2.3.2).

2.3.1. The origin of information asymmetries in EU VAT

Information asymmetries are a structural implication of the EU VAT system. Their potential occurrence follows from the framework of statutory (EU) VAT law, which creates a need for exogenous information at the level of the taxable person who is held to apply VAT to his transactions. More specifically, the possibility of information asymmetries follows from the (partly) external nature of the object of taxation.Footnote22 EU VAT aims to burden consumption by private individuals, employing the (taxable) transaction as an approximation of that consumption.Footnote23 Yet as the object of taxation, the transaction is an event which is, at least partly, influenced and defined by the transaction counterparty. Taking this into account, the possibility of information asymmetries follows from the circumstance that the rules on taxation (e.g. rules on exemptions, the place of supply) are often based on, or connect directly to, aspects of the transaction which are external from the perspective of the taxable person. In the case study concerning the car rental company (see ), an example of such an external aspect is that the place of supply for long-term hiring out of means of transport depends on where the customer (being a non-taxable person) has his permanent address or usually resides—information which is initially external to the taxable person hiring out the car.Footnote24 The corresponding information need of the taxable person inherently holds the risk of asymmetries.

In this context, it should be noted that the materialisation of an information asymmetry is not a certainty. In case of an information deficit, the taxable person may be able to obtain access to the required information on the basis of his commercial relationship with his transaction counterparties.Footnote25 Additionally, various items of information may even be publicly available.Footnote26 It is however no certainty that the taxable person is able to procure all necessary information in a timely fashion. Transaction counterparties may provide incomplete or no information at all, e.g. because of privacy reasons or when mutual relations have deteriorated because of a commercial conflict. Transaction counterparties may even decide to disclose false information purposefully, especially when such a course of action may reduce their economic sacrifices in connection with the transaction.Footnote27 The fact that information asymmetries regularly surface in cases brought before the CJEU underlines the relevance of their occurrence in practice.

2.3.2. The (adverse) consequences of an information asymmetry

In general terms, the materialisation of an information asymmetry can be said to disrupt the levy of VAT in a multifold manner. Reverting back to the example involving the long-term car lease, the information asymmetry (Δi) between the car rental company (Smith Car Rentals) and the customer (Mr Hahn) prevents the former from complying with the legal VAT requirements. In first instance, Smith Car Rentals may spend considerable efforts and resources to establish the place of residence of the customer—a circumstance which is at odds with the principle of effectiveness.Footnote28 If the car rental company proves unable to obtain access to the information, the Netherlands may unilaterally claim taxing competence and demand the payment of (Dutch) VAT.Footnote29 Further, it is not unthinkable that also Germany, being the Member State in which Mr Hahn actually resides, simultaneously claims taxing competences—implying the risk of double taxation.Footnote30 To the extent that the car rental company has not remitted VAT in both Member States, it is additionally exposed to the risk that national tax authorities impose fines and other sanctions.Footnote31

Further, at this point, it becomes evident that the materialisation of an information asymmetry may indeed prevent the car rental company from applying VAT to the lease transaction in line with the objective characteristics of that transaction. Such a deviant VAT treatment is contrary to the CJEU’s notion that taxation is to be based on objective parametersFootnote32, and that similar supplies of goods or services, which are thus in competition with each other, are treated equally for VAT purposes.Footnote33 In sum, information asymmetries impede the uninterrupted, efficient and neutral levy of VAT. Since this is particularly apparent in cross-border settings, and directly opposed to the promotion of the EU’s internal market, the following section discusses the materialisation of asymmetries in the particular context of intra-Community trade flows.

3. The materialisation of information asymmetries in intra-Community B2B trade

The previous sections of this contribution related to VAT information asymmetries in a general manner. In this section, I discuss the phenomenon of information asymmetries within the specific context of intra-Community business-to-business (B2B) trade in goods. The primary reason for this is that the positive VAT law on intra-Community trade—in particular, the exemption for intra-Community supplies of goods ex article 138(1) of the VAT Directive—relies on determinants which are largely external to the taxable person carrying out the supply.

Following this introduction, I firstly provide an overview of the current intra-Community VAT regime for trade in goods (Section 3.1). Subsequently, limiting myself to the perspective of the supplier, I discuss information asymmetries in connection with the VAT status of the customer (Section 3.2), the occurrence of the cross-border transport (Section 3.3), and the allocation of the cross-border transport (Section 3.4).

3.1. An overview of the current intra-Community B2B VAT regime

In late 1991, the EU institutions settled on the adoption of an intra-Community VAT regime which was based on the destination principle.Footnote34 Under the regime, which is still in place today, the supplier of the goods applies an exemption to his supply, whilst enjoying a right of deduction of VAT on related costs.Footnote35 In turn, the purchaser, who obtains the right to dispose of the goods, carries out a taxed intra-Community acquisition in the Member State where the transport of the goods ends.Footnote36 The transaction is thus subject to taxation in the Member State where the transport of the goods ends. Following the reporting obligations of both parties, the tax authorities on both sides of the EU border are able to administratively monitor intra-Community trade flows between taxable persons, even without the presence of physical border checks.Footnote37

From the perspective of the person supplying the goods (i.e. supplier), the intra-Community VAT regime implies a considerable need for information to be obtained from the transaction counterparty. This is primarily the consequence of the fact that the CJEU has held that it is for the supplier of the goods to furnish the proof that the conditions for the application of the exemption for intra-Community supplies are fulfilled (burden of proof).Footnote38 In addition, in the context of intra-Community trade, the supplier requires certain items of information to fulfil specific reporting obligations (i.e. filing the recapitulative statement) and invoicing obligations.Footnote39 The following sections discuss the most prominent items of information, and discuss to what extent the (legal) position of the supplier is affected in case these items constitute the object of an information asymmetry.

3.2. Information asymmetries as regards the VAT status of customers

Amongst other determinants, the application of the intra-Community VAT regime is dependent on the VAT status of the customer. That person needs to be a person whose intra-Community acquisitions are subject to VAT on the basis of articles 2(1)(b) and 3 of the VAT Directive (hereafter: ‘qualifying VAT person’).Footnote40 Moreover, EU legislation excludes from the regime, in simplified terms, intra-Community supplies of goods to a) agricultural enterprises subject to a special flat-rate scheme, b) taxable persons who carry out only supplies in respect of which VAT is not deductible, and c) non-taxable legal persons (assuming these categories of acquirers have not made use of the option to tax their acquisitions of goods).Footnote41 The detailed rules on these ‘excluded entities’ imply that the supplier must obtain very specific information on the VAT status and affairs of his customers if he is indeed to apply VAT in line with the legal requirements of the intra-Community VAT regime. Further, the fact that the information is first and foremost internal to the customer contributes to the risk of information asymmetries at the level of the supplier. It may, for example, be difficult for him to verify and substantiate with sufficient evidence that the customer is a taxable person who only carries out supplies in respect of which VAT is not deductible.Footnote42

