ABSTRACT

This paper explores the transformation of community archaeology and heritage in a particular part of the UK with unique and somewhat conservative sets of structures for delivering public archaeology. The transformation is ongoing and is bounded by a range of theoretical, methodological and institutional constraints. These frameworks provide the context for an account of the successes and failures of projects in north-east Wales. Important strands of thought and action include the role of national identity in place-making and the ways in which national political priorities may need to inform and shape local initiatives. The paper discusses some of the theoretical and practical approaches that may be suited to further developing community archaeology and heritage in Wales and beyond.

Introduction

This paper tells the story of a transformative journey in which a long-established and slightly conservative organization has begun thinking and acting in new ways to deliver community archaeology and heritage programmes. Community archaeology is situated in several frameworks. Some of these concern the theory and practice of public archaeology in the round (Gould Citation2016; Matsuda Citation2016; Moshenska Citation2017; Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez Citation2015); others agonize over the meaning and role of ‘community’, ‘engagement’ and ‘heritage’ (Grima Citation2016; Matthews Citation2019; Trepal, Scarlett, and Lafreniere Citation2019); yet others are political, cultural and financial (González-Ruibal, González, and Criado-Boado Citation2019; Merriman Citation2004; Moshenska Citation2017; Stottman Citation2016; Watson Citation2007). This paper is primarily concerned with the last of these. This case study is important because of the nature of the organization, and the political and social considerations which impinge on its decision-making. Lessons have been learned, and continue to be learned, both inside and outside the organization. The purpose of this paper is not to say ‘we know best’, but rather to encourage others who may find themselves frustrated by frameworks not of their making and not always fit for purpose. We suggest that radical change need not require narcissistic disruption and the creation of brash new enterprises; instead, incremental change to an established archaeological ‘ecosystem’ can be more beneficial in the long run. The subject of this study is located in a particular set of circumstances – but we hope that the lessons we have learned are more widely applicable.

The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT) was established in 1975 as a charity, its object being ‘to educate the public in archaeology’. CPAT is one of four such Trusts in Wales, which carry out a wide range of functions in support of this object. From its earliest days CPAT was concerned with public engagement in the widest possible sense; however, this tended to be expressed through conventional didactic approaches with the Trusts’ archaeologists as experts, and the public as recipients of expertise. Although CPAT developed new audiences in the early 2000s, the style and method of delivery remained largely unchanged. Community engagement was often seen as an ‘add on’ to other projects whose main priorities were focussed on research or heritage management. Several factors have influenced the transformation to the present position, which is itself in flux, and we offer this account of our journey towards self-sustainability as very much a work in progress.

Structures and systems: archaeology and communities in Wales

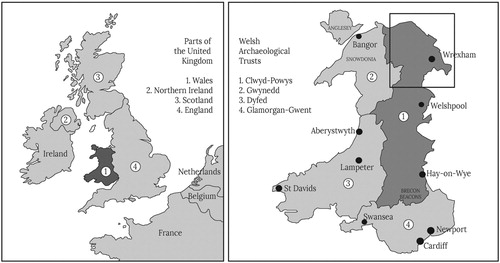

As archaeologists we recognize the importance of context, and so before describing our journey in detail it is important to understand the broader political and cultural context in which we operate in Wales (). Archaeology in the UK has been characterized as a series of complex and overlapping ‘ecosystems’ which together make up ‘biospheres’; these ‘biospheres’ are arranged differently in the four constituent nations of the UK (Belford Citation2020). England’s economic and cultural dominance in the unequal union means that arrangements there are often seen as synonymous with those in other parts of the UK. However, this is not the case for archaeology and cultural heritage. We begin with some wider political context: partly because of this journal’s international readership, but also because the coercions and compromises which have forged the UK resonate in the ways in which modern communities understand and engage with the historic environment.

Figure 1. Wales in context. Left: Wales (darker shaded) and surrounding countries, including the other constituent nations of the United Kingdom. Right: Wales showing the territories of the four Welsh Archaeological Trusts, with CPAT darker shaded. The box shows the location of . Drawing © Paul Belford.

Wales effectively lost its independence as a nation in 1282 with the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd; English kings then ruled it for 250 years, with indirect governance of the borderlands through territories called Marcher Lordships (Davies Citation1990). Wales was fully incorporated into the English legal system in the 1530s and 1540s: the Marcher Lordships were abolished, the modern border between England and Wales was defined, the internal administration of Wales was re-organized, and English was made the official language. Wales provided a prototype for English colonialism elsewhere in the British Isles. In Scotland, the accession of James VI to the English throne effectively created a ‘union of the crowns’ from 1603; formal union followed in 1706 and 1707 (Munck Citation2005). In Ireland, the bloody English conquest which had begun in the sixteenth century concluded with an Act of Union in 1801; this came to an end with the establishment of the Irish Free State in the 1920s, and the partition of Northern Ireland (Coleman Citation2013). The UK therefore is less than 100 years old but contains administrative bodies that are much older and which have often identified themselves in opposition to the others.

Irish and Scottish identities are well-developed and have strong international recognition; a result of the careful crafting of origin myths playing on real or perceived resistance to English hegemony, and the way that active diasporic populations promulgated them (Cooney Citation1996; Cooney Citation2001; James Citation2007; Meskell Citation2007). Wales, in contrast, has a less vocal international diaspora and – perhaps because of its earlier union with England – more muted nationalist aspirations (Champion Citation1996). Nevertheless, the growth of Welsh economic power during the industrial revolution, which led to greater self-confidence in the use of language and other expressions of identity gave impetus to such aspirations. What follows is a summary of the political background to the heritage context (for a full account of this see Belford Citation2018).

Agitation for devolution originated in the nineteenth century, but formal repatriation of political powers did not begin until the second part of the twentieth century. Early moves included the creation of a separate Welsh Office (1964), legal recognition of the Welsh language (1967), and an unsuccessful referendum on devolution in 1979 (Davies Citation1990; Evans Citation2006). This rebalancing was not benign magnanimity: it was the UK government’s pragmatic response to unease, and therefore entirely in keeping with its neo-/post-colonial approach to power relations elsewhere (Thomas Citation2013). Formal devolution followed the election of a UK Labour government in 1997.

