Abstract

This article presents an interpretation of nostalgia in which it is traced back to its original meaning as an emotion concerned not with time, but with place, the Alpine mountains of Switzerland, which in the early nineteenth century became associated with notions of the medieval past. With recourse to nineteenth-century anthropological theories of cultural evolution, an attempt is made to explain the term’s shift in meaning. Nostalgia, as an emotion glorifying authenticity, was and still is propelled by imagery created in a wide variety of media. It found early and long-lasting expression in the international popularity of the Swiss chalet.

Introduction

The meaning of nostalgia has changed radically over the centuries, from a serious medical condition to a bitter-sweet yearning for a period of the past.1 The term originally referred to a condition of melancholia best described as severe homesickness.2 First labeled as such in a late seventeenth-century medical treatise, nostalgia was more commonly known as the “Swiss illness” (Schweizer Krankheit), because Swiss mercenaries serving abroad, most notably former mountain herdsmen, often suffered from it.3 Nostalgia was seen as a disease of the soul that mainly affected simple people who were raised in the mountains and had lived close to Nature.4 Returning home, or at least the prospect of a speedy return, was the only cure for seriously afflicted patients.

A century later, a longing for the mountains, and for Alpine Switzerland in particular, took hold of the eighteenth-century European elite, who had never set foot on a mountain trail. A new, aristocratic version of the Swiss illness manifested itself through the erection of Swiss chalets as garden follies on landed estates. A fascination with the Alpine mountains as Europe’s most exotic and primitive region was shared by intellectuals, for whom it was part of a search for the origin of western civilization (). The nineteenth-century intellectual obsession with civilization’s founding time and places of origin raised a deep interest in the Swiss chalet as Europe’s “primitive hut,” and initiated a drive to explore the isolated mountainous interior of Switzerland.5 This article proposes that the elitist Swiss illness as a longing for unfamiliar far-away places, or Fernweh as it is called in German, should be discussed in relation to the homesickness or Heimweh of the Swiss mercenaries in their longing for a familiar place.6

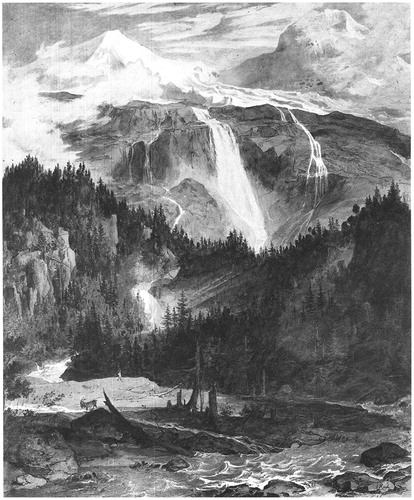

Figure 1 The Alpine mountains through the eyes of the nineteenth-century artist Josef Anton Koch. “The waterfall at Schmadribach,” nineteenth century, watercolor. Reproduced with permission of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Well into the twentieth century, Switzerland and the Swiss chalet united nostalgic longings for both the familiar and the unfamiliar. It was only in the 1960s that a predominantly time-bound interpretation of nostalgia eclipsed the original place-bound meaning of the term.7 Even then, the veneration of the flower-power generation for the relics of the domestic past (old sewing machines and baskets, tables, chests and chairs, etc.) was blended with a place-bounded nostalgia, demonstrated in a craving for ever more exotic far-away places such as India and Afghanistan.8 These ludic expressions of nostalgia were fiercely criticized as signs of societal malaise, of escapism indicative of an ill-feeling for the present – the flower-power generation was also the generation of the protest movement.9 In the 1980s, nostalgia was again seen as antagonistic, when architects labeled as post-modern incorporated historical (and also regional) references into their work, with playful but critical intent.10

The passion for the Swiss chalet seems to have been induced by an eighteenth-century work of fiction, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s epistolary novel Julie, ou la Nouvelle Héloïse (first published in 1761). The theme of both the chalet and the Swiss illness, whether of the first or second degree, is present in popular works of art throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from novels to operas and films – Johanna Spyri’s children’s book Heidi (1880), first made into a film in 1937, is merely the most famous example. In architecture, the chalet as both type and style enjoyed long-lasting and international popularity, ranging eventually from Norway to Portugal, from North America to India. An example of the potency of imagery created in fiction, the love for the chalet is a remarkable history of the intimate relation between architecture and cultural ideology.11

This article puts forward a cultural anthropological interpretation of nostalgia. It returns to the term’s original seventeenth-century meaning as an emotion related to a place, the Alpine mountains of Switzerland, and looks at how they were first exoticized before, in the early nineteenth century, becoming tied up with notions of the medieval past. With recourse to nineteenth-century anthropological theories of cultural evolution and cultural diffusion, an attempt is made to explain why the original place-related dimension of nostalgia was turned into a temporal dimension through the course of the nineteenth century, an apparent looking backwards which became the main focus of criticism of nostalgia in the twentieth century.12

The Swiss Illness

The Helvetian tribe was well known for its savagery and fierceness. However, by the fifteenth century, poor living conditions in Europe’s mountainous interior had driven many of its warriors into the service of foreign warlords. As mercenary soldiers, Swiss herdsmen were the early modern migrant laborers who provided the backbone, both dreaded and respected, of many of Europe’s royal armies. Their status as fearless fighters, though, was complicated by their reputation also as soldiers frequently tormented by a homesickness so severe it could be fatal.13 The Swiss illness became legendary. Stories circulated about the effect on Swiss mercenaries of a particular tune, called Kühreihen in German or Ranz des Vaches in French, which was sung by herdsmen on the festive occasions of bringing the cattle to the upper pastures in the spring and back in the fall.14 A reminder of key moments in the annual lifecycle of their pastoral communities, it was guaranteed to induce homesickness if heard.

In 1688, when Swiss medical student Johannes Hofer was only nineteen, he graduated from the University of Basel with a dissertation on the topic of homesickness.15 Written in Latin, its title was in both Greek and German: Nostalgia oder Heimwehe. Hofer’s first aim was to invent a proper medical name for this disease which, although commonly recognized, had not previously been a specific object of study. He had difficulty deciding between nostalgia (a contraction of the Greek nosos, return to the native land, and algos, suffering or grief) and philopatriedomania (love of the fatherland); in a reprint of his thesis of 1710 he switched to yet another term, pothopatridalgia (the pain of longing for the fatherland), before returning to nostalgia in a third edition of 1745. Despite this terminological indecision, he was straightforward in describing the symptoms of “an afflicted imagination” and its detrimental and potentially fatal effects on the body.16 The two case histories he studied described miraculous recoveries from the disease when the Swiss patients returned home.

The question of why the Helvetians in particular were susceptible to nostalgia remains largely unresolved. Hofer defined the disease as a fear of unknown environments and an inability to adapt to an unfamiliar way of life (centuries later, anthropologists would describe a similar psychological response to new conditions as culture shock). According to Hofer, it was most prevalent among youngsters coming from isolated communities who were not used to communicating with strangers. Swiss mercenaries fitted all these categories. In the 1710 edition of Hofer’s treatise, the musical notes of the Kühreihen tune were printed at the end, thus strengthening the link between nostalgia and the Alpine Swiss.17

The legend of the impact of the song on Swiss mercenaries was gradually exaggerated. In 1764, nearly a century after Hofer’s treatise first appeared, Rousseau claimed in his Dictionnaire de Musique (1764) that to prevent desertion Swiss mercenaries were forbidden to sing the Ranz-des-Vaches and risked the death penalty if they did. Rousseau attributed the impact of the song not to its musical quality, but to its memory-invoking ability, in particular its ability to trigger grief amongst those who had almost forgotten their former, simpler mountain lives.18 In his stress on loss and regret instead of longing and return, Rousseau seems to have anticipated the time-bound interpretation of nostalgia which would become prevalent in the nineteenth century.

