Abstract

This article examines how luxury fashion houses Chanel and Alexander McQueen have mobilized the “spirit” of their founding designers to become part of the commercial brand’s founding myth and vocabulary. Pierre Bourdieu highlighted how within the field of fashion, the creative vision of the designer which should be irreplaceable is in fact replaceable where their products and business can live on long after their death through the succession of another designer. We present the case studies of Chanel and Alexander McQueen as examples of how luxury fashion labels strategically assimilate new designers (Karl Lagerfeld and Virginie Viard in the case of Chanel and Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen) into the mythology of the brand. We develop the phantasmagoria succession framework to explain how founding designers of luxury labels are systematically conjured as “spirits” that inhabit the brand’s seasonal commodities. To establish a link between the past and the future, the “spirit,” “essence” or “aura” of the founding designer is transmitted through the ritual means of the fashion spectacle to a successive designer. We demonstrate here how the mythology of the original designer’s “spirit” is summoned and reproduced by the brand through: the use of mystified storytelling in the fashion press; the consecration of particular fashion products as a chest of symbols; and the ritual acts and spectacular theatricality of catwalk presentations.

Introduction

The problem of succession in the field of fashion was astutely raised by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Recognizing that designers must be interchangeable, despite the fact that “unique” creative direction is paramount to the aura of haute couture, Bourdieu contends: “here we have a field where there is both affirmation of the charismatic power of the creator and affirmation of the possibility of replacing the irreplaceable.”Footnote1 Bourdieu specifically provides the example of Gaston Berthelot’s succession of Gabrielle Chanel in 1971. Drawing on Max Weber’s theory of charismatic succession he asks: “how can the unique irruption which brings discontinuity to a universe be turned into a durable institution?”Footnote2 At the time of Chanel’s death, the fashion house released a statement, reported in the New York Times that:

Mr Berthelot would not create original designs for the future Chanel collections since the house would continue to follow the style of Chanel. He will … “supervise and coordinate” the work of the five tailors and fitters who worked closely with Chanel. They will continue to make Chanel clothes from designs she left upon her death.Footnote3

From this moment on, the Chanel brand would come to rely on the essence of its founding designer – Gabrielle Chanel, to reinvigorate its seasonal offerings.

Berthelot was ultimately unsuccessful in the role at Chanel because he was not able to promote his own distinct vision for the brand. As Bourdieu reasons, he was unable to mobilize collective belief in his ability to create haute couture, and therefore was not consecrated in the eyes of the agents who create fashion.Footnote4 However, the 1983 appointment of Karl Lagerfeld at Chanel, followed by Virginie Viard in 2019, demonstrates that successful succession is possible within the field of luxury fashion brands. Indeed, numerous fashion brands including Dior, Saint Laurent and Alexander McQueen have continued to operate after their founder’s death under the creative directorship of other designers. In 2019, The Business of Fashion overviewed recent succession planning, arguing that disruption and continuity are the two major motivations that underpin decisions regarding who will take over creative direction of established luxury labels.Footnote5 These decisions are financially driven by global multinational corporations. Continuity is seen as important when heritage is a core brand value and labels are financially performing well amongst brand loyalists, while disruption is seen as a strategy to bring new consumers from emerging markets to a brand (for example Alessandro Michele at Gucci, who stepped down in December 2022).Footnote6 For both Chanel and Alexander McQueen continuity was central to both brands’ ability to drive financial growth as they rely on consumer’s strong affiliations with existing codes, values and essence. What this essence is, however, is not explained.Footnote7

The central argument of this article develops the case studies of Chanel and Alexander McQueen, to contend that successful succession is not just a matter of the anointment of a designer and the affirmation of their charismatic power as a creator, but rather that continuity is constructed by invoking the “spirit” of the original designer after their death.

This “spirit,” “essence” or “aura” can be understood as a type of phantasmagoria – an illusion that conceals the workings of capitalist production and consumption. We use these terms interchangeably, as is the norm in luxury fashion media. In some instances, the spirit or essence may refer to the unique creative perspective of a founding designer that resurfaces in successive designer’s collections. These terms are also used to evoke the ghost-like presence of a founding designer that continues to inhabit a brand’s symbolic value. In either case, as we demonstrate here, the mythology of the original designer’s “spirit” is summoned and reproduced by the brand through, the use of mystified storytelling in the fashion press; the consecration of particular fashion products as a chest of symbols; and the ritual acts and spectacular theatricality of catwalk presentations. As we observe here, succession and resurrection in luxury branding requires tricky slights of hand to simultaneously exalt the creativity of subsequent creative directors while retaining elements of the original designer’s repertoire. We argue that, through the phantasmagoria spectacle, the designers Gabrielle Chanel and Alexander McQueen are immortalized in words, objects and images. They become further commercialized due to their death, while simultaneously assimilating subsequent successive designers (Karl Lagerfeld and Virginie Viard in the case of Chanel, and Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen) into the illusion of immortality and timelessness of the fashion brand.

Chanel and Alexander McQueen have been selected as case studies as both luxury fashion houses have continuously drawn on the discourse of the founding designer’s “spirit” influencing the collections of subsequent designers. Other brands, such as Dior, could be similarly analyzed. Yves Saint Laurent and Marc Bohan have “undeniably helped to maintain the ‘spirit of the creator’ after his death,”Footnote8 while John Galliano, Raf Simons and Maria Grazia Chiuri have been “able to refresh the brand image while retaining the Maison’s initial spirit.”Footnote9 There is also a case to be made, beyond the scope of this article, where luxury brand succession has demonstrated a distinct disjuncture. For example, Balenciaga’s legacy of sculptural haute-couture under Christobal Balenciaga appears far removed from Demna Gvasalia’s current street-wear inspired creative direction. Chanel and Alexander McQueen are relevant case studies to examine here as the original designers appear to comply with Bourdieu and Delsaut’s analysis of the “magic” of haute couture.Footnote10 They argue that particular founders of fashion houses make their mark by being fashion initiators of a new style that influences others, that is, they create symbolic distinction for certain styles that are seen as revolutionary at the time. For Gabrielle Chanel this was the little black dress (1926), for Alexander McQueen, the bumsters (1995). These two distinctive luxury fashion labels also represent what Bourdieu and Delsaut describe as the two dominant positions within the field of high fashion, that is, the conservative and traditional style of “old” fashion houses (Chanel) and the avant-garde youthful style of the “new” (Alexander McQueen). By comparing these seemingly disparate luxury fashion brands we demonstrate that phantasmagoria in the fashion system is an ongoing strategy of reification that treats the spirit of a past founding creative director as a commodity.

