ABSTRACT

The language-learning environments of children growing up bilingual are highly variable. For speech and language therapists (SLTs), understanding the features of these environments can enhance the quality of services. In New Zealand (NZ), the language learning environments for children in Arabic-speaking families are largely unresearched. Participants from 85 Arabic-speaking families living in NZ completed an online survey (with each participant representing one family). The survey collected information about some of the factors which are known to affect children’s bilingual language development. Analysis focused on education levels, parents’ language proficiencies, years in NZ, and language exposure. The Arabic-speaking population in this survey provided a high proficiency Arabic language-learning environment for their children. They had higher than average education levels and reported greater proficiency in Arabic than English. English proficiency in the parents was associated with education levels and length of time in NZ. Exposure to Arabic was predominantly within the home context. The consistent use of Arabic at home combined with a lack of formal teaching of Arabic literacy suggests that these children will be able to speak Arabic but may exhibit limited ability to read and write in Arabic. This information on a sample of Arabic families in NZ may be useful for service and educational planning purposes. SLTs are advised to investigate the individual linguistic environments of children growing up bilingual in Arabic and English in NZ as part of their practice.

Introduction

Speech language therapy services in English-dominant societies are working with increasingly diverse populations and challenged with the issues around how best to serve these populations (Morgan et al., Citation2016; Newbury, Bartoszewicz Poole, & Theys, Citation2020; Verdon, McLeod, & Wong, Citation2015). These demographic changes are driven by the increase in migrants from countries with different cultures and languages other than English. For services to meet the needs of these populations, professionals need to continuously increase their knowledge about these communities (Verdon et al., Citation2015). This is particularly true for therapists working with children who use two or more languages. Their language development is affected by the amount, type and quality of exposure children have in those languages (Leuner, Citation2008), and this can vary greatly between children.

A number of authors have concluded that speech and language therapists (SLTs) working with bilingual children are in danger of both over- and under-identifying speech, language and communication disorders in these children (Barragan, Castilla-Earls, Martinez-Nieto, Restrepo, & Gray, Citation2018; Morgan et al., Citation2016; Mulgrew, Duffy, & Kennedy, Citation2022; Wright Karem & & Washington, Citation2021). The differences between monolingual language learning, on which most of the material on children’s language development is based, and bilingual language learning means that the features of bilingual language development are less likely to be properly interpreted and this increases the risk of misdiagnosis of bilingual speakers. The use of standardized assessments using standard English scoring procedures for bilingual children has been found to result in an overdiagnosis of language disorders (Barragan et al., Citation2018; Wright Karem & & Washington, Citation2021). Therefore, SLTs need to apply culturally sensitive approaches in their interventions which distinguish linguistic and/or cultural differences from language and or/communication disorders (Wright Karem & & Washington, Citation2021). Yet, children from nondominant language and/or cultural groups are also less likely to be referred for speech and language therapy services and receive support services (Stow & Dodd, Citation2005; Morgan et al., Citation2016). This may interfere with early identification of problems, which is a key component of appropriate management. Both these factors mean that SLTs should expand their knowledge about diverse linguistic and cultural groups in their areas of practice (Mulgrew et al., Citation2022; Verdon et al., Citation2015). The delivery of educational and clinical services to bilingual children can be improved by planning how to support their bilingual language development (Kohnert, Citation2010), which has the potential to positively affect bilingual children’s sense of belonging in the society and help them build their identities (Bialystok, Citation2018).

In New Zealand (NZ), there is a need for a better understanding of the factors impacting on bilingual children’s language development. As indicated in Newbury et al. (Citation2020), the majority of SLTs who report having multilingual children in their caseloads feel that they do not have sufficient training and knowledge to work competently with this group. The current paper aims to help fill this gap by presenting data on the language-learning environments for a relatively under-researched population in NZ: children growing up in Arabic-speaking families.

The Arabic-speaking community in New Zealand

New Zealand (NZ) is considered a very diverse country with immigrants who speak more than 160 different languages (Statistics New Zealand [Stats NZ], Citation2018b). The Arabic language was ranked 20th among the top 25 languages spoken in NZ, spoken by 12,399 individuals at the time of the 2018 census (Stats NZ, Citation2018b). Arabic speakers were amongst the migrant groups that increased by more than 30% from 2006 to 2018. These groups include people from a range of Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American and African nations. While some of these groups began migrating to NZ decades ago, Arabic speakers are more recent immigrants (Stats NZ, Citation2018a).

There are three main groups of Arabic speakers who reside in NZ. The first group came originally as refugees because of the political instability in their countries (Tawalbeh, Citation2018). According to statistics from the NZ Parliament (Citation2008, Citation2020), Iraqis and Syrians form the largest part of this group. This group is small in comparison with the second group consisting of Arabic speakers who have come as skilled workers through the points system: a system enabling professionals to migrate to NZ (Stats NZ, Citation2018a). In the last 30 years, professionals from various Arabic-speaking countries have made NZ their permanent home (Stats NZ, Citation2018a). The final group of Arabic speakers have come as students. From 2015 to 2020 about 10,000 of these have come to NZ, with the majority from Saudi Arabia (Ministry of Education, Citation2022b).

