ABSTRACT

In the early twentieth century, European criminal justice systems started to discuss new security measures for dealing with persistent habitual criminals and mentally disordered offenders. New preventive institutions were established in the Nordics in the shift of the 1920–1930s. Indeterminate confinement came to cover both persistent property offenders, and repeat serious violent and sexual offenders. The success of these measures and the effectiveness of institutional treatment more generally, came to be questioned in the Nordic countries in the 1960s and 1970s. Disappointment about treatment effectiveness, combined with increased stress on legal safeguards, predictability and proportionality in the administration of criminal justice, undermined professional support for indeterminate sanctions and compulsory care. The use of preventive detention was either restricted, as in Denmark and Norway, or abolished altogether, as in Finland and Sweden. However, there were other arrangements in the latter countries, which partly served the same purpose.

I. Historical outlook: the rise and fall of preventive detention in the Nordics

A. The adoption and expansion of preventive detention

In the policy shifts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Nordic countries followed the continental European trends closely. The First International Penitentiary Congress was held in 1872 in London, the next one in Stockholm in 1879, and after that in five intervals held across Europe. The Nordic countries were involved in this co-operation from the beginning. One of the recurring themes in these meetings was the treatment of habitual criminals. Solutions offered by the mid-1800s German classical school of criminal law, were contested by indeterminate sanctions proposed by the emerging sociological and positivist schools in Germany (Franz von Liszt) and Italy (Enrico Ferri), propagated by the Internationalist Criminalist Association.Footnote1

Legislative proposals for protective measures were first put forward in Norway in 1893 by Bernhard Geztz, an active member of the von Liszt circle. Norway was also the first Nordic country to include a ‘second track’ of indeterminate sanctions in its criminal law. This took place with the enactment of a new Norwegian Criminal Code in 1902 (the most modern Criminal Code at that time and much inspired by the ideas of the German sociological school). In 1929, two forms of preventive detention were established. ‘Forvaring’ was reserved for repeat offenders for whom a normal prison sentence was not deemed secure enough; ‘sikring’ was reserved for offenders with diminished or no criminal responsibility due to mental disorders, with a risk of reoffending. Conceptually, sikring was not regarded as a criminal sanction.Footnote2

Sweden adopted ‘internering’ for repeat offenders in 1927. Offenders with diminished responsibility due to mental disorders could be placed under indeterminate ‘forvaring’ (corresponding to sikring in Norway; the terms have been used in various Nordic countries without any obvious consistency). The use of internering for recidivists declined by the mid-1930s to close to zero. The scope of forvaring, in turn, was extended to less serious offences and the threshold for criminal liability was lowered to enable psychopaths to be placed under forvaring. As a result, the annual admissions to forvaring increased from around 20–30 in the late 1920s to 80–100 by the late 1940s.Footnote3

The need for indeterminate sanctions was discussed in Denmark in the early 1920s, but reforms were delayed pending the general reform of the Criminal Code. Pressures created by one repeat sexual offender, however, forced the Danish legislature to draft a special law on internering in 1925. These provisions were replaced by the new Criminal Code in 1930 with two forms of secure confinement. ‘Psykopatforvaring’ (subsequently called forvaring) was reserved for mentally abnormal offenders, and sikkerhedsforvaring for habitual high-risk offenders.Footnote4 The former was provided in a special institute, the Herstedvester, which became world famous for its treatment methods.

Finland conducted similar reforms in 1931. Due to a lack of resources, however, the treatment-oriented alternative for the mentally ill was dropped. Compared to a normal prison sentence, the main difference was the possibility of prolonging the confinement of high-risk offenders beyond the originally pronounced sentence.

Thus the laws generally distinguished between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ offenders. The former were subjected to longer prison sentences, while treatment was also provided for the latter. In practice, however, the difference may not have been so substantial.

‘Abnormal’ offenders were further divided into those lacking all penal capacity, and those with only diminished criminal responsibility. Non-responsible offenders were released from all criminal liability, but were usually placed under mental health care. Offenders with diminished responsibility could be sentenced – depending on the country – either to criminal punishment or to some specific measure, or both. There were also differences between the Nordic countries. The treatment ideology was stronger in countries with more welfare resources, particularly Sweden. Corresponding institutions established in Finland mainly provided prolonged confinement, and much less (if any) psychiatric treatment.

The heyday of these institutions was the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Of the original two tracks of the system – one for normal offenders, the other for abnormal – the latter proved to be more popular ().

Table 1. Peak years of preventive detention in the Nordic countries.

B. Criticism and reforms of indeterminate sanctions (1960s and 1970s)

The first critical voices against overly long confinement periods for trivial offences were heard in the 1950s. In the course of the 1960s, this criticism coalesced with general criticism of all forms of institutional treatment. All Nordic countries experienced a period of penal liberalisation during the 1970s, following a decade-long public and professional criticism of the general use of various forms of compulsory institutional confinement, whether it be in prisons, reform schools, reformatories for alcohol misuse, mental hospitals or specific institutions for mentally disordered offenders.Footnote5

The discussions took somewhat divergent courses in the Nordic countries, as both the penal and social welfare practices varied locally. The first reforms to realise these aims were implemented in social welfare, mental health care, and child protection in the 1960s, with criminal justice reforms following during the 1970s. These reforms, carried out mainly in the 1960–1970s, fully realised the principles that became characterised in Finland as the ‘humane and rational criminal policy’.Footnote6 This period resulted in several major human rights-oriented improvements in sentence enforcement, including de-penalisation and general humanisation of sentence enforcement and prison conditions (especially in Finland), the expansion of open prison regimes and the adoption of prison leave in all Nordic countries, as well as the abolishment or restrictions of all indeterminate sanctions.

The scepticism towards penal rehabilitation leads to a reformulation of enforcement aims and principles. In order to counteract ‘prisonization’ the enforcement reforms of the 1970s stressed the normality principle; the idea that conditions and daily routines in prison should be organised in a manner that as far as possible reflects society outside the walls.Footnote7 Ambitious rehabilitative aspirations were downscaled to more (realistic) attempts to organise the enforcement in a manner that minimised the (unavoidable) harms resulting from the deprivation of liberty (the principle of harm minimisation). And in order to secure predictability and equality, discretionary release rules were replaced with fixed semi-automatic practices.

In this debate, special attention was paid to preventive detention, for it exemplified the three major flaws in the prevailing penological practices: (1) unfounded trust in the effectiveness of institutional treatment; (2) unjustified severe penal sanctions imposed under the false flag of treatment and rehabilitation and (3) inhumanity caused by the indeterminate nature of the sanction. Consequently, a substantial part of the social-liberal critique of the penal system in the 1960s and 1970s was focused on preventive detention and compulsory mental health care.Footnote8

1. Finland and Denmark restrict the use of preventive detention

Criticism of coercive care and overuse of penal custody was loudest in Finland, largely because of the country’s exceptionally high incarceration rates. Finland was also the first to renew the legal structures of secure detention. In 1971, it restricted the application of the system to repeat serious violent offenders only. The reform had a dramatic effect: the number of prisoners held in preventive detention decreased virtually overnight from 250 to below 10. The law still allowed for prolonged incarceration beyond the original sentence on preventive grounds. However, since 1971 no-one has been held in prison beyond the originally imposed prison term.Footnote9

Danish institutions for secure confinement had been criticised from the mid-1960s. In 1967, the Danish Criminal Law Commission instigated the first major effectiveness analyses of legal sanctions. No differences in re-offending rates were found between treated and non-treated offenders, which led the Commission to propose severe restrictions on the use of indeterminate confinement.Footnote10 Legislative changes appeared later. In 1973, the forvaring provisions were revised. Security confinement was abolished altogether, and the scope of forvaring was restricted to serious repeat violent offenders. Even before these changes, the use of specific institutions and indeterminate sanctions had been scaled down in practice.

2. Sweden abolishes preventive detention

Reform in Sweden took place in two phases. The 1962 reform of the Swedish Criminal Code (brottsbalk) followed the still prevailing treatment ideology. The law combined forvaring and internering into a single measure, this time under the label ‘internering’. The measure was applicable under certain conditions to all repeat violent offenders who were sentenced to imprisonment of at least two years.

The 1962 brottsbalk also brought another, much more radical change. It abolished the concept of criminal responsibility altogether. Everyone was, in a sense, responsible. But the mentally ill could not be sent to prison. Instead, they were sentenced to forensic care. Under the new Swedish law, mental treatment could also be defined as a punishment.

However, during the enactment of the brottsbalk, criminal policy thinking was already taking another turn. In fact, the year the new brottsbalk came into force (1965) marked the culmination of the implementation of indeterminate sanctions in Sweden. The annually imposed detention orders (for offenders sentenced to this sanction for the first time) declined from 150 in the mid-1960s to around 30 in the mid-1970s, while the number of offenders in secure detention fell from 600 in 1965 to 150 in the late 1970s. After this, criticisms became louder as the other Nordic countries abolished or restricted the application of preventive detention. Internering was finally abolished in 1981.

However, to compensate for this mitigation, penalties for serious violent recidivism were increased. In addition, there is an indication that the use of life sentences increased after the abolition of internering: between 1970 and 1979 the courts imposed 11 life sentences, and between 1980 and1989 the figure had tripled to 37.Footnote11

3. Norway abolishes life sentences

Forvaring was popular in Norway in the 1930s. However, its popularity declined through the 1950s and 1960s, and the last forvaring order was handed down in 1963. Sikring, in turn, was reserved for both non-responsible offenders and those with diminished criminal responsibility. During the 1950 and 1960s, the annual number of orders was around 100.

The use of sikring and the double-track system generally had been criticised during the 1950s, but this criticism increased during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The annual number of orders also fell to around 20. In 1973, it was proposed to restrict the use of indeterminate penal measures and to remove the mentally ill from prison to psychiatric institutions. The proposals were criticised both by those who wished to abolish indeterminate measures altogether, as well as by psychiatrists who saw the reform as intruding too greatly on their own discipline.Footnote12 As a consequence, Norway never actually reformed preventive detention. However, in practice, the use of this alternative was restricted to a minimum in the late 1970s and 1980s.

The logical conclusion following from the critique of indeterminate sanctions was the abolition of life imprisonment. This option was discussed in the Nordic countries in the 1970s, but only Norway took these considerations to their logical conclusion. In 1981, Norway abolished life imprisonment with reference to both the principle of humanity and legal safeguards. The government wrote in its proposal: ‘Taken literally, life imprisonment is not compatible with our conception of humanity’. And even if the sentence was not applied in a literal sense, the indeterminate nature of confinement, as well as the extra stigma related to life imprisonment that would have ‘socially exclusionary effects’ were seen to be reasons strong enough to justify the abolition of life sentences.Footnote13 This reform may be characterised as one of the last major reforms carried out in the spirit of liberal reform based on the critique of indeterminate sanctions in the 1960 and 1970s.

The abolition of life imprisonment was not meant to lead to changes in the existing penal practice. To achieve this, the legislator increased the existing maximum length of a prison term from 15 to 21 years. The idea was that increased maximums, together with the application of the parole rules, should lead to the same results as before the law reform.Footnote14

II. Establishing the present system

As the systems stand today, two countries – Denmark and Norway – have retained preventive detention and the possibility of prolonged indeterminate confinement. Finland has replaced preventive detention by a system that restricts the early release of high-risk violent offenders. Sweden has abolished this option altogether (but provides for indefinite confinement as a criminal sanction in the form psychiatric care orders). This section gives an overview of legislation and recent practices in the implementation of these alternatives.

A. Forvaring in Norway (total reform 1997–2002)

The current Norwegian law on preventive detention is the product of a drawn out process. The 1973 proposal was never accepted.Footnote15 A new proposal was put forward in 1990, accepted in 1997 and entered into force in 2002. The reform followed the lines already set out in 1973, with minor amendments.Footnote16 Both sikring and the double-track system were abolished. The 2002 reform replaced the old system of sikring with three new measures, depending partly on the degree of responsibility: persons who were not criminally responsible could be placed under two forms of compulsory psychiatric care orders depending on the nature of their mental disorder. Thirdly, forvaring required total or partial (diminished) criminal responsibility, and was also defined as a sanction in the Criminal Code. The Norwegian parliament enacted a new Criminal Code in 2005 but the Code entered into force only on 1 October 2015. While the main structure of forvaring remained intact, there were some detailed changes.Footnote17

Forvaring is the most severe sanction under Norwegian law. It is applicable ‘when a sentence for a specific term is deemed to be insufficient to protect life, health or freedom of others’.Footnote18 The conditions are defined separately for more serious and less serious offences in Article 40 of the Criminal Code. For more serious offences it is required that (1) the offender has been convicted of a serious violent felony, sexual felony, unlawful deprivation of liberty, arson or other serious felony impairing the life, health or liberty of other persons, and (2) there is an imminent risk that the offender will again commit such a felony. Forvaring is also applicable for less serious felonies of the same nature as specified above, (1) if the offender has previously committed or attempted to commit a felony as specified, (2) there is a close connection between the previous felony and the one now committed and (3) the risk of relapsing into a new felony must be deemed to be particularly imminent. Thus, for more serious offences, forvaring is possible after a first conviction and with a lower re-offending risk, compared to less serious offences. Under the most recent law reform the imposition of forvaring on young offenders was restricted by requiring that offenders under 18 years of age be placed under forvaring only if ‘totally extraordinary reasons’ call for the application of the sanction.

In assessing the risk of re-offending, the crime committed or attempted must be considered, as well as the offender's conduct and capacity to function in society. In the case of less serious offences, particular weight shall be given to whether the offender has previously committed or attempted to commit a similar type of felony.

Before forvaring can be pronounced, a social inquiry must be conducted into the person charged. The court may instead decide that the person charged shall be subjected to a forensic psychiatric inquiry.

The law sets initial limits on the duration of forvaring. The court must specify a term that should usually not exceed 15 years and may not exceed 21 years. For offences with a specific maximum of 30 years (terrorism), the upper limit of forvaring is also 30 years. The maximum term may, however, be extended, on the application of the prosecutor, for up to five years at a time.

A minimum period must also be determined. This term may not exceed 10 years. However, in cases involving offences with a maximum sentence of over 15 years, the upper limit for the minimum is 14 years. In cases with a maximum of over 21 years, the upper limit of the minimum period is 20 years (Criminal Code, Article 43).

Prisoners subject to forvaring are released on probation for a period of between one and five years, at the request of the convicted person or the prison and probation services. If the prosecutor agrees, the release decision can be taken by the prison and probation services. If the prosecutor does not agree, the prosecuting authority shall submit the case to the District Court, which will make a judgment. Probation can be granted with conditions similar to those of a conditional sentence. The court may also impose a condition to the effect that the convicted person shall be followed up by the correctional services. The convicted person shall be allowed to express his views on the conditions beforehand. Should probation be denied, the convicted person has a right to make a new application once a year.

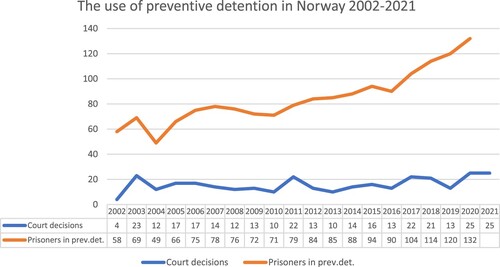

displays the trends in the use of forvaring in Norway 2002–2021. The annual number of court orders remained has fairly stable ranging from 15 to 20. However, during the last 10 years the daily number of prisoners in preventive detention has almost doubled from the level of 80 to 130. Specific analyses for the years 2002–2013 show that half of the orders were for sexual offences (49%); homicide and attempted homicide cover about one quarter, while the rest were divided between assault (15%), robbery (5%), arson (6%) and others (1%; see Johnsen and Engbo 2015: 180).Footnote19 During the last 10 years (2012–2022) the courts have imposed in average 17.2 forvaring-orders while the daily number of inmates in preventive detention has been 101.2. Corresponding figures for the year 2002–2011 were 14.4 and 69.3.

Figure 1. Preventive Detention in Norway: 2002–2021. Source: Compiled from Statistics Norway, Kristoffersen 2016 and 2022.

In general, prisoners subject to forvaring are housed in three high-security prisons that are also able to provide comprehensive psychiatric treatment: Ila, Trondheim and Bredveit (for women). In 2013, there were 85 prisoners subject to forvaring (annual average). The law requires intense rehabilitation efforts for forvaring prisoners, but in practice the prison routines are similar to other prisoner groups. The Norwegian prison authorities describe the aims of forvaring as follows:

The aim of preventive detention is that the offender will change his or her behaviour and adapt to a law-abiding life. The contents of a sentence of preventive detention are designed with the offender’s possibilities for development in this direction in mind, and will as much as possible be adjusted to the individual’s specific needs. It is based on cross-professional collaboration and wards for preventive detention that have access to more resources than general high-security wards.Footnote20

Prisoners in forvaring may apply for prison leave, permission to work outside the prison and release on probation, as other groups may. However, there are different time limits, and these applications are usually granted only after two-thirds of the sentence has been served. Three out of four prisoners have been granted prison leave before release on probation. The prisoner may be transferred to a lower security prison, but not before two-thirds of the sentence has been served.

In 2011, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) conducted a visit to Ila prison, which holds the majority of offenders under preventive detention. The conclusions of the Committee were generally positive, stating that it had gained a ‘favourable impression of the activities offered to all persons in preventive detention’, including a range of structured offending behaviour programmes.Footnote21 The UN Committee Against Torture has also examined forvaring and concluded that Norway ‘should revise its system of preventive detention, reducing its use to an absolute minimum’.Footnote22

B. Forvaring in Denmark (partial reforms 1997–2002)

Since the 1970s reform, there have been two minor changes to the Danish system. In 1997, the threshold for forvaring was lowered for sexual offences (as a reaction to one particular case). In 2002, maximum time limits were set for care orders for offenders placed under compulsory care. This was motivated mainly by the fact that in many cases offenders found guilty of non-violent offences had been placed under disproportionately long care orders.Footnote23

Forvaring, as defined in Article 70 of the Criminal Code, is an indeterminate sanction for high-risk violent offenders. It is classified as a ‘measure’ (foranstaltning), not as a punishment, which may be imposed on both criminally responsible and non-responsible offenders. Preconditions defined in the law distinguish between violent and sexual offences. In both cases, the criteria fall into three parts: those related to the (1) seriousness of the offence, (2) the risk of re-offending and (3) the requirement of necessity.

Offenders found guilty for any of the listed violent offences (including homicide, robbery, a serious crime of violence, and arson), may be placed under forvaring if ‘it is apparent from the nature of the act that has been committed and from the information available concerning his character, with special reference to his criminal record, that he poses an immediate danger to the life, body, health or liberty of others’ and if ‘the use of safe custody, in place of imprisonment, is considered necessary to avert this danger’ (Criminal Code, Article 70). Offenders found guilty of rape ‘or any other serious sexual offence or attempting such an act’, may be placed on forvaring under the same conditions if they pose an ‘essential immediate danger’ to the life, body, health or liberty of others. The difference between violent and sexual offences relates to the risk of future crimes. For violent offences it is required that there be an ‘immediate’ (naerligende) danger, while for sexual offences it is enough that the risk be ‘essential (vaesentlig).

There are no specific minimum or maximum time limits for forvaring. However, the prosecutor is obliged to ensure that the confinement does not last longer than needed. To ensure this, there are specific rules and procedures. Release and termination of confinement is decided by the court. The offender or the placement unit may request the prosecutor to take the case to court. If the court decides to continue the confinement, a new request may be made after six months. Once the confinement has lasted three years, the placement unit is obliged to draw the matter to the prosecutor annually.

The release process from Danish forvaring follows the same stepwise model as with other prison sentences. The prisoner is allowed normal prison leave, but the first escorted prison leave takes place only after four to five years detention (and non-escorted after eight to ten years detention). Prisoners are usually released on probation, and no formal probation period is fixed. The final termination of forvaring takes place following a court decision, usually after a year of a problem-free probation period. However, probation periods may also last much longer.

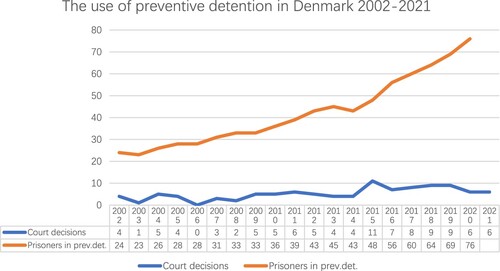

The number of offenders in preventive detention has also been steadily increasing in Denmark from 25 individuals in 2002 to over 40 in 2013. displays the trends in the use of forvaring in Denmark 2002–2021. The annual number of court orders has slowly increased from the level around 5 to around 10. The daily number of prisoners in preventive detention has more than doubled from the lkevel os 25–30 to over 70. Like Norway, half of the orders were for sexual offences (49%). Assault covers 25%, homicide and attempted homicide 12% and the rest is divided between arson (7%), robbery (5%) and other (3%).

Figure 2. Preventive Detention in Denmark: 2002–2021. Source: Compiled from Statistics Denmark, Kristoffersen 2014 and 2021.

The periods of imprisonment under forvaring are long, and they have become longer. In the early 1990s, the mean duration of confinement before release on parole was a little over seven years. Between 2005 and 2009, this period had doubled to 14 years. Placement in a half-way house takes place after 11–12 years and release on probation after 14 years (see Anstalten ved Herstedverster 2012).

All offenders subject to preventive detention are placed in the Herstedvester Institution (originally established in 1935 as a ‘psychopath institute’ under the law reforms in the 1930s). Prisoners serving life sentences are also placed in this institution, as well as long-term prisoners in need of specific psychiatric care. In the beginning of 2012, there were 150 prisoners in total, 29 of whom were under forvaring. Twelve were serving life sentences and 90 were serving determinate prison sentences.Footnote24

One specific group of offenders in this institution are sex offenders undergoing anti-hormone therapy. Combined with psychotherapy, the libido-suppressing treatment is intended to prevent the offender from having compulsive and violent sexual fantasies, so as to prevent re-offending. The criteria for such treatment are threefold: (1) the offenders have committed repeated or very serious sexual offences; (2) they are deemed to be at risk of relapsing into the same type of offences and (3) they are assessed as persons for whom psychotherapy and other forms of treatment cannot reduce the risk of re-offending. An individual’s consent is a pre-condition for the treatment. All cases requiring libido-suppressing treatment as a condition of release are submitted to the Medico-Legal Council for approval (an independent body assessing the need for psychotherapeutic treatment). Annually, two to four inmates commence this treatment.

The CPT has conducted several visits to the Herstedvester Institution, the last one taking place in 2008. During these visits the Committee has paid specific attention to sexual offenders undergoing anti-hormone therapy, and to the situation of prisoners from Greenland. The Committee has expressed the need to ensure that patients’ consent to medical treatment is genuinely free and informed.Footnote25 The prisoners must be given a detailed explanation (oral and written) of all recognised adverse effects (as well as benefits) of the drugs concerned. Moreover, in addition to drug treatment, efforts should be made to provide psychotherapy and counselling with a view to reducing the risk of reoffending. The CPT concluded that ‘medical libido-suppressing treatment of sex offenders is at present surrounded by appropriate safeguards’, but the committee also considered that ‘more attention should be paid to ensuring that these safeguards are being fully respected in practice … that prisoners’ consent to medical libido-suppressing treatment is genuinely free and informed … the provision of full information (oral and written) on the known adverse effects – as well as the possible benefits – of the treatment, should be improved’ and that ‘no prisoner should be put under undue pressure to accept medical libido-suppressing treatment’.Footnote26

C. Finland – two reforms 2006 and 2016

1. Serving the sentence ‘in full’ and the abolishment of early release (2006)

Next reform took place in connection on the total reform of Finnish prison law in 2006. Even a theoretical possibility that someone could be held in custody longer that the pronounced sentence was considered as embarrassing and problematic from the point of Human Rights and Rule of Law. To end this practice, preventive detention was abolished and replaced by a system that enabled the courts to order serious violent offenders to serve their sentence ‘in full’, without the option of normal parole.

However, also prisoner serving the ‘full’ sentenced were allowed to be released on electronically supervised liberty 3–6 months before the end of the sentence. The principal difference to the previous practice was that no-one could be kept in custody longer that the original sentence, not even in theory.

This new option was reserved for the same category of high-risk violent recidivists who would have been subject to the earlier preventive detention. Possible offenses – to this option – were listed in the law as previously. The offender had also to have a previous criminal history of similar offenses during the past 10 years. Thirdly, on the basis of the present and past offenses the offender was considered to be ‘particularly dangerous to the life, health or freedom of another’.

This new option was also meant to be used in an equally restrictive manner as was the earlier system of preventive detention. In practice the daily number of prisoners serving their sentence in full rose for the previous level of around 20 to a little over 30. Indicating 1–3 new cases/year.

2. New combination sentence with community supervision (2017)

Serving the sentence in full meant that violent offenders were released either to ‘supervised liberty’ 3–6 months before the end of the sentence, or without any supervision after the full completion of the sentence (which became quite common). Having hight-risk offenders released without any support of supervision caused justified concerns, and a working group was set up to prepare solutions in the mid-2010s.

This work led to a law-reform in 2017. A new sanction, ‘Combined Sentence’ was enacted. This meant in fact, that a separate one-year supervision period was added to the original sentence. This period consisted of both support and supervision. The supervision takes place in the form of electronic monitoring which had been implemented from the 2006 onwards as apart of post-release supervision.

Otherwise, preconditions for the use of the new sanction remained more or less the same as before. (1) The offender has to be sentenced to at least three years determinate prison term for an offense listed in in the law (covering in practice all forms of intentional lethal violence, serious sexual offenses and crime against humanity). (2) He/she has been found guilty during the preceding 10 years for a similar offense. (3) Based on a separate examination the offender is deemed to be ‘particularly dangerous to the life, health or freedom of another’. Each case has to pass a careful risk-assessment, conducted by a multi-professional team (and with the help of the latest prediction-tools), as well as a specific examination on the mental capacity of the suspect. The assessment process lasts for several weeks.Footnote27

As regards the enforcement of prison term, general rules apply. There is no ‘specific regime’ for offenders sentenced to combination sentence. The aims of enforcement and routines are no different from ordinary prison sentences. For all prisoners, an individual sentence plan will be drafted.Footnote28 The plan is based on a structured risk and needs assessment and is the backbone of the sanction during the whole prison term. It has information on the personal needs and abilities of the prisoner, the required level of security and a preliminary plan for release. The sentence plan also forms the foundation for the placement of the prisoner in a prison corresponding to his/her circumstances and the level of security required.

Supervision period is regulated in detail by the law and for each person a detailed supervision plan is drafted. The offender is obliged to remain under electronic monitoring and allowed to leave the house only during period defined in the individual sentence plan. He/she is also obliged to participate in programme activities and supervisory meeting as defined in the plan, and not to use drugs during the enforcement. If these conditions are breached, the rest of the supervision time may be converted to imprisonment.

New provisions have been implemented since 2018. In 2018–2021 in all 23 persons have been sentenced to combination sentence. Out of these 18 have been found guilty of homicide.

III. Discussion

Each legal system has developed in order to minimise the risks of most serious offenses and high-risk violent offenders. Preventive detention is one of these instruments. Other closely related arrangements in the Nordic countries that serve partly the same purposes are life imprisonment (and release from life imprisonment) and compulsory mental health care orders. Reoffending risks may have a role also in early release practices and sentencing more generally. The functions of these different institutions are coordinated differently in each Nordic country. Restricted use of preventive detention (or the absence of preventive detention as in Finland and Sweden) may be compensated by more extensive use of compulsory mental health care or life imprisonment. And, restrictive use of life imprisonment (or the absence of life imprisonment as in Norway), by more extensive use of preventive detention or compulsory care. The role of and the coordination of these different institutions in the Nordics is analysed in more detail in Lappi-Seppälä’s paper.Footnote29

As regards especially Finland, the law does to recognise ‘preventive detention’ in the traditional sense as a security measure imposed for the offender beyond the ‘regular punishment’. The quite sparingly used Combination Sentence in Finland contains elements towards that direction, but only in the form of determinate period on supervision in the community. This restrictive position of the Finnish criminal justice is based on a sentencing structure which takes the requirements of the Rule of Law and the principles of proportionality and predictability seriously. This, however, is not to deny the value of risk-analyses in the enforcement-level, for example in the drafting the individual sentence plan for the offender to be followed during the enforcement period and as a part of the rehabilitation process.

But beyond that, there is no research-based indication that we are in a better position as we were decades ago, when it comes to the possibility of predicting future violent behaviour in individual level with the help of specific assessment tools. Prediction methods used in the Nordic countries all of the ‘State of the Art.Footnote30 However, the initial problems of legal insecurities when incarcerating offenders on the basis of their estimated future behaviour, still remain. Serious violent behaviour is highly context-determined and guided by factors that cannot be captured in the prediction instruments. When using predictions, the group of so-called False Positives – those who have been predicted as dangerous, but which in face would not have been recidivated comes easily too large to be accepted in system that rule requires full proof – guilt beyond reasonable doubt – before anyone can be sentenced. As phrased by Michael Tonry – after reviewing the most recent literature – ‘predictive sentencing can thus be justified neither empirically nor morally’. But at the same time ‘to many people predictive sentencing … is intuitively plausible. It provides supporters opportunity to express sympathy towards hypothetical future victims and express disdain for people believed to be violent’.Footnote31 In other words, there remains a constant tension between every-day political wishes to select (and confine) beforehand those offenders that are assumed to commit serious offenses in the future, and a research based principled criminal law theory that wishes to put limits to those aspirations in a manner that respects the basic requirements of legal security, culpability and proportionality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 J Hamel, ‘International Union of Criminal Law’ (1912) Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 22.

2 T Lappi-Seppälä, ‘Life Imprisonment and Related Institutions in the Nordic Countries’ in D van Zyle Smti and C. Appleton(eds), Life Imprisonment and Human Rights (Hart Publishing) 465–505.

3 Statens offentliga utredningar (SOU), ‘Skyddslag. Statens offentliga utredningar’ (Committee Report no 55, Statens offentliga utredningar,1956).

4 Greve, V., Straffene (2nd edn, Jurist-og Økonomforbundets Forlag 2002).

5 T Lappi-Seppälä, ‘Nordic Youth Justice: Juvenile Sanctions in Four Nordic Countries’ in M Tonry and T Lappi-Seppälä (eds), Crime and Justice in Scandinavia: A Review of Research (vol. 40, University of Chicago Press, 2011).

6 T Lappi-Seppälä, ‘Nordic Sentencing’ in M Tonry (ed), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research (vol. 45, University of Chicago Press, 2016).

7 See European Prison Rules 2006, s 5.

8 Torsten Eriksson, Kriminalvård Idéer och experiment (Thule, 1967); I Anttila, ‘Incarceration for Crimes Never Committed’ Report of the National Research Institute of Legal Policy no. 9 (National Research Institute of Legal Policy 1975).

9 T Lapi-Sepällä and M Lehti, ‘Cross-Comparative Perspectives on Global Homicide Trends’ in M Tonry (ed), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research (vol. 43,University of Chicago Press 2015).

10 Straffelovrådet, ‘Betænkning om de strafferetlige særforanstaltninger’ (Betænkning nr 667, Straffelovrådet 1972) 309.

11 See also .

12 J Andenaes, M Matningsdal, and G Rieber-Moghn, Alminnelig strafferett (5th edn, Universitetforlaget 2004) 499.

13 Justis- og politidepartementet, Om kriminalpolitiken (Justis- og politidepartementet 1978) 123.

14 Ot.prp. nr. 62 (Om lov om endringer i straffeloven mm., 1980–1981), 31–32.

15 ibid.

16 B Johnsen, ‘Forvaring – fra saerreaksjon og “straff” til lovens strengeste straff: Ett skritt frem eller tilbake?’ (2011) Nordisk Tidskrift for Kriminalvidenskab 2.

17 Both the old and the new Code define forvaring as a criminal punishment (while the old Code listed forvaring together with other ‘special measures’). See Johnsen (n 16) 3–5.

18 Norwegian Criminal Code, s 40.

19 B Johnsen and H Engbo, ‘Forvaring i Norge, Danmark og Grönland – noen likheter og ulikheter’ (2015) Nordisk Tidskrift for Kriminalvidenskap 175.

20 Kriminalomsorgen ‘Preventive Detention’ (Factsheet, 20 February 2016) <http://www.kriminalomsorgen.no/publikasjoner.242465.no.html> accessed 11 March 2016.

21 European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, ‘Report to the Government of Denmark on the visit to Denmark carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 11 to 20 February 2008’ (CPT/Inf, 2008) 61.

22 The Committee also criticised the possibility of placing minors between 15 and 18 years of age in preventive detention and recommended restricting this possibility to exceptional and extraordinary cases according to specific and strict criteria defined by law. As noted above, this restriction was implemented by the law reform of 2015. See ‘UN Committee against Torture’ (2012) para 9.

23 V Greve,J Asbjorn,. and N Toftegaard, Kommentaret straffelov (8th edn, Kobenhavn, Jurist- og Okonomsforbundets Forlag 2005) 327.

24 In addition, there were 19 offenders from Greenland placed under forvaring. See Anstalten ved Herstedverster, ‘Fakta om indsatte’ (2012) <http://www.anstaltenvedherstedvester.dk/Fakta-om-indsatte-2329.aspx> accessed 11 March 2016.

25 See CPT (n 21) 78.

26 Ibid.

27 M Tolvanen, A Keski-Valkama, T Koskela, J Pajuoja, M Rautanen, J Tiihonen, S Tyni, M Törölä, and E Eskelinen, Vaarallisuuden ja väkivaltariskin arvioiminen (VNK 2021)70.

28 For enforcement practices, see ST Lappi-Seppälä, ‘Prisoner resettlement in Finland’ in F Dünkel, I Pruin, A Storgaard, and J Weber (eds.), Prisoner resettlement in Europe (Routledge 2018).

29 Lappi-Seppälä (n 2).

30 Tolvanen (n 27).

31 R Lahti, ‘Life Imprisonment and Other Long-Term Sentences in the Finnish Criminal Justice System: Fluctuations in Penal Policy’ in Khalid Ghanayim and Yuval Shany (eds), The Quest for Core Values in the Application of Legal Norms. Essays in Honor of Mordechai Kremnitzer (Cham 2021) 215; M Tonry, ‘Predictions of Dangerousness in Sentencing’ in M Tonry (ed) American Sentencing What happens and why? Crime and Justice (vol. 48, University of Chicago Press 2019) 473.