Phantasmagoria and the fashion system

In his essay, Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century, Walter Benjamin examines the fantasy of the commodity system where products are able to transcend the realities of their production through ideal images that aspire to break with what is outdated to create the new.Footnote11 However, this image of the new is dialectic – a space where past and present collide in the collective consciousness to produce a dream-like fantasy. To explain this, Benjamin uses the metaphor of phantasmagoria to elucidate how the bourgeois class is enthralled by the spectacle of luxury goods and their display.Footnote12 The phantasmagoria of the nineteenth century were magic lantern shows, a form of popular spectacle that used optical illusion to make ghostly figures of the dead appear to the audience through back-lit projection that hid their means of production from view. In the case of fashion we can understand the concept of phantasmagoria as a specter of the past in the present, which occupies a tenuous space between the imaginary and the real. Its spectacle emulates a sense of the sacred and the sublime in everyday experience. Like other commodities, fashion creates experiences of fantasy and reverie to conceal capitalist production through marketing and retail strategies. The concept of phantasmagoria is useful to our argument as we explain how founding designers of luxury labels are conjured as “spirits” that inhabit the brand’s commodities. To establish a link between the past and the future, the “spirit,” “essence” or “aura” of the founding designer is transmitted through the ritual means of the fashion spectacle to a successive designer.

In her seminal account of fashion at the turn of the millennium, Caroline Evans draws on the concept of phantasmagoria to explain the way that fashion uses the spectacle of the runway show to create a dream world for fashion garments, hiding the reality of commodity culture and production.Footnote13 Drawing on Karl MarxFootnote14 and Theodore AdornoFootnote15 who used the term as a metaphor for the workings of commodity fetishism, Evans explains how catwalk productions by the likes of Alexander McQueen, Martin Margiela and Viktor & Rolf in the 1990s adopted spectacular theatricality to divert attention from fashion’s systems of privilege.Footnote16 These innovative catwalk shows which used theatrical ostentation to dramatic narrative effect paved the way for fashion’s current popularized and normalized extravagant performances and images while blurring the lines between art and fashion luxury brands. In some cases, as Evan’s outlines, almost literal interpretations of fashion’s ghostly qualities reveal the phantasmagorical workings of the system. For example, Alexander McQueen’s Elect Dissect (AW/97–8) collection for Givenchy in which models were represented as ghosts.Footnote17 Evans argues that 90s fashion’s predilection for representing death and decay through haute couture fashion can also be understood through the paradigm of phantasmagoria. She argues of McQueen’s Voss catwalk show (SS/2001) that: “By putting beauty and horror together, the show exemplified … [what] in Adorno’s account [is] intrinsic to phantasmagoria: ‘The conversion of pleasure into sickness,’ and sex into death.”Footnote18 The analogy here between the dialectics of beauty, pleasure, sex transformed into decay, sickness and death, alludes to the capacity of luxury fashion consumerism to obscure its destructive systems of production with the glamour of spectacle and illusion. The fashion system primarily values images of beauty, youthfulness and the new, yet, each season as styles become outmoded they decay and die, to be renewed again at a later point for the cycle to begin again.

Benjamin also wrote of fashion’s relationship to death with a suggestive epigraph in Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century: “Fashion: Mr Death! Mr Death! Leopardi Dialogue between Fashion and Death.”Footnote19 His suggestion being that fashion is temporary, and in a constant state of death and renewal. The relationship between fashion and death has been similarly theorized by Jean Baudrillard where he argues that fashion is based on an aesthetic of renewal, that beyond the death of a style of fashion there is a chance of a second existence: “the enjoyment of fashion is therefore the enjoyment of a spectral and cyclical world of bygone forms endlessly revived as effective signs.”Footnote20 Fashion then can counter death, because of this constant recycling and renewal, where Baudrillard claims that: “the desire for death is itself recycled within fashion, emptying it of every subversive phantasm and involving it, along with everything else, in fashion’s innocuous revolutions.”Footnote21 Baudrillard positions death and renewal as an integral element of the fashion system and its enchanting spectacle. This echoes Benjamin’s phantasmagoria, and helps us to understand that the succession of fashion designers as artistic directors of luxury labels is yet another version of death, recycling, and reinvention that underpins the fashion system.

As we will outline in the following sections, Gabrielle Chanel and Alexander Lee McQueen are positioned as phantasmagoria “spirits” or “ghosts” within fashion luxury brands. Their deaths provided the opportunity for their mythic personas, iconographies and aesthetic cues to be resurrected by subsequent designers to create an enchanting spectacle of immortality, providing aura and immaterial value to the brand. Through this spectacle, Gabrielle Chanel and Alexander McQueen become the ultimate glorified commodity, fetishized objects of fascination and adoration where the aura of the designer becomes disseminated across all products and services.

In the following we will elucidate how these luxury fashion brands operate within what we term the phantasmagoria succession framework. This framework considers the triumvirate system of representation through word, object and image that underpins fashion consumption. We argue this through examples of mystified storytelling in the fashion press that draws on the language of phantasmagoria – spirit, essence and aura – to insert the mythology of Gabrielle Chanel and Alexander McQueen into contemporary fashion contexts. We consider how Chanel’s and McQueen’s fashion objects draw on a chest of symbols from the original designers’ archives to become consecrated as icons embedding this mythology into the brands’ commodities. Finally, we contend that this mythology becomes tangible fantasy through the ritualized magical acts of the fashion show, where the consumer is invited to witness the spectacularization of creative vision through the illusion of immortality.

Resurrection in the fashion media

The “Spirit of Chanel” – the ongoing presence of Gabrielle Chanel’s aesthetic in the brand’s collections is a recurring theme in the fashion press. Whether an advertorial espousing the essence of Chanel in accessory form,Footnote22 or an article informing readers how Chanel’s “mystique” is still part of the brand’s identity,Footnote23 the ghost of Gabrielle Chanel surfaces as the creative origin of collections past, present and future.Footnote24 Through-out Lagerfeld’s reign as creative director fashion critics pointed to the presence of Chanel’s spirit as integral to the brand’s success. For example, Robin Givhan’s review of the AW/1998 runway, with its references to 1920’s cloche hats adorned with camellias and drop-waist black dresses, implores that:

This collection also is instructive of what it means to maintain a fashion house after the death of its founder. Each garment in this line in some way evoked a memory, a fantasy or a reverie about the house of Chanel.Footnote25

This conjuring of ghosts has also recently been attributed to Viard’s collections, with claims that “the ghost of Lagerfeld is receding … pivoting the brand from his legacy and back to its roots, reconnecting the house to the life and work of Coco Chanel.”Footnote26 Similarly, for SS/2022 Viard spoke to the press about the collection as a “conversation that crosses time” with Gabrielle Chanel and Lagerfeld: “I like the similarity of spirit between us, now and across time.”Footnote27 In this way the present creative director is positioned as medium, communing with the dead, in order to keep the brand alive. In this example it is evident that the fashion press plays a crucial role in consecrating the heir to the fashion label as a legitimate creative force. However, their success is not based on the new creative director’s fashion-ability and innovation, but rather their ability to seamlessly translate recycled past styles into the new. Bourdieu’s previously mentioned critique of succession at Chanel argues that Berthelot was not able to exert his own creative vision as an haute couturier as he simply oversaw Chanel’s previously designed collections as if she was looking over their production under his expertise.Footnote28 We argue that in the contemporary fashion system the phantasmagorical sleight of hand occurs where the discourse surrounding the incoming creative director reveres the translation of the old icons into a configuration that appears new. That is, fashion that is dead and past, is cast as an apparition of the now and the future.