But it was another of Rousseau’s works that was responsible for engendering the second version of the Swiss illness. Fernweh, the passion for Switzerland’s exotic mountains, and for the Swiss chalet in particular, was the opposite of the fear of strange environments characteristic of the Heimweh of the Swiss mercenaries. The full title of Rousseau’s influential romantic novel reads, in English, Julie, or the New Heloise: Letters of Two Lovers Living in a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps. Published three years before his Dictionnaire de Musique, it was an immediate international success.19 The Rhaeto-Romanic word chalet, formerly used only rarely outside Switzerland, suddenly became commonplace, in both French and English.20 The novel makes no reference to the legendary song of the Ranz-des-Vaches, but it does celebrate and exoticize the simple life of Swiss peasants within their Alpine surroundings.

In his title, Rousseau alludes to the famous medieval correspondence between Heloïse and her tutor, the monk Peter Abelard, father of her child. Julie is also a collection of letters, this time fictional, mainly between Julie, a girl of high birth, and her tutor of lower descent. She is passionately in love with him, but forbidden to marry. As a result, she suggests to him a secret rendezvous. “Leave [it] to your Julie,” she writes, seductively, “did you ever regret having been obedient to her voice?” Her directions to what will be their secret lovers’ nest are descriptively clear:

Near the flowery hillsides from which flow the sources of the Vevaise, there is a solitary hamlet that sometimes serves as a shelter for hunters and should only serve as a sanctuary for lovers. Round about the principal habitation […] are scattered at some distance a few Chalets, which with their thatched roofs can cover love and pleasure, friends of rustic simplicity. The hale and discreet dairymaids know how to keep for others the secret they need for themselves. The streams that cross the meadows are lined with delightful shrubs and trees. Dense woods further on offer wilder and darker retreats.21

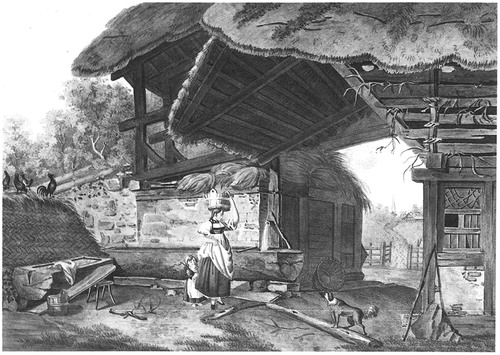

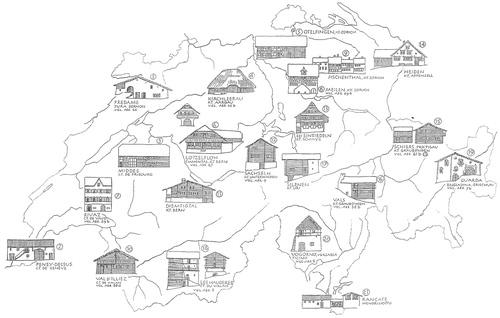

Of the specific characteristics of the novel’s Swiss chalet and its setting (indicated in italics), the thatched roof is the most distinctive. This roofing type was common in the eighteenth century in the middle regions of Switzerland, roughly from Lake Geneva north and eastwards to Lake Constance (Julie is set largely in the area around Vevey, a small town on Lake Geneva’s northern shore) ().22 The description of the chalet’s immediate environment indicates a location some way below the tree line, in the lower mountain regions. It is another short passage, in which Julie’s lover gives a passionate account of his guided tour through the high mountains north of Vevey, that seems to have given rise to the longing for the Alpine landscape so characteristic of the Swiss illness of the second degree. Julie’s tutor is enthralled by the serene, pure air and

Figure 2 Thatch was the dominant characteristic of the chalet first described by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and a common roofing in the middle regions of Switzerland until the end of the nineteenth century. Franz Niklaus König, “Peasant House in the Canton of Bern,” nineteenth century, watercolor. Reproduced with permission of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

the beauty of a thousand stunning vistas; the pleasure of seeing all around one nothing but entirely new objects, strange birds, bizarre and unknown plants, of observing in a way an altogether different nature, and finding oneself in a new world.23

He also praises the hospitality of the mountain-dwellers who invited him into their summer lodgings. But these lodgings are never referred to as chalets, even though strictly speaking that is what they must have been – huts above the tree-line where dairy farmers stayed for the summer to milk their cows and make cheese. In the novel as a whole, the word “chalet” appears only five times, always in reference to the place of the original amorous encounter.

It seems hardly credible that a few sentences, culled from different parts of a work of fiction, should have given rise to the longstanding craze both for the Swiss chalet and for the Alpine landscape – and indeed to an entire fascination for pastoralism in a mountain setting. Yet Rousseau’s vividly accurate descriptions of the mountain region above Vevey made the town and its backdrop into a place of pilgrimage. By the late nineteenth century, it had become a popular tourist destination for the international elite.24

The Swiss Chalet and Its Different Guises

The effect of Rousseau’s novel was immediate. As early as the second half of the eighteenth century, the Swiss chalet appeared as a garden folly, most notably in France. In the nineteenth century its popularity continued with the chalet style, characterized by fancy wood-carved roof trimmings, balconies and facade decorations, all purported to be Swiss. The chalet style was widely copied, not only in Europe, where it became the popular style of the new leisure class – as demonstrated in the architecture of spa resorts, villas, seaside hotels and railway stations – but also in North America, and in mountain resorts in British India.25

The hype surrounding the Swiss chalet also created ethnographic interest, not only among Europe’s artistic and intellectual elite who travelled to Switzerland to see the real Swiss chalet with their own eyes, but also among the Swiss political class who needed a national icon to represent the new Swiss nation-state, founded in 1848.26 The search for the authentic Swiss chalet resulted in a rather different model from that of the original garden folly, with its steep thatched roof, or that of the of the chalet style, with its many varieties of gable trimmings. By the early twentieth century, it was the shallow slope of the roof that became the main authentically Swiss characteristic, one which still allows chalets to be identified as such today.

The Garden Folly

Although only a few images and descriptions of the early examples of the chalet as garden folly exist, it is evident that they bear no resemblance to any of the regional varieties of Swiss chalets now known ().27 What they resembled most was the English country cottage, their thatch a direct reference to Rousseau’s description in Julie.

Figure 3 Map from the 1950s showing the regional varieties of farmhouse in Switzerland. Number 4 is the only one with a steeply pitched thatched roof; from Richard Weiss, Häuser und Landschaften der Schweiz (Erlenbach-Zurich: Eugen Rentsch, 1959), pls I–II. Reproduced with permission of the artist Hans Egli.

An English admirer of Rousseau’s was allegedly the first to have built a Swiss chalet as a garden feature on his estate, in the early 1760s.28 Three English editions of Julie were published in 1761, the year of the book’s first appearance, with twelve more before 1812, when its popularity waned.29 Rousseau spent a short period of exile in England from 1765 to 1767, when his radical religious, political and social ideas caused him to be banished not only from his native Switzerland but also briefly from France.30 Another version of the Swiss chalet was built in 1767 in the gardens of a French admirer north of Paris, in order to provide a home for Rousseau on his return.31 Both chalets were integrated within newly fashionable landscape gardens, arranged in settings with trees and ponds. They paid tribute to Rousseau as a novelist and also to romantic love and the passions of the heart more generally.