The Arabic language

Arabic is the language of the Qur’an (the Islamic holy book), so it carries significance and value in religion as well as being the language of everyday life. It is spoken by more than 400 million people around the world and is the official/co-official language of 25 countries in the Arab League. Discussions of Arabic are complicated because of the presence of diglossia, or the coexistence of two distinct varieties of a language that are used in specific contexts: a standard variety used formally and for literacy purposes, and a spoken/dialectal Arabic used informally in daily speech. Modern standard Arabic and spoken Arabic can differ in syntax, semantics, morphology and phonology (Albirini, Citation2016). The spoken variety has many different dialects, which is expected, given the range of countries in the Arab world. Examples of the main dialects include Egyptian, Levantine (Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Palestine), Iraqi, Gulf (Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, U.A.E, some parts of Saudi Arabia, and Oman), Yemeni, and North African Arabic (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya). Each of these dialects also has subdialects, and the dialects are not all mutually intelligible. Egyptian and Levantine dialects are widely understood among Arabic speakers, but others such as North African dialects are not as widely understood and are influenced by other languages such as French (Miller, Al-Wer, Caubet, & Watson, Citation2008). Dialectical differences can be at the phonological, morphological, and lexical levels. For example, in most Arabic dialects the lexical representation for ‘car’ is the term /sæjɒːˈɾe/, but in the Egyptian dialect the word is /ʕa.ra.bij.ja/. An example of a phonological difference is ‘moon’; it is usually produced as /qamar/ in Yemeni Arabic, /ʔa.mar/ in Levantine Arabic and as /ɡʊmər/ in some varieties of Gulf Arabic. By contrast, modern standard Arabic is a uniform language used by all Arabic speakers (Miller et al., Citation2008), and is a simplified form of classical Arabic. Classical Arabic is the variety of Arabic in the Qur’an and is used primarily for Islamic practices such as prayers. Therefore, many non-Arab Muslims learn this form of Arabic to help them in Islamic practices.

Arabic as a minority language

There has been little research on the language-learning environments of children growing up with Arabic as a minority language. However, several studies suggest that in migrant communities adult Arabic-speakers retain the use of Arabic as their main language between each other (Al-Sahafi & Barkhuizen, Citation2006; Dagamseh, Citation2020), and that migrant Arabic-speaking families have a positive attitude toward maintaining the language and a desire to uphold their identity as Arabic speakers (Bahhari, Citation2020; Yazan & Ali, Citation2018). Bahhari (Citation2020) concluded that the main motivation for maintaining Arabic was to practise Islam and to keep the Islamic identity. Therefore, in addition to being able to speak Arabic, the ability to read classical Arabic is important (Al-Sahafi, Citation2015; Bahhari, Citation2020).

Studies have indicated that children are most likely to be exposed to Arabic as a minority language in three places; the home, schools that teach the Arabic language, and social events in the Arabic-speaking community (Al-Sahafi, Citation2015; Bahhari, Citation2020; Ferguson, Citation2013; Said & Zhu, Citation2017; Yazan & Ali, Citation2018). While there has been consistent agreement on home as the main source of exposure to Arabic (Al-Sahafi & Barkhuizen, Citation2006; Bahhari, Citation2020; Said & Zhu, Citation2017; Yazan & Ali, Citation2018), studies have also indicated that there is variation in how much Arabic and English are used at home. Some studies such as Al-Sahafi and Barkhuizen (Citation2006) and Bahhari (Citation2020) have reported extensive use of Arabic at home; other studies such as Said and Zhu (Citation2017) have reported extensive use of English. To understand such variation, it is important to consider the proficiency in both languages within families and the number of years spent in an English-speaking country. Obviously, not all children in minority language speaking families have equal opportunities to develop the minority language (Surrain, Citation2018).

Arabic language schools provide regular exposure to Arabic for children growing up in non-Arabic speaking countries. These schools operate on a part-time basis, and children attend them in addition to their regular schools. The focus is on practising the Arabic language and teaching Arabic literacy, and sometimes classical Arabic for religious practices (Bahhari, Citation2020; Ferguson, Citation2013; Said & Zhu, Citation2017). However, schools may not be particularly effective as language learning environments. Ferguson (Citation2013) found that the pattern of language use among teachers and students at a school can be asymmetric. Arabic was the dominant language among the teachers in the schools she observed, but English was the dominant language among the students. Furthermore, Ferguson (Citation2013) and Al-Sahafi (Citation2015) both pointed to the challenges that Arabic school attendees face in acquiring Arabic literacy skills, as the variety of Arabic taught there was generally modern standard Arabic, which was not the variety used in the home.

Some Arabic-speaking parents also send their children to Islamic schools (Bahhari, Citation2020). Islamic schools operate as full-time schools in non-Arabic speaking countries. In countries where the dominant language is English, children are taught the subjects in the curriculum in English. However, they are also exposed to classical Arabic because they take regular additional classes in Islamic studies. These classes introduce them to the reading of the Qur’an and other Islamic practices (Abdalla, Chown, & Memon, Citation2020). Currently there are three full-time Islamic schools operating in Auckland, NZ. They are recognized as state-integrated schools (Ministry of Education, Citation2022a) where the NZ curriculum is taught, in addition to classes in Islamic studies and Arabic language.

The existence of a concentration of speakers of a minority language presents an additional opportunity for language learning. Previous studies have highlighted that socializing with the wider Arabic-speaking community in different Western countries provided opportunities for children to hear and practise Arabic (Bahhari, Citation2020; Said & Zhu, Citation2017; Yazan & Ali, Citation2018). However, socializing with other Arabic speakers can vary between different families. Socializing can include visits to the extended family (Said & Zhu, Citation2017), video calls to extended family (Al-Sahafi, Citation2015), and playdates with other children from Arabic-speaking families (Yazan & Ali, Citation2018). Such details of Arabic language exposure may enhance the understanding of the presenting Arabic language competency of children growing up as Arabic-English bilinguals in NZ.