In case of an information asymmetry as regards the VAT status of the customer, the taxable person effecting the supply of goods will not be able to demonstrate that the conditions for the exemption for intra-Community supplies have been met.Footnote43 Consequently, if the supplier nonetheless applies the exemption, he may be confronted with VAT assessments and other sanctions (e.g. fines) in the Member State of departure of the goods.Footnote44 In order to avoid these adversities, the supplier will likely choose to charge VAT irrespective of the actual VAT status of his customer.Footnote45 In case the customer is a qualifying VAT person, the information asymmetry thus leads to a VAT treatment which does not correspond to the objective characteristics of the transaction—a situation which is at odds with, amongst other, the principle of fiscal neutrality.Footnote46

Notwithstanding the above, there are some aspects which may (partly) mitigate the risk of information asymmetries as regards the VAT status of the customer. Firstly, assuming the supply indeed qualifies as an intra-Community supply irrespective of the asymmetry, the possibility of being charged with (non-deductible) VAT constitutes an incentive for the customer to resolve the asymmetry and disclose sufficient information on his VAT status (including his VAT identification number) to the supplier.Footnote47 Secondly, the EU legislator has adopted some rules which facilitate the information position of the supplier in case the customer is an excluded entity. In particular, article 4 of the VAT Regulation provides that such an entity will be treated as a qualifying VAT person in case he discloses his VAT identification number to the supplier in the context of an intra-Community supply of goods. Thus, the disclosure of the VAT identification number is an event which allows the supplier to presume that the customer is a qualifying VAT person—taking away the need to procure additional information from the latter.Footnote48 This instance of regulatory effort illustrates that legal presumptions carry the potential of facilitating the information position of the supplier (a subject discussed also in Section 4 of this contribution).

3.3. Information asymmetries as regards the occurrence of intra-Community transport

An important condition for the application of the intra-Community VAT regime is that the goods supplied must have been transported from one Member State to the other. Since information as regards the occurrence and transport trajectory of the goods may very well be the object of an asymmetry from the perspective of the supplier, I discuss this aspect to further detail in the following sections.

3.3.1. The Teleos judgment and the occurrence of intra-Community transport

The Teleos case concerns a taxable person who makes several supplies to a customer who picks up the goods in the United Kingdom under EXW Incoterms.Footnote49 The customer states that the goods will be transported to France and Spain, and in support thereof provides signed CMR consignment notes.Footnote50 The taxable person applies the exemption for intra-Community supplies, yet after some time it becomes apparent that various CMR consignment notes contain false transport information such as non-existing transport companies and incorrect destinations. At the time of the supplies, the taxable person was thus subject to an information asymmetry as regards the actual transport trajectory of the goods. On the ground that the goods have never left the United Kingdom, the tax authorities of that Member State deny the application of the exemption and impose VAT assessments on the taxable person.

In a lengthy judgment, the CJEU rejects the imposition of VAT assessments by the UK tax authorities. In support of its judgment, the Court amongst other refers to the principle of fiscal neutrality, following which ‘suppliers who effect transactions within a country are never liable to pay output tax, given that it is an indirect tax on consumption’.Footnote51 In addition, even though the CJEU reiterates that the objective of preventing tax evasion sometimes justifies stringent requirements as regards suppliers’ obligations, ‘any sharing of the risk between the supplier and the tax authorities […] must be compatible with the principle of proportionality’.Footnote52 With regard to this, the Court rules that a regime imposing the entire responsibility for the payment of VAT on suppliers does not necessarily safeguard the VAT system from fraudulent conduct by the transaction counterparties. Thus, in case a supplier acted in good faith and submitted evidence establishing, at first sight, his right to the exemption of an intra-Community supply of goods, the tax authorities cannot hold him to account for VAT on those goods where that evidence is subsequently found to be false.Footnote53

3.3.2. Critical analysis: an investigative responsibility for the taxable person

In my view, the Teleos judgment is notable because it implies that the taxable person cannot by default be held to account for VAT when mala fide transaction counterparties have intentionally created an information asymmetry that has led the former to apply an exemption for which the conditions were not met.Footnote54 Thus, following the legal principles, the CJEU bestows a certain extent of legal protection on the taxable person—assuming he has acted in good faith and has done everything which could reasonably be required of him to prevent or resolve the asymmetry.Footnote55 One may regard this judgment as an implicit recognition of the fact that statutory EU VAT law occasionally manoeuvres the supplier in an unacceptably strenuous information position, in particular when the transaction counterparty deliberately discloses misinformation which effectively prevents the supplier from complying with his VAT obligations. As the supplier is adversely affected by the conduct of others, the Teleos judgment arguably expresses a proportional approach to his legal position; to hold the supplier accountable for (mala fide) events beyond his own knowledge and control would not serve any legitimate purpose (i.e. the correct levy of VAT).Footnote56 A similar judicial approach can be found in the more recent judgment of the CJEU in Santogal, a case concerning the intra-Community supply of a new vehicle.Footnote57 Even though this case did not involve an information asymmetry as regards the transport trajectory of the goods, it reaffirms that the supplier enjoys a certain extent of legal protection when it turns out that the transaction counterparty was (potentially) engaged in mala fide fiscal conduct.

In connection with the Teleos judgment, Swinkels underlines the responsibilities of the taxable person making the supply. He states that the supplier is only shielded from VAT assessments in case he has taken every reasonable measure in his power to ensure that the intra-Community supply did not lead to his participation in evasion.Footnote58 I agree with him that the Teleos judgment does not relieve the supplier from his obligations to apply VAT and procure sufficient information to that end. On the contrary: the taxable person is subject to an investigative responsibility Footnote59—at least, if he desires to enjoy the legal protection provided for by the CJEU in Teleos and Santogal. In this regard, I note that the CJEU refers to the existence of an investigative responsibility in other judgments as well. For example, in Paper Consult, the CJEU provides that

by obliging the taxable person to carry out [a certain] verification, the national legislation pursues an objective that is legitimate and even imposed by EU law, namely that of ensuring the proper collection of VAT and the prevention of VAT evasion, and that such a verification can reasonably be required of an economic operator.Footnote60

it is not contrary to EU law to require a trader to take every step which could reasonably be required of him to satisfy himself that the transaction which he is carrying out does not result in his participation in tax evasion.Footnote61

The Teleos judgment reflects a strong connection with the principle of prohibition of abuse and evasion.Footnote62 In my view, the investigative responsibility of the supplier particularly comes to the foreground whenever (intra-Community) VAT fraud takes place somewhere within the supply chain.Footnote63 On various occasions, the CJEU has held that exemptions or deductions of input VAT can be denied to a taxable person in case that person knew, or should have known, that he was participating in a transaction involving VAT fraud or the evasion of VAT.Footnote64 Since such fiscal misconduct is not uncommon in intra-Community supply chains, it evidently underlines the critical role of information at the level of the taxable person.Footnote65 In case a bona fide and ‘reasonable’ supplier receives information from others which is suggestive of VAT fraud or evasion, he is subject to an investigative responsibility to verify or discredit the respective information.Footnote66 Should he choose not to fulfil this responsibility, he cannot safely rely on his application of VAT and may be confronted with VAT assessments and other sanctions. In this specific context, CJEU case law thus points out that not only the absence but also the presence of information (i.e. on fraudulent behaviour of others) can ultimately determine, depending on the circumstances at hand, whether the supplier is confronted with legal implications (e.g. a denial of the exemption for intra-Community supplies, fines and other sanctions).Footnote67