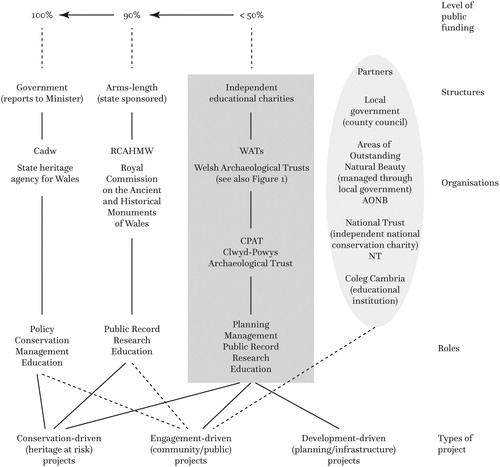

Meanwhile, historic environment functions had already become increasingly separately administered. Royal Commissions on ‘ancient and historical monuments’ for Wales, Scotland and England were created in 1908 to characterize the archaeological resource. Although nineteenth-century legislation had introduced ‘Inspectors’ of ancient monuments this was a very Anglo-centric function until well into the twentieth century. By the time ancient monuments responsibilities had been devolved to the Welsh Office in 1969, a distinctive ‘Welsh’ approach had emerged along with a Wales-based team of ancient monument Inspectors (Belford Citation2018). In 1984 Welsh Office historic environment functions were passed to Cadw – an agency with different degrees of separation at different (political) times – which combined regulatory, conservation and visitor management roles. Meanwhile, the mid-1970s saw the establishment of the four Welsh Archaeological Trusts (WATs). These independent educational charitable trusts carry out much of the day-to-day research and characterization that state heritage agencies undertake elsewhere. Since the incorporation of archaeology into planning legislation in the early 1990s, the WATs also undertake advisory functions which in other parts of the UK are undertaken by local authorities (Belford Citation2018, Citation2020). The relationships between the various actors are shown in .

Figure 2. Diagram showing the relationships between the different organizations, institutions and projects mentioned in the text. Drawing © Paul Belford.

This historic environment ‘tripod’ in Wales – Cadw, the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) and the WATs – provides a generally stable and well-co-ordinated framework within which archaeological services and experiences are delivered to the public (Belford Citation2018). The unique status of the WATs makes them central to the provision of both general public services as well as overtly ‘public’ programmes of archaeological engagement; their independent institutional status potentially provides greater flexibility. At the time of writing approximately 50% of CPAT’s income comes from various streams of public funding, with the remainder from commercial archaeological services and other fundraising. Public funding supports four main strands: planning services, the Historic Environment Record (HER), heritage management and ‘education and outreach’. All of these have some level of public engagement: planning services is concerned with managing the impact of development on archaeology and cultural heritage through the spatial planning system; their advice is supported through (and results fed back into) the HER – which uniquely in Wales is both freely publicly accessible online, and a statutory obligation for Welsh Government to maintain. The heritage management strand advises a wide range of landowners, groups and individuals.

Before 2013, the public archaeology strand at CPAT was regarded as a subset of ‘heritage management’ work; consequently its status and importance – both within the organization and the wider world – was understated. Change at CPAT began that year when one of the authors (Paul Belford) was appointed as the new Trust Director (Chief Executive); only the third post-holder in 40 years. Later that year a new ‘community archaeology’ post was created; initially the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) partly funded a placement that developed into a separate Community Archaeology post to which the other author (Penelope Foreman) was appointed in 2017. At the same time CPAT was able to access a new – albeit limited – stream of funding from Cadw for community archaeology projects in north-east Wales. This moment therefore provided an opportunity to create a new ‘Education and Outreach’ department with its own funding stream. Inevitably there were tensions between established approaches which prioritized research and heritage management, and new ones which foregrounded community-focussed practice.

At the same time, the political and social landscape within which CPAT operated had begun to change. Ultimately, the Welsh Government, a Labour-led administration flexing some of its newly-devolved law-making muscles in the teeth of a firmly austerity-driven Conservative UK administration, introduced two key pieces of legislation. These were the Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, in which a commitment was made to seven well-being goals (of which more below); and the Historic Environment (Wales) Act 2016, which sought to strengthen protection of historic environment assets and systems. Other relevant areas of Welsh policy divergence included spatial planning, health and social care.

North-east Wales: problems and opportunities

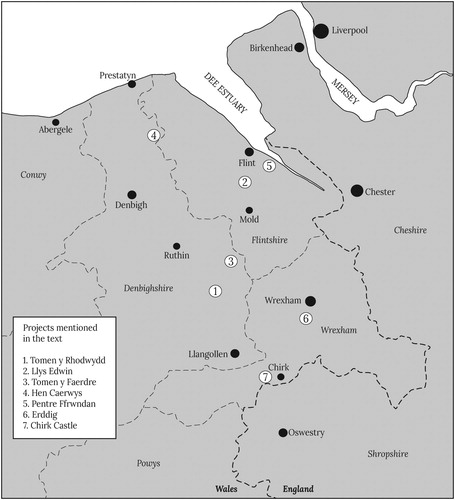

The term ‘north-east Wales’ is commonly used to describe the area covered by the three counties of Flintshire, Denbighshire and Wrexham (). Historically associated with industries such as coal mining, lead mining, pottery and brick manufacture, ironworking and engineering, communities in these areas have suffered from protracted industrial decline and the resulting economic and social issues. Industrial heritage is an important aspect of the region’s identity, but there is also pride in earlier strands of history: prehistoric, Roman and medieval. Despite some success in attracting or retaining high-tech industries – a notable example being the Airbus aerospace facility at Broughton (Flintshire) – the overwhelming impression of north-east Wales is one of economic poverty, social exclusion and deprivation (Save the Children Citation2012; Welsh Government Citation2019).

Figure 3. Map of north-east Wales showing administrative boundaries, principal settlements, and the locations of projects mentioned in the text. Drawing © Paul Belford.

The Welsh Government’s own statistics bear out this impression. A baseline study in 2012 identified 52 areas of extreme deprivation. Four of the 10 most deprived areas in Wales were in north-east Wales, where 34% of the population were in receipt of income-related benefits. Other indicators included overall income, geographical access to services, employment, community safety, health, physical environment, education, and housing (Welsh Government Citation2014). Parts of north-east Wales had some of the highest levels of educational deprivation in the country, as well as some of the highest levels of housing deprivation (including no central heating and living in overcrowded conditions). These are long-standing issues which pre-date formal devolution; however, the ongoing process of devolution has enabled Welsh Government to develop policies and programmes to tackle some of these issues.

Public funding is politically directed. As well as improving understanding and protection of the historic environment, programmes of archaeological work must also deliver social and economic outcomes (or at least attempt to do so). These policies have changed during the lifetime of the archaeological projects described here; consequently, the projects themselves have reflected these changes. The political context is important: the Welsh Assembly or Senedd has gained power and authority in the quarter-century of its existence. The Senedd contains 60 ‘Assembly Members’ (AMs) who since 2011 are elected for five-year terms. A devolution referendum that year approved the assembly’s ability to legislate in its devolved ‘areas of competence’ without approval from the UK Parliament at Westminster. The 2011 elections returned Labour AMs to 30 seats, establishing a Labour minority government. It was this administration which passed the legislation noted above. In the 2016 elections, 29 Labour AMs were elected and so the post-2016 government is a minority coalition between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. In practice the Welsh nationalist party, Plaid Cymru, is key to the balance of power: generally left-leaning but also sensitive on cultural heritage matters, their influence since 2016 has made a difference to policy affecting community archaeology.