Factors affecting the language-learning environment

Previous research indicates there are several factors which can impact the language-learning contexts of children growing up with a home language different to the societal language (Curdt-Christiansen, Citation2009; Paradis & Jia, Citation2017; Paradis et al., Citation2022; Surrain, Citation2018). Factors which have been shown to be significant include family size, reasons for emigration from the home country, the length of stay in the host country, parental education and minority language proficiency (Hirsch & Lee, Citation2018; Montrul, Citation2013).

With regards to family size, Rojas et al. (Citation2016) found that the larger the family the more likely it is that older children already in the school system are bringing the majority language home, and this may lead to less use of the minority language More recently, Tsinivits and Unsworth (Citation2021) concluded that this may not necessarily be the case; they found that even if older siblings did bring the majority language home, this did not necessarily lower the use of the minority language by younger siblings. The influence of siblings and their language use is a factor to be considered, although the picture may be complex.

It is probable that the reasons leading people to move to another country affect language use (Hirsch & Lee, Citation2018), for example, refugees might represent a very different demographic and have different languages practices to those who choose to move voluntarily to another country (Paradis et al., Citation2022). Issues that impact refugee-population language practices, but not usually those of other migrants, include wellbeing difficulties such as posttraumatic stress, interrupted learning, and uncertainty about the length of their stay in the host country (Al Janaideh, Gottardo, Tibi, Paradis, & Chen, Citation2020; Paradis et al., Citation2022). The degree of commitment that a family might feel to a new country may influence their language practices (Fishman, Citation1991; Fillmore, Citation2000).

The number of years spent in the host country is a third factor. Longer residencies may lead to a greater proficiency in the majority language, and this may sometimes lead to a shift to the majority language. This is especially true if the children in those families were born in the host country (Fishman, Citation1991). Willard, Agache, Jäkel, Glück, and Leyendecker (Citation2015) found this to be the case as second generation immigrant parents used the majority language more than the first generation immigrant parents in their study. Children of the third generation may be exposed to less of the minority language at home, which is usually the main exposure site (Fishman, Citation1991).

A fourth factor is that of parental education. Research on this topic has produced mixed results. Karidakis and Arunachalam’s (Citation2016) analysis of data from the 2011 Australian census on languages spoken at home showed that as education level increased, individuals were more likely to adopt English as a home language. In their analysis immigrants with postsecondary qualifications were more likely to use English at home compared to immigrants with secondary school (or lower) levels of education. However, in Willard et al. (Citation2015) higher education in parents was positively associated with their children’s development of minority language, largely because they provided their children with opportunities to learn the minority language through literacy activities such as stories. It would seem that higher levels of parental education can impact home language learning differently in different minority language speaking groups (Winsler et al., Citation2014).

Finally, language proficiency of parents is also discussed as a factor in the literature. It has been suggested that children may become more proficiently bilingual if their parents speak the minority language with high proficiency (Sun, Low, & Chua, Citation2022). A reason may be that parents’ proficiency in the minority language impacts on their language use in social situations and the amount of minority language input children are exposed to (Tran, McLeod, Verdon, & Wang, Citation2021).

Aim of the study

It is important for SLTs working with bilingual children, to understand how various factors can impact bilingual language development. As the Arabic-speaking population grows in NZ; the possibility of therapists encountering children from this language background in their practice increases. More information is required about the language-learning environments of children growing up in Arabic-speaking families. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore these environments for children in Arabic speaking families by answering the following research questions: (1) What are the demographic characteristics of Arabic-speaking parents in NZ? (2) Where are these children exposed to Arabic language? (3) What associations are there between demographic characteristics, the settings children are learning Arabic in, and children’s Arabic language development?

Methods

This study used an online survey of Arabic-speaking families with children living in NZ. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC # 019687).

Recruitment

An invitation to participate in the survey, with links to a detailed information sheet and the survey itself, was distributed via social media postings, initially through the first author’s contacts in Arabic-language schools in Auckland. The language-school teachers then posted the invitation to a WhatsApp group for Arabic speakers in NZ. Snowball sampling was also used to recruit participants, following the recommendation of snowballing via social networks as a method of recruitment from minority groups (Parker, Scott, & Geddes, Citation2019). Potential participants were asked to pass on the recruitment notice or email it to anyone they knew who met the criteria. The study was also publicized through Facebook pages dedicated to Arabic-speaking and/or Muslim families in NZ, and Twitter accounts followed by specific relevant groups such as Saudi students in NZ.

The inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) families with children aged under 18 years old, with (2) parents speaking Arabic as their home language, and (3) families resident in NZ. The inclusion criteria were clearly stated at the beginning of the online survey. This gave potential participants an opportunity to decide if they met the criteria for the study before opening the anonymous online survey. In addition to that, survey results could be filtered to ensure that the participants met the inclusion criteria.

Included in the information at the beginning of the survey was a statement that submitting the survey would be considered as indicating consent to take part in the research. Around 200 people opened the survey link and read the questions, but not all participated as it was possible to view the survey without responding to the questions. This was not surprising as fear and hesitation about revealing personal information in surveys have been reported before for Arabic communities (Kadri, Citation2009). Of those who did participate 85 met the criteria.

Instrument

The survey was constructed using Qualtrics software. It was designed to be answered by a parent or the primary caregiver and included questions about both parents. The survey was developed in English and translated into Arabic by the first author, a native speaker of Arabic. This was then reviewed and edited by a second bilingual Arabic-English individual working in the field of English-Arabic translation whose first language was Arabic. All the information was available in both Arabic and English, and participants could choose a language option at the beginning.