3.4. Information asymmetries as regards the allocation of intra-Community transport

As evidenced by CJEU case law, information asymmetries also materialise in the context of chain transactions. For the purposes of this contribution, I define a ‘chain transaction’ as a situation in which one or more goods are supplied multiple times (e.g. by taxable person A to taxable person B, and subsequently by taxable person B to taxable person C), whilst the respective goods are transported directly from the first supplier (i.e. party A) to the ultimate customer (i.e. party C).Footnote68

In EMAG, the CJEU has held that where two successive supplies of the same goods give rise to a single intra-Community transport of those goods, only one of these supplies can be taxed under the intra-Community VAT regime.Footnote69 This ruling implies that, in the context of chain transactions, the (intra-Community) transport of goods needs to be allocated or attributed to the supply with which it holds the strongest temporal and material link.Footnote70 As I will argue in the following sections, the requirement to allocate transport in situations involving chain transactions may expose the taxable persons forming part of the supply chain to a rather complex manifestation of information asymmetries.

3.4.1. The Euro Tyre (I) and Toridas judgments and the allocation of intra-Community transport

The CJEU has addressed the allocation of cross-border transport in Euro Tyre (I) and Toridas.Footnote71 Both cases involve similar situations. In simplified terms, party A supplies goods to party B, who subsequently supplies them onwards to party C. The goods are picked up by party B (or his representatives) at the premises of party A in the Member State of origin, and are transported directly to party C in the Member State of destination. Since there is a single intra-Community transport movement, only one of the two supplies can be taxed under the intra-Community VAT regime. In both cases, the tax authorities of the Member State of origin (i.e. where the transport commences) take the position that the second supply (i.e. by party B to party C) is to be regarded as taxable under the intra-Community VAT regime, since the transport is linked to that supply.Footnote72 Consequently, they impose VAT assessments on party A, who has applied the exemption for intra-Community supplies to his supply to party B.

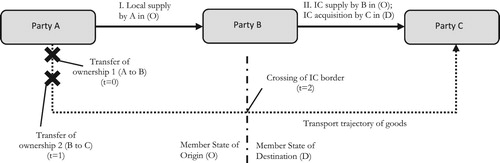

In both judgments, the CJEU essentially provides (in different wordings though) that the transport is to be ascribed to the first supply between party A and B in case the cross-border transport took place after the second supply.Footnote73 In my view, the logic behind this aspect of the Court’s doctrine is that if the second supply takes place whilst the goods are still in the Member State of origin, the ultimate intra-Community transport of the goods can, by definition, not take place, materially or temporally, in connection with the first supply.Footnote74 In both cases, and with a view to the objective characteristics of the transactions at hand, the ruling of the CJEU implies that party A has initially incorrectly applied the intra-Community VAT regime to its supply, which in principle is a taxed local supply (see ).

3.4.2. Critical analysis: the relevance of information in intra-community supply chains

The judgments of the CJEU in Toridas and Euro Tyre (I) strongly relate not only to the legal position of party A, yet also to his information position. In Toridas, the Court emphasises that party A was informed by party B that the goods would be resold immediately (i.e. before the cross-border transport) to party C. In fact, the referring court even states that party A ‘was aware of all the significant circumstances relating to the second supplies’.Footnote75 Thus, the supply chain knowledge of party A enabled him to, and should have led him to, qualify his own supply as a plain local supply in the Member State of origin; therefore, the tax authorities were correct in denying the exemption for intra-Community supplies.

Interestingly, the information position of party A in Euro Tyre (I) ultimately leads to a very different outcome than the one reached by the CJEU in Toridas. Instead of having ‘full information’ as regards the supply chain, party A in the Euro Tyre (I) case was not informed of the ultimate fate of the goods. In fact, party B provided its VAT identification number of the Member State of destination to party A and declared that the goods would be transported to that Member State in connection with the first supply.Footnote76 However, when the goods were supplied onward to party C before the intra-Community transport was effected, party B failed to immediately inform party A of these changed circumstances—leaving the latter subject to an information asymmetry as regards the ultimate fate of the goods.Footnote77 In its judgment, the CJEU recognises this aspect and even underlines that for the application of the exemption, the supplier (party A) ‘depends essentially on information that he receives for that purpose from the person acquiring the goods’.Footnote78 The Court continues by noting that since party B declared that the goods would be transported to another Member State and moreover provided his VAT identification number as issued by that Member State, party A was entitled to apply the exemptionFootnote79—notwithstanding the fact that party B transferred the ownership of the goods to party C before the intra-Community transport of the goods. In my view, this is a very notable outcome: the fact that party B disclosed information which led party A to falsely believe that he effected an intra-Community supply of goods, entitled party A to apply the exemption irrespective of the fact that the objective characteristics of the transaction do not support that application.

In connection with Euro Tyre (I) judgment, various scholars recognise the relevance of information as far as (intra-Community) supply chains are involved. Swinkels notes that party A is fully dependent on information received from party B, and points out that the CJEU recognises that that information is very limited in the case at hand.Footnote80 Amand suggests that by (not) disclosing information, party B effectively has the power allocate the transport to the supply of his choosing:

If the intermediary [party B] withholds information from the supplier [party A] that the goods were already onward supplied to the final customer [party C] at the moment of dispatch, the first supply can still be treated as an intra-Community supply.Footnote81

Irrespective of their interpretations, both these authors thus approach the allocation of transport from an informational perspective; by doing so, they in my view implicitly underline the distortive effect that information asymmetries may have in extended supply chains (e.g. legal uncertainty, unequal treatment of otherwise similar transactions).

In the context of Euro Tyre (I), Bal is even more outspoken. She notes that party A depends on the provision of information by party B; a circumstance which ‘increases […] [his] risk exposure’.Footnote82 Further, she argues that CJEU jurisprudence ultimately ‘puts [party] A in an awkward position: he needs to know where C receives the right to dispose of the goods and be sure that the goods are actually transported to another country, relying on information provided by others’.Footnote83 In line with the reasoning of these scholars, I am of the opinion that the critical complexity of the EU VAT system is, in this regard, that the VAT treatment of one supply within the supply chain cannot be established without sufficient information on one or more of the other supplies within the chain. Such a complexity is in my view constitutes a barrier to the efficient functioning of the VAT system.Footnote84 The primary reason for this is plain economic reality: often, parties within a supply chain are not informed on circumstances in other stages of the chain.Footnote85