The government of 2011–2016 adopted a robust approach to tackling poverty, social exclusion, health and well-being. Using the 2011 Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation, it identified ‘clusters’ of deprivation across Wales. The most deprived 10% were defined as ‘Communities First’ areas, and these became the priority for funding and support for a wide range of initiatives. Five of these were located in north-east Wales (Welsh Government and Ipsos MORI Citation2015; National Assembly for Wales Citation2001; National Assembly for Wales Citation2017). The government appointed ‘Communities First’ officers to deliver some of these outcomes, and applications for Welsh Government funding – including archaeology and cultural heritage – were strongly encouraged to target these areas. It was in this atmosphere that Cadw developed the ‘North-East Wales Community Archaeology’ (NEWCA) funding stream, to enable CPAT to lead on a range of conservation-led projects in the region. The same impulses in Welsh Government which had led to the ‘Communities First’ scheme subsequently resulted in the Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. This identified seven well-being goals intended to make Wales prosperous, resilient, healthier and more equal, and to produce a globally-responsible Wales of ‘cohesive communities’ and ‘vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language’.

The 2016 election results shifted the political balance in the Senedd to a minority Labour administration, and ultimately the ‘Communities First’ initiative was abandoned. Instead, the broader well-being goals were used to direct public funding more broadly. At the same time there was a change in ministerial portfolios. During 2011–2016 archaeology and cultural heritage had been the responsibility of the ambitious Labour AM Ken Skates, who had driven the creation of the Historic Environment (Wales) Act passed in 2016. After the elections, Skates was rewarded with the larger and higher-profile Economy and Transport portfolio. The portfolio for Culture, Tourism and Sport ultimately passed to the AM Dafydd Elis-Thomas, formerly of Plaid Cymru but independent since 2017. In 2018 Elis-Thomas set out his Priorities for the Historic Environment of Wales (Welsh Government Citation2018). The political use of the historic environment was therefore more neutrally position, although publicly funded archaeology and cultural heritage projects were still expected to address the seven well-being goals.

Community archaeology and conservation management

The remainder of this paper looks at some of the archaeological projects that CPAT has undertaken in north-east Wales and assesses their impact on people and places. The first section describes the series of small-scale projects which have taken place under the NEWCA programme of funding; the next section looks at other CPAT publicly-funded archaeology projects undertaken in north-east Wales. The two streams are interlinked: longer-term projects intended to assess heritage at risk have inspired some NEWCA projects, and in other cases work done as part of the NEWCA programme has generated separate spin-off projects (see ).

Initially at least the NEWCA programme was entirely funded by Cadw. As a result, sites were chosen that reflected the remit of that body: they had to be Scheduled (a state-designated heritage asset) and at risk of deterioration. Secondary considerations included opportunities for training and volunteer involvement, the range of local heritage interest groups, and the potential future legacy and public engagement. Consequently, sites were carefully chosen through discussion between Cadw and CPAT, requiring a negotiated balance between ambition and resources. Initially, the project focussed exclusively on medieval high-status sites, specifically motte-and-bailey castles (earthwork fortifications) and llys (princely courts). These are common site types in north-east Wales, but relatively under-studied, and a focus of both site-specific and synthetic CPAT projects at the time the NEWCA programme was established. Moreover they are iconic places in Welsh national identity. The NEWCA programme has evolved an approach in which each year has a primary project, with smaller efforts being made on other sites either to prepare work for the next season or to conclude previous efforts. We have taken care to ensure that the geographical and demographic spread is as even as possible; a key driver is ensuring a sustainable legacy.

The NEWCA programme has as much about conservation as conventional archaeological excavation. This combination of research and conservation – of both the natural and historic environments – captured a wide demographic of local volunteers and enabled cooperation from important partner organizations. From the outset, the NEWCA project worked closely with Coleg Cambria, a Further and Higher Education college with six campus sites across north-east Wales and over 7000 full-time and 20,000 part-time students. Coleg Cambria was created in 2013 from a merger of existing organizations, so the timing of the NEWCA project was ideal for developing partnerships with this new and dynamic institution. Another evolving partnership is with the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). An AONB is a landscape designation similar to a National Park, with less autonomy but the same weight in planning terms; all AONBs have a management plan and a management committee to ensure delivery of the AONB’s purpose of conserving and enhancing the designated landscape.

The primary focus of the 2014 season was at Tomen y Rhodwydd (Denbighshire) (). Owain ap Gruffydd ap Cynan (king of Gwynedd) constructed a short-lived motte-and-bailey castle in around 1150 as a statement of expanding power in Dyffryn Clwyd but it was taken and destroyed in 1157 (Pratt Citation1979). Tomen y Rhodwydd was identified as a priority for vegetation clearance, as dense gorse and hawthorn growth on the monument had encouraged significant populations of burrowing animals, damaging the earthworks. Vegetation clearance had practical and pedagogical objectives. The simplest was to improve the conservation of the monument by removing the vegetation; this of course enabled clear sight of the monument for surveying: the site had never been surveyed before and so a priority was to generate an accurate topographical plan. Clearance also made the monument more visible to the public, opening up a circular walk around the site for the first time, and so introducing opportunities for formal and informal learning and public engagement.

Figure 4. Conservation work at Tomen y Rhodwydd: clearing vegetation from the ramparts of the earthwork castle. Photo: CPAT 4122–0120 © CPAT.

Led by CPAT staff, volunteers from local heritage groups and students from Coleg Cambria formed working groups to undertake clearance and survey, enabling them to identify heritage management issues in addition to archaeological information. At the same time outreach in the form of school visits, talks, historical re-enactment and an open day engaged the local community. CPAT has a close working relationship with Cwmwd Ial, a medieval re-enactment society based in north-east Wales. This means that immersive and engaging activities with authentic settings are a regular and important feature of outreach activities. This is important for schools and family events where the re-enactors act as a ‘draw’ and gateway to learning opportunities about the archaeology on site (Grant, Belford, and Culshaw Citation2014). Work at Tomen y Rhodwydd continued in the same vein in 2015 and 2016, with some additional strands of activity (Grant Citation2015; Grant Citation2016; Grant Citation2017). Coleg Cambria students were trained in digital field survey on site, and a special AONB-funded Field Workshop Day School was run for students of Chester and Liverpool Universities. Archaeologists from CPAT also contributed to on-campus agricultural and land management courses at Coleg Cambria, a rare opportunity to engage with young people from the farming community.

Meanwhile in 2015 work began at Llys Edwin, Northop (Flintshire) – a medieval moated enclosure containing the remains of a series of fortified halls (). The name of the site provides an association with an Eadwine (or Edwin) of Tegeingl, an eleventh-century historical figure mentioned in the Domesday Book (Spurgeon Citation1981). T. A. Glenn excavated the site in 1931, identifying four phases of occupation in which successive timber structures were eventually replaced by a stone hall, probably in the 13th century (Silvester Citation2015). Work in 2015 was limited to a training session in digital survey for local volunteers and students from Glyndwr University. This formed the basis for a larger-scale survey of the entire site the following year. Working with students from both archaeology and ecology departments meant that conversations in the field illuminated both challenges and common ground between disciplines, providing a unique opportunity to explore these themes whilst on active fieldwork.

Figure 5. Excavation at Llys Edwin, with participants undertaking a wide range of archaeological activities. Photo: CPAT 4428–0090 © CPAT.

