This conference aims to think new forms of living, working, and being together. Since Rossi wrote his seminal text The Architecture of the City in which he sought to understand the political forces shaping the construction of the city and McLuhan coined the term global village which anticipated the revolution in digital media, the world population has doubled and telecommunications have expanded to reach everyone. We are rubbing up against each other now more than ever, and yet we are not very good at getting together to collectively address the existential problems that we live with every day. All the indicators – environmental damage and inequality, which are forms of damage to ourselves – suggest that we are very bad at it. Public debate has rarely been so divisive and meaningless; it has never been more important to find new forms of association, new forms of public debate, consensus, and collective action.

We first began thinking about the question of the individual and the collective – how they relate to each other and how they are organized – when the Universities and College Union (UCU) was on strike about pensions in February 2018. The strike was about sharing financial risk: whether the financial risk inherent to pensions should be borne by individual pension-holders or whether that risk should be spread across all pension-holders. At the time, I was reading Vitruvius on campfires – in his view, the first social formation – and Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents. In that text, Freud makes the distinction between feelings of community, which he dismisses as utterly imaginary and misleading, and which always lead to discord, and the real ties that bind individuals to each other into social formations, and social formations into civilizations. He argues that these ties are real. We are bound to each other in real material ways by campfires, by the shared risk in legal and financial instruments like pensions, by membership in unions and universities, and by work, land, customs, law, and principally, by the symbolic codes of language.

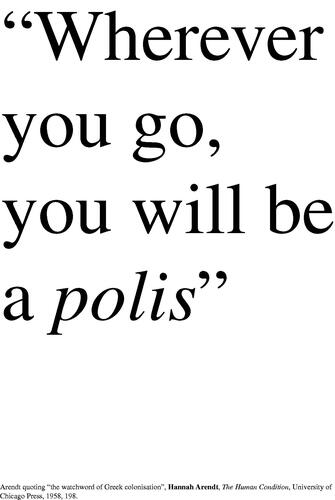

Collective life is a difficult term. Its meaning and significance need to be clarified with each instance of its use. We expect that in some quarters it may create discomfort. We chose the title collective life because we wanted a general term that would draw in as many forms of social practice as possible. We intentionally cast the net wide. We are interested in how the individual and the collective are constructed and reproduced in public and private life, at different scales and forms, in different disciplines, in different places, with the intention of keeping these categories as open as possible to different areas of thought and action. The papers, films, and exhibitions in this conference range over a broad territory. There are papers on buildings, housing, institutions, communities, cities, gender, politics, media, faith, ethics: the list goes on. There are papers on key thinkers on cities and social life, including Arendt, Foucault, Rossi, Lefebvre, McLuhan and Lacan. We are particularly keen to explore the contributions of architecture because it is the practice that thinks and constructs our artefactual world. We also are interested in the roles of research, the humanities, and the University – the institution with a social mandate for intellectual leadership – in building forms of collective intelligence.

More importantly, we chose collective life because it does not correspond to the language that currently populates national and international social, planning, and environmental policy documents. I am thinking of documents like the UN Sustainability Development Goals and language like: place-making, sustainability, resilience, well-being. As laudable as these goals are, there is a nagging doubt about the authenticity of the language in which they are written. It is familiar, predictable, and entirely too cosy with the rhetoric and market-thinking of the entrenched and vested interests that are – arguably – the causes of the existential problems that we face, and that are undermining cities and hollowing out public life.

We wanted – in other words – to use collective life not only as a classification, but as an operational tool for critically rethinking these policy priorities in the way that only the humanities can do. Arguably, the humanities do not invent new things. Whether it is Arendt reading Aristotle, Ockman reading McLuhan, or Holm reading Lacan, the humanities channel the flow of thought on cities and social life, and direct it into new and compelling futures. This thought is at once collective and historic. It is from this position of insight and power that we endeavor to unpack the relations between the environments that we build in order to live well in them and construct the forms of social life that inhabit them.

This conference is a forum for thinking out loud and in public, with the openness, commitment, interdisciplinarity, and criticality that we expect to find in the University. The message of this conference is that sustained critical inquiry into cities and its social life is very much alive and well. Humanities-oriented thinking on cities does not directly respond to the policy priorities that shape our cities and societies, and shapes our university research environment. Rather than being led by them, it anticipates them. Rather than simply complying with them, it frames them. It thinks them anew.