3.4.3. Critical analysis: the rationale underlying the legal protection enjoyed by uninformed taxable persons

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the CJEU jurisprudence on intra-Community chain transactions validates the conclusion that the CJEU bestows a considerable extent of legal protection on parties who are, beyond their influence, subject to information asymmetries as regards the cross-border transport of the goods. Unfortunately, the CJEU is not very clear as regards the legal arguments or rationale underlying its notable judgment in Euro Tyre (I). Arguably, it is primarily the principle of proportionality which exerts influence in this regard.Footnote86 In my opinion, it would be disproportionate to allow the imposition of VAT assessments on a taxable person if his misapplication of VAT is effectively caused by the conduct (contract breach, failure to disclose information) of his customer over which he has no direct control. In such situations, and with a view to promoting the correct collection of VAT, sanctions should instead be imposed on the customer who has, by means of his conduct, frustrated the proper application of VAT. Even though no explicit reference is made to the principle of proportionality, this is exactly what the CJEU judgment comes down to in Euro Tyre (I) and Teleos: the Court rules that once the supplier has fulfilled his obligations relating to evidence of an intra-Community supply, where the contractual obligation to transport the goods out of the Member State of origin has not been satisfied by the person acquiring the goods, it is the latter who should be held liable for the VAT in that Member State.Footnote87 This is quite a far-stretching outcome, since such a VAT liability for the customer is without any legal basis in statutory EU VAT law.Footnote88 Nonetheless, I have sympathy for this approach, as it ultimately implies that the non-disclosing transaction counterparty is sanctioned for conduct that frustrates the efficient and neutral application of VAT.

When establishing the legal implications of information asymmetries, the central notion is that the CJEU attaches considerable weight to the normative dimension of the conduct of the parties forming part of the supply chain. A taxable person who has acted in good faith, and moreover has done everything which could reasonably be required of him to resolve the information asymmetry or prevent its materialisation, should in principle not be confronted with VAT assessments and other sanctions that follow from the incorrect application of VAT.Footnote89 Conversely, when a party (taxable person) has consciously or even intentionally frustrated taxation by creating or maintaining information asymmetries at the level of his transaction counterparties, it may very well be proportionate to impose sanctions on him—particularly when he has not acted in good faith and did not exert sufficient efforts to resolve or prevent the asymmetry. In my view, the advantage of this approach is that parties who form part of a (cross-border) supply chain experience an incentive to properly disclose relevant tax information throughout the chain; if they fail to do so, they may ultimately be held accountable for the payment of VAT.

4. An exploration of remedies against information asymmetries

The previous section of this contribution provided that CJEU case law bestows a certain extent of legal protection on taxable persons who are subject to an information asymmetry. However, CJEU case law may only mitigate the adverse legal symptoms of information asymmetries (e.g. fines, VAT assessments), whereas it fails to address the causes of their materialisation. In this section, I discuss some remedies against the materialisation of information asymmetries (Section 4.1). Further, I explore to what extent the revised intra-Community VAT regime as proposed by the Commission has the potential of facilitating the information position of the taxable person (Section 4.2).

4.1. Rebuttable presumptions and horizontal disclosure obligations

One option to reduce the materialisation of information asymmetries in practice is to impose horizontal disclosure obligations on the (taxable) person who holds the information. Currently, there are almost no rules in positive EU VAT law which regulate the flow of information between transaction counterparties.Footnote90 Nonetheless, such rules can be used to facilitate the information position of the taxable person who requires external information in the course of taxation. For example, in the context of pick-up supplies of goods, the EU legislator could oblige the taxable person who carries out or arranges the cross-border transport to disseminate (copies of) documentary evidence as regards that transport to the supplier.Footnote91 Even though such disclosure obligations require proper enforcement by the public authorities, and ultimately depend on compliance by the person to whom they apply, they can indeed promote the horizontal flow of information between transaction counterparties.Footnote92

Another option to reduce the materialisation of information asymmetries is to adopt (rebuttable) presumptions. (Rebuttable) presumptions are rules of positive law which can be employed to take away the need for the taxable person to obtain items of information which are difficult to access or substantiate.Footnote93 As such, the latter carry the potential of averting information asymmetries in practice. Exemplary in this regard are the various rebuttable presumptions which the EU legislator adopted in connection with the place of supply rules for B2C (business to consumer) telecommunications servicesFootnote94—which are taxable where the customer is established, has his permanent address or usually resides.Footnote95 For telecommunications services provided at a payphone kiosk for example, article 24a of the VAT Regulation provides the (rebuttable) presumption that the customer is established, has his permanent address or usually resides at the kiosk.Footnote96 The provider of the telecom services thus no longer needs to procure information on the actual place of residence of, let’s say, an otherwise unidentifiable French tourist who makes use of a payphone in a Berlin kiosk. In this manner, information asymmetries can be avoided. In a similar sense, (rebuttable) presumptions can be employed to facilitate the information position of the taxable person engaged in intra-Community trade in goods. For example, if the nature of the supplied goods supplied clearly lacks a consumptive purpose (e.g. the goods are industrial machine parts), that circumstance, if properly documented by the taxable person effecting the supply, may be employed as a presumption for the qualifying VAT status of the customer.Footnote97 In addition, in relation to chain transactions, the EU legislator may consider allowing party C to presume that the supply effected by party B does not imply an intra-Community acquisition for the former in case the latter has explicated, in writing, that any intra-Community transport has taken place in connection with the first supply.Footnote98

Even though it goes beyond the scope of this contribution to formulate a comprehensive set of remedies which may avert the materialisation of information asymmetries in practice, it would in my view be worthwhile to explore in what manner (rebuttable) presumptions and disclosure obligations can be employed to facilitate the information position of the taxable person.

4.2. The revised definite intra-Community VAT regime: a solution?

With a view to combating VAT fraud in intra-Community settings, the Commission has recently expressed its intentions to adopt an alternative destination-based intra-Community VAT regime that is to replace the current regime.Footnote99 The system, of which the general outlines have now been laid down in a proposal, provides that a taxable person charges the VAT of the Member State of destination of the goods to the customer (i.e. the ‘intra-Union supply’).Footnote100 Subsequently, the customer would be allowed deduct that VAT in the respective Member State, assuming he meets the standard requirements. Combined with a One-Stop Shop for the reporting and payment of VAT, the taxable person effecting the supplies would therefore potentially charge VAT in 28 Member States, arranging his VAT affairs however with only one tax administration.Footnote101 In addition, the proposals introduce the concept of Certified Taxable Persons (CTPs)—a special VAT status similar to the Authorized Economic Operator status in customs.Footnote102 Intra-Community supplies made to CTPs would be eligible for a VAT reverse charge mechanism, thus taking away VAT liability at the level of the supplier.Footnote103

At the moment of submission of this contribution, the Commission had only provided the general outlines of the envisaged new intra-Community VAT regime. Since the exact characteristics of the new regime are currently unknown, it is difficult to assess to what extent it will address the causes of information asymmetries in the context of intra-Community trade in goods.Footnote104 Further to this, it is possible that under the new regime the taxable person effecting the supply will still need to source information on the actual transport trajectory of the goods. The reason is that local supplies of goods receive a categorically different VAT treatment than intra-Union ones.Footnote105 In fact, with a view to his VAT liability, the taxable person will possibly not only have to assess whether his customer is a taxable person, yet also whether the latter has obtained the CTP status. Notwithstanding these potential aspects, I am of the opinion that the legislative steps towards a new intra-Community VAT regime create the opportunity for the EU VAT legislator to adopt provisions which facilitate the information position of taxable persons engaged in intra-Community trade. In that regard, it is perhaps possible to devise a regime which allows for an equal VAT treatment of all supplies within a supply chain. For example, if both party A and B can treat their supply as an intra-Union supply taxable in the Member State of destination, even if the goods are supplied twice and transported directly from the Member State of origin to the Member State of destination, the allocation of cross-border transport will no longer be the cause of information asymmetries between the various taxable persons within an intra-Community supply chain.Footnote106 When drafting its proposals, I truly hope that the Commission will indeed consider the information position of the taxable person in the broadest sense possible.