Because of strict censorship laws in France, on the grounds of morality and religion, there were fewer editions of Julie in its original French than in English – the 1761 edition was published not in France, but in Amsterdam32 – but this did not diminish the book’s notoriety. In 1783, the French queen Marie-Antoinette commissioned the construction of a scenic group of chalets known as La petite Suisse (Little Switzerland) on the new Trianon extension of the Versailles estate. The architect Richard Mique followed the novel’s description closely, and included not only a hamlet of several chalets with thatched roofs set in a landscape of trees and a pond but also a water mill to suggest the sound of running water, and a thatched dairy farm ().33 To perfect the illusion, Swiss cows and even a pretty Swiss dairymaid were included. According to a nineteenth-century source, the dairymaid “fell ill almost to death with nostalgia.”34 Here, nostalgia as homesickness and the hype over the Swiss chalet were directly intertwined.

Figure 4 “Ferme du hameau de la Reine.” Photograph by Starus, 16 June 2011. Available from Wikimedia under licence CC-BY-SA 3.0.

The royal interpretation of the Swiss chalet became best known for the fashion trend the queen created with her “shepherdess outfit,” a recreation of the bosom-revealing dress of the female mountain inhabitants so lyrically described by Julie’s lover.35 Despite this, in a guidebook published less than a century later, the thatched royal chalets were no longer described as Swiss, but as cottages typical of the French coastal region of Normandy.36 The thatch-roofed “Swiss chalets” shown in late eighteenth-century books on garden architecture are almost always interpreted by historians of such architecture as “influenced by the English ‘cottage’-style,” despite their label.37 By the end of the nineteenth century, the link to the novel’s description of the chalet was long forgotten. Exempt from its Swiss connection, Versailles’ royal hamlet became the supreme example of the glorification of pastoralism in general.38

A Search for The Authentic Swiss Chalet

Rousseau’s novel also initiated more scholarly interest in the geography of the Alpine regions and their vernacular architecture. Switzerland in the late eighteenth century was not yet a federal state, but a number of semi-autonomous cantons; contemporary studies revealed that there was no single Swiss house type, but a huge variety of farm and town houses. However, the type these studies omitted was the genuine chalet – the mountain hut or, in Swiss German, Sennhütte – which they considered too primitive to be noteworthy.39

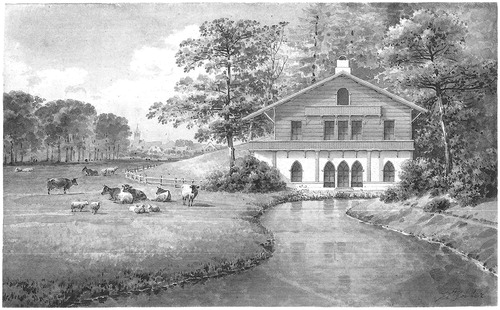

The nineteenth century also witnessed a slow pan-European search for the authentic Swiss chalet. Garden chalet designs early in the century still echoed Rousseau’s description in the novel, but they also strove to look more properly Swiss, as the work of Dutch architect Jan David Zocher Jr. illustrates. Zocher, who trained at the Ecole Impériale in Napoleonic France, was still highly influenced by eighteenth-century classics on garden architecture when he designed three “Swiss chalets,” one on each of the estates of a wealthy Dutch banker, between 1823 and 1836.40 All three looked much more like “real” Swiss farmhouses than their eighteenth-century predecessors, with projecting slate roofs, wood-carved galleries, whitewashed base and wood-clad facades. Following Rousseau, all three were set amongst trees, next to meadows bordering a stream.41 The more authentic appearance of Zocher’s so-called chalets has been attributed to the numerous studies of Switzerland published in the early nineteenth century, and to the fact that Zocher had actually travelled through Switzerland on his return from Rome in 1814.42 Although he crossed the regions where thatch was common, he identified the farmhouse type with wooden roof shingles as the most typically Swiss. Faithful copying, though, does not seem to have been his main objective, as in his first chalet design he also integrated fashionable neo-gothic windows ().

Figure 5 Watercolor by the Dutch garden architect Jan David Zocher to present his design of a Swiss chalet featuring neo-gothic windows, 1823; from Constance D. H. Moes, Architectuur als sieraad van de natuur (Rotterdam: Nederlands Architectuurinstituut, 1991), pl. 20. Private collection. Every effort has been made to trace the current copyright holder but they remain unknown.

Zocher was by no means the only one interested in the real Switzerland. Julie had sparked a passion for everything Swiss, and a pilgrimage to Switzerland became a must for the European artistic elite, in particular for those interested in its exotic architecture. English admirers such as Lord Byron and John Ruskin were among the first to visit the scenes of the Nouvelle Heloïse in search of an unspoiled Arcadia.43 Ruskin and the Frenchman Eugène Viollet-le-Duc were the most influential nineteenth-century writers on the authentic Swiss chalet, whose publications not only changed its popular image but also reflected prevailing academic ideas on the history of European civilization.44

Ruskin was fifteen when he visited Switzerland in 1833. Four years later he published his impressions in a series of articles titled The Poetry of Architecture (1837–38).45 In exalted prose he described his first encounter with a “real” Swiss cottage ():

Figure 6 John Ruskin’s drawing of what he calls a “real Swiss cottage,” 1833; from John Ruskin, “The Poetry of Architecture” [1837], in The Complete Works of John Ruskin, Vol. I (New York: National Library Association eBook, 2006).

![Figure 6 John Ruskin’s drawing of what he calls a “real Swiss cottage,” 1833; from John Ruskin, “The Poetry of Architecture” [1837], in The Complete Works of John Ruskin, Vol. I (New York: National Library Association eBook, 2006).](/cms/asset/a2c7dbfe-0e89-4fbc-99d6-f51139a818dc/rfac_a_1477672_f0006_b.jpg)

Well do I remember the thrilling and exquisite moment when first, first in my life (which had not been over long), I encountered, in a calm and shadowy dingle, darkened with the thick spreading of tall pines, and voiceful with the singing of a rock-encumbered stream, and passing up towards the flank of a smooth green mountain […] in this calm defile of the Jura, the unobtrusive, yet beautiful, front of the Swiss cottage. I thought it the loveliest piece of architecture I had ever had the felicity of contemplating; yet it was nothing in itself, nothing but a few mossy fir trunks, loosely nailed together, with one or two gray stones on the roof […].46

He went on to criticize the inauthentic appearance of the “Swiss cottages” being built in Britain:

How different is this from what modern architects erect, when they attempt to produce what is, by courtesy, called a Swiss cottage. The modern building known in Britain by that name has very long chimneys. […] Its gable roof slopes at an acute angle. […] Its walls are very precisely and prettily plastered. […] Now, I am excessively sorry to inform the members of any respectable English family, who are making themselves uncomfortable in one of these ingenious conceptions, under the idea that they are living in a Swiss cottage, that they labor under a melancholy deception […].47

If the core characteristics of the invented Swiss chalet are familiar, Ruskin’s choice of the word “melancholy” to describe their fakery is particularly interesting. Nostalgia as homesickness was considered a severe form of melancholy, so Ruskin speaks here of the idea of the fake chalet as a nostalgic deceit.