Work at Llys Edwin intensified in 2017 and 2018, when excavations were undertaken to explore the extent of the 1931 fieldwork and to more accurately record its location and the remains encountered. As well as this exercise in real-world archaeological historiography, this work explored the current condition of the site which was being impacted by vegetation growth and animal burrowing. Students and volunteers worked side by side on the excavation, uncovering masonry walls and a substantial assemblage of artefacts, meaning the subsequent open day gave ample opportunity for the public to examine objects from everyday life on site. In 2018, the project also featured a Glyndŵr University-organized finds-processing workshop closely involving local metal detectorists in an attempt to engage this sometimes hard-to-reach community (Grant Citation2018).

In 2019, the NEWCA programme returned to its roots by conducting vegetation clearance at Tomen y Faerdre (Denbighshire), another earthwork castle. CPAT had conducted a topographic survey the year before. Tomen y Faerdre is a substantial site, despite stone quarrying damage; volunteers joined CPAT and AONB staff to undertake vegetation clearance, to enable improved visibility and access. In the same year, CPAT delivered workshops in field practice and basic archaeological skills – one series for site volunteers at Chirk Castle, and one for adult learners with complex learning needs on the ‘Independent Life Skills’ stream at Coleg Cambria, both of which are detailed below. Though the character of these two sets of workshops was very different, necessitated by the very different pedagogical needs of the participants and diverging desired outcomes, archaeological skills and the social and well-being benefits of active participation were constant. Whilst the Chirk Castle volunteers required a speedy but solid introduction to fieldwork, safety, and communication skills for digging at a public-facing excavation site, the Coleg Cambria participants needed carefully tailored, hands on learning that afforded the delivery of key life skills within a framework of archaeological learning. Feedback from both sessions was overwhelmingly positive.

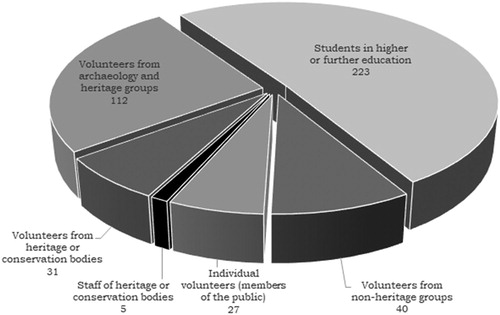

The small scale of the individual projects under the NEWCA programme creates risk around sustainability and long-term legacy. However, the programme as a whole has enormous strengths. Hundreds of volunteers of all ages and backgrounds have taken part during the first five years (). There is a constant and sustained level of interest from across the local communities, and in the longer term, the project has maintained a high degree of participation and support. The key lesson from the NEWCA programme is not so much volume but consistency. Over five years the project has cost less than £25,000 – yet it has achieved so much more lasting impact than a one-off project of the same value. Important lessons have been learned for training and development, not least ensuring structured learning for individuals. One of the frustrations has been the ‘top-down’ nature of the project necessitated by Cadw funding and control; it would have been more rewarding to engage local communities in the decision-making around which sites to research, survey and conserve. The NEWCA projects have gone on to inspire other projects in north-east Wales, and these are discussed in the next section.

Public archaeology as community archaeology

The NEWCA programme complements other community-focussed projects that CPAT has undertaken in north-east Wales. These have had mixed success in generating sustainable community outcomes, and they have produced considerable debate about how to measure these outcomes. One example which pre-dated the NEWCA programme took place at Hen Caerwys (Flintshire). Hidden in dense woodland, the complex series of stone structures that comprise Hen Caerwys were only ‘discovered’ by an amateur historian in the 1960s and interpreted as an abandoned nucleated medieval settlement, the only one in north-east Wales (Silvester Citation2006). This interpretation went uncontested until the CPAT project which ran from 2011 to 2015. The project represented the first systematic look at these remains, which turned out to be a more complex palimpsest of prehistoric, medieval and later structures and features (Silvester and Davies Citation2011; Silvester and Davies Citation2012; Silvester et al. Citation2014). The relatively small scale of fieldwork at Hen Caerwys meant that the origins and development of the settlement remained unresolved. Arguably therefore the Hen Caerwys project failed to meet some of its research objectives. Moreover, it did not fully develop the potential for community engagement. It was a classic ‘top-down’ community project that was primarily archaeological research and resource management issues-driven. Nevertheless, the project succeeded in generating local volunteer interest and developing links with interested groups and with universities.

Many of the same groups and individuals who had engaged with the Hen Caerwys project also came to be involved in the various strands of the NEWCA project, and with other projects in north-east Wales. One of these was at Pentre Ffwrndan, Oakenholt (Flintshire), one of a series of small settlements along the south edge of the Dee estuary. Chester Road, until the 1980s, the main road along the north Wales coast, strings these settlements together; this road, and the river access, meant that this part of Flintshire had prospered in the nineteenth century as a communication and trading route serving the industries of north-east Wales. Pentre Ffrwndan had seen significant activity in the Roman period for the same geographical reasons: the modern road follows much the same line as its Roman predecessor, which linked the legionary base at Deva (Chester) with the principal fort in north Wales at Segontium (Caernarfon) (Burnham and Davies Citation2010; Jones Citation2017). Roman industry and settlement along the Deeside strip had been investigated archaeologically since the nineteenth century; CPAT and others had undertaken significant work from the 1980s, and substantial remains were encountered during development projects (Petch and Taylor Citation1925; Petch Citation1936; O'Leary, Blockley, and Musson Citation1989; Dodd Citation2013; Dodd Citation2016). The local community had taken a particular interest in rescue excavations at Pentre Ffrwndan in 2013, which revealed the well-preserved remains of the Roman road and roadside settlement. CPAT built on that interest to deliver a multi-faceted community project here in 2017 and 2018 (Grant and Sperr Citation2017; Jones, Foreman, and Grant Citation2019).

The area was adjacent to two of the former ‘Communities First’ cluster areas, and participants were drawn from these areas as well as the immediate community. CPAT wanted to deliver a public-facing programme of activities to boost local engagement with heritage by bringing people together for a shared experience in exploring the archaeology and spend time doing creative and collaborative activities outside – all key features of successful small-scale community well-being projects (O’Donoghue Citation2019). Volunteers were recruited through social media, the CPAT network of ‘Friends’, local leafleting and local radio. Both seasons of work provided similar opportunities: an excavation, an ‘ask the expert’ drop-in, and a series of activity open days for schools and families with crafts, cooking and other re-enactments (). Archaeologically, the results were spectacular: as well as the remains of the Roman road, a complex high-status multi-phase Roman building was revealed, along with evidence for industrial activity (in this case lead smelting). This gave volunteers experience in deciphering more complex stratigraphy, and an area of earlier disturbance provided fertile ground for sieving by visiting schools under close supervision from CPAT staff and University of Chester students.

Figure 7. Typical morning scene at Pentre Ffrwndan. Excavation in progress, with visitors at the ‘ask the expert’ drop-in tents and re-enactors’ displays. Photo: CPAT 4564–0032 © CPAT.