5. Conclusion

In this contribution, I addressed the phenomenon of information asymmetries in conjunction with the intra-Community EU VAT regime for B2B trade in goods. The materialisation of an information asymmetry within an intra-Community supply chain generally implies that one or more taxable persons are unable to comply with the legal VAT requirements applicable to them. Such asymmetries may ultimately lead to various adversities such as double taxation. Notwithstanding this, CJEU case law provides a certain extent of legal protection to taxable persons who are subject to an information asymmetry. Depending on the circumstances, an information asymmetry should not have legal implications (e.g. VAT assessments, fines) for a taxable person in a case that person has acted in good faith, and moreover has done everything which could reasonably be required from him to resolve the asymmetry or prevent its materialisation. Finally, (rebuttable) presumptions and disclosure obligations may be used to counter the materialisation of information asymmetries in practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 See articles 2(1)(b), 20 and 138(1) of the Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on the common system of value added tax, OJ L 347/1 (hereafter: VAT Directive), as well as Council Directive 91/680/EEC of 16 December 1991 supplementing the common system of value added tax and amending Directive 77/388/EEC with a view to the abolition of fiscal frontiers, OJ L 376/1.

2 Jiafang Wang, Zhiyong Feng and Chao Xu, ‘Proactive Communicating Process with Asymmetry in Multiagent Systems’ (2013) Journal of Applied Mathematics 1; Gavin Clarkson, Trond E Jacobsen and Archer L Batcheller ‘Information Asymmetry and Information Sharing’ (2007) 24 Government Information Quarterly 828.

3 Urs Birchler and Monika Bütler, Information Economics (Routledge 2007) 274; Gregory S Dawson, Richard T Watson and Marie-Claude Boudreau, ‘Information Asymmetry in Information Systems Consulting: Toward a Theory of Relationship Constraints’ (2010) 27 Journal of Management Information Systems 147.

4 E.g. Yin-Feng Gau and Zhen-Xing Wu, ‘Order Choices under Information Asymmetry in Foreign Exchange Markets’ (2014) 30 Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 106; David L Eckles and Martin Halek, ‘The Problem of Asymmetric Information: A Simulation of How Insurance Markets can be Inefficient’ (2007) 10 Risk Management and Insurance Review 93; Paul M Healy and Krishna G Palepu, ‘Information Asymmetry, Corporate Disclosure, and the Capital Markets: A Review of the Empirical Disclosure Literature’ (2001) 31 Journal of Accounting and Economics 405.

5 E.g. Anna Nagurney and Ladimer S Nagurney, ‘A Game Theory Model of Cybersecurity Investments with Information Asymmetry’ (2015) 16 Netnomics 127; Wang, Feng and Xu (n 2).

6 Exploiting his information advantage, the agent may choose to act in his own personal interest at the expense of the principal. For further reading on the principal-agent problem, refer to Maarten Mussche, Vertrouwen op informatie bij bestuurlijke taakvervulling (Wolters Kluwer Nederland 2011) 53; Michael C Jensen and William H Meckling, ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’ (1976) 3 Journal of Financial Economics 305. See also Martijn Ludwig, Frits Van Merode and Wim Groot, ‘Principal Agent Relationships and the Efficiency of Hospitals’ (2010) 11 The European Journal of Health Economics 291.

7 Lior J Strahilevitz, ‘Information Asymmetries and the Rights to Exclude’ (2006) 104 Michigan Law Review 1835. The author assesses whether information asymmetries as regards the character of trespassers influence the legal instruments that property owners rely on to protect their real estate properties.

8 Colin T Reardon, ‘Pleading in the Information Age’ (2010) 85 New York University Law Review 2170. The author studies the extent and implications of information asymmetries between plaintiffs and defendants in the course of legal proceedings.

9 Bradley C Karkkainen, ‘Bottlenecks and Baselines: Tackling Information Deficits in Environmental Regulation’ (2008) 86 Texas Law Review 1409. The author explores information asymmetries at the level of regulatory bodies in the context of environmental legislation and policymaking.

10 A search query on ‘information asymmetry’ in the database of EU law (EUR LEX) provides some results as regards statutory law (e.g. European Parliament and Council Directive 2011/24/EU of 9 March 2011 on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare, OJ L 88; European Parliament and Council Directive 2014/104/EU of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union, OJ L 349; Commission Implementing Regulation 2017/1993 of 6 November 2017 imposing a definitive anti-dumping duty on imports of certain open mesh fabrics of glass fibres originating in the People’s Republic of China as extended to imports of certain open mesh fabrics of glass fibres consigned from India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand, whether declared as originating in these countries or not, following an expiry review pursuant to Article 11(2) of the Regulation (EU) 2016/1036 of the European Parliament and of the Council, OJ L 288) yet these sources of law only employ the concept in the recitals without providing a definition.

11 European Parliament and Council Directive 2003/6/EC of 28 January 2003 on insider dealing and market manipulation (market abuse), OJ L 96.

12 Council Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 of 7 October 2010 on administrative cooperation and combating fraud in the field of value added tax, OJ L 268/1.

13 This definition relates specifically to the situations which this contribution aims to address, i.e. situations in which a taxable person is unable to comply with the legal requirements of VAT due to his inability to access information held by his transaction counterparties. Further, it reflects the primary tenets inherent to other definitions, such as interaction between multiple parties (cf. Wang, Feng and Xu (n 2), Clarkson, Jacobsen and Batcheller (n 2)) who are subject to relative information disparities (cf. Birchler and Bütler (n 3), Dawson, Watson and Boudreau (n 3)).

14 Article 213(1) of the VAT Directive provides that every taxable person is required to state when his activity as a taxable person commences, changes or ceases. Subsequently, the respective Member State shall take the measures necessary to ensure that these persons are identified by means of an individual number (i.e. VAT identification number), assuming they carry out taxable transactions for VAT purposes or are subject to the liability of VAT (cf. article 214(1) of the VAT Directive).

15 Case C-587/10, VSTR, EU:C:2012:592.

16 ibid.

17 Further to article 262 of the VAT Directive, a taxable person is required to report his intra-Community supplies of goods in a recapitulative statement, mentioning, amongst other information, the VAT identification number of his customers.

18 For certain transaction categories, article 226(4) of the VAT Directive demands that the taxable person includes the VAT identification number of his customer on the invoice.