Ruskin is the first to make a clear distinction between the Swiss chalet proper – the simple hut high in the mountains – and the elaborately decorated farmhouse in the valley.

The life of a Swiss peasant is divided into two periods; that in which he is watching his cattle at their summer pasture on the high Alps, and that in which he seeks shelter from the violence of the winter storms in the most retired parts of the low valleys […]. The Alpine or summer cottage, therefore, is a rude log hut, formed of unsquared pine trunks, notched into each other at the corners. The roof being excessively flat […] is covered with fragments of any stone. […] That is the “châlet.”48

The winter residence, which Ruskin calls the real Swiss cottage, is much more elaborate. Ruskin tells us that

[t]he roof is always very flat, generally meeting at an angle of 155’, and projecting from 5 ft. to 7 ft. over the cottage side. […] That this projection may not be crushed down by the enormous weight of snow, […] it is assisted by strong wooden supports. […] The galleries are generally rendered ornamental by a great deal of labor bestowed upon their wood-work. […] The door is always six or seven feet from the ground […] that it may be accessible in snow; and is reached by an oblique gallery. […] The base of the cottage is formed of stone, generally whitewashed.49

Ruskin also admires the industry of the Swiss peasants in adorning and looking after their winter home:

there is nothing to be found the least like it in any other country. The moment a glimpse is caught of its projecting galleries, one knows that it is the land of Tell […] and the traveler feels, that were he indeed Swiss-born and Alp-bred, a bit of carved plank, meeting his eye in a foreign land, would be as effectual as a note of the “Ranz des Vaches” upon the ear.50

We are back with the legendary impact of the Kühreihen song on Swiss mercenaries. By comparing it to the visual effect of the carved woodwork, Ruskin explicitly links the love for the Swiss chalet with homesickness, and thus Fernweh with Heimweh.

If we use Ruskin’s definition, Zocher’s garden buildings were not chalets but farmhouses or cottages. It was the farmhouse that became the dominant and decorative version of the so-called Swiss chalet as garden feature in European garden architecture of the first half of the nineteenth century. Ruskin himself, however, fiercely objected to any imitation of the Swiss cottage outside its native context: “The Swiss cottage […] is not a thing to be imitated […] when out of its own country,” for “the cottage enhances the wildness of the surrounding scene.”51 Ruskin’s conviction that the exotic was not to be imported, but had to be enjoyed in its own surroundings, drove his own travels; it was a view that also gave rise to tourism on a much grander scale in the late nineteenth century.

The International Chalet Style

Examples of the so-called “chalet style” of the late nineteenth century, from Norway to Portugal and beyond, are hardly typically Swiss in appearance, let alone based on the Swiss chalet, whether farmhouse or hut.52 The style was a mix of exotic, regional elements, not only Swiss or German but also Italian or Russian, and occasionally oriental, in combination with gothic elements. Despite its diversity of sources, it has certain unifying characteristics, in particular steeply pitched roofs and wood-carved gable decorations. Half timbering, turrets and towers are also familiar features.53

In Norway the chalet style transformed into the country’s national style when mixed with indigenous dragon elements.54 The English exported it to Jamaica and New Zealand, and also to India, as the preferred style for colonial hill stations.55 In Europe, it became the style associated with leisure and tourism, as exemplified in the design of seaside villas such as those of Mers-les-Bains in Normandy (), Cascais in Portugal or villa estates in the Dutch dunes, as well as hotels and railway stations.56 If Rousseau’s chalet had been interpreted as a symbol of the harmony between man and Nature, the ubiquitous chalet style, with its mix of exotic, regional and gothic elements, was perfect to evoke the idea of scenic travel and the discovery of strange and unknown landscapes.

Figure 7 The international chalet style, as exemplified in the seafront villas of the French seaside resort of Mers-les-Bains, Normandy. Photograph by Inmacor, Moment Collection, Getty Images.

In Switzerland itself, the attempt to create a national Swiss architectural identity after 1848, when its previously autonomous regions were joined into one federal state, meant that regional diversity was eschewed.57 For a more unified image, the Swiss turned initially to foreign-inspired examples of the chalet style. At the World Exhibition in Paris in 1867, the new nation presented itself through a strange collage of villas and villa castles, and one garden folly, all embellished with wood-carved decorations in a pastiche of chalet-style motifs. By the time of the Paris exhibitions of 1889 and 1900, however, Switzerland presented a more realistic mix of town and farmhouses from different regions, within a setting of plastered mountains.58 Eventually the picturesque farmhouse of the Bern region was selected to represent Swiss national identity, thus initiating an ongoing rivalry between Bern and other regions with different house types.59

In imitation of their foreign admirers, the Swiss also began to refer to their own farmhouses as chalets. The international chalet hype resulted in a conscious revival of vernacular architecture in Switzerland itself. The early villas designed by the young Swiss architect Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, later to become Le Corbusier, in his hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds in the Jura had a definite chalet look. Built between 1906 and 1908, they had the pointed roofs characteristic of the international chalet style, though each represented a different regional chalet type.60 In the course of the twentieth century, however, it was the chalet type with the shallow sloping roof that became the new European fashion, and icon of Swiss identity.

The Swiss Chalet As Europe’s Primitive Hut

In the popular imagination, the shift from chalet as monumental suburban villa in the chalet style to rude log hut in the mountains was brought about by another Swiss-authored work of fiction, Johanna Spyri’s Heidi. Published as a children’s book in 1880, Heidi reflected a religiously inspired interest in the Alps as locus of Nature’s divine sublimity and healing environment for body and soul suffering from worldly, urban overstimulation.61 The book’s publication coincided with a craze for constructing sanatoria and mountain resorts in Switzerland.62 More generally, Heidi echoed the later nineteenth-century passion for honest, rustic simplicity and the appreciation of the noble handicraft of woodwork in contrast to industrial production.63 It was thus a reflection of the concurrent academic discourse on the origins and developmental stages of Western civilization and its material culture.

Viollet-le-Duc’s Histoire de l’habitation humaine depuis les temps préhistoriques jusqu’a nos jours (1875) is one of a number of architectural writings to celebrate the chalet proper as the remnant of a primordial past, as the primitive hut which is the revered origin of Western architecture.64 The Frenchman noted that the mountain chalets of Switzerland not only looked the same as the huts on the slopes of the Himalayas but also were constructed in the same manner (). He shared the then-dominant view that Europe’s civilization was determined by the Aryan race whose descendants had migrated from the Himalayas, cradle of Aryan culture, to the heart of Europe. In this, he followed the theory of cultural diffusion in which similarity in material culture was proof of this migration.65 The Aryan chalet, both Alpine and Himalayan, was classified as the archetypal house of Homo sapiens.66

Figure 8 Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, “A Himalayan Chalet,” drawing; from W. S. B. Dana, The Swiss Chalet Book: A Minute Analysis and Reproduction of the Châlets of Switzerland, Obtained by a Special Visit to that Country, Its Architects, and Its Châlet Homes (New York: William T. Comstock Co., 1913), 17.

