Abstract

This article develops a theory of the multitude for architecture. It is a close-reading of political theorist Paolo Virno’s concept of the multitude and its associated categories of language, repetition and what Virno calls “real abstraction.” The article transposes those categories to the thought of Aldo Rossi on typology, the city as a text and the analogical city. The aim is to explore the conditions of possibility for a renewed critical project for architecture and to articulate architecture’s capacity for framing a collective political subject. The key questions addressed are therefore how does Virno’s grammar of the multitude translate into an architectural grammar for the city; and how can architecture frame a collective political subject?

Introduction

At a time when collective experience is everywhere threatened by a world in the grips of capitalist idealization of the individual and the cult of personality, when there is ever less space for critical narratives and when architecture seems to have forgotten its capacity to frame a political subject, the need for a critical project remains urgent. Critique was a hallmark of the 1960s and 1970s, a period that Michael Hays called the “age of discourse” when architecture was framed as a language in which the discipline’s boundaries and conditions were theorized as a logical grammar with syntax and structure.Footnote1 The key figures engaged in political and philosophical reflections on architecture’s position in society and history.Footnote2 Buildings, urban plans, cities, drawings, images, architectural projects and their contexts were understood as “texts” linked within a discursive chain connected to thought and ideology made “readable” by critique. If architecture could be read then it could also be reread and therefore rewritten toward alternative possibilities, which consciously or unconsciously, brought a sense of agency to the architect and architecture’s place in collective life.

Such a sense of agency and strategy of critique has been lost at least since the 1990s when understanding architecture as a language has been largely rejected by architects and theorists. Architects have uncritically produced buildings characterized by multifarious material and formal expression, from institutional to residential typologies, emphasizing architecture as individual object at the expense of a coherent and dignified collective urban realm.Footnote3 Architectural production has tended to be theorized in terms of affect and atmosphere, justified in terms of technical instrumentality aligned to “networked intelligence” and produced for the spectacle of global capitalist development.Footnote4 As has been remarked by Nadir Lahiji, architecture’s abandonment of a critical project since the 1990s is synonymous with the disavowal of the political in architecture and consequently we have forgotten the legacy of radical critical lessons.Footnote5

In recent years, the language question has been raised again, in particular within the context of political thought. Theorists have developed readings of the linguistic character of contemporary subjectivity, work and labor relations. Thinkers such as Christian Marazzi, Paolo Virno, Maurizzio Lazzarato and Antonio Negri have analyzed the centrality of language within society and argued that language is not only individual and communicative but a “creative force” (Marazzi), which shapes society’s “forms of life” (Virno) to configure a new collective political subject – what Negri calls a “new reality” – termed the “multitude.”Footnote6 It is possible to speculate that the categories and critical tools developed by political theorists can productively address the relationship between architecture and language, the political and the critical, and the agency of the architect toward a new, collective and critical project for architecture and the city. The key questions addressed in what follows are: how does a grammar of the multitude, to borrow the title of Virno’s book, translate into an architectural grammar for the city; and how can architecture frame a collective political subject? Such questions are also questions of collective will and a broader societal shift toward a collective form against the long standing capitalist affirmation of individuality. The article is therefore necessarily partial and understood as a contribution to a larger project.Footnote7

This article is divided in two. In the first part I reflect specifically on Paolo Virno’s essay “Three Remarks Regarding the Multitude’s Subjectivity and Its Aesthetic Component” and more broadly on a selection of Virno’s key texts to situate the notion of multitude. In the “Three Remarks” essay Virno sets out what he calls “three political and aesthetic tasks for critical theory” as “a theory of the multitude,” which in summary relate to language, repetition and what Virno calls “real abstraction.”Footnote8 If there is an esthetic theory of the multitude as Virno argues, I argue there is an architectural theory of the multitude. In the second part of this article I transpose the political categories put forward by Virno concerning language, repetition, real abstraction and the political-linguistic subject of multitude, onto architecture. Those categories are the framework through which I reread concepts of typology, the city as a text and analogical cities in the ideas, drawings and writings of Aldo Rossi. Rossi’s thought and projects were at the center of architecture’s linguistic turn in the 60s and 70s and his work contains unfinished lessons. In the text that follows I elaborate the connections between Virno’s and Rossi’s thought on the relationship between individual and collective life focused on the concept of the city. In dialogue with the text is a series of drawings and montages, which reconfigure Rossi’s thought in visual terms and articulate a possible architectural grammar of the multitude. I conclude with a reflection on the renewed potential for architecture’s critical project today toward an architectural theory of the multitude.