The magical manifestation of the designer’s creative vision through supernatural conversation demonstrates how phantasmagoria operates as a mechanism that infuses fashion with the quality of timelessness and the essence of creative legitimacy. In a 2003 article for Harper’s Bazaar magazine Karl Lagerfeld indulges in a quirky tête-à-tête with Coco, imagining what the two designers might say to each other.Footnote29 Lagerfeld reinvigorates the Chanel myth by conjuring how the specter of Gabrielle is still present in the brand’s creative direction: “KL: The spirit of Chanel was also well preserved, because your name and the business fell into the right hands. Look what happened to the other names of your day.”Footnote30 Karl and Coco continue in this manner, discussing how she is irreplaceable. However, she also compliments him on what he does in her name and they reminisce about Coco’s contribution to fashion in her time. The conversation ends with a reflection on the spirit of the designer: “KL: We are all finally weak and mortal. CC: I am not! I am eternal! I am immortal! If not, we could not have had this conversation.”Footnote31 In this exchange the fashion press positions Gabrielle Chanel as an immortal influence on Chanel the luxury brand’s style, and Lagerfeld is assimilated into her myth.

After the death of Lee Alexander McQueen in 2010, and the subsequent succession of Sarah Burton at the helm of the label, the spirit of the founding designer was often evoked by the fashion press. In an attempt to establish continuity while heralding the influence of her own “more feminine” creative vision Burton stated that: “There will always be this McQueen spirit and essence. But, of course, I'm a woman so maybe more from a woman’s point of view.”Footnote32 Having worked alongside Lee McQueen for fourteen-years before his suicide, Burton was the obvious choice for the Gucci Group when deciding the brand’s future, despite speculation that more established names such Gareth Pugh or Olivier Theyskens might take over.Footnote33 Press releases at the time praised Burton’s “deep understanding of [McQueen’s] vision” and that she intended “to stay true to his legacy.”Footnote34 This demonstrates the brand’s commercial understanding that smooth succession requires at least lip service to a continuation of the unique creative vision of the founding designer. Certainly, Burton’s successful reign at Alexander McQueen has often been underpinned by the casting of her predecessor as a “creative genius” and that by “staying true to McQueen’s spirit” she has been able to keep the brand alive in difficult times.Footnote35

In contrast, Lee McQueen’s succession as creative director at Givenchy in 1996 (after a brief stint by John Galliano before he went on to Dior) made no attempt to continue the tradition of Hubert de Givenchy’s old-world elegance. Instead, it was wholly expected that McQueen would bring a disruptive force to the brand. He achieved this disjuncture with collections such as Elect Dissect (A/W 1997) which contrasted black leather, lace and taxidermy to Gothic affect—an aesthetic distinctively different to Hubert de Givenchy’s floating ball gowns and shimmering sheaths. Bernard Arnault, president of the LVMH group of which Dior and Givenchy are a part, orchestrated a transformation of traditional haute couture by employing young, controversial British designers known for producing theatrical spectacles with the aim of attracting media attention and appealing to a new generation of consumers. At the time, the press exalted just how different Alexander McQueen was to Hubert de Givenchy, claiming his appointment as “positively anarchic.”Footnote36 The contrast between continuity and disruption follows Bourdieu’s argument regarding the difference between old and new fashion houses where: “these struggles between the establishment and the young pretenders … the challengers … who take all the risks, are the basis of the changes which occur in the field of haute couture.”Footnote37 Evoking the spirit of the founding designer instead suggests there is no change, Alexander McQueen, the once disruptive force becomes a symbol of continuity for his own brand where, as his eponymous house states on its website: “His brave and beautiful spirit touches everything we do, always […].”Footnote38 Like Gabrielle Chanel, Lee Alexander McQueen is immortalized in the media and through discourse that casts him as a continual presence that shapes the fashion brand. The fashion media’s role in seasonally resurrecting a past designer’s spirit to inhabit the brand is directly related to the brand’s continuous renewal of previous styles and symbols as new products.

Renewal through a chest of symbols

The blurring of lines between religion, art and fashion luxury brands, along with the ability to disrupt continuity are key components of successful luxury brand management and subsequent creative direction succession.Footnote39 They are also key to the systematic process of infusion or creation of aura within the phantasmagoria succession framework. Art, religion and luxury are meaning-making cultural fields and social processes which explore the intangible, immortality and the sublime.Footnote40 For Bourdieu, the field of production of haute couture shares the same social structure and distinction strategy as the field of high culture, both dealing with intangible and transcendental creative powers.Footnote41 In the case of luxury fashion, immortality is translated into a quest for timelessness through tangible iconic products.Footnote42 As designers, Gabrielle Chanel and Lee Alexander McQueen created very distinct, imaginary dream worlds, iconic products and visions of beauty for their eponymous luxury brands. Both creative directors were able to successfully blur the lines between art, religion and luxury fashion through their creative originality and charismatic power. Chanel and McQueen disrupted fashion of their time by materializing changes or shifts in society through a distinct aesthetic sensibility. They both developed discontinuity within the fashion system they were working in manifested through the eclectic array of signets, logos and stylistic elements that make up the chest of symbols and iconic products of both luxury brands. What was once disruptive under the original creative direction of Gabrielle Chanel and Alexander McQueen becomes continuous through the phantasmagoria succession model.