Spyri’s story encapsulates these nineteenth-century concerns in presenting a return to the root of civilization as healing. Five-year-old orphan Heidi is sent to live with her solitary grandfather who has taken permanent residence in his chalet high in the Alps. Heidi soon feels at home in the mountains, grows fond of her grumpy grandfather and makes friends with the young goatherd, Peter. Aged eight, she is sent back to the city to get an education, but falls seriously ill. The doctor recognizes increasing homesickness and advises that she should be sent back to her grandfather.67 Her speedy recovery convinces the doctor of the mountain lifestyle’s health-promoting qualities; ostensibly to keep her company, he sends Heidi’s crippled friend, a spoilt, upper-class girl from the city, to join her. The friend, too, is miraculously healed.68 Heidi brings together Heimweh and Fernweh in the illnesses of Heidi and her friend; it links both types of nostalgia to a longing for the Swiss Alps and the Swiss chalet, and it makes clear the healing, invigorating properties of mountain dwelling in contrast to the unhealthy enervation of city life.

Like Rousseau’s Julie, Heidi too had an immediate international impact due to its English translation.69 Thanks to many adaptations, illustrated versions, and film and television productions, the story of Heidi continues to resonate worldwide, now with ready-made visual imagery. The first film, produced in 1937 with Shirley Temple in the title role, was the most internationally famous. However, a film produced as late as the 1970s and made in the Swiss village of Maienfeld has been more influential from a specifically Swiss perspective – a local tourist promoter branded the region “Heidiland.” Due to the popularity of an animated version of Heidi made in Japan in 1974, the region still attracts Japanese tourists to this day, drawn there by a modern version of Fernweh.70

The success of Heidi, first as a book, then on screen, reinvigorated the craze for Swiss chalet-building across Europe and beyond, this time associated with a healthy, youthful lifestyle rather than as a lovers’ nest.71 In the 1940s, influenced particularly by the first film version, the popular image of the chalet changed definitively from picturesque Swiss farmhouse into a simple log hut with an almost flat roof. Log huts quickly became popular, almost commonplace.72 The architecture of even the most modern ski-resorts throughout the world pays tribute to the Swiss chalet. In its powerful imagery and historic link to mountain scenery the Swiss chalet remains a well-known topos, as well as a touristic asset, even if the chalet itself is now in a completely different guise from its original in Rousseau’s novel.

Switzerland: A Journey into Europe’s Past

The exotic image of Switzerland and in particular its mountains had to do with their geographical position. They formed an obstacle for wealthy Northern European tourists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries traveling on their Grand Tour via Paris and Switzerland to Rome, seen by some as a symbol of civilization’s perfectibility, by others as already indicative of its decline.73 The Alps represented Europe’s unexplored interior, inhabited by the fierce Helvetian race, known to be a poor and superstitious people.74 For Rousseau, they were noble savages, primitive yet honest, whose rustic simplicity, in harmony with its setting, could save a now-corrupted civilization.75 For proponents of the nineteenth-century evolutionary view who perceived European civilization as a process heading towards ever-greater perfection, driven by science, reason and calculation, they were a backward people, still living in the darkness of the Middle Ages.76 The pockets of primitivism within Europe, the Swiss Alps among them, were explained by their isolation, which had halted their progress and, in evolutionary terms, left them behind.77

Nineteenth-century tourism to the Alpine regions thus represented a journey into Europe’s past. For Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc, proponents of cultural diffusionism, it meant a search for precious material traces of an ancient civilization long gone. In the evolutionary view, it meant travelling back to primitive medieval times.78 The neo-gothic windows of Dutch architect Zocher’s first “Swiss chalet” of 1823 indicate his romanticized evolutionary understanding.79 The mix of neo-gothic details combined with references to other regions distant in time or place that was characteristic of the late nineteenth-century international chalet style was an appreciation of both rustic simplicity and exoticized primitivism. Although the local countryside or the coast was not as exotic as Switzerland, to visit even these places was to travel into Europe’s pre-industrial past.80

While in academic circles the evolutionary perspective of the advancement of civilization was dominant, in artistic milieus the idea of the redemptive possibilities of an uncorrupted past prevailed.81 The fascination of many Romantic composers with the song of the Kühreihen, it has been suggested, was an expression of their own longing for a lost past of rustic innocence.82 The nineteenth-century medical assessment of homesickness, though, reflected the evolutionary standpoint in viewing it as a mental affliction of people who lagged behind in the civilizing process.83 Longing for the home and kin one had left behind was seen as a psychological condition of backwardness and immaturity.84

According to twentieth-century modernist critique, still steeped in evolutionary thinking, nostalgia was escapist and backward-looking. However, in the utopian agendas of the activist student generation of the 1960s and 1970s it was reappraised, and the search for the uncorrupted again became resonant. This generation not only celebrated the material remnants of an idealized pre-industrial past but also searched more widely for exotic and pristine regions. Their Fernweh brought them to India and Afghanistan, whose mountains took on the appeal that the Alps had held for their nineteenth-century forebears. As the locus of the exotic shifted to more distant places, Switzerland and the Swiss chalet lost their distinctive nostalgic appeal.

Conclusions

Nostalgia’s initial link to Switzerland and the mountains, as a place longed for by Swiss mercenaries, was reinforced in the late eighteenth century by the European elite’s passion for the Swiss chalet. Rousseau’s Julie and his description of the legendary impact of the Ranz des Vaches brought about a craze for all things Swiss in nineteenth-century literature, music, arts and architecture. Poetry and painting glorified the sublimity of the Alpine mountains and the harmony between man and Nature. Celebrated writers and composers found inspiration in the heroism of the legendary medieval freedom fighter Wilhelm Tell. The erotic and feminine connotations of the chalet, including the primitive but honest simplicity of the Swiss mountain inhabitants, were popular ingredients of several comic operas. And the elegant wooden structures of the Swiss chalet enchanted intellectuals such as Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc and also a much wider audience for whom they were exotic and picturesque.

Europe’s long love affair with the Swiss chalet was sparked by the potent imagery created in fiction. Although both Julie and Heidi were written by native Swiss authors, the Swiss chalet in its many architectural guises – garden folly, chalet-style villa or rude log hut – that Rousseau and Spyri inspired was a foreign fantasy of an exotic Switzerland. The nineteenth-century fascination for the Alpine regions was determined by their splendid isolation, which had halted the passing of time. As a consequence Alpine mountain-dwellers were believed to live in a primordial age, untouched by civilization, which meant that for some they were uncorrupted, while for others they were primitive and backward.

The artistic elite was fascinated by the uncorruptedness of the inhabitants, and by the idea that the origin of Western civilization might be reflected in the prime material manifestation of the Swiss chalet. The academic view was less benign. The nineteenth-century medical understanding of nostalgia, at that time an affliction still associated with mountain-dwellers, was that it was a condition of the immature, primitive minds of those who still lived in the historic past. Nostalgia’s original meaning of a craving for the Swiss mountains as home shifted to emphasize its backward-looking orientation. In this way, a spatial dislocation became temporal. By studying nostalgia’s links with Switzerland, it becomes clear that time has gradually obscured the importance of place in our understanding of the term.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Irene Cieraad

Irene Cieraad is a cultural anthropologist and senior researcher in the Department of Architecture (Chair of Interiors), Delft University of Technology. She is editor of At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space (Syracuse University Press, 2006).

Notes

1 The Oxford English Dictionary presents the shifts of meaning of nostalgia in reverse order: 1. sentimental yearning for a period of the past, 2. regretful or wistful memory of an earlier time, 3. severe homesickness.

2 Johannes Hofer, “Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia by Johannes Hofer, 1688,” trans. Carolyn Kiser Anspach, Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine no. 2 (1934): 376–391.