Multitude and the City

Over recent decades Paolo Virno has theorized a collective political subject, which he and others refer to as the multitude. The multitude signifies an ethos of common political and social existence. One of the key texts to develop a theory of the multitude is Virno’s A Grammar of the Multitude. Virno examines the relationship between language, subjectivity and the shift of political acts (speech, thought, plurality, acting together) to the sphere of production. He proposes a lexicon for elucidating and understanding the changed organization of life and work as they merge within advanced capitalism. Virno rethinks normative categories of political thought such as the people, nation, state, private, public, sovereignty; to categories of multitude, singularity, common places, life of the mind, social individual, general intellect, amongst others. With a so called grammar of the multitude arises a possible reorganization of collective life and class composition. Virno writes: “Multitude indicates a plurality which persists as such in the public scene, in collective action, in the handling of communal affairs, without converging into a One, without evaporating within a centripetal form of motion.”Footnote9 The multitude does not converge into a “totalising unity” nor “dissolve into numerous individuals” but is instead characterized as many distinct individuals who collectively share the experience of living together and the faculty of language as a linguistic mode of being: “The unity which the multitude has behind itself is constituted by the ‘common places’ of the mind, by the linguistic-cognitive faculties common to the species, by the general intellect.”Footnote10 What Virno calls the “singularity” of the multitude, “reaches its highest level in common action, in the plurality of voices and, finally, in the common sphere.”Footnote11

Virno’s definition of the multitude draws in part on a reading of Hannah Arendt’s notion of human plurality and being in “the presence of others” as a precondition of political life.Footnote12 At the same time Virno develops his argument through a reading of Ferdinand de Saussure’s notion of the relationality of language through which Virno argues for the “intrinsically political nature of language.”Footnote13 Virno finds in the multitude a term to describe the active, thinking, imagining, autonomous subject, a linguistic subject who, paraphrasing Arendt, is every single human being who has the faculty to speak, think and act together. In “Three Remarks Regarding the Multitude’s Subjectivity and Its Aesthetic Component” Virno turns specifically to the esthetic sphere and puts forward “three tasks” for an esthetic theory of the multitude.

First Virno analyses contemporary society and characterizes today’s condition as centered on language. At its broadest, language incorporates thought, memory, imagination, abstraction, creativity, speech, the capacity for social relations. Language is shared and intersubjective. Language provides a common basis for the patterning of everyday life. Language is the material of contemporary modes of production, from the “culture industry” to the “knowledge economy” and “cognitive capitalism.”Footnote14 Language condenses with the linguistic nature of the multitude and the social and intellectual forms of life of the metropolis as a commitment to living together. The metropolis is where Virno situates the multitude and he writes the following:

… it is the contemporary metropolis that is built on the model of language. The metropolis appears as a labyrinth of expressions, metaphors, proper names, and propositions, of tenses and moods of the verb…. The metropolis actually is a linguistic formation, an environment that is above all constituted by objectivised discourse, by preconstructed code, and by materialised grammar.

… In the post-Fordist metropolis, the material labour process can be described empirically as an ensemble of speech acts, as a sequence of assertions, as symbolic interaction. … Above all because the “raw material” of the labour process is knowledge, information, culture, and social relations.Footnote15

It is possible to say that the city is a linguistic form. Cities are structured by real and imaginary signs, a “materialised grammar” of digital, transport and social networks. Urban institutions such as the university to the call center produce knowledge, information, images, speech acts and new social relations. Unconscious and symbolic interactions are spatialized by “the flesh and the word” of the multitude who live and share the linguistic experience of the city. With the integration of language into the process of production as a dominant condition of the present, language is now what Virno calls “the terrain of conflict” and is materialized by the multitude in the city.

In the second part of his essay Virno considers the political possibilities and critical strategies under the conditions of the city “modelled on language.” He reconsiders Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in which Benjamin argues that technical reproducibility was an emancipatory practice that liberated the “cult value” (or “uniqueness”) of the artwork to destroy its “aura” through repetition by photography, film and montage as an everyday occurrence.Footnote16 For Benjamin reproducibility, or repetition, detaches a given artwork from its uniqueness: “By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence” so the artwork enters into common occurrence and collective life.Footnote17 For Benjamin, repetition was a critical strategy to reverse the terms of what is foregrounded and special, to background and common. Following Benjamin, Virno proposes the notion of repetition to absorb the shock of metropolitan life and capitalist exploitation and produces what Virno calls “uniqueness without aura.”Footnote18 Virno writes: “Repetition is the way to deal with the uncanny of primary experiences. Benjamin sees that repeating the same again and again constitutes a common, liberates the heart from fear, transforms the shocking experience to a custom.”Footnote19 While Benjamin saw the destruction of aura as a critical strategy to emancipate the mass subject, Virno partly reverses the concept and reclaims the significance of “uniqueness” but transposes it to the collective subject of the multitude. Virno writes: “I propose calling the combination of ‘social individuals’ the multitude. We could say … that the radical transformation of the present state of things consists in bestowing maximum prominence and maximum value on the existence of every single member of the species.”Footnote20 In other words, the uniqueness of every person that makes up the multitude. “Uniqueness without aura” therefore stands on one hand for the agency of the individual without the capitalist idealization of individuality and on the other hand as a critical strategy of repetition, which I argue is a basis for a logical grammatical architecture.Footnote21