Volunteer engagement was generally very positive, but surprisingly an opportunity for local residents to excavate archaeological test pits in their own gardens and on community land attracted little interest. Despite extensive consultation including the provision of information packs and a training session, in the event no households took part and no test pits were opened. Reasons given for this reluctance included the weather and a fear of making a mess; but the concerns were either that the participants themselves would do damage to the archaeology – or conversely that the archaeology would prove to be so spectacular that they would be overwhelmed. On reflection, it seems likely that the preparatory work did not go far enough. It was difficult for people to relate actions to outcomes, and so the high level of public curiosity did not translate to an activity that on the face of it seemed highly attractive. The more moderated relationship to archaeology delivered through the drop-in sessions proved more popular. Overall across both seasons (a total of less than three weeks in the field), over 350 people actively participated in the archaeological project.

In 2018 work began on another project in the region, which was to supersede the Pentre Ffrwndan project the following year. This was developed jointly with the National Trust, and looked at medieval and later sites on their properties at Chirk and Erddig: both stately homes with landscaped gardens, but both in close proximity to the former coal mining and steelmaking town of Wrexham. Again the archaeological results proved to be extremely interesting, including work on the iconic medieval earthwork of Offa’s Dyke – built in the eighth century and running for over 120km through the borderlands between England and Wales. More prosaic targets – a garden wall and part of an eighteenth-century workshop – were just as attractive to the more than 500 volunteers, students and other participants (Grant and Jones Citation2019a; Grant and Jones Citation2019b) (). The role of the National Trust, as a joint funder but also as host and facilitator of logistics – including their substantial numbers of volunteers – made a substantial difference; the fact that both sites are existing visitor attractions with the necessary infrastructure immensely improved the offer for local communities.

Figure 8. Volunteers working on medieval and later landscape features at Chirk, with the castle in the background. Photo: CPAT 4565–0050 © CPAT.

In their different ways, these projects have tried to move beyond didactic approaches and conventional (generally white, middle-class, retired) demographics to engage new audiences with archaeology and cultural heritage in its broadest sense. This has been a gradual process, partly due to institutional and structural conservatism within the sector (including our own organization), but also due to the different needs and contexts of the various communities. One of the biggest frustrations has been the need to spread extremely limited public funding very widely; consequently, projects are either of short duration, of limited scope, or both. We have tried very hard to develop continuity and progression for individuals and community, but the sporadic and insecure nature of much of the funding has made this difficult to achieve consistently.

Doing things better – moving beyond archaeology

The evolution of the public archaeology ‘offer’ from CPAT to the communities it serves has changed during the last five years. To some extent, the direction of travel has been influenced by changes in government policy and strategy, which have created the frameworks within which funding is sought and outcomes delivered. However, CPAT is an independent entity, and has always remained determined to deliver both high-quality archaeology and a high level of community engagement. Generally there are three tiers of engagement which only very loosely correspond to established ideas of ‘citizen participation’ (Belford Citation2011, Citation2014). Some participants are highly skilled and are actively involved in non-intrusive survey and excavation and site recording. A much larger number are involved in ‘digging’ in more general terms, and to some extent post-excavation processing; generally these participants tend to eschew tasks involving mathematics, drawing and writing. Then there is a large number of observers – some of whom may try re-enactor-presented activities – but who are generally happy to be receivers of information rather than creators of the archaeological data.

As these projects have developed, they have moved beyond ‘traditional’ outreach and become – originally by happy accident and later by design – a collective of outcomes that transcends the purely archaeological into education, well-being, and community cohesion. As well as on the established health benefits of undertaking collective tasks outdoors in older volunteers (Husk, Lovell, and Garside Citation2018) and on the employability, confidence, and positive community engagement of higher education students (Munge, Thomas, and Heck Citation2017), there is a growing body of work on the specific impacts of archaeology and heritage on key well-being indicators (Sayer Citation2015; Pennington et al. Citation2019; Shimko Citation2019). As discussed earlier, CPAT is an organization receiving public funding from the Welsh Government, so we have an obligation to align our activities with the Well Being of Future Generations Act. It is only really possible to meaningfully achieve this through partnership working – and our close and long-standing relationships with key public bodies and organizations in north-east Wales (such as local authorities, the AONB and Cadw) are essential. Such relationships take time to build up, and rely on the characters of individuals to maintain. This is why we argue that incremental change to an established organization such as CPAT is more sustainable than new short-term initiatives which don’t have the same institutional drive to create legacy.

This is encapsulated by the way in which recent iterations of NEWCA have gone beyond the laudable aims of clearing neglected sites and raising local awareness of the cultural and historic setting of their landscape, and embraced ways of enabling volunteer participants to be exposed to new skills, networks, and experiences. The most measurable of these non-archaeological outcomes is the impact upon participants from the ‘Independent Living Skills’ (ILS) students at Coleg Cambria’s Northop campus. The ILS department approached CPAT with a view to enhancing and improving the ‘Life Skills’ of students with short classroom-based sessions paired with site visits to Llys Edwin, which is adjacent to the Northop campus (Grant Citation2019). The World Health Organization (WHO) has included decision-making, problem solving, creative and critical thinking, communication, self-awareness, empathy, assertiveness, and resilience among these ‘Life Skills’ (WHO Citation1999). In 2019, 85 students took part in sessions specifically tailored to their learning level and educational needs. We kept formal learning (presentations and handouts) to a minimum; instead the focus was on hands-on tasks involving finds processing, cleaning and cataloguing. The model was successful with positive feedback from both students and staff from the college, and as a result, a framework was developed for future versions of these workshops to become part of a long-term strategy for archaeology as part of the ILS department ().

These aims and methods are aspirational in their design – towards a model of community archaeology that embodies what our adjacent discipline, museum studies, calls ‘socially engaged practice’: that is, one which enables genuine community co-creation, shares authority over interpretation and debate, and works actively towards tackling social issues relevant to the communities it engages (Sandell and Nightingale Citation2012). Whilst the idea of archaeology as a social discipline that is fundamentally entwined with myriad human rights issues is nothing new, archaeologists have sometimes been slow to adopt practices which actively embrace this potential, frequently maintaining an over-academic and exclusionary approach to community archaeology that prevents it from becoming truly socially engaged practice (Darvill Citation1995; Hardy Citation2017; Moshenska Citation2018). Several projects that have achieved a degree of public awareness and engagement, largely involving veterans and addressing both their mental and physical well-being, have addressed this issue (Evans et al. Citation2019; Everill, Bennett, and Burnell Citation2020). Much of the recent work in this area has been focused upon mental health, and has examined outcomes based upon this; there has been less practice of genuinely socially engaged practice around empowering and engaging socio-economically deprived communities through co-created, democratized project development.