3 Annika Lems, “Ambiguous Longings: Nostalgia as the Interplay among Self, Time and World,” Critique of Anthropology 36, no. 4 (2016): 423; Susan J. Matt, Homesickness: An American History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 25–27.

4 Auguste Jansen, Considérations sus la nostalgie [sic] (Gand: Hebbelynck, 1869), 12–13.

5 Joseph Rykwert, On Adam’s House in Paradise: The Idea of the Primitive Hut in Architectural History (London: Academy Editions, 1972).

6 In English there is no simple translation for Fernweh. In Southern European languages the word “nostalgia” is used often in combination with “far-away countries” (Spanish: nostalgia de lo lejanos; Italian: nostalgia di paesi lontani; Portugese: saudades de longes terras).

7 Michael Kraus and Vera Kraus, Family Album for Americans: A Nostalgic Return to the Venturesome Life of America’s Yesterdays (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1961), is to my knowledge the first publication to refer in its title to the time-bound interpretation of nostalgia. See also Fred Davis, Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia (New York: Free Press, 1979), and Michael Pickering and Emily Keightley, “The Modalities of Nostalgia,” Current Sociology 54 no. 6 (2006): 922.

8 Irene Cieraad, “Memory and Nostalgia at Home,” in The International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, ed. Susan Smyth (Oxford, Elsevier, 2012), 4: 262–267.

9 Davis, Yearning for Yesterday; David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 4–13; David Lowenthal, “Nostalgia Tells It Like It Wasn’t,” in Imagined Past: History and Nostalgia, eds. Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), 18–32; Chase and Shaw, Imagined Past, 6–8.

10 Anthony Vidler, The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 63–67.

11 I owe much of the information on the Swiss chalet to Christina Horisberger, Das Schweizer Chalet und seine Rezeption im 19. Jahrhundert. Ein eidgenössischer Beitrag zur Weltarchitektur? Thesis, Lizentiatsarbeit der Philosophischen Fakultät I der Universität Zürich, 1999. She was so kind to send me a copy of her work.

12 Annemarie de Waal Malefijt, Images of Man: A History of Anthropological Thought (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974), 116–180.

13 Helmut Illbruck, Nostalgia: Origins and Ends of an Unenlightened Disease (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2012), 31–35; Clive H. Church and Randolph C. Head, A Concise History of Switzerland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 37, 63, 68.

14 Lems, “Ambiguous longings,” 423–425; Fritz Frauchiger, “The Swiss Kühreihen,” Journal of American Folklore 54, nos. 213–214 (1941): 121–131.

15 Hofer, “Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia.”

16 Ibid., 381.

17 Ibid., 389.

18 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dictionnaire de Musique (Paris: La Veuve Duchesne, 1764), 317, 405.

19 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Julie, or the New Heloise: Letters of Two Lovers Who Live in a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps [1761], trans. and annotated Philip Stewart and Jean Vaché (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997).

20 Stewart and Vaché, translators of the most recent English edition of Julie, claim that the novel introduced the word “chalet” into French; ibid., 631. However, according to architectural historian Pérouse de Montclos, the word was already in French use in 1723 to mean a primitive lodging in the mountains where dairy farmers stayed for the summer to milk their cows and make cheese; Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, “Le chalet à la Suisse. Fortune d’un modèle vernaculaire,” Architectura 17, no. 1 (1987): 76.

21 Rousseau, Julie, 92 (emphasis added).

22 In due course, thatched roofing became rare as it was replaced by less flammable materials. In an overview of twenty-one regional Swiss house types in Switzerland in the 1950s, Richard Weiss noted only one with a thatched roof in the canton of Aargau; Richard Weiss, Häuser und Landschaften der Schweiz. (Erlenbach-Zurich: Eugen Rentsch, 1959), pls I–II.

23 Rousseau, Julie, 63–65 (emphasis added).

24 Ibid., Julie, 23, 63–65. Donald Geoffrey. Charlton, New Images of the Natural in France: A Study in European Cultural History 1750–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 32–40, 59.

25 Andrew Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses [1850] (New York: Da Capo, 1968); Margaret Hayford O’Leary, Culture and Customs of Norway (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2010); Dane Keith Kennedy, The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

26 Felicity Rash, “Early British Travelers to Switzerland 1611–1860,” in Exercises in Translation: Swiss–British Cultural Interchange, eds. Joy Charnley and Malcolm Pender (Bern: Peter Lang, 2006), 109–138; Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet; Church and Read, Concise History of Switzerland.

27 Weiss, Häuser und Landschaften der Schweiz, 11.

28 The allegation warrants archival research; see Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 74.

29 Stewart and Vaché in Rousseau, Julie, 649.

30 Leo Damrosch, Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2005), 432; Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: The Science of Freedom (New York: W. W. Norton, 1977), 72; Stewart, “Introduction,” in Rousseau, Julie, ix–xxi.

31 Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 34–38, figs. 5, 6.

32 Stewart and Vaché in Rousseau, Julie, 649–650.

33 Béatrix Saule and Daniel Meyer, Versailles: A Guide for Visitors (Versailles: Art Lys, 2000), 92–93.

34 William Gifford, William Macpherson et al., “French Patriotic Songs,” The Quarterly Review 130–131 (1871): 109.

35 Rousseau, Julie, 67.

36 Michel Vernes, “Le chalet infidèle ou les dérives d’une architecture vertueuse et de son paysage de rêve,” Revue d’histoire du XIX siècle 32, no. 1 (2006): 122. See also Núria Perpinyà, “European Romantic Perception of the Middle Ages: Nationalism and the Picturesque,” Imago Temporis, Medium Aevum 6 (2012): 23–47, and Pierre André Lablaude, The Gardens of Versailles (Paris: Scala, 2005).

37 Constance D. H. Moes, Architectuur als sieraad van de natuur (Rotterdam: Nederlands Architectuurinstituut, 1991), 111.

38 The pastoralism pertained only to the exterior; the illusion created in the interior of the buildings was far from pastoral.

39 Pérouse de Montclos, “Chalet à la Suisse,” mentions Jacob-Samuel Wyttenbach, Vues remarquables des montagnes de la Suisse (Bern: Wagner, 1776), Baron de Zurlauben, Tableaux de la Suisse ou voyage pittoresque fait dans les treize cantons et états alliés du corps helvétique (Paris: Lamy, 1780–86) and Wilhelm Gottlich Becker, Taschenbuch fuer Gartenfreunde (Leipzig: Voss und Compagnie, 1797).

40 Nelly Jap-Tjong, “Een ‘Arcadiër’ in Amsterdam en Kennemerland: Adriaan van der Hoop (1778–1854),” in Beelden van de Buitenplaats: elitevorming en notabelencultuur in Nederland in de negentiende eeuw, ed. Rob van der Laarse and Yme Kuiper (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2005), 71–88.

41 Jap-Tjong, “Een ‘Arcadiër’ in Amsterdam en Kennemerland,” 84–87; Moes, Architectuur als sieraad van de natuur, 110.

42 Moes, Architectuur als sieraad van de natuur, 112.

43 Rash, “Early British Travelers.”

44 Pérouse de Montclos, “Chalet à la Suisse;” Vernes, “Chalet infidèle;” Perpinyà, “European Romantic Perception.”

45 John Ruskin, “The Poetry of Architecture” or “The Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National Character” [1837], in The Complete Works of John Ruskin, Vol. I (New York: National Library Association e-book, 2006).