Luxury brands have a chest of symbols astutely recognized by those who are familiar with the brand or have the cultural capital to understand the brand’s founding myth and mystified storytelling branding strategies.Footnote43 We argue that these symbols are positioned to embody and perpetuate the original creative directors’ “essence” or “spirit.” As such, they assist in asserting the brand’s legitimacy and timelessness in the fashion system. The chest of symbols is eclectic in nature, entangling biographical or intimate experiences of the original creative director, along with their visionary understanding and materialization of their times. For example, Chanel’s iconic products such as the little black dress, tweed jacket or marinière shirt, used design codes from menswear and sportswear as indicative symbols of a shift at the time of women’s roles in society. The austere nature of Chanel’s designs can signify modernity as well as the severity and simplicity of her early life.Footnote44 Gabrielle Chanel epitomized the modern woman, positioned at the beginning of the twentieth century. She rearranged style to fit in the fashion system, and reimagined women’s clothing by giving new functions to a range of common materials. In doing so, “she disrupted the way fashion’s signifying practices had run parallel to, had mapped onto, those of gender and class.”Footnote45

McQueen’s chest of symbols similarly draws inspiration from the social changes of the twenty-first century along with his own lived experience. In fact, the McQueen brand was capitalizing on the founder’s personality even before the death of Lee McQueen, where he stated that: “I want to be the purveyor of a certain silhouette or a way of cutting, so that when I’m dead and gone people will know that the twenty-first century was started by Alexander McQueen.”Footnote46 His technical virtuosity along with his constant pushing of boundaries were instrumental in defining how women looked at the beginning of the century.Footnote47 McQueen developed new silhouettes for women, such as the bumster low-cut trousers, revealing a new erotic point, the bottom of the spine which elongated the body and also brought a new element of masculinity to womenswear. He added further complexity by juxtaposing hard and soft materials such as leather and lace, precise tailoring with fluid fabrications, and found natural materials alongside opulent silhouettes. McQueen’s dark and romantic ideas were materialized into exquisite fabrics. The interplay between opposites, generally pivoting between lightness and darkness, life and death, sex and violence were poetically translated into garments that were difficult to differentiate from the creative director’s personal fantasies and as such they transcended their materiality.Footnote48 The creative originality of both Alexander McQueen and Gabrielle Chanel that is the origin myth of the now “mystified past” of the luxury brand can be therefore symbolic and even spiritual or religious in nature. Fashion and religion navigate materiality and immateriality, reconcile tradition and change.Footnote49 In doing so, the blurring of lines between art, religion and luxury fashion is fundamental for the construction and subsequent renewal of a successful chest of symbols.

The “spirit” or “essence” of Chanel and McQueen that the brands continue to capitalize on after the founders’ death can be understood as an aura-infusing or aura-manufacturing device. Successful luxury brands are inherently auratic.Footnote50 Aura in art and luxury is recognized as the cultural transfer of belief from the sacred to the secular; an essence of authenticity that is present in time and space.Footnote51 For Benjamin, aura and authenticity can only exist in the presence of the original art.Footnote52 Luxury brands use storytelling around a mythologized past and founder to recreate legends, idealizing and chasing the original work of art (which in this case is the original creative director/founder). Bourdieu and Delsaut refer to this tactic of recreation when discussing the artistic and commercialization strategies that French fashion houses use to distribute and maintain cultural capital as well as assert their dominance.Footnote53 For Bourdieu and Delsaut, this is achieved in a similar way to art merchants, by effecting awe, provoking surprise and wonder in their audiences, the spirit is thus absorbed and distracted from the fact that the real art (when the designer/founder is no longer there) is absent.Footnote54 This can be observed in the spectacular theatrical nature of fashion shows and also in the way Viard and Burton access season after season this “essence” or “spirit” through the chest of symbols that make up Chanel’s and McQueen’s patrimony. The “spirit” or creative originality of the designer is seen to be present in the brand’s products and images that are resurrected cyclically, creating an illusion of immortality for luxury brands.

Aura is commercially activated and managed through the reiteration and renewal of a luxury brand’s patrimony season after season. That is, the recirculation of the brand’s chest of symbols. After Gabrielle Chanel’s death, the brand was able to stand the test of time due to the constant renovation of symbols that are anchored in the brand’s identity. Karl Lagerfeld identified these never changing and immediately recognizable elements of the chest of symbols in 1991 and named them “Chanel patrimony.”Footnote55 These are: the black and tan shoe (1957), the quilted black bag with the golden chain (1957) the little black dress (1924) the byzantine cross jewelry (1930) the tweed jacket (1956) the hair tie (1958) and the camellia flower (1939).Footnote56

Chanel’s patrimony offers numerous illustrations of the relationship between religion, art and luxury fashion, that create the illusion of immortality and timelessness through the chest of symbols. For example, the Chanel brand continues to draw inspiration from religious and esoteric motifs in the brand’s costume jewelry range introduced in the 1920s.Footnote57 The jewelry collections are inspired from the Byzantine period to the Baroque, ancient Egypt to India, signs of the zodiac, astrological symbols and so on.Footnote58 The exoticized use and reuse of symbols such as Maltese crosses and pendant crucifixes along with the use of symbolic materials, demonstrate Chanel’s ability to create luxury products drawing from Coco’s own life experiences that can be both timeless and innovative, decorative and symbolic, sacred and profane. Gabrielle Chanel looked to her humble beginnings and severe upbringing at a catholic orphanage as well as collaboration with her artistic and bohemian social circle to create her jewelry range.Footnote59 She layered austere and minimal silhouettes with extravagant and opulent costume jewelry, creating a juxtaposition that both materialized her life experiences and innovated womenswear at the same time (). Both Lagerfeld and Viard continued to circulate the costume jewelry range season after season. They recreate and modernize myths around these iconic products and the aura they convey. Successful creative direction succession consists therefore, of the perpetual tension of innovation and timelessness through the creation and promotion of auratic goods. According to Lipovetsky and Roux, a luxury brand needs to elevate its image to the status of legend in order to fully represent what luxury is, and this is not done through the promotion of expensive objects, but through the construction of the brand’s mythology.Footnote60 In the case of Chanel, the “essence” or “spirit” of Chanel is captured in the apparent auratic materiality of the brand’s chest of symbols. That is, the entanglement of her mythologized private life with the brand’s commodities. The chest of symbols is therefore folded into the circulation of commodified immortality within the fashion system and its enchanting spectacle.

Expanding on the paradigm of phantasmagoria and commodity fetishism, the apparent “summoning” of Lee McQueen’s “spirit” and life experience as an essential component of the brand’s mythology can be identified through the contemporary designs of Sarah Burton. Lee McQueen was aware of the importance of legacy and mystified storytelling in order to create a luxury brand. He mastered the art of the spectacle and theatrical ostentation through fashion and its performance on the catwalk. His interest in the ghostly and the gothic permeated his work from his introduction to the fashion industry until his very last (posthumously shown) collection. Indeed, as McWade suggests, “McQueen’s entire presence has been marked by the spectral – an air of ghostliness hovers over his memory and legacy as a designer.”Footnote61 McQueen’s iconic SS/1999 runway show featured supermodel Shalom Harlow standing like a ballerina on a rotating platform, wearing a white showpiece dress that is spray painted by robots. Blurring the lines between performance art and dystopian science-fiction, the dress was immediately immortalized as a magical illusion on the catwalk. The white dress is an example of a showpiece, as Evans describes:

Contemporary fashion enters the realm of the commodity and circulates obliquely, not always as an embodied practice but sometimes as an image, an idea or a conceptual piece. It is in this sense too that the showpiece is ghostly or spectral.Footnote62