The survey was designed to elicit information about the factors which can affect language development in bilingual children, where the first language of the parents is a minority language in the society they are living in. These include the reasons the family are in the country concerned (e.g., as refugees, voluntary migrants, students, etc.), the language proficiency including literacy in each language for the adults, the education level of the parents, and the amount of exposure the children have to each language (Curdt-Christiansen, Citation2009; Gollan, Starr, & Ferreira, Citation2015; Surrain, Citation2018; Willard et al., Citation2015; Winsler et al., Citation2014). The survey asked questions in each of these areas using different forms such as multiple-choice, Likert-style questions, and open-ended questions. For example, multiple choice answers were given for questions such as ‘What was your primary reason for moving to NZ?’:(1) Study, (2) Work, (3) Live permanently, (4) Refugee, (5) Other, please specify. Likert scales were used for questions such as ‘How good is your spoken Arabic language now?’: (1) Excellent (understand almost everything, very comfortable expressing myself in Arabic in all situations), (2) Very good (can understand and use Arabic adequately for work and most other situations), (3) Good (good understanding and can express myself on many topics), (4) Fair (some understanding and can say simple sentences), (5) Poor (no understanding or speaking ability). For open-ended questions about language exposure and spoken language such as ‘Where is/are your child/ren exposed to Arabic & English?’ or ‘What languages can you speak or understand?’, participants had the space to include as much information as they saw relevant. The survey was trialed with three people in the Arabic-speaking community, to ensure that the questions were clear and to identify any possible misunderstandings. Some minor modifications, mainly sentence rewording to clarify meaning, were made. Those who were included in the survey trial reported that they completed it in about 15 min.

Analysis

The quantitative data were analysed using a combination of descriptive and inferential statistics in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program Version 25, and the qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Descriptive statistics were used to obtain frequencies and percentages, and inferential statistics were used to find any associations between factors.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse open-ended questions about language exposure. Responses to these questions were coded inductively using semantic categories such as ‘school’, ‘day care’, ‘outside home’, ‘community events’, and ‘home’. The codes were reviewed, and the two main themes were identified as loci for children’s language exposure: the home and outside the home. Outside the home was further divided into formal and informal exposure. Formal exposure refers to continuous exposure to Arabic or English on a regular basis outside the home context through attending regular NZ schools, Arabic schools, and/or Islamic schools. Informal exposure refers to exposure to Arabic language outside the home through gatherings with Arabic speakers or attending Arabic-speaking community events, and to English through English-speaking contexts outside the home, e.g., public places like supermarkets etc. Based on this analysis, four patterns of language exposure were identified, and participants were divided into one of the four.

These four patterns of language exposure were analysed for any possible relationships with the categorical variables of parents’ proficiencies in Arabic & English, parents’ reasons for moving to NZ, their education levels, and the number of years in NZ using a chi-squared test. Significance was set at p = <.05. Data based on the numbers of years in NZ were presented as the ranges of less than 5 years, between 5 and 10 years, between 10 and 20 years, and more than 20 years.

Results

Countries of origin

The participants came from 14 different Arabic-speaking countries (). One participant came from Iran, which is not an Arabic-speaking country, as Farsi is the official language and the population mostly identifies as Persian rather than Arab, but there is an Arabic-speaking minority in Iran. Ten participants reported that their spouses came from different countries to themselves, with five of them from non-Arabic-speaking countries. This suggests they are not a homogeneous population and may be speaking a range of dialects.

Table 1. Participants’ home countries (n = 85).

Number of children

The results show that 88% of the participants had between one and three children in their households, and 77% of children had at least one sibling, but 12% had more than two. Three participants did not answer this question.

Language proficiency

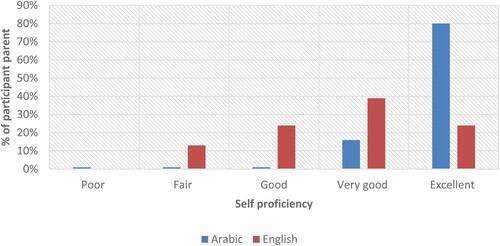

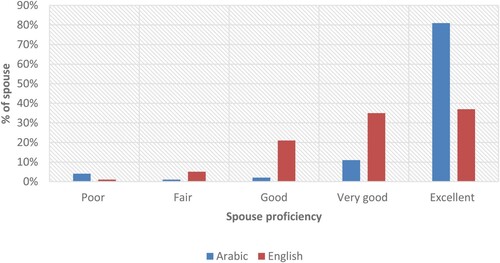

All of the participants rated their own language skills and those of their spouses in both Arabic and English and 82% rated both their own and their spouse’s Arabic fluency and literacy as ‘excellent’ (the top of the 5-point scale). Three participants reported English as a first language for them or their spouse, and another three spoke Kurdish, Farsi, and French as their first languages. Among those who reported Arabic as their first language, 68% of them reported that it was their stronger language, 22% reported that their Arabic and English were equally proficient, and 10% reported English was their stronger language. These participants were, by definition, bilingual in English and Arabic. However, most participants rated their and their spouse’s English oral language skills lower than their Arabic (see & ).

Moving to New Zealand

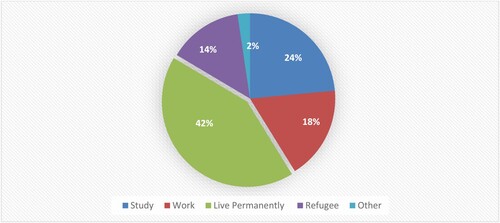

The participants in this study were largely in NZ by choice. Permanent residents represent 42%, 14% identified as refugees, and a further 42% were here for work or study (see ). This last group are most likely to be here temporarily, so this population may not be a stable one. Fifty six percent of the participants (permanent residents and refugees) are likely to be a permanent part of the NZ population.