46 Ibid., 39 (emphasis added).

47 Ibid. (emphasis added).

48 Ruskin is mistaken in adding a circumflex to the “a” of “chalet.” Following Ruskin, this hypercorrection is often made as foreigners assume a relation between the words “château” (castle) and “chalet” (emphasis added).

49 Ibid., 40–41 (emphasis added).

50 Ibid., 43. Wilhelm Tell was Switzerland’s medieval patriotic hero, a peasant who fought against the tyranny of his foreign overlords (emphasis added).

51 Ibid., 46, 105 (emphasis added).

52 Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 4–6.

53 Eugen Gugel, Architectonische vormleer. Vierde deel: Hout- en vakwerkbouw (The Hague: De Gebroeders van Cleef, 1888), pl. 34; Ireen Montijn, Naar buiten! Het verlangen naar landelijkheid in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw (Amsterdam: SUN, 2002), 109–121; Vernes, “Chalet infidèle,” 128–129.

54 Hayford O’Leary, Culture and Customs of Norway, 165–202.

55 According to Kennedy, Magic Mountains, 105, the hill stations’ architecture “looked like a cross between a Victorian garden villa and a Swiss chalet;” it was “a miserable attempt to unite the Swiss cottage with the suburban gothic.” Thanks to Christian Brunner of ETH Zurich for alerting me to the Indian hill stations.

56 Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 7; Gugel, Architectonische vormleer, pl. 21; Johannes De Haan, Villaparken in Nederland. Een onderzoek een onderzoek aan de hand van het villapark Duin en Daal te Bloemendaal 1897–1940 (Haarlem: Schuyt, 1986). In North America, the Swiss chalet style, together with the Italian or Tuscan style, in the nineteenth century was not associated with tourism and leisure but recommended for its rural simplicity as best suited for cottages and farmhouses; Downing, Architecture of Country Houses.

57 Church and Head, Concise History of Switzerland, 162–192.

58 Pérouse de Montclos, “Chalet à la Suisse,” 95; Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 48–51; Stanislaus Von Moos, Nicht Disneyland und andere Aufsätze über Modernität und Nostalgie (Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2004), 21–22.

59 Horisberger, Schweizer Chalet, 101–102. For the sake of the argument, I have simplified Horisberger’s more subtle analysis.

60 The roof shape of Villa Jaquemet, Chemin de Pouillerei 8, resembles the chalet type of the canton of Fribourg; that of Villa Stotzer at number 6, together with its rough stone base, echoes the chalet of the Italian-speaking Ticino region; Weiss, Häuser und Landschaften der Schweiz, I–II (and shown here as Figure 3).

61 Johanna Spyri, Heidi. Lehr- und Wander Jahre: eine Geschichte für Kinder und solche, die Kinder liebhaben [1880] (Zurich: Werd, 2001).

62 Susan Barton, Healthy Living in the Alps: The Origins of Winter Tourism in Switzerland, 1860–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008).

63 Irene Cieraad, “Traditional Folk and Industrial Masses,” in Alterity, Identity, Image: Selves and Others in Society and Scholarship, ed. Raymond Corbey and Joep T. Leerssen (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1991), 17–36.

64 Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Histoire de l’habitation humaine depuis les temps préhistorique jusqu’à nos jours (Paris: J. Herzel & Cie, 1875). Another example of such architectural writing might be Gugel’s Architectonische Vormleer. In echoing Ruskin on the ancient origins of the Swiss chalet, Gugel traced the history of the Alpine regions of Switzerland back to ancient times; the chalet’s shape resembled, in his view, the ancient architecture of Roman dwellings and temples. See also William S. B. Dana, The Swiss Chalet Book: A Minute Analysis and Reproduction of the Châlets of Switzerland, Obtained by a Special Visit to that Country, Its Architects, and Its Châlet Homes (New York: William T. Comstock Co., 1913), 13–17.

65 De Waal Malefijt, Images of Man, 116–180.

66 Pérouse de Montclos, “Chalet à la Suisse,” 82.

67 Maria Nikolajeva, “Tamed Imagination: A Re-reading of Heidi,” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 25 no. 2 (2000): 68–75.

68 Rafael Matos-Wasem, “The Good Alpine Air in Tourism Today and Tomorrow: Symbolic Capital to Enhance and Preserve,” Journal of Alpine Research 93 no. 1 (2005): 105–113.

69 Johanna Spyri, Heidi (London: W. Swan Sonnenschein, 1882).

70 Switzerland also attracts increasing numbers of Indian tourists, no doubt because most of Bollywood’s romantic scenes are shot in the country. In a way, Bollywood movies replicate Rousseau’s eighteenth-century link between mountains and secret romantic love.

71 In the United States, the chalet blended with the bungalow; Bruno Giberti, “The Chalet as Archetype: The Bungalow, the Picturesque Tradition and Vernacular Form,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 111, no. 1 (1991): 54–64.

72 I am struck by the omnipresence of the chalet in the Basque Country of northern Spain. Its popularity seems to have political roots and to be associated with that of Friedrich von Schiller’s play Wilhelm Tell (1804). In Schiller’s portrayal, Tell personified the struggle for freedom of the Swiss regions. His story seems to have resonated with Basque separatist ideals and it continues to lead to a proliferation of chalets.

73 John Towner, “The Grand Tour: A Key Phase in the History of Tourism,” Annals of Tourism Research 12 (1985): 297–333, esp. 303, 314–315, 318.

74 Vernes, “Chalet infidèle,” 114–116; Giberti, “Chalet as Archetype,” 57.

75 Charlton, New Images of the Natural in France.

76 Ibid., 92–105; see also Illbruck, Nostalgia, 19–20.

77 Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983); Cieraad, “Traditional Folk and Industrial Masses.”

78 Perpinyà, “European Romantic Perception,” 35.

79 For Zocher’s German contemporary, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, the Swiss chalet was an evolved, medieval expression of a Greek temple, as exemplified in Schinkel’s Swiss Cottage on Pfaueninsel, an island in the River Havel near Berlin; Horisberger, Schweitzer Chalet, 61–70.

80 The title of Lowenthal’s book, The Past is a Foreign Country, implies a similar idea. However, Lowenthal’s focus is on a critique of nostalgia’s profitability, whether in promoting visits to vulnerable heritage sites representing the past or in the merchandizing of the surrogate past, and not on the role of these attitudes towards the past in shaping our emotions. “If the past is a foreign country […] it has the healthiest tourist trade of all;” ibid., 4.

81 Ibid., 102.

82 The Ranz de Vaches, or Kühreihen, was an integral part of a number of operas on the topic of the chalet and romantic love, such as Adolphe Adams’s Le Châlet (1834) and Gaetano Donizetti’s Betly, o La Capanna Svizzera (1836), which were mainly based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s song piece Jery und Bätely (1780). See also Frauchiger, “Swiss Kühreihen;” and Lems, “Ambiguous Longings,” 423.

83 Jansen, Considérations sus la nostalgie; Matt, Homesickness, 28.

84 Matt, Homesickness, 8.

References

- Baron de Zurlauben (pen name of Jean Benjamin de la Borde). 1780–86. Tableaux de la Suisse ou voyage pittoresque fait dans les treize cantons et états alliés du corps helvétique. Paris: Lamy.