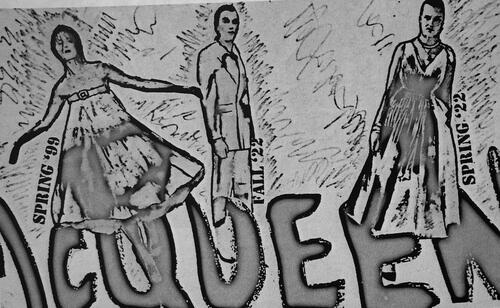

This performance showpiece has been resurrected in subsequent ready-to-wear 2022 collections for the brand (). Twenty years after its initial apparition, the improvised and theatrical spray-painted marks are now a fixed component of the chest of symbols and patrimony of the luxury brand. Through these references the brand invites customers to travel to the past and experience the initial awe produced by the performance while also introducing new customers to the brand’s archives. As such, the spray-paint marks can be commodified and renewed season after season under the pretense of heritage and brand continuity. The spray-paint iconography embellishes both menswear and womenswear ready-to-wear garments, including double-breasted tailored jackets and cigarette pants, following the distinct tailoring virtuosity that is also part of McQueen’s artisanal legitimacy. The resurrection of these textures can be understood as an example of the summoning of the “spirit” of the designer in an attempt to manufacture aura and keep the brand alive. This continuous, seasonal reproduction of symbols is consistent with the brand’s identity and mythology, creating an illusion of immortality by folding the past into the present. However, it contrasts with what was impactful and valuable in the 1999 runway show, namely the unexpected shock value and awe that McQueen was able to produce in his audience through the spectacle of its presentation. The auratic quality of the catwalk performance of the No.13 showpiece dress when reproduced as simply textural materiality on ready to wear garments is transformed into what Benjamin might describe as a mechanical image of reproduction.Footnote63 While the aura of the original might be diluted, the phantasmagoria spectacle is manifest through the reappearance of the past in the present. In this case, contemporary fashion images are, according to Evans: “bearers of meaning and, as such, stretch simultaneously back to the past and forward into the future.”Footnote64 The chest of symbols that luxury fashion brands reproduce in the phantasmagorical renewal of the past extends beyond the material manifestation of fashion objects and is also surfaced in the rituals of the catwalk.

Illusions and magical apparitions on the catwalk

From a luxury brand management perspective, and in the spirit of keeping the fashion system recirculating, commodities are devised as an illusion of immortality, where the representation of the creative director as artist or magician is vital.Footnote65 Therefore, systematic infusion of aura can also be understood as an infusion of magic. Charismatic creative directors are described as having special, otherworldly attributes, and they perform their talents much so as magicians do in the spectacle of fashion. Alexander McQueen and Gabrielle Chanel not only created singular and original aesthetic visions, they also had the “magical power” of creation. In this framework, the creative director is a kind of magical being who not only passes on their revelation but also “transmutes” (rewrites) codes of beauty and fashion, creating a distinctive imaginary world.Footnote66

Both Chanel and McQueen’s magical acts need to be actualized and legitimized through ritual mediation, and this happens at the fashion show where the audience witnesses the intangible myth or illusion of the commodified spectacle become a tangible fantasy. Chanel’s and McQueen’s specters are supposedly conjured, and the magician’s illusionary act legitimized through the fashion show. Fashion shows constitute the most important collective ritual consecration.Footnote67 Here we find the principal properties of magical ritual: repetitive formal and normative sequencing and a ceremonial cadence, as discussed by Arnould et al:

The fashion show ritually mediates between artistic directors, and their special publics, and through which their artistic genius and its imaginary “dream” is legitimised: People buy the dream, the immaterial, the impression of becoming chic. It is an accession to the immaterial. The dream, it must rely upon the real, it must be legitimate. Haute couture is there to maintain the dream. People project themselves into the models that wear the clothes in the shows.Footnote68

The fashion show as a ritual act is thus another aura manufacturing device that blurs the line between art, religion and luxury fashion. For example, Alexander McQueen, as a romantic, was able to provoke awe and shock value to invoke the sublime through the unrestrained and heightened emotionality of the spectacle of his runway presentations. His fashion collections entangled themes of life and death on the catwalk. As such, it can be argued that the aesthetic experience of the sublime that McQueen explored through his collections bears close resemblance to ritual or fashion as spectacle. This type of aesthetic perspective, according to Baudrillard, “allows us to assimilate fashion to the ceremonial.”Footnote69 McQueen’s death further reinforces this, as he symbolically becomes assimilated into the ceremonial as part of the brand’s luxury strategy when he is resurrected on the catwalk through reference to past fashion shows.

Chanel’s fashion shows recreate the mythology associated with Coco Chanel by conjuring the spirit of the brand and Chanel’s specter. This is achieved through the renewal of iconic auratic products and is enhanced by the brand’s vision of beauty channeled through the models and brand ambassadors that walk the fashion shows. Chanel carefully chooses models, actresses and other public figures that are known for sharing some of the personality and physical traits of Coco Chanel.Footnote70 This illusion of immortality is extended beyond the corporeality of Coco Chanel to the physical places she inhabited. For example, for the Haute Couture SS/2006 collection, Lagerfeld carefully crafted a dreamlike scenery blending the iconography of the brand with theatrical backdrops and installations (). Placed at the center of the Grand Palais in Paris, a white tower recreated the mythical staircase of apartment 31 Rue Cambon, where Gabrielle Chanel sat, unseen, season after season to observe the reactions of the audience as each of her collections was presented.Footnote71

In this 2006 show, the models walked down the spiral staircase, signifying eternity and timelessness, a connection from heaven to earth, as if the immortal ghost of Chanel had dressed them herself, carefully supervising and controlling every detail of the catwalk looks. The tower’s white walls, seem to symbolically conceal, the invisible labor of the haute couture workshops and the women that craft under the spirit’s supervision, (as according to the brand’s myth) the exquisite garments. The Chanel rue Cambon staircase was again resurrected as a centerpiece for Viard’s 2019 Métiers d’Art collection highlighting the work of the brand’s artisan ateliers in a 1980s inspired collection.Footnote72 Working with the film-director Sofia Coppola, the staircase and Chanel’s apartment were recreated on a Hollywood scale at the Grand Palais, Paris. The fashion press described the catwalk performance as drawing a line of succession between Viard and Coco, where “the ghost of Coco was more strongly felt in the Rue Cambon headquarters than anywhere else.”Footnote73 Through the symbolic function of the staircase the specter of Coco Chanel comes alive and the aura of the brand is revitalized and legitimized through the ritualized illusion of images of the past and present colliding, in an “eternal recurrence of the new”Footnote74 and as such creating the phantasmagoria spectacle.