19 Nonetheless, also in situations in which certain information is non-existent, a relevant question is to what extent the taxable person is and should be confronted with legal implications (e.g. VAT assessments, fines) in case he is unable to meet his VAT obligations. The CJEU has held on various occasions (Case, C-183/14, Salomie and Oltean, EU:C:2015:454, para 58; C-590/13, Idexx Laboratories Italia, EU:C:2014:2429, para 38) that the principle of fiscal neutrality requires that an exemption from VAT be allowed if the substantive requirements are satisfied, even if the taxable person has failed to comply with some of the formal requirements. Thus, as the Court rules in VSTR ((n 15), para 58), in a situation in which the supplier, who is acting in good faith and has taken all the measures which can reasonably be required of him, is unable to provide a VAT identification number but provides other information which is such as to demonstrate sufficiently that the person acquiring the goods is a taxable person acting as such, the tax authorities cannot deny the application of the exemption for intra-Community supplies (article 138(1) of the VAT Directive). This bestows a certain extent of legal protection on the taxable person who is confronted with non-existent information. Additionally, national law may contain grounds for absolving excuses; an example concerns force majeure, which can be invoked when external events (e.g. a natural disaster) of which the unforeseen and uncontrollable occurrence form the cause of non-compliance with fiscal requirements (cf. the Dutch Decree of 18 May 2000, nr. VB 2000/0850, relating to the Enschede fireworks explosions). De Bont is of the opinion that force majeure (Dutch: overmacht) in principle prevents the imposition of formal sanctions (reversal and intensification of the burden of proof) on the person subject to the administrative obligation, where that person has, in good faith and in the context of an agreement of safekeeping, outsourced the storage of his administration to a third party which subsequently refuses to relinquish that administration in spite of repeated requests. (Guido JME De Bont, commentary to the Dutch Supreme Court judgment of 27 January 2006, nr. 39 104, BNB 2006/191).

20 Article 138(1) of the VAT Directive, as well as VSTR (n 15).

21 In the context of intra-Community supplies, Amand notes that the taxable person may very well find it hard to procure sufficient documentary evidence that reflects the physical transport trajectory of the goods (e.g. in case parties have agreed on EXW Incoterms). Christian Amand, ‘The Impossible Proof of Intra-Community Supplies of Goods’ (2016) 27 International VAT Monitor 98.

22 The object of taxation relates to what is subjected to taxation. In EU VAT, the object of taxation is formed by the taxable transactions listed in article 2(1) of the VAT Directive (including the supply of goods and the supply of services).

23 Article 1(2) VAT Directive states that the principle of the EU VAT entails the application of a general tax on consumption. Scholars agree that EU VAT aspires to tax consumption (e.g. Alan Schenk, Victor Thuronyi and Wei Cui, Value Added Tax—A Comparative Approach (Cambridge University Press 2015) 1 and 11; Madeleine MWD Merkx, De woon- en vestigingsplaats in de btw (Wolters Kluwer Nederland 2010) 28; Rita De la Feria, The EU VAT System and the Internal Market (IBFD 2009) 52; Pernilla Rendahl, Cross-Border Consumption Taxation of Digital Supplies (IBFD 2009) 21).

24 Cf. article 56(2) of the VAT Directive.

25 I note that not only the information itself, but also its form is relevant for taxation purposes. This relates to the circumstance that the taxable person generally carries the burden of proof as regards his application of VAT (see, to this end, article 242 VAT Directive; Case C-285/09, R., EU:C:2010:742, para 46; C-268/83, Rompelman/Minister van Financiën, EU:C:1985:74, para 24). In order to satisfy the burden of proof, the taxable person generally requires the information to be reflected by ‘objective evidence’ which carries sufficient evidential value (e.g. contracts, invoices, customs documentation, and so on).

26 E.g. information which is available via the Chamber of Commerce, stock exchange publications, or the European Union’s online VIES-system (http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/vies/).

27 E.g. Case C-271/06, Netto Supermarkt, EU:C:2008:105; C-409/04, Teleos and others, EU:C:2007:548. A consumer purchasing a downloadable game on an online platform may for example falsely inform the platform that he resides in a Member State with a relatively low VAT rate, or a country with no consumption tax at all (e.g. by providing false address details, or by using a proxy server with an IP address located in such a country).

28 From CJEU case law, it follows that as a practical necessity, the system of VAT operates effectively. Cf. Case C-484/06, Koninklijke Ahold, EU:C:2008:394, para 39.

29 Article 37e of the Dutch VAT Act provides that a taxable person established in the Netherlands is deemed to supply his goods and services in the Netherlands, insofar as he does not prove the contrary with accounts and documentary evidence.

30 Whether or not Germany in fact claims taxing competences will likely depend on its awareness of the lease transaction.

31 The CJEU acknowledges the central function of sanctions (e.g. fines or other monetary implications for non-compliance), as they constitute measures ‘[…] the deterrent effect of which is intended to ensure compliance with [the respective] obligation’ (Case C-188/09, Profaktor Kulesza, Frankowski, Jóźwiak, Orłowski, EU:C:2010:454, para 28). Sanctions must however not constitute double taxation, and not go further than necessary to ensure the correct collection of VAT.

32 CJEU jurisprudence provides that, because of legal certainty and a practical application of VAT, parties should have regard (save in exceptional cases) to the objective character of the transaction concerned. E.g. Case C-354/03, C-355/03 and C-484/03, Optigen and others, EU:C:2006:16, para 45; C-439/04 and C-440/04, Kittel, EU:C:2006:446, para 41.

33 This concerns the neutrality principle. Cf. Case C-549/11, Orfey Balgaria, EU:C:2012:832, para 34; C-29/08, SKF, EU:C:2009:665 , para 67; C-109/02, Commission/Germany, [2003] EU:C:2003:586, para 20.

34 Ibid. The Commission currently defines a ‘destination-based VAT system’ as a system under which ‘goods traded across borders are taxed in the country where they are consumed’ (Commission Communication of 4 October 2017 on the follow-up to the Action Plan on VAT Towards a single EU VAT area—Time to act, COM(2017) 566 final, 7). Many scholars and institutions employ similar definitions (e.g. OECD, International VAT/GST Guidelines (OECD Publishing) 15; Marcin Gorazda and David E Benito, ‘Destination Principle in Intra-community Services and the “ Fixed Establishment” in the VAT, A Comparative Study of Polish and Spanish Law’ (2014) 42 Intertax 123; Andreas Normann and Oskar Henkow, ‘Logistics Principles vs. Legal Principles: Frictions and Challenges’ (2014) 44 International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 752; Puseletso Letete, ‘Between Tax Competition and Tax Harmonisation: Coordination of Value Added Taxes in SADC Member States’ (2012) 16 Law, Democracy & Development 132). However, during the years that the outlines of the EU VAT system were conceived, the destination principle (and, as its pendant, the origin principle) carried a different meaning based on the economic sciences. The authors of the Tinbergen report for example defined a destination-based VAT system as ‘a system […] which, by exemptions for exports and compensating duties on imports, would result in the products being liable to turnover tax only in the country of destination’ (Tinbergen Report, High Authority ECSC, March 5, 1953, 37). Initially, the principles thus related to the physical trajectory of goods across borders, rather than to the place where goods are ultimately consumed.