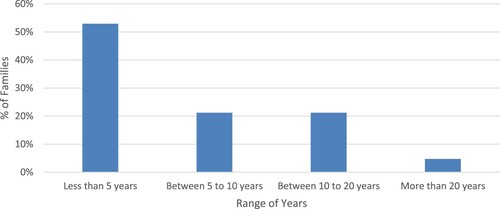

Over half of the sample had been in NZ for less than five years (see ). A chi-square test revealed a significant association between English proficiency and number of years in NZ, X2(9, N = 85) = 27.11, p = .001. The longer participants had been in NZ, the more likely they were to rate their English proficiency as higher.

Education and occupation

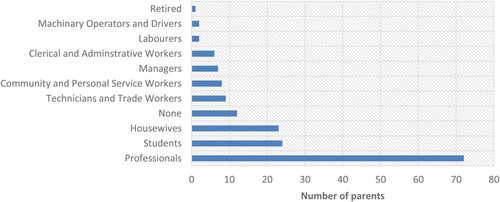

Education levels for the participants and their spouses were high: 53% had a bachelor’s degree, 32% a postgraduate degree, and 15% had no university qualification. Correspondingly a high proportion of participants and their spouses were in professional occupations, other skilled areas, or were students (). A chi-square test found a significant association between education level and rated proficiency in English, X2(9, N = 85) = 18.33, p = .031. The higher the education level, the higher the self-rating of proficiency in English.

Children’s language exposure

In this section participants were asked to provide information about their children’s exposure to Arabic and English; 59 participants responded to these questions. The participants’ answers are summarized and presented in . The results showed that all the respondents used Arabic at home and in informal settings outside the home, e.g., community events and events with other Arabic speakers. Under 30% of the respondents sent their children to more formal settings outside the home, e.g., language schools, for more exposure to Arabic. All participants indicated that their children were exposed to English outside the home in both formal and informal settings; 28% also used English with their children in the home. Under 10% of children were exposed to both languages in the home and in all settings outside the home.

Table 2. Children’s language exposure (n = 59).

Chi-square analyses were undertaken to determine any relationships between these patterns of language exposure and the number of years in NZ, parents’ Arabic and English language proficiency, and parents’ education. No significant relationship was found between children’s language-exposure pattern and the number of years spent in NZ, X2(9, N = 59) = 3.83, p = .922. Similarly, no significant associations were found between children’s language-exposure pattern and parents’ English proficiency, X2(9, N = 59) = 5.97, p = .743, children’s language-exposure pattern and parents’ Arabic proficiency,X2(3, N = 59) = 3.03, p = 0.386, or between children’s language exposure pattern and parents’ education, X2(9, N = 59) = 10.04, p = 0.347.

As the Arabic-language community school was one of the main formal sources of exposure to Arabic in this study, data were extracted from the 16 respondents who indicated their children attended such a school, to see if there was some commonality in the group (see ). The data showed that Arabic school attendees’ parents had relatively high educational levels, with at least one parent holding an undergraduate qualification. However, they were a diverse group in terms of the numbers of years the families had been in NZ. The range was from 1 to 25 years, with a mean of just under eight years, and 10 of the 16 had been in NZ for five years or more. The family who had been living in NZ for 25 years indicated that they sent their youngest child to Arabic-language community school for extra exposure to Arabic. The 16 participants also had varying reasons for moving to NZ. They came as permanent residents/migrants, refugees, and for work. The participants who came to study, the second largest group in the study, did not send their children to Arabic language schools.

Table 3. Arabic-language community school attendees (n = 16).

Discussion

This study investigated the language-learning environment of an under-researched linguistic population: Arabic-English-speaking children growing up in NZ. Of specific interest were the demographic characteristics of Arabic-speaking children’s parents and the associations between those, the settings for Arabic language learning, and children’s language development. Participants from 85 Arabic-speaking families living in NZ (each participant representing one family) completed an online survey.

The survey results showed that parents in these families reported a high proficiency in Arabic, generally higher than their English language skills. The participants had come to NZ from a variety of Arabic-speaking countries. Given that previous studies have found that parents’ proficiency in a minority language can enhance their children’s acquisition and use of that language (Sun et al., Citation2022; Tran et al., Citation2021) the parents’ strong proficiency in Arabic can potentially enhance the use of Arabic at home and provide a source of quality exposure for their children. The high level of Arabic language proficiency among these participants is related to the fact that the majority are first generation immigrants or recent arrivals to NZ. This would be a positive sign for Arabic language maintenance following Verdon, McLeod, and Winsler (Citation2014) where Arabic-speaking children were found to be more successful at maintaining their home language than children from other groups because they were more recent migrants to Australia. However, the impact of the high level of Arabic language proficiency might be somewhat diminished by family size. As indicated by Rojas et al. (Citation2016), where there is more than one child in a family, it is possible that older children already attending English language school may bring this language back into the home environment. The majority of this study’s participants had at least two children in their families, so there is certainly a risk of children shifting to English. It is difficult to know to what degree this factor can impact language shift as family size can also be viewed as increasing opportunities for family members to speak Arabic, particularly if parents encourage the use of Arabic with their children (Albirini, Citation2014; Gollan et al., Citation2015).