However, measuring the effectiveness of community projects is very hard. It is relatively easy to measure numbers – indeed public funding requires measuring numbers – but quantitative data only tells part of the story. Measuring impact requires qualitative data. Yet although we have made a significant shift in our thinking at CPAT, the wider profession still tends to see community archaeology and heritage as marginal. In many cases ‘public archaeology is regrettably treated as a luxury … detailed monitoring and evaluation would be luxury upon a luxury’ (Moshenska Citation2017). Yet community archaeology is not a luxury: public interest in our work, public attitude to the discipline, the willingness of future generations to train as archaeologists, the willingness of future legislature and funding bodies to support us all hinge on the way we engage with those beyond the bubble of our discipline. We believe that to understand how we are managing to do this requires that the evaluation of our entire process – from the initial project design all the way through to the final report – to be built into any and all projects at their inception.

Though the projects described here have largely been monitored in the usual quantitative way, informal feedback and observations formed vital qualitative data that adds the ‘story’ – that human element providing evidence for impact. This has provoked CPAT into developing a more reflexive practice for our work in north-east Wales. Previously, the criteria for ‘success’ was almost exclusively a numbers game, where raw figures of participants or visitors were the yardstick of outreach efficacy. Public archaeology has been critiqued for a lack of rigour and transparency when it comes to evaluation, a deficiency that enables a lack of reflection and refinement of practice (Ellenberger and Richardson Citation2019). With a more critical approach to community archaeology, reframing it as an opportunity for using archaeology as a powerful tool for social, economic, health and well-being impacts, CPAT as an organization has begun to redefine ‘value’ and reposition itself within the communities it works within. Fundamentally, CPAT and the other WATs are charities with the mission of ‘educating the public in archaeology’ – and using this as a launchpad for conversations, strategies, and actions on the nature of current and future community-based projects has resulted in a shift towards more radical and agile practice which listens to, learns from, and works with the community itself.

The changes to the Pentre Ffrwndan project to reflect the reluctance of people there to undertake self-directed fieldwork is a case in point. Similar reactions have been noted elsewhere – for example on public archaeology projects with very different communities, where the need for ‘authorization’ has meant participants preferring a more ‘top-down’ approach (Belford Citation2011). From this, CPAT has begun designing community archaeology and heritage programmes that strike a delicate balance between direction from archaeologists and community co-creation.

Conclusions

It is clear from the many years of community archaeology in north-east Wales that success lies in an approach that embraces local networks, is open to partnership working, and is willing to embrace change. Developing close ties with the AONB has been fruitful in connecting the projects with a new collective of volunteers, and enabling some of the neglected sites to be cleared and made accessible in ways that would otherwise not have been possible. Motte and llys sites in north-east Wales are slowly becoming a bigger part of the ‘place’ to locals – the tapestry of the area’s history and heritage growing ever richer.

Whilst the NEWCA and Pentre Ffwrndan projects saw good volunteer numbers as a result of this willingness to work in partnership with other disciplines, the traditional nature of the outreach has not always helped to promote archaeology to a wider demographic – and has not safeguarded it even to the existing groups with a vested interest. In September 2019, the St Asaph Archaeology Society – a source of volunteers across several seasons – announced that it would cease to exist. The demographics of volunteering in north-east Wales, in common with much of the UK and the western world, are such that once-vibrant local groups like these are vulnerable (Thomas Citation2010). Part of the future of community archaeology must include ensuring that these types of groups can evolve: local interest must be maintained and professional support should ensure that they have the resources, skills, and experience to work on projects and research in their area, for the benefit of current and future volunteer archaeologists and their communities.

Impact is perhaps a useful concept here. Whilst individual well-being impacts are increasingly captured through standardized methods such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), or the UCL Museums Wellbeing Measures Toolkit, there is no parallel standardized or data-driven methodology to evaluate broader community and indeed wider public impact (Thomson and Chatterjee Citation2013; Warwick University Citation2019). This is despite growing calls from funding bodies, embodied in legislation such as the Well Being of Future Generations Act in Wales, to measure exactly this kind of impact as a yardstick for the social and economic value of archaeology to the public (Ellenberger and Richardson Citation2019). Therefore CPAT has begun to develop some mechanisms to try and collect more meaningful data, which are being trialled through these projects in north-east Wales. We have been collecting detailed (anonymized) demographic data to try and work out how our practices favour some groups over others. We are monitoring well-being for participants on long-term projects, using a survey method based on WEMWEB, which we are benchmarking against national and international standards. Fieldwork volunteers can opt in to a detailed ‘Volunteer Skills Handbook’ that is linked to the Archaeological Skills Passport and gives an opportunity for reflective practice, a portfolio of work to be collected, and several ways to feed back on their experience to CPAT staff during their time as a volunteer.

Although we are still in the early stages of testing, we are optimistic that the evaluation models which are emerging will give both quantitative and qualitative insight into the individual impact of participation. We are also aware that a large part of the potential constituency in the CPAT region does not engage at all with archaeology and heritage. We have therefore designed a ‘Community Heritage Survey’, to identify peoples’ ideas about, aspirations for, and challenges in accessing archaeology. The survey is designed to provide both empirical data, and a snapshot of community opinion, that will enable future community-centred outreach projects to succeed.

Two crucial points emerge from our work in north-east Wales. The first is that change is essential. For CPAT to deliver its charitable objective in the twenty-first century it is necessary to move beyond conventional ‘outreach’ and embrace new ways of working. Archaeology has a unique potential to deliver opportunities to develop an extraordinary range of transferable skills, to draw communities together in establishing meaningful links to pasts and place, and to affect physical and mental wellbeing through fieldwork and collaborative projects. This potential can only be tapped if archaeologists embrace challenges: using creative arts to express archaeological findings, accepting that diverse publics have agency as co-creators and co-curators of knowledge and interpretation, acknowledging the centrality of outreach as an integral and vital aspect of the discipline. This also means opening up of institutions that currently seem closed to large sections of the public. This leads to the second point. Ironically it is the longevity and security of the WATs that mean that they are best-placed to deliver a lot of this change. They curate all the archaeological data for Wales, manage it in day-to-day terms, and are experienced in delivering public benefit through community archaeology. Moreover, the WATs are rooted in their local places and communities, and at the same time act as a conduit between the aspirations of people on the ground and AMs in the Senedd. We still have a long way to go, but our transformative journey has begun.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our current and former colleagues at CPAT for enabling these projects to take place, in particular Ian Grant who has taken the lead on the NEWCA programme. Fieldwork was also supported by Nigel Jones (who developed the idea for the Pentre Ffrwndan project), Sophie Watson, Katie Longley, and Will Logan. Many thanks also to Viviana Culshaw, Alex Sperr, Chris Matthews and Mark Walters. We are also very grateful to Will Davies and Fiona Grant (Cadw), Kathy Laws (National Trust) and Howard Sutcliffe (Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB Officer at Denbighshire County Council). Of course our wonderful volunteers and project participants have made all the difference. We would also like to thank Abi McCullough and Ian Grant, as well as the anonymous reviewers, for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Notes on contributors

Dr Paul Belford, FSA MCIfA is the Director (CEO) of the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust. He is an archaeologist with diverse interests in late prehistoric, early medieval and post medieval archaeology; heritage policy and practice; and public engagement with the historic environment. Dr Belford also serves as a Trustee of the Black Country Living Museum (one of the UK's leading independent industrial museums), Size of Wales (an environmental charity) and as a Board Member of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (the association for cultural heritage professionals). He is also a Visiting Lecturer at the University of Chester.