In the third part Virno focuses on what he has called “real abstraction” and “second order sensualism.”Footnote22 While first order sensations are surface feelings such as an aching tooth or the coldness of snow, second order sensations concern the final material embodiment of pure abstract thought. Virno writes that second order sensations require strong and complex thought rooted in linguistic knowledge and intersubjective experience. In the examples Virno uses in his “Three Remarks” there is a syntactical and associative movement between abstraction to sensation and vision, individual to collective and from pure thought to the real materiality of the body and life. Virno writes:

I find an “a” very bright, whereas my perception of an “o” is dark, sombre. … such sensorial impressions presuppose a certain familiarity with quite abstract objects – as vowels are. Likewise, when I see melancholia or embarrassment in the face of a beloved person, I see immediately something that I wouldn’t have been able to notice without knowing the meaning of the concepts of melancholia or embarrassment. Another example: looking at the outline of a triangle, there will be people who will see an eye whereas others will see an arrow; but both perceptions depend on knowledge of the geometric figure called “triangle.”Footnote23

The “three tasks” put forward by Virno can be summarized in the following framework, which reformulates them for an architectural context:

Language: to translate the productive power of language into political and esthetic (architectural) power as a language of spatial-formal, syntactical-associative and typological elements;

Repetition: to realize the notion of repetition as singular experience (“uniqueness without aura”) and that repetition is a critical strategy for a logical grammatical architecture of the city;

Real abstraction: to valorize the corporeal character of the multitude, taking advantage of the pure thought, abstraction and imagination embodied by the multitude as agency and critical authorship.

The Analogical City as Locus of the Multitude

Reflecting on the recent history of architectural and urban thought it is possible to identify Aldo Rossi’s thought and projects as exemplary for helping elucidate the framework delineated in the last section. Aldo Rossi’s work was at the center of the linguistic structuralisation of architecture and the city beginning in the 1960s. In The Architecture of the City Rossi wrote: “The points specified by Ferdinand de Saussure for the development of linguistics can be translated into a program for the development of an urban science….”Footnote24 Rossi transposed that proposition to an understanding of the syntactical and associative structure of the city, and he defines categories to understand those relations: urban artifact, urban quarter, monument, permanence, collective memory, the type, the model. He described the city as an “historical text” (echoed by Virno in his notion of the “metropolis modeled on language”), which could be “read” by the principle of type.Footnote25

For Rossi, typology was on one hand an analytical framework to interpret the “formal and political individuation” of the city through its architectural types.Footnote26 Those types included the primary elements and urban artifacts of the city that repeat most across history – the monument, the street, the central plan, the grid – and which correlate to a grammar of the city. Rossi understood architectural types as embodying the collective memory of the city because types, as historically and politically produced, bound the architectural object to the world, the city and history, establishing a chain of relations through their formal and associative syntax. On the other hand the notion of type was a generative principle of the architectural imagination so that the history of the city, its architectural types, elements and urban structure became the material for transformation. Rossi’s theory of typology combined Quatremère de Quincy’s conceptual and associative notion of type as idea and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand’s syntactical definition of type as a combinatory method. While Quatremère de Quincy proposed type as “the idea of an element that must itself serve as a rule for the model…,” for Durand the typological elements of architecture were grids and axes that structured the overall architectural composition, with the rooms, walls and columns as elements to be combined and recombined from project to project.Footnote27

Those conceptual, associative and syntactical principles were given form and critiqued in Rossi’s drawings and urban studies of the 1960s and 1970s. Rossi’s studies always conveyed on one hand authorial intention and on the other a commitment to architecture as collective knowledge in which the city was a repository of shared experience and history, articulated by architectural typologies.Footnote28 In drawings and collages such as Composition No. 2 (1968), Composition No. 3 (1968) and Untitled (1972) Rossi developed a language of typologies and typological elements – plinths, piers, loggias, colonnades, stairs, giant order columns, square windows, flat or pedimented roofs – by means of a simple abstract and geometric formal language.Footnote29 Rossi’s drawings, and by association his buildings, develop a grammar of elements and a syntax for their combination.