All the parents in this study were bilingual; most considered their Arabic proficiency to be excellent, but there was variation in their reporting of their English proficiency. The results show that the longer they have lived in NZ and the higher their education level, the more likely they are to have a higher level of English proficiency. This finding is in line with Blake, Mcleod, Verdon, and Fuller (Citation2018) who reported that multilingual Australians who speak English proficiently are more likely to have a higher education degree. However, this does not imply that greater proficiency in English or the number of years in NZ would result in a lack of exposure to Arabic at home. In this study, even families who had been living in NZ for more than 20 years, and who have described English as their strongest language, indicated they used Arabic at home, with some also sending their children to Arabic-language community schools. This might be expected when taking into consideration that the parents were not born in NZ and were first-generation arrivals. This finding for consistent Arabic language use at home among parents with a higher education contradicts Karidakis and Arunachalam (Citation2016), where a positive association between education and a shift to English use at home among minority language speakers is reported. However, it is in line with Leuner’s (Citation2008) suggestion that immigrants with higher education are aware of the significance of maintaining their minority language and make efforts to maintain it.

All participants used Arabic as their home language. Outside the home context, this study found that the main external sources of exposure to the Arabic language for children were through Arabic-language community schools, and/or Islamic schools. Previous studies indicated that children in Arabic-language community schools were exposed mainly to spoken Arabic by teachers, but were taught literacy in standard Arabic. The fact that teachers may speak a different variety of Arabic to that spoken by children’s families and the differences between spoken and written Arabic may affect children’s Arabic literacy levels, especially with longer texts (Al-Sahafi, Citation2015; Albirini, Citation2014; Ferguson, Citation2013). Ironically, English becomes the lingua franca in these schools as it is difficult to communicate across dialects, and standard Arabic becomes a specialist language focused on literacy (Al-Yaseen, Citation2021). In this study, only 27% of participants reported sending their children to Arabic-language community schools or Islamic schools. This suggests that there are potentially a large number of children in Arabic-speaking families in NZ who speak Arabic but cannot read or write it. Bilingualism in Arabic and English among those children therefore may not imply biliteracy. This is in line with Dagamseh’s (Citation2020) finding of limited Arabic literacy skills among Arabic speakers who moved to NZ as children or were born in NZ. This is the result of the primary source of exposure to Arabic being within the home and the lack of official organizational support for Arabic in NZ (Al-Sahafi, Citation2015).

Clinical implications

The findings in this study are important for SLTs to take into consideration when working with bilingual Arabic-English-speaking children. Verdon et al. (Citation2015) emphasized the importance of culturally competent practice and highlighted the need for SLTs to increase their knowledge of languages and cultures, and to consider cultural and social contexts when working with families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. This study provides some background for Arabic-speaking families in NZ, by shedding some light on the linguistic environment for children growing up speaking Arabic.

The results of this study show that SLTs working with Arabic speaking children should collect information about children’s exposure to the two languages, both at home and outside of home. The dialect of spoken Arabic should be ascertained, and whether there is more than one dialect spoken in that family. Parent and children’s proficiencies around spoken and standard Arabic should be discussed, along with biliteracy issues for both languages. The SLT should find out if the children have any opportunities to use Arabic. This includes information as to whether the children attend Arabic language schools and have connections with the Arabic-speaking community. In addition to that, SLTs need to know about parents’ proficiency in English, their education level, and the number of years since they moved to NZ or another English-speaking country. Collecting such information can enhance the understanding of children’s bilingual development.

This study results highlight that not all Arabic-speaking parents in NZ can speak English fluently. This is especially true if they are new to living in an English-speaking country or do not have high levels of education, as these two factors may limit parents’ exposure to English. If speech and language therapy is needed, parents’ limited English proficiency might affect the validity of a home programme and generalization of therapy goals that are in English. Therefore, SLTs need to provide a clear demonstration and explanation to the parents and, if possible, provide training to parents when needed. When working with Arabic-speaking interpreters, SLTs should ensure that both the client and the interpreter can understand each other as not all Arabic dialects are mutually understood by Arabic speakers (Khamis-Dakwar & Khattab, Citation2014). Guiberson (Citation2020) has called for SLTs to use innovative ideas when providing intervention for bilingual children. Such innovative ideas may include utilizing digital dual language books (Cuervo & Hobek, Citation2021), or encouraging translanguaging between the child’s languages (García & Otheguy, Citation2017).

Study limitations

This survey had relatively limited numbers (85 participants) and it is not entirely clear whether these 85 were representative of the Arabic-speaking population in NZ. The high proportion of students and NZ’s migration policy that favors migrants with skills that contribute to the nation’s economic growth may mean that the unusually high education levels are, in fact, representative, but we cannot be sure. Participant recruitment in Arabic-speaking communities is most successful through personal relationships and word of mouth (Khamis-Dakwar & Khattab, Citation2014), but this may also bias the sample. However, due to the limited amount of information about the Arabic-speaking population in NZ, the survey sample could not be compared with previous data to be sure. The New Zealand censuses do not include a specific and precise information about the Arabs as information about Arabs up to and including 2018, were collected under the umbrella category Middle Eastern, Latin American or African.

The survey asked about a limited number of factors, and the emphasis was on the learning of Arabic as a minority language in NZ. No measures were taken of proficiency, and self-ratings of proficiency may be subject to error. Parallel questions about children’s exposure to English were not asked, nor were any measures made of either of the children’s languages. This is not possible in a survey, however future studies could add to the knowledge base by measuring proficiencies in both children and parents.