35 Articles 138(1) and 169(b) of the VAT Directive.

36 Articles 2(1)(b), 20, 40 and 200 of the VAT Directive.

37 Assuming all involved taxable persons are compliant, intra-Community transactions are reflected in the VAT return of the taxable person acquiring the goods (articles 250 and 251(c) of the VAT Directive), the VAT return of the taxable person supplying the goods (articles 250 and 251(a) of the VAT Directive), and the recapitulative statement of the supplier (arti0lce 262 of the VAT Directive).

38 R. (n 25), para 60.

39 See fn 17 f.

40 See also article 139(1) of the VAT Directive.

41 In particular, I note that article 139(1), second paragraph VAT Directive stipulates that the exemption of article 138(1) VAT Directive does not apply to the supply of goods to taxable persons or non-taxable legal persons, whose intra-Community acquisitions of goods are not subject to VAT pursuant to Article 3(1).

42 However, the actual risk of information asymmetries may be mitigated by the taxable amount; in case a taxable person makes supplies to a customer for an aggregate taxable amount exceeding the yearly threshold of article 3(2)(a) VAT Directive, he can safely assume that indeed the intra-Community acquisitions of this person are subject to VAT (and thus apply the intra-Community VAT regime). However, in that case, the taxable person carrying out the supply would still need to establish whether or not the customer is a non-taxable person not being a legal person, in which case the intra-Community VAT regime does not apply.

43 Article 139(1) of the VAT Directive provides that the exemption does not apply to the supply of goods to taxable persons, or non-taxable legal persons, whose intra-Community acquisitions of goods are not subject to VAT pursuant to Article 3(1). Further, the CJEU has held that it is for the supplier of the goods to furnish the proof that the conditions for the application of the exemption for intra-Community supplies are fulfilled (R. (n 25), para 60).

44 Alternately, if we assume that a) the supplier applies the exemption irrespective of the asymmetry, and b) the acquirer of the goods is not a person whose intra-Community acquisitions are subject to VAT, the former may be confronted with VAT assessments and other sanctions (e.g. fines) in either the Member State of origin or destination of the goods (depending on total turnover figures (cf. articles 32 to 34 of the VAT Directive)).

45 Even though the supplier does charge VAT, it could be that the acquirer of the goods is a person whose intra-Community acquisitions are subject to VAT. In that situation, the supplier charges VAT which the customer is not allowed to deduct—as it is unduly charged (cf. Case C-342/87, Genius Holding BV, EU:C:1989:635, para 15). Parties would then have to correct the unduly charged VAT. For further reading on this elaborate process, refer to Ad J Van Doesum, ‘A law of counteracting forces: the reimbursement of overcharged, unduly paid, overcollected and overpaid VAT’ (2013) EC Tax Review, vol. 3.

46 See n 33.

47 Unduly charged VAT is in principle not eligible for deduction (Genius Holding BV (n 45), para 15).

48 The VAT status of the customer can however still be the object of an information asymmetry in case the customer does not have a VAT identification number (i.e. when he failed to register for VAT purposes). This was the case in VSTR (n 15), in which the CJEU ruled that in certain situations, a Member State cannot refuse the exemption for intra-Community supplies on the sole ground that the supplier did not provide the VAT identification number of his customer. The EU legislator has recently proposed legislation which intends to ‘elevate’ the requirement of having a VAT identification number to a material condition for applying the exemption (cf. Commission Proposal of 4 October 2017 for a Council Directive amending Directive 2006/112/EC as regards harmonising and simplifying certain rules in the value added tax system and introducing the definitive system for the taxation of trade between Member States, COM(2017) 569 final).

49 Teleos and others (n 27). In its official publication of the terms, the International Chamber of Commerce states the following:

[…] ExWorks means that the seller delivers when it places the goods at the disposal of the buyer at the seller’s premises or at another named place (i.e. works, factory, warehouse, etc.) […] EXW represents the minimum obligation for the seller.

50 CMR notes are standardised dispatch notes drawn up on the basis of the Convention on the Contract for the International Carriage of Goods by Road, Geneva, 19 May 1956. In the context of EU VAT, they are generally employed as documentary evidence in support of the transport trajectory of goods. The Member States have varying standards for the substantiation of the intra-Community transport of goods. For example, Germany allows the substantiation of the cross-border transport on the basis of a document called Gelangensbestätigung (paragraph 6a Umsatzsteuergesetz/paragraph 17a Umsatzsteuerdurchführungsverordnung), whilst the Dutch tax authorities may require an extensive list of items of proof (including signed CMR bills of lading, packing notes, proof of payment, (copy) invoices, statements issued by the freight forwarder; see Dutch Supreme Court, 18 April 2003, nr. 37790, V-N 2003/22.10). The EU legislator has recently proposed legislation to harmonise the items of proof (cf. Commission Proposal of 4 October 2017 for a Council Implementing Regulation amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 282/2011 as regards certain exemptions for intra-Community transactions, COM(2017) 568 final).

51 ibid, para 60. The CJEU also referred to the principle of legitimate expectations; since the tax authorities themselves initially accepted the CMR notes as legitimate, it would be contrary to the principle of legal certainty (legitimate expectations) to subsequently allow them to deny the exemption to the taxable person (para 50).

52 ibid, para 58.

53 ibid, para 68. To enjoy this legal protection, the supplier must not have participated in VAT evasion and must have taken every reasonable measure in his power to ensure that the intra-Community supply he was effecting did not lead to his participation in such evasion.

54 An interesting aspect in my view is that the CJEU allows the taxable person to apply the exemption even though the objective characteristics of the transaction do not support this VAT treatment (since the goods may very well have not left the United Kingdom at all; a position taken by the UK tax authorities (cf. para 16)).

55 ibid, para 68.

56 The principle of proportionality, amongst other, demands that measures do not go further than necessary to achieve a legitimate purpose. E.g. Case C-259/12, Rodopi-M 91, EU:C:2013:414, para 38; C-110/98 to C-147/98, Gabalfrisa and others, C-110/98, para 52.

57 Case C-26/16, Santogal M-Comércio e Reparação de Automóveis, EU:C:2017:453. Amongst other, the Court rules that the supplier should not be confronted with VAT assessments in case he has, within the context of an intra-Community supply, acted in good faith and took reasonable steps within his power to avoid his participation in that fraud.

58 Joep JP Swinkels, ‘Carousel Fraud in the European Union’ (2008) 19 International VAT Monitor 110.

59 Cf. Frank JG Nellen, Information Asymmetries in EU VAT (Kluwer Law International 2017) 239; Martin Lambregts, ‘Over de oplettend Koopman, diens wetenschap en zorgvuldigheid’ (2013) Weekblad Fiscaal Recht 2013/1468;

60 Case C-101/16, Paper Consult, EU:C:2017:775, para 55.

61 Case C-80/11 and C-142/11, Mahagében and Dávid, EU:C:2012:373, para 54; C-499/10, Vlaamse Oliemaatschappij, EU:C:2011:871, para 25.

