ABSTRACT

Amidst the skyscrapers of many contemporary Chinese cities, commercial streets have emerged in traditional Chinese styles that serve as places to host festive celebrations and to satisfy everyday leisure and commercial needs. Buildings along these streets operate at one level as ritual “encasements” that frame festival processions, and thereby “speak” of ceremonial meanings. These framing devices constitute material remnants of past festival events, periodically reactivated as public spectacles or during momentary episodes of individual or collective recollection. This study explores themes relating to these intersections between building and festive occasion through an examination of two traditionally designed commercial streets in China. It argues that architecture in these two cases presents in different ways a “foregrounding” of festivals, in which participants are reminded of previous events. Architectural elements and their details serve as substitutes for words, recapitulating the verbal and gestural meanings of festivals through design language.

Introduction

This research explores the festive and symbolic meaning of ornamented facades in two cases of contemporary commercial streets in China that were built in traditional styles in the reform period after the 1980s. Both are intended as special places to host festivals and special events for visitors to experience and understand local histories, as well as accommodating commercial interests and everyday leisure purposes. The first street was designed and constructed to consciously mimic a historic built environment in the Jiangnan area in east China; the second is a renovation of a historic street in the borderlands of southwest China.

The Jiangnan area (which collectively refers to Jiangsu province, Zhujiang province and Shanghai) was historically famous for its bustling commercial activities that date back to the Song Dynasty (960–1279). At that time, many rich salt merchants in the region sponsored theaters in cities that attracted crowds of businessmen and other visitors from all over the country and promoted commercial activities in urban spaces. As Yue Meng describes it, this daily “urban festivity” in Suzhou during the Song Dynasty constituted a culture whose energy was “generated by a concentration of such urban settings, filled with crowds of businessmen, travellers, theatregoers, sightseers, small shopkeepers, ‘country bumpkins,’ rich ladies, prostitutes, and pickpockets.”1

Commercial activities in the Jiangnan area were well documented in famous historic paintings. Christian de Pee discusses artists’ representations of urban festivities in Suzhou, stating that the city was animated by the logic of livelihood within the cosmological cycle. It was the cosmological dimensions of “urban festivity” that connected two different phenomena: material prosperity on the one hand and cosmopolitan human vitality on the other.2 Similar urban festivities continued in the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1644 and 1644–1912), as discussed by Xiyuan Chen who adapted Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the “Carnivalesque” and explained how the Qing commercial streets provided a unified space for people from different social groups to mix freely during the Chinese traditional Yuanxiao Festival.3 Meng suggests that during the festivals and other special occasions depicted in traditional paintings, urban space was represented with two layers of meanings, the physical or worldly layer and the cosmological layer, which established an aesthetic connection between a prosperous city and the entire human world.4

In the same period, leisure became recognized as an integral part of everyday existence in Jiangnan. This change was associated with the emergence of a new social group in these commercial streets, the so-called “martial art heroes” who indulged in leisure activities in teahouses and restaurants rather than pursuing study. Their appearance in public spaces highlights a significant change in attitudes about official career paths through the civil service examination. This ubiquitous imperial examination had helped to shape many aspects of Chinese society since the Song dynasty, and was based on Neo-Confucian orthodoxy.5 New choices of leisure signified alternative life choices that were different from those based on common knowledge of the classics and its literary style.6

The word “festival” means either “a day or period of celebration, typically for religious reasons,” or “an organized series of concerts, plays, or films, typically one held annually in the same place.”7 This study therefore asks the following research questions: how has festival space been represented in today’s commercial space in China? What are the links between contemporary design for “urban festivity” and those found in history? To what extent do contemporary but traditionally styled commercial streets that serve as festive spaces both reveal and conceal the historic dimensions of festival events when constructed in new materials and technologies?

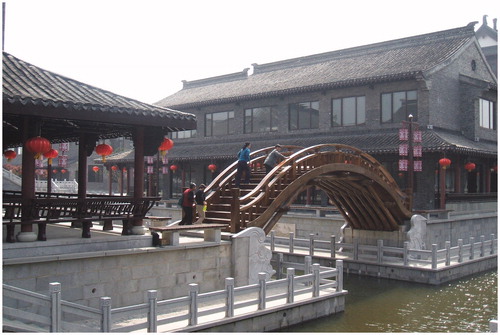

Water Street in Yancheng

Yancheng (Salt City) historically was a place in the Jiangnan area that was well known for the harvest of sea salt. The city is also famous as the home of Fan Zhongyan, governor of Salt City in the twelfth century, who is best remembered for his aphorism that the Confucian gentleman should be the “first to worry about the world's problems and last to enjoy its pleasures.”8

The Water Street project was identified as a leading initiative to demonstrate and celebrate cultural heritage in the city’s new town in 2008. One aim of the design was for new streets not only to provide a multifunctional place for food, shopping, entertainment and leisure, but also to create an ideal environment in the city by incorporating the adjacent Chan Chuan River within the new development. This combination was specifically intended to highlight that Salt City constitutes “a city with green water and as the capital of Wetland.”9 According to the brief, buildings in Water Street should be constructed in the traditional Hui style found in Huizhou, an adjacent town which is well known for its gray-tiled roofs and white walls. Due to restrictions on using timber in China, almost all of the traditional elements of buildings in Water Street are in fact made from reinforced concrete, despite being designed to resemble timber structures.10

In design terms, three themes were introduced and represented along three parallel axes that define Water Street. The first axis is called a “Centre of Human and Culture,” consisting of a traditional local governor’s office, yamen, fronted by a public square. In front of the yamen compound is Fan Zhongyan’s statue. His “public-spirited” style of Confucianism found full expression in the symmetrical layout of a series of courtyards in the yamen, an architectural language for Chinese palaces and traditional governor’s offices in China.11 Along the second axis are the “Plaza of Water in Paradise” and “Pavilion of Water and Cloud.” The auspicious names of these two places are built around the experience of happiness found in “a paradise on earth” (Runjian Tiantang). A leading Neo-Confucian scholar in the Song dynasty, Zhu Xi (1130–1200) who was highly regarded for his teaching on unorthodox Confucian principles in the region, believed that happiness consisted of the realization that there was a fundamental unity between the individual and the rest of the cosmos.12

Another building sited along the second axis is the Salt Ancestor Temple which celebrates five salt gods and goddesses. The associated rituals and legendary stories are related to certain festivals and mythical narratives that muted the religiosity of the temple. In contrast to the orthodox Confucian principles of li (courtesy and morality in order to discipline desire), these legends associated with the temple-advocated qing (romantic love or feelings), including a love story relating to the salt goddess. Opponents of the elevation of li to the status of an ontological truth in the Ming dynasty claimed that the so-called divine principle of li was simply a figment of the human mind.13 One of the leading characters that advocated qing was Feng Menglong, a vernacular writer and poet of the late Ming dynasty who was born in Suzhou. He failed to pass the civil service examinations, but devoted himself to collecting and editing vernacular plays and folk songs. Feng helped to raise the position of vernacular fiction and drama to that of high art.14

Along the third axis is a winehouse and a restaurant along the Yi Water and Theatre on Water (), which together signify happiness in leisurely life. Haiyan Lee’s study of the feelings and emotions expressed in Chinese novels from the nineteenth century identified significant changes that find resonance in these architectural elements. Traditional orthodox Confucian thought encompasses a range of values and experiences that was not in favor of expressing outward individual emotions.15 Lee argues that changes were brought by the May Fourth Movement in 1919 when intellectuals became enthusiastically in favor of understanding emotion and other universalizing norms of enlightenment humanism and nationalism. Later in the socialist era after 1949, there was an attempt to “resolve the basic conflict of modernity between the heroic and the everyday as well as to address the paradoxical status of emotion in the modern episteme.”16 John Fitzgerald also points out that a new idea of a self-conscious individuality took place in the “literary revolution” of modern China, intertwined with the notions of the awakening of a national self-identity.17

Whatever questions or criticisms can be raised about the superficial nature of reproducing timber construction in concrete, the three themes that inform Water Street demonstrably seek to inherit a deep tradition of social and literary change that are embedded in the culture of the commercial built environment. The design of the spatial arrangements of streets consciously inherited ideas from many traditional paintings that represented cities during festive events. As Wang Zhenhua has observed, traditional paintings depicted festivals in Chinese cities’ throughout history in different ways.18 For example, Shang Yuan Deng Cai Tu (“Picture of Colored Lanterns in Lantern Festival”) illustrates the activities during the Lantern Festival: a colored lantern parade, fireworks and acrobatic performances in the theater and on the streets. Spectators are shown watching these spectacles along the streets and from first-floor windows overlooking these public thoroughfares. They enjoy examining paintings, gazing at flowers and fish in the open markets and in shops. Both performers and spectators mingle and form crowds. In such representations, commercial activities and festival events are intertwined in those moments, a feature of public life that has long pervaded Chinese culture. Wang argues that paintings like the one mentioned represent “unofficial entertainment activities” in the city; these activities are very different from those presented in the more famous painting Ching Ming Shang He Tu (“Along the River During the Qingming Festival”), originally produced in the Song dynasty, which illustrates how people were busy in their working lives in a more officially ordered fashion with little commercial activity evident.19

By constructing traditional-style streets, a canal, temple, theaters and restaurants, the traditional Chinese-style buildings and associated urban spaces become vehicles to carry the memories of traditional festivals because they are very different from the contemporary urban spaces in the city. In attempting, however, to imitate traditional timber construction using concrete, for the purpose of preserving forests, the whole commercial enterprise reveals an obvious paradox; by arguing for the rebuilding of historical streets there is a danger that the buildings in the end appear less convincingly historical, giving less value to material culture and to issues of authenticity, a topic that is beyond the scope of this current study. In spite of these reservations, the construction teams and craftsmen have innovatively sought to reproduce traditional forms that are required by the design, by exploring new ways of using contemporary materials and technologies.

In practice, there was little guidance or record to follow in terms of how to use contemporary materials and technologies to construct traditional-style buildings that can represent the three themes mentioned. In order to ensure the details of windows, doors, tiles, bridges and city gate were built in “authentic” traditional forms, experienced carpenters, tile makers and other traditional craftsmen in the area were mobilized to work for the project during its construction period. This reminds us of what Pierre Ryckmans appreciated in the views expressed by Victor Segalen (1878–1919), who observed how the Chinese built obsolescence into their buildings:

[E]ternity should not inhabit the building, it should inhabit the builder. The transient nature of the structure is like an offering to the voracity of time; for the price of such sacrifices, the constructors ensure the everlastingness of their spiritual designs.20

In our interviews with visitors to Water Street, there were two different kinds of expectations for people’s visits.21 Around seventy percent of visitors were there because Water Street not only provided visual images of a local historical city, but also allowed them to have bodily experience in the place: watching local performances, walking along with actors dressed as imperial officers “working” in yamen or dressed as fishermen paddling boats in canals, tasting local food, dressed in traditional clothes and taking photographs. About thirty percent of visitors were residents in the city who came to the street to relax because of its pleasant environment. The generous open public space, well-maintained green areas and water bodies eventually became “real life,” inseparable from their daily activities. Only six percent of all those interviewed pointed out that the traditional styles were fake. It also became apparent that many visitors did not know the specific local history, but overall the connected memory of the traditional Jiangnan urban landscape was recognized. As Wang suggested, these traditionally styled festival streets transformed urban spaces into special landscapes and sceneries, bearing a similar function to their authentic historical counterparts. This was a public space for everyone to participate in, just as popular arts provided in the marketplace for ordinary people have always done.22

Paradoxically, these traditional forms of buildings in Water Street newly created by contemporary builders are now associated with the historical festival contents, rather than with the materials and technologies of construction. Carrying meanings associated with traditional festivals rather than contemporary materials and their context is the role of the traditional-style commercial streets in contemporary Chinese societies.

Old Street in Kunming

If Water Street typifies festival space as a self-consciously designed enterprise in Jiangnan, Wenming Street in Kunming constitutes a genuine historic street comprising traditional courtyard houses built in the Ming and Qing dynasties.23 Kunming is a city located on the southwest borderland of China. Different from the Jiangnan area, Yunnan province was famous for its twenty-six ethnic groups living in the region with very different cultures, although Confucian teaching has influenced the region since the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368).24

Kunming city, as the capital of the province, went through rapid urbanization after economic reforms in the 1980s. Many traditional streets were demolished to give way to wider roads and high-rise buildings. As the last surviving traditional street in the city, Wenming Street was identified as a protected area for traditional buildings by the city planning department in the 1980s. Unlike Water Street, with its inherited themes from Confucian teaching combined with commercial space, the ambition in this case was to renovate and restore old buildings in their original historic situations following the principles of “renovate old building as the original historic form and structure.” Due to changes in planning policy, it was eventually decided that the whole of Wenming Street should be protected to retain the context of a traditional commercial district.25 Developers were brought in to provide funding to refurbish traditional timber buildings on one side of the street and to develop the other side as a commercial street with mixed building styles and architectural elements.

Apart from a number of courtyard houses that were restored as listed buildings, the rest of the development has adopted a mixture of old and new architectural design language (). For example, window shutters on buildings on the street are generally made of timber, establishing a link with traditional materials in listed buildings. However, rather than adopting traditional patterns, the new shutters are made into vertical lines, creating a contemporary rather than a traditional expression. The new parts of the street with concrete paving are also designed with changing views when visitors move through open and closed public spaces, similar to traditional streets. The organizers and management for the street did not assign the events on the street to certain themes. A variety of shops selling fashion clothing, traditional crafts, fast food and traditional food sit side by side, expressing full hedonism.

Figure 2 Traditional and Modern-Style Buildings on Old Street in Kunming. Photograph by Yun Gao, 2013.

In order to attract investments for the project to protect listed buildings and their surrounding environment on one side of the street, the regulations and building codes that applied to the opposite side of the street were relaxed, to allow contemporary design with new materials and technologies. Consequently, the street is defined as a spatial juxtaposition between restored historical fabric on one side and contemporary commercial developments on the other. As a result, there is no consistent architectural expression of the street. Architecture is defined as a duality of stylistic and material relationships and their associated modes of craftsmanship; including the connections between spaces, together with functions and the movement of pedestrians. In Kunming, Wenming Street is a popular place for both visitors to the city and local citizens, primarily because of its location in the city center.

Conclusion

In this study, we have examined how contemporary Chinese attitudes toward the locations of traditional festive events in historic mercantile streets actively draw upon their commercial potential, and at the same time generate a desire to revive or preserve a heritage of social participation. This study explores themes relating to these intersections between building and festive occasion through an examination of two traditionally designed commercial streets in China. Architecture in these two cases presents in different ways a foregrounding of festivals, in which participants are reminded of previous events.

The Water Street development in Salt City was accompanied by “reenactments” of festive rituals, visible along both the public pathways and the waterways. “Reconstruction” of traditional commercial streets serves as the backdrop for conscious reinventions (or simulations) of temporal acts relating to procession and movement. Contemporary materials and technologies are used to mimic traditional forms and materials, which invariably raises important questions about authenticity and meaning. Rather than separating the architectural language to express tectonic composition and technology from the expression for principles in life and emotions in literary language, traditional building forms were used to pursue transferable expressions for political, spiritual and emotional meanings embedded in architectural composition. In this case, we argue that questions concerning the absence of “authentic” material culture, where concrete is used as a viable and convincing substitute for age-old crafts in timber construction, are partly mitigated by the semblance of re-authenticating the setting through human acts and gestures.

In Old Street in Kunming, however, identity of place is graded in the new and old buildings, as well as the commercial shops and commodities. Therefore, a mixture of contemporary and historical architectural languages presents another kind of built environment for festivals that consciously expresses stylistic divisions, which the festival event itself serves to reconcile. In both cases, however, we can see how architecture presents itself as an effective camouflaging and mediating device to both reveal and conceal the historic dimensions of festival events, even when these are no longer actively performed.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yun Gao

Yun Gao is a qualified architect and senior lecturer at the School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Huddersfield, UK. She has previously published Architecture of Dai Nationality in Yunnan (Beijing University Press, 2003) and Being There (University of Huddersfield Press, 2010), and is currently is completing a book with Nicholas Temple entitled The Temporality of Building: European and Chinese Perspectives on Architecture and Heritage (Routledge, 2019).

Nicholas Temple

Nicholas Temple is a qualified architect and professor of architecture at the University of Huddersfield, UK. His publications include Disclosing Horizons: Architecture, Perspective and Redemptive Space (Routledge, 2007), and the coedited volumes Architecture and Justice: Judicial Meanings in the Public Realm (Ashgate, 2013) and Bishop Robert Grosseteste and Lincoln Cathedral: Tracing Relationships between Medieval Concepts of Order and Built Form (Ashgate, 2014).

Yan Li

Yan Li is a doctoral student at the University of Huddersfield, UK who studies craftsmanship in the contemporary traditional-style commercial street in China.

Notes

1 Yue Meng, Shanghai and the Edges of Empires (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 65.

2 Christian de Pee, “Purchase on Power: Imperial Space and Commercial Space in Song-Dynasty Kaifeng, 960–1127,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53 (2010): 35.

3 Xiyuan Chen, “Zhongguo ye wei mian ming qing shiqi de yuanxiao, ye jin yu kuanghuan” [Sleepless Chinese Nights: Yuanxiao Festival, Night Ban and Carnival the Ming and Qing Dynasties], Zhongyang yan jiu yuan lishi yuyan suo jikan [Research Paper Collections of National Research Institute of History and Languages] 72 (2004): 44.

4 Meng, Shanghai and the Edges of Empires.

5 Benjamin A. Elman, Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

6 Zhenhua Wang, “Guoyan fanhua, wan ming chengshi tu. Chengshi guan yu wenhua xiaofei de yanjiu” [Flourishing Over the Clouds: A Study on Urban Paintings, Urban Views and Cultural Consumption in the Late Qing Dynasty], in Zhongguo de chengshi shenghuo [Chinese Urban Life], ed. Li Xiaoti (Beijing: Beijing University Press 2013), 119–160.

7 The publishing committee of editing and translating for the Oxford English–Chinese Dictionary, The New Oxford English–Chinese Dictionary (Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2007), 636.

8 The sentences were written by Fan Zhongyan in 1046 in his “Fu Notes About Yueyang Tower” (Yueyang Lou Ji). The article was widely quoted and published in various books. One of them can be found in Fan Zhongyan, “Yueyang Lou Ji” [Fu Notes About Yueyang Tower], Zhongguo gudai wenxue zuopin xuan [Chinese Ancient Literary Works] (Beijing: People’s Literature Press, 2002), 21.

9 Words from the brief of the Water Street project that were communicated to authors in an interview with the Project Manager Mr Li on November 2, 2017.

10 In 1998, in an effort to promote forest management activities to prevent forest destruction and further deterioration, timber harvests from China’s natural forests were reduced from 32 million m3 in 1997 to 29 million m3 in 1998, and then to 23 million m3 in 1999. See Wenhua Li, “Degradation and Restoration of Forest Ecosystems in China,” Forest Ecology and Management 201 (2004): 8.

11 Peter Blundell Jones, “The Architecture and Operation of the Imperial Chinese Yamen,” in Architecture and Justice – Judicial Meanings in the Public Realm, ed. Jonathan Simon, Nicholas Temple and Renée Tobe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), 131-150.

12 Liwen Zhang, “Zhu Xi’s Metaphysics,” in Returning to Zhu Xi: Emerging Patterns within the Supreme Polarity (New York: State University of New York Press, 2015), 15-50.

13 Ruchang Zhou, “Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber,” in Asian Thought and Culture (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2009), 62.

14 Ibid., 137.

15 Haiyan Lee, Revolution of the Heart: A Genealogy of Love in China, 1900–1950 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), 9.

16 Ibid., 15.

17 John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press 1994), 92.

18 Wang, “Guoyan fanhua” [Flourishing over the Clouds], 29–81.

19 Ibid., 49.

20 Pierre Ryckmans, “The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past,” in China Heritage Quarterly, China Heritage Project (The Australian National University, 2008). Available online: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=014_chineseattitude.inc&issue=014 (accessed March 15, 2017).

21 Yan Li carried out interviews with more than 200 outside visitors and local residents who visited Water Street from 2015 to 2016.

22 Data from Li Yan's interview with visitors to Water Street between 2015 and 2016.

23 Yun Gao and Nicholas Temple, “The Value and Meaning of Temporality and its Relationship to Identity in Kunming City, China,” in City and Society: The Care of the Self, ed. Gregory Bracken (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018), 193-218.

24 Benshu Xie, Jiang Li and Yingshen Ma, Kunming Chengshi Shi [A History of Kunming City] (Kunming: Yunnan University Press, 2009).

25 Xuemei Gao, “Written for 30 Years of Friendship and Cooperation between Kunming and Zurich,” in Planning Works as the Results of the Cooperation between Kunming and Zurich as Sister Cities (Kunming: Yunnan Publisher and Yunnan Science Publisher, 2012), 136–137.

References

- Blundell Jones, Peter. 2013. “The Architecture and Operation of the Imperial Chinese Yamen.” In Architecture and Justice – Judicial Meanings in the Public Realm, edited by Jonathan Simon, Nicholas Temple and Renée Tobe. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Chen, Xiyuan. 2004. “Zhongguo ye wei mian – ming qing shiqi de yuanxiao, ye jin yu kuanghuan” [Sleepless Chinese Nights: Yuanxiao Festival, Night Ban and Carnival in the Ming and Qing Dynasties], Zhongyang yan jiu yuan lishi yuyan suo jikan [Research Paper Collections of National Research Institute of History and Languages], 72, no. 2: 44.

- Elman, Benjamin A. 2013. Civil Examinations and Meritocracy in Late Imperial China. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press.

- Fan, Zhongyan. 2002. “Yueyanglou ji” [Notes about Yueyang Tower]. In Zhongguo gudai wenxue zuopin xuan [Chinese Ancient Literary Works], edited by Ge Xiaoyin, 21. Beijing: People’s Literature Press.

- Fitzgerald, John. 1994. Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gao, Xuemei. 2012. “Written for 30 years of Friendship and Cooperation between Kunming and Zurich.” In Planning Works as the Results of the Cooperation between Kunming and Zurich as Sister Cities, edited by Kunming and Zurich Friendship Office, 136–137. Kunming, Yunnan: Publisher and Yunnan Science Publisher.

- Gao, Yun, and Nicholas Temple. 2018. “The Value and Meaning of Temporality and Its Relationship to Identity in Kunming City, China.” In City and Society: The Care of the Self, edited by Gregory Bracken, 193–218. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Lee, Haiyan. 2007. Revolution of the Heart: A Genealogy of Love in China, 1900-1950. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Li, Wenhua. 2004. “Degradation and Restoration of Forest Ecosystems in China,” Forest Ecology and Management. 201: 8.

- Meng, Yue. 2006. Shanghai and the Edges of Empires. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

- The New Oxford English–Chinese Dictionary. 2007. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

- Pee, Christian de. 2010. “Purchase on Power: Imperial Space and Commercial Space in Song-Dynasty Kaifeng, 960-1127,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 53: 149–184.

- Ryckmans, Pierre. 2008. “The Chinese Attitude towards the Past,” China Heritage Quarterly, China Heritage Project, The Australian National University, 14. Available online: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=014_chineseattitude.inc&issue=014

- Wang, Zenhua. 2013. “Guoyan fanhua, wan ming chengshi tu. Chengshi guan yu wenhua xiaofei de yanjiu” [Flourishing Over the Clouds: A Study on Urban Paintings, Urban Views and Cultural Consumption in the Late Qing Dynasty]. In Zhongguo de chengshi shenghuo [Chinese Urban Life], edited by Li Xiaodi, 119–160. Beijing: Beijing University Press.

- Zhang, Liwen. 2015. “Zhu Xi’s Metaphysics.” In Returning to Zhu Xi: Emerging Patterns within the Supreme Polarity, eds. David Jones and Jinli He. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Zhou, Ruchang. 2009. Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Xie, Benshu, Jiang Li and Yingshen Ma. 2009. Kunming Chengshi Shi [A History of Kunming City Kunming], Kunming: Yunnan University Press.