- Barton, Susan. 2008. Healthy Living in the Alps: The Origins of Winter Tourism in Switzerland, 1860–1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Becker, Wilhelm Gottlieb. 1797. Taschenbuch fuer Gartenfreunde. Leipzig: Voss und Compagnie.

- Charlton, Donald Geoffrey. 1984. New Images of the Natural in France: A Study in European Cultural History 1750–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chase, Malcolm, and Christopher Shaw, eds. 1989. Imagined Past: History and Nostalgia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Church, Clive H., and Randolph C. Head. 2013. A Concise History of Switzerland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cieraad, Irene. 1991. “Traditional Folk and Industrial Masses.” In Alterity, Identity, Image: Selves and Others in Society and Scholarship, edited by Raymond Corbey and Joep T. Leerssen, 17–36. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Cieraad, Irene. 2012. “Memory and Nostalgia at Home.” In The International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home, vol. 4, edited by Susan Smyth, 262–267. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Damrosch, Leo. 2005. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Restless Genius. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Dana, William, S. B. 1913. The Swiss Chalet Book: A Minute Analysis and Reproduction of the Châlets of Switzerland, Obtained by a Special Visit to that Country, Its Architects, and Its Châlet Homes. New York: William T. Comstock Co.

- Davis, Fred. 1979. Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York: Free Press.

- De Haan, Johannes. 1986. Villaparken in Nederland. Een onderzoek een onderzoek aan de hand van het villapark Duin en Daal te Bloemendaal 1897–1940. Haarlem: Schuyt.

- De Waal Malefijt, Annemare. 1974. Images of Man: A History of Anthropological Thought. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Downing, Andrew Jackson. 1968 [1850]. The Architecture of Country Houses. New York: Da Capo.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Frauchiger, Fritz. 1941. “The Swiss Kuhreihen.” Journal of American Folklore, 54, nos. 213–214: 121–131.

- Gay, Peter. 1977. The Enlightenment: The Science of Freedom. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Giberti, Bruno. 1991. “The Chalet as Archetype: The Bungalow, the Picturesque Tradition and Vernacular Form,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 111, no. 1: 54–64.

- Gifford, William, William Macpherson et al. 1871. “French Patriotic Songs,” The Quarterly Review nos. 130–131: 108–121.

- Gugel, Eugen. 1888. Architectonische vormleer. Vierde deel: Hout- en vakwerkbouw. The Hague: De Gebroeders van Cleef.

- Hayford O’Leary, Margaret. 2010. Culture and Customs of Norway. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Hofer, Johannes. 1934 [1688]. “Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia by Johannes Hofer, 1688,” translated by Carolyn Kiser Anspach. Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine no. 2: 376–391.

- Horisberger, Christina. 1999. Das Schweizer Chalet und seine Rezeption im 19. Jahrhundert. Ein eidgenössischer Beitrag zur Weltarchitektur? Thesis, Lizentiatsarbeit der Philosophischen Fakultät I der Universität Zürich.

- Illbruck, Helmut. 2012. Nostalgia: Origins and Ends of an Unenlightened Disease. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Jansen, Auguste. 1869. Considérations sus la nostalgie [sic]. Gand: Hebbelynck.

- Jap-Tjong, Nelly. 2005. “Een ‘Arcadiër’ in Amsterdam en Kennemerland: Adriaan van der Hoop (1778–1854).” In Beelden van de Buitenplaats: elitevorming en notabelencultuur in Nederland in de negentiende eeuw, edited by Rob van der Laarse and Yme Kuiper, 71–88. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren.

- Kennedy, Dane Keith. 1996. The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kraus, Michael, and Vera Kraus. 1961. Family Album for Americans: A Nostalgic Return to the Venturesome Life of America’s Yesterdays. New York: Grosset & Dunlap.

- Lablaude, Pierre André. 2005. The Gardens of Versailles. Paris: Scala.

- Lems, Annika. 2016. “Ambiguous Longings: Nostalgia as the Interplay among Self, Time and World,” Critique of Anthropology 36 no. 4: 419–438.

- Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lowenthal, David. 1989. “Nostalgia Tells It Like It Wasn’t.” In Imagined Past: History and Nostalgia, edited by Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw, 18–32. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Matos-Wasem, Rafael. 2005. “The Good Alpine Air in Tourism Today and Tomorrow: Symbolic Capital to Enhance and Preserve,” Journal of Alpine Research 93 no. 1: 105–113.

- Matt, Susan J. 2011. Homesickness: An American History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moes, Constance D. H. 1991. Architectuur als sieraad van de natuur. Rotterdam: Nederlands Architectuurinstituut.

- Montijn, Ileen. 2002. Naar buiten! Het verlangen naar landelijkheid in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw. Amsterdam: SUN.

- Nikolajeva, Maria. 2000. “Tamed Imagination: A Re-reading of Heidi,” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 25 no. 2: 68–75.

- Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie. 1987. “Le chalet à la Suisse. Fortune d’un modèle vernaculaire,” Architectura 17, no. 1: 76–96.

- Perpinyà, Núria. 2012. “European Romantic Perception of the Middle Ages: Nationalism and the Picturesque,” Imago Temporis, Medium Aevum 6: 23–47.

- Pickering, Michael, and Emily Keightley. 2006. “The Modalities of Nostalgia,” Current Sociology 54, no. 6: 919–941.

- Rash, Felicity. 2006. “Early British Travelers to Switzerland 1611–1860.” In Exercises in Translation: Swiss–British Cultural Interchange, edited by Joy Charnley and Malcolm Pender, 109–138. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1997 [1761]. Julie, or the New Heloise: Letters of Two Lovers Who Live in a Small Town at the Foot of the Alps, translated and annotated by Philip Stewart and Jean Vaché. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1764. Dictionnaire de Musique. Paris: La Veuve Duchesne.

- Ruskin, John. 2006. “The Poetry of Architecture” or “The Architecture of the Nations of Europe Considered in its Association with Natural Scenery and National Character” [1837]. In The Complete Works of John Ruskin, Vol. I. New York: National Library Association eBook.

- Rykwert, Joseph. 1972. On Adam’s House in Paradise: The Idea of the Primitive Hut in Architectural History. London: Academy Editions.

- Saule, Béatrix, and Daniel Meyer. 2000. Versailles: A Guide for Visitors. Versailles: Art Lys.

- Spyri, Johanna. 1880/2001. Heidi. Lehr- und Wander Jahre: eine Geschichte für Kinder und solche, die Kinder liebhaben [1880]. Zurich: Werd.

- Spyri, Johanna. 1882. Heidi. London: W. Swan Sonnenschein.

- Towner, John. 1985. “The Grand Tour: A Key Phase in the History of Tourism,” Annals of Tourism Research 12: 297–333.

- Vernes, Michel. 2006. “Le chalet infidèle ou les dérives d’une architecture vertueuse et de son paysage de rêve,” Revue d’histoire du XIX siècle 32, no. 1: 111–136.

- Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène. 1875. Histoire de l’habitation humaine depuis les temps préhistorique jusqu’à nos jours. Paris: J. Herzel & Cie.

- Vidler, Anthony. 1992. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Von Moos, Stanislaus. 2004. Nicht Disneyland und andere Aufsätze über Modernität und Nostalgie. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

- Weiss, Richard. 1959. Häuser und Landschaften der Schweiz. Erlenbach-Zurich: Eugen Rentsch.

- Wyttenbach, Jacob-Samuel. 1776. Vues remarquables des montagnes de la Suisse. Bern: Wagner.