62 The Court has ruled that Community law cannot be relied upon for abusive or fraudulent ends (inter alia Case C-332/15, Astone, EU:C:2016:614, para 58; Kittel (n 32), para 54).

63 After the entry into effect of the intra-Community VAT regime in 1993, it soon became apparent that it was not free of weaknesses. Particularly, the regime proved to be susceptible to VAT fraud (as confirmed by the EU institutions themselves, e.g. Commission Communication (n 34), 3; Commission Proposal (n 48), 2; Commission Proposal of 21 December 2016 for a Council Directive amending Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of value added tax as regards the temporary application of a generalised reverse charge mechanism in relation to supplies of goods and services above a certain threshold, COM(2016) 811 final, 2; Commission Communication of 6 December 2011 on the future of VAT—Towards a simpler, more robust and efficient VAT system tailored to the single market, COM (2011) 851 final, 12; Commission Green Paper of 1 December 2010 on the future of VAT—Towards a simpler, more robust and efficient VAT system, COM(2010) 695 final, 5). Mala fide traders found out that they could purchase goods free of VAT from other Member States and supply them onwards to customers locally, only to disappear with the VAT proceeds (the so-called MTIC fraud; refer to Christophe Grandcolas, ‘Managing VAT in a borderless world of global trade: VAT trends in the European Union—lessons for the Asia-Pacific countries’ (2008) 62 Bulletin for International Taxation 136).

64 E.g. Case C-277/14, PPUH Stehcemp, EU:C:2015:719; R. (n 25); Case C-146/05, Collée, EU:C:2007:549; Kittel (n 32).

65 Despite various EU efforts to counter such VAT fraud—think of the quite recent adoption of the Quick Reaction Mechanism (see article 199b of the VAT Directive), which allows Member States to swiftly implement legislation that shifts the liability of VAT to the customer in case specific categories of goods or services are tainted by ‘sudden and massive fraud’—this weakness of the intra-Community VAT regime continues to persist. In fact, in its 2016 ‘Action plan on VAT’, the Commission estimates that cross-border fraud accounts for € 50 billion of revenue loss for the EU each year (Commission Communication of 7 April 2016 on an action plan on VAT—Towards a single EU VAT area—Time to decide, COM(2016) 148 final, 3).

66 Mahagében and Dávid (n 61), paras 41 and 60.

67 Following CJEU case law, the investigative responsibility of the taxable person forming part of an intra-Community supply chain extends beyond his immediate transaction counterparties (i.e. his direct supplier and customer). In Bonik for example, the CJEU provides that a Member State can deny rights (e.g. the right of deduction) to a taxable person in case that person

[ … ] knew or should have known that, through the acquisition of those goods or services, he was participating in a transaction connected with VAT fraud committed by the supplier or by another trader acting upstream or downstream in the chain of supply of those goods or services. (Case C-285/11, Bonik, EU:C:2012:774, para 40)

68 A similar situation is discussed by Ad J Van Doesum, Gert-Jan Van Norden and Herman WM Van Kesteren, Fundamentals of EU VAT Law (Kluwer Law International 2016) 490 (Figure 12.25).

69 Case C-245/04, EMAG Handel Eder, EU:C:2006:232.

70 Cf. Case C-84/09, X, C-84/09, para 33. For a detailed discussion of the allocation of intra-Community transport, refer to Frank JG Nellen/Govinda Kandhai, ‘De BTW-toerekening van intracommunautair vervoer bij ketentransacties’ (2017) Weekblad Fiscaal Recht 2017/214.

71 Case C-430/09, Euro Tyre Holding, EU:C:2010:786; C-386/16, Toridas, EU:C:2017:599.

72 Euro Tyre Holding (n 71), para 17; Toridas (n 71), para 17.

73 Toridas (n 71), para 37. In Euro Tyre Holding (n 71), para 33, the CJEU employs somewhat different wordings to the same end. It rules that the transport cannot be ascribed to the first supply in case the transfer of the power to dispose of the goods as owner for the second supply has taken place in the Member State of origin before the intra-Community transport has occurred.

74 In this context, see Redmar A Wolf, Nederlandse Documentatie Fiscaal Recht: commentaries on the Dutch VAT Act (Wet op de omzetbelasting 1968; Tabel II a.6 behorende bij Wet op de omzetbelasting 1968).

75 Toridas (n 71), para 21.

76 Euro Tyre Holding (n 71), paras 15 and 16.

77 ibid, paras 12 to 14 and 39.

78 ibid, para 37 .

79 ibid, paras 35 f. The CJEU adds that the supplier effecting the first supply might be held liable to VAT on that transaction if he had been informed by that person of the fact that the goods would be sold on to another taxable person before they left the Member State of supply and if, following that information, the supplier omitted to send the person acquiring the goods a rectified invoice including VAT.

80 Joep JP Swinkels, ‘Zero Rating Cross-Border Supplies of Goods under EU VAT—Triangular Takeaway Transactions’ (2012) 23 International VAT Monitor 403. If I understand Swinkels correctly, he argues that the material allocation of the intra-Community transport in fact depends on the provision of information by B. I see this somewhat differently. Assuming that party C has obtained ownership of the goods prior to the cross-border transport, and in case party B has declared that the goods would be transported to another Member State and has provided his VAT identification number as issued by that Member State, party A is allowed to treat his supply as an intra-Community supply (legal protection) even though from a material perspective that supply still qualifies as a local (taxed) supply in the Member State of origin.

81 Amand (n 21).

82 Aleksandra Bal, ‘Import and Export in Multi-Sale Transactions—Part II’ (2016) 27 International VAT Monitor 174.

83 ibid 170.

84 The principle of effectiveness requires that as a practical necessity, the system of VAT operates effectively. Cf. Koninklijke Ahold (n 28), para 39.

85 Often, parties within the supply chain are not eager to disclose information for fear of being excluded from the supply chain; their customers may ‘skip’ them and purchase from their suppliers instead.

86 In EU VAT law, the principle of proportionality demands that measures do not go beyond what is necessary to attain the objectives of ensuring the correct collection of tax. Rodopi-M 91 (n 56), para 38.

87 Euro Tyre Holding (n 71), para 38; Teleos and others (n 27), para 67.

88 On the basis of article 193 of the VAT Directive, VAT is payable by any taxable person carrying out a taxable supply of goods or services.

89 Teleos and others (n 27), para 66; see also, in the context of extra-EU trade, Netto Supermarkt (n 27), para 25.

90 An exception to this is formed by article 55 of the VAT Regulation, which demands that VAT entrepreneurs, when acting as customers to certain transactions, ‘communicate their VAT identification number forthwith to those supplying goods and services to them’.

91 Items of such evidence may for example be properly filled out CMR documents, bills of lading, customs documents, etc. For suggestions, refer to Commission Proposal (n 50), 8 f.

92 In this regard, I note that horizontal disclosure obligations should ideally be imposed only on taxable persons, as enforcement and compliance in case of non-taxable person (e.g. final consumers) would be complex affair.