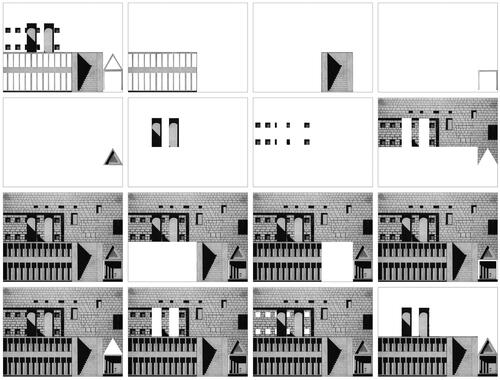

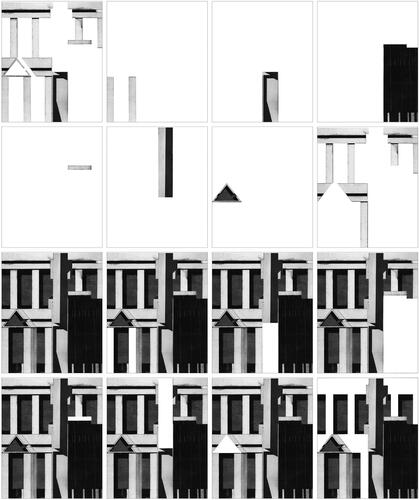

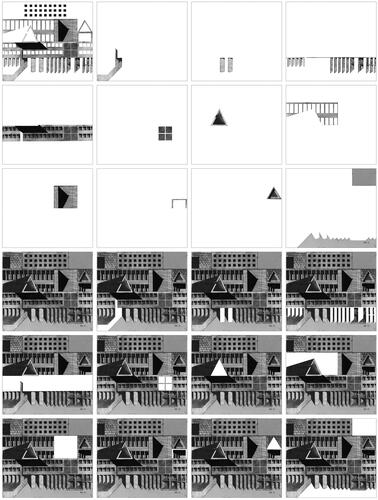

As part of the close-reading of Rossi’s thought on the typological, and hence the repetitive linguistic character of the city, I produced a series of analytical drawings (). What I call “close-drawing,” disarticulate Rossi’s drawings into their constituent elements organized by a formal grammar of repetition.Footnote30 The principle typological elements are defined and it is possible to identify operations including repetition, addition, subtraction, erasure, separation, combination, framing and scaling. Elements are repeated, combined and recombined with slight modifications from drawing to drawing, project to project and a language is constructed. Scaling procedures amplify or reduce particular elements. Repetition displaces and repositions elements into different drawings. Elements are added and multiplied to create assemblages or subtracted to distill singular elements. The perception that the city is an historical text constructed by syntax, grammar and by association, subjectivity and imagination, led Rossi to the idea of the analogical city.

Figure 1 Cameron McEwan, Disarticulation of typological elements No. 1, 2019. Montage. Base drawing: Aldo Rossi, Composition No. 2, 1968. Reproduced from: Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi: Drawings (Milan: Skira, 2008).

Figure 2 Cameron McEwan, Disarticulation of typological elements No. 2, 2019. Montage. Base drawing: Aldo Rossi, Composition No. 3, 1968. Reproduced from: Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi, Projects and Drawings, 1962–1979 (Florence; New York: Rizzoli, 1979).

Figure 3 Cameron McEwan, Disarticulation of typological elements No. 3, 2019. Montage. Base drawing: Aldo Rossi, Untitled, 1972. Reproduced from: Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi: Drawings (Milan: Skira, 2008).

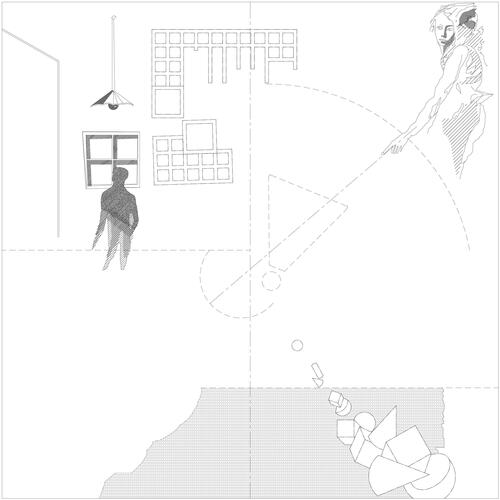

The analogical city signifies the idea that cities are analogues of collective thought and that each city is connected to one another in a discursive chain.Footnote31 The analogical city emphasized notions of subjectivity, imagination and therefore agency, which are key themes in Virno’s idea of multitude. Rossi’s collage project, Analogical City: Panel (1976), developed in collaboration with Eraldo Consolascio, Bruno Reichlin and Fabio Reinhart, compiles plans and other images with fragments of cities and territories, including: a Renaissance Ideal City, Nolli-esque urban fabric, a portion of Piranesi’s Campo Marzio, a lake, Alpine topography.Footnote32 Canonical projects by Palladio, Terragni, Le Corbusier and many others are positioned within the fabric of the analogical city. Rossi and his team insert their own prior projects into the city along with domestic and platonic objects. A dialogue across the history of architecture and the city is presented as a reflection on architecture through a displacement and repetition of cities, combinations of contexts and individual architectural projects composed in a square frame. At the edges of the frame are positioned the bust of David from Tanzio di Varallo’s painting and Rossi’s specter of a human figure ().