This ritualized illusion of images of the past colliding into the present, can be identified in the symbolism of the staircase and the repetition of movement and garments in the fashion show. Benjamin regarded fashions as expressions of a non-linear mode of historical time- as a sort of eternal return,” where fashion makes the cyclical nature of time visible.Footnote75 Fashion measures time through ritualized repetition. Gabrielle Chanel’s original catwalk shows were based around the spectacle of the mirrored staircase and the repetition of models in motion refracted across its surfaces, Lagerfeld’s tribute to the staircase in 2006 and Viard’s recreation of it in 2019 make the cyclical passage of time visible. Chanel relies on this repetition to recreate and renew the brand’s chest of symbols (of which the staircase is a part). The repetition of the same garments, design vocabulary, and vision of beauty is embedded in the brand through the illusion of Coco Chanel’s magical founding myth spectacularized through the catwalk performance. This illusion perpetuates the cycles of simulation and commodity fetishism.

The theme of death permeated many of McQueen’s collections, design motifs such as the skull, the use of animal taxidermy, and human hair as a reference to mourning jewelry, are literal reminders of memento mori. These themes elided with McQueen’s public persona when discussing the dark side to his collections: “It is important to look at death because it is a part of life … It is the end of a cycle – everything has to end.”Footnote76 McQueen often referred to himself in the past tense and was insightful about his eventual departure from the helm of his brand: “I want this to be a company that lives way beyond me … When I’m dead, hopefully this house will still be going.”Footnote77 After McQueen’s suicide, the mythology of death continued to contribute to the sense of the spectral that is vital to the brand’s identity. Angels and Demons (A/W 2010) is another example of the commodification of death and illusion of immortality. According to fashion theorist Nathalie Khan, McQueen was “simultaneously absent and present in the show which was haunted by that metaphorical presence.”Footnote78 McQueen invested himself in his work both literally and symbolically, from incorporating parts of his own body into his graduate collection to being the subject of resurrection in various symbolic senses such as the Met Gala show Savage Beauty.Footnote79 In this sense, McQueen is an example of how a creative director is commodified into the ultimate object of adoration, transcending life and death and folding into the eternal cycles of consumption of the fashion system.

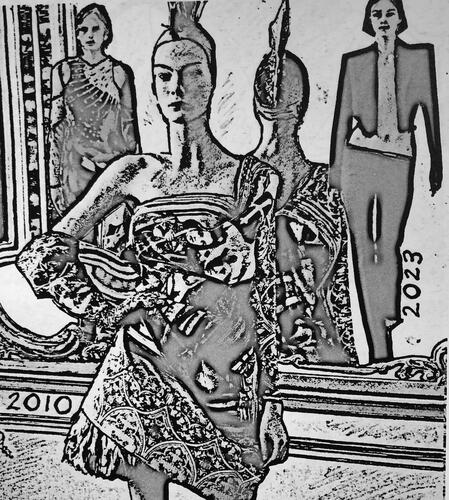

Additionally, circling back to the resurrection of Alexander Lee McQueen in Sarah Burton’s collections for the brand, her SS/2023 fashion show pays homage to the chest of symbols of McQueen’s patrimony (). McQueen’s posthumous collection Angels and Demons showcased Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) paintings on digitally printed fabric that sensuously shaped the sixteen-piece collection.Footnote80 The show highlighted the relationship of the fashion show with art and theater along the formations of image and desire that are central to capitalist spectacle.Footnote81 McQueen’s last show was private, emotional and full of religious symbolism. There were allegorical angels battling with demons on the garments and the show abruptly ended with the whispered words “there is no more.”Footnote82

Thirteen years after this the iconic final show, Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights is once again resurrected, this time, not through the performative nature of McQueen’s theatrically ostentatious catwalk shows, but through the focus on the reproduction of images, such as the zoomed-in digital prints and elevated embroidery placed on skin tight bodysuits by Sarah Burton in 2022. Burton not only played with McQueen’s romantic storytelling tropes such as life and death, destruction and beauty, by recycling Bosch’s paintings; she also resurrected the characteristic sharp tailoring of the house, the iconic bumster pants. Renewing archival references demonstrates how luxury brands rely on the illusion of immortality and commodification of death. When Burton was asked in a Vogue interview why she returned to the Bosch references of Angels and Demons, she replied: “It’s the times we’re living in now … It feels almost like we’re in another Dark Ages in many ways. It’s something we’ve always looked at, at McQueen. Life, death, destruction, beauty. It’s all there. Maybe ….”Footnote83 Burton is therefore, hunting for both images and narratives for reuse in the brand’s archives, introducing new customers to iconic products. By doing so, as Evans argues, “the fashionable moment that constantly collapses into the outmoded realigns the present as it goes, transforming it into a past that it will one day revive as it trawls through it for new motifs.”Footnote84

Conclusion

Through the case study of luxury brands Chanel and Alexander McQueen we demonstrate how a component of successful creative succession after a founder’s death resides in the illusion of immortality and commodification of death that makes part of a luxury brand’s mythology and the capitalist spectacle of the fashion system. Once the luxury brand’s original founder and creative director dies, their “spirit” or “essence” is summoned and reproduced to become a commodity for the luxury label to capitalize on through a system of aura creation that we term the phantasmagoria succession framework. This framework reveals how fashion commodities can be infused with the quality of timelessness and immortality.

The illusion of immortality and the blurring of lines between art, religion and luxury fashion are key components of the ceremonial and spectacular aspect of the phantasmagoria succession framework. Through the examples of Chanel and Alexander McQueen, these phantasmagoria drivers can be materialized through the continuous mystified storytelling in the fashion press, renewal of a chest of symbols that draws on the original designers’ private life and charismatic personality, and the ritualized magical acts of the fashion show. As such, immortality becomes the ultimate sign of luxury, as it assists in mythologizing and legitimizing luxury fashion’s apparent inaccessibility. Immortality matters, as according to Baudrillard:

Immortality … is where the basis of the real discrimination lies, and that nowhere else are power and social transcendence so clearly marked than in the imaginary. The economic power of capital is based in the imaginary just as much as is the power of the Church capital is only fantastic secularisation.Footnote85

The fashion system symbolically imitates rhythms of life and death, with seasonal and cyclical collections of newness and redundancy. The death of a founding designer of a luxury fashion label and their subsequent succession by another designer in some ways paradoxically challenges this cycle as it signals to the illusion of timelessness and immortality. The phantasmagoria succession framework reveals the multiple ways that luxury fashion brands commoditize the death of founding designers in ways that allow them to resurrect the founding designer’s creative legitimacy mediated by a successive designer in order to recycle past designs and present them as “new.” The fashion media assists in positioning luxury as an intangible system of privilege and spectacle, by amplifying and echoing the mythological and esoteric nature of luxury that is closely linked to the social and symbolic functions of religion and art. Conjuring the “spirit,” “essence” or “aura” of a past designer through fashion media discourse, and symbolic heritage cues across fashion objects, images, and catwalk shows fetishizes that designer to the point where they too become a glorified immortal commodity.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Juliana Luna Mora

Dr Juliana Luna Mora is a lecturer at RMIT School of Fashion and Textiles. Her research interrogates fashion as a global system that shapes the experience and agency of women through ethical consumption products, body-mind practices, lifestyles and experiences. Luna Mora’s most recent publication is ‘The Invisible Corset: Discipline, Control and Surveillance in Contemporary Yogawear’ for the journal Film Fashion and Consumption (2021). DOI: 10.1386/ffc_00032_1 and the article ‘Clean Beauty’ Branding: A Bricolage of Bodily and Spiritual Health, Ancient Wisdom and Ethical Virtue (Art Monthly Australasia Autumn 2021). [email protected]

Jess Berry

Dr Jess Berry is Associate Professor, Design History and Theory. Her research primarily centers around the visual culture of fashion and dress and its interdisciplinary intersections with interior design, architecture, art, new media and film. Berry’s recent publications include Cinematic Style: Fashion, Architecture and Interior Design on Film (Bloomsbury 2022) and House of Fashion: Haute Couture and the Modern Interior (Bloomsbury 2018). [email protected]

Notes

1 Bourdieu, “Haute Couture and Haute Culture,” 135.

2 Ibid., 136.

3 New Boss at Chanel,” New York Times, 34.

4 Bourdieu, “Haute Couture and Haute Culture.”

5 Sherman, The Business of Fashion.

6 Nicoletti, “Heritage and Disruption.”

7 Sherman, The Business of Fashion.

8 Antonaglia and Ducros, “Christian Dior: The Art of Haute Couture,” 136.

9 Ibid., 130.

10 Bourdieu and Delsaut, “Le Couturier et sa Griffe.”

11 Benjamin, “Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century.”

12 Ibid.

13 Evans, Fashion at the Edge.

14 Marx, Capital.

15 Adorno, In Search of Wagner.

16 Evans, Fashion at the Edge, 89.

17 Evans, Fashion at the Edge.

18 Ibid., 99.

19 Benjamin, “Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” 82.

20 Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, 88.

21 Ibid.

22 Harper’s Bazaar, “The Chanel Spirit.”

23 O’Neil, “Ode to Coco.”

24 Vogue, “Chanel: The style and the spirit.”

25 Givhan, “The Era of Elegance,” CO1.

26 Cartner-Morley, “Viard’s Chanel comes into sharper focus.”

27 Viard in Croft, “Virginie Viard on her SS22 Chanel Couture Show.”

28 Bourdieu, “Haute Couture and Haute Culture.”

29 Lagerfeld, “Karl Chats with Coco.”

30 Ibid., 226

31 Ibid., 228.

32 Cited in Socha, “Sarah Burton the Woman behind McQueen.”

33 Amed, “Autumn/Winter Citation2010.”

34 Fox, “Sarah Burton named as Alexander McQueen’s successor.”

35 Horon, “Staying true to the McQueen Spirit.”

36 Frankel, “Alexander McQueen.”

37 Bourdieu, “Haute Couture and Haute Culture,” 134.

38 Alexander McQueen website, “Remembering our friend.”

39 Kapferer and Bastien, The Luxury Strategy; Arnould and Dion, "Fetish, Magic, Marketing."

40 Kaiser et al., Fashion and Cultural Studies.

41 Bourdieu, “Haute Couture and Haute Culture.”

42 Lipovetsky and Roux, El Lujo Eterno.

43 Kapferer and Bastien, The Luxury Strategy.

44 Garelick, Coco Chanel and the Pulse of History.

45 Driscoll, “Chanel: The Order of Things,”143.

46 Cited in Bolton et al. Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, 30.

47 Fox, Alexander McQueen, 152.

48 Evans, Fashion at the Edge.

49 Kaiser et al., Fashion and Cultural Studies.

50 Arnould and Dion, "Fetish, Magic, Marketing."

51 Kovesi, “The Aura of Luxury.”

52 Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

53 Bourdieu and Delsaut, “Le Couturier et sa Griffe.”

54 Ibid., 8.

55 Lipovetsky and Roux, El Lujo Eterno,185.

56 Garelick, “Lagerfeld, Fashion and Cultural Heritage.”

57 Leymarie, Eternal Chanel.

58 Arnaud, Gabrielle Chanel, 197.

59 Leymarie, Eternal Chanel.

60 Lipovetsky and Roux, El Lujo Eterno.

61 McWade, “From Rat to Wraith,” 76.

62 Evans, Fashion at the Edge, 47.

63 Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

64 Evans, Fashion at the Edge, 12.

65 Kapferer, "Why Are We Seduced by Luxury Brands?"; Arnould et al, "Fetish, Magic, Marketing."

66 Arnould et al., "Fetish, Magic, Marketing," 30.

67 Evans “The Enchanted Spectacle.”

68 Arnould et al., "Fetish, Magic, Marketing," 31.

69 Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, 111.

70 McDonald, “Coco Chanel’s manifesto.”

71 Chanel website, “The Stairs.”

72 Cartner-Morley, “Chanel Evokes Ghost of Coco.”

73 Ibid.

74 Benjamin in Hroch, “Fashion and its Revolutions,” 107

75 Hroch, “Fashion and its Revolutions,” 114.

76 McQueen cited in Bolton, Savage Beauty, 73.

77 Cited in Khan, “Fashion as Mythology,” 263.

78 Khan, “Fashion as Mythology,” 261.

79 McWade, “From Rat to Wraith.”

80 Menkes, “McQueen’s Mesmerizing Finale.”

81 Evans, “The Enchanted Spectacle.”

82 Khan, “Fashion as Mythology,” 261.

83 Cited in Mower, “Alexander McQueen Spring 2023 ready-to-Wear.”

84 Evans, Fashion at the Edge,13.

85 Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, 150.

Bibliography

- Adorno, Theodor. In Search of Wagner. Translated by Rodney Livingston. London and New York: Verso, 1981.

- Amed, Imran. “Autumn/Winter 2010: The Season that was.” Business of Fashion. March 17, 2010. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/autumnwinter-2010-the-season-that-was/

- Antonaglia, Federica, and Juliette Passebois Ducros. “Christian Dior: The Art of Haute Couture.” In The Artification of Luxury Fashion Brands, edited by Marta Massi and Alex Turini, 113–139. London: Palgrav, 2020.

- Arnaud, Claude. Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto. London: Thames & Hudson, 2020.

- Arnould, Eric, Cayla Julien, and Delphine Dion. “Fetish, Magic, Marketing.” Anthropology Today 33, no. 2 (2017): 28–32. no. doi:10.1111/1467-8322.12339.

- Baudrillard, Jean. Symbolic Exchange and Death. London: Sage, 2012.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction [1935]. United States: Prism Key Press, 2010.

- Benjamin, Walter. “Paris Capital of the Nineteenth Century [1939].” New Left Review 1, (1968): 77–88.

- Bolton, Andrew, Alexander McQueen, Susannah Frankel, Tim Blanks, and Sølve Sundsbø. Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. “Haute Couture and Haute Culture.” In Sociology in Question. Translated by Richard Nice. London: Sage, 1993.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Yvette Delsaut. “Le Couturier et sa Griffe: Contribution à Une Théorie de la Magie” [the Couturier and His Signature: Contribution to a Theory of Magic].” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 1, Janvier (1975): 7–36. doi:10.3406/arss.1975.2447.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess. “Chanel Evokes Ghost of Coco with 1980s Inspired Collection,” The Guardian. December 5, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2019/dec/04/chanel-coco-collection-virginie-viard

- Cartner-Morley, Jess. “Viard’s Chanel Comes into Sharper Focus with Tribute to Coco,” The Guardian. January 21, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/jan/21/viard-chanel-tribute-coco-lagerfeld

- “Chanel: The Style and the Spirit.” Vogue August (1985): 302–309.

- Croft, Claudia. “Virginie Viard on her SS22 Chanel Couture Show.” March 30, 2022. https://www.10magazine.com.au/articles/virginie-viard-on-her-ss22-chanel-couture-show

- Dion, Delphine, and Eric Arnould. “Retail Luxury Strategy: Assembling Charisma through Art and Magic.” Journal of Retailing 87, no. 4 (2011): 502–520. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2011.09.001.

- Driscoll, Catherine. “Chanel: The Order of Things.” Fashion Theory 14, no. 2 (2010): 135–158. doi:10.2752/175174110X12665093381504.

- Evans, Caroline. “The Enchanted Spectacle.” Fashion Theory 5, no. 3 (2001): 271–310. doi:10.2752/136270401778960865.

- Evans, Caroline. Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Fox, Chloe. Alexander McQueen. London: Quadrille, 2012.

- Fox, Imogen. “Sarah Burton Named as Alexander McQueen’s Successor,” The Guardian. May 2, 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/may/27/sarah-burton-alexander-mcqueen-gucci

- Frankel, Sussanah. “Alexander McQueen: The Bull in a Fashion Shop,” The Guardian. October 15, 1996. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2020/oct/15/alexander-mcqueen-bull-in-a-fashion-shop-fashion-archive-1996

- Garelick, Rhonda. “Lagerfeld, Fashion and Cultural Heritage.” English Language Notes 60, no. 2 (2022): 156–174. doi:10.1215/00138282-9890835.

- Garelick, Rhonda. Mademoiselle: Coco Chanel and the Pulse of History. Sydney: Pan MacMillan, 2014.

- Givhan, Robin. “The Era of Elegance: Karl Lagerfeld Beautifully Channels the Spirit of Chanel.” Washington Post, March 14, 1998. CO1.

- Horon, Cathy. “Staying True to the McQueen Spirit,” The Cut. March 16, 2022. https://www.thecut.com/2022/03/staying-true-to-alexander-mcqueens-spirit.html

- Hroch, Petra. “Fashion and Its Revolutions in Walter Benjamin’s Arcades.” In Walter Benjamin and the Aesthetics of Change, edited by Anca M. Pusca, 108–126. London: Palgrave McMillan, 2010.

- Kapferer, Jean-Noël, and Vincent Bastien. The Luxury Strategy. 2nd ed. London: Kogan Page, 2012.

- Kapferer, Jean-Noël. “Why Are We Seduced by Luxury Brands?” Journal of Brand Management 6, no. 1 (1998): 44–49. doi:10.1057/bm.1998.43.

- Kaiser, Susan B., and Denise N. Green. Fashion and Cultural Studies. London: Bloomsbury, 2022.

- Khan, Nathalie. “Fashion as Mythology – Considerations on the Legacy of Alexander McQueen.” In Fashion Cultures Revisited: Theories, Explorations and Analysis, edited by Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson, 261–271. Routledge: London, 2013.

- Kovesi, Catherine. “The Aura of Luxury: Cultivating the Believing Faithful from the Age of Saints to the Age of Luxury Brands.” Luxury 3, no. 1-2 (2016): 105–122. doi:10.1080/20511817.2016.1232468.

- Lagerfeld, Karl. “Karl Chats with Coco.” Harper’s Bazaar, March 2003. 226–229.

- Leymarie, Jean. Eternal Chanel: An Icon’s Inspiration. London: Thames & Hudson, 2010.

- Lipovetsky, Gilles, and Elyette Roux. El Lujo Eterno, De la Era de lo Sagrado al Tiempo de las Marcas. [Eternal Luxury, from Sacred Times to Brand Times]. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama, 2004.

- Marx, Carl. Capital, Vol. 1, Translated by Ben Fowkes, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1976.

- McDonald, John. “Coco Chanel’s Manifesto Shows a Woman of Style with Substance” The Sydney Morning Herald. February 4, 2022. https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/coco-chanel-s-manifesto-shows-a-woman-of-style-with-substance-20220127-p59rq9.html

- McWade, Chris. “From Rat to Wraith: Spectral Transgression against Masculine Tropes in Alexander McQueen’s EclectDissect (a/W for Givenchy 1997–1998).” Fashion Theory 25, no. 1 (2021): 75–98. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2019.1598203.

- Menkes, Susy. “McQueen’s Mesmerizing Finale.” The New York Times. March 9, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/10/fashion/10iht-rmcq.html

- Mower, Sarah. “Alexander McQueen Spring 2023 Ready-to-Wear.” Vogue Runway. October 11, 2022. https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/spring-2023-ready-to-wear/alexander-mcqueen

- “New Boss at Chanel.” New York Times, Feb 17 1971. 34. https://nytimes.com/1971/02/17/archives/new-boss-at-chanel.html

- Nicoletti, Susanna. “Heritage and Disruption Rule in Luxury, but is there a Third Path to Success,” Luxury Society. November 11, 2019. https://luxurysociety.com/en/articles/2019/11/opinion-heritage-and-disruption-rule-luxury-there-third-path-success

- O’Neil, Kristina. “Ode to Coco: Karl Lagerfeld on the Mystique of Chanel” Harper’s Bazaar, April 2005. 200–207.

- “Remembering our Friend, Mentor and the Founder of this house, Lee Alexander McQueen.” Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.alexandermcqueen.com/en-au/stories-article2

- Sherman, Lauren. “Succession Planning: What Works What Doesn’t.” The Business of Fashion. March 20, 2019. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/succession-planning-what-works-what-doesnt/

- Socha, Miles. ‘Sarah Burton the Woman Behind McQueen.’ Women’s Wear Daily. May 27, 2010. https://wwd.com/fashion-news/designer-luxury/sarah-burton-the-woman-behind-mcqueen-3308855/

- “The Chanel Spirit.” Harper’s Bazaar, November 1985. 208–209.

- “The Stairs.” Chanel News. January 25, 2016. https://www.chanel.com/au/fashion/news/2016/01/the-stairs.html)