Dr Penelope Foreman, PCIfA is the ‘Chief Storyteller and Memory Maker’ (aka Community Archaeologist) at the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust. Her archaeological areas of interest are Neolithic art and monuments; industrial and post-industrial urban sites; decolonization and diversity in archaeology; and community based heritage practice. Dr Foreman is on the committee of both the Equality and Diversity and Voluntary and Community Archaeology groups of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, and is a Trustee of Celf o Gwmpas, an ‘arts in health’ organization in Powys.

References

- Belford, Paul. 2011. “Archaeology, Community and Identity in an English New Town.” The Historic Environment: Policy and Practice 2 (1): 49–67. doi: 10.1179/175675011X12943261434602

- Belford, Paul. 2014. “Sustainability in Community Archaeology.” AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology 4 (2): 21–44.

- Belford, Paul. 2018. “Politics and Heritage: Developments in Historic Environment Policy and Practice in Wales.” The Historic Environment: Policy and Practice 9 (2): 1–25. doi: 10.1080/17567505.2018.1456721

- Belford, Paul. 2020. “Borderlands: Rethinking Archaeological Research Frameworks.” The Historic Environment: Policy and Practice 2–3. doi:10.1080/17567505.2020.1737777.

- Burnham, Barry C., and Jeffrey L. Davies. 2010. Roman Frontiers in Wales and the Marches. Aberystwyth: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales.

- Champion, Timothy. 1996. “Three Nations or One? Britain and the National Use of the Past.” In Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe, edited by M. Díaz-Andreu and T. Champion, 119–145. London: Routledge.

- Coleman, Marie. 2013. The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923. London: Routledge.

- Cooney, Gabriel. 1996. “Building the Future on the Past: Archaeology and the Construction of National Identity in Ireland.” In Nationalism and Archaeology in Europe, edited by M. Díaz-Andreu and T. Chamption, 146–163. London: Routledge.

- Cooney, Gabriel. 2001. “Bringing Contemporary Baggage to Neolithic Landscapes.” In Contested Landscapes: Movement, Exile and Place, edited by B. Bender and M. Wine, 165–180. Oxford: Berry.

- Darvill, Timothy. 1995. “Value Systems in Archaeology.” In Managing Archaeology, edited by M. A. Cooper, A. Firth, J. Carman, and D. Wheatley, 40–50. London: Routledge.

- Davies, John. 1990. A History of Wales. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Dodd, Lorna J. 2013. Residential Development at Croes Atti, Oakenholt, Flint. Unpublished Report. Earthworks Archaeology E1240.

- Dodd, Lorna J. 2016. Residential Development at Croes Atti, Oakenholt, Flint: An Archaeological Strip, Map and Map Excavation. Unpublished Report. Earthworks Archaeology E1242.

- Ellenberger, Kate, and Lorna-Jane Richardson. 2019. “Reflecting on Evaluation in Public Archaeology.” AP: Online Journal of Public Archaeology 8 (1): 65–94.

- Evans, John G. 2006. Devolution in Wales: Claims and Responses, 1937-1979. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Evans, Mark, Stuart Eve, Tony Pollard, and David Ulke. 2019. “Waterloo Uncovered: From Discoveries in Conflict Archaeology to Military Veteran Collaboration and Recovery on One of the World’s Most Famous Battlefields.” In Historic Landscapes and Mental Well-Being, edited by T. Darvill, K. Barrass, L. Drysdale, V. Heaslip, and Y. Staelens, 253–265. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Everill, Paul, Richard Bennett, and Karen Burnell. 2020. “Dig in: Archaeology as a Vehicle for Improved Wellbeing, and the Recovery/Rehabilitation of Military Personnel and Veterans.” Antiquity 94 (373): 212–277. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2019.85

- González-Ruibal, Alfredo, Pablo Alonso González, and Felipe Criado-Boado. 2019. “Against Reactionary Populism: Towards a New Public Archaeology.” Antiquity 92 (362): 507–515. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2017.227

- Gould, Peter G. 2016. “On the Case: Method in Public and Community Archaeology.” Public Archaeology 15 (1): 5–22. doi: 10.1080/14655187.2016.1199942

- Grant, Ian. 2015. North East Wales Community Archaeology Programme 2014-15. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1335.

- Grant, Ian. 2016. North-East Wales Community Archaeology Programme 2015-16. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1406.

- Grant, Ian. 2017. North-East Wales Community Archaeology Programme 2016-17. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1496.

- Grant, Ian. 2018. North-east Wales Community Archaeology Programme 2017-18. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1574.

- Grant, Ian. 2019. North-east Wales Community Archaeology Programme 2018-19. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1650.

- Grant, Ian, Paul Belford, and Viviana Culshaw. 2014. Tomen y Rhodwydd, De018, Denbighshire. Survey and Conservation 2014: North East Wales Community Archaeology. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report 1261.

- Grant, Ian, and Nigel W. Jones. 2019a. Wat’s Dyke, Erddig, Wrexham: Community Excavation. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1600.

- Grant, Ian, and Nigel W. Jones. 2019b. Chirk Castle, Wrexham: Community Excavation. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1631.

- Grant, Ian, and Alex Sperr. 2017. Pentre Ffwrndan Roman Settlement, Flintshire: Community Excavation and Outreach 2017-18. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No 1552.

- Grima, Reuben. 2016. “But Isn't All Archaeology ‘Public’ Archaeology?” Public Archaeology 15 (1): 50–58. doi: 10.1080/14655187.2016.1200350

- Hardy, Samuel. 2017. “The Archaeological Profession and Human Rights.” In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology, edited by G. Moshenska, 93–106. London: UCL Press.

- Husk, Kerryn, Rebecca Lovell, and Ruth Garside. 2018. “Prescribing Gardening and Conservation Activities for Health and Wellbeing in Older People.” Maturitas 110: A1–A2. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.12.013

- James, Sian. 2007. “Discourses of Identity in the Interpretation of the Past.” In The Archaeology of Identities: A Reader, edited by T. Insoll, 44–58. London: Routledge.

- Jones, Nyle W. 2017. Roman Deeside, Flintshire: Archaeological Assessment. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1470.

- Jones, Nyle W., Peter Foreman, and Ian Grant. 2019. Pentre Ffwrndan Roman Settlement, Flintshire: Community Excavation and Outreach 2018-19. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1633.

- Matsuda, Akira. 2016. “A Consideration of Public Archaeology Theories.” Public Archaeology 15 (1): 40–49. doi: 10.1080/14655187.2016.1209377

- Matthews, Christopher N. 2019. “Assemblages, Routines, and Social Justice Research in Community Archaeology.” Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 6 (3): 220–226. doi: 10.1080/20518196.2019.1600234

- Merriman, Nick. 2004. Public Archaeology. London: Routledge.