Figure 4 Cameron McEwan, A Grammar of the Analogical City, 2019. Analytical drawing of Aldo Rossi et al., Analogical City: Panel, 1976.

The figure in the Analogical City: Panel represents the multitude. Neither appearing as fully materialized nor totally dissolved into the city, the figure is incomplete and signifies a process of subject formation. The incompleteness of the individual subject is in dialogue with the collective life of the city, which itself is always incomplete. The multitude is bound together in the space of this mutual incompleteness, in the space between thought and the world.Footnote33 The analogical city, to paraphrase Rossi, is the locus of the multitude.

Conclusion: Toward an Architectural Theory of the Multitude

This article put forward a framework for an architectural theory of the multitude through which a critical project for architecture and the city might be structured.Footnote34 It transposed Paolo Virno’s remarks on an esthetics of the multitude and the categories of language, repetition and real abstraction to the thought and projects of Aldo Rossi on notions of type, the city as a text and analogical cities. Rossi’s architecture is interpreted as an example of a critical project that helps elucidate an architectural theory of the multitude.Footnote35

To theorize an architecture of the multitude is to address architecture and the city as the manifestation of collective life and articulate a material grammar of the city. Mario Gandelsonas once wrote: “the constitutive rules of the [architectural] object, implies at the same time its subject.”Footnote36 Gandelsonas argued that only when architecture was developed as a discourse with identifiable elements in formal relationship with rules governing those relations (in other words a grammar), then a subject (we can say the collective subject of the multitude) takes on what Gandelsonas calls “clear configuration.” Rossi argued that the city was a “historical text” with a grammar of architectural types in formal relationship that manifested collective memory. The city interpreted in such a way is in Virno’s terms, a real abstraction. Paraphrasing Gandelsonas and with Virno’s “metropolis modeled on language” and Rossi close in mind, it is more necessary than ever for the architecture of the city to be understood as a coherent grammar to structure the city, frame and give direction to the multitude as a collective political subject. We need to reclaim architecture as a critical project. The challenge is twofold. Architecture needs to operate simultaneously as a grammatical formalization of the city and its collective subject, and thereby as a political and philosophical critique of the capitalist system.

Acknowledgements

I thank Lorens Holm for his generous critique of earlier versions of this paper, the peer reviewers for their insightful comments and UCLan’s research office which funded my contribution to the Architecture and Collective Life conference at Dundee where I first delivered this article as a talk.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cameron McEwan

Cameron McEwan is an educator and researcher at UCLan Institute of Architecture where he leads the Typological Project studio and Critical Narratives research group. Cameron is a trustee of the AE Foundation and holds a PhD in History and Theory of Architecture from the Geddes Institute University of Dundee. He researches the relationship between architecture, representation and subjectivity to engage the city as a critical project. Cameron’s work is published in arq, Drawing On, JAE, LoSquaderno, MONU, Outsiders (2014 Venice Biennale) and elsewhere. With Samuel Penn he edited Accounts (Pelinu, 2019). Cameron is writing a book entitled Analogical City.

Notes

1. K. Michael Hays, Architecture’s Desire: Reading the Late Avant-Garde (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 3. Also refer Manfredo Tafuri, “L’Architecture Dans Le Boudoir: The Language of Criticism and the Criticism of Language,” [1974] in Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture 1973–1984, ed. K. Michael Hays, translated by Victor Caliandro (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 291–316; and Mario Gandelsonas, “From Structure to Subject: The Formation of an Architectural Language,” [1979] in Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture 1973–1984, ed. K. Michael Hays (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998).

2. Figures including: Peter Eisenman, Manfredo Tafuri, Alan Colquhoun, Kenneth Frampton, Bernard Tschumi, Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas in addition to Aldo Rossi, whose work is the subject of discussion here.

3. I have in mind some of the well-known projects of the 1990s by high profile architects including: Zaha Hadid’s Vitra Fire Station (1992), Herzog and de Meuron’s Basel Signal Box (1995), Peter Zumthor’s Therme Vals (1996), Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim (1997), Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin (1999), Greg Lynn’s Korean Presbyterian Church in New York (1999). This lineage extends today in buildings such as Reiser + Umemoto’s Kaohsiung Port Terminal (2017) and Heatherwick’s shopping centre at Coal Drops Yard (2018) but now also includes residential buildings such as Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park Avenue (2015) and BIG’s ARAhaus (2019).