Conclusion

Overall, this study revealed a high and consistent use of Arabic amongst these Arabic-speaking families in NZ. A high proficiency in Arabic was reported among parents with Arabic as their strongest language. Parental English proficiency was associated with how long they have been living in NZ and their education levels. In this study, the children’s main source of exposure to Arabic language was the home. External support for Arabic language was limited to Arabic-language community schools and gatherings with other Arabic-speaking families. However, the school setting was the main source of exposure to English.

While this study provides an overview of some of the basic factors related to the language-learning environment in Arabic-speaking families in NZ, more studies are needed. It would be useful to obtain naturalistic data for studies of bilingual Arabic-English-speaking children’s proficiencies in both languages. Studies could focus on different aspects of speech and language development, e.g., lexical, phonological, and morpho-syntactic, as this information may yield further insights into bilingual language development and provide benchmarks for SLTs assessing Arabic-English-speaking children. Another perspective would be to explore attitudes and understandings of communication difficulties in Arabic-speaking families. These types of studies would provide valuable insights into how SLTs can support children’s bilingual language development and tailor services to their needs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdalla, M., Chown, D., & Memon, N. (2020). Islamic studies in Australian Islamic schools: Learner voice. Religions, 11(8), 1–15. doi:10.3390/rel11080404

- Albirini, A. (2014). Toward understanding the variability in the language proficiencies of Arabic heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism, 18(6), 730–765. doi:10.1177/1367006912472404

- Albirini, A. (2016). Modern Arabic sociolinguistics: Diglossia, variation, codeswitching, attitudes and identity. London: Routledge.

- Al Janaideh, R., Gottardo, A., Tibi, S., Paradis, J., & Chen, X. (2020). The role of word reading and oral language skills in reading comprehension in Syrian refugee children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 41(6), 1283–1304. doi:10.1017/S0142716420000284

- Al-Sahafi, M. (2015). The role of Arab fathers in heritage language maintenance in NZ. International Journal of English Linguistics, 5(1), 73–83. doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n1p73

- Al-Sahafi, M. A., & Barkhuizen, G. (2006). Language use in an immigrant context: The case of Arabic in Auckland. NZ Studies in Applied Linguistics, 12(1), 51–69.

- Al-Yaseen, W. S. (2021). Teaching English to young children as an innovative practice: Kuwaiti public kindergarten teachers’ beliefs. Cogent Education, 8, 1. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2021.1930492

- Bahhari, A. (2020). Arabic language maintenance amongst sojourning families in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 13, 1. doi:10.1080/01434632.2020.1829631

- Barragan, B., Castilla-Earls, A., Martinez-Nieto, L., Restrepo, M. A., & Gray, S. (2018). Performance of low-income dual language learners attending English-only schools on the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition, Spanish. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(2), 292–305. doi:10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0013

- Bialystok, E. (2018). Bilingual education for young children: Review of the effects and consequences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(6), 666–679. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1203859

- Blake, H. L., Mcleod, S., Verdon, S., & Fuller, G. (2018). The relationship between spoken English proficiency and participation in higher education, employment and income from two Australian censuses. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(2), 202–215. doi:10.1080/17549507.2016.1229031

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. doi:10.1037/qup0000196

- Cuervo, S., & Hobek, A. (2021). Tutorial: Digital bilingual books for dual language learners eHearsay. Electronic Journal of the Ohio Speech-Language Hearing Association, 11(1), 42–50. Retrieved from https://www.ohioslha.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/WinterIssue2021.pdf

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2009). Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy, 8(4), 351–357. doi:10.1007/s10993-009-9146-7

- Dagamseh, M. (2020). Language maintenance, shift and variation evidence from Jordanian and Palestinian immigrants in Christchurch NZ (Unpublished PhD dissertation). University of Canterbury. Retrieved from https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/100139

- Ferguson, G. R. (2013). Language practices and language management in a UK Yemeni community. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(2), 121–135. doi:10.1080/01434632.2012.724071

- Fillmore, L. W. (2000). Loss of family languages: Should educators be concerned? Theory into Practice, 39(4), 203–210. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip3904_3

- Fishman, J. (1991). Reversing language shift: Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- García, O., & Otheguy, R. (2017). Interrogating the language gap of young bilingual and bidialectal students. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(1), 52–65. doi:10.1080/19313152.2016.1258190

- Gollan, T. H., Starr, J., & Ferreira, V. S. (2015). More than use it or lose it: The number-of-speakers effect on heritage language proficiency. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(1), 147–155. doi:10.3758/s13423-014-0649-7

- Guiberson, M. (2020). Introduction to the forum: Innovations in clinical practice for dual language learners, Part 2. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1113–1115. doi:10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00153

- Hirsch, T., & Lee, J. S. (2018). Understanding the complexities of transnational family language policy. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(10), 882–894. doi:10.1080/01434632.2018.1454454

- Kadri, J. (2009). Resettling the unsettled: The refugee journey of Arab Muslims to NZ (Unpublished PhD dissertation). Auckland University of Technology. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10292/988

- Karidakis, M., & Arunachalam, D. (2016). Shift in the use of migrant community languages in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1023808

- Khamis-Dakwar, R., & Khattab, G. (2014). Cultural and linguistic considerations in language assessment and intervention for Levantine Arabic speaking children. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 21(3), 78. doi:10.1044/cds21.3.78

- Kohnert, K. (2010). Bilingual children with primary language impairment: Issues, evidence and implications for clinical actions. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43(6), 456–473. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.02.002

- Leuner, B. (2008). Migration, multiculturalism and language maintenance in Australia: Polish migration to Melbourne in the 1980s. Lausanne: Peter Lang.

- Miller, C., Al-Wer, E., Caubet, D., & Watson, J. C. E. (2008). Arabic in the city: Issues in dialect contact and language variation. New York: Routledge.

- Ministry of Education. (2022a). Different types of primary and intermediate schools. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://parents.education.govt.nz/primary-school/schooling-in-nz/different-types-of-primary-and-intermediate-schools/

- Ministry of Education. (2022b). International students in NZ. Education Counts. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/international-students-in-new-zealand

- Montrul, S. (2013). Bilingualism and the heritage language speaker. In W. Ritchie & T. Bhatia (Eds.), The handbook of bilingualism (pp. 174–189). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Morgan, P. L., Hammer, C. S., Farkas, G., Hillemeier, M. M., Maczuga, S., Cook, M., & Morano, S. (2016). Who receives speech/language services by 5 years of age in the United States? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(2), 183–199. doi:10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0201

- Mulgrew, L., Duffy, O., & Kennedy, L. (2022). The assessment of minority language skills in English–Irish-speaking bilingual children: A survey of SLT perspectives and current practices. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57(1), 63–77. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12674

- Newbury, J., Bartoszewicz Poole, A., & Theys, C. (2020). Current practices of NZ speech-language pathologists working with multilingual children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22(5), 571–582. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1712476

- New Zealand Parliament. (2008). Immigration chronology: Selected events 1840–2008. Retrieved October 20, 2022, from https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/research-papers/document/00PLSocRP08011/immigration-chronology-selected-events-1840-2008

- New Zealand Parliament. (2020). The NZ refugee quota: A snapshot of recent trends. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/library-research-papers/research-papers/the-new-zealand-refugee-quota-a-snapshot-of-recent-trends/

- Paradis, J., & Jia, R. (2017). Bilingual children's long-term outcomes in English as a second language: Language environment factors shape individual differences in catching up with monolinguals. Developmental Science, 20(1), Article e12433. doi:10.1111/desc.12433

- Paradis, J., Soto-Corominas, A., Vitoroulis, I., Al Janaideh, R., Chen, X., Gottardo, A., & Georgiades, K. (2022). The role of socioemotional wellbeing difficulties and adversity in the L2 acquisition of first-generation refugee children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 25(5), 921–933. doi:10.1017/S136672892200030X

- Parker, C., Scott, S., & Geddes, A. (2019). Snowball sampling. In P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug & R. A. Williams (Eds.), SAGE research methods foundations. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rojas, R., Iglesias, A., Bunta, F., Goldstein, B., Goldenberg, C., & Reese, L. (2016). Interlocutor differential effects on the expressive language skills of Spanish-speaking English learners. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(2), 166–177. doi:10.3109/17549507.2015.1081290

- Said, F., & Zhu, H. (2017). “No, no Maama! Say ‘Shaatir ya Ouledee Shaatir’!” Children’s agency in language use and socialisation. International Journal of Bilingualism, 23(3), 771–785. doi:10.1177/1367006916684919

- Statistics NZ. (2018a). Arab ethnic group. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-ethnic-group-summaries/arab

- Statistics NZ. (2018b). NZ’s population reflects growing diversity. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-zealands-population-reflects-growing-diversity

- Stow, C., & Dodd, B. (2005). A survey of bilingual children referred for investigation of communication disorders: A comparison with monolingual children referred in one area in England. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders, 3(1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/14769670400009959

- Sun, H., Low, J., & Chua, I. (2022). Maternal heritage language proficiency and child bilingual heritage language learning. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13670050.2022.2130153

- Surrain, S. (2018). ‘Spanish at home, English at school’: How perceptions of bilingualism shape family language policies among Spanish-speaking parents of preschoolers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(8), 1163–1177. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1546666

- Tawalbeh, A. (2018). Transition as a focus within language maintenance research: Wellington Iraqi refugees as an example. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2018(251), 179–202. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2018-0011

- Tran, V. H., McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & Wang, C. (2021). Vietnamese-Australian parents: Factors associated with language use and attitudes towards home language maintenance. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, doi:10.1080/01434632.2021.1904963

- Tsinivits, D., & Unsworth, S. (2021). The impact of older siblings on the language environment and language development of bilingual toddlers. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(2), 325–344. doi:10.1017/S0142716420000570

- Verdon, S., McLeod, S., & Winsler, A. (2014). Language diversity, use, maintenance, and loss in a population study of young Australian children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(2), 168–181. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.12.003

- Verdon, S., McLeod, S., & Wong, S. (2015). Supporting culturally and linguistically diverse children with speech, language and communication needs: Overarching principles, individual approaches. Journal of Communication Disorders, 58, 74–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.10.002

- Willard, J., Agache, A., Jäkel, J., Glück, C., & Leyendecker, B. (2015). Family factors predicting vocabulary in Turkish as a heritage language. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(4), 875–898. doi:10.1017/S0142716413000544

- Winsler, A., Burchinal, M. R., Tien, H., Peisner-Feinberg, E., Espinosa, L., Castro, D. C., … Feyter, J. D. (2014). Early development among dual language learners: The roles of language use at home, maternal immigration, country of origin, and socio-demographic variables. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 750–764. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.02.008

- Wright Karem, R., & & Washington, K. N. (2021). The cultural and diagnostic appropriateness of standardized assessments for dual language learners: A focus on Jamaican preschoolers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(3), 807–826. doi:10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00106

- Yazan, B., & Ali, I. (2018). Family language policies in a Libyan immigrant family in the U.S.: Language and religious identity. Heritage Language Journal, 15(3), 369–387. doi:10.46538/hlj.15.3.5