- Meskell, Lynn. 2007. “Archaeologies of Identity.” In The Archaeology of Identities: A Reader, edited by T. Insoll, 19–43. London: Routledge.

- Moshenska, Gabriel. 2017. “Introduction: Public Archaeology as Practice and Scholarship Where Archaeology Meets the World.” In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology, edited by G. Moshenska, 1–13. London: UCL Press.

- Moshenska, Gabriel. 2018. “Epilogue: Some Reflections on Community Archaeology and Heritage.” In Shared Knowledge, Shared Power: Engaging Local and Indigenous Heritage, edited by V. Apaydin, 143–146. New York: Springer.

- Munck, Thomas. 2005. Seventeenth-Century Europe: State, Conflict and Social Order in Europe 1598-1700. London: Palgrave.

- Munge, Brendon, Glyn Thomas, and Deborah Heck. 2017. “Outdoor Fieldwork in Higher Education: Learning From Multidisciplinary Experience.” Journal of Experiential Education 41 (1): 39–53. doi: 10.1177/1053825917742165

- National Assembly for Wales. 2001. Communities First Guidance. Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales. Accessed 1 July 2020. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/technologymls/english/resources/pdf/comfirst-e.pdf.

- National Assembly for Wales. 2017. Communities First Lessons Learnt. Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://senedd.wales/laid%20documents/cr-ld11141/cr-ld11141-e.pdf.

- O'Leary, Thomas J., Kevin Blockley, and Chris Musson. 1989. Pentre Farm, Flint. 1976-81. An Official Building in the Roman Lead Mining District. BAR British Series 207. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- O’Donoghue, Donal J. 2019. “High Value, Short Intervention Historic Landscape Projects: Practical Considerations for Voluntary Mental-Health Providers.” In Historic Landscapes and Mental Well-Being, edited by T. Darvill, K. Barrass, L. Drysdale, V. Heaslip, and Y. Staelens, 97–122. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Pennington, A., R. Jones, A. Bagnall, J. South, and R. Corcoran. 2019. Heritage and Wellbeing: The Impact of Historic Places and Assets on Community Wellbeing – A Scoping Review. London: What Works Centre for Wellbeing. Accessed 20 October 2019. https://whatworkswellbeing.org/product/heritage-and-wellbeing-full-scoping-review/.

- Petch, J. A. 1936. “Excavations at Pentre Ffwrndan, Near Flint in 1932, 1933 and 1934.” Archaeologia Cambrensis 91 (1): 74–92.

- Petch, J. A., and M. V. Taylor. 1925. “Report on the Excavations Carried out at Pentre, Flint During September 1924.” Flintshire Historical Society Publications 10 (2): 5–29.

- Pratt, David. 1979. “Tomen y Rhodwydd.” Archaeologia Cambrensis 127: 130–132.

- Richardson, Lorna-Jane, and Jaime Almansa-Sánchez. 2015. “Do you Even Know What Public Archaeology is? Trends, Theory, Practice, Ethics.” World Archaeology 47 (2): 194–211. doi: 10.1080/00438243.2015.1017599

- Sandell, Richard, and Eithne Nightingale. 2012. Museums, Equality and Social Justice. London: Routledge.

- Save the Children. 2012. Child Poverty Snapshots: The Local Picture in Wales. Cardiff: Save the Children. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/content/dam/global/reports/hunger-and-livelihoods/Child-Poverty-Snapshots-English.pdf.

- Sayer, Faye. 2015. “Can Digging Make you Happy? Archaeological Excavations, Happiness and Heritage.” Arts & Health 7 (3): 247–260. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2015.1060615

- Shimko, Hannah. 2019. Inspiring Creativity, Heritage & The Creative Industries: A Heritage Alliance Report. London: The Heritage Alliance. Accessed 20 October 2019. https://www.theheritagealliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/InspiringCreativity_THAreport.pdf.

- Silvester, Robert J. 2006. “Deserted Rural Settlements in Central and North-East Wales.” In Lost Farmsteads: Deserted Rural Settlements in Wales. CBA Research Report 148, edited by K. Roberts, 13–40. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Silvester, Robert J. 2015. The Llys and the Maerdref in East Wales. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report 1331.

- Silvester, Robert J., and Will Davies. 2011. Hen Caerwys Community Excavation, Caerwys, Flintshire. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1106.

- Silvester, Robert J., and Will Davies. 2012. Hen Caerwys Community Excavation, Caerwys, Flintshire. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1164.

- Silvester, Robert J., Will Davies, Caroline Pudney, and Paul Belford. 2014. Hen Caerwys Community Excavation, Caerwys, Flintshire: The Fourth Season. Unpublished Report. CPAT Report No. 1290.

- Spurgeon, C. J. 1981. “Moated Sites in Wales.” In Medieval Moated Sites in North-West Europe. BAR International Series 121, edited by F. A. Aberg and A. E. Brown, 19–70. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Stottman, M. J. 2016. “From the Bottom Up: Transforming Communities with Public Archaeology.” In Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects, edited by A. Atalay, L. R. Clauss, R. H. McGuire, and J. R. Welch, 179–196. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, Suzie. 2010. Community Archaeology in the UK: Recent Findings. York: Council for British Archaeology. Accessed 23 June 2020. https://new.archaeologyuk.org/Content/downloads/4911_CBA%20Community%20Report%202010.pdf.

- Thomas, Wyn. 2013. Hands off Wales: Nationhood and Militancy. Llandysul: Gomer Press.

- Thomson, Linda J., and Helen J. Chatterjee. 2013. UCL Museums Wellbeing Measures Toolkit. London: UCL. Accessed 20 October 2019. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture/sites/culture/files/ucl_museum_wellbeing_measures_toolkit_sept2013.pdf.

- Trepal, Dan, Sarah Fayen Scarlett, and Don Lafreniere. 2019. “Heritage Making Through Community Archaeology and the Spatial Humanities.” Journal of Community Archaeology and Heritage 6 (4): 238–256. doi: 10.1080/20518196.2019.1653516

- Warwick University. 2019. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales – WEMWBS. Warwick: Warwick University. Accessed 20 October 2019. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/.

- Watson, Sheila. 2007. Museums and Their Communities. Oxford: Routledge.

- Welsh Government. 2014. Communities First: 2012 Baseline. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Accessed 10 October 2019. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2018-12/151117-communities-first-2012-baseline-revised-en.pdf.

- Welsh Government. 2018. Priorities for the Historic Environment. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. 2019. Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2019 Results Report. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2020-06/welsh-index-multiple-deprivation-2019-results-report.pdf.

- Welsh Government and Ipsos MORI. 2015. Communities First: A Process Evaluation. Cardiff: Welsh Government. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2018-12/150226-communities-first-process-evaluation-en.pdf.

- WHO (World Health Organisation). 1999. Partners in Life Skills Education: Conclusions From a United Nations Inter-Agency Meeting. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Accessed 21 October 2019. https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/30.pdf.