4. Jeffrey Kipnis, “Toward a New Architecture” [1993], in A Question of Qualities: Essays in Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 287–320. Kipnis champions the architecture of what Nadir Lahiji later called “neobaroque.” Kipnis groups together Greg Lynn to Frank Gehry and draws on Gilles Deleuze’s notion of The Fold as a primary theoretical referent. For Kipnis a “new architecture” would be “smooth,” “alien to site conditions” and produce “expressionist architectural effects.” Also refer Michael Speaks, “After Theory,” Architectural Record 193, no. 6 (2005): 72–75. Today’s free-market urbanism is represented by the thought and projects of Patrik Schumacher. Refer his “The Historical Pertinence of Parametricism and the Prospect of a Free Market Urban Order,” in The Politics of Parametricism: Digital Technologies in Architecture, ed. Matthew Poole and Manuel Shvartzberg (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 19–44.

5. Nadir Lahiji, “Introduction: The Critical Project and the Post-Political Suspension of Politics,” in Architecture Against the Post-Political: Essays in Reclaiming the Critical Project, ed. Nadir Lahiji (London: Routledge, 2014), 1–7. Elsewhere Lahiji has argued for the rearticulation of critique in the architectural discipline to reactivate architecture’s emancipatory core. See Nadir Lahiji, An Architecture Manifesto: Critical Reason and Theories of a Failed Practice (London; New York: Routledge, 2019).

6. Maurizio Lazzarato, Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity, trans. Joshua David Jordan (Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e); MIT Press, 2014); Christian Marazzi, Capital and Language: From the New Economy to the War Economy, trans. Gregory Conti (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2008); Antonio Negri, The Porcelain Workshop: For a New Grammar of Politics, trans. Noura Wedell (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2008); Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, trans. Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2004). The bibliography of these theorists is wide so I select only the most relevant to the present discussion. Concepts related to the multitude such as precarity, immaterial labour, the common and biopolitics are compelling areas of thought and require more detailed discussion than the scope of this article allows.

7. Chantal Mouffe, Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically (London: Verso, 2013), 99. Mouffe argues “a radical democratic politics calls for the articulation of different levels of struggle so as to create a chain of equivalence among them.” Architectural discourse is one level of struggle amongst others. Also refer Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics [1985] (London: Verso, 2014), 113–120. Laclau and Mouffe argue the “chain of equivalence” creates a commonality between different subjects, disciplines, practices and worldviews within a “discursive space” toward the construction of an alternative collective order.

8. Paolo Virno, “Three Remarks Regarding the Multitude’s Subjectivity and Its Aesthetic Component,” in Under Pressure: Pictures, Subjects, and the New Spirit of Capitalism, ed. Daniel Birnbaum and Isabelle Graw (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2008), 44.

9. Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude, 21, 76.

10. Ibid., 42.

11. Paolo Virno, When the Word Becomes Flesh: Language and Human Nature [2003], trans. Giuseppina Mecchia (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2015), 234.

12. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition [1958] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 7.

13. Virno, When the Word Becomes Flesh, 41. Also see Paolo Virno, An Essay on Negation: For a Linguistic Anthropology [2013], trans. Lorenzo Chiesa (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2018).

14. Gerald Raunig, Factories of Knowledge Industries of Creativity, trans. Aileen Derieg (Los Angeles, CA; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 17–18. Raunig analyses these categories and notes the conjunction of contradictory keywords that describe this situation: “Knowledge economy, knowledge age, knowledge-based economy, knowledge management, cognitive capitalism – these terms for the current social situation speak volumes. Knowledge becomes commodity, which is manufactured, fabricated and traded like material commodities.”

15. Virno, “Three Remarks Regarding the Multitude’s Subjectivity and Its Aesthetic Component,” 33–35.

16. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” [1936], in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (London: Fontana Press, 1992), 211–44.

17. Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” 222. When Benjamin argues that reproducibility produces plurality, which coincides with the mass subject of the twentieth-century metropolis, there is a resonance in Virno’s notion of multitude.

18. Virno, “Three Remarks…,” 45.

19. Ibid., 37. Also refer A Grammar of the Multitude, 40. Virno writes: “The publicness of the mind, the conspicuousness of ‘common places’, the general intellect – these are manifested as forms of the reassuring nature of repetition.” In When the Word Becomes Flesh, (p. 99) Virno puts repetition in dialogue with crisis: “From now on, ‘repetition’ will no longer mean a general recursive occurrence, but specifically the overcoming of a crisis.”

20. Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude, 80.

21. This argument is connected to repetition as critical authorship in the sense of what Michael Hays called the resistant authorship of critical architecture: “Repetition thus demonstrates how architecture can resist, rather than reflect, an external cultural reality. In this way authorship achieves a resistant authority … alternative to the dominant culture.” Refer K. Michael Hays, “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Form,” Perspecta 21 (1984): 14–29 (15). For reasons of space I cannot elaborate on this aspect of the argument.

22. Virno discusses real abstraction in A Grammar of the Multitude, 64. He writes: “A thought becoming a thing: here is what a real abstraction is.” In When the Word becomes Flesh Virno discusses real abstraction in the sections “Second-degree Sensualism” and “In Praise of Reification.” In his “Three Remarks…” essay, the terms second-degree and second-order sensualism, reification, and real abstraction are interchanged but focus on real abstraction as a collective thought physiologically embodied by the multitude. Also refer Alberto Toscano, “The Open Secret of Real Abstraction,” Rethinking Marxism 20, no. 2 (2008): 273–87.

23. Virno, “Three Remarks…,” 40–41. Also refer Roberto Esposito, Living Thought: The Origins and Actuality of Italian Philosophy [2010], trans. Zakiya Hanafi (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), 25. Esposito writes: “…what is at stake in political conflict is life itself, understood as that set of impulses, desires, and needs that run through the body of individuals and populations in a form that is irreducible to the distinction between res cogitans and res extensa, reason and force, or proper and common.”

24. Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City [1966], trans. by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982), 23.

25. Rossi, The Architecture of the City, 128.

26. Ibid., 88.

27. The quote on type as idea is from Quatremère, quoted by Rossi, The Architecture of the City, 40. Also refer Quatremère de Quincy, Quatremère De Quincy’s Historical Dictionary of Architecture: The True, the Fictive and the Real [1832], trans. Samir Younes (London: Papadakis Publisher, 2000), 254. For Durand refer Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, Précis of the Lectures on Architecture: With Graphic Portions of the Lectures on Architecture [1802–1805], trans. David Britt (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2000); Sergio Villari, J.N.L.Durand 1760–1834: Art and Science of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1990).

28. In “Architecture for Museums” Rossi notes the correspondence between the authorial and subjective decision made in project thinking and the political moment in architecture. See Aldo Rossi, “Architecture for Museums” [1966], in Aldo Rossi: Selected Writings and Projects, ed. by John O’Regan, trans. by Luigi Beltrandi (London: Architectural Design, 1983), 14–25.

29. On Rossi’s drawings see in particular: Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi in America: 1976–1979, ed. Peter Eisenman (IAUS New York: MIT Press, 1979); Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi, Projects and Drawings, 1962–1979, ed. Francesco Moschini (Florence; New York: Rizzoli, 1979); Aldo Rossi, Aldo Rossi: Drawings and Paintings, ed. Morris Adjmi and Giovanni Bertolotto (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1993).

30. I employ an expanded notion of drawing (close-drawing) where architectural drawing, montage, de-montage and diagram are used, often in combination, as analytical and interpretive tools to generate thought.

31. Rossi, The Architecture of the City, 134. Rossi wrote: “The memory of the city … coincides with the development of thought, and imagination becomes history and experience.”

32. Aldo Rossi, “La Città Analoga: Tavola / The Analogous City: Panel,” Lotus International 13 (1976): 4–9. Also refer Dario Rodighiero, “The Analogous City, The Map,” 2015, http://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/209326.

33. Virno, When the Word Becomes Flesh, 230. Virno writes: “The ethico-political concept of multitude is rooted both in the principle of individuation and in its constitutive incompleteness.” This idea could be further theorised in relation to Virno’s use of the term “oscillation” as a critical operation at key moments in When the Word Becomes Flesh and A Grammar of the Multitude. For reasons of space I cannot elaborate further.

34. The critical project necessarily draws on the lineage of critical theory beginning with Benjamin and Adorno through to Frankfurt School theorists and extending from Kant, Marx then Freud. For a recent reflection on critical theory see Martin Jay, Reason after Its Eclipse: On Late Critical Theory (Madison, WI; London: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2016). For recent architectural critical theory refer Nadir Lahiji, Adventures with the Theory of the Baroque and French Philosophy (London: Bloomsbury, 2016); Lahiji, An Architecture Manifesto.

35. There are other architects whose ideas, projects and writings form a broader genealogy of an architectural theory of the multitude. The partnership Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas is one example. They frequently reference Rossi, and Gandelsonas has written of his aim to “radicalize” Rossi’s “lessons.” See in particular Mario Gandelsonas, X-Urbanism: Architecture and the American City (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).

36. Gandelsonas, “From Structure to Subject,” 213.

References

- Arendt, Hannah. 1989. The Human Condition [1958]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1992. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” [1936]. In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, 211–44. London: Fontana Press.

- Durand, Jean-Nicolas-Louis. 2000. Précis of the Lectures on Architecture: With Graphic Portions of the Lectures on Architecture [1802–1805], translated by David Britt. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute.

- Esposito, Roberto. 2012. Living Thought: The Origins and Actuality of Italian Philosophy [2010], translated by Zakiya Hanafi. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gandelsonas, Mario. 1998. “From Structure to Subject: The Formation of an Architectural Language” [1979]. In Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture 1973–984, edited by K. Michael Hays, 200–223. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Gandelsonas, Mario. 1999. X-Urbanism: Architecture and the American City. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Hays, K. Michael. 1984. “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Form.” Perspecta 21: 14–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1567078

- Hays, K. Michael. 2010. Architecture’s Desire: Reading the Late Avant-Garde. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Jay, Martin. 2016. Reason after Its Eclipse: On Late Critical Theory. Madison, WI; London: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Kipnis, Jeffrey. 2013. “Toward a New Architecture” [1993]. In A Question of Qualities: Essays in Architecture, 287–320. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 2014. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics [1985]. London: Verso.

- Lahiji, Nadir. 2014. “Introduction: The Critical Project and the Post-Political Suspension of Politics.” In Architecture Against the Post-Political: Essays in Reclaiming the Critical Project, edited by Nadir Lahiji, 1–7. London: Routledge.

- Lahiji, Nadir. 2016. Adventures with the Theory of the Baroque and French Philosophy. London: Bloomsbury.

- Lahiji, Nadir. 2019. An Architecture Manifesto: Critical Reason and Theories of a Failed Practice. London; New York: Routledge.

- Lazzarato, Maurizio. 2014. Signs and Machines: Capitalism and the Production of Subjectivity, translated by Joshua David Jordan. Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e); MIT Press.

- Marazzi, Christian. 2008. Capital and Language: From the New Economy to the War Economy [2002], translated by Gregory Conti. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2013. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. London: Verso.

- Negri, Antonio. 2008. The Porcelain Workshop: For a New Grammar of Politics, translated by Noura Wedell. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine Chrysostôme. 2000. Quatremère De Quincy’s Historical Dictionary of Architecture: The True, the Fictive and the Real, translated by Samir Younès. London: Papadakis Publisher.

- Raunig, Gerald. 2013. Factories of Knowledge Industries of Creativity, translated by Aileen Derieg. Los Angeles, CA.; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rodighiero, Dario. 2015. “The Analogous City, The Map.” http://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/209326.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1976. “La Città Analoga: Tavola/The Analogous City: Panel.” Lotus International 13: 4–9.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1979. Aldo Rossi in America: 1976–1979, edited by Peter Eisenman. IAUS New York: MIT Press.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1979. Aldo Rossi, Projects and Drawings, 1962–1979, edited by Francesco Moschini. Florence; New York: Rizzoli.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1982. The Architecture of the City [1966], translated by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1983. “Architecture for Museums” [1966]. In Aldo Rossi: Selected Writings and Projects, edited by John O’Regan, translated by Luigi Beltrandi, 14–25. London: Architectural Design.

- Rossi, Aldo. 1993. Aldo Rossi: Drawings and Paintings, edited by Morris Adjmi and Giovanni Bertolotto. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Rossi, Aldo. 2008. Aldo Rossi: Drawings, edited by Germano Celant. Milan: Skira.

- Schumacher, Patrik. 2015. “The Historical Pertinence of Parametricism and the Prospect of a Free Market Urban Order.” In The Politics of Parametricism: Digital Technologies in Architecture, edited by Matthew Poole and Manuel Shvartzberg, 19–44. London; New York: Bloomsbury.

- Speaks, Michael. 2005. “After Theory.” Architectural Record 193 (6): 72–75.

- Tafuri, Manfredo. 1998. “L’Architecture Dans Le Boudoir: The Language of Criticism and the Criticism of Language” [1974]. In Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture 1973–1984, edited by K. Michael Hays, translated by Victor Caliandro, 291–316. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Toscano, Alberto. 2008. “The Open Secret of Real Abstraction.” Rethinking Marxism 20 (2): 273–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08935690801917304

- Villari, Sergio. 1990. J.N.L. Durand 1760–1834: Art and Science of Architecture, translated by Eli Gottlieb. New York: Rizzoli.

- Virno, Paolo. 2004. A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, translated by Isabella Bertoletti, James Cascaito, and Andrea Casson. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Virno, Paolo. 2008. “Three Remarks Regarding the Multitude’s Subjectivity and Its Aesthetic Component.” In Under Pressure: Pictures, Subjects, and the New Spirit of Capitalism, edited by Daniel Birnbaum and Isabelle Graw, 30–45. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Virno, Paolo. 2015. When the Word Becomes Flesh: Language and Human Nature [2003], translated by Giuseppina Mecchia. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Virno, Paolo. 2018. An Essay on Negation: For a Linguistic Anthropology [2013], translated by Lorenzo Chiesa. Calcutta